Litwit Lounge discussion

The Classics

>

Jean's Charles Dickens Challenge

From chapter 55 - What an enthralling, powerful piece of writing - so symbolic - and just the perfect (view spoiler)

From chapter 55 - What an enthralling, powerful piece of writing - so symbolic - and just the perfect (view spoiler)Wow! It's so visual. I am posting it here so I don't lose it.

And the ending we all wanted :)

I do love how Dickens always makes the good guys win (whatever they might suffer through the story) - and always ties up the loose ends and tells us what happens to everybody we're wondering about :)

I do love how Dickens always makes the good guys win (whatever they might suffer through the story) - and always ties up the loose ends and tells us what happens to everybody we're wondering about :)And still more to come!

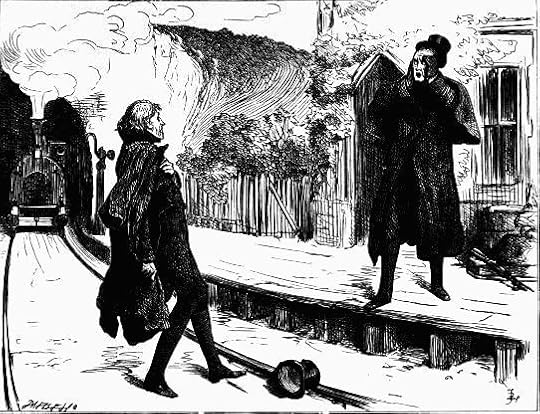

An image:

An image:(view spoiler)

"He saw the face change from its vindictive passion to a faint sickness and terror — "

Illustrator - Fred Barnard

On the whole I much prefer the illustrations by "Phiz". Amazing detail, character and atmosphere, such as in this one approaching the end of the book, showing Dombey musing,

On the whole I much prefer the illustrations by "Phiz". Amazing detail, character and atmosphere, such as in this one approaching the end of the book, showing Dombey musing,

"Let him remember it in that room, years to come."

Finished my review of Dombey and Son at last! Here it is

Finished my review of Dombey and Son at last! Here it isA GR friend (John F. ) said to me of this book:

"Great review, as usual, Jean. Definitely a five-star book. But I still think that Dickens' attempts to produce a planned novel do not come off fully. The discontinuity at the death of Paul junior, the disappearance of characters for overlong periods, and the number of superfluous characters mean that the book is still the usual Dickens mixture. Still not a true narrative, even if nearer to that, but still episodic, picaresque and melodramatic. But, a great book."

My response:

I quite like how the characters come and go John! It means I have time to recover from the drama of one episode by concentrating on another. And there is a definite difference I think in the way the themes all intertwine, whereas before he used quite a bit of deus ex machina when things didn't go quite as planned! I have to confess I didn't notice any discontinuity - perhaps I was so affected by the lead-up that any writing needed to be low-key at that point.

Superfluous characters? Well that's just Dickens's way, isn't it? There are never too many for my liking :)

I agree that there are more than in others' novels though. And it makes it hard to remember the intricacies of the plot in the same way. Perhaps this is what you personally require from a "true narrative"?

I vascillated between 4 and 5 stars. (I don't use halves.) I still think his best novels are to come, but this was significantly better as a piece of literature than the previous ones. The truth is, I think for me he is head and shoulders above the rest, but I'm aware that's probably a personal quirk. I do well not giving them all 5 stars really ... ;)

Oh and thanks!

Dickens matches Austen for humour (just different) and Hardy for social observation, but I feel he does both, not just either or, plus he has a broader remit than either.

That doesn't mean I don't admire and love them both too though! I'll happily pick up one for a reread. Who was it said that a book is not worth reading unless it can stand being reread? Was it C.S. Lewis perhaps?

DAVID COPPERFIELD

DAVID COPPERFIELD

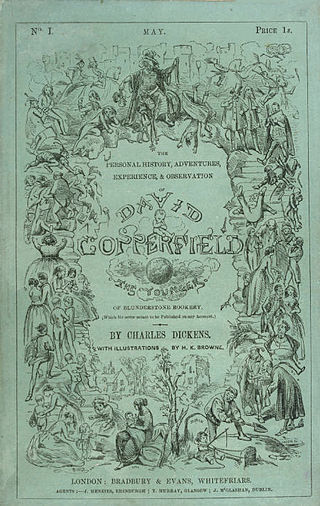

This is the cover from the first part of the serial in May 1849.

Before choosing the title below, he toyed with "Copperfield's Disclosures", "Mag's Diversions", "Copperfield Survey", "Copperfield's Confessions" and "Copperfield's Entire!"

"Copperfield's Disclosures" might just about have worked. Once you know though that so much of the content is lifted straight from autobiographical notes he'd already written but felt too ashamed to publish, the subtitle "(Which He Never Meant to Publish on Any Account)" is just perfect - and quite poignant really.

David Copperfield

David CopperfieldThe full title is "The Personal History, Adventures, Experience and Observation of David Copperfield the Younger of Blunderstone Rookery (Which He Never Meant to Publish on Any Account)"

We now know it as Charles Dickens's 8th novel, but like all the others, it was published in monthly installments. Here's the original schedule:

I – May 1849 (chapters 1–3)

II – June 1849 (chapters 4–6)

III – July 1849 (chapters 7–9)

IV – August 1849 (chapters 10–12)

V – September 1849 (chapters 13–15)

VI – October 1849 (chapters 16–18)

VII – November 1849 (chapters 19–21)

VIII – December 1849 (chapters 22–24)

IX – January 1850 (chapters 25–27)

X – February 1850 (chapters 28–31)

XI – March 1850 (chapters 32–34)

XII – April 1850 (chapters 35–37)

XIII – May 1850 (chapters 38–40)

XIV – June 1850 (chapters 41–43)

XV – July 1850 (chapters 44–46)

XVI – August 1850 (chapters 47–50)

XVII – September 1850 (chapters 51–53)

XVIII – October 1850 (chapters 54–57)

XIX-XX – November 1850 (chapters 58–64)

It was Dickens's own favourite, perhaps because it is semi-autobiographical . So how much, and why did he write it?

Well around the end of 1847, Charles Dickens had started to write a cathartic autobiography, to try to rid himself of some of his unhappy childhood memories - those he was too ashamed to mention in public. But when he reached the point of his unhappy love affair with the banker's daughter Maria Beadnell (immortalised later in Little Dorrit as Flora Finching), he didn't feel able to continue them. His wife also pointed out that publishing it would be very unkind to Charles Dickens's mother, but also here in David Copperfield as Mrs Micawber - and several other characters! He put it on the back burner.

The previous novel, Dombey and Son, had incorporated some of his early memoirs. The possibilities stirred his imagination. When he was staying in Brighton in February 1849, and started to write David Copperfield, the idea took hold of him again. He wrote to his friend and mentor John Forster,

"I really think I have done it ingeniously and with a very complicated interweaving of truth and fiction."

For many years, David Copperfield was the one book by Charles Dickens which the critics all agreed was a great novel. During the early part of the 20th century Angus Wilson reports that it was considered a "classical" novel, enjoying the same sort of status as War and Peace. Told in the first person, it is an internal or psychological novel. Nowadays though, others of Dickens's novels are sometimes awarded greater literary status.

