The Old Curiosity Club discussion

David Copperfield

>

DC, Chp. 01-03

Chapter 02 once more shows Dickens's skills as a writer: With a few strokes of his brush, the first person narrator gives us an impression of the world of his childhood describing, from a child's view, the inside of the house, the church services, the outside of the house and the churchyard where his father's body lies. All this is done by jumping from one association to another and by giving minute details. It's simply great writing!!! [I am normally very stingy when it comes to using exclamation marks, as I think them bad style, but here my enthusiasm got the better of me.]

Quite aptly for an autobiography, David also muses on the workings of memory:

This is probably done with a view to forestalling criticism as to how a mere child could remember all those vivid details; at another point David concedes that he is not too sure about the dates, though.

For all the idyllic peacefulness, yet there is trouble ahead in the form of Mr. Murdstone, the new suitor of his mother. David gives a very impressive description of Mr. Murdstone, dwelling on his memories from a ride with him, when he had time to study his face from very near:

Not very reassuring. It also becomes clear that David's mother, Clara, is very vain and easy to influence, as when she takes obvious pleasure in being called “bewitching”, “pretty” or a “little widow” by Mr. Murdstone's friends. Now, being called “a little widow” is quite respectless, I should say, and it reminded me of Sir Mulberry Hawk's going on about “Little Kate Nickleby”, and what a sound thrashing Nicholas gave Sir Mulberry for this speech.

Obviously, Peggotty does not savour the prospect of seeing Mr. Murdstone as Clara's new husband, and she even takes the liberty to expostulate with her mistress. Mrs. Copperfield's reaction to these expostulations are very conclusive as to her character.

Finally, Mr. Murdstone seems to have reached his aim since one day Peggotty invites David to visit her brother in Yarmouth for a fortnight. Clearly, this is a scheme for getting David out of the way for the wedding between Murdstone and Mrs. Copperfield, who seems to have fallen for Murdstone's good looks.

Quite aptly for an autobiography, David also muses on the workings of memory:

”This may be fancy, though I think the memory of most of us can go farther back into such times than many of us suppose; just as I believe the power of observation in numbers of very young children to be quite wonderful for its closeness and accuracy. Indeed, I think that most grown men who are remarkable in this respect, may with greater propriety be said not to have lost the faculty, than to have acquired it; the rather, as I generally observe such men to retain a certain freshness, and gentleness, and capacity of being pleased, which are also an inheritance they have preserved from their childhood.

I might have a misgiving that I am ‘meandering’ in stopping to say this, but that it brings me to remark that I build these conclusions, in part upon my own experience of myself; and if it should appear from anything I may set down in this narrative that I was a child of close observation, or that as a man I have a strong memory of my childhood, I undoubtedly lay claim to both of these characteristics.”

This is probably done with a view to forestalling criticism as to how a mere child could remember all those vivid details; at another point David concedes that he is not too sure about the dates, though.

For all the idyllic peacefulness, yet there is trouble ahead in the form of Mr. Murdstone, the new suitor of his mother. David gives a very impressive description of Mr. Murdstone, dwelling on his memories from a ride with him, when he had time to study his face from very near:

”Mr. Murdstone and I were soon off, and trotting along on the green turf by the side of the road. He held me quite easily with one arm, and I don't think I was restless usually; but I could not make up my mind to sit in front of him without turning my head sometimes, and looking up in his face. He had that kind of shallow black eye—I want a better word to express an eye that has no depth in it to be looked into—which, when it is abstracted, seems from some peculiarity of light to be disfigured, for a moment at a time, by a cast. Several times when I glanced at him, I observed that appearance with a sort of awe, and wondered what he was thinking about so closely. His hair and whiskers were blacker and thicker, looked at so near, than even I had given them credit for being. A squareness about the lower part of his face, and the dotted indication of the strong black beard he shaved close every day, reminded me of the wax-work that had travelled into our neighbourhood some half-a-year before. This, his regular eyebrows, and the rich white, and black, and brown, of his complexion—confound his complexion, and his memory!—made me think him, in spite of my misgivings, a very handsome man. I have no doubt that my poor dear mother thought him so too.”

Not very reassuring. It also becomes clear that David's mother, Clara, is very vain and easy to influence, as when she takes obvious pleasure in being called “bewitching”, “pretty” or a “little widow” by Mr. Murdstone's friends. Now, being called “a little widow” is quite respectless, I should say, and it reminded me of Sir Mulberry Hawk's going on about “Little Kate Nickleby”, and what a sound thrashing Nicholas gave Sir Mulberry for this speech.

Obviously, Peggotty does not savour the prospect of seeing Mr. Murdstone as Clara's new husband, and she even takes the liberty to expostulate with her mistress. Mrs. Copperfield's reaction to these expostulations are very conclusive as to her character.

Finally, Mr. Murdstone seems to have reached his aim since one day Peggotty invites David to visit her brother in Yarmouth for a fortnight. Clearly, this is a scheme for getting David out of the way for the wedding between Murdstone and Mrs. Copperfield, who seems to have fallen for Murdstone's good looks.

In Chapter 3, the scene is set in Yarmouth, which David calls “the finest place in the universe” – Dickens himself spent some weeks in that town when he was working on the novel.

The narrator argues with a child's logic when he says

and his introduction into Peggotty's family – her brother Mr. Peggotty, is a fisherman, and then there are his nephew Ham, his niece Emily and his late partner's widow Mrs. Gummidge, and they all live in an ancient boat – also breathes the enthusiasm of childhood, but also Dickens's infatuation with fairy tales and an exuberant imagination:

David gives us a good idea of the dangers that beset the lives of the fishermen at that period, for we hear a good deal of relations being ”drowndead” by the sea, and there is one scene in which Little Emily shows David her fearlessness with regard to the sea that has claimed the life of her father, and David – with a view to what is yet in store for Emily – says,

This may serve as an example of how carefully Dickens had by then come to plan his novels; apparently the destinies of his characters were already very clear to him. Apart from that, it also keeps the reader interested ...

David's stay in Yarmouth is only slightly overshadowed by Mrs. Gummidge's occasional lapses into despondency and gloom, and Dickens gives us another of his character-identifying catch-phrases – indeed some of his characters seem to consist of only one catch-phrase – when Mrs. Gummdige repeatedly calls herself a ”lone lorn creetur” and protests that everything goes ”contrairy” with her. However, Dickens has a good eye for people like Mrs. Gummidge in that he has her constantly tell that she feels hardships more than other people.

There is also wonderful poetry in how David describes his happy-go-lucky days in Yarmouth when he says,

Eventually, however, David has to return home, and he arrives at The Rookery ”on a cold grey afternoon, with a dull sky, threatening rain”, only in order to find that Mr. Murdstone has become his new papa. Murdstone seems to have established firm control over the household as everything familiar to David had been changed – even his room, which was now farther removed from that of his mother –, and he also checks Clara's happiness about seeing her boy and watches the mother and son with eager eyes.

To make the fairy-tale villainy complete, David, on entering the garden, finds the always empty dog kennel inhabited by

David’s tribulations appear to have begun.

The narrator argues with a child's logic when he says

"and I could not help wondering, if the world were really as round as my geography book said, how any part of it came to be so flat. But I reflected that Yarmouth might be situated at one of the poles; which would account for it",

and his introduction into Peggotty's family – her brother Mr. Peggotty, is a fisherman, and then there are his nephew Ham, his niece Emily and his late partner's widow Mrs. Gummidge, and they all live in an ancient boat – also breathes the enthusiasm of childhood, but also Dickens's infatuation with fairy tales and an exuberant imagination:

”If it had been Aladdin's palace, roc's egg and all, I suppose I could not have been more charmed with the romantic idea of living in it. There was a delightful door cut in the side, and it was roofed in, and there were little windows in it; but the wonderful charm of it was, that it was a real boat which had no doubt been upon the water hundreds of times, and which had never been intended to be lived in, on dry land. That was the captivation of it to me. If it had ever been meant to be lived in, I might have thought it small, or inconvenient, or lonely; but never having been designed for any such use, it became a perfect abode.”

