Litwit Lounge discussion

The Classics

>

Jean's Charles Dickens Challenge

One intriguing thought, relating now to the end, is (view spoiler)

One intriguing thought, relating now to the end, is (view spoiler) It's quite possible that this was one of the threads Dickens didn't pursue, or bring out at a dramatic moment. His diaries and letters to John Forster may mention something. I'll keep my eyes open!

And another interesting thought, at the end of chapter 10, when (view spoiler) he wants to tell him his true name and family, but Dr Manette shrugs it aside. Why? Dr Manette seems privy to many secrets, and I don't feel they are all fantasies in his mind.

And another interesting thought, at the end of chapter 10, when (view spoiler) he wants to tell him his true name and family, but Dr Manette shrugs it aside. Why? Dr Manette seems privy to many secrets, and I don't feel they are all fantasies in his mind.

Charles Darnay and Sydney Carton:

Charles Darnay and Sydney Carton:(a working post, edited now and then, and under spoilers)

Known facts from the text, assuming no unreliable narrators

(view spoiler)

Concerning whether the doppelgängers were more than just doppelgängers I agree with John, and with all such theories think it was deliberately left open-ended for precisely the reason John quoted.

Concerning whether the doppelgängers were more than just doppelgängers I agree with John, and with all such theories think it was deliberately left open-ended for precisely the reason John quoted. Just sometimes this strategy has let him down, and there are inconsistencies in some of his novels which, if we want to nitpick, we can find. The academic John Sutherland is very good at spotting that sort of thing in Dickens and other writers, and has written three or four book of literary conundrums, three of which I've reviewed on my shelves if you're interested, Jenny: link here

It doesn't stop us speculating though, just as we might analyse someone's character in terms of whether they would really do such a thing with their personality etc., even though we know they are fictitious! The other point is that he seems to have finetuned a convenient strategy, for those writing serial fiction and not able to go back and edit, by skilfully weaving ambiguity into the very plot itself.

Ironically, my edition has no illustrations (it's "clear print" which I'm finding hard to read, hence my slowness) yet this novel seems to have had more illustrators over time than any other! Perhaps because it is so very popular - and then perhaps because it was originally weekly with some, then monthly with others, and then as a book - with different illustrators coming along all the time, even now.

Ironically, my edition has no illustrations (it's "clear print" which I'm finding hard to read, hence my slowness) yet this novel seems to have had more illustrators over time than any other! Perhaps because it is so very popular - and then perhaps because it was originally weekly with some, then monthly with others, and then as a book - with different illustrators coming along all the time, even now.

I like this one by Fred Barnard, from chapter 9 in the second book - this is an event I forget happens every single time I read this book!

I like this one by Fred Barnard, from chapter 9 in the second book - this is an event I forget happens every single time I read this book!(view spoiler)

And after all that, the chapter ends "the city ran into death according to rule ... all things ran their course."

Talk about doom-laden!

And the fountain itself is highly symbolic:

And the fountain itself is highly symbolic:"the carriage dashed through streets and swept round corners, with women screaming before it, and men clutching each other and clutching children out of its way. At last, swooping at a street corner by a fountain, one of its wheels came to a sickening little jolt"

Usually a fountain is seen representing a life force, a symbol of fecundity, and also associated with the passing of time, with fate and death. Look how Harry Furniss illustrated it:

(view spoiler)

Fanciful, but I like it! I'm sure Dickens placing this catastrophe right next to the fountain was quite deliberate.

Dickens was always so explicit and detailed with his instructions to Phiz about how he wanted his stories illustrated, but some other artists of the time (or shortly after) are well worth looking at!

I mentioned the significant initials earlier, but apparently originally Sydney Carton was intended to be Dick Carton, ie Dickens's initials reversed - just as Charles Darnay is obviously a name mirrored on the author's own name. Perhaps he felt it would have been too obvious for the two young men to have the initials D.C. and C.D: both looking alike but reversed in character.

I mentioned the significant initials earlier, but apparently originally Sydney Carton was intended to be Dick Carton, ie Dickens's initials reversed - just as Charles Darnay is obviously a name mirrored on the author's own name. Perhaps he felt it would have been too obvious for the two young men to have the initials D.C. and C.D: both looking alike but reversed in character.Just as it seems a bit unnecessary for Sydney Carton to view (view spoiler) Dickens identified with him and saw himself as a victim of circumstances. A reader can see the parallels - but may also view these as copouts. (Well, this one does anyway!)

This time through them all I'm noticing the theatricality of them all a lot more. The main difference for me is in the low level of humour - although it is there - he puts in little comments quite slyly :)

This time through them all I'm noticing the theatricality of them all a lot more. The main difference for me is in the low level of humour - although it is there - he puts in little comments quite slyly :)There's quite a lot of dark humour I'm finding. The Crunchers, for instance. Take this early illustration by John McLenan:

And many of the descriptions are ghastly in a sardonic way. The horror of the (view spoiler) is truly macabre. Almost like Poe!

Perhaps some find the odd bits of flippancy when describing a character a little out of place.

I'm aware of a lot more foreshadowing - almost every chapter seems to end with portentous words, and references to what is to come. I'm not sure whether this is because Dickens had the story well plotted out in his mind (which was still a fairly new way of working for him) or whether it was because he knew his audience already did, because of the historical setting. It's further complicated, of course, by the fact that some of us are coming to it knowing the details of Dickens's story very well too!

