Dickensians! discussion

This topic is about

Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit - Group Read 2

>

Little Dorrit II: Chapters 23 - 34

I cried buckets, both because she came to him when he needed her so badly, and because Arthur believes it is too late. Also, John made me cry. Arthur feels it too late for him to love Amy, and John knows she will never love him.

I cried buckets, both because she came to him when he needed her so badly, and because Arthur believes it is too late. Also, John made me cry. Arthur feels it too late for him to love Amy, and John knows she will never love him. I love your analysis, Jean. I also thought of Martha down at the river, and when reading about John, I had thoughts of Sidney Carton and his self-sacrifice. How amazing that Dickens understands every single human emotion.

Anne - I am also hopeful.

Clennam "watching out the night" reminded me of the night Amy and Maggie spent outside at their "party". Being awake at night can mean frivolity and company but being alone and friendless makes it a torment.

Clennam "watching out the night" reminded me of the night Amy and Maggie spent outside at their "party". Being awake at night can mean frivolity and company but being alone and friendless makes it a torment. It's annoying that some of Dickens' characters are so self-sacrificing! Arthur is being so noble about sending Amy away when neither of them really wants that.

I kind of get Arthur's self-sacrifice, Robin. How does he declare his love for Amy and ask to marry her now, when he is in prison, when he failed to recognize his love for her before and never asked to marry her then. If she were still poor, I don't think he would hesitate, but it has the appearance of wanting her more because of her position, and he could not bear people thinking that.

I kind of get Arthur's self-sacrifice, Robin. How does he declare his love for Amy and ask to marry her now, when he is in prison, when he failed to recognize his love for her before and never asked to marry her then. If she were still poor, I don't think he would hesitate, but it has the appearance of wanting her more because of her position, and he could not bear people thinking that. It seems very significant to me that he cannot forbid her to come at all...he just asks her not to come often. If his fortunes reverse, she will be waiting and he will be free to ask her. Just knowing that her feelings can be returned must be heaven to Amy.

message 105:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 22, 2020 06:36AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Robin - "Clennam "watching out the night" reminded me of the night Amy and Maggie spent outside at their "party" ..."

Yes, good analogy. He certainly feels alone and friendless. Actually he is more depressed than we might have expected. Just think how many have come to cheer him up, or ask about him. They are all trying to be kind in their own ways.

Young John, despite his passive-aggressive behaviour, gives him the room he thinks Arthur would like best, and also brings him the choicest food, including something fresh and green. He tries his best to take care of Arthur. Mr. and Mrs. Plornish visit him - and Mrs. Plornish would have tried to to become a regular visitor, had Arthur allowed it. Ferdinand Barnacle arrives to offer his advice on how to view the Circumlocution office - and how to stay out of prison. Mr. Rugg visits, Mr. Pancks visits ... So many people come to visit Arthur, or at least to ask about him at the gate of the prison.

Everyone, it seems, cares about him except his mother. Her heart seems even more "flinty" than Flintwinch's! She has offered Arthur nothing but criticism, and warnings not to judge her. It seems almost inconceivable that she would not at least sent Flintwinch to find out how he is, or to offer the money to get him out of the Marshalsea. But no. Her heart is made of stone.

Is this what is depressing Arthur? Somehow I doubt it, despite his efforts to get closer to her. Like Pancks is feeling with regard to Arthur, Arthur is consumed by guilt for Daniel Doyce. And yet it is not this which we are told is in his every thought. It is something, someone, else.

Sara said, "How does he declare his love for Amy and ask to marry her now, when he is in prison, when he failed to recognize his love for her before and never asked to marry her then." and I'm sure this is right. Perhaps it is an English trait; I don't know, but it might be. It is not forthright, direct, or even as honest as other cultures pride themselves on. But it is very English: understated, and meant to be honourable and kind. In situations like this we tend to be our own worst enemy.

John Chivery too, is trying his hardest to be honourable. I've said before that like Katy, I always feel sorry for young John Chivery, who in the end was truly chiv-alrous. It occurs to me that Charles Dickens has perhaps selected another appropriate name for us there.

So now it's time to move on to the penultimate episode, and actually the final installment of Little Dorrit, because the last one was a double issue.

It was numbers 19 and 20, which comprised a double issue of 4 chapters, in June 1857.

Yes, good analogy. He certainly feels alone and friendless. Actually he is more depressed than we might have expected. Just think how many have come to cheer him up, or ask about him. They are all trying to be kind in their own ways.

Young John, despite his passive-aggressive behaviour, gives him the room he thinks Arthur would like best, and also brings him the choicest food, including something fresh and green. He tries his best to take care of Arthur. Mr. and Mrs. Plornish visit him - and Mrs. Plornish would have tried to to become a regular visitor, had Arthur allowed it. Ferdinand Barnacle arrives to offer his advice on how to view the Circumlocution office - and how to stay out of prison. Mr. Rugg visits, Mr. Pancks visits ... So many people come to visit Arthur, or at least to ask about him at the gate of the prison.

Everyone, it seems, cares about him except his mother. Her heart seems even more "flinty" than Flintwinch's! She has offered Arthur nothing but criticism, and warnings not to judge her. It seems almost inconceivable that she would not at least sent Flintwinch to find out how he is, or to offer the money to get him out of the Marshalsea. But no. Her heart is made of stone.

Is this what is depressing Arthur? Somehow I doubt it, despite his efforts to get closer to her. Like Pancks is feeling with regard to Arthur, Arthur is consumed by guilt for Daniel Doyce. And yet it is not this which we are told is in his every thought. It is something, someone, else.

Sara said, "How does he declare his love for Amy and ask to marry her now, when he is in prison, when he failed to recognize his love for her before and never asked to marry her then." and I'm sure this is right. Perhaps it is an English trait; I don't know, but it might be. It is not forthright, direct, or even as honest as other cultures pride themselves on. But it is very English: understated, and meant to be honourable and kind. In situations like this we tend to be our own worst enemy.

John Chivery too, is trying his hardest to be honourable. I've said before that like Katy, I always feel sorry for young John Chivery, who in the end was truly chiv-alrous. It occurs to me that Charles Dickens has perhaps selected another appropriate name for us there.

So now it's time to move on to the penultimate episode, and actually the final installment of Little Dorrit, because the last one was a double issue.

It was numbers 19 and 20, which comprised a double issue of 4 chapters, in June 1857.

message 106:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 22, 2020 06:51AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

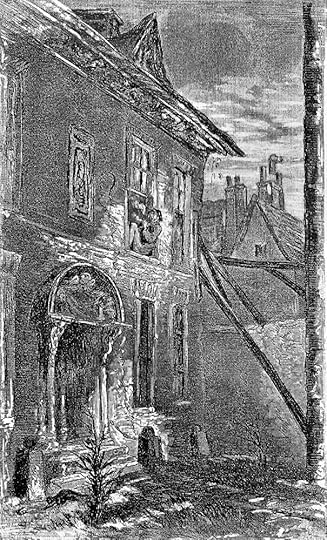

Book II: Chapter 30 - (first post)

This first chapter is the longest and most complex in the whole book! It takes up 2 comments here, I'm afraid. But it's the one with most of the answers :)

This chapter titled “Closing In” begins with Blandois, Mr. Baptist, and Mr. Pancks making their way to the Clennam house. Blandois is his swaggering self, and takes the lead, clanking straight up-stairs to Mrs. Clennam’s room:

“Although her unchanging black dress was in every plait precisely as of old, and her unchanging attitude was rigidly preserved,”

she seems to expect Blandois, asking him who the two men are. He tells her that they are friends of “your son the prisoner”. Mrs. Clennam is angry, and tells them to leave. Mr. Pancks tells her they are glad to go; that they had agreed to bring Blandois to the door on Arthur’s behalf, but now they are glad to get away from him. The world would be a better place without him.

Pancks says that he is the one responsible for Arthur’s being in prison, although he doesn’t understand it because his calculations for the “investment”(he does not say speculation) had been sound. He says that if Arthur had not been in prison—and sick—he would be there himself, and that if he were, he would tell Affery to tell her dreams.

In the meantime Flintwinch has recognised Mr. Baptist (Cavalletto). When he and Pancks leave, as asked, Flinwinch and Mrs. Clennam exchange a glance. Flintwinch tries to send Affery away, but surprisingly she objects:

“No, I won’t, Jeremiah—no, I won’t—no, I won’t! I won’t go! I’ll stay here. I’ll hear all I don’t know, and say all I know. I will, at last, if I die for it. I will, I will, I will, I will!”

When Flintwinch makes to threaten her, Affery tells him that if he comes any nearer to her, she will scream until she rouses the entire neighbourhood, enough to wake the dead. Mrs. Clennam tells him to leave her alone. Things are closing in anyway and she may stay. She asks Affery why she is turning against her—and how she hopes this will help Arthur.