David gives us a good idea of the dangers that beset the lives of the fishermen at that period, for we hear a good deal of relations being ”drowndead” by the sea, and there is one scene in which Little Emily shows David her fearlessness with regard to the sea that has claimed the life of her father, and David – with a view to what is yet in store for Emily – says,

”The light, bold, fluttering little figure turned and came back safe to me, and I soon laughed at my fears, and at the cry I had uttered; fruitlessly in any case, for there was no one near. But there have been times since, in my manhood, many times there have been, when I have thought, Is it possible, among the possibilities of hidden things, that in the sudden rashness of the child and her wild look so far off, there was any merciful attraction of her into danger, any tempting her towards him permitted on the part of her dead father, that her life might have a chance of ending that day? There has been a time since when I have wondered whether, if the life before her could have been revealed to me at a glance, and so revealed as that a child could fully comprehend it, and if her preservation could have depended on a motion of my hand, I ought to have held it up to save her. There has been a time since—I do not say it lasted long, but it has been—when I have asked myself the question, would it have been better for little Em'ly to have had the waters close above her head that morning in my sight; and when I have answered Yes, it would have been.

This may be premature. I have set it down too soon, perhaps. But let it stand.”

This may serve as an example of how carefully Dickens had by then come to plan his novels; apparently the destinies of his characters were already very clear to him. Apart from that, it also keeps the reader interested ...

David's stay in Yarmouth is only slightly overshadowed by Mrs. Gummidge's occasional lapses into despondency and gloom, and Dickens gives us another of his character-identifying catch-phrases – indeed some of his characters seem to consist of only one catch-phrase – when Mrs. Gummdige repeatedly calls herself a ”lone lorn creetur” and protests that everything goes ”contrairy” with her. However, Dickens has a good eye for people like Mrs. Gummidge in that he has her constantly tell that she feels hardships more than other people.

There is also wonderful poetry in how David describes his happy-go-lucky days in Yarmouth when he says,

”The days sported by us, as if Time had not grown up himself yet, but were a child too, and always at play.”

Eventually, however, David has to return home, and he arrives at The Rookery ”on a cold grey afternoon, with a dull sky, threatening rain”, only in order to find that Mr. Murdstone has become his new papa. Murdstone seems to have established firm control over the household as everything familiar to David had been changed – even his room, which was now farther removed from that of his mother –, and he also checks Clara's happiness about seeing her boy and watches the mother and son with eager eyes.

To make the fairy-tale villainy complete, David, on entering the garden, finds the always empty dog kennel inhabited by

”a great dog—deep mouthed and black-haired like Him—and he was very angry at the sight of me, and sprang out to get at me.”

David’s tribulations appear to have begun.

Tristram wrote: "Now Miss Trotwood is the complete opposite of the young widow (and her late husband), in that on finding herself ill-treated by her husband, she paid her husband off and got a divorce. Interestingly, the text says she adopted her maiden name again – but if she is Mr. Copperfield's sister, her maiden name should be Copperfield, shouldn't it? Instead, she goes by the name of Trotwood ...."

She was his dad's aunt, not his sister ;-) I imagine she was his mother's sister then.

She was his dad's aunt, not his sister ;-) I imagine she was his mother's sister then.

Chapter 1, it took me a while to get into this new novel again. I read it before, and I love(d) it, but I had to pick up the slack and as I mentioned, I managed to read only snippets at a time. It works with these first chapters though. I found Betsy Trotwood very funny, and I think David's mother had made much wiser decisions if David had been a girl and Miss Trotwood had remained to bully them into respectability. It would have made for a totally different story though, and it was not to be. I'd not have wanted her as an aunt though.

Chapter 2, I had to laugh out loud at ceveral points, like with the lost sheep that was mutton and not sinner. Dickens painted a great image of how David lived the happy life of an equally naive (but it's excusable because he's a) little kid. It is clear that Peggotty is the one keeping the household running instead of letting it sink into naivity and unwise spending. Mr Murdstone starts as a bully already, and while he is shown as a man who is charismatic, he also shows his mean side as soon as he makes a point out of which hand to shake.

Chapter 3, up 'till now this chapter resonated with me the most. After D&S where I mentioned my family's origins, you can probably imagine that I can easily picture a haphazard household with a couple of people who lost almost everyone to the sea. According to the stories my great-great-grandma was a bit like Mrs. Gummidge, the loss of her son sent her into a depression, and my great-grandma had to take over the household duties. (My great-great-grandpa, who btw saw his own son drown at sea, I can picture as a kind of Mr. Peggotty. He must have been a very caring man, and he is said to make a lot of jokes. My family is all about stories and telling their memories.) So I loved this chapter, or at least the part about the Peggotty family. David's return home, and finding Mr. Murdstone there, who was so dominant and bullying and mean that David's mom wasn't even allowed to show David her love, made my blood boil.

Chapter 2, I had to laugh out loud at ceveral points, like with the lost sheep that was mutton and not sinner. Dickens painted a great image of how David lived the happy life of an equally naive (but it's excusable because he's a) little kid. It is clear that Peggotty is the one keeping the household running instead of letting it sink into naivity and unwise spending. Mr Murdstone starts as a bully already, and while he is shown as a man who is charismatic, he also shows his mean side as soon as he makes a point out of which hand to shake.

Chapter 3, up 'till now this chapter resonated with me the most. After D&S where I mentioned my family's origins, you can probably imagine that I can easily picture a haphazard household with a couple of people who lost almost everyone to the sea. According to the stories my great-great-grandma was a bit like Mrs. Gummidge, the loss of her son sent her into a depression, and my great-grandma had to take over the household duties. (My great-great-grandpa, who btw saw his own son drown at sea, I can picture as a kind of Mr. Peggotty. He must have been a very caring man, and he is said to make a lot of jokes. My family is all about stories and telling their memories.) So I loved this chapter, or at least the part about the Peggotty family. David's return home, and finding Mr. Murdstone there, who was so dominant and bullying and mean that David's mom wasn't even allowed to show David her love, made my blood boil.

I am happy to be back with Dickens and especially DC. It has been many years since reading this but I am amazed at how much I remembered and knew what was coming, at least in these early chapters.

I am happy to be back with Dickens and especially DC. It has been many years since reading this but I am amazed at how much I remembered and knew what was coming, at least in these early chapters.

These first 3 chapters are simply wonderful. There is a fairy tale-like quality to the story telling here, which makes sense since we're supposed to be looking at things from the perspective of the narrator's recollection of early childhood. I agree with Tristram that this is beautiful, consumate writing. I found myself almost surprised that Dickens could write this well:

These first 3 chapters are simply wonderful. There is a fairy tale-like quality to the story telling here, which makes sense since we're supposed to be looking at things from the perspective of the narrator's recollection of early childhood. I agree with Tristram that this is beautiful, consumate writing. I found myself almost surprised that Dickens could write this well:“The evening wind made such a disturbance just now, among some tall old elm-trees at the bottom of the garden, that neither my mother nor Miss Betsey could forbear glancing that way. As the elms bent to one another, like giants who were whispering secrets, and after a few seconds of such repose, fell into a violent flurry, tossing their wild arms about, as if their late confidences were really too wicked for their peace of mind, some weather-beaten ragged old rooks’-nests, burdening their higher branches, swung like wrecks upon a stormy sea.”

Takes your breath away. There is a density to the writing as in the best poetry. It made me think of Virginia Woolf.

And then there are the characters, those impossible puppets that only Dickens could pull off. Impossible in real life, but so alive in the world of his books. Just the names by themselves -- Betsey Trotwood, Dr. Chillip, Mr. Murdstone, Mrs. Gummidge, Peggotty --such wonderful names! paint pictures in the reader's mind.

Dickens really seems inspired in these opening chapters. Is there anything better than this in all of literature? The question is: will he manage to keep this level of inspiration up over the next 700 or so pages?

Tristram wrote: "Dear Curiosities,

Before I start summing up the major events of the first three chapters, I’d like to especially welcome all those Curiosities, for whom this is the first group read in this place...."

David Copperfield. What a wonderful, magical novel. It’s good to turn its pages again.

The first paragraph of the novel contains both a birth and a question. It tells us that the novel will be in the first person, but also warns us that there may well be events in the narrator’s life that will question how the reader should look upon the narrator. To jump to the last paragraph of the first chapter we have the mention of another David Copperfield, our narrator’s father, who is dead, and lies in “the mound above the ashes and dust that once was he without whom I had never been.” Thus, our first chapter is framed by a David Copperfield who is born and a David Copperfield who is dead.