It is a fantastic story! But in addition to this ... well reading the novel itself will reveal that :)

This one is so much more lighthearted than many. I very much like the fact that he is narrating it. And the titles of the chapter are so very simple "I am born", "I observe", "I have a change" are the first 3 (in the first installment). Now all the earlier books had a couple of sentences for the chapter headings, and sometimes they acted as spoilers as they told what would happen in the following chapter. I think perhaps many Victorian novels did that. But this is so very streamlined - and I'm noticing that in the dialogue too.

This one is so much more lighthearted than many. I very much like the fact that he is narrating it. And the titles of the chapter are so very simple "I am born", "I observe", "I have a change" are the first 3 (in the first installment). Now all the earlier books had a couple of sentences for the chapter headings, and sometimes they acted as spoilers as they told what would happen in the following chapter. I think perhaps many Victorian novels did that. But this is so very streamlined - and I'm noticing that in the dialogue too.And what a "tell" ... D.C. (David Copperfield) being C. D. (Charles Dickens) reversed.

The name of his home as well, "Blunderstone Rookery" is taken from a village Dickens had seen only a month previously, on a visit to Yarmouth and Lowestoft. And does the word "blunder" also perhaps indicate the way these two "babies" (as Betsey Trotwood termed them) approached the practicalities of life?

So far this novel has a sort of gleeful exuberance. Almost as if he knew it was going to be a personal favourite. Later he said to someone,

So far this novel has a sort of gleeful exuberance. Almost as if he knew it was going to be a personal favourite. Later he said to someone,"I don't mind confiding to you, that I can never approach the book with perfect composure, it had such perfect possession of me when I wrote it."

I think you can sense a sort of excitement bubbling up in him - a lighter touch altogether - and more readability. There is a definite difference from his earlier ones. Yet we're very conscious of David's inner thoughts - and already he's impressed on us how powerful and sharp his memory is. I guess that's why Angus Wilson calls it,

"a Proustian novel of the shaping of life through the echoes and prophecies of memory".

I was startled to read today that David Copperfield was the first book which Fyodor Dostoevsky asked for, in hospital after his long imprisonment in Siberia - without books. And that it had a great influence on his work! I haven't read any but it seems ... unexpected somehow.

How is this novel different from

Nicholas Nickleby

?

How is this novel different from

Nicholas Nickleby

? They both seem to be coming-of-age stories, with a young man at their centre. But Nicholas Nickleby is quite deliberately theatrical, (in every sense, not just the sections about the travelling acting troupe) because of who he dedicated it to. As you read it you can just imagine Charles Dickens strutting around the stage, declaiming and pronouncing judgement - some parts are very much not to our current taste! It's melodramatic, over-sentimental - all that, yes - but it also has some fantastic characters, observations of social conscience and a marvellous storyline.

In 1980 there was an epic phenomenon, and one for the history books. A performance of Nicholas Nickleby, 8 and a half hours long, performed by the RSC (Royal Shakespeare Company) over 2 evenings at the Aldwych Theatre. An amazing cast - Nicholas himself was played by Roger Rees.

It was the first thing ever broadcast - as a live transmission - by Channel 4, which in those days was hailed as a brand-new TV Channel dedicated to the Arts. (No longer, sadly!) A real labour of love.

It was revived a couple of times later - once on Broadway I believe. Alun Armstrong played the main role for a while; around 1982. He was with the RSC for 8 or 9 years - he's an incredibly versatile actor. I think he must love Charles Dickens too, as he's been in virtually every good dramatisation of the novels that I've seen!

The original mammoth production was incredibly hard to obtain tickets for, and there is a DVD but it's quite rare. There are plenty of DVDs of ordinary TV dramatisations of course - one of which was very good - and a film or two.

One of my little fantasies :)

I particularly liked the descriptions of Peggotty's buttons flying off every time she became emotional! Perhaps it wasn't so unusual ... I remember my mother saying that when she was a child they had to cut off their buttons every time a garment was washed, and sew them back on again! Otherwise they'd get broken when they were put through the mangle (rollers to squeeze out the surplus water). Life certainly was hard work in those days. And what a great image :)

I particularly liked the descriptions of Peggotty's buttons flying off every time she became emotional! Perhaps it wasn't so unusual ... I remember my mother saying that when she was a child they had to cut off their buttons every time a garment was washed, and sew them back on again! Otherwise they'd get broken when they were put through the mangle (rollers to squeeze out the surplus water). Life certainly was hard work in those days. And what a great image :)I liked this bit too, just a little cameo of a character who is destined never to appear again,

"it was, to the last, her proudest boast, that she never had been on the water in her life, except upon a bridge; and that over her tea (to which she was extremely partial) she, to the last, expressed her indignation at the impiety of mariners and others, who had the presumption to go 'meandering' about the world. It was in vain to represent to her that some conveniences, tea perhaps included, resulted from this objectionable practice. She always returned, with greater emphasis and with an instinctive knowledge of the strength of her objection, 'Let us have no meandering.'"

It was John Forster who suggested that Charles Dickens should write it in the first person. I think he was right - it's making an enormous difference! And I think that even with the latter part of the title "(Which He Never Meant to Publish on Any Account)" he's confusing or maybe subsuming himself with David.

The best TV dramatisation I know of David Copperfield (did you get my not-so-subtle segue there?) is a mini-series from 1999.

The best TV dramatisation I know of David Copperfield (did you get my not-so-subtle segue there?) is a mini-series from 1999. Here are the other main characters:

Clara Copperfield (David's mother) - Emilia Fox

Peggotty - Pauline Quirke

Dan Peggotty - Alun Armstrong|4570951]

Betsey Trotwood - Maggie Smith

Murdstone - Trevor Eve

Barkis - Michael Elphick

Mrs. Gummidge - Patsy Byrne

Miss Murdstone - Zoë Wanamaker

Creakle - Ian McKellen

Micawber - Bob Hoskins

Mrs. Micawber - Imelda Staunton

Uriah Heep - Nicholas Lyndhurst

Mr. Spenlow - James Grout

Mrs. Crupp - Dawn French

Narrator - Tom Wilkinson

Milkman - Colin Farrell

Mrs. Steerforth - Cherie Lunghi

Rosa Dartle - Clare Holman

and the young David was played by a virtually unknown child actor called ... Daniel Radcliffe ;)

I've just put the actors I think are famous world-wide in the list. Quite a few of these also played very memorable roles in other dramatisations of Dickens's novels.

Oh this is priceless logic from a child's point of view,

Oh this is priceless logic from a child's point of view,"and I could not help wondering, if the world were really as round as my geography book said, how any part of it came to be so flat. But I reflected that Yarmouth might be situated at one of the poles; which would account for it"

In earlier notes, Dr. Chillip was called "Dr. Morgan", and was based on the Dickens' family doctor - Dr. Charles Morgan - when they lived at Devonshire Terrace. His readers always thought they recognised him from some-one-or-other they knew in Suffolk, but they hadn't! The public must by now have been getting wise to the idea of Charles Dickens basing his characters on real people though :D

I'm up to the end of chapter 6 now, and love some of the characters' names - they're so appropriate!