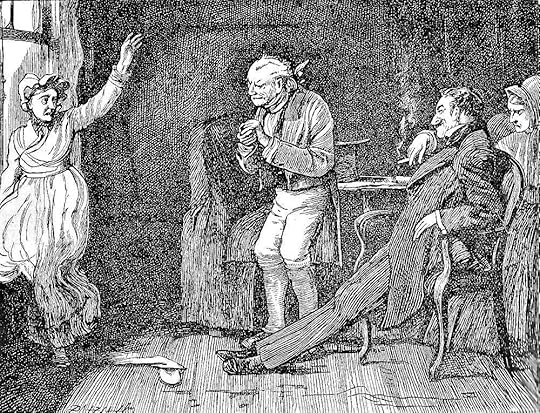

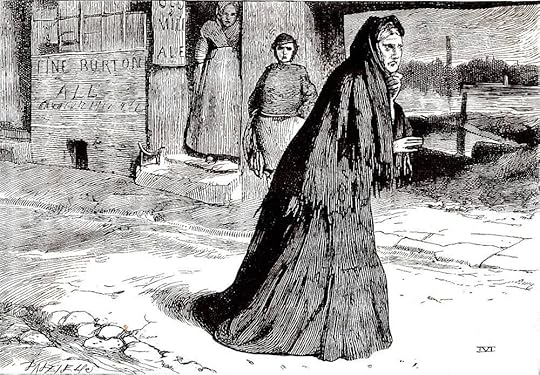

'In a Moment Affery had Thrown Down the Stocking' - James Mahoney

Affery is confused, but still defiant. Mrs. Clennam has a hard, set face. Flintwinch is barely suppressing his fury with Affery. Blandois alone is enjoying himself, behaving with mock exaggerated gallantry. He refers to himself now as “Rigaud Blandois”. Because Mrs. Clennam and Flintwinch had not fallen in with his plans as easily as he would wish, he had decided to teach them a lesson:

“Playfully, I become as one slain and hidden”

but he had been brought back. Blandois reminds Mrs. Clennam that he had been offering to sell her something which could compromise her, for £1,000 on his first visit, but now he wants £2,000. First though he demands payment for his hotel bill, which they had promised, in case they end up “at daggers’ points”. Flintwinch counts out the money into his hand. And now we get a game of cat and mouse between Blandois and Mrs. Clennam. First she says that he might have a paper, or papers, which she would be willing to buy—although, she insists, she is not a rich woman, and her means are scanty. She tells Flintwich to say nothing, but to let Blandois speak:

“You must speak explicitly, or you may go where you will, and do what you will. It is better to be torn to pieces at a spring, than to be a mouse at the caprice of such a cat.”

Blandois begins by saying it is:

“A history of a strange marriage, and a strange mother, and a revenge, and a suppression”

and proceeds in this way, distilling little bits of information:

“There live here, let us suppose, an uncle and nephew. The uncle, a rigid old gentleman of strong force of character; the nephew, habitually timid, repressed, and under constraint.”

At this Affery bursts out, saying that it is Arthur’s father and his uncle:

“I’ve heerd in my dreams that Arthur’s father was a poor, irresolute, frightened chap, who had had everything but his orphan life scared out of him when he was young, and that he had no voice in the choice of his wife even, but his uncle chose her. There she sits!”

Blandois is pleased. This is going well. But:

“Mrs Clennam’s face had changed. There was a remarkable darkness of colour on it, and the brow was more contracted.”

Blandois continues his story, in which the newlyweds return to the house, and to Flintwinch. Soon, he says, the lady makes a discovery, and “full of anger, full of jealousy, full of vengeance, she forms—see you, madame!—a scheme of retribution” upon both her husband and another. And Affery bursts in again, inadvertently supplying a prompt which Blandois had been waiting for, as she recalls when Flintwinch said that:

“you were not—and you stopped him. He was going to say that you were not—what? I know already, but I want a little confidence from you. How, then? You are not what?’

She tried again to repress herself, but broke out vehemently, ‘Not Arthur’s mother!’“

And now Mrs. Clennam cannot bear to let Blandois tell any more of the story:

“With the set expression of her face all torn away by the explosion of her passion, and with a bursting, from every rent feature, of the smouldering fire so long pent up, she cried out: ‘I will tell it myself! I will not hear it from your lips, and with the taint of your wickedness upon it. Since it must be seen, I will have it seen by the light I stood in. Not another word. Hear me!’”

Flintwinch does not think this is a good idea, and that “you had better leave Mr Rigaud, Mr Blandois, Mr Beelzebub, to tell it in his own way.”

But Mrs. Clennam is resolved. She tells of her childhood, of “wholesome repression, punishment, and fear. The corruption of our hearts, the evil of our ways, the curse that is upon us, the terrors that surround us—these were the themes of my childhood.”

When the old uncle, Mr. Gilbert Clennam had put forward his orphaned nephew to Mrs. Clennam’s father as a suitable husband for her, she was told that her husband-to-be’s bringing-up had been, like hers, one of severe restraint, and that his uncle’s house had likewise protected him from “the contagion of the irreligious and dissolute”.

However, within a year of their marriage, Mrs. Clennam:

“found my husband … to have sinned against the Lord and outraged me by holding a guilty creature in my place”.

She knew because of how she had been brought up, that it was up to her to decide and carry out their punishment:

““Do not forget.” It spoke to me like a voice from an angry cloud. Do not forget the deadly sin, do not forget the appointed discovery, do not forget the appointed suffering.”

Mr. Clennam had sent his wife the watch with the initials D.N.F. when he was dying, but she knew that it meant something else to her. She remembers.

She had forced her husband to give up his lover, and the young woman wanted to know how she could repent. Mrs. Clennam had told her:

“You have a child; I have none. You love that child. Give him to me. He shall believe himself to be my son, and he shall be believed by every one to be my son.”

She would never see her own son any more, nor her lover, but since she had lost the means which Mr. Clennam had provided for her, Mrs. Clennam would pay for what she needed.

“She was then free to bear her load of guilt in secret, and to break her heart in secret; and through such present misery … to purchase her redemption from endless misery, if she could.”

Blandois suspects that Mrs. Clennam is justifying her actions, which were truthfully full of an “insatiable vengeance”, but she vehemently denies it. And the story has just begun.

She had brought the other woman’s child (Arthur) up in fear and trembling, because this was the way she had been taught was right, and also to absolve his parents’ sins. She and her husband lived on opposite sides of the world. The woman whose child she had taken lost her mind, the: “stings of an awakened conscience drove her mad”, and she remained that way for her whole life.

Blandois is getting impatient. He knows all this. It is time to get to the money. He tells the substance of the will of Mr. Gilbert Clennam:

“One thousand guineas to the little beauty you slowly hunted to death. One thousand guineas to the youngest daughter her patron might have at fifty, or (if he had none) brother’s youngest daughter, on her coming of age, “as the remembrance his disinterestedness may like best, of his protection of a friendless young orphan girl.” Two thousand guineas.”

He also knows that there was an addition to the will which had been added by a lady … But Mrs. Clennam wants to tell this herself. She is so agitated that she is moving her hand which had been immobile for fifteen years, and in defiance of her paralysis, almost struggling to her feet. Blandois accuses her:

“Lies, lies, lies. You know you suppressed the deed and kept the money” but she will not accept that her motive had been money. She is not like those who were imprisoned with him: “stabbers and thieves”.

But Mr. Gilbert Clennam had had a change of heart, as he lay dying.

We know that Frederick Dorrit used to teach music, and we learn now that the young woman had been one of his singing pupils. This is how Arthur’s father had first met her, in search of “those accursed snares which are called the Arts”, away from his strict and loveless marriage.

Arthur’s father knew that his wife had suppressed the addition to his uncle’s will, although, as Flintwinch reminds her, he had not agreed with doing so. Mrs. Clennam does not care. It was better to keep the papers close to her, although she had not seen any reason to bring them to light. The woman had long been dead, her husband was dead, Frederick Dorrit was ruined, and had no daughter. She had found the niece (Little Dorrit): “and what I did for her, was better for her far than the money of which she would have had no good.”

(continued in next post)

This first chapter is the longest and most complex in the whole book! It takes up 2 comments here, I'm afraid. But it's the one with most of the answers :)

This chapter titled “Closing In” begins with Blandois, Mr. Baptist, and Mr. Pancks making their way to the Clennam house. Blandois is his swaggering self, and takes the lead, clanking straight up-stairs to Mrs. Clennam’s room:

“Although her unchanging black dress was in every plait precisely as of old, and her unchanging attitude was rigidly preserved,”

she seems to expect Blandois, asking him who the two men are. He tells her that they are friends of “your son the prisoner”. Mrs. Clennam is angry, and tells them to leave. Mr. Pancks tells her they are glad to go; that they had agreed to bring Blandois to the door on Arthur’s behalf, but now they are glad to get away from him. The world would be a better place without him.

Pancks says that he is the one responsible for Arthur’s being in prison, although he doesn’t understand it because his calculations for the “investment”(he does not say speculation) had been sound. He says that if Arthur had not been in prison—and sick—he would be there himself, and that if he were, he would tell Affery to tell her dreams.