I agree with Ulysse. Dickens’s writing in this chapter is powerful, and yet sublime. There is a fairy tale quality to the novel already beginning to be spun.

In this chapter we learn that David’s mother was an orphan, and that Betsey Trotwood was once unhappily married and is now separated from her husband. David is without a father. Peggotty does not have a husband. David Copperfield and his mother live in a home named Rookery after empty old rooks’ nests that no longer contain birds. Abandoned nests of birds and orphaned, or unattached people or abandoned people. This first chapter presents us with those who lack an intact family unit. This is a common trope in Dickens. Something tells me this novel may focus on how people find their homes.

Reading the novel this time I’m going to focus more on how David Copperfield unfolds himself to the reader. I have not been attentive enough to this in the past.

Before I start summing up the major events of the first three chapters, I’d like to especially welcome all those Curiosities, for whom this is the first group read in this place...."

David Copperfield. What a wonderful, magical novel. It’s good to turn its pages again.

The first paragraph of the novel contains both a birth and a question. It tells us that the novel will be in the first person, but also warns us that there may well be events in the narrator’s life that will question how the reader should look upon the narrator. To jump to the last paragraph of the first chapter we have the mention of another David Copperfield, our narrator’s father, who is dead, and lies in “the mound above the ashes and dust that once was he without whom I had never been.” Thus, our first chapter is framed by a David Copperfield who is born and a David Copperfield who is dead.

I agree with Ulysse. Dickens’s writing in this chapter is powerful, and yet sublime. There is a fairy tale quality to the novel already beginning to be spun.

In this chapter we learn that David’s mother was an orphan, and that Betsey Trotwood was once unhappily married and is now separated from her husband. David is without a father. Peggotty does not have a husband. David Copperfield and his mother live in a home named Rookery after empty old rooks’ nests that no longer contain birds. Abandoned nests of birds and orphaned, or unattached people or abandoned people. This first chapter presents us with those who lack an intact family unit. This is a common trope in Dickens. Something tells me this novel may focus on how people find their homes.

Reading the novel this time I’m going to focus more on how David Copperfield unfolds himself to the reader. I have not been attentive enough to this in the past.

I agree that the writing, storytelling, and fairy tale quality was very good. I enjoyed these chapters. The first person perspective is a nice change from Dickens's other books. It is more intimate, and it allows Dickens to express the child's mind better.

I agree that the writing, storytelling, and fairy tale quality was very good. I enjoyed these chapters. The first person perspective is a nice change from Dickens's other books. It is more intimate, and it allows Dickens to express the child's mind better.I like Peggoty as a character. She is warm-hearted and practical. I loved the imagery of the buttons popping off her dress when she hugged David. And the line about the lost sheep--not sinners, mutton. Lots of cute, charming stuff here. My favorite chapter was the one at the Peggoty boat house. I enjoyed the Noah's ark imagery, David's child-like observations, and his puppy love for Emily.

No matter how many times I read this book I always laugh when I read this:

In consideration of the day and hour of my birth, it was declared by the nurse, and by some sage women in the neighbourhood who had taken a lively interest in me several months before there was any possibility of our becoming personally acquainted, first, that I was destined to be unlucky in life; and secondly, that I was privileged to see ghosts and spirits; both these gifts inevitably attaching, as they believed, to all unlucky infants of either gender, born towards the small hours on a Friday night.

I need say nothing here, on the first head, because nothing can show better than my history whether that prediction was verified or falsified by the result. On the second branch of the question, I will only remark, that unless I ran through that part of my inheritance while I was still a baby, I have not come into it yet. But I do not at all complain of having been kept out of this property; and if anybody else should be in the present enjoyment of it, he is heartily welcome to keep it.

In consideration of the day and hour of my birth, it was declared by the nurse, and by some sage women in the neighbourhood who had taken a lively interest in me several months before there was any possibility of our becoming personally acquainted, first, that I was destined to be unlucky in life; and secondly, that I was privileged to see ghosts and spirits; both these gifts inevitably attaching, as they believed, to all unlucky infants of either gender, born towards the small hours on a Friday night.

I need say nothing here, on the first head, because nothing can show better than my history whether that prediction was verified or falsified by the result. On the second branch of the question, I will only remark, that unless I ran through that part of my inheritance while I was still a baby, I have not come into it yet. But I do not at all complain of having been kept out of this property; and if anybody else should be in the present enjoyment of it, he is heartily welcome to keep it.

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 02 once more shows Dickens's skills as a writer: With a few strokes of his brush, the first person narrator gives us an impression of the world of his childhood describing, from a child's v..."

Hi Tristram

David’s comments about memory are important. As I mentioned in an earlier post, one of my self-appointed tasks this reading is to pay more attention to how David’s mind and memory frame his narrative.

I’m glad you highlighted it.

Hi Tristram

David’s comments about memory are important. As I mentioned in an earlier post, one of my self-appointed tasks this reading is to pay more attention to how David’s mind and memory frame his narrative.

I’m glad you highlighted it.

Tristram wrote: "In Chapter 3, the scene is set in Yarmouth, which David calls “the finest place in the universe” – Dickens himself spent some weeks in that town when he was working on the novel.

The narrator argu..."

Oh, I love this chapter. It is so rich in character and so subtle in its presentation. It is a chapter to read with care.

Mr Peggotty's home, an upturned boat, is perfect. Within its hull are a collection of people who are all, in one way or another, orphans, widows or alone in the world, and yet how close a family they are. Within moments of David’s arrival he too is embraced by the inhabitants of the ship.

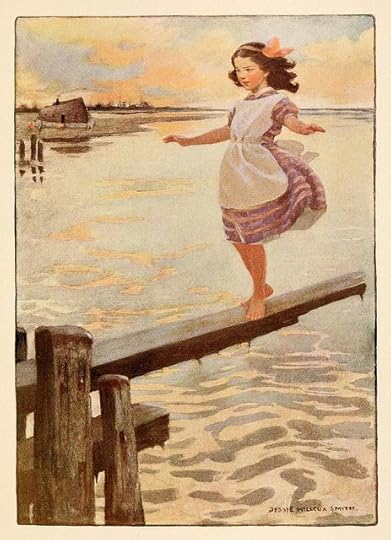

Of all the inhabitants of the upturned home Little Em’ly interests me the most. She tells us that “I’m afraid of the sea” and yet David tells the reader that she walked “too near the brink of a sort of old jetty ... and I was afraid of her falling over.” David notices her “sudden rashness” and her “wild look so far off” and muses that perhaps he “ought to have held ... up [his hand] to save her.” David then says that “[t]here has been a time since ... when I have asked myself the question.” David also comments that these thoughts “may be premature. I have set it down too soon, perhaps. But let it stand.”

How tantalizing. In these words we see David speaking from the voice of an adult, reflecting upon his life as a child, and intimating to his readers that there are events in his life yet to unfold that will be of importance concerning Em'ly. Talk about suspense!

The narrator argu..."

Oh, I love this chapter. It is so rich in character and so subtle in its presentation. It is a chapter to read with care.

Mr Peggotty's home, an upturned boat, is perfect. Within its hull are a collection of people who are all, in one way or another, orphans, widows or alone in the world, and yet how close a family they are. Within moments of David’s arrival he too is embraced by the inhabitants of the ship.

Of all the inhabitants of the upturned home Little Em’ly interests me the most. She tells us that “I’m afraid of the sea” and yet David tells the reader that she walked “too near the brink of a sort of old jetty ... and I was afraid of her falling over.” David notices her “sudden rashness” and her “wild look so far off” and muses that perhaps he “ought to have held ... up [his hand] to save her.” David then says that “[t]here has been a time since ... when I have asked myself the question.” David also comments that these thoughts “may be premature. I have set it down too soon, perhaps. But let it stand.”

How tantalizing. In these words we see David speaking from the voice of an adult, reflecting upon his life as a child, and intimating to his readers that there are events in his life yet to unfold that will be of importance concerning Em'ly. Talk about suspense!

Any time I encounter an odd name (as a parish priest and a teacher it happens often) I am reminded of Betsey Trotwood’s reaction to hearing the name Peggotty:

Any time I encounter an odd name (as a parish priest and a teacher it happens often) I am reminded of Betsey Trotwood’s reaction to hearing the name Peggotty:“”Peggotty!” repeated Miss Betsey, with some indignation. “Do you mean to say, child, that any human being has gone into a Christian church, and got herself named Peggotty?”