I'm up to the end of chapter 6 now, and love some of the characters' names - they're so appropriate! Murdstone for instance, with his insistence that what everyone needs is "firmness". What does his name imply? Something dark - Murk? Murder? "Merde"? (French for excrement) followed by the hardness of "stone".

And the hard "metallic lady", his sister Jane, with her jewellery of "little steel fetters and rivets"; her bag with its heavy chain, snapping shut; the keys under her pillow. What a great description of her,

"a gloomy-looking lady she was; dark, like her brother, whom she greatly resembled in face and voice; and with very heavy eyebrows, nearly meeting over her large nose, as if, being disabled by the wrongs of her sex from wearing whiskers, she had carried them to that account."

Then there's Creakle with his whispery threatening non-voice - how does he "creak"? Is it in his bones? Does he creep about and make everyone feel his painful "creaking" joints? Apparently he was originally called "Crinkle" in an early draft, but "Creakle" is so much better! It also sounds a bit like "treacle" as if with his soft voice he's pretending to be all sweet, but is actually very menacing.

I have been finding out about some more of the characters' origins too.

I have been finding out about some more of the characters' origins too.Mr Creakle :

Just as in Nicholas Nickleby, "Dotheboys Hall" was based on an actual school, in this novel Charles Dickens bases "Salem House" on an appalling school he attended as a child, "Wellington House Classical and Commercial Academy", which was run by a sadistic man called William Jones.

William Jones was the original for ... "Mr Creakle" of course! Charles Dickens once said that Jones was,

"by far the most ignorant man I have ever had the pleasure to know, who was one of the worst tempered men perhaps that ever lived, whose business it was to make as much out of us and put as little into us as possible".

Tommy Traddles :

Tommy Traddles has just come into the story, and will prove to be very important. He was also based on a real person, Sir Thomas Noon Talfourd a barrister, judge, M.P. and playwright, who became a close friend of Charles Dickens when side by side they fought against all the plagiarism of their works. Copyright was in its very early stages then, and the issue of pirate copies of his works was one of Dickens's bugbears. "Tommy Traddles" and the judge had a lot in common with their "personal diligence, gentle disposition, and journalistic output".

Charles Dickens described his "fervent admiration" of Talfourd, and dedicated the first book edition of The Pickwick Papers to him, telling his friend and mentor John Forster that it was,

"a memorial of the most gratifying friendship I have ever contracted."

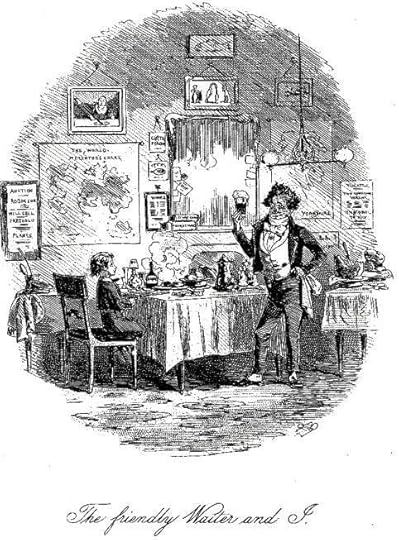

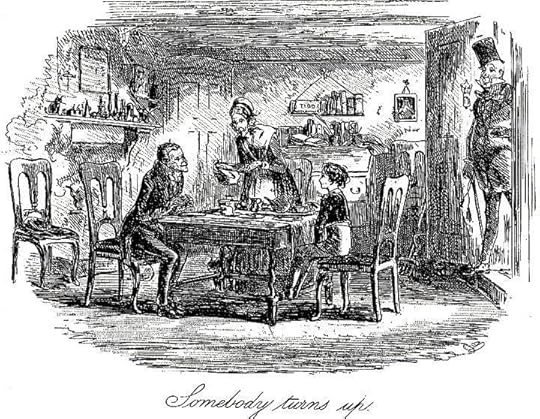

There are so many great episodes in these first few chapters - they're really crammed with them! I love the episode of the waiter, (view spoiler) - and the accompanying illustration by "Phiz":

There are so many great episodes in these first few chapters - they're really crammed with them! I love the episode of the waiter, (view spoiler) - and the accompanying illustration by "Phiz":

which makes David look such a tiny little tot :) Apparently the artist Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz") included the map of the world to imply how much David had to learn and a faint image of the fox and stork from Aesop's Fables to put the idea of (view spoiler) in our minds.

Then wouldn't you know it, Steerforth, David's (view spoiler)

All this shows me how well Charles Dickens is getting into the mind of a child. This is the first novel he wrote from the first hand point of view. What I'm not sure of yet is whether the author's voice is also that of the narrator. How old is the older David meant to be? And is he he remembering truthfully, or are his views coloured by subsequent experience? How well do any of us remember our childhoods objectively?

I'm assuming we have a reliable narrator here, (not an unreliable one!) since Charles Dickens says there is a lot of him in it. In the preface to the Charles Dickens Edition of 1867 he wrote,

"Of all my books, I like this the best. It will be easily believed that I am a fond parent to every child of my fancy, and that no one can ever love that family as dearly as I love them. But, like many fond parents, I have in my heart of hearts a favourite child. And his name is

DAVID COPPERFIELD"

Mr. Creakle seems to be a direct parallel to the sadistic master William Jones, whom Dickens had as a child. I've just read this bit about Mr. Creakle,

Mr. Creakle seems to be a direct parallel to the sadistic master William Jones, whom Dickens had as a child. I've just read this bit about Mr. Creakle,"Here I sit at the desk again, watching his eye — humbly watching his eye, as he rules a ciphering-book for another victim whose hands have just been flattened by that identical ruler, and who is trying to wipe the sting out with a pocket-handkerchief. I have plenty to do. I don't watch his eye in idleness, but because I am morbidly attracted to it, in a dread desire to know what he will do next, and whether it will be my turn to suffer, or somebody else's. A lane of small boys beyond me, with the same interest in his eye, watch it too. I think he knows it, though he pretends he don't. He makes dreadful mouths as he rules the ciphering-book; and now he throws his eye sideways down our lane, and we all droop over our books and tremble. A moment afterwards we are again eyeing him. An unhappy culprit, found guilty of imperfect exercise, approaches at his command. The culprit falters excuses, and professes a determination to do better tomorrow. Mr. Creakle cuts a joke before he beats him, and we laugh at it, — miserable little dogs, we laugh, with our visages as white as ashes, and our hearts sinking into our boots."

How like children. So scared by the brutish bully Creakle, that not only are they cowed by him but join in the "joke", whilst knowing full well it is wrong. He instills both fear and cowardice in one fell swoop.

This reminded me of a bit in one of his essays in "Household Words", ("Our School", October 1851) where he noted that "the Chief" (William Jones) had a penchant for ruling ciphering-books, and then,

"smiting the palms of offenders with the same diabolical instrument".