I'm aware of a lot more foreshadowing - almost every chapter seems to end with portentous words, and references to what is to come. I'm not sure whether this is because Dickens had the story well plotted out in his mind (which was still a fairly new way of working for him) or whether it was because he knew his audience already did, because of the historical setting. It's further complicated, of course, by the fact that some of us are coming to it knowing the details of Dickens's story very well too!I actually think the plot construction in this one is particularly good! Though the language he uses tends to be a bit too convoluted - I like him creating an air of mystery but not so much that I have to reread parts to understand the implications. I'm still not thinking it's one of his "greats". Of the two historical ones I prefer Barnaby Rudge so far.

I'm currently thinking how very different the humour is in this book. Lots of the savage cynicism, also the grotesquerie, (That illustration seems almost modern to me!) not so much of the laugh out loud ridiculous absurdity (which I miss!) and some newish sort of drollery - the large-chinned king and his fair-faced wife. Will try to find examples - those seem to be 4 distinct types to me.

I'm currently thinking how very different the humour is in this book. Lots of the savage cynicism, also the grotesquerie, (That illustration seems almost modern to me!) not so much of the laugh out loud ridiculous absurdity (which I miss!) and some newish sort of drollery - the large-chinned king and his fair-faced wife. Will try to find examples - those seem to be 4 distinct types to me. I had thought this a dour and cheerless novel, but perhaps it's just that he's branching out into different types of humour.

Jerry and Mrs. Cruncher are clearly grotesque characters, put in for light relief, though (view spoiler). But then thinking of Punch and Judy shows, perhaps this is the sort of slapstick humour we have there too.

Surely we're also supposed to laugh wryly at young Jerry's admiration of his father, as it is taken to such an extreme point. (view spoiler)

Any scenes with Miss Pross in are always really funny too. We need some of this comic relief to contrast with the hairraising parts!

Book 2 chapter 22 - one of the parts which made the hair stand on my head ...

Book 2 chapter 22 - one of the parts which made the hair stand on my head ..."Instantly Madame Defarge's knife was in her girdle; the drum was beating in the streets, as if it and a drummer had flown together by magic; and The Vengeance, uttering terrific shrieks, and flinging her arms about her head like all the forty Furies at once, was tearing from house to house, rousing the women.

The men were terrible, in the bloody-minded anger with which they looked from windows, caught up what arms they had, and came pouring down into the streets; but, the women were a sight to chill the boldest. From such household occupations as their bare poverty yielded, from their children, from their aged and their sick crouching on the bare ground famished and naked, they ran out with streaming hair, urging one another, and themselves, to madness with the wildest cries and actions. Villain Foulon taken, my sister! Old Foulon taken, my mother! Miscreant Foulon taken, my daughter! Then, a score of others ran into the midst of these, beating their breasts, tearing their hair, and screaming, Foulon alive! Foulon who told the starving people they might eat grass! Foulon who told my old father that he might eat grass, when I had no bread to give him! Foulon who told my baby it might suck grass, when these breasts were dry with want! O mother of God, this Foulon! O Heaven our suffering! Hear me, my dead baby and my withered father: I swear on my knees, on these stones, to avenge you on Foulon! Husbands, and brothers, and young men, Give us the blood of Foulon, Give us the head of Foulon, Give us the heart of Foulon, Give us the body and soul of Foulon, Rend Foulon to pieces, and dig him into the ground, that grass may grow from him! With these cries, numbers of the women, lashed into blind frenzy, whirled about, striking and tearing at their own friends until they dropped into a passionate swoon, and were only saved by the men belonging to them from being trampled under foot."

This is terrifically theatrical writing - reminds me of parts of Barnaby Rudge

This too, which I'll put under a spoiler (view spoiler)

This too, which I'll put under a spoiler (view spoiler)Incredibly passionate writing. And this illustration by Fred Barnard is so powerful, I think:

Yet we haven't even got to any mention of (view spoiler)!

When I reflect, I think this book is too short, but he certainly cranks up the tension within it. I'm not sure what it is about much of the writing which seems so compressed and convoluted.

I think this is possibly the first time where I think some other illustrators have done the story and characters as much (or more, in some cases) justice as Phiz - at least for the very dramatic parts - whilst still incorporating that ghoulish and grotesque humour. Look at this by Harry Furniss, of the same scene:

I think this is possibly the first time where I think some other illustrators have done the story and characters as much (or more, in some cases) justice as Phiz - at least for the very dramatic parts - whilst still incorporating that ghoulish and grotesque humour. Look at this by Harry Furniss, of the same scene:

And how about Mme Defarge - or perhaps her friend "The Vengeance" - here, by Sol Eytinge Jr:

Dickens is making my hair stand on end at the beginning of book 3:

Dickens is making my hair stand on end at the beginning of book 3:"Above all, one hideous figure grew as familiar as if it had been before the general gaze from the foundations of the world—the figure of the sharp female called La Guillotine.

It was the popular theme for jests; it was the best cure for headache, it infallibly prevented the hair from turning grey, it imparted a peculiar delicacy to the complexion, it was the National Razor which shaved close: who kissed La Guillotine, looked through the little window and sneezed into the sack. It was the sign of the regeneration of the human race. It superseded the Cross. Models of it were worn on breasts from which the Cross was discarded, and it was bowed down to and believed in where the Cross was denied.

It sheared off heads so many, that it, and the ground it most polluted, were a rotten red. It was taken to pieces, like a toy-puzzle for a young Devil, and was put together again when the occasion wanted it. It hushed the eloquent, struck down the powerful, abolished the beautiful and good. Twenty-two friends of high public mark, twenty-one living and one dead, it had lopped the heads off, in one morning, in as many minutes."