In the meantime Flintwinch has recognised Mr. Baptist (Cavalletto). When he and Pancks leave, as asked, Flinwinch and Mrs. Clennam exchange a glance. Flintwinch tries to send Affery away, but surprisingly she objects:

“No, I won’t, Jeremiah—no, I won’t—no, I won’t! I won’t go! I’ll stay here. I’ll hear all I don’t know, and say all I know. I will, at last, if I die for it. I will, I will, I will, I will!”

When Flintwinch makes to threaten her, Affery tells him that if he comes any nearer to her, she will scream until she rouses the entire neighbourhood, enough to wake the dead. Mrs. Clennam tells him to leave her alone. Things are closing in anyway and she may stay. She asks Affery why she is turning against her—and how she hopes this will help Arthur.

'In a Moment Affery had Thrown Down the Stocking' - James Mahoney

Affery is confused, but still defiant. Mrs. Clennam has a hard, set face. Flintwinch is barely suppressing his fury with Affery. Blandois alone is enjoying himself, behaving with mock exaggerated gallantry. He refers to himself now as “Rigaud Blandois”. Because Mrs. Clennam and Flintwinch had not fallen in with his plans as easily as he would wish, he had decided to teach them a lesson:

“Playfully, I become as one slain and hidden”

but he had been brought back. Blandois reminds Mrs. Clennam that he had been offering to sell her something which could compromise her, for £1,000 on his first visit, but now he wants £2,000. First though he demands payment for his hotel bill, which they had promised, in case they end up “at daggers’ points”. Flintwinch counts out the money into his hand. And now we get a game of cat and mouse between Blandois and Mrs. Clennam. First she says that he might have a paper, or papers, which she would be willing to buy—although, she insists, she is not a rich woman, and her means are scanty. She tells Flintwich to say nothing, but to let Blandois speak:

“You must speak explicitly, or you may go where you will, and do what you will. It is better to be torn to pieces at a spring, than to be a mouse at the caprice of such a cat.”

Blandois begins by saying it is:

“A history of a strange marriage, and a strange mother, and a revenge, and a suppression”

and proceeds in this way, distilling little bits of information:

“There live here, let us suppose, an uncle and nephew. The uncle, a rigid old gentleman of strong force of character; the nephew, habitually timid, repressed, and under constraint.”

At this Affery bursts out, saying that it is Arthur’s father and his uncle:

“I’ve heerd in my dreams that Arthur’s father was a poor, irresolute, frightened chap, who had had everything but his orphan life scared out of him when he was young, and that he had no voice in the choice of his wife even, but his uncle chose her. There she sits!”

Blandois is pleased. This is going well. But:

“Mrs Clennam’s face had changed. There was a remarkable darkness of colour on it, and the brow was more contracted.”

Blandois continues his story, in which the newlyweds return to the house, and to Flintwinch. Soon, he says, the lady makes a discovery, and “full of anger, full of jealousy, full of vengeance, she forms—see you, madame!—a scheme of retribution” upon both her husband and another. And Affery bursts in again, inadvertently supplying a prompt which Blandois had been waiting for, as she recalls when Flintwinch said that:

“you were not—and you stopped him. He was going to say that you were not—what? I know already, but I want a little confidence from you. How, then? You are not what?’

She tried again to repress herself, but broke out vehemently, ‘Not Arthur’s mother!’“

And now Mrs. Clennam cannot bear to let Blandois tell any more of the story:

“With the set expression of her face all torn away by the explosion of her passion, and with a bursting, from every rent feature, of the smouldering fire so long pent up, she cried out: ‘I will tell it myself! I will not hear it from your lips, and with the taint of your wickedness upon it. Since it must be seen, I will have it seen by the light I stood in. Not another word. Hear me!’”

Flintwinch does not think this is a good idea, and that “you had better leave Mr Rigaud, Mr Blandois, Mr Beelzebub, to tell it in his own way.”

But Mrs. Clennam is resolved. She tells of her childhood, of “wholesome repression, punishment, and fear. The corruption of our hearts, the evil of our ways, the curse that is upon us, the terrors that surround us—these were the themes of my childhood.”

When the old uncle, Mr. Gilbert Clennam had put forward his orphaned nephew to Mrs. Clennam’s father as a suitable husband for her, she was told that her husband-to-be’s bringing-up had been, like hers, one of severe restraint, and that his uncle’s house had likewise protected him from “the contagion of the irreligious and dissolute”.

However, within a year of their marriage, Mrs. Clennam:

“found my husband … to have sinned against the Lord and outraged me by holding a guilty creature in my place”.

She knew because of how she had been brought up, that it was up to her to decide and carry out their punishment:

““Do not forget.” It spoke to me like a voice from an angry cloud. Do not forget the deadly sin, do not forget the appointed discovery, do not forget the appointed suffering.”

Mr. Clennam had sent his wife the watch with the initials D.N.F. when he was dying, but she knew that it meant something else to her. She remembers.

She had forced her husband to give up his lover, and the young woman wanted to know how she could repent. Mrs. Clennam had told her:

“You have a child; I have none. You love that child. Give him to me. He shall believe himself to be my son, and he shall be believed by every one to be my son.”

She would never see her own son any more, nor her lover, but since she had lost the means which Mr. Clennam had provided for her, Mrs. Clennam would pay for what she needed.

“She was then free to bear her load of guilt in secret, and to break her heart in secret; and through such present misery … to purchase her redemption from endless misery, if she could.”

Blandois suspects that Mrs. Clennam is justifying her actions, which were truthfully full of an “insatiable vengeance”, but she vehemently denies it. And the story has just begun.

She had brought the other woman’s child (Arthur) up in fear and trembling, because this was the way she had been taught was right, and also to absolve his parents’ sins. She and her husband lived on opposite sides of the world. The woman whose child she had taken lost her mind, the: “stings of an awakened conscience drove her mad”, and she remained that way for her whole life.

Blandois is getting impatient. He knows all this. It is time to get to the money. He tells the substance of the will of Mr. Gilbert Clennam:

“One thousand guineas to the little beauty you slowly hunted to death. One thousand guineas to the youngest daughter her patron might have at fifty, or (if he had none) brother’s youngest daughter, on her coming of age, “as the remembrance his disinterestedness may like best, of his protection of a friendless young orphan girl.” Two thousand guineas.”

He also knows that there was an addition to the will which had been added by a lady … But Mrs. Clennam wants to tell this herself. She is so agitated that she is moving her hand which had been immobile for fifteen years, and in defiance of her paralysis, almost struggling to her feet. Blandois accuses her:

“Lies, lies, lies. You know you suppressed the deed and kept the money” but she will not accept that her motive had been money. She is not like those who were imprisoned with him: “stabbers and thieves”.

But Mr. Gilbert Clennam had had a change of heart, as he lay dying.

We know that Frederick Dorrit used to teach music, and we learn now that the young woman had been one of his singing pupils. This is how Arthur’s father had first met her, in search of “those accursed snares which are called the Arts”, away from his strict and loveless marriage.

Arthur’s father knew that his wife had suppressed the addition to his uncle’s will, although, as Flintwinch reminds her, he had not agreed with doing so. Mrs. Clennam does not care. It was better to keep the papers close to her, although she had not seen any reason to bring them to light. The woman had long been dead, her husband was dead, Frederick Dorrit was ruined, and had no daughter. She had found the niece (Little Dorrit): “and what I did for her, was better for her far than the money of which she would have had no good.”

(continued in next post)

message 107:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 22, 2020 07:36AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Book II: Chapter 30 (concluding post)

Blandois continues to goad her, reminding her without mentioning names, that when “our friend the prisoner—jail-comrade of my soul” (Arthur) came home from abroad, the paper was in the house, and:

“The little singing-bird that never was fledged, was long kept in a cage by a guardian of your appointing, well enough known to our old intriguer here.”

Affery fills in more of the story, terrified though she is by Flintwinch, who is so violent that he has to be restrained by Blandois:

“The person as this man has spoken of, was Jeremiah’s own twin brother; and he was here in the dead of the night, on the night when Arthur come home, and Jeremiah with his own hands give him this paper, along with I don’t know what more, and he took it away in an iron box—Help! Murder! Save me from Jere-mi-ah!”

Blandois explains that he had met Flintwinch’s twin brother in Antwerp, where he smoked and drank himself to death:

“What does it matter how I took possession of the papers in his iron box?”

He is delighted to find he knows more than both Mrs. Clennam and Flintwinch:

“Permit me, Madame Clennam who suppresses, to present Monsieur Flintwinch who intrigues.”

Flintwinch, already furious with Affery, now uses this opportunity to give a long diatribe against Mrs. Clennam, as a most “opinionated and obstinate of women” full of “pride … all slight, and spite, and power, and unforgiveness” and yet maintaining her right to condemn and judge as a “servant and a minister” of her religion.

“That may be your religion, but it’s my gammon.”

He said he had told her how foolish it was to hang on to the papers, all these years, even when Arthur was coming home, and may find them for himself. And at last she told him where she had put them, among the old ledgers in the cellars. But she would not have them burnt on a Sunday.