Obviously this was an image which stuck. The description of Creakle beating the boys is indeed diabolical :(

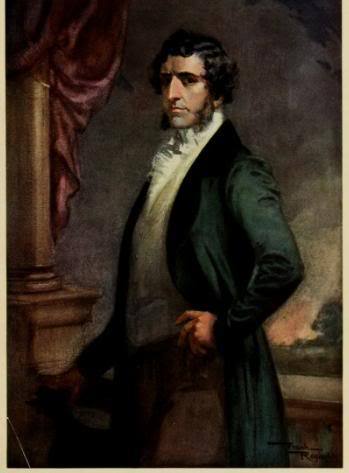

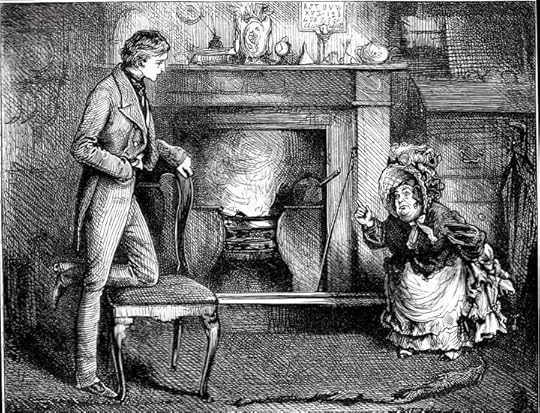

Of all the illustrations I've seen so far, I still prefer the originals by "Phiz" the best :) But here's quite a creditable one of Mr. Murdstone, from the 1920's, by Frank Reynolds:

Of all the illustrations I've seen so far, I still prefer the originals by "Phiz" the best :) But here's quite a creditable one of Mr. Murdstone, from the 1920's, by Frank Reynolds:

There are a lot of extremely sentimental and "cute moppet" type Dickens illustrations from the late Victorian period :( I do quite like this later portrait of Mr. Murdstone, but still prefer the original Phiz caricatures :) I think that this portrait conveys his "firm" disposition very well, and also you can see how a vain silly little flibbertigibbet like Clara would have fallen in love with his noble looks and bearing.

Chapter 11 is the most autobiographical so far. It's so obvious that David's (view spoiler) is a direct parallel to Charles Dickens's own experience in Warren's Blacking Factory. There are many passages very similar to his own account of that time. Here's an extract from John Forster's biography of Charles Dickens's early years from 1812 to 1842,

Chapter 11 is the most autobiographical so far. It's so obvious that David's (view spoiler) is a direct parallel to Charles Dickens's own experience in Warren's Blacking Factory. There are many passages very similar to his own account of that time. Here's an extract from John Forster's biography of Charles Dickens's early years from 1812 to 1842,"It is wonderful to me how I could have been so easily cast away at such an age. It is wonderful to me that, even after my descent into the poor little drudge I had been since we came to London, no one had compassion enough on me — a child of singular abilities, quick, eager, delicate, and soon hurt, bodily or mentally — to suggest that something might have been spared, as certainly it might have been, to place me at any common school. Our friends, I take it, were tired out. No one made any sign. My father and mother were quite satisfied. They could hardly have been more so if I had been twenty years of age, distinguished at a grammar-school, and going to Cambridge."

Bitter and heartfelt. Now compare a section at the beginning of chapter 11 in David Copperfield,

it is matter of some surprise to me, even now, that I can have been so easily thrown away at such an age. A child of excellent abilities, and with strong powers of observation, quick, eager, delicate, and soon hurt bodily or mentally, it seems wonderful to me that nobody should have made any sign in my behalf. But none was made; and I became, at ten years old, a little labouring hind in the service of Murdstone and Grinby."

It's almost a vicarious confession - or admission - of how he could not understand his own parents' reasoning here. Some parts are duplicated word for word! The descriptions of the two warehouses are similarly described, with some parts also being identical.

Does this sound at all familiar?

Does this sound at all familiar?(view spoiler)

No, not from chapter 11 of David Copperfield - though it might as well be! It's actually from John Forster's account of his life, from Charles Dickens's own experience again!

Little wonder then, that Dickens called this book his "favourite child"!

Murdstone and Grinby is another example of the clever puns or tricky word associations Dickens loves to include. "Grinby" makes us think of a "grindstone", with the stone part from "Murdstone". Here we are being told that David is "having his nose put to the grindstone".

Wilkins Micawber is perhaps the most well-known parallel to a real person in Dickens's life. He's a direct portrait of Dickens's own father - an improvident gentleman - and his history in David Copperfield also mimics real life. What isn't mentioned quite so often is that his wife is also heavily based on his real-life mother. In fact we first saw a representation of Dickens's mother in Nicholas Nickleby, where again she was caricatured as the protagonist's mother. She comes up in later novels too. Dickens clearly feels he has to exorcise these memories somehow, without betraying his family - they come up so often!

Wilkins Micawber is perhaps the most well-known parallel to a real person in Dickens's life. He's a direct portrait of Dickens's own father - an improvident gentleman - and his history in David Copperfield also mimics real life. What isn't mentioned quite so often is that his wife is also heavily based on his real-life mother. In fact we first saw a representation of Dickens's mother in Nicholas Nickleby, where again she was caricatured as the protagonist's mother. She comes up in later novels too. Dickens clearly feels he has to exorcise these memories somehow, without betraying his family - they come up so often! And then there's his own consciousness of being socially superior to his working class fellows and also more intelligent. He feels humiliated by being with them. We got that before with little Oliver Twist, never picking up the way of the Artful Dodger and his gang. Now we have a rerun, as David will not fraternise with Walker and Mealy Potatoes and is referred to as "the little gent" by some of the workers at the warehouse.

Mr. Dick:

Mr. Dick:

I'm now up to ch 16, and we've met some more of my favourite characters. I had been looking forward to meeting Mr. Dick again, as the last time I read this book I hadn't realised he was based on a real person. Aunt Betsey Trotwood says,

"'I suppose ... you think Mr. Dick a short name, eh? ...

You are not to suppose that he hasn't got a longer name, if he chose to use it ... Babley — Mr. Richard Babley — that's the gentleman's true name ... But don't you call him by it, whatever you do. He can't bear his name. That's a peculiarity of his. Though I don't know that it's much of a peculiarity, either; for he has been ill-used enough, by some that bear it, to have a mortal antipathy for it, Heaven knows.'"

'He has been CALLED mad ... I have a selfish pleasure in saying he has been called mad, or I should not have had the benefit of his society and advice for these last ten years and upwards'"

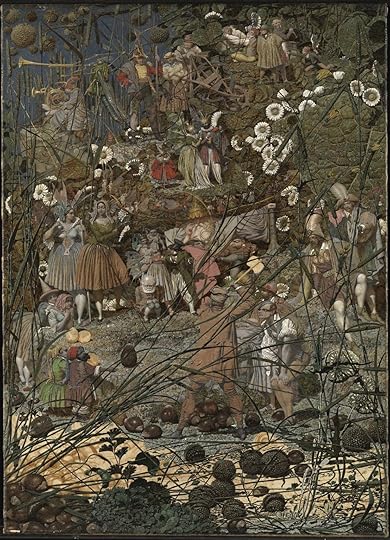

"Richard Babley" is based on the Victorian artist Richard Dadd, most famous for his incredibly detailed painting "The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke", which he painted in Bethlem Hospital (the original for the word "bedlam"). He had had what appears to be a psychotic illness, had murdered his father and was attempting to kill another man on a train, when he was apprehended and taken to the insane asylum.

The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke

It's in the Tate Gallery, in London. It is quite small, approx. 54 x 40cm, but incredibly precise and detailed. Surprisingly often, you find that reproductions of Richard Dadd's paintings are in fact details from this one.