Words to make you shudder, indeed, and strike fear into you however cosily you sit reading. And then a little earlier I loved this droll irony about the imprisoned aristocrats:

"So strangely clouded were these refinements by the prison manners and gloom, so spectral did they become in the inappropriate squalor and misery through which they were seen, that (view spoiler) seemed to stand in a company of the dead. Ghosts all! The ghost of beauty, the ghost of stateliness, the ghost of elegance, the ghost of pride, the ghost of frivolity, the ghost of wit, the ghost of youth, the ghost of age, all waiting their dismissal from the desolate shore, all turning on him eyes that were changed by the death they had died in coming there."

I'm getting to really like the illustrations by Fred Barnard, and think I might prefer them for this novel as I said before. The seriousness is heightened, and he focus in close for much of the time:

I'm getting to really like the illustrations by Fred Barnard, and think I might prefer them for this novel as I said before. The seriousness is heightened, and he focus in close for much of the time:

This is from the trial (a kangaroo court!) of (view spoiler). But look at the attiudes of those (pre) judging, who have folded arms to mirror their closed minds. Look at the malevolence of the officer, the swarthy character at the desk. They are implacable and unlikely to listen to anything he might say in his defence.

The tension has been cranked up notch by notch, and realisation has been dawning on the accused slightly after the reader - superby crafted. He has protested earlier:

"Emigrant, my friends! Do you not see me here, in France, of my own will?"

"Friends, you deceive yourselves, or you are deceived. I am not a traitor."

But we know the game is up for him when the officer says:

"We have new laws, Evremonde, and new offences, since you were here." He said it with a hard smile, and went on writing."

And this one from chapter 2 "The Grindstone" looks like a vision of Hell:

And this one from chapter 2 "The Grindstone" looks like a vision of Hell:

Dr. Manette has said, "I have a charmed life in this city" but for how long? We see descriptions of mob mentalitity - also in the courtroom, with wild swings from one side to the other. Horrific images of "horrible and cruel faces" the "wildest savages in their most barbarous disguise" ... " hideous ... all bloody and sweaty" ... "howling, and all staring and glaring with beastly excitement."

"Such awful workers, and such awful work."

With chapter 5 "The Carmagnole" I had to leave this for a while and take a breather! Such a horrific wardance ... these descriptions are of tribal warriors under the influence not really of any stimulants (except drink) but their own extreme passions and years of poverty and oppression:

With chapter 5 "The Carmagnole" I had to leave this for a while and take a breather! Such a horrific wardance ... these descriptions are of tribal warriors under the influence not really of any stimulants (except drink) but their own extreme passions and years of poverty and oppression:

" ... presently she heard a troubled movement and a shouting coming along, which filled her with fear ...a throng of people came pouring round the corner by the prison wall. There could not be fewer than five hundred people, and they were dancing like five thousand demons. There was no other music than their own singing. They danced to the popular Revolution song, keeping a ferocious time that was like a gnashing of teeth in unison. Men and women danced together, women danced together, men danced together, as hazard had brought them together. At first, they were a mere storm of coarse red caps and coarse woollen rags; but, as they filled the place, and stopped to dance about Lucie, some ghastly apparition of a dance-figure gone raving mad arose among them. They advanced, retreated, struck at one another's hands, clutched at one another's heads, spun round alone, caught one another and spun round in pairs, until many of them dropped. While those were down, the rest linked hand in hand, and all spun round together: then the ring broke, and in separate rings of two and four they turned and turned until they all stopped at once, began again, struck, clutched, and tore, and then reversed the spin, and all spun round another way. Suddenly they stopped again, paused, struck out the time afresh, formed into lines the width of the public way, and, with their heads low down and their hands high up, swooped screaming off. No fight could have been half so terrible as this dance. It was so emphatically a fallen sport — a something, once innocent, delivered over to all devilry — a healthy pastime changed into a means of angering the blood, bewildering the senses, and steeling the heart ...

This was the Carmagnole. As it passed, leaving Lucie frightened and bewildered in the doorway of the wood-sawyer's house, the feathery snow fell as quietly and lay as white and soft, as if it had never been."

These are normal people, not devils or monsters, but they are suddenly turned into maniacal murderers during the course of the Revolution. All their resentment against the aristocracy, the social envy, their understandable disgust with social and political injustice, resulted in this hysteria and paranoia. Terrifying. Horrifying.

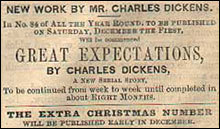

Great Expectations

Great Expectations

The original serialisation was weekly, in "All the Year Round" in nine monthly sections between December 1860 and August 1861. Here they are, with the later chapter equivalents:

chapters 1–8

1, 8, 15, 22, 29 December 1860

chapters 9–15

5, 12, 19, 26 January 1861

chapters 16–21

2, 9, 23 February 1861

chapters 22–29

2, 9, 16, 23, 30 March 1861

chapters 30–37

6, 13, 20, 27 April 1861

chapters 38–42

4, 11, 18, 25 May 1861

chapters 43–52

1, 8 15, 22, 29 June 1861

chapters 53–57

6, 13, 20, 27 July 1861

chapters 58–59

3 August 1861

It was also serialised in the US and on the continent. Then Dickens's publishers, Chapman and Hall, published the first edition in book form in three volumes in 1861, with five subsequent reprints, and a one-volume edition in 1862.

Great Expectations feels very autobiographical, which it is, though fictionalised, and not so much as David Copperfield. In fact Charles Dickens made a point of rereading David Copperfield before beginning work on Great Expectations, just in case he unintentionally repeated anything!

Great Expectations feels very autobiographical, which it is, though fictionalised, and not so much as David Copperfield. In fact Charles Dickens made a point of rereading David Copperfield before beginning work on Great Expectations, just in case he unintentionally repeated anything! Some people think it's his darkest work, but it is full of his own brand of Dickensian humour. Dickens himself wrote to his mentor and biographer John Forster,

"You will not have to complain of the want of humour as in the Tale of Two Cities,"

and Forster later agreed,

"Dickens's humour, not less than his creative power, was at its best in this book."