This annoyed Flintwinch so much that now that he knew where the papers were, he had a look for himself, and secretly substituted another paper for one of them, before they were burnt.

Flintwinch goes on to explain about his twin brother, Ephraim, who was a keeper in a lunatic asylum. It was the same lunatic asylum where Arthur’s mother had been kept:

“she had been always writing, incessantly writing,—mostly letters of confession to you, and Prayers for forgiveness.”

Ephraim had passed the letters on to Flintwinch, who read them from time to time, and kept them locked up in a box. When Arthur was coming home from abroad, Flintwinch needed to get all the papers—both those to do with the will, and these letters—out of the house. Meanwhile, Ephraim had got into debt, and was calling on Flintwinch for a little money, before fleeing to Antwerp. That was the very evening of Affery’s first dream, when she saw Flintwinch give his twin brother the double-locked box of papers for safe keeping. When Flintwinch then tried to get the papers back, he had no reply, and now says he knows why. (Blandois had stolen the box of papers from Ephraim after he died in Antwerp).

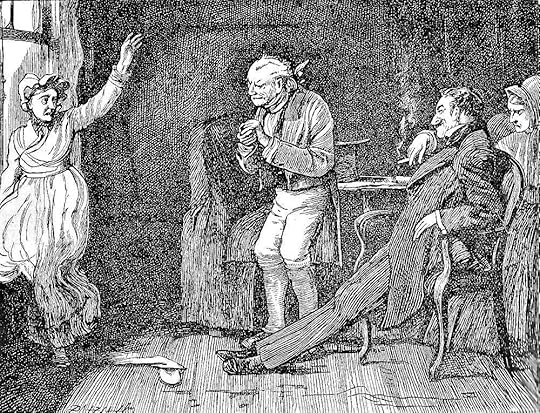

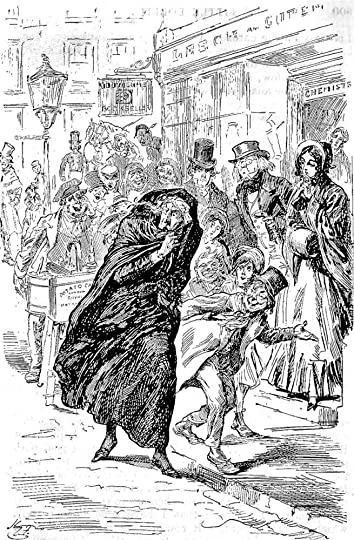

'Closing In' - F.O.C.Darley

Mrs. Clennam says that the box will never be worth nearly as much to anyone else, and that she has not enough money to pay what Blandois wants. What can she pay him in the meantime? But Blandois has a final twist.

He has left the packet with Little Dorrit, saying that it is for Arthur’s sake. If it is not reclaimed before the Marshalsea closes for the night, Little Dorrit must give Arthur the packet, and he must give the second copy, which is enclosed, to her.

“as to its not bringing me, elsewhere, the price it will bring here, say then, madame, have you limited and settled the price the little niece will give—for his sake—to hush it up? Once more I say, time presses. The packet not reclaimed before the ringing of the bell to-night, you cannot buy. I sell, then, to the little girl!”

Faced with this awful prospect, Mrs. Clennam forces herself to put on outdoor clothes. Affery begs her not to go out “you’ll fall dead in the street!” She swears she doesn’t bear Mrs. Clennam any ill will, and will keep her secret, if:

“the poor thing that’s kept here secretly, you’ll let me take charge of her and be her nurse.”

Mrs. Clennam has no idea what she means, as the woman died over 20 years before, when Arthur went abroad:

“‘So much the worse,’ said Affery, with a shiver, ‘for she haunts the house, then. Who else rustles about it, making signals by dropping dust so softly? Who else comes and goes, and marks the walls with long crooked touches when we are all a-bed? Who else holds the door sometimes?’”

Mrs. Clennam is determined, and leaves the room. Affery follows, then Flintwinch. We are left with Blandois, who:

“In the hour of his triumph, his moustache went up and his nose came down, as he ogled a great beam over his head with particular satisfaction.”

Blandois continues to goad her, reminding her without mentioning names, that when “our friend the prisoner—jail-comrade of my soul” (Arthur) came home from abroad, the paper was in the house, and:

“The little singing-bird that never was fledged, was long kept in a cage by a guardian of your appointing, well enough known to our old intriguer here.”

Affery fills in more of the story, terrified though she is by Flintwinch, who is so violent that he has to be restrained by Blandois:

“The person as this man has spoken of, was Jeremiah’s own twin brother; and he was here in the dead of the night, on the night when Arthur come home, and Jeremiah with his own hands give him this paper, along with I don’t know what more, and he took it away in an iron box—Help! Murder! Save me from Jere-mi-ah!”

Blandois explains that he had met Flintwinch’s twin brother in Antwerp, where he smoked and drank himself to death:

“What does it matter how I took possession of the papers in his iron box?”

He is delighted to find he knows more than both Mrs. Clennam and Flintwinch:

“Permit me, Madame Clennam who suppresses, to present Monsieur Flintwinch who intrigues.”

Flintwinch, already furious with Affery, now uses this opportunity to give a long diatribe against Mrs. Clennam, as a most “opinionated and obstinate of women” full of “pride … all slight, and spite, and power, and unforgiveness” and yet maintaining her right to condemn and judge as a “servant and a minister” of her religion.

“That may be your religion, but it’s my gammon.”

He said he had told her how foolish it was to hang on to the papers, all these years, even when Arthur was coming home, and may find them for himself. And at last she told him where she had put them, among the old ledgers in the cellars. But she would not have them burnt on a Sunday.

This annoyed Flintwinch so much that now that he knew where the papers were, he had a look for himself, and secretly substituted another paper for one of them, before they were burnt.

Flintwinch goes on to explain about his twin brother, Ephraim, who was a keeper in a lunatic asylum. It was the same lunatic asylum where Arthur’s mother had been kept:

“she had been always writing, incessantly writing,—mostly letters of confession to you, and Prayers for forgiveness.”

Ephraim had passed the letters on to Flintwinch, who read them from time to time, and kept them locked up in a box. When Arthur was coming home from abroad, Flintwinch needed to get all the papers—both those to do with the will, and these letters—out of the house. Meanwhile, Ephraim had got into debt, and was calling on Flintwinch for a little money, before fleeing to Antwerp. That was the very evening of Affery’s first dream, when she saw Flintwinch give his twin brother the double-locked box of papers for safe keeping. When Flintwinch then tried to get the papers back, he had no reply, and now says he knows why. (Blandois had stolen the box of papers from Ephraim after he died in Antwerp).

'Closing In' - F.O.C.Darley

Mrs. Clennam says that the box will never be worth nearly as much to anyone else, and that she has not enough money to pay what Blandois wants. What can she pay him in the meantime? But Blandois has a final twist.

He has left the packet with Little Dorrit, saying that it is for Arthur’s sake. If it is not reclaimed before the Marshalsea closes for the night, Little Dorrit must give Arthur the packet, and he must give the second copy, which is enclosed, to her.

“as to its not bringing me, elsewhere, the price it will bring here, say then, madame, have you limited and settled the price the little niece will give—for his sake—to hush it up? Once more I say, time presses. The packet not reclaimed before the ringing of the bell to-night, you cannot buy. I sell, then, to the little girl!”

Faced with this awful prospect, Mrs. Clennam forces herself to put on outdoor clothes. Affery begs her not to go out “you’ll fall dead in the street!” She swears she doesn’t bear Mrs. Clennam any ill will, and will keep her secret, if:

“the poor thing that’s kept here secretly, you’ll let me take charge of her and be her nurse.”

Mrs. Clennam has no idea what she means, as the woman died over 20 years before, when Arthur went abroad:

“‘So much the worse,’ said Affery, with a shiver, ‘for she haunts the house, then. Who else rustles about it, making signals by dropping dust so softly? Who else comes and goes, and marks the walls with long crooked touches when we are all a-bed? Who else holds the door sometimes?’”

Mrs. Clennam is determined, and leaves the room. Affery follows, then Flintwinch. We are left with Blandois, who:

“In the hour of his triumph, his moustache went up and his nose came down, as he ogled a great beam over his head with particular satisfaction.”

message 108:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 22, 2020 07:41AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

There's such an atmospheric beginning to this chapter:

The last day of the appointed week touched the bars of the Marshalsea gate. Black, all night, since the gate had clashed upon Little Dorrit, its iron stripes were turned by the early-glowing sun into stripes of gold. Far aslant across the city, over its jumbled roofs, and through the open tracery of its church towers, struck the long bright rays, bars of the prison of this lower world.

And then a veritable whirlwind of information to follow! I had to read it more than once, to get it all straight in my mind.

I like that Affery shows some spirit here. And also that she moves the explanation on quite well.

So many answers to so many questions ... I really think this deserved telling over three chapters! Apologues for the length, but there wasn't anything I could really miss out, and had to make the retelling readable.

We are left with one big question. Affery has been shown to be reliable after all, and her "dreams" are not silly imaginings. So who, or what, is in the house, making these sounds which terrify her so much?