I recently read an interesting bio of Richard Dadd Richard Dadd: The Artist and the Asylum by Nicholas Tromans, and that's where I discovered he was the original for "Mr. Dick". He was a very fashionable artist during Dickens's lifetime. Another interesting fact is that Richard Dadd was born in Chatham, Kent in 1817, the year before the Dickens family arrived there.

Here's my review of Richard Dadd's biography.

Charles I

Charles IAnother fact to bear in mind, when thinking of Mr. Dick's obsession with the idea that the facts in Charles the First's head had somehow got into his own, is the timing of the original serialisation of David Copperfield. It had started in May 1849, and by the time of the 4th issue - exactly when we meet Mr. Dick - it was August 1849.

This was the Bicentenary of the execution of Charles I. No doubt most people reading the story would be aware of the importance to history of this beheaded monarch.

Uriah Heep:

Uriah Heep:

He of the clammy hands - one of Dickens's most deliciously awful grotesques :) Here is our first encounter with him,

"The low arched door then opened, and the face came out. It was quite as cadaverous as it had looked in the window, though in the grain of it there was that tinge of red which is sometimes to be observed in the skins of red-haired people. It belonged to a red-haired person — a youth of fifteen, as I take it now, but looking much older — whose hair was cropped as close as the closest stubble; who had hardly any eyebrows, and no eyelashes, and eyes of a red-brown, so unsheltered and unshaded, that I remember wondering how he went to sleep. He was high-shouldered and bony; dressed in decent black, with a white wisp of a neckcloth; buttoned up to the throat; and had a long, lank, skeleton hand, which particularly attracted my attention, as he stood at the pony's head, rubbing his chin with it, and looking up at us in the chaise."

Here's an illustration by Fred Barnard of Uriah Heep,

Now what's surprising is not so much that he's based on a real person - we're used to that with Dickens by now - but just exactly who it is. His physical appearance and mannerisms are based on ... Hans Christian Andersen!

I think I may have mentioned before that there was no love lost between these two. Originally they were the best of friends, but Hans Christian Andersen did not have a proper home of his own, and scrounged visits to his friends, always overstaying his welcome. When he finally left, Dickens scrawled on the mirror that he had stayed for 5 long weeks,

"which seemed to the family simply ages!"

and one of Dickens's daughters, who had originally thoroughly enjoyed Hans Christian Andersen's storytelling sessions agreed, eventually referring to him as, "the bony bore". Here he is,

and there's another great photo of the eccentric author on his Goodreads author page.

It does seem a little unkind of Charles Dickens, this particular portrayal, however mingy his erstwhile friend had been!

This illustration by Phiz shows when (extremely coincidentally and fortuitously to the plot), in chapter 17 (view spoiler)

This illustration by Phiz shows when (extremely coincidentally and fortuitously to the plot), in chapter 17 (view spoiler)

It's really packed with detail! We've learnt about the Heeps' "corkscrewing" out of facts about David, and there is a corkscrew hanging on the wall.

There are other metaphors too, such as a stuffed owl (representing the predatory watchfulness of the Heeps) the mousetrap and cats. There are both ceramic cats, and a real cat next to Mrs. Heep.

And why is the doorknocker pulling such a face? Who is actually annoyed? Or is it because David is annoyed at these characters meeting up?

I usually really dislike the illustrations by Kyd, which don't seem to bear any relation to the ext! But for once, I actually like this illustration by Kyd, (J. Clayton Clarke)

I usually really dislike the illustrations by Kyd, which don't seem to bear any relation to the ext! But for once, I actually like this illustration by Kyd, (J. Clayton Clarke)

"I am well aware that I am the 'umblest person going, let the other be where he may. My mother is likewise a very 'umble person. We live in a numble abode, Master Copperfield, but have much to be thankful for."

OK so we know that Uriah Heep's physical appearance body language:

OK so we know that Uriah Heep's physical appearance body language:"He had a way of writhing when he wanted to express enthusiasm, which was very ugly; and which diverted my attention ... to the snaky twistings of his throat and body"

and general parsimony and meanness was based on Charles Dickens's rather jaded view of Hans Christian Andersen.

But other critics have commented that Uriah Heep's character is based on Blifil from The Adventures of Tom Jones. Apparently he was the antagonist of the story, whose vile nature was camouflaged by "sugary hypocrisy"

Also, there might be a biblical connection to Uriah. In the Bible, Uriah the Hittite was the husband of Bathsheba. The Biblical David was enamoured of Bathsheba, and in David Copperfield we have two male characters, both of whom admire Agnes Wickfield.

I do like the way Charles Dickens selects his names according to whether the characters are to be admired or despised! So we had the odious headmaster Mr Creakle and now we have an admirable teacher Dr. Strong. You couldn't get a more positive name! He apparently is based on a teacher whom Charles Dickens had when he was very young. But, interestingly, the name "Strong" is actually taken from his own experience too ...

I do like the way Charles Dickens selects his names according to whether the characters are to be admired or despised! So we had the odious headmaster Mr Creakle and now we have an admirable teacher Dr. Strong. You couldn't get a more positive name! He apparently is based on a teacher whom Charles Dickens had when he was very young. But, interestingly, the name "Strong" is actually taken from his own experience too ...

Aunt Betsey Trotwood:

Aunt Betsey Trotwood:

Miss Betsey Trotwood is based on a Miss Mary Pearson Strong, who used to reside at 12, High Street, Broadstairs, Kent. This is now the location of The Dickens House Museum.

When Charles Dickens went to stay in Broadstairs for the first time in 1837 he was twenty-five years old and already famous (as the author of The Pickwick Papers). Taking lodgings with Miss Pearson Strong he carried on working on the book, and was to return to the town often. It was in Broadstairs where he found much of the inspiration for Aunt Betsey Trotwood.

Dickens's own son, Charles, wrote that Miss Strong was a kindly and charming old lady who used to feed him tea and cakes! It was Miss Pearson Strong who was,

"firmly convinced of her right to stop the passage of donkeys in the front of her cottage. Miss Strong would chase the seaside donkey-boys from the piece of garden in front of her cottage".

Although Charles Dickens was to faithfully recall the donkey incident in his character of Betsey Trotwood, Dickens moved the location to Dover. Charles Dickens's son surmised that this was done to avoid any embarrassment to Miss Strong.

Charles Dickens's description of Aunt Betsey's cottage is through the eyes of the young David Copperfield. There is a square gravelled garden full of flowers, and a parlour with old-fashioned furniture. The garden is still there, and still belongs to the house, although now it is across a busy road from "The Dickens House Museum" in Broadstairs.

It's somewhere I would very much like to visit some day!

Nope. I do not like Mrs Markleham (Annie Strong's mother, and consequently mother-in-law to Dr. Strong) and her silly hat,

Nope. I do not like Mrs Markleham (Annie Strong's mother, and consequently mother-in-law to Dr. Strong) and her silly hat, "Her name was Mrs. Markleham; but our boys used to call her the Old Soldier, on account of her generalship, and the skill with which she marshalled great forces of relations against the Doctor. She was a little, sharp-eyed woman, who used to wear, when she was dressed, one unchangeable cap, ornamented with some artificial flowers, and two artificial butterflies supposed to be hovering above the flowers ... it always made its appearance of an evening ... the butterflies had the gift of trembling constantly; and ... improved the shining hours at Doctor Strong’s expense, like busy bees."