Victorian readers loved it, and it remains one of Dickens's most popular works today. Many consider Great Expectations to be Dickens's masterpiece; the novel with the most dramatic plot, characterisation and style.

I've just reread the first two chapters and been alternately chortling and horrified (and occasionally together!) already. People often ask which is the best one to start with. I continue to steer people away from the shorter ones they are tempted by (A Tale of Two Cities and Hard Times) as I feel that these are both, in different ways, better tackled later. But David Copperfield is a great one to start with, and I think Great Expectations probably is too, if this charismatic, easy-flowing writing continues.

A NOTE ABOUT THE ENDING:

A NOTE ABOUT THE ENDING:Charles Dickens seemed to leave it deliberately vague, having changed it after a friend said it was too sad. Various dramatisations have put their own interpretations on it ... I seem to remember the David Lean film quoted the actual text, which was quite a clever way of getting round it. But we'll get to that in due course. Meanwhile just a couple of chapters this week :)

Thinking of what was actually going on in Charles Dickens's life at the time he started this:

Thinking of what was actually going on in Charles Dickens's life at the time he started this:Dickens was 48 to 49 years of age. His domestic life was in tatters, as it had rapidly gone downhill in the late 1850s, and he had now separated from his wife, Catherine. He was having a secret affair with an actress, the much younger Ellen Ternan. (Some critics think that she is the basis for the character of Estelle, but more of that later.)

During the writing of Great Expectations, Dickens went on tour, reading and acting out parts of his immensely popular novels. In March and April 1861 alone, he gave six public readings. More like performances, they were very successful in every way, but it took a terrible toll on his health.

Great Expectations seems to come after quite a gap between actual novels. Charles Dickens had published A Tale of Two Cities in 1859, written the collection of papers The Uncommercial Traveller in 1860, and was wondering what big project to embark on next. He had the idea of Pip and the convict in his mind, and wrote to John Forster,

Great Expectations seems to come after quite a gap between actual novels. Charles Dickens had published A Tale of Two Cities in 1859, written the collection of papers The Uncommercial Traveller in 1860, and was wondering what big project to embark on next. He had the idea of Pip and the convict in his mind, and wrote to John Forster,"For a little piece I have been writing—or am writing; for I hope to finish it to-day—such a very fine, new, and grotesque idea has opened upon me, that I begin to doubt whether I had not better cancel the little paper, and reserve the notion for a new book. You shall judge as soon as I get it printed. But it so opens out before me that I can see the whole of a serial revolving on it, in a most singular and comic manner."

And a few days later, after much discussion about money,

"The book will be written in the first person throughout, and during these first three weekly numbers you will find the hero to be a boy-child, like David. You will not have to complain of the want of humour as in the Tale of Two Cities. I have made the opening, I hope, in its general effect exceedingly droll. I have put a child and a good-natured foolish man, in relations that seem to me very funny. Of course I have got in the pivot on which the story will turn too—and which indeed, as you remember, was the grotesque tragi-comic conception that first encouraged me. To be quite sure I had fallen into no unconscious repetitions, I read David Copperfield again the other day, and was affected by it to a degree you would hardly believe."

Charles Dickens knew the locations he describes very well:

Charles Dickens knew the locations he describes very well:Jo Gargery's forge is located at Chalk village in Kent, and he used the forge where he and Catherine stayed on their honeymoon in 1836 as a basis.

The churchyard where Pip's family is buried, and he meets the convict (view spoiler) is Cooling churchyard. He describes Cooling Castle ruins and the desolate Church, lying out among the marshes seven miles from Gadshill

"My first most vivid and broad impression . . . on a memorable raw afternoon towards evening . . . was . . . that this bleak place, overgrown with nettles, was the churchyard, and that the dark flat wilderness beyond the churchyard, intersected with dykes and mounds and gates, with scattered cattle feeding on it, was the marshes; and that the low leaden line beyond, was the river; and that the distant savage lair from which the wind was rushing, was the sea. . . . On the edge of the river . . . only two black things in all the prospect seemed to be standing upright . . . one, the beacon by which the sailors steered, like an unhooped cask upon a pole, an ugly thing when you were near it; the other, a gibbet with some chains hanging to it which had once held a pirate."

Dickens lived in Chatham as a child, between the ages of 5 and 11, and this is only a couple of miles away from Cooling. Although Dickens had been born in Portsmouth, his father moved the family to Chatham, near where the hulks were moored. When any convicts escaped, Chatham would have been one of the towns they fled to. Dickens explored this landscape thoroughly and would have known it well.

When older, and a successful writer, he bought a house he had admired as a child, "Gad's Hill". It is located between Chatham and Gravesend. It is at Gads Hill where he started writing Great Expectations in October, 1860.

The marshland around there is still quite bleak.

He also knew Rochester well. "Satis House", (Miss Havisham's house, which we haven't quite come to) was based on "Restoration House" in Rochester. Charles II stayed there on his return to England in 1660, restoring the English monarchy after Oliver Cromwell.

He also knew Rochester well. "Satis House", (Miss Havisham's house, which we haven't quite come to) was based on "Restoration House" in Rochester. Charles II stayed there on his return to England in 1660, restoring the English monarchy after Oliver Cromwell.I'm finding this book seems to encapsulate the best of Dickens right from the start. We have the horror allied with the humour. And making the viewpoint character a young boy, as in David Copperfield, is something he does so very well, drawing the reader in to experience what the young boy apparently is doing. There's a lot of menace both from the environment and the convict he meets, and yet he also has a similar fear of his sister, the elder by 20 years. But the writing is so droll - his confusion as to what exactly was meant by being "brought up by hand".