Does anyone else struggle with David’s mother, Clara? Each time I read these first chapters I am reminded how much I dislike her. Yes, she’s young and inexperienced as a mother - but she’s so vain and selfish. I try to remind myself that I’m looking at her with modern eyes, but every time she is cowed by Murdstone concerning showing affection for David I just want to scream. David loves her because she’s his mother...but I think she’s weak as water and inexcusably foolish.

Isaac wrote: "Any time I encounter an odd name (as a parish priest and a teacher it happens often) I am reminded of Betsey Trotwood’s reaction to hearing the name Peggotty:

“”Peggotty!” repeated Miss Betsey, wit..."

Hi Issac

Yes. Dickens’s choice of names is a constant delight to me as well. His names often act as the perfect description of the character.

Your mention of “modern eyes” as they look upon a novel set in the past is one I struggle with as well. What Victorian would think that a mere 68 years after Queen Victoria died a man would walk on the moon?

I have sympathy for David’s mother. She is very young when she marries. We learn that she was an orphan, and then a nursery-governess prior to her marriage. David’s mother was in the process of learning how to keep house and track the household finances when her husband died.

You are right that she is cowed by Murdstone and I too wish she would stand up to him. But as a child-bride who has lost her husband before the birth of her child, her life was backed into a corner. Her options were limited.

Back to names. Murdstone. If we break that up into its syllables we get Murd (merde in French?) and stone. Murdstone is a very Dickensian name that well suits his character.

“”Peggotty!” repeated Miss Betsey, wit..."

Hi Issac

Yes. Dickens’s choice of names is a constant delight to me as well. His names often act as the perfect description of the character.

Your mention of “modern eyes” as they look upon a novel set in the past is one I struggle with as well. What Victorian would think that a mere 68 years after Queen Victoria died a man would walk on the moon?

I have sympathy for David’s mother. She is very young when she marries. We learn that she was an orphan, and then a nursery-governess prior to her marriage. David’s mother was in the process of learning how to keep house and track the household finances when her husband died.

You are right that she is cowed by Murdstone and I too wish she would stand up to him. But as a child-bride who has lost her husband before the birth of her child, her life was backed into a corner. Her options were limited.

Back to names. Murdstone. If we break that up into its syllables we get Murd (merde in French?) and stone. Murdstone is a very Dickensian name that well suits his character.

Such a robust discussion already! I'm so excited to be reading with the group again. I should say at the outset that I've read Copperfield before -- twice, I think. But it's been more than 20 years, so while everything seems very familiar as I'm reading it, I'm unable to remember specific details about upcoming events. And since my last reading of Copperfield, I've read all of Dickens' other novels, some several times. So it's interesting, now being able to compare it to all the others.

Such a robust discussion already! I'm so excited to be reading with the group again. I should say at the outset that I've read Copperfield before -- twice, I think. But it's been more than 20 years, so while everything seems very familiar as I'm reading it, I'm unable to remember specific details about upcoming events. And since my last reading of Copperfield, I've read all of Dickens' other novels, some several times. So it's interesting, now being able to compare it to all the others. Perhaps it's the use of the first-person narration, but this is undoubtedly my favorite opening of a Dickens novel. No riddles, like A Tale of Two Cities or long, descriptive, atmospheric passages, like Bleak House; in Copperfield he just jumps right in to the characters, which is what I love.

As so many of you have already mentioned, there's that fairy tale quality to the writing, which is a delight. I recently read Mamie Dickens' "My Father As I Recall Him", in which she talks about his playful nature and his childlike qualities. It's easy to see here that Dickens has a keen insight into the minds of children - how they see the world, their sensibilities, and what's important to them. I regret that I've lost that insight as I've aged, and think it's a gift from God to Dickens (and a few others) who seem to never have forgotten the hopes, joys, and fears of childhood. (I don't think he necessarily applied that gift well in his parenting, but that's a discussion for another day!)

Jantine - having not read Dombey with you, I don't know the family history to which you're referring, but it sounds as if you'll bring some personal insight to our story as it goes along that will enrich the discussion for all of us. As for Aunt Betsey, she's a character, surely. I probably wouldn't want her as an aunt in real life, either, but I find her a joy to read about. With respect to your gr.gr. grandmother, it's Mrs. Gummidge that drove me nuts! It's one thing to grieve and feel things deeply. It's another to wallow in it and drag everyone around you down, while at the same time managing to be dismissive of others' emotions. I can't help but think that her victimhood is going to somehow cause trouble down the road. We'll see. (Am I the only one who imagines Mrs. Gummidge as having no teeth?)

Alissa - I love Peggoty, too, and agree that these chapters have been charming. I hope there's more of that to come, despite the ominous foreshadowing. Speaking of which....

Peter wrote: "David Copperfield and his mother live in a home named Rookery after empty old rooks’ nests that no longer contain birds. Abandoned nests of birds and orphaned, or unattached people or abandoned people. This first chapter presents us with those who lack an intact family unit. .."

This is a great observation, Peter. You're always so good at making these connections. A word about rookeries. I looked up their mythology and found this passage:

Rooks are generally regarded with bad fortune, for instance, a large group of rooks arriving in an area is said to be unlucky. However, well-established rookeries are deemed to bring good fortune and if the rooks should desert a rookery then a calamity is signaled.

Lots of negative vibes there, and I'm sure Dickens chose the name for the Copperfield's cottage carefully, even if David, Sr. did not.

Tristram, I forgive your use of so many exclamation marks - the writing in these first three chapters certainly warrants it, if anything does.

Mary Lou wrote: "Such a robust discussion already! I'm so excited to be reading with the group again. I should say at the outset that I've read Copperfield before -- twice, I think. But it's been more than 20 years..."

Hi Mary Lou

My guess is you have not lost the joy and imagination of childhood. Those feelings may have been resting for awhile, but now you have a grandchild who will help rouse your childhood delights and imagination once again. And then, when you hold your grandchild in your arms at last, well, you too will be a child again as well.

Hi Mary Lou

My guess is you have not lost the joy and imagination of childhood. Those feelings may have been resting for awhile, but now you have a grandchild who will help rouse your childhood delights and imagination once again. And then, when you hold your grandchild in your arms at last, well, you too will be a child again as well.

Ulysse wrote: "Dickens really seems inspired in these opening chapters. Is there anything better than this in all of literature? The question is: will he manage to keep this level of inspiration up over the next 700 or so pages?"

Knowing that man's way with words, I'm quite optimistic ;-)

It's cool to read how much you are enjoying the language, Ulysse. When reading Dickens, I often do it aloud when I have the chance, i.e. when there is nobody around, because I think it is like poetry, and poetry must definitely be read aloud. There are quite often passages whose rhythm makes them sound like poetry, and I think that Dickens did it on purpose.

Knowing that man's way with words, I'm quite optimistic ;-)

It's cool to read how much you are enjoying the language, Ulysse. When reading Dickens, I often do it aloud when I have the chance, i.e. when there is nobody around, because I think it is like poetry, and poetry must definitely be read aloud. There are quite often passages whose rhythm makes them sound like poetry, and I think that Dickens did it on purpose.

Bobbie wrote: "I am happy to be back with Dickens and especially DC. It has been many years since reading this but I am amazed at how much I remembered and knew what was coming, at least in these early chapters."

It's always magic to rediscover Dickens, Bobbie, however often you may have read his novels ;-)

It's always magic to rediscover Dickens, Bobbie, however often you may have read his novels ;-)

Peter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Chapter 02 once more shows Dickens's skills as a writer: With a few strokes of his brush, the first person narrator gives us an impression of the world of his childhood describing,..."

Thank you, Peter. The aspect strikes me as important because firstly, this is Dickens's first novel in which he goes away from the omniscient narrator, and secondly we are at a stage in David's life, where it is clear that the adult narrator must make sense of the memories of the narrator as a child. This must be very difficult stuff to write.

Thank you, Peter. The aspect strikes me as important because firstly, this is Dickens's first novel in which he goes away from the omniscient narrator, and secondly we are at a stage in David's life, where it is clear that the adult narrator must make sense of the memories of the narrator as a child. This must be very difficult stuff to write.

Peter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "In Chapter 3, the scene is set in Yarmouth, which David calls “the finest place in the universe” – Dickens himself spent some weeks in that town when he was working on the novel.

..."