Apart from all the suspicions we are being encouraged to harbour about her motives, she's such an opinionated old biddy, of the type Dickens writes so well.

How many objectionable people have you known to whom this could be attributed, whether overtly or merely indicated by their behaviour?

“I must really beg that you will not interfere with me, unless it is to confirm what I say.”

LOL! What a gem! :D

I'm also loving to hate - but slightly admire - Rosa Dartle

I'm also loving to hate - but slightly admire - Rosa Dartle (brackets here for an indignant expostulation - how can people say that Dickens's female characters are insipid? Look at this one - or the embittered and disenchanted Alice Marwood in Dombey and Son - and a very similarly motivated resentful one to come, (view spoiler) in Little Dorrit. End of ranty brackets ...)

She is described - very powerfully - mostly from young David's point of view I think, as it has a very negative slant, as if her outward appearance was necessarily an indication of her character, which hopefully an older wiser David (the narrator) would not still feel.

But look at the sarcasm in her mean malicious "darts" (another wonderful punning name from Dickens!)

"'Really!' said Miss Dartle. 'Well, I don't know, now, when I have been better pleased than to hear that. It's so consoling! It's such a delight to know that, when they suffer, they don't feel! Sometimes I have been quite uneasy for that sort of people; but now I shall just dismiss the idea of them, altogether"

This serves the purpose of highlighting Steerforth's (view spoiler)

And what a fantastic cliffhanger of forboding at the end of chapter 21 with,

(view spoiler)

Miss Mowcher:

Miss Mowcher:

as depicted by Sol Eytinge - Boston 1867.

What a weird oddball character! She's often missed out of dramatisations, for reasons of space, but perhaps also because casting might present some problems given her appearance!

You know what I'm going to say, don't you? Yes, she was based on a real person - his wife Catherine's chiropodist Mrs. Jane Seymour Hill.

Here's what Charles Dickens's biographer John Forster wrote,

"Thinking a grotesque little oddity among his acquaintance to be safe from recognition, he had done what Smollett did sometimes, but never Fielding, and given way, in the first outburst of fun that had broken out around the fancy, to the temptation of copying too closely peculiarities of figure and face amounting in effect to deformity ..."

It's surprising that he didn't realise he would give offence in this, since recently a newspaper had published a scathing description of the profession as,

"the very lowest description of charlatanism." The article even went so far as to name and describe Mrs. Jane Seymour Hill as,

"the most eminent amongst female operators is a dwarf, who, on a very genteel-looking card, thus describes herself - corn-operator. This interesting little lady is one of the greatest London characters; she may be seen in all parts of the town, riding in a chaise in company with her brother, who is also a dwarf."

Still smarting from such publicity, it was presumably the last straw for Mrs. Hill to find another description - complete this time with her "catch-phrase" "Ain't I volatile" in the pages of David Copperfield. She threatened a lawsuit, writing,

"I have suffered long and much from my personal deformities, but never before at the hands of a man so highly gifted as Charles Dickens."

Dickens was appalled at this and hurriedly backed off, apologising and saying he was "grieved and surprised beyond measure. That he had not intended her altogether."

He even offered to change what he had written, but presumably did not do so, or we would no longer be able to read about his quirky grotesque character Miss Mowcher:

Miss Mowcher, Steerforth and David by Phiz.

Apparently Charles Dickens did change the character of Miss Mowcher a little in future episodes. His original intention had been for her to help in (view spoiler)

Apparently Charles Dickens did change the character of Miss Mowcher a little in future episodes. His original intention had been for her to help in (view spoiler)Then towards the end of the novel she (view spoiler). At around the same time three quarters through the novel Charles Dickens's daughter Dora Annie was born, and called after the character in David Copperfield. The real-life Dora died after just a few months.

It's quite clever I think how Dickens managed to completely rewrite and switch about the character of Miss Mowcher. After her remonstrances of David, about not taking her at face value, with all the repetitions of "Ain't I volatile!" and eccentric behaviour, and to consider what fate she and other members of her family also affected by dwarfism might otherwise suffer, he (and we) are now left with a completely different impression of her:

"Take a word of advice, even from three foot nothing. Try not to associate bodily defects with mental, my good friend, except for a solid reason."

His mentor and biographer John Forster notes:

"That he felt nevertheless he had done wrong, and would now do anything to repair it. That he had intended to employ the character in an unpleasant way, but he would, whatever the risk or inconvenience, change it all, so that nothing but an agreeable impression should be left. The reader will remember how this was managed, and that the thirty-second chapter went far to undo what the twenty-second had done."

Steerforth:

Steerforth:

I've never been able to discover whether he was based on a real person. I don't think he was - he's more of an experiment in charm, I think, and the influence a charismatic person of this type has over everyone he meets.

There are definitely echoes of other "heroic" and unheroic characters, but no actual person as far as I can tell - unlike many of his other characters major and minor!

But this time through I noticed his name - "steer forth", and when he is with the Peggottys we learn that he is quite an expert sailor. When in chapter 22 (view spoiler) What's the significance here? Meaning and double meanings. Steerforth talked about David as his "property" before. Is it just the boat which is his property? Stormy weather to come perhaps.

Dickens had a bit of a rant about the "Prerogative Office" in the next chapter. It started off as quite funny,

Dickens had a bit of a rant about the "Prerogative Office" in the next chapter. It started off as quite funny,"this Prerogative office of the diocese of Canterbury was altogether such a pestilent job, and such a pernicious absurdity, that but for it being squeezed away in a corner of St. Pauls Churchyard, which few people knew, it must have been turned completely inside out, and upside down, long ago"

but Dickens continued his complaints ad nauseum for about three pages - and then seemed to feel a bit embarrassed about it, and felt the need to justify it by saying it was "in its natural place" in the novel because its what "I" (David) was talking to Mr Spenlow about when they were walking along.

Come come Mr Dickens - who are you kidding?! Not later generations. We know full well that what we can see here are shades of what we can expect - and a far better job made of it - in Bleak House!

Is there more to Heep's repulsiveness than we are being told. Or is Dickens merely prejudiced as he reports from David's naive viewpoint? Why is it OK for (view spoiler) What's the difference? Is it just that Heep drops his aitches and is repulsive?

Is there more to Heep's repulsiveness than we are being told. Or is Dickens merely prejudiced as he reports from David's naive viewpoint? Why is it OK for (view spoiler) What's the difference? Is it just that Heep drops his aitches and is repulsive?Interestingly Uriah Heep may have had a form of dystonia,

"Dystonia is a neurological movement disorder in which sustained muscle contractions cause twisting and repetitive movements or abnormal postures ... Many sufferers have continuous pain, cramping, and relentless muscle spasms due to involuntary muscle movements. Other motor symptoms are possible including lip smacking."

I've now read chapter 37 and as I never fail to do every time I read this book, wanted to knock some sense into that little noodle Dora. I was struggling to remember which other character she reminded me of. In fact it was not in Dickens at all, but in Middlemarch by George Eliot... Dr Tertius Lydgate's wife Rosamond!

I've now read chapter 37 and as I never fail to do every time I read this book, wanted to knock some sense into that little noodle Dora. I was struggling to remember which other character she reminded me of. In fact it was not in Dickens at all, but in Middlemarch by George Eliot... Dr Tertius Lydgate's wife Rosamond! It looks very much as if Charles Dickens's model for the adorable Dora was his own wife, Kate, whom a friend of his described as,

"A pretty little woman, plump and fresh-coloured, with the large, heavy-lidded blue eyes so much admired by men. The nose was slightly retrousse, the forehead good, mouth small, round and red-lipped with a genial smiling expression of countenance, notwithstanding the sleepy look of the slow-moving eyes."

In Claire Tomalin's biography of Dickens, she wrote of Kate,

"She was not clever or accomplished like his sister Fanny and could never be his intellectual equal, which may have been part of her charm: foolish little women are more often presented as sexually desirable in his writing than clever, competent ones.... His decision to marry her was quickly made, and he never afterwards gave any account of what had led him to it, perhaps because he came to regard it as the worst mistake in his life."

and of course his subsequent (mis)treatment of his wife is very well documented. It's interesting to speculate on how besotted he may have been with her initially though, from these fanciful descriptions of (view spoiler)

Another parallel I could see here was Mr Dick's great literary enterprise of "the Memoir", and Dr Strong's of "the Dictionary". Both are absentminded characters; one far more eccentric than the other admittedly, but both being naive, gentle and kind.

Another parallel I could see here was Mr Dick's great literary enterprise of "the Memoir", and Dr Strong's of "the Dictionary". Both are absentminded characters; one far more eccentric than the other admittedly, but both being naive, gentle and kind. I'm now wondering if there's a prototype for this character in Dickens's own life. Perhaps again it was the kind schoolmaster he had when he was young.

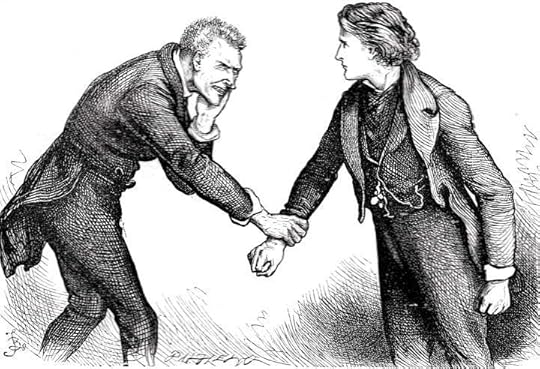

Events are moving on. I particularly like this illustration by Fred Barnard for Chapter 42 - you don't need me to tell you who it's of :)

Events are moving on. I particularly like this illustration by Fred Barnard for Chapter 42 - you don't need me to tell you who it's of :)

"He caught the hand in his, and we stood in that connection, looking at each other."

Dora:

Dora:

I came clean about my feelings about this little noodle earlier. She's perhaps the main character in Dickens whom he has (totally inadvertently) made many modern females dislike intensely, and I think is responsible for much of the misapprehension of those, who only have a smattering of familiarity with Charles Dickens, to think that he created "wishywashy heroines" despite all the evidence against this.

However, I shall try to think of why he wrote the character this way.

1. Clearly it's cathartic, because of his wife, as detailed in post 148. His own life reveals that he preferred this type of young pretty woman, and the disparity in marital relationships comes into his plots time and time again. (We even have it here with Dr Strong and Annie - although with a slight twist.)

2. Plot-wise, it does point up the fact of David's naivety quite well, and his self-absorption too. It also allows for the character of Agnes to be fully fleshed out by comparison.

3. I'm also interested in the sociological implications. I'm still cogitating on why it was OK for David to (view spoiler) - from both David's and Dora's points of view.

Class also comes in with Dora and Little Em'ly. Apart from money and education there seems to be little difference between Dora and Em'ly - and David was sweet on both of them.

4. So does this imply a mercenary instinct - whether overt or hidden? Even if you argue that it's just being financially practical (view spoiler) how can we then reconcile this with David's being besotted?

(I've always had difficulty too with Elizabeth Bennet's passion for Fitzwilliam Darcy seeming to date from the exact moment she had her first glimpse of Pemberley ...)

5. Dora is a-dora-ble to others too. They all seem to pet her all the time and generally treat her like a child (view spoiler). Aunt Betsey calls Dora "Little Blossom" and Dora makes "a rosebud of her mouth" during one of her many pouts. She doodles and does drawings of "little nosegays" and likenesses of Jip and David instead of figures and sums (view spoiler)

So all through this, Dickens is suggesting the childish, unformed nature of Dora. The Victorian ideal husband seemed to be one who could "form/mould" his wife through his greater experience and knowledge of the world. It comes into Victorian authors time and time again, and even a little earlier with Jane Austen.

Through the use of flower references to "Little Blossom" and "rosebud" he suggests innocent potential. Because she is a child, she does not realise any serious import, and her cookery-books etc are used for drawing in rather than recording recipes - and also, ridiculously, as a stool upon which Dora's dog can perform tricks.

6. Apparently a Victorian beauty ideal consisted in a woman being silly and insipid like Dora, or intelligent, calm and reliable like Agnes. We do need to be aware of his time, his focus, and the fact that he was writing in a world that could not even imagine what the 21st Century would be like; of what we now consider to be desirable, and how we should perceive and interact with one another.

I don't know if the similarity to Rosamond Lydgate in "Middlemarch" has struck anyone else. The pretty naive little wife, to be improved by her more experienced knowledgeable husband, is rather a mainstay of Victorian fiction I suppose.

I shall nevertheless be heartily relieved when (view spoiler)!

I'm now reading an interesting essay by John Sutherland about whether Miss Trotwood is technically a spinster :) John Forster always refers to the character as "Mrs Trotwood" and since he was privy to Charles Dickens's thoughts as he was writing David Copperfield, he should really know ...

I'm now reading an interesting essay by John Sutherland about whether Miss Trotwood is technically a spinster :) John Forster always refers to the character as "Mrs Trotwood" and since he was privy to Charles Dickens's thoughts as he was writing David Copperfield, he should really know ...But see comment 251.

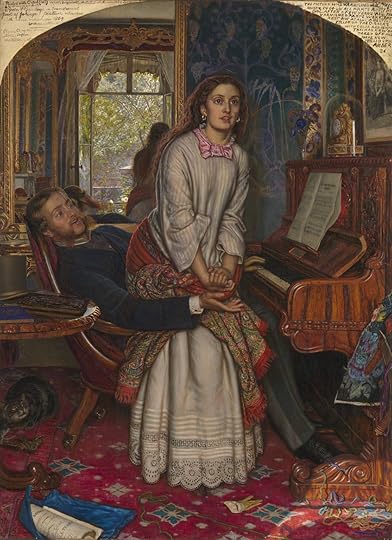

The plot has really moved along quite a lot! And another fact I'm finding fascinating, is that there's a connection with the Pre-Raphalites. Are they known outside this country I wonder.

The plot has really moved along quite a lot! And another fact I'm finding fascinating, is that there's a connection with the Pre-Raphalites. Are they known outside this country I wonder.A founding member was William Morris, who is quite famous world-wide I think, and another leading member of the movement was William Holman Hunt. He painted works such as "The Light of the World" - an image which is reproduced to be hung on Sunday Schools' walls throughout the country. We also see it on Christmas cards and bookmarks etc. It's probably his most famous work. Here it is:

Quite a lot of Pre-Raphaelite paintings are on permanent display at the Tate Britain Art Gallery, and one I know well from there by William Holman Hunt is called The Awakening Conscience. You can imagine how surprised I was to learn that the inspiration for this painting was none other than Little Em'ly from David Copperfield! Here is is:

Quite a lot of Pre-Raphaelite paintings are on permanent display at the Tate Britain Art Gallery, and one I know well from there by William Holman Hunt is called The Awakening Conscience. You can imagine how surprised I was to learn that the inspiration for this painting was none other than Little Em'ly from David Copperfield! Here is is:

Hunt had the idea while reading David Copperfield of making the conversion of a fallen woman a literal illustration of "The Light of the World." He was so deeply touched by (view spoiler) that he went exploring different haunts of "fallen girls" himself to find a suitable location to paint.

However, he decided not to illustrate any particular scene in the novel:

"While cogitating on the broad intention, I reflected that the instinctive eluding of pursuit by the erring one would not coincide with the willing conversion and instantaneous resolve for a higher life which it was necessary to emphasise".

He did not think it would be psychologically accurate, since he thought that such basic changes had to come from deep within one. He wanted to convey a specific moment - and also the idea that God works in mysterious ways.

What we see here is the irony of making (view spoiler)

In chapter 53, Dora's (view spoiler)

In chapter 53, Dora's (view spoiler)I suspect that Dickens has let his narrator-as-the-older-David mask slip a little here. What he puts in the mouth of Dora actually seems to be Dickens's own thoughts about the composite character he has created, by merging a depiction of his own real-life wife Kate, and his first love Maria Beadnell. I've described Kate before, so here's:

Maria Beadnell:

When Charles Dickens and Maria Beadnell first met in 1830, he fell madly in love with her. Much as we've read of David's mad passions and crushes on many young women, Charles's mind was quickly filled with romantic thoughts of everlasting love and marriage.

Maria's father was a banker, and neither of her parents approved of the relationship, considering Dickens to be too young and lacking in prospects to be considered suitable. It's unknown what Maria’s own feelings for Dickens were. Sometimes she seemed indifferent and sometimes encouraging. Perhaps she was a coquette. Later in life she claimed that she truly cared for him (but then by then of course he had become famous).

Apparently when Dickens became twenty one, in 1833, he threw himself a coming-of-age party, inviting the Beadnell family. During the evening Dickens took Maria aside, and admitted his feelings for her. However she insulted him and called him just a “boy”. Their relationship ended, and Maria Beadnell became Mrs. Henry Winter.

It would be good if the story ended there ... however, if you know the story of Little Dorrit, and the character of Flora Finching, you kind of know what happened to the two young sweethearts, Charles and Maria:

"Flora, always tall, had grown to be very broad too, and short of breath; but that was not much. Flora, whom he had left a lily, had become a peony; but that was not much. Flora, who had seemed enchanting in all she said and thought, was diffuse and silly. That was much. Flora, who had been spoiled and artless long ago, was determined to be spoiled and artless now. That was a fatal blow." – Little Dorrit

In real life, twenty-four years later Maria contacted Dickens, who was now a famous much-admired author. Despite the fact that they were both married to others, Dickens was thrilled to get her letter. It brought back memories of what he saw as his intense love for her (which looks very like a crush!) In 1855 they agreed to meet in secret, without their spouses. Maria warned Dickens that she was not the same young woman that he remembered.

Apparently he was surprised at the changes he saw. (Idiot!) And his appalled reaction resulted in the rather cruel portrayal of Flora Finching in Little Dorrit, based on Maria, as she now was. Maria pestered him, and the two met up once more for a dinner - but with their spouses. For ever after that, Dickens avoided Maria. Here she is:

Earlier I mentioned an interesting essay by John Sutherland about whether Miss Trotwood was technically a spinster. John Forster always refers to the character as "Mrs Trotwood" and since, as we know, he was privy to Charles Dickens's thoughts as he was writing David Copperfield, he should really know. Here is my review of the book, which contains several "literary conundrums".

Earlier I mentioned an interesting essay by John Sutherland about whether Miss Trotwood was technically a spinster. John Forster always refers to the character as "Mrs Trotwood" and since, as we know, he was privy to Charles Dickens's thoughts as he was writing David Copperfield, he should really know. Here is my review of the book, which contains several "literary conundrums". Now I've read chapter 54 again though, where Aunt Betsey "comes clean"to David, I really think I must add an edit to it! I don't get the impression that she is dissembling here, but that she is perfectly straightforward. And all the way through we've had this tempting thread of mystery dangled in front of us, and the explanation, when it comes, is really just a bit of a let-down. (I explain both John Sutherland 's theories and Charles Dickens's eventual explanation in the review itself, so won't repeat them here.)

It seems more likely to me than anything, that Aunt Betsey's husband was a sort of potential back-up plot. He was a flexible non-character who could be expanded as Dickens saw fit- or treated as a loose end which he could just tie up - as he has done.

Dickens seemed to like to leave himself a bit of "wiggle room" :D

Books mentioned in this topic

Our Mutual Friend (other topics)Nicholas Nickleby (other topics)

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (other topics)

Bleak House (other topics)

The Pickwick Papers (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

Charles Dickens (other topics)Anne Brontë (other topics)

Henry Mayhew (other topics)

Harland S. Nelson (other topics)

John Forster (other topics)

More...

At the moment we haven't heard of Edith for a couple of chapters (view spoiler)[since she disappeared with Carker, and although we have been told via Rob the Grinder that they go to Dijon, I haven't a clue how this will turn out. When she first ran away, I thought of it as less an escape than an act of wilful self-destruction. (hide spoiler)] There's a parallel to that in the later Bleak House.

I've read Dombey and Son before - and also seen and heard dramatisations, but can't remember any of the current events! And I find that I've mixed up Dombey with Ralph Nickleby, so am not even sure of his demise - or if he has one! Though it would be very unlike Dickens to not provide us with a happy ending - or justice of sorts, wouldn't it?

(view spoiler)[So that would fit in with my assumption that the passages where Edith seem scared of Carker are more that Dickens is using Edith to show just how threatening and manipulative Carker is. It's with her that Carker is at his most oily and two-faced, I think. He gets across the message that he is all-powerful, that he is appearing to be "Dombey's man" through and through, he actually is there if she ever needs assistance. But Carker also conveys subtly that this could change at a moment's notice. He's completely duplicitous, and this unnerves her. He's much more clever and cunning than Dombey and we get the feeling that he knows exactly how much of a front Edith's haughty behaviour is, whereas Dombey hasn't a clue, and just sees it as what he would expect from his wife - except towards himself, towards whom he insists on respect and total obedience.

Carker is a puppet-master - or thinks he is, although with appearance in chapter 53 of another character, I'm not so sure. (hide spoiler)] And I think I'll need to see Edith's bearing in the last few chapters to see how inwardly strong she is after all - or even if she survives.

I was reading chapter 54 earlier on, and it suddenly struck me that it was far more exciting than anything in the Stephen King book I've just finished :)