Thus is definitely grabbing me; he's on to a winner here! I've been looking into the illustrations and am amazed how many there are. But by now he had dispensed with Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz)'s services. Such a shame as he was the one we all associate with Dickens's novels. Charles Dickens seemed to fall out with everyone in the end ... except I guess John Forster.

Thus is definitely grabbing me; he's on to a winner here! I've been looking into the illustrations and am amazed how many there are. But by now he had dispensed with Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz)'s services. Such a shame as he was the one we all associate with Dickens's novels. Charles Dickens seemed to fall out with everyone in the end ... except I guess John Forster. I must look to see if they remained friends and it was just a professional disagreement. After all, Charles Dickens may have felt that with the seriousness of these later novels, the caricatured style of "Phiz" was no longer appropriate. But I can already think of many characters who are ripe for such treatment, starting with Pip's harridan of a sister! Dickens had an eye to be thought of as a "great" serious literary novelist, and perhaps by now this urge had become so strong that he pared away anything which he thought might hold him back.

Joe was flaxen-haired! That was a real surprise to me. Fair hair and blue eyes. I must have seen too many dramatisations which made him dark. So we have the darkness of the sister and a light, fair brother, which probably how Pip sees them. And I also noticed this time that the convict (view spoiler), a very neat bit of subtextual foreshadowing, if I can put it that way! It seems to indicate his nature.

Joe was flaxen-haired! That was a real surprise to me. Fair hair and blue eyes. I must have seen too many dramatisations which made him dark. So we have the darkness of the sister and a light, fair brother, which probably how Pip sees them. And I also noticed this time that the convict (view spoiler), a very neat bit of subtextual foreshadowing, if I can put it that way! It seems to indicate his nature.

ILLUSTRATIONS:

ILLUSTRATIONS:Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Pictures Printed From the Original Wood Blocks has Thirty Illustrations by F.A. Fraser (from the Household Edition, says The Victorian Web). Not very good, although some darker ones are atmospheric. There are also 6 illustrations, which are lifeless, by Warwick Goble in a small World's Classics (according to John F.)

On Kindle versions, one has a single, lovely, one by Marcus Stone, called "With Estella after all".

The serialisation and the first book edition had no illustrations. David Perdue's Charles Dickens Page shows 21 etchings by FW Pailthorpe for the Robson & Kerslake 1885 edition. Rather good, like Browne, but a bit Pickwickian for a later Dickens.

I'm thinking of all the dramatisations there have been of Great Expectations, and short though it is, (I think it even misses Orlick as a character out completely !) I still like David Lean's film about the best!

I'm thinking of all the dramatisations there have been of Great Expectations, and short though it is, (I think it even misses Orlick as a character out completely !) I still like David Lean's film about the best!Great Expectations, out of all his novels, and David Copperfield are both great to start with, I think. But it's Great Expectations which has a wonderful mystery story at its core. The other similar-feeling one I think is Bleak House. They both have gothic elements too, but Great Expectations is less fiendishly complex. Dickens's writing can take some getting used to!

What I would say to any new readers of Dickens though, is PLEASE don't read any blurbs, or watch any films etc of it, before you start if you read Great Expectations. There are a couple of really big twists which happen a long way through the novel, and the story is so well known that sometimes people reveal something without thinking.

He's so funny in these early chapters!

He's so funny in these early chapters!I've heard it said (by readers on this site) that people don't think Dickens is funny, and I always assumed it's only the later, darker books they've read, such as Great Expectations. But then again, even this one is jam-packed with little asides and sarcastic comments. Here are some from the first 4 chapters:

(view spoiler) is just so ghoulish it is surely also very blackly funny - because it is seen from a child's terrified point of view. When Pip is literally (view spoiler) it is a very lightly amused touch by Dickens - it's still funny, but there's even more of the very morbid humour Dickens likes so much in these early scenes.

Even the "five little stone lozenges" is a light-hearted reference to something really full of pathos and tragedy. A common enough event then, sadly.

"The Tickler" is another example - a gentle name for something which was capable of inflicting a great deal of pain!

"Having at that time to find out for myself what the expression meant, and knowing her to have a hard and heavy hand, and to be much in the habit of laying it upon her husband as well as upon me, I supposed that Joe Gargery and I were both brought up by hand.

She was not a good-looking woman, my sister; and I had a general impression that she must have made Joe Gargery marry her by hand.”

What a great sarcastic double-edged phrase "brought up by hand" is. And it serves as a catch-phrase too, to make sure his readers did not forget the characters whilst waiting for him to write the next issue. I always think of this one whenever I think of Pip's termagent of a sister, full of bitterness and self-inflicted martyrdom, knocking Joe's head against the wall or banging Pip's head like a tambourine with her thimble!

"My sister... had such a prevailing redness of skin that I sometimes used to wonder whether it was possible she washed herself with a nutmeg-grater instead of soap."

And this,

"Even when I was taken to have a new suit of clothes, the tailor had orders to make them like a kind of Reformatory, and on no account to let me have the free use of my limbs.”

The image of Pip being trussed up in clothes far too tight to be comfortable - and always poked and pushed into a corner, between all the adults' elbows and arms :)

Joe feeling so sorry for him, that he tried to make everything better by giving him more and more ladles of gravy - about half a pint as I remember - when Pip was given "the scaly tips of the drumsticks of the fowls, and ... those obscure corners of pork of which the pig, when living, had had the least reason to be vain."

"My sister having so much to do, was going to church vicariously; that is to say, Joe and I were going.

It's all just so funny! Pip's sister is like some demonic whirlwind, and the pompous visitors full of self-righteousness are a scream too :D

In chapters 5 and 6, we're never really told why Joe and Pip accompany the soldiers to look for the convicts. They have to run along at quite a pace to keep up. Is it just for the thrill, maybe? They certainly don't feel at all keen to catch them, and in fact feel quite sorry for the convicts when they are caught.

In chapters 5 and 6, we're never really told why Joe and Pip accompany the soldiers to look for the convicts. They have to run along at quite a pace to keep up. Is it just for the thrill, maybe? They certainly don't feel at all keen to catch them, and in fact feel quite sorry for the convicts when they are caught.I seem to remember reading that the general public were often on the side of the convict, as people could be transported - or even hanged - for very minor offences indeed, such as stealing fruit from a market stall. So more major crimes were unlikely, and that perhaps explains the sympathy we see for them here, rather than any vengeance often displayed by crowds, whipping themselves up at public hangings. We can also see, even at this early stage, that there is no love lost between these two convicts, and that "Pip's" convict is very keen to impress on the soldiers that he had captured the other one for them. It makes us wonder why.

Pip's sister is reminding me of Lady Dedlock's French lady's maid, Hortense )who was actually based on a real murderess) in Bleak House. A whirlwind of demonic energy! On the other hand we don't know what privations she had to endure. Women of that time and class frequently worked like domestic slaves. Perhaps she's more similar to Mrs. Snagsby (also in Bleak House), ie. a quarrelsome wife, who isn't really a bad person at all, but just very bitter and frustrated.

Some of this is in living memory ... For instance all my grandmother ever used was one sort of green soap for everything, including washing sheets etc. She had no hot water on tap - had to boil it all. No washing machine, no bathroom, no inside toilet. Tin bath in front of the coal fire. You had to go outside and up some steps to the toilet - through the snow sometimes. Everything was cooked on a range in very small living room. Yet she brought up a large family.

Its no surprise really that in photographs the women looked so grim and determined. They had to be! I remember all this very clearly, as I used to visit her twice a week as a child, and bring some buckets of coal up from the cellar.

On the other hand, she is a ripe target for one of Dickens's grotesque exaggerations, isn't she?

It's tempting to think that Joe is lazy in the house, assessing him by modern standards. BUT his life in the forge can't have been an easy one. When he told Pip his story, it was clear that he took both Pip's sister and Pip on for life - a ready-made family. He also defends Pips's sister's behaviour when Pip hints anything critical behind her back. No, Joe is indeed a good soul :)

Interestingly convicts in Britain were not actually send to America at the time of Great Expectations any more. That stopped in 1776, and after then they were sent to Australia. It's estimated that 140,000 criminals were transported to Australia between 1810 and 1852 (8 years before this was published - it was actually abolished in 1857). It was for life. If a convict ever returned to Britain, they were hanged (by law, until 1834), even though the original offences were sometimes quite minor by modern standards.

Interestingly convicts in Britain were not actually send to America at the time of Great Expectations any more. That stopped in 1776, and after then they were sent to Australia. It's estimated that 140,000 criminals were transported to Australia between 1810 and 1852 (8 years before this was published - it was actually abolished in 1857). It was for life. If a convict ever returned to Britain, they were hanged (by law, until 1834), even though the original offences were sometimes quite minor by modern standards.I'm trying to work out Dickens's attitude to emigration and am remembering an earlier novel, Bleak House. In that, he has the appallingly single-minded Mrs. Jellyby, whom he based on the missionary Caroline Chisholm, founder of the "Family Colonisation Loan Society" involved in the assisted emigation of young families to Australia for a better life. He does seem to be ambivalent about this - judgemental on the one hand (because of her neglect of what he saw as her family duties) and approving the concept on the other.

And only 5 years after Great Expectations began to be first serialised, 2 of Dickens' own sons were encouraged to do this, Alfred in 1865 and Edward ("Plorn") in 1868. Odd that this desirable state was so close in time to the novel he was writing, which is full of dread of an unknown land. He must have been casting his mind back quite a way!

Oh those five little lozenges" were based on actual graves apparently! According to Dickens's son, "St. James's Church" in the village of Cooling, was Dickens's favourite church:

Oh those five little lozenges" were based on actual graves apparently! According to Dickens's son, "St. James's Church" in the village of Cooling, was Dickens's favourite church:

I mentioned that the passage in the novel with the convicts, near the marshes were set around that area (comment 432). In the churchyard at Cooling, are some child memorials - not just five but thirteen child graves all together, from two families in the village who were related:

link here for the article.

I like this illustration by John McLenan in 1860, where "Mrs. Joe" is giving Pip a good scrub just before his first visit to Satis House. This is exactly how I imagine Pip's sister, though some illustrators made her far more of a caricatured harridan.

I like this illustration by John McLenan in 1860, where "Mrs. Joe" is giving Pip a good scrub just before his first visit to Satis House. This is exactly how I imagine Pip's sister, though some illustrators made her far more of a caricatured harridan.

But I think it's when we meet Estella - and Miss Havisham in particular - that the illustrators show their true talent. The best ones of Satis House have a real gothic feel. My favourite of all is by Charles Green, in 1877. He was a famous Victorian watercolourist who often worked in monochrome. He has illustrated several of the "Pears Centenary edition of Dickens's Christmas Stories" I have :)

But I think it's when we meet Estella - and Miss Havisham in particular - that the illustrators show their true talent. The best ones of Satis House have a real gothic feel. My favourite of all is by Charles Green, in 1877. He was a famous Victorian watercolourist who often worked in monochrome. He has illustrated several of the "Pears Centenary edition of Dickens's Christmas Stories" I have :)

"Whether I should have made out this object so soon if there had been no fine lady sitting at it, I cannot say. In an arm-chair, with an elbow resting on the table and her head leaning on that hand, sat the strangest lady I have ever seen, or shall ever see.

She was dressed in rich materials,—satins, and lace, and silks,—all of white. Her shoes were white. And she had a long white veil dependent from her hair, and she had bridal flowers in her hair, but her hair was white. Some bright jewels sparkled on her neck and on her hands, and some other jewels lay sparkling on the table. Dresses, less splendid than the dress she wore, and half-packed trunks, were scattered about. She had not quite finished dressing, for she had but one shoe on,—the other was on the table near her hand,—her veil was but half arranged, her watch and chain were not put on, and some lace for her bosom lay with those trinkets, and with her handkerchief, and gloves, and some flowers, and a Prayer-Book all confusedly heaped about the looking-glass..

It was not in the first few moments that I saw all these things, though I saw more of them in the first moments than might be supposed. But I saw that everything within my view which ought to be white, had been white long ago, and had lost its lustre and was faded and yellow. I saw that the bride within the bridal dress had withered like the dress, and like the flowers, and had no brightness left but the brightness of her sunken eyes. I saw that the dress had been put upon the rounded figure of a young woman, and that the figure upon which it now hung loose had shrunk to skin and bone. Once, I had been taken to see some ghastly waxwork at the Fair, representing I know not what impossible personage lying in state. Once, I had been taken to one of our old marsh churches to see a skeleton in the ashes of a rich dress that had been dug out of a vault under the church pavement. Now, waxwork and skeleton seemed to have dark eyes that moved and looked at me. I should have cried out, if I could. "

Oooooh! *shuddders* How can people say that Dickens's descriptions are too long?!

This one was by Harry Furniss, a bit later in 1910. It's quite dramatic, and the way it's executed makes me think of cobwebs! Miss Havisham is terrifyingly gaunt too:

This one was by Harry Furniss, a bit later in 1910. It's quite dramatic, and the way it's executed makes me think of cobwebs! Miss Havisham is terrifyingly gaunt too:

"Satis House", was based as I mentioned before on "Restoration House" in Rochester. Charles II stayed there on his return to England in 1660, restoring the English monarchy after Oliver Cromwell. But also the word "satis" has an interesting derivation, and several layers of meaning for those who know the entire story. It is is an Indian word which describes the act of a widow throwing herself on her husband's funeral pyre.

"Satis House", was based as I mentioned before on "Restoration House" in Rochester. Charles II stayed there on his return to England in 1660, restoring the English monarchy after Oliver Cromwell. But also the word "satis" has an interesting derivation, and several layers of meaning for those who know the entire story. It is is an Indian word which describes the act of a widow throwing herself on her husband's funeral pyre.

This is such a visual novel! The stuff of all horror films forever after! No wonder it's been filmed so many times. Yet reading the passages of description they are so much richer and denser than can ever be captured through pictures. Here's my favourite part, from Pip's second visit to Satis House:

This is such a visual novel! The stuff of all horror films forever after! No wonder it's been filmed so many times. Yet reading the passages of description they are so much richer and denser than can ever be captured through pictures. Here's my favourite part, from Pip's second visit to Satis House:"It was spacious, and I dare say had once been handsome, but every discernible thing in it was covered with dust and mould, and dropping to pieces. The most prominent object was a long table with a tablecloth spread on it, as if a feast had been in preparation when the house and the clocks all stopped together. An epergne or centrepiece of some kind was in the middle of this cloth; it was so heavily overhung with cobwebs that its form was quite undistinguishable; and, as I looked along the yellow expanse out of which I remember its seeming to grow, like a black fungus, I saw speckled-legged spiders with blotchy bodies running home to it, and running out from it, as if some circumstances of the greatest public importance had just transpired in the spider community.

I heard the mice too, rattling behind the panels, as if the same occurrence were important to their interests. But, the blackbeetles took no notice of the agitation, and groped about the hearth in a ponderous elderly way, as if they were short-sighted and hard of hearing, and not on terms with one another.

These crawling things had fascinated my attention and I was watching them from a distance, when Miss Havisham laid a hand upon my shoulder. In her other hand she had a crutch-headed stick on which she leaned, and she looked like the Witch of the place."

I had completely forgotten about all the creepy-crawlies and only remembered the dustiness and gothic elements.

I'd also forgotten the (presumbly older Pip) narrator's knowing attitude toward the relatives of Miss Havisham. This dual aspect is so clever - we have the young Pip's impressions and feeling and also the older Pip's insight. (If we trust the narrator, of course.)

It seems even more powerful being reported through young eyes, without much perspective, knowledge of the world or a wider context. We might speculate about how old Miss Havisham is, but it's as well to bear in mind how old you thought middle-aged people were when you were little.

There is a family story of how when I was taken to a museum as a small child, and shown an ancient tombstone, I said, "But that's even older than Grandma!"

It became a family motto for ever afterwards, but was actually very meaningful to me!

Sometimes Dickens's heroes start off with a very low self-image or lack of identity. He writes this idea time and time again. In David Copperfield the protagonist went through many name changes - more than any other I believe. There was "Davy", "Master Davy", "David" "Master Copperfield", "Daisy", "Dodie", "Mister Copperfield" ... and probably some I've forgotten. Each seemed to indicate both the way he was viewed by others, and also his own sense of self-worth. If we relate it to our own personal nicknames, pet names, our friends' names for us and our formal names, it can be very revealing.

Sometimes Dickens's heroes start off with a very low self-image or lack of identity. He writes this idea time and time again. In David Copperfield the protagonist went through many name changes - more than any other I believe. There was "Davy", "Master Davy", "David" "Master Copperfield", "Daisy", "Dodie", "Mister Copperfield" ... and probably some I've forgotten. Each seemed to indicate both the way he was viewed by others, and also his own sense of self-worth. If we relate it to our own personal nicknames, pet names, our friends' names for us and our formal names, it can be very revealing.Pip is an orphan, as many of the children in Dickens's works are, and he seems to be referred to as an object - less than human - quite often. The very first paragraph of the novel is about Pip's name, "Philip Pirrip" Early on the convict calls him a dog, and one "good enough to eat". In chapter 4 Mr Pumblechook (and Mrs. Joe) calls Pip a "squeaker" and imply that he might be served at the dinner table. Mr Pumblechook also calls Pip "sixpennorth of halfpence".

Food and money seem to be central to this novel.

Pip's lack of name and identity, and being classed as an edible animal or object are certainly good ways to quash a small boy's energetic nature - or any self-esteem. Children had to be "seen and not heard" as we all know. I'm put in mind of photographs of classrooms with all the children sitting at a desk with their hands folded behind their backs and the teacher with a wooden rule ready to strike. And these were the "privileged" ones who went to school!

As well as food, and aggression and violence, I'm also starting to notice another motif; that of time, specifically represented by clocks.

We saw how John McLenan depicted Pip's sister, (in 1860) and this is his illustration for the young Pip walking Miss Havisham round the table with the great bride-cake on:

We saw how John McLenan depicted Pip's sister, (in 1860) and this is his illustration for the young Pip walking Miss Havisham round the table with the great bride-cake on:

The best illustration for the haughty young Estella, in my opinion, is this one by Harry Furniss, in 1910:

The best illustration for the haughty young Estella, in my opinion, is this one by Harry Furniss, in 1910:

"Come here! You may kiss me, if you like."

This took place just after she had been peeping at Pip (view spoiler).

Oh, but look at Charles Green again! Look at the "lighting" effect. It glows, and seems almost photographic:

Oh, but look at Charles Green again! Look at the "lighting" effect. It glows, and seems almost photographic:

Up to chapters 12 and 13, and there are definitely recurring themes of incarceration, imprisonment and violence; the language itself is very violent.

Up to chapters 12 and 13, and there are definitely recurring themes of incarceration, imprisonment and violence; the language itself is very violent.The boy Pip seems to have a strong sense of guilt, which intrigues me. Where does it stem from? Is it something he is taught at church? (Does he go to church? He visits his parents' graves, so perhaps so). Is it beaten into him by his sister - and if so why does he give this credence - or has he been so downtrodden that he feels guilty for living at all? (This also seem to be a recurring theme in Dickens). Is it Joe's example he looks to? Or does he have a sense of "natural justice"?

I think these are all vague feelings we have about the "guilt" sensed by the young Pip, but I think overlaid with this is the older Pip's inaccurate memory perhaps - or unreliable telling - of what he actually experienced. It was probably more a fear of being found out than anything, I suspect. The older Pip perhaps thought it flattering to suggest that he was feeling guilty as a young boy.

The other thing I find difficult to square in Pip is his desire for self-improvement at such an early age. I think this is Charles Dickens writing himself into the part, much as he has done with several of his other heroes.

The other thing I find difficult to square in Pip is his desire for self-improvement at such an early age. I think this is Charles Dickens writing himself into the part, much as he has done with several of his other heroes.Estella represents another world, a world that seems unattainable and yet very tempting and superior to Pip, and his desire seems to date from this point. She makes him feel small, coarse and dirty, and he then begins to notice that in Joe too - and yet feel ashamed of himself for doing so.

It is just believable that this is the young Pip speaking, yet I still wonder. He could plainly see the ruin, filth and chaos around in Satis House. Estella is apparently a product of that. It's not much to admire, is it? OK he is smitten with Estella, despite her contempt for him, but his ideas of what is desirable are confused. He wants to learn to write - but we have not seen that she can do so. He wants to be a gentleman, but the person who invites him to confide in her (Miss Havisham) appears to be very odd, even to him. What is it about this household which makes him think it is better than the life he would have at the forge when he was older?

And why is he ashamed of Joe's embarrassing behaviour - but not equally of Miss Havisham's extremely odd appearance and lifestyle? He went there every other day, so he probably feels a sort of loyalty there too.

We get a sense of the older Pip when the narrator refers to Mr. Pumblechook as "that ass" and "a miserable man". I felt this was unlikely to be the young Pip. It must be the older narrator, with his experience, passing judgement.

We get a sense of the older Pip when the narrator refers to Mr. Pumblechook as "that ass" and "a miserable man". I felt this was unlikely to be the young Pip. It must be the older narrator, with his experience, passing judgement.I guess the folk at Satis House, none of whom had to work for their money, would seem to be deserving of more respect. At this time that was the "code" in British society. So if Pip thought something else, it would soon be drummed out of him. Gentlemen never worked for a living!

It puts me in mind of how scathing Steerforth was about that poor teacher in David Copperfield, and we have many examples of people in "business" or "trade" being thought beneath contempt by the gentry, never mind the aristocrats, throughout Victorian literature.

Books mentioned in this topic

Our Mutual Friend (other topics)Nicholas Nickleby (other topics)

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (other topics)

Bleak House (other topics)

The Pickwick Papers (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

Charles Dickens (other topics)Anne Brontë (other topics)

Henry Mayhew (other topics)

Harland S. Nelson (other topics)

John Forster (other topics)

More...

Yesterday I read this article link here about him signing on as a founding member of "The Ghost Club" at Trinity College. (Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was also to join).