Reading your post made me realize that we could see the happy family circle in the upturned boat as an antithesis to the incomplete family circle in The Rookery. The Pegotty family may be a family of orphans, but they all stand up for and look after each other, whereas it is doubtful that David's mother will do this trick for her own son. As Jantine mentions, if Aunt Betsey had stayed on, she might have proved helpful for Mrs. Copperfield and thwarted Mr. Murdstone's marriage plans, but as ill-luck will have it, David's being a boy is too much of a blow to her.

..."

Reading your post made me realize that we could see the happy family circle in the upturned boat as an antithesis to the incomplete family circle in The Rookery. The Pegotty family may be a family of orphans, but they all stand up for and look after each other, whereas it is doubtful that David's mother will do this trick for her own son. As Jantine mentions, if Aunt Betsey had stayed on, she might have proved helpful for Mrs. Copperfield and thwarted Mr. Murdstone's marriage plans, but as ill-luck will have it, David's being a boy is too much of a blow to her.

Isaac wrote: "Does anyone else struggle with David’s mother, Clara? Each time I read these first chapters I am reminded how much I dislike her. Yes, she’s young and inexperienced as a mother - but she’s so vain and selfish. I try to remind myself that I’m looking at her with modern eyes, but every time she is cowed by Murdstone concerning showing affection for David I just want to scream. David loves her because she’s his mother...but I think she’s weak as water and inexcusably foolish."

You have voiced my feelings about Mrs. Copperfield to a T there, Isaac!

You have voiced my feelings about Mrs. Copperfield to a T there, Isaac!

Peter wrote: "Isaac wrote: "Any time I encounter an odd name (as a parish priest and a teacher it happens often) I am reminded of Betsey Trotwood’s reaction to hearing the name Peggotty:

“”Peggotty!” repeated Mi..."

Yes, Dickens's names are classic. I always remember "Gamp is my name and Gamp is my natur'."

As to Mrs. Copperfield's options, it strikes me that she could have remained single. Her means may have been limited, but she must have been a good match in a way, for otherwise she would not have attracted Mr. Murdstone.

“”Peggotty!” repeated Mi..."

Yes, Dickens's names are classic. I always remember "Gamp is my name and Gamp is my natur'."

As to Mrs. Copperfield's options, it strikes me that she could have remained single. Her means may have been limited, but she must have been a good match in a way, for otherwise she would not have attracted Mr. Murdstone.

Mary Lou wrote: "This is a great observation, Peter. You're always so good at making these connections. A word about rookeries. I looked up their mythology and found this passage:

Rooks are generally regarded with bad fortune, for instance, a large group of rooks arriving in an area is said to be unlucky. However, well-established rookeries are deemed to bring good fortune and if the rooks should desert a rookery then a calamity is signaled."

That reminds me of the ravens in the Tower of London. Is it not said that as long as they will stay Great Britain will flourish?

Rooks are generally regarded with bad fortune, for instance, a large group of rooks arriving in an area is said to be unlucky. However, well-established rookeries are deemed to bring good fortune and if the rooks should desert a rookery then a calamity is signaled."

That reminds me of the ravens in the Tower of London. Is it not said that as long as they will stay Great Britain will flourish?

Get ready, illustrators seemed to have loved this book:

Frontispiece

Chapter 1

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

My mother was sitting by the fire, but poorly in health, and very low in spirits, looking at it through her tears, and desponding heavily about herself and the fatherless little stranger, who was already welcomed by some grosses of prophetic pins, in a drawer upstairs, to a world not at all excited on the subject of his arrival; my mother, I say, was sitting by the fire, that bright, windy March afternoon, very timid and sad, and very doubtful of ever coming alive out of the trial that was before her, when, lifting her eyes as she dried them, to the window opposite, she saw a strange lady coming up the garden.

My mother had a sure foreboding at the second glance, that it was Miss Betsey. The setting sun was glowing on the strange lady, over the garden-fence, and she came walking up to the door with a fell rigidity of figure and composure of countenance that could have belonged to nobody else.

When she reached the house, she gave another proof of her identity. My father had often hinted that she seldom conducted herself like any ordinary Christian; and now, instead of ringing the bell, she came and looked in at that identical window, pressing the end of her nose against the glass to that extent, that my poor dear mother used to say it became perfectly flat and white in a moment.

She gave my mother such a turn, that I have always been convinced I am indebted to Miss Betsey for having been born on a Friday.

My mother had left her chair in her agitation, and gone behind it in the corner. Miss Betsey, looking round the room, slowly and inquiringly, began on the other side, and carried her eyes on, like a Saracen’s Head in a Dutch clock, until they reached my mother. Then she made a frown and a gesture to my mother, like one who was accustomed to be obeyed, to come and open the door. My mother went.

Frontispiece

Chapter 1

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

My mother was sitting by the fire, but poorly in health, and very low in spirits, looking at it through her tears, and desponding heavily about herself and the fatherless little stranger, who was already welcomed by some grosses of prophetic pins, in a drawer upstairs, to a world not at all excited on the subject of his arrival; my mother, I say, was sitting by the fire, that bright, windy March afternoon, very timid and sad, and very doubtful of ever coming alive out of the trial that was before her, when, lifting her eyes as she dried them, to the window opposite, she saw a strange lady coming up the garden.

My mother had a sure foreboding at the second glance, that it was Miss Betsey. The setting sun was glowing on the strange lady, over the garden-fence, and she came walking up to the door with a fell rigidity of figure and composure of countenance that could have belonged to nobody else.

When she reached the house, she gave another proof of her identity. My father had often hinted that she seldom conducted herself like any ordinary Christian; and now, instead of ringing the bell, she came and looked in at that identical window, pressing the end of her nose against the glass to that extent, that my poor dear mother used to say it became perfectly flat and white in a moment.

She gave my mother such a turn, that I have always been convinced I am indebted to Miss Betsey for having been born on a Friday.

My mother had left her chair in her agitation, and gone behind it in the corner. Miss Betsey, looking round the room, slowly and inquiringly, began on the other side, and carried her eyes on, like a Saracen’s Head in a Dutch clock, until they reached my mother. Then she made a frown and a gesture to my mother, like one who was accustomed to be obeyed, to come and open the door. My mother went.

Our Pew At Church

Chapter 2

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

Here is our pew in the church. What a high-backed pew! With a window near it, out of which our house can be seen, and IS seen many times during the morning’s service, by Peggotty, who likes to make herself as sure as she can that it’s not being robbed, or is not in flames. But though Peggotty’s eye wanders, she is much offended if mine does, and frowns to me, as I stand upon the seat, that I am to look at the clergyman. But I can’t always look at him—I know him without that white thing on, and I am afraid of his wondering why I stare so, and perhaps stopping the service to inquire—and what am I to do? It’s a dreadful thing to gape, but I must do something. I look at my mother, but she pretends not to see me. I look at a boy in the aisle, and he makes faces at me. I look at the sunlight coming in at the open door through the porch, and there I see a stray sheep—I don’t mean a sinner, but mutton—half making up his mind to come into the church. I feel that if I looked at him any longer, I might be tempted to say something out loud; and what would become of me then! I look up at the monumental tablets on the wall, and try to think of Mr. Bodgers late of this parish, and what the feelings of Mrs. Bodgers must have been, when affliction sore, long time Mr. Bodgers bore, and physicians were in vain. I wonder whether they called in Mr. Chillip, and he was in vain; and if so, how he likes to be reminded of it once a week. I look from Mr. Chillip, in his Sunday neckcloth, to the pulpit; and think what a good place it would be to play in, and what a castle it would make, with another boy coming up the stairs to attack it, and having the velvet cushion with the tassels thrown down on his head. In time my eyes gradually shut up; and, from seeming to hear the clergyman singing a drowsy song in the heat, I hear nothing, until I fall off the seat with a crash, and am taken out, more dead than alive, by Peggotty.

Commentary:

The initial illustration, chosen by artist and author collaboratively from among David's "earlier recollections" in Blunderstone, takes us outside the limitations of the child's retrospective first person point of view to reveal amongst a drowsing congregation an extremely alert Mr. Murdstone (left) studying the young widow in the Copperfield family pew in the village church. In its dramatizing complacent Anglicanism the plate by Phiz recalls an earlier satire of the Church of England by William Hogarth entitled The Sleeping Congregation (1736). The moment realized from the letterpress is this:

Here is our pew in the church. What a high-backed pew! With a window near it, out of which our house can be seen, and is seen many times during the morning's service, by Peggotty. . . . But though Peggotty's eye wanders, she is much offended if mine does, and frowns to me, as I stand upon the seat, that I am to look at the clergyman.

Significantly, the letterpress in which the mature David tries to recapture the child David's recollection of the Blunderstone church dwells upon authority figures — for example, Clara Peggotty, the presiding clergyman "singing a drowsy song", the local physician, Mr. Chillip, "in his Sunday neckcloth," and the narrator's mother), and a boy across the aisle — and utterly fails to mention the other observer of and in the scene, Mr. Murdstone. Whereas the diminutive David's gaze casually wanders to his mother beside him, that of the dark-haired, bewhiskered gentleman in the pew opposite is firmly fixed upon her. Steig notes that, given the ostensible subject of the illustration, a satire of complacent, country Anglicanism, Murdstone's presence so early in the narrative-pictorial sequence is not merely disquieting, but also quite unexpected.

The elaboration of all details in the illustration except Murdstone himself is perfectly consistent with Phiz's notion of paying homage to Hogarth's "The Sleeping Congregation," even though this is not the most vivid among David's "very earliest impressions". While David in the accompanying letterpress, gradually dozes off and falls off his seat with a crash, in the illustration he looks contemplatively at his mother, as if already considering the matter of his mother's re-marrying which he broaches subsequently to Peggotty. Although Phiz's David seems alert enough, his mother's eyes are either demurely downcast or momentarily closed, and a number of the congregation have fallen asleep, including the verger, the beadle (centre, left). While Murdstone disregards both his hymnal and Book of Common Prayer, the order of service belonging to the sleeping elderly woman in front of him takes an Irishman's rest on a tombstone, while a hymnal tumbles from the hands of a sleeping musician in the choir loft (upper centre), whereas in the Hogarthian original a pair of musicians' tricorn hats are falling from the sleepers' heads left of centre. The rector's assistant, although upright, has likewise fallen asleep and neglects his text. Among the figures of authority, only the pew-opener (right of centre in the foreground) and the minister at are attending to the service, while, right-of-centre, Clara Peggotty (as in the letterpress) looks out the window, preoccupied with the safety of the Rookery.

Although Phiz clearly keeps the focus on the congregation and the physical setting, he also invites us to read the very few words clearly readable: the "Bodgers" on the monument above Mrs. Copperfield's head, "Benefactors of the Church" in the sign below the choir, the Latin phrases (of which more shortly) on the tombstones in the foreground, and most significantly "MARR" from the Book of Common Prayer beside Murdstone, the book being open at the order of marriage. The "monumental tablets on the wall" are Phiz's point of departure for a detailed elaboration of the church's interior, beginning with a monumental crusader in the right foreground and culminating with the rococo cherubs blowing trumpets, a shield and shredded regimental flags at the apex of the gothic arch that determines the overall shape of the picture. Above David's mother, as in the letterpress, is the Bodgers monument, complemented by an Elizabethan statue of a nobleman above it, drawing the viewer's gaze towards the sleeping musicians and across the village minister and the dangling spider above him. Steig contends that the cobweb on the candelabrum to the left of the rector is a metaphor for the general drowsiness and inattentiveness of the congregation (who assume a prominence in Phiz's illustration largely lacking in the Hogarthian original), but the spider dangling from the cherub's trumpet immediately above the minister's neck is much more than a metaphor. At one level, it represents the possibility of an embarrassing moment, but at another it serves as a metaphor for the patient watcher at the bottom of the page. For Steig, "only the five little boys who look at a bird's nest with two eggs in it and mock the unconscious beadle lend any touch of life to the somnolent scene."

Strategically positioned near the empty font and the children, Murdstone is perhaps (as his keeping the prayer book open at the marriage service implies) already contemplating marrying the pretty widow. The overall effect may therefore be one of foreshadowing rather than simply metaphor. Steig proposes that the stolen bird's nest, a receptacle for two eggs, "may also symbolize the innocence of Mrs. Copperfield, soon to be violated by the cunning Murdstone, [so that] the spider and web assume sinister overtones as emblems of deceit and capture". Another subtly embedded symbolic image is that of Eve and the serpent in the Garden of Eden, barely discernible as a low-relief wood-engraving on the fascia of the pulpit, which again offers a metaphor for Murdstone's studied pursuit of the unprotected young woman. At the very bottom of the picture, as is consistent with the burial practices of small country churches prior to the Reformation, are two tombstones. However, these acquire symbolic significances through their Latin common enough inscriptions "Requiescat in Pace" (which the elderly parishioner just above this inscription is certainly doing) and "Resurgam," that is, "Rest in Peace" and "I shall rise again." Steig notes their underlying psychological import, suggestive as these inscriptions are of "David's fear of his father's grave and the 'raising of the dead' when Peggotty tells him 'You have got a pa'

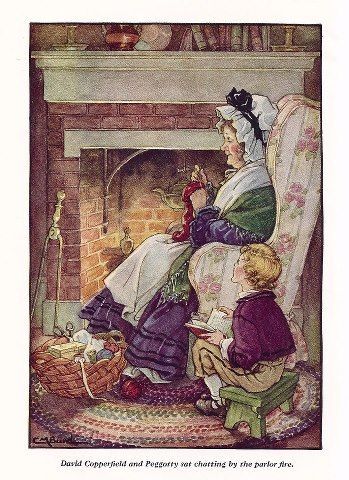

David as a child and Peggotty of an evening before the fire

Chapter 2

Fred Barnard

1872 Household Edition

Text Illustration:

Peggotty and I were sitting one night by the parlour fire, alone. I had been reading to Peggotty about crocodiles. I must have read very perspicuously, or the poor soul must have been deeply interested, for I remember she had a cloudy impression, after I had done, that they were a sort of vegetable. I was tired of reading, and dead sleepy; but having leave, as a high treat, to sit up until my mother came home from spending the evening at a neighbour’s, I would rather have died upon my post (of course) than have gone to bed. I had reached that stage of sleepiness when Peggotty seemed to swell and grow immensely large. I propped my eyelids open with my two forefingers, and looked perseveringly at her as she sat at work; at the little bit of wax-candle she kept for her thread—how old it looked, being so wrinkled in all directions!—at the little house with a thatched roof, where the yard-measure lived; at her work-box with a sliding lid, with a view of St. Paul’s Cathedral (with a pink dome) painted on the top; at the brass thimble on her finger; at herself, whom I thought lovely. I felt so sleepy, that I knew if I lost sight of anything for a moment, I was gone.

"That's not it?" said I, "that ship-looking thing?"

Chapter 3

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

Ham carrying me on his back and a small box of ours under his arm, and Peggotty carrying another small box of ours, we turned down lanes bestrewn with bits of chips and little hillocks of sand, and went past gas-works, rope-walks, boat-builders’ yards, shipwrights’ yards, ship-breakers’ yards, caulkers’ yards, riggers’ lofts, smiths’ forges, and a great litter of such places, until we came out upon the dull waste I had already seen at a distance; when Ham said,

‘Yon’s our house, Mas’r Davy!’

I looked in all directions, as far as I could stare over the wilderness, and away at the sea, and away at the river, but no house could I make out. There was a black barge, or some other kind of superannuated boat, not far off, high and dry on the ground, with an iron funnel sticking out of it for a chimney and smoking very cosily; but nothing else in the way of a habitation that was visible to me.

‘That’s not it?’ said I. ‘That ship-looking thing?’

‘That’s it, Mas’r Davy,’ returned Ham.

If it had been Aladdin’s palace, roc’s egg and all, I suppose I could not have been more charmed with the romantic idea of living in it. There was a delightful door cut in the side, and it was roofed in, and there were little windows in it; but the wonderful charm of it was, that it was a real boat which had no doubt been upon the water hundreds of times, and which had never been intended to be lived in, on dry land. That was the captivation of it to me. If it had ever been meant to be lived in, I might have thought it small, or inconvenient, or lonely; but never having been designed for any such use, it became a perfect abode.