The last day of the appointed week touched the bars of the Marshalsea gate. Black, all night, since the gate had clashed upon Little Dorrit, its iron stripes were turned by the early-glowing sun into stripes of gold. Far aslant across the city, over its jumbled roofs, and through the open tracery of its church towers, struck the long bright rays, bars of the prison of this lower world.

And then a veritable whirlwind of information to follow! I had to read it more than once, to get it all straight in my mind.

I like that Affery shows some spirit here. And also that she moves the explanation on quite well.

So many answers to so many questions ... I really think this deserved telling over three chapters! Apologues for the length, but there wasn't anything I could really miss out, and had to make the retelling readable.

We are left with one big question. Affery has been shown to be reliable after all, and her "dreams" are not silly imaginings. So who, or what, is in the house, making these sounds which terrify her so much?

What a chapter! It's rather telling to me that Mrs.Clennam suddenly recovers and can walk only when it is a matter of HER reputation.

What a chapter! It's rather telling to me that Mrs.Clennam suddenly recovers and can walk only when it is a matter of HER reputation.

Thanks again Jean for all the hard work. That chapter was like trying to drink from a fire hose.

Thanks again Jean for all the hard work. That chapter was like trying to drink from a fire hose.So Arthur's father had married twice. The first was secret.

I'm not sure I follow all the codacil business but I guess ultimately Frederick was the patron for a time of Arthur's real mother before she went to the lunatic asylum (where Flitwiche's brother was a guard). And so the inheritance would have gone to Frederick, or then to Amy. Whoosh. British inheritance at that time...no wonder so many attorneys! (But it can still be very complicated if you've ever been to an estate-planning lawyer nowadays in the States.)

The line where Arthur's pretend mother and real father were farther apart in the same house than when he was in China was something.

The old the-Will-wasnt-really-burnt-in-the-fire trick!

message 111:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 22, 2020 09:37AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Mark wrote: "Thanks again Jean for all the hard work. That chapter was like trying to drink from a fire hose ..."

LOL! Yes, but you got it Mark! I really do think Charles Dickens packed too much into this chapter though. We shouldn't need to read it over and over again to understand it (and I'm not the sort of reader who can let it wash over me).

Some critics dislike Little Dorrit, saying that it is overly complicated. I hadn't particularly remembered it like that, and think Bleak House is the most complex - but this chapter is! All these middle novels are huge, with many interweaving plot lines, and his public did begin to ask for a more streamlined story. That's when he gave them Great Expectations - which still has many intriguing mysteries :)

Yet even with all this plot development, we still have a commanding description of high emotions; it's riveting stuff!

LOL! Yes, but you got it Mark! I really do think Charles Dickens packed too much into this chapter though. We shouldn't need to read it over and over again to understand it (and I'm not the sort of reader who can let it wash over me).

Some critics dislike Little Dorrit, saying that it is overly complicated. I hadn't particularly remembered it like that, and think Bleak House is the most complex - but this chapter is! All these middle novels are huge, with many interweaving plot lines, and his public did begin to ask for a more streamlined story. That's when he gave them Great Expectations - which still has many intriguing mysteries :)

Yet even with all this plot development, we still have a commanding description of high emotions; it's riveting stuff!

Bionic Jean wrote: "Robin - "Clennam "watching out the night" reminded me of the night Amy and Maggie spent outside at their "party" ..."

Bionic Jean wrote: "Robin - "Clennam "watching out the night" reminded me of the night Amy and Maggie spent outside at their "party" ..."Yes, good analogy. He certainly feels alone and friendless. Actually he is mor..."

It makes sense that Arthur is more depressed than Mr. Dorrit ever was because Arthur fells himself responsible for his own misery and that of others. Dorrit always felt he was better than his "temporary" abode and he had little thought for others, either when poor or rich.

Bionic Jean wrote: "Mark wrote: "Thanks again Jean for all the hard work. That chapter was like trying to drink from a fire hose ..."

Bionic Jean wrote: "Mark wrote: "Thanks again Jean for all the hard work. That chapter was like trying to drink from a fire hose ..."LOL! Yes, but you got it Mark! I really do think Charles Dickens p..."

Yes! Such an exciting chapter -- if you could understand it!! I had to read a couple of summaries explaining it all in easier language! That was really a lot of information packed into one chapter, explaining a lot about why Arthur's "mother" had always been so awful to him, and why she had taken on Amy as "help." Can't wait to see how it all ends :)

I chime in with the chorus: WHAT A CHAPTER! I also had to go over everything several times to try to things straight. Not as smooth of a reveal as it could have been, with so many reveals in one chapter, or partial -reveals. Still a little confused but now, I'm wondering where is Mrs. Clennam going?

I chime in with the chorus: WHAT A CHAPTER! I also had to go over everything several times to try to things straight. Not as smooth of a reveal as it could have been, with so many reveals in one chapter, or partial -reveals. Still a little confused but now, I'm wondering where is Mrs. Clennam going?

Jean, I agree that Bleak House is complicated too, but I think its central mystery is very organic. To me at least, BH seems to hold together very well.

Jean, I agree that Bleak House is complicated too, but I think its central mystery is very organic. To me at least, BH seems to hold together very well.

message 116:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 23, 2020 07:11AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Terris wrote: "I had to read a couple of summaries explaining it all in easier language!..."

Oh dear ... Wasn't mine helpful, Terris? You can find each chapter summary easily enough, by using the links at the beginning of the thread.

I've never found any online which are complete or neutral enough, (i.e. without any critical comment included in the text), allowing you to deduce things for yourself. I think it's more fun that way - and not like being back at school. That's why any commentary I make is separate - like everyone else's. If it's research, not opinion: "a little more", that is separate too.

So I would be glad to know which you used. It would save me so, so, so many hours! I was thinking this morning that I have more or less paraphrased two entire Charles Dickens novels, chapter by chapter, rather than making brief summaries. Perhaps that level of detail is not always necessary, (although for this chapter it did seem to be) so perhaps I won't do it next time.

Also, you do have to be careful of spoilers when looking at other sites :( eg. Wiki has a list of characters for most of the novels - but they are chock-a-block with spoilers, so only useful afterwards. Ditto with Charles Dickens' own Prefaces. This one we can read at the end :)

Oh dear ... Wasn't mine helpful, Terris? You can find each chapter summary easily enough, by using the links at the beginning of the thread.

I've never found any online which are complete or neutral enough, (i.e. without any critical comment included in the text), allowing you to deduce things for yourself. I think it's more fun that way - and not like being back at school. That's why any commentary I make is separate - like everyone else's. If it's research, not opinion: "a little more", that is separate too.

So I would be glad to know which you used. It would save me so, so, so many hours! I was thinking this morning that I have more or less paraphrased two entire Charles Dickens novels, chapter by chapter, rather than making brief summaries. Perhaps that level of detail is not always necessary, (although for this chapter it did seem to be) so perhaps I won't do it next time.

Also, you do have to be careful of spoilers when looking at other sites :( eg. Wiki has a list of characters for most of the novels - but they are chock-a-block with spoilers, so only useful afterwards. Ditto with Charles Dickens' own Prefaces. This one we can read at the end :)

This chapter sure explained a lot. Nothing that I expected. And now, I hate Mrs. Clennam. My gosh! How could she separate a mother and child like that. Then just go on to treat Arthur horribly.

This chapter sure explained a lot. Nothing that I expected. And now, I hate Mrs. Clennam. My gosh! How could she separate a mother and child like that. Then just go on to treat Arthur horribly.

Anne wrote: "I chime in with the chorus: WHAT A CHAPTER! I also had to go over everything several times to try to things straight. Not as smooth of a reveal as it could have been, with so many reveals in one ch..."

Anne wrote: "I chime in with the chorus: WHAT A CHAPTER! I also had to go over everything several times to try to things straight. Not as smooth of a reveal as it could have been, with so many reveals in one ch..."Good question Anne. Also, whose presence is Affery sensing in the house?

Pancks' comment about the failed investment gives me hope for Arthur's financial future. Maybe there is something fishy going on apart from Mr. Merdle's thievery.

Also, I am wondering if the open window and Affery filling in the details of the story have any significance, like perhaps someone is listening. Affery seems to have become much bolder all of a sudden.

Jean:

Jean:Your comments and summaries are extremely helpful. I am very thankful for them! You've done and astounding service for us.

I'm looking forward to reading them and everyone's comments when I begin David Copperfield after finishing Little Dorrit.

I second the opinion that your summaries are marvelous! Even after reading this chapter twice, your summary brought a few of the details into focus for me that had been still hanging on the edges of my mind refusing to settle.

I second the opinion that your summaries are marvelous! Even after reading this chapter twice, your summary brought a few of the details into focus for me that had been still hanging on the edges of my mind refusing to settle.It should not surprise me that Arthur's mother is not his mother. She has not had one motherly word or action toward him since he returned from China. I wonder that Arthur did not inherit all the property directed when his father died. It is normal for the male heir to inherit and the wife to simply get a settlement. What a formidable woman. I think she is on a par with Blandois morally.

I hope Affrey has the presence of mind to get out to there now. I'm afraid she would not be safe in Flintwinch's company.

Katy - I also wondered if Pancks might be right about the investment and the money might not all be truly gone.

I finally got my audio version back from the libary, so I am at chapter 14 in that. In chapter 13, Pancks says to Arthur that he needs money to help his relative, as one never knows what may happen. I'm wondering if this is just Dickens foreshadowing what has just happened or if Pancks knew Mrs Clennam had a secret?

I finally got my audio version back from the libary, so I am at chapter 14 in that. In chapter 13, Pancks says to Arthur that he needs money to help his relative, as one never knows what may happen. I'm wondering if this is just Dickens foreshadowing what has just happened or if Pancks knew Mrs Clennam had a secret?

Jean - I agree with Kathleen and Sara. I was especially grateful for your summaries of this chapter as there was so much explained and I missed some of the details.

Jean - I agree with Kathleen and Sara. I was especially grateful for your summaries of this chapter as there was so much explained and I missed some of the details.

Mrs. Clennam reminds me of Miss Havisham in Great Expectations. Both keep to themselves at the center of a web and want to punish people. Miss Havisham uses Estella and Pip to wreck her revenge, and Mrs. Clennam raises Arthur in a loveless atmosphere separate from his mother to punish both Arthur's mother and her husband.

Mrs. Clennam reminds me of Miss Havisham in Great Expectations. Both keep to themselves at the center of a web and want to punish people. Miss Havisham uses Estella and Pip to wreck her revenge, and Mrs. Clennam raises Arthur in a loveless atmosphere separate from his mother to punish both Arthur's mother and her husband.Dickens' notes about chapter XXX are sparse but include:

Tell the whole story, working it out as much as possible through Mrs. Clennam herself so as to present her character very strongly...Mrs. Clennam's immobility gradually and frightfully thawing.

Also in Dickens' notes to himself about chapter XXX he makes sure to mention that Pancks has been "debuted" by Arthur to call for Affery's dreams.

Also in Dickens' notes to himself about chapter XXX he makes sure to mention that Pancks has been "debuted" by Arthur to call for Affery's dreams.So Arthur (who has asked Affery about her dreams before and she would not say on the stairway) is the instrument of summoning Affery to help with this avalanche of reveals. So Arthur is part of Affery's sudden courage. And Affery helps to keep the snowballs rolling that propel this whole episode.

Mark wrote: "Also in Dickens' notes to himself about chapter XXX he makes sure to mention that Pancks has been "debuted" by Arthur to call for Affery's dreams.

Mark wrote: "Also in Dickens' notes to himself about chapter XXX he makes sure to mention that Pancks has been "debuted" by Arthur to call for Affery's dreams.So Arthur (who has asked Affery about her dreams ..."

Very interesting. Dickens thought dreams revealed the truth of all that Affery sees but doesn't want to sees- covering her head all the time. Sort of a Freudian idea pre-Freud.

I really recommend this printed edition of Little Dorrit by Penguin Classics. It is £8.99 or $13.00 US. And has great footnotes, Dickens' personal notes. I think I'll look for more of these if they have them for other Dickens' novels. :)

I really recommend this printed edition of Little Dorrit by Penguin Classics. It is £8.99 or $13.00 US. And has great footnotes, Dickens' personal notes. I think I'll look for more of these if they have them for other Dickens' novels. :)I was just looking some of the notes over and there is a section Dickens wrote called Perspective.

It is talking about Arthur's real mother and says

She had written numerous appeals to Mrs. Clennam. She had implored to see her son. She had left her story. They were in the box. The D. N. F. watchpaper was her working. He [Dickens was talking about Flintwinch's brother earlier in the note] died an abroad and Rigaud got the box.

So according to this note, the D. N. F. was written by Arthur's mother. I had assumed it was Arthur's father who had written it. So that handwriting would have been very recognizable by Mrs. Clennam since she had received many latter's from her.

interesting. I wonder if all that info will appear in the text soon. I haven't read today's chapter yet.

interesting. I wonder if all that info will appear in the text soon. I haven't read today's chapter yet.

Dickens notes are very interesting Mark. Thank you for providing them.

Dickens notes are very interesting Mark. Thank you for providing them.I find it interesting how many times I feel an echo of a character from another book of Dickens, but he manages to make each of them very distinct and never, ever copies of one another. That takes a LOT of skill.

I remember Arthur specifically asking Pancks to implore Affery to tell her dreams before Pancks left him in the Marshallsea, but I didn't put the significance of that until I read the note.

I remember Arthur specifically asking Pancks to implore Affery to tell her dreams before Pancks left him in the Marshallsea, but I didn't put the significance of that until I read the note.I hope I didn't give anything away. Am not sure Dickens explains more about the DNF in the novel itself.

Anne - interesting about Affery covering her head and trying to hide the truth. Her dissociative "hysteria". :)

message 130:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 23, 2020 11:37AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Mark - Thank you for all these personal notes by Charles Dickens. They are fascinating! The Penguin black-spined Classics editions are always excellent, but sadly the size of print is tricky for me.

I have actually noticed similarities between Miss Havisham and Miss Wade as well as with Mrs. Clennam! As Sara said, they are distinct personalities, nevertheless. Well spotted :)

Affery definitely propels the action in this chapter. That is very noticeable—as is the fact that she speaks simply and directly now. That helps move it along!

We learned about all Arthur's birth mother's many written appeals, and letters, in this chapter 30. It is actually far more likely that an embroidered note would be stitched by her, than by Arthur's father. Therefore, when he came to write it, Charles Dickens probably felt that he did not really need to specify this. His audience would assume it, since needlecraft was very much a female occupation in Victorian times.

Thank you all Mark, Kathleen, Sara and Jenny, for your appreciation of my summaries :) It would obviously help (me) a huge amount if Terris has found adequate ones online, but otherwise I'll keep writing them for as long as they are enjoyed, useful—and as long as I find I can :)

Kathleen - I'm delighted you'll be reading David Copperfield, and do hope you will add your own comments in the threads, as you wish and are able to.

I have actually noticed similarities between Miss Havisham and Miss Wade as well as with Mrs. Clennam! As Sara said, they are distinct personalities, nevertheless. Well spotted :)

Affery definitely propels the action in this chapter. That is very noticeable—as is the fact that she speaks simply and directly now. That helps move it along!

We learned about all Arthur's birth mother's many written appeals, and letters, in this chapter 30. It is actually far more likely that an embroidered note would be stitched by her, than by Arthur's father. Therefore, when he came to write it, Charles Dickens probably felt that he did not really need to specify this. His audience would assume it, since needlecraft was very much a female occupation in Victorian times.

Thank you all Mark, Kathleen, Sara and Jenny, for your appreciation of my summaries :) It would obviously help (me) a huge amount if Terris has found adequate ones online, but otherwise I'll keep writing them for as long as they are enjoyed, useful—and as long as I find I can :)

Kathleen - I'm delighted you'll be reading David Copperfield, and do hope you will add your own comments in the threads, as you wish and are able to.

message 131:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 23, 2020 09:54AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Book II: Chapter 31:

This chapter follows straight on from the previous one. Mrs. Clennam, for so long paralysed, is now hurrying along the streets to the Marshalsea:

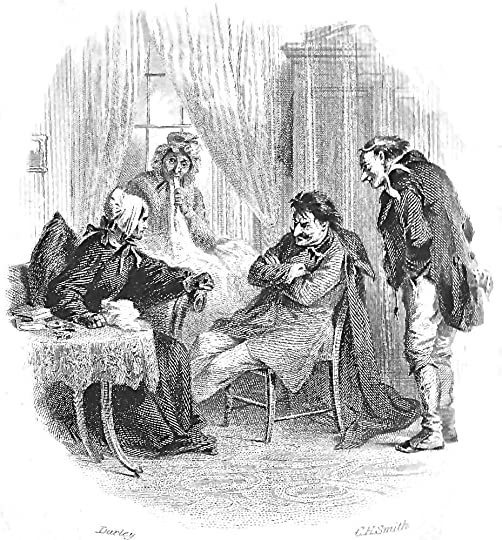

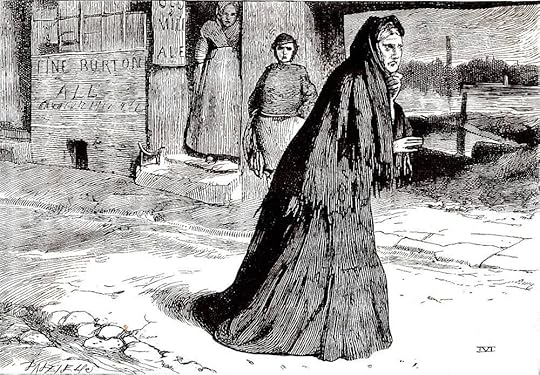

'Mrs. Affery's Dreams' - James Mahoney

Because she is conspicuously dressed in black, and looks “gaunt and of an unearthly paleness”, she attracts a lot of attention, and soon she is followed by a crowd. She is giddy and confused; things no longer seeming familiar to her, and she asks them why they are crowding her:

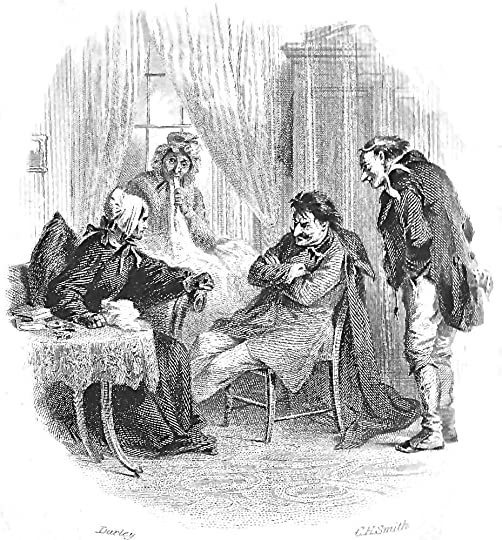

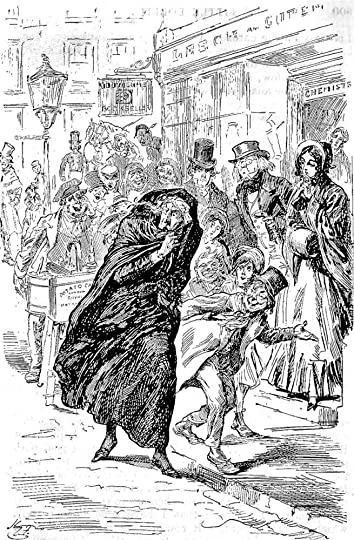

'Mrs. Clennam seeks Little Dorrit' - Harry Furniss

They tell her they are following her because she is a madwoman, and when she says she wants to find the Marshalsea, this confirms their suspicions, because it is right across the street. Young John Chivery overhears this, and seeing that she is being badgered by the crowd, he tells her he is going on duty there and will take her there.

They meet Young John’s father, and the turnkey asks her name. When she replies, Young John asks if she is Mr. Clennam’s mother. This makes her hesitate, but she decides that yes, Little Dorrit had better be told that is who is here. Mrs. Clennam is taken up to the room where Little Dorrit is staying.

“The air was heavy and hot; the closeness of the place, oppressive; and from without there arose a rush of free sounds, like the jarring memory of such things in a headache and heartache. She stood at the window, bewildered, looking down into this prison as it were out of her own different prison, when a soft word or two of surprise made her start, and Little Dorrit stood before her.”

Amy Dorrit is surprised to see her and begins to ask if she is recovered, but it is clear from Mrs. Clennam’s face that she is not strong. She brushes it aside, and asks about the packet that had been left with Amy, saying she is there to reclaim it. When Amy gives it to her, Mrs. Clennam asks if she knows what it is. Amy says she does not whereupon Mrs. Clennam tells her to read what is in the package.

“After a broken exclamation or so of wonder and of terror, she read in silence.”

Mrs. Clennam bows before Amy and asks if she understand what she has done. Amy thinks she does, but she is “so sorry, and has so much to pity” that she may not have followed it all. Mrs. Clennam vows that she will restore to Amy what she has withheld and asks if Amy can forgive her. Amy forgives her freely; she hates to see Mrs. Clennam, an old woman kneel before her, and says she can forgive her without the need for that.

Mrs. Clennam has a request. She begs Amy to keep her secret from Arthur—at least until she is dead—unless Little Dorrit thinks it is better, and will do him good to know. Amy says she will do as Mrs. Clennam asks. Mrs. Clennam decides to explain:

“I can better bear to be known to you whom I have wronged, than to the son of my enemy who wronged me.”

She says she brought Arthur up sternly, as she knew was right: “knowing that the transgressions of the parents are visited on their offspring, and that there was an angry mark upon him at his birth … that the child might work out his release in bondage and hardship.”

Mrs. Clennam insists that this was not for her own satisfaction, but for his own good. She has always known that Arthur never loved her, but he has always been considerate and deferential, and she does not want to lose his respect while she lives. Little Dorrit, she says has only known her for a little time. Now Mrs. Clennam feels she had done what she was supposed to do, to admit to Little Dorrit that she has not done her a kindness but an injury. She has set herself against evil, not against good: the evil perpetrated by her husband and Arthur’s birth mother:

“I have been an instrument of severity against sin. Have not mere sinners like myself been commissioned to lay it low in all time?”

Little Dorrit queries this, and Mrs. Clennam quotes her religious beliefs:

“Even if my own wrong had prevailed with me, and my own vengeance had moved me, could I have found no justification? None in the old days when the innocent perished with the guilty, a thousand to one? When the wrath of the hater of the unrighteous was not slaked even in blood, and yet found favour?”

But Amy Dorrit implores her not to give in to “angry feelings and unforgiving deeds”. She say that even though she has spent nearly all her life in prison, and has had very little teaching, she does not take this as her guide:

“Be guided only by the healer of the sick, the raiser of the dead, the friend of all who were afflicted and forlorn, the patient Master who shed tears of compassion for our infirmities.”

She implores Mrs. Clennam to remember the “later and better days” rather than seeking vengeance and inflicting suffering. She is certain that is the right way. The narrator says that Amy’s life and Mrs. Clennam’s precepts had been markedly different:

“In the softened light of the window, looking from the scene of her early trials to the shining sky, she was not in stronger opposition to the black figure in the shade than the life and doctrine on which she rested were to that figure’s history. It bent its head low again, and said not a word.”

The warning bell rings, and interrupts their thoughts. Mrs. Clennam tells Amy that Blandois is demanding money to hide this secret from Arthur, but that she doesn’t have the money to pay him what he wants. She can only keep the knowledge from Arthur, by buying Blandois off. He has threatened to tell Amy the truth, and Mrs. Clennam asks if Amy is willing to return with her, to show him that she already knows. Amy willingly agrees to go with her.

The summer evening is serene and beautiful. The dinginess of the smoky London air seems brighter, and the sunset still pervade the “long light films of cloud that lay at peace in the horizon … great shoots of light streamed among the early stars,” full of peace and hope. They hurry on.

“Their feet were at the gateway, when there was a sudden noise like thunder … In one swift instant the old house was before them, with the man lying smoking in the window; another thundering sound, and it heaved, surged outward, opened asunder in fifty places, collapsed, and fell. Deafened by the noise, stifled, choked, and blinded by the dust, they hid their faces and stood rooted to the spot. The dust storm, driving between them and the placid sky, parted for a moment and showed them the stars. As they looked up, wildly crying for help, the great pile of chimneys, which was then alone left standing like a tower in a whirlwind, rocked, broke, and hailed itself down upon the heap of ruin, as if every tumbling fragment were intent on burying the crushed wretch deeper.”

Mrs. Clennam drops down motionlesss upon the stones, paralysed once more, and now also having lost the the power of speech. As long as she would live, she was to be like this, apparently understanding but: “except that she could move her eyes and faintly express a negative and affirmative with her head, she lived and died a statue.”

Affery has been following, and she takes care of her mistress, as she always has done. But what of Blandois, who had been the only one to remain in the house? Many diggers work for two days round the clock, to unearth anyone who might have been inside:

“There had been a hundred people in the house at the time of its fall, there had been fifty, there had been fifteen, there had been two. Rumour finally settled the number at two; the foreigner and Mr Flintwinch.”

Finally they find:

“the dirty heap of rubbish that had been the foreigner before his head had been shivered to atoms, like so much glass, by the great beam that lay upon him, crushing him.”

But of Flintwinch, there is no sign. Rumour gets to work again, suggesting that he might have escaped via the cellar, or even been fed through a pipe. but eventually the rumours subside, and another takes their place:

“It began then to be perceived that he had been rather busy elsewhere, converting securities into as much money as could be got for them on the shortest notice”

Affery is sure that this is what has happened, and is “devoutly thankful to be quit of him”.

And what do we think happened to him? It was reported, over time, that a old Englishman, twisted in body, was often seen near the Hague, and in drinking places in Amsterdam. He calls himself “Mynheer von Flyntevynge”.

This chapter follows straight on from the previous one. Mrs. Clennam, for so long paralysed, is now hurrying along the streets to the Marshalsea:

'Mrs. Affery's Dreams' - James Mahoney

Because she is conspicuously dressed in black, and looks “gaunt and of an unearthly paleness”, she attracts a lot of attention, and soon she is followed by a crowd. She is giddy and confused; things no longer seeming familiar to her, and she asks them why they are crowding her:

'Mrs. Clennam seeks Little Dorrit' - Harry Furniss

They tell her they are following her because she is a madwoman, and when she says she wants to find the Marshalsea, this confirms their suspicions, because it is right across the street. Young John Chivery overhears this, and seeing that she is being badgered by the crowd, he tells her he is going on duty there and will take her there.

They meet Young John’s father, and the turnkey asks her name. When she replies, Young John asks if she is Mr. Clennam’s mother. This makes her hesitate, but she decides that yes, Little Dorrit had better be told that is who is here. Mrs. Clennam is taken up to the room where Little Dorrit is staying.