I am hospitably received by Mr. Peggotty

Chapter 3

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

We were welcomed by a very civil woman in a white apron, whom I had seen curtseying at the door when I was on Ham’s back, about a quarter of a mile off. Likewise by a most beautiful little girl (or I thought her so) with a necklace of blue beads on, who wouldn’t let me kiss her when I offered to, but ran away and hid herself. By and by, when we had dined in a sumptuous manner off boiled dabs, melted butter, and potatoes, with a chop for me, a hairy man with a very good-natured face came home. As he called Peggotty ‘Lass’, and gave her a hearty smack on the cheek, I had no doubt, from the general propriety of her conduct, that he was her brother; and so he turned out—being presently introduced to me as Mr. Peggotty, the master of the house.

‘Glad to see you, sir,’ said Mr. Peggotty. ‘You’ll find us rough, sir, but you’ll find us ready.’

I thanked him, and replied that I was sure I should be happy in such a delightful place.

‘How’s your Ma, sir?’ said Mr. Peggotty. ‘Did you leave her pretty jolly?’

I gave Mr. Peggotty to understand that she was as jolly as I could wish, and that she desired her compliments—which was a polite fiction on my part.

‘I’m much obleeged to her, I’m sure,’ said Mr. Peggotty. ‘Well, sir, if you can make out here, fur a fortnut, ‘long wi’ her,’ nodding at his sister, ‘and Ham, and little Em’ly, we shall be proud of your company.’

Having done the honours of his house in this hospitable manner, Mr. Peggotty went out to wash himself in a kettleful of hot water, remarking that ‘cold would never get his muck off’. He soon returned, greatly improved in appearance; but so rubicund, that I couldn’t help thinking his face had this in common with the lobsters, crabs, and crawfish,—that it went into the hot water very black, and came out very red.

Commentary:

Steig notes that the underlying structure of the first and second illustrations is a gothic arch, the organizing principle behind the village church and the upside-down Peggotty boathouse. The focus of both plates on the figures, however, obscures the arches in the vertical and horizontal illustrations in the initial instalment. The plates may be taken as complementary in that David is an observer rather than an active participant. In the former, he studies key figures in the little community; in the latter, he studies the members of the "blended" Peggotty family organized around a surrogate father, Daniel Peggotty, as good-hearted and generous as Murdstone, who studies how to become David's stepfather in the former plate, is hard-hearted and controlling.

The figures in the illustration from left to right are Ham Peggotty, Dan'l Peggotty (centre left), David (seated), Clara Peggotty (identifiable by her elaborate bonnet from the previous illustration), Mrs. Gummidge, and Little Em'ly. The details in the background are consistent with the letterpress: a table (right), chest of drawers surmounted by a painted tea-tray and a bible (left), sundry pictures on the walls (subjects indistinguishable, a little mantel-shelf (rear), boxes, seats, and chairs, and "hooks in the beams of the ceiling". According to Hammerton the moment realized is this:

"I'm much obliged to her [David's mother], I'm sure," said Mr. Peggotty. "Well, sir, if you can make out here, for a fortnut, 'long wi' her," nodding to his sister, "and Ham, and little Em'ly, we shall be proud of your company."

However, the pot and kettle which Mr. Peggotty holds points towards the moment following this salutation:

Having done the honours of his house in this hospitable manner. Mr. Peggotty went out to wash himself in a kettleful of hot water, remarking that "cold would never get his muck off."

The companion plates for the May 1849 inaugural instalment establish David as an observer rather than an actor on the stage of his own life. His own respectable, middle-class home seems devoid of the kind of camaraderie and jollity that fills the unconventional dwelling of the "blended" Peggotty clan. David implicitly contrasts his dour stepfather-to-be with the companionable, working class surrogate father, Daniel Peggotty. Certainly the Peggottys will prove to be significant characters throughout the novel, giving the narrator- protagonist a proper sense of family life.

"Dead, Mr. Peggotty?" I hinted, after a respectful pause.

Chapter 3

Fred Barnard

1872 Household Edition

Text Illustration:

‘Mr. Peggotty!’ says I.

‘Sir,’ says he.

‘Did you give your son the name of Ham, because you lived in a sort of ark?’

Mr. Peggotty seemed to think it a deep idea, but answered:

‘No, sir. I never giv him no name.’

‘Who gave him that name, then?’ said I, putting question number two of the catechism to Mr. Peggotty.

‘Why, sir, his father giv it him,’ said Mr. Peggotty.

‘I thought you were his father!’

‘My brother Joe was his father,’ said Mr. Peggotty.

‘Dead, Mr. Peggotty?’ I hinted, after a respectful pause.

‘Drowndead,’ said Mr. Peggotty.

I was very much surprised that Mr. Peggotty was not Ham’s father, and began to wonder whether I was mistaken about his relationship to anybody else there. I was so curious to know, that I made up my mind to have it out with Mr. Peggotty.

‘Little Em’ly,’ I said, glancing at her. ‘She is your daughter, isn’t she, Mr. Peggotty?’

‘No, sir. My brother-in-law, Tom, was her father.’

I couldn’t help it. ‘—Dead, Mr. Peggotty?’ I hinted, after another respectful silence.

‘Drowndead,’ said Mr. Peggotty.

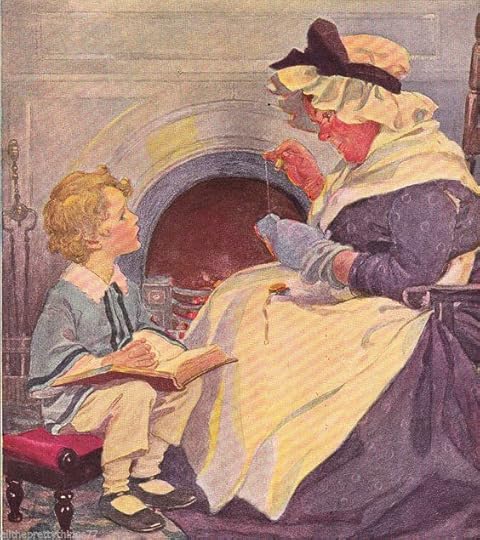

David and Little Em'ly

Chapter 3

Harold Copping

1924

Commentary:

The scene chosen to exemplify the happier aspects of the protagonist's childhood, "David and Little Em'ly," occurs on the Yarmouth sands when David goes to stay with Daniel Peggotty, whose family lives in a "kind of superannuated boat, . . . high and dry on the ground," which Phiz depicted as an upside down, even though the text does not so specify. Copping chose to be guided by the letterpress rather than by the original Phiz illustration. The moment realized occurs in installment one (chapter 3, "I Have a Change").

"Of all my books, I like this [David Copperfield ] the best. It will be easily believed that I am a fond parent to every child of my fancy, and that no one can ever love that family as dearly as I love them; but, like many fond parents, I have in my heart of hearts a favourite child, and his name is David Copperfield."

"So wrote Dickens in the preface to the original edition, and his own choice is shared by thousands of his readers. The book is in many respects the story of Dickens's own life up to a certain period, and the reality of it has stamped it as one of the first half-dozen novels in the language" [writes B. W. Matz in 1924].

Full as it is of incident, whimsicality, humour, pathos and adventure, the outstanding features of the book are its group of characters, all of whom become staunch friends wherever his books are read.

The four incidents following, deal with different periods of David's life, associated with Little Em'ly, Mr. Micawber, Uriah Heep, and many others — all old acquaintances. [In fact, as the depictions of David in the four illustrations make obvious, the artist's interests lie with David the child rather than with David the adult.

[Daniel] Peggotty and Little Em'ly

Chapter 3

Harold Copping

1924

The scene chosen to dramatise the life of the protagonist's second or adoptive family, "[Uncle Daniel] Peggotty and Little Em'ly," again occurs on the Yarmouth sands, upon the doorstep of the Peggottys' whimsical house. The moment depicted is based on David's recollections of his first meeting with Little Em'ly, which occurs in installment one (chapter 3, "I Have a Change")

Tristram wrote: "When reading Dickens, I often do it aloud when I have the chance"

In English or German? Just wondering.

In English or German? Just wondering.

Tristram wrote: "it is clear that the adult narrator must make sense of the memories of the narrator as a child. This must be very difficult stuff to write...."

Tristram wrote: "it is clear that the adult narrator must make sense of the memories of the narrator as a child. This must be very difficult stuff to write...."Which brings us to "Brooks of Sheffield". I wondered, as I read the exchange between Murdstone and his cronies, if Brooks of Sheffield was some pop culture reference that everyone would have recognized at the time. I did a bit of a search and it seems that Brooks of Sheffield was a Dickens original. Why Brooks? Why Sheffield? I guess it doesn't matter, and theoretically Murdstone came up with this code name on the spur of the moment, knowing about little pitchers and what big ears they can have.

Reading that scene was interesting, but imagine writing it! The adult narrator looking back on a conversation in his childhood that he did not understand at the time. What's more, Dickens doesn't add a wink or significant look to Murdstone's comment, nor does adult David feel the need to explain it in retrospect. Somehow, the story's conveyed in a way that the reader is in on the joke even though young David didn't understand. I think it's a brilliant bit of writing.

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "it is clear that the adult narrator must make sense of the memories of the narrator as a child. This must be very difficult stuff to write...."

Which brings us to "Brooks of Sheff..."

Mary Lou

Thank you for your research into Brooks and Sheffield. I often wonder what I am missing in a text simply because I am reading it in a different time period. Also, I had never heard the expression about little jugs with big ears that you used. That makes perfect sense to me as both a visual image and perhaps a verbal code in Murdstone’s conversation.

I agree that the interplay between David’s narration both as an adult and an adult looking back on his life is fascinating. What he distinctly remembers from his childhood is important as often embedded within his youthful recollections are bits of foreshadowing and teasing for his readers. Isn’t this a great novel?

The image beside your name looks especially familiar to me this week :-)

Which brings us to "Brooks of Sheff..."

Mary Lou

Thank you for your research into Brooks and Sheffield. I often wonder what I am missing in a text simply because I am reading it in a different time period. Also, I had never heard the expression about little jugs with big ears that you used. That makes perfect sense to me as both a visual image and perhaps a verbal code in Murdstone’s conversation.

I agree that the interplay between David’s narration both as an adult and an adult looking back on his life is fascinating. What he distinctly remembers from his childhood is important as often embedded within his youthful recollections are bits of foreshadowing and teasing for his readers. Isn’t this a great novel?

The image beside your name looks especially familiar to me this week :-)

Kim wrote: "Tristram wrote: "When reading Dickens, I often do it aloud when I have the chance"

In English or German? Just wondering."

In English. Reading Dickens in German is only half the fun because a lot of the original gets lost. Apart from that, English is the finest language I know, with German close at its heels, of course.

In English or German? Just wondering."

In English. Reading Dickens in German is only half the fun because a lot of the original gets lost. Apart from that, English is the finest language I know, with German close at its heels, of course.

Mary Lou, I think I can account for the "Sheffield" but not for the "Brooks". When Mr. Quinion makes his incautious remark about Mrs. Copperfield, Murdstone warns him to watch his tongue because, as he says, someone here is sharper than he seems, which obviously refers to David. Knives are also sharp, and Sheffield knives were, and maybe, still are renowned for their quality. In Germany, the town Solingen is famous for its knives, by the way.

As to "Brooks", I don't know, but maybe - but this is far-fetched, it is because Mr. Murdstone does not really brook David?

As to "Brooks", I don't know, but maybe - but this is far-fetched, it is because Mr. Murdstone does not really brook David?

Thanks for your illustrations, Kim. I am shocked at the plethora of idealized depictions of fat-cheeked, golden-locked boys the artists come up with. Likewise, Sol Eytinge's Little Em'ly looks as though she had been in the water for too long a time ... sorry, if this is too nasty, but it's my nature ;-)

Tristram wrote: "Thanks for your illustrations, Kim. I am shocked at the plethora of idealized depictions of fat-cheeked, golden-locked boys the artists come up with. Likewise, Sol Eytinge's Little Em'ly looks as t..."

I agree (for once). :-)

I agree (for once). :-)

Tristram wrote: "Mary Lou, I think I can account for the "Sheffield" but not for the "Brooks". When Mr. Quinion makes his incautious remark about Mrs. Copperfield, Murdstone warns him to watch his tongue because, a..."

I looked up Brooks of Sheffield once and found this explanation which I find a bit unbelievable but I've never looked further into it:

Brooks of Sheffield:

In Charles Dicken's "David Copperfield", Mr. Murdstone refers to David as "Brooks of Sheffield." This is a play on words using the verb form of "Brook" meaning "to endure" and David's home town, Sheffield. Mr. Murdstone is interested in David's mother, but sees him as something to be endured, or put up with.

I've never known of the word brooks meaning to endure and I don't remember the town David lives in as Sheffield, but as I said I didn't look.

I looked up Brooks of Sheffield once and found this explanation which I find a bit unbelievable but I've never looked further into it:

Brooks of Sheffield:

In Charles Dicken's "David Copperfield", Mr. Murdstone refers to David as "Brooks of Sheffield." This is a play on words using the verb form of "Brook" meaning "to endure" and David's home town, Sheffield. Mr. Murdstone is interested in David's mother, but sees him as something to be endured, or put up with.

I've never known of the word brooks meaning to endure and I don't remember the town David lives in as Sheffield, but as I said I didn't look.

Then there is this, whether true or not I don't know:

The gift that led Dickens to give up his treasured copy of David Copperfield:

The superstitious nature of Britain's greatest writer has come to light thanks to the sale of an inscribed first edition of Charles Dickens' favourite novel with its own intriguing backstory.

The auction of the author's personal copy of David Copperfield – his most autobiographical novel and his "favourite child" – has provided new insight into why Dickens gifted the book to a Sheffield tool manufacturer to dispel a curse.

It was first published in book form in 1850 to great acclaim, but when it was read by the owner of a Sheffield company named William Brookes and Sons, he was shocked to find its eponymous main character being ridiculed with an insulting nickname – "Brooks of Sheffield" – similar to his firm.

He contacted the author about the inadvertent slur and correspondence ensued, with Dickens telling the owner that the name was "one of those remarkable coincidences". He added: "I had no idea that I was taking a liberty with any existing firm, and why I added Sheffield to Brooks (of all the towns in England) I have no... knowledge. It came to my head as I wrote."

The factory owner subsequently presented him with a cutlery case in 1851. But the superstition that if a knife is received as a present the relationship of giver and recipient will be severed led Dickens to send his treasured edition in return. The volume is believed to have been with the Brookes family ever since.

While the letter from Dickens is in Yale University archives, scholars had no idea the actual volume, inscribed to "Brookes of Sheffield", had survived, or that it is accompanied by another autographed letter from Dickens apologising for its delay.

Dickens was so popular in his day that his books were published in great quantities, meaning an ordinary first edition today might be worth only £1,000. But the author's well-thumbed volume originally from his own shelves, inscribed and accompanied by a letter from Dickens, could be worth 50 times as much when it is auctioned at Christie's in London on 13 June.

David Copperfield was his most personal novel. Using material from his abandoned autobiography, it drew on his own life, including his father, the inspiration for Micawber, one of his greatest comic characters.

Whether a friendship ensued between the author and the industrialist is unknown, but the gift implies it. Dickens once wrote: "Like many fond parents, I have in my heart of hearts a favourite child. And his name is David Copperfield."

The gift that led Dickens to give up his treasured copy of David Copperfield:

The superstitious nature of Britain's greatest writer has come to light thanks to the sale of an inscribed first edition of Charles Dickens' favourite novel with its own intriguing backstory.

The auction of the author's personal copy of David Copperfield – his most autobiographical novel and his "favourite child" – has provided new insight into why Dickens gifted the book to a Sheffield tool manufacturer to dispel a curse.

It was first published in book form in 1850 to great acclaim, but when it was read by the owner of a Sheffield company named William Brookes and Sons, he was shocked to find its eponymous main character being ridiculed with an insulting nickname – "Brooks of Sheffield" – similar to his firm.

He contacted the author about the inadvertent slur and correspondence ensued, with Dickens telling the owner that the name was "one of those remarkable coincidences". He added: "I had no idea that I was taking a liberty with any existing firm, and why I added Sheffield to Brooks (of all the towns in England) I have no... knowledge. It came to my head as I wrote."

The factory owner subsequently presented him with a cutlery case in 1851. But the superstition that if a knife is received as a present the relationship of giver and recipient will be severed led Dickens to send his treasured edition in return. The volume is believed to have been with the Brookes family ever since.

While the letter from Dickens is in Yale University archives, scholars had no idea the actual volume, inscribed to "Brookes of Sheffield", had survived, or that it is accompanied by another autographed letter from Dickens apologising for its delay.