“The air was heavy and hot; the closeness of the place, oppressive; and from without there arose a rush of free sounds, like the jarring memory of such things in a headache and heartache. She stood at the window, bewildered, looking down into this prison as it were out of her own different prison, when a soft word or two of surprise made her start, and Little Dorrit stood before her.”

Amy Dorrit is surprised to see her and begins to ask if she is recovered, but it is clear from Mrs. Clennam’s face that she is not strong. She brushes it aside, and asks about the packet that had been left with Amy, saying she is there to reclaim it. When Amy gives it to her, Mrs. Clennam asks if she knows what it is. Amy says she does not whereupon Mrs. Clennam tells her to read what is in the package.

“After a broken exclamation or so of wonder and of terror, she read in silence.”

Mrs. Clennam bows before Amy and asks if she understand what she has done. Amy thinks she does, but she is “so sorry, and has so much to pity” that she may not have followed it all. Mrs. Clennam vows that she will restore to Amy what she has withheld and asks if Amy can forgive her. Amy forgives her freely; she hates to see Mrs. Clennam, an old woman kneel before her, and says she can forgive her without the need for that.

Mrs. Clennam has a request. She begs Amy to keep her secret from Arthur—at least until she is dead—unless Little Dorrit thinks it is better, and will do him good to know. Amy says she will do as Mrs. Clennam asks. Mrs. Clennam decides to explain:

“I can better bear to be known to you whom I have wronged, than to the son of my enemy who wronged me.”

She says she brought Arthur up sternly, as she knew was right: “knowing that the transgressions of the parents are visited on their offspring, and that there was an angry mark upon him at his birth … that the child might work out his release in bondage and hardship.”

Mrs. Clennam insists that this was not for her own satisfaction, but for his own good. She has always known that Arthur never loved her, but he has always been considerate and deferential, and she does not want to lose his respect while she lives. Little Dorrit, she says has only known her for a little time. Now Mrs. Clennam feels she had done what she was supposed to do, to admit to Little Dorrit that she has not done her a kindness but an injury. She has set herself against evil, not against good: the evil perpetrated by her husband and Arthur’s birth mother:

“I have been an instrument of severity against sin. Have not mere sinners like myself been commissioned to lay it low in all time?”

Little Dorrit queries this, and Mrs. Clennam quotes her religious beliefs:

“Even if my own wrong had prevailed with me, and my own vengeance had moved me, could I have found no justification? None in the old days when the innocent perished with the guilty, a thousand to one? When the wrath of the hater of the unrighteous was not slaked even in blood, and yet found favour?”

But Amy Dorrit implores her not to give in to “angry feelings and unforgiving deeds”. She say that even though she has spent nearly all her life in prison, and has had very little teaching, she does not take this as her guide:

“Be guided only by the healer of the sick, the raiser of the dead, the friend of all who were afflicted and forlorn, the patient Master who shed tears of compassion for our infirmities.”

She implores Mrs. Clennam to remember the “later and better days” rather than seeking vengeance and inflicting suffering. She is certain that is the right way. The narrator says that Amy’s life and Mrs. Clennam’s precepts had been markedly different:

“In the softened light of the window, looking from the scene of her early trials to the shining sky, she was not in stronger opposition to the black figure in the shade than the life and doctrine on which she rested were to that figure’s history. It bent its head low again, and said not a word.”

The warning bell rings, and interrupts their thoughts. Mrs. Clennam tells Amy that Blandois is demanding money to hide this secret from Arthur, but that she doesn’t have the money to pay him what he wants. She can only keep the knowledge from Arthur, by buying Blandois off. He has threatened to tell Amy the truth, and Mrs. Clennam asks if Amy is willing to return with her, to show him that she already knows. Amy willingly agrees to go with her.

The summer evening is serene and beautiful. The dinginess of the smoky London air seems brighter, and the sunset still pervade the “long light films of cloud that lay at peace in the horizon … great shoots of light streamed among the early stars,” full of peace and hope. They hurry on.

“Their feet were at the gateway, when there was a sudden noise like thunder … In one swift instant the old house was before them, with the man lying smoking in the window; another thundering sound, and it heaved, surged outward, opened asunder in fifty places, collapsed, and fell. Deafened by the noise, stifled, choked, and blinded by the dust, they hid their faces and stood rooted to the spot. The dust storm, driving between them and the placid sky, parted for a moment and showed them the stars. As they looked up, wildly crying for help, the great pile of chimneys, which was then alone left standing like a tower in a whirlwind, rocked, broke, and hailed itself down upon the heap of ruin, as if every tumbling fragment were intent on burying the crushed wretch deeper.”

Mrs. Clennam drops down motionlesss upon the stones, paralysed once more, and now also having lost the the power of speech. As long as she would live, she was to be like this, apparently understanding but: “except that she could move her eyes and faintly express a negative and affirmative with her head, she lived and died a statue.”

Affery has been following, and she takes care of her mistress, as she always has done. But what of Blandois, who had been the only one to remain in the house? Many diggers work for two days round the clock, to unearth anyone who might have been inside:

“There had been a hundred people in the house at the time of its fall, there had been fifty, there had been fifteen, there had been two. Rumour finally settled the number at two; the foreigner and Mr Flintwinch.”

Finally they find:

“the dirty heap of rubbish that had been the foreigner before his head had been shivered to atoms, like so much glass, by the great beam that lay upon him, crushing him.”

But of Flintwinch, there is no sign. Rumour gets to work again, suggesting that he might have escaped via the cellar, or even been fed through a pipe. but eventually the rumours subside, and another takes their place:

“It began then to be perceived that he had been rather busy elsewhere, converting securities into as much money as could be got for them on the shortest notice”

Affery is sure that this is what has happened, and is “devoutly thankful to be quit of him”.

And what do we think happened to him? It was reported, over time, that a old Englishman, twisted in body, was often seen near the Hague, and in drinking places in Amsterdam. He calls himself “Mynheer von Flyntevynge”.

message 132:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 23, 2020 09:56AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

So we now have a third castle which has collapsed. And so dramatically! First was the Dorrit’s castle, then Mr. Merdle’s castle—and now the Clennams’ castle. And this is no mere metaphor this time, but a literal collapse of a huge old house, which had been foretold right from the start, by a silly, dreaming, terrified old woman.

The descriptive writing in this chapter is superb!

The descriptive writing in this chapter is superb!

message 133:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 23, 2021 02:41PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

And a little more …

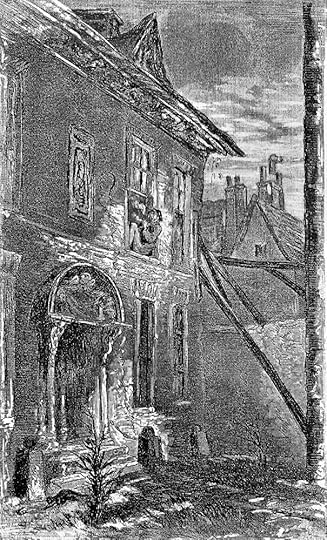

Here is a third illustration: Phiz’s illustration “Damocles”:

This is apparently the last of the “dark plates” in any novel by Charles Dickens. Cavalletto running away from Blandois was very atmospheric, but this is one of the most powerful. The title: a Classical allusion, is supremely ironic. Blandois thinks of himself as wielding the sword of Damocles, over the head of Jeremiah Flintwinch and Mrs. Clennam, and is about to lower the blade. He is a cunning blackmailer and confidence trickster. In fact though, he is the one in the very bad situation.

At the very end of the previous Chapter 30, “Closing In,” Blandois believed he had triumphed:

“In the hour of his triumph, his moustache went up and his nose came down, as he ogled a great beam over his head with particular satisfaction.”

But this beam above his head which he stares up at, as he sits smoking so nonchalantly in the upstairs window, represents the sword of Damocles. It is about to descend on him as the building collapses about him.

A wider interpretation of this allusion is the decaying atmosphere and moral collapse of society. The story which began in the prison at Marseilles thirty years ago, now ends with Arthur Clennam’s fortune engulfed in the collapse of Merdle’s financial empire. It has been shown to be a mere house of cards, as rotten as the dilapidated Clennam mansion.

Two small details of this illustration, if you can see them, show stones falling from the eaves, and a mangy cat fleeing from the scene. This is interesting, because so far we have not been told directly what is about to happen. That comes near the end of the next chapter. However we have read all Affery’s forebodings.

One critic has noticed that Phiz added details which link this scene, and the Clennam house, with themes in Bleak House, which Charles Dickens had written 3 years earlier.

The crude supports holding up this house are the same as those Phiz drew for “Tom All Alone’s”, the disease-ridden slum at the heart of the novel. It is "in Chancery"; i.e. in a hopeless legal situation with no end, a little like the Circumlocution office. This hints at a connection between the middle-class acquisitive work-ethic of Mrs. Clennam, and that in Bleak House.

Here is a third illustration: Phiz’s illustration “Damocles”: