The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Martin Chuzzlewit

Martin Chuzzlewit

>

MC, Chp. 33-35

Chapter 34

This is yet another chapter whose welcome is outstayed from ist very beginning, I’d say, because considering its importance for the story, it is rather long. Our chapter describes how Martin and Mark travel back from Eden to New York on board a steamboat. Even after all the encounters our friends and we have gone through, the narrator refuses to let the two men pursue their way in silence and without disturbance, but he has to throw another of those satirical characters into their way. This time, it is a philosophic man called Elijah Pogram, who is both rather scruffy in appearance and a Member of Congress. Again, this man enters into a conversation about the eternal question “How do you like our country?“ and although Martin says,

“‘I have learend by experience, that you take an unfair advantage of a stranger, when you ask that question. You don’t mean it to be answered, except in one way. Now, I don’t choose to answer it in that way, for I cannot honestly answer it in that way. And therefore, I would rather not answer it at all.‘“,

the usual conversation is renewed. The venerable Elijah Pogram sings a hymn of his country, accusing Martin of irrational hatred, and Martin tries to voice his criticism, e.g. of people like Mr. Chollop, who think they can settle any problem with a bowie-knife or a gun. To top it all, the company Martin enjoys on board that ship is eventually completed by Mrs. Hominy and some other literary ladies. There is a lot of talk going on, but the only funny situation for me arises when one of the ladies, obviously a transcendentalist, speaks in the manner of the lofty Emerson:

“‘Mind and matter […] glide swift into the vortex of immensity. Howls the sublime, and softly sleeps the calm Ideal, in the whispering chmabers of Imagination. To hear it, sweet it is. But then, outlaughs the stern philosopher, and saith to the Grotesque, ‘What ho! Arrest for me that Agency. Go, bring it here!‘ And so the vision fadeth.‘“

I had to read Emerson at my university, and that is exactly what it sounded like. Dickens as a master-imitator of life, or whatever.

When our friends arrive in New York, they settle their affairs with Mr. Bevan, and due to his previous good offices on board the Screw, Mark is offered the job as a cook on the voyage back to Europe. Once again, it is Mark’s uncalculating helpfulness that have helped him and Martin on their way.

The American experiences are summarized like this at the end of the chapter:

“‘Why, I was a–thinking, sir,’ returned Mark, ‘that if I was a painter and was called upon to paint the American Eagle, how should I do it?’

‘Paint it as like an Eagle as you could, I suppose.’

‘No,’ said Mark. ‘That wouldn’t do for me, sir. I should want to draw it like a Bat, for its short–sightedness; like a Bantam, for its bragging; like a Magpie, for its honesty; like a Peacock, for its vanity; like a ostrich, for its putting its head in the mud, and thinking nobody sees it —’

‘And like a Phoenix, for its power of springing from the ashes of its faults and vices, and soaring up anew into the sky!’ said Martin. ‘Well, Mark. Let us hope so.’“

QUESTIONS

What do you think about this chapter? Was it necessary, is it interesting, funny?

What do the last words between Mark and Martin on the subject of their American impressions suggest? Do they in any way mitigate the scathing criticism characteristic of the American episodes?

This is yet another chapter whose welcome is outstayed from ist very beginning, I’d say, because considering its importance for the story, it is rather long. Our chapter describes how Martin and Mark travel back from Eden to New York on board a steamboat. Even after all the encounters our friends and we have gone through, the narrator refuses to let the two men pursue their way in silence and without disturbance, but he has to throw another of those satirical characters into their way. This time, it is a philosophic man called Elijah Pogram, who is both rather scruffy in appearance and a Member of Congress. Again, this man enters into a conversation about the eternal question “How do you like our country?“ and although Martin says,

“‘I have learend by experience, that you take an unfair advantage of a stranger, when you ask that question. You don’t mean it to be answered, except in one way. Now, I don’t choose to answer it in that way, for I cannot honestly answer it in that way. And therefore, I would rather not answer it at all.‘“,

the usual conversation is renewed. The venerable Elijah Pogram sings a hymn of his country, accusing Martin of irrational hatred, and Martin tries to voice his criticism, e.g. of people like Mr. Chollop, who think they can settle any problem with a bowie-knife or a gun. To top it all, the company Martin enjoys on board that ship is eventually completed by Mrs. Hominy and some other literary ladies. There is a lot of talk going on, but the only funny situation for me arises when one of the ladies, obviously a transcendentalist, speaks in the manner of the lofty Emerson:

“‘Mind and matter […] glide swift into the vortex of immensity. Howls the sublime, and softly sleeps the calm Ideal, in the whispering chmabers of Imagination. To hear it, sweet it is. But then, outlaughs the stern philosopher, and saith to the Grotesque, ‘What ho! Arrest for me that Agency. Go, bring it here!‘ And so the vision fadeth.‘“

I had to read Emerson at my university, and that is exactly what it sounded like. Dickens as a master-imitator of life, or whatever.

When our friends arrive in New York, they settle their affairs with Mr. Bevan, and due to his previous good offices on board the Screw, Mark is offered the job as a cook on the voyage back to Europe. Once again, it is Mark’s uncalculating helpfulness that have helped him and Martin on their way.

The American experiences are summarized like this at the end of the chapter:

“‘Why, I was a–thinking, sir,’ returned Mark, ‘that if I was a painter and was called upon to paint the American Eagle, how should I do it?’

‘Paint it as like an Eagle as you could, I suppose.’

‘No,’ said Mark. ‘That wouldn’t do for me, sir. I should want to draw it like a Bat, for its short–sightedness; like a Bantam, for its bragging; like a Magpie, for its honesty; like a Peacock, for its vanity; like a ostrich, for its putting its head in the mud, and thinking nobody sees it —’

‘And like a Phoenix, for its power of springing from the ashes of its faults and vices, and soaring up anew into the sky!’ said Martin. ‘Well, Mark. Let us hope so.’“

QUESTIONS

What do you think about this chapter? Was it necessary, is it interesting, funny?

What do the last words between Mark and Martin on the subject of their American impressions suggest? Do they in any way mitigate the scathing criticism characteristic of the American episodes?

Chapter 35

Lo! our friends have finally arrived home, and we have every reason to hope that there will be no more repetitive descriptions of Martin meeting people who chew tobacco and quarrel with him about the respective merits or demerits of the Old World and the New. Let’s also hope that Martin is going to interact more with his grandfather and with Pecksniff, the Serpent!

Arriving in port, our friends experience the typical feeling you have when returning home from long absence – everything seems brighter and more beautiful than it did when you left. Our narrator states that it has been a year since Martin and Mark embarked for the U.S., and now

”[i]n health and fortune, prospect and resource, they came back poorer men than they had gone. away. But it was home.”

Basically, Martin’s American adventure would be regarded as an utter humiliation and an error by the eyes of the world, most certainly by Jonas Chuzzlewit and other eminent members of that family. Plus, they step ashore without any concrete idea as to what to do with their future and as to what strategy to employ with regard to Mary and old Mr. Chuzzlewit. – And yet, was Martin’s excursion entirely futile?

When they step into a tavern to refresh themselves – the narrator, in order to give an impression of the place’s quaintness and nookiness, uses the memorable expression ”It had more corners in it that the brain of an obstinate man” –, they discuss their future course of action and decide it would be best to walk to the Dragon and let themselves be filled in by Mrs. Lupin, and later by Tom (for they don’t know, of course, that Tom no longer is an inmate of Mr. Pecksniff’s household). Suddenly see Mr. Pecksniff walk down the street outside, and people turn their heads after him to get a good glimpse of that walking spectacle. Inquiring about the man they have just seen pass, they are informed that this is Mr. Pecksniff, the celebrated architect, who has come to witness a Member of Parliament lay the first stone of a new public building he designed. As the ceremony is going to take place this very day, Martin and Mark make up their minds to go and see it, an idea that has occurred to lots of other people, though, so that they have to fight their way through a crowd, which is advantageous in that Mr. Pecksniff does not spot them among the onlookers. During the ceremony, Mr. Pecksniff unrolls the plans for the building, and Martin, to his dismay and to his wrath, notices that the plans were the ones he drew before he left Mr. Pecksniff’s house a year ago, and that Mr. Pecksniff has simply added some windows, thus – as Martin thinks – spoiling the overall impression of the building. The Member of Parliament, in his speech, praises Mr. Pecksniff and expresses his hopes that in future their mutual relationship will be a close and fulfilling one, and Mr. Pecksniff has yet another opportunity to show his modesty and his sentiment.

Mark tries to cheer Martin up by saying,

”’Lord bless you, sir! […] what’s the use? Some architects are clever at making foundations, and some architects are clever at building on ‘em when they’re made. But it’ll all come right in the end, sir; it’ll all come right!’”

The new Martin, instead of remaining sullen and vindictive, admits that Mark is ”’the bet master in the world’” and that he will try to learn from Mark’s example and advice.

QUESTIONS

This is another of Dickens’s coincidences: The two men coming back from America and happen, on that very day and in that very place, to run into Pecksniff, who is about to cash in, both materially and socially, on an idea developed by Martin. In what way can this incident be taken as foreshadowing some evil? What does Martin’s reaction to Mark’s words show about his own development and that of their relationship?

Pecksniff seems at the height of his success. Are there any signs of his stroke of luck running out?

Lo! our friends have finally arrived home, and we have every reason to hope that there will be no more repetitive descriptions of Martin meeting people who chew tobacco and quarrel with him about the respective merits or demerits of the Old World and the New. Let’s also hope that Martin is going to interact more with his grandfather and with Pecksniff, the Serpent!

Arriving in port, our friends experience the typical feeling you have when returning home from long absence – everything seems brighter and more beautiful than it did when you left. Our narrator states that it has been a year since Martin and Mark embarked for the U.S., and now

”[i]n health and fortune, prospect and resource, they came back poorer men than they had gone. away. But it was home.”

Basically, Martin’s American adventure would be regarded as an utter humiliation and an error by the eyes of the world, most certainly by Jonas Chuzzlewit and other eminent members of that family. Plus, they step ashore without any concrete idea as to what to do with their future and as to what strategy to employ with regard to Mary and old Mr. Chuzzlewit. – And yet, was Martin’s excursion entirely futile?

When they step into a tavern to refresh themselves – the narrator, in order to give an impression of the place’s quaintness and nookiness, uses the memorable expression ”It had more corners in it that the brain of an obstinate man” –, they discuss their future course of action and decide it would be best to walk to the Dragon and let themselves be filled in by Mrs. Lupin, and later by Tom (for they don’t know, of course, that Tom no longer is an inmate of Mr. Pecksniff’s household). Suddenly see Mr. Pecksniff walk down the street outside, and people turn their heads after him to get a good glimpse of that walking spectacle. Inquiring about the man they have just seen pass, they are informed that this is Mr. Pecksniff, the celebrated architect, who has come to witness a Member of Parliament lay the first stone of a new public building he designed. As the ceremony is going to take place this very day, Martin and Mark make up their minds to go and see it, an idea that has occurred to lots of other people, though, so that they have to fight their way through a crowd, which is advantageous in that Mr. Pecksniff does not spot them among the onlookers. During the ceremony, Mr. Pecksniff unrolls the plans for the building, and Martin, to his dismay and to his wrath, notices that the plans were the ones he drew before he left Mr. Pecksniff’s house a year ago, and that Mr. Pecksniff has simply added some windows, thus – as Martin thinks – spoiling the overall impression of the building. The Member of Parliament, in his speech, praises Mr. Pecksniff and expresses his hopes that in future their mutual relationship will be a close and fulfilling one, and Mr. Pecksniff has yet another opportunity to show his modesty and his sentiment.

Mark tries to cheer Martin up by saying,

”’Lord bless you, sir! […] what’s the use? Some architects are clever at making foundations, and some architects are clever at building on ‘em when they’re made. But it’ll all come right in the end, sir; it’ll all come right!’”

The new Martin, instead of remaining sullen and vindictive, admits that Mark is ”’the bet master in the world’” and that he will try to learn from Mark’s example and advice.

QUESTIONS

This is another of Dickens’s coincidences: The two men coming back from America and happen, on that very day and in that very place, to run into Pecksniff, who is about to cash in, both materially and socially, on an idea developed by Martin. In what way can this incident be taken as foreshadowing some evil? What does Martin’s reaction to Mark’s words show about his own development and that of their relationship?

Pecksniff seems at the height of his success. Are there any signs of his stroke of luck running out?

Tristram wrote: "Hello Fellow Curiosities,

This week, at last, we will see our friends return to Merry Olde England, which is good for the novel as such since it needs no longer stand like the Colossus of Rhodes, w..."

Tristram

You ask such good questions. This chapter is certainly a pivotal one. Martin is finally awakening from his self-serving slumber, Mark’s presence and positive attitude is given a wider context and focus and some interesting links, comparisons and contrasts between Martin and Tom are evolving. Slowly but surely the novel is beginning to braid itself together. And yes, by bringing Mark and Martin back to England Dickens is repairing the awkwardness of a tale of two countries.

The concept of Manifest Destiny was still in its infant stages of definition and creation in the 1840’s but the character of Chollop with his Bowie-knife, guns and attitude may be Dickens’s way of personifying the idea.

This week, at last, we will see our friends return to Merry Olde England, which is good for the novel as such since it needs no longer stand like the Colossus of Rhodes, w..."

Tristram

You ask such good questions. This chapter is certainly a pivotal one. Martin is finally awakening from his self-serving slumber, Mark’s presence and positive attitude is given a wider context and focus and some interesting links, comparisons and contrasts between Martin and Tom are evolving. Slowly but surely the novel is beginning to braid itself together. And yes, by bringing Mark and Martin back to England Dickens is repairing the awkwardness of a tale of two countries.

The concept of Manifest Destiny was still in its infant stages of definition and creation in the 1840’s but the character of Chollop with his Bowie-knife, guns and attitude may be Dickens’s way of personifying the idea.

Martin’s conversion of character and nature to one who is much more understanding and aware of others may seem remarkably quick but I was not disturbed by it at all. The disappointments he found in America were needed for him to better understand what he left, ignored or took for granted in England. Helped towards a better understanding of himself by those around him ( both good and bad), guided to a revised way of perceiving the world by Mark, and having experienced the fact that what one thought would be an Eden is, in reality, much less positive, he is ready to experience a rebirth in England.

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 35

Lo! our friends have finally arrived home, and we have every reason to hope that there will be no more repetitive descriptions of Martin meeting people who chew tobacco and quarrel with..."

Martin and Mark’s return to England and their being immediately plunged into Pecksniff’s world of lies and false nature is a perfect plot setting. Martin has learned much about himself in his trip to Eden with Mark. On the other hand, Pecksniff has learned nothing about himself as he continues to be self-centred and passively arrogant. In the past year Pecksniff has alienated or lost everyone from his home. The exception is, of course, Chuzzlewit senior and the rather captive Mary. We know that Dickens has established that Pecksniff is like a snake in a garden. He has tempted Mary, he has bit her finger, and he is the ultimate deceiver.

Now we have Martin junior returned from a place called Eden. Martin and the reader know that what Pecksniff claims to be his architectural creation is, in fact, Martin junior’s. Dickens has now set up a situation where Martin junior may bring his father to see his changed self, a place where Martin can protect and perhaps marry Mary and build his own character in such a matter that he can establish why the novel bears his name.

Lo! our friends have finally arrived home, and we have every reason to hope that there will be no more repetitive descriptions of Martin meeting people who chew tobacco and quarrel with..."

Martin and Mark’s return to England and their being immediately plunged into Pecksniff’s world of lies and false nature is a perfect plot setting. Martin has learned much about himself in his trip to Eden with Mark. On the other hand, Pecksniff has learned nothing about himself as he continues to be self-centred and passively arrogant. In the past year Pecksniff has alienated or lost everyone from his home. The exception is, of course, Chuzzlewit senior and the rather captive Mary. We know that Dickens has established that Pecksniff is like a snake in a garden. He has tempted Mary, he has bit her finger, and he is the ultimate deceiver.

Now we have Martin junior returned from a place called Eden. Martin and the reader know that what Pecksniff claims to be his architectural creation is, in fact, Martin junior’s. Dickens has now set up a situation where Martin junior may bring his father to see his changed self, a place where Martin can protect and perhaps marry Mary and build his own character in such a matter that he can establish why the novel bears his name.

I had expected Martin Jr's change to happen when he fell ill himself, and was a bit surprised it happend when Mark fell ill. It did fit though, and might also show that the change was not as abrupt as it seemed. Martin did not act kinder after after people took care of him, he became kinder when he finally connected the dots he had been seeing all along.

I found chapter 34 funnier and easier to read than other American chapters, probably because I knew they were going back to England, and there would not be dozens of the same kind of chapter waiting for me ;-) It was more of the same though, without giving much character development, so it did seem a bit useless. Funny, but not adding anything else. The last bit, about how to paint the eagle, could have been added to one of the other chapters.

Ah yes, Pecksniff did not change a bit, did he? Another great example of Dickensian chance of luck, indeed. I agree that it worked it's way of comparing and contrasting Pecksniff and Martin Jr. very well though. I also love the way places like that inn are described, especially at this time of year, when I want to curl up in a small room full of nooks and crannies myself, surrounded by warmth, someone I care about and good food.

I found chapter 34 funnier and easier to read than other American chapters, probably because I knew they were going back to England, and there would not be dozens of the same kind of chapter waiting for me ;-) It was more of the same though, without giving much character development, so it did seem a bit useless. Funny, but not adding anything else. The last bit, about how to paint the eagle, could have been added to one of the other chapters.

Ah yes, Pecksniff did not change a bit, did he? Another great example of Dickensian chance of luck, indeed. I agree that it worked it's way of comparing and contrasting Pecksniff and Martin Jr. very well though. I also love the way places like that inn are described, especially at this time of year, when I want to curl up in a small room full of nooks and crannies myself, surrounded by warmth, someone I care about and good food.

Tristram wrote: "Hello Fellow Curiosities,

This week, at last, we will see our friends return to Merry Olde England, which is good for the novel as such since it needs no longer stand like the Colossus of Rhodes, w..."

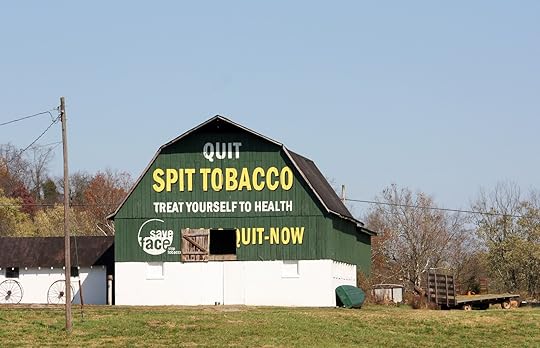

Before we leave America for good I have a story you must hear because I had to experience it. I have a feeling I told it before, so sorry to anyone who has heard it.

Dickens hated the practice of chewing tobacco and spitting in America. Me too, I hate it more than he ever could have. Why you ask? (I know you did). Not only do I despise trying to eat in a restaurant when someone near you is spitting into a cup he has brought along for the occasion, I have an even better reason.

When I was about 14 years old we had a "Valentine's Day" party for the youth group at our church of all places. People are always amazed that we had a Valentine's party in a church of all places. We hung up red and white streamers, cut out hearts from red paper and taped them to the wall, all those Valentine looking things, then we danced, played games, etc. One of the games we played was "Spin the Bottle", which thinking back on this now even I think it was a surprising game to be playing at a church youth activity, but nevertheless we played. I don't remember who spun the bottle, but I ended up having to kiss a boy about the same age as I was who I found out had a wad or whatever it's called, of chewing tobacco in his mouth. It was the most disgusting thing I ever tasted and I never again played spin the bottle. I still get nauseous just thinking of it.

The other "highlight" of the night was another boy that I knew begged me into to go into the kitchen of the church with him and asked me to teach him how to kiss before we started the game, he had never kissed a girl before, and didn't want embarrass himself in front of everyone. So he and I briefly kissed in the kitchen, although I am absolutely sure I had never kissed anyone before either and he wouldn't have been my first choice, he just picked me because we grew up next door to each other. The thing about this story that amuses people now is that this boy ended up being gay and as far as I know is living happily with the man he loves. My kids say kissing me is what did it. :-)

This week, at last, we will see our friends return to Merry Olde England, which is good for the novel as such since it needs no longer stand like the Colossus of Rhodes, w..."

Before we leave America for good I have a story you must hear because I had to experience it. I have a feeling I told it before, so sorry to anyone who has heard it.

Dickens hated the practice of chewing tobacco and spitting in America. Me too, I hate it more than he ever could have. Why you ask? (I know you did). Not only do I despise trying to eat in a restaurant when someone near you is spitting into a cup he has brought along for the occasion, I have an even better reason.

When I was about 14 years old we had a "Valentine's Day" party for the youth group at our church of all places. People are always amazed that we had a Valentine's party in a church of all places. We hung up red and white streamers, cut out hearts from red paper and taped them to the wall, all those Valentine looking things, then we danced, played games, etc. One of the games we played was "Spin the Bottle", which thinking back on this now even I think it was a surprising game to be playing at a church youth activity, but nevertheless we played. I don't remember who spun the bottle, but I ended up having to kiss a boy about the same age as I was who I found out had a wad or whatever it's called, of chewing tobacco in his mouth. It was the most disgusting thing I ever tasted and I never again played spin the bottle. I still get nauseous just thinking of it.

The other "highlight" of the night was another boy that I knew begged me into to go into the kitchen of the church with him and asked me to teach him how to kiss before we started the game, he had never kissed a girl before, and didn't want embarrass himself in front of everyone. So he and I briefly kissed in the kitchen, although I am absolutely sure I had never kissed anyone before either and he wouldn't have been my first choice, he just picked me because we grew up next door to each other. The thing about this story that amuses people now is that this boy ended up being gay and as far as I know is living happily with the man he loves. My kids say kissing me is what did it. :-)

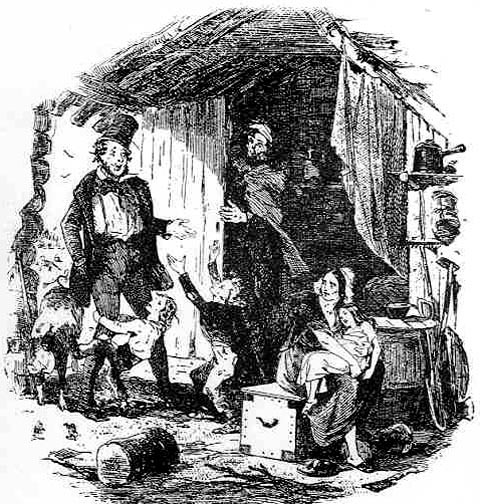

Mr. Tapley is Recognised by Some Fellow-Citizens of Eden

Chapter 33

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

He went up to the nearest cabin, and knocked with his hand. Being desired to enter, he complied.

"Neighbour," said Mark; "for I am a neighbour, though you don't know me; I've come a-begging. Hallo! hal—lo! Am I a-bed, and dreaming!"

He made this exclamation on hearing his own name pronounced, and finding himself clasped about the skirts by two little boys, whose faces he had often washed, and whose suppers he had often cooked, on board of that noble and fast-sailing line-of-packet ship, the Screw.

"My eyes is wrong!" said Mark. "I don’t believe ‘em. That ain’t my fellow-passenger younder, a-nursing her little girl, who, I am sorry to see, is so delicate; and that ain’t her husband as come to New York to fetch her. Nor these," he added, looking down upon the boys, "ain’t them two young shavers as was so familiar to me; though they are uncommon like ‘em. That I must confess."

Commentary:

In American Notes, a woman travelling on the steamboat with her new-born infant is happily re-united with her husband, who has never seen the child, born while his wife was in New York. In contrast, in Martin Chuzzlewit, the young woman and her children from steerage find her husband worn out by the hellish heat and disease of the Mississippi at Eden, a cautionary tale for would-be English emigrants. — "America's Eden".

By the time that Chapman and Hall had published Chapter 33 in Part XIII of Martin Chuzzlewit, a great event in the history of English literature and Victorian publishing had transpired: Chapman and Hall's issuing the first and most famous of the Christmas Books, A Christmas Carol, in December 1843. In that celebrated yuletide novella, Dickens contrasts the jollity and abundance of the season which the upper-middle class enjoy with the privations of the poor and the terrors of the future which confront the misanthropic, self-centred Ebenezer Scrooge. In this final American scene by Phiz, we observe a similar contrast, with the jovial Mark Tapley, despite the tribulations of Eden, standing in for the Spirit of Christmas Present and the suffering colonist family from The Screw standing in for the ever-jovial Cratchits. Like that cheerful family, they are happy just to be in each other's company — and like them they are about to lose their youngest child. Ironically, Dickens may have based the immigrant family upon the reunion of a young husband and wife that he witnessed aboard a steamboat at St. Louis during his 1842 tour, a far more positive, upbeat moment than that which Phiz has depicted in Mr. Tapley is Recognised by Some Fellow-Citizens of Eden. Here, the immigrant wife holds the dying child on her lap as the ebullient Mark Tapley enters the squalid log-cabin. In contrast to Phiz's ragged immigrant couple, Marcus Stone's husband and wife in his realisation of "The Little Wife" in American Notes for General Circulation (1842) are substantial, well-dressed figures whose health and prosperity betoken a bright future in America.

Although it is hardly the exposé of the appalling conditions endured by English immigrants that Dickens delivers, Phiz's twenty-fifth illustration for Martin Chuzzlewit shows us those squalid quarters, with rough shelves and flour cask in the corner, as described by Dickens. The artist, however, focuses our attentions on the ever-cheerful Mark and the "young shavers" who respond with undiluted joy to Mark's sudden arrival in their unhealthy cabin, as Mark unexpectedly renews his acquaintance with his fellow passengers from steerage. Mark has just announced himself their "neighbour," and has just recognized them as the boys in glee hug his legs. As yet, the wraith-like, ill-kempt, and ill-clad father has yet to respond as he holds the door. This is therefore not a true tableau or moment of stasis, but rather a snapshot catching its figures in the midst of action: shortly the mother (decorously holding rather than "nursing" the sick child on her lap) will be overwhelmed by tears of gladness. In the illustration, we do not have a real sense of the feverous child's perilous state of health, but the text makes clear that the fate of the youngest member of the little family apparently foreshadows similar tribulation for the named partner of Chuzzlewit and Co.

"Jolly!"

Chapter 33

Fred Barnard

A suitably purgatorial experience for gullible immigrants; the faithful Mark tends a feverish Martin in their cabin in Eden, in the swamps of the Mississippi Valley.

Text Illustrated:

Martin indeed was dangerously ill; very near his death. He lay in that state many days, during which time Mark’s poor friends, regardless of themselves, attended him. Mark, fatigued in mind and body; working all the day and sitting up at night; worn with hard living and the unaccustomed toil of his new life; surrounded by dismal and discouraging circumstances of every kind; never complained or yielded in the least degree. If ever he had thought Martin selfish or inconsiderate, or had deemed him energetic only by fits and starts, and then too passive for their desperate fortunes, he now forgot it all. He remembered nothing but the better qualities of his fellow-wanderer, and was devoted to him, heart and hand.

Hannibal Chollop

Chapter 33

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

Commentary:

Although Barnard in the next decade chose to depict one of young Martin's more benign American acquaintances, the proprietor of the National Hotel, Captain Kedgick, he seems to have thought many of the most remarkable people in the country too grotesque even for his pen — too hyperbolical or exaggerated for a social realist. Eytinge, a Yankee and moreover an Easterner, must have eyed such denizens of the frontier as the diamond in the rough, Major Hannibal Chollop, with more than a little scorn as the knife-wielding, pistol- packing "Major" is a staunch defender of the institutions of slavery and lynching. By implication contrasting this American original with the New England sophisticate Mr. Bevan, Dickens paints an extensive portrait of the raw frontiersman in chapter 33, when he visits Mark and Martin at their cabin in the swamp of Eden on the shores of the Mississippi:

"There's one good thing in this place, sir," said Mr. Tapley, scrubbing away at the linen, "as disposes me to be jolly; and that is that it's a reg'lar little United States in itself. There's two or three American settlers left; and they coolly comes over one, even here, sir, as if it was the wholesomest and loveliest spot in the world. But they're like the cock that went and hid himself to save his life, and was found out by the noise he made. They can't help crowing. They was born to do it, and do it they must, whatever comes of it."

Glancing from his work out at the door as he said these words, Mark's eyes encountered a lean person in a blue frock and a straw hat, with a short black pipe in his mouth, and a great hickory stick studded all over with knots, in his hand; who smoking and chewing as he came along, and spitting frequently, recorded his progress by a train of decomposed tobacco on the ground. "Here's one on 'em," cried Mark, "Hannibal Chollop."

"Don't let him in," said Martin, feebly.

"He won't want any letting in," replied Mark. "He'll come in, sir." Which turned out to be quite true, for he did. His face was almost as hard and knobby as his stick; and so were his hands. His head was like an old black hearth-broom. He sat down on the chest with his hat on; and crossing his legs and looking up at Mark, said, without removing his pipe, —

"Well, Mr. Co.! and how do you git along, sir?"

It may be necessary to observe that Mr. Tapley had gravely introduced himself to all strangers, by that name.

"Pretty well, sir; pretty well," said Mark.

"If this ain't Mr. Chuzzlewit, ain't it!" exclaimed the visitor. "How do you git along, sir?"

Martin shook his head, and drew the blanket over it involuntarily; for he felt that Hannibal was going to spit; and his eye, as the song says, was upon him.

"You need not regard me, sir," observed Mr. Chollop, complacently. "I am fever-proof, and likewise agur."

"Mine was a more selfish motive," said Martin, looking out again. "I was afraid you were going to —"

"I can calc'late my distance, sir," returned Mr. Chollop, "to an inch."

With a proof of which happy faculty he immediately favoured him. "I re-quire, sir," said Hannibal, "two foot clear in a circ'lar di-rection, and can engage my-self toe keep within it. I have gone ten foot, in a circ'lar di-rection, but that was for a wager."

"I hope you won it, sir," said Mark. "Well, sir, I realised the stakes," said Chollop. "Yes, sir."

He was silent for a time, during which he was actively engaged in the formation of a magic circle round the chest on which he sat. When it was completed, he began to talk again.

"How do you like our country, sir?" he inquired, looking at Martin.

"Not at all," was the invalid's reply.

Chollop continued to smoke without the least appearance of emotion, until he felt disposed to speak again. That time at length arriving, he took his pipe from his mouth, and said: —

"I am not surprised to hear you say so. It re-quires An elevation, and A preparation of the intellect. The mind of man must be prepared for Freedom, Mr. Co."

He addressed himself to Mark; because he saw that Martin, who wished him to go, being already half-mad with feverish irritation, which the droning voice of this new horror rendered almost insupportable, had closed his eyes, and turned on his uneasy bed.

"A little bodily preparation wouldn't be amiss, either, would it, sir," said Mark, "in the case of a blessed old swamp like this?"

"Do you con-sider this a swamp, sir?" inquired Chollop gravely.

"Why yes, sir," returned Mark. "I haven't a doubt about it myself."

"The sentiment is quite Europian," said the major, "and does not surprise me; what would your English millions say to such a swamp in England, sir?"

"They'd say it was an uncommon nasty one, I should think, said Mark; "and that they would rather be inoculated for fever in some other way."

Europian!" remarked Chollop, with sardonic pity. "Quite Europian!"

And there he sat. Silent and cool, as if the house were his; smoking away like a factory chimney.

Mr. Chollop was, of course, one of the most remarkable men in the country; but he really was a notorious person besides. He was usually described by his friends, in the South and West, as "a splendid sample of our na-tive raw material, sir," and was much esteemed for his devotion to rational Liberty; for the better propagation whereof he usually carried a brace of revolving pistols in his coat pocket, with seven barrels a-piece. He also carried, amongst other trinkets, a sword-stick, which he called his "Tickler"; and a great knife, which (for he was a man of a pleasant turn of humour) he called "Ripper," in allusion to its usefulness as a means of ventilating the stomach of any adversary in a close contest. He had used these weapons with distinguished effect in several instances, all duly chronicled in the newspapers; and was greatly beloved for the gallant manner in which he had "jobbed out" the eye of one gentleman, as he was in the act of knocking at his own street-door.

Mr. Chollop was a man of a roving disposition; and, in any less advanced community, might have been mistaken for a violent vagabond. But his fine qualities being perfectly understood and appreciated in those regions where his lot was cast, and where he had many kindred spirits to consort with, he may be regarded as having been born under a fortunate star, which is not always the case with a man so much before the age in which he lives. Preferring, with a view to the gratification of his tickling and ripping fancies, to dwell upon the outskirts of society, and in the more remote towns and cities, he was in the habit of emigrating from place to place, and establishing in each some business — usually a newspaper — which he presently sold; for the most part closing the bargain by challenging, stabbing, pistolling, or gouging the new editor, before he had quite taken possession of the property.

He had come to Eden on a speculation of this kind, but had abandoned it, and was about to leave. He always introduced himself to strangers as a worshipper of Freedom; was the consistent advocate of Lynch law, and slavery; and invariably recommended, both in print and speech, the "tarring and feathering" of any unpopular person who differed from himself. He called this "planting the standard of civilization in the wilder gardens of My country."

There is little doubt that Chollop would have planted this standard in Eden at Mark's expense, in return for his plainness of speech (for the genuine Freedom is dumb, save when she vaunts herself), but for the utter desolation and decay prevailing in the settlement, and his own approaching departure from it. As it was, he contented himself with showing Mark one of the revolving-pistols, and asking him what he thought of that weapon.

"It ain't long since I shot a man down with that, sir, in the State of Illinoy," observed Chollop.

"Did you, indeed!" said Mark, without the smallest agitation. "Very free of you. And very independent!"

"I shot him down, sir," pursued Chollop, "for asserting in the Spartan Portico, a tri-weekly journal, that the ancient Athenians went a-head of the present Locofoco Ticket."

"And what's that?" asked Mark. "Europian not to know," said Chollop, smoking placidly. "Europian quite!"

Appropriately, Phiz neglected such Dickensian whimsies in favor of a scene between the indefatigable Mark and the desperate neighbors laid low by hunger and fever in "Mr. Tapley is Recognized by Some Fellow-Citizens of Eden" (January 1844), maintaining the focus on the moral development of the young Englishmen abroad in a slough of despond. However, re-illustrating the novel from a Northerner's perspective just after the conclusion of the Civil War, Eytinge cannot resist the temptation to pillory Major Chollop and the "smart behaviour" of the western frontier, where "revolving-pistols" serve as the final arbiter of all human disputes. Eytinge has deliberately posed the Major in front of a swamp scene of desolation, for he is a figure in no way connected to the civilization of the East. Chollop is characterised by his straw hat, corncob pipe, ill-kempt hairstyle and beard, and most significantly by the revolver in his belt and his sword-cane. In the ensuing debate between Old World and New World values which immediately precedes the woodcut of the Major, one cannot resist siding with Martin against the advocate of slavery and enemy of the rule of law.

Mr. Chollop Visits Martin

Chapter 33

Harry Furniss

Here, self-styled architect Martin Chuzzlewit of Chuzzlewit & Co., Eden, receives a personal call from the rough-and-ready frontiersman, the Bowie-knife-wielding Hannibal Chollop. The delirious Martin,however, is not up to much conversation as he recovers from malarial fever under a blanket as Mark tries to tend him while attending to household chores. And the barely-seen invalid bears little resemblance to the handsome, well-dressed young bourgeois drawn by Hablot Knight Browne in the 1843-44 serial, and elaborated by seventies illustrator Fred Barnard in The Household Edition, in such illustrations as "I was merely remarking, gentlemen— though it's a point of very little import— that the Queen of England does not happen to live in the Tower of London" (Chapter 21). The Furniss image of Mark Tapley, the second principal figure in the illustration, is both more stylized and less realistic than Barnard's in "Well, sir!" said the Captain, putting his hat a little more on one side, for it was rather tight in the crown: "You're quite a public man I calc'late" (Chapter 32). The closest parallel to the Furniss image of the suffering Martin and his dutiful nurse, but lacking the sardonic American visitor, is Fred Barnard's "Jolly!" (Chapter 33).The conversation between the candid Mark and the persistently nationalistic and dialectal Hannibal Chollop in Chapter 33, might be better characterized as Mr. Chollop Visits Mark.

"Why, what the 'tarnal!" cried the Captain. "Well! I do admire at this, I do!"

Chapter 34

Fred Barnard

In this illustration their former landlord at the National Hotel in Watertoast, Captain Kedgick, is vastly amused that Martin and Mark, now fully recovered from malarial fever, have cheated the land-speculators by remaining very much alive and leaving the swamp of Eden rather than being buried there.

Text Illustrated:

After a weary voyage of several days, they came again to that same wharf where Mark had been so nearly left behind, on the night of starting for Eden. Captain Kedgick, the landlord, was standing there, and was greatly surprised to see them coming from the boat.

‘Why, what the ‘tarnal!’ cried the Captain. ‘Well! I do admire at this, I do!’

‘We can stay at your house until to-morrow, Captain, I suppose?’ said Martin.

‘I reckon you can stay there for a twelvemonth if you like,’ retorted Kedgick coolly. ‘But our people won’t best like your coming back.’

‘Won’t like it, Captain Kedgick!’ said Martin.

‘They did expect you was a-going to settle,’ Kedgick answered, as he shook his head. ‘They’ve been took in, you can’t deny!’

‘What do you mean?’ cried Martin.

‘You didn’t ought to have received ‘em,’ said the Captain. ‘No you didn’t!’

‘My good friend,’ returned Martin, ‘did I want to receive them? Was it any act of mine? Didn’t you tell me they would rile up, and that I should be flayed like a wild cat—and threaten all kinds of vengeance, if I didn’t receive them?’

‘I don’t know about that,’ returned the Captain. ‘But when our people’s frills is out, they’re starched up pretty stiff, I tell you!’

With that, he fell into the rear to walk with Mark, while Martin and Elijah Pogram went on to the National.

‘We’ve come back alive, you see!’ said Mark.

‘It ain’t the thing I did expect,’ the Captain grumbled. ‘A man ain’t got no right to be a public man, unless he meets the public views. Our fashionable people wouldn’t have attended his le-vee, if they had know’d it.’

Nothing mollified the Captain, who persisted in taking it very ill that they had not both died in Eden. The boarders at the National felt strongly on the subject too; but it happened by good fortune that they had not much time to think about this grievance, for it was suddenly determined to pounce upon the Honourable Elijah Pogram, and give him a le-vee forthwith.

Elijah Pogram and Mrs. Hominy

Chapter 34

Sol Eytinge, Jr

Commentary:

The presence of such minor American characters as Elijah Pogram and Mrs. Hominy among Eytinge's cast of thirty implies a very different interpretation compared to Phiz's of the novel as a whole. Phiz in his forty 1843-44 illustrations graphed relationships between groups of characters, focussing on such major characters as young Martin, Seth Pecksniff, and Tom Pinch. Dickens's original illustrator, taking close direction from the novelist as surviving correspondence indicates, devoted just four engravings (10% of the entire program) to American scenes, and describes only three actual Americans: the journalists Diver and Brick, and the land agent Scadder (exclusive of the immigrants, Martin, and Mark). In other words, in the original series, American characters are important only insofar as they are related to Martin and Mark, and one sees little of the United States itself (other than the wilderness around Chuzzlewit & Co.'s cabin), because Phiz has employed such nondescript interiors as a newspaper office, a realty office, and a settlers' log cabin. To Phiz, then, Martin Chuzzlewit is an English novel that happens to incorporate a few American scenes and characters among its nineteen monthly instalments and fifty-four chapters (only six of which directly involve America). In contrast, Eytinge depicts five American scenes as the backdrops for his sixteen illustrations (i. e., 30%) and seven Americans (i. e., 23%). To Eytinge, then, this is an Anglo-American novel that lays bare the prejudices, inequalities, and dubious mores of Ante-Bellum America, particularly the morally bankrupt but economically dynamic Jacksonian period just passed (lasting from Jackson's 1828 election until the slavery issue became dominant after 1850).

Within Eytinge's depictions of representative figures of pre-Civil War American culture lie the keys to America's internecine conflict just concluded. Fred Barnard, perhaps not even having studied Eytinge's illustrations, has a view of the story more consistent wth that of his friend Hablot Knight Browne; with a much larger pictorial program to compose, sixty illustrations in total, in the 1870s Barnard devoted just eight scenes to America, and focussed on the connected issues of transportation and immigration — particularly shipping (four of the eight Household Edition woodcuts are set on deck, against a harbour, on a train, or in a settlers' cabin). In the period immediately following the American Civil War, these would have been the issues of greatest concern to English readers, along with the issue that brought America into a protracted internal conflict; Barnard, unlike the American illustrator, devotes one illustration to the slave Cicero, just as Phiz does in "Mr. Tapley succeeds in finding a jolly subject for contemplation" (chapter 17), July 1843. The equivalent illustration in Barnard's much-expanded series, "You're the pleasantest fellow I have seen yet," said Martin, clapping him on the back, "And give me a better appetite than bitters.", describes a different relationship, since the Phiz engraving concerns Mark and Cicero, whereas Barnard's woodcut depicts the protagonist himself interacting socially and upon an equality with the former slave. Neither Barnard nor Phiz expresses any interest in the two figures through whom Dickens satirizes American political, literary, and cultural pretensions, the "languid," "clockwork" Congressman Elijah Pogram and the L.L. ("Literary Lady") Mrs. Hominy, whom Mark and Martin encounter as "American originals" after fleeing Eden in chapter 34:

Among the passengers on board the steamboat, there was a faint gentleman sitting on a low camp-stool, with his legs on a high barrel of flour, as if he were looking at the prospect with his ankles, who attracted their attention speedily.

He had straight black hair, parted up the middle of his head and hanging down upon his coat; a little fringe of hair upon his chin; wore no neckcloth; a white hat; a suit of black, long in the sleeves and short in the legs; soiled brown stockings and laced shoes. His complexion, naturally muddy, was rendered muddier by too strict an economy of soap and water; and the same observation will apply to the washable part of his attire, which he might have changed with comfort to himself and gratification to his friends. He was about five and thirty; was crushed and jammed up in a heap, under the shade of a large green cotton umbrella; and ruminated over his tobacco-plug like a cow.

He was not singular, to be sure, in these respects; for every gentleman on board appeared to have had a difference with his laundress and to have left off washing himself in early youth. Every gentleman, too, was perfectly stopped up with tight plugging, and was dislocated in the greater part of his joints. But about this gentleman there was a peculiar air of sagacity and wisdom, which convinced Martin that he was no common character; and this turned out to be the case.

"How do you do sir?" said a voice in Martin's ear.

"How do you do sir?" said Martin.

It was a tall thin gentleman who spoke to him, with a carpet-cap on, and a long loose coat of green baize, ornamented about the pockets with black velvet.

"You air from Europe, sir?"

"I am," said Martin.

"You air fortunate, sir."

Martin thought so too; but he soon discovered that the gentleman and he attached different meanings to this remark.

"You air fortunate, sir, in having an opportunity of beholding our Elijah Pogram, sir."

"Your Elijahpogram!" said Martin, thinking it was all one word, and a building of some sort.

"Yes, sir."

Martin tried to look as if he understood him, but he couldn't make it out.

"Yes, sir," repeated the gentleman, "our Elijah Pogram, sir, is, at this minute, identically settin' by the en-gine biler."

The gentleman under the umbrella put his right forefinger to his eyebrow, as if he were revolving schemes of state.

"That is Elijah Pogram, is it?" said Martin.

"Yes, sir," replied the other. "That is Elijah Pogram."

Dear me!' said Martin. 'I am astonished.' But he had not the least idea who this Elijah Pogram was; having never heard the name in all his life.

"If the biler of this vessel was Toe bust, sir," said his new acquaintance, "and Toe bust now, this would be a festival day in the calendar of despotism; pretty nigh equallin', sir, in its effects upon the human race, our Fourth of glorious July. Yes, sir, that is the Honourable Elijah Pogram, Member of Congress; one of the master- minds of our country, sir. There is a brow, sir, there!"

'

"Quite remarkable," said Martin.

The remarkable Pogram, originator of the oratorical performance celebrated as "The Pogram Defiance," represents American politics, particularly the foreign-policy posturing of the Congress; Mrs. Hominy, on the other hand, represents what Americans think of as high culture:

"Sir, Mrs Hominy!"

"Lord bless that woman, Mark. She has turned up again!"

"Here she comes, sir," answered Mr Tapley. "Pogram knows her. A public character! Always got her eye upon her country, sir! If that there lady's husband is of my opinion, what a jolly old gentleman he must be!"

A lane was made; and Mrs Hominy, with the aristocratic stalk, the pocket handkerchief, the clasped hands, and the classical cap, came slowly up it, in a procession of one. Mr Pogram testified emotions of delight on seeing her, and a general hush prevailed. For it was known that when a woman like Mrs. Hominy encountered a man like Pogram, something interesting must be said.

Their first salutations were exchanged in a voice too low to reach the impatient ears of the throng; but they soon became audible, for Mrs. Hominy felt her position, and knew what was expected of her.

Mrs H. was hard upon him at first; and put him through a rigid catechism in reference to a certain vote he had given, which she had found it necessary, as the mother of the modern Gracchi, to deprecate in a line by itself, set up expressly for the purpose in German text. But Mr Pogram evading it by a well-timed allusion to the star-spangled banner, which, it appeared, had the remarkable peculiarity of flouting the breeze whenever it was hoisted where the wind blew, she forgave him. They now enlarged on certain questions of tariff, commercial treaty, boundary, importation and exportation with great effect. And Mrs Hominy not only talked, as the saying is, like a book, but actually did talk her own books, word for word.

"My! what is this!" cried Mrs Hominy, opening a little note which was handed her by her excited gentleman-usher. "Do tell! oh, well, now! on'y think!'"

And then she read aloud, as follows:

"Two literary ladies present their compliments to the mother of the modern Gracchi, and claim her kind introduction, as their talented countrywoman, to the honourable (and distinguished) Elijah Pogram, whom the two L. L.'s have often contemplated in the speaking marble of the soul-subduing Chiggle. On a verbal intimation from the mother of the M. G., that she will comply with the request of the two L. L.'s, they will have the immediate pleasure of joining the galaxy assembled to do honour to the patriotic conduct of a Pogram. It may be another bond of union between the two L. L.'s and the mother of the M. G. to observe, that the two L. L.'s are Transcendental."

Mrs. Hominy promptly rose, and proceeded to the door, whence she returned, after a minute's interval, with the two L. L.'s, whom she led, through the lane in the crowd, with all that stateliness of deportment which was so remarkably her own, up to the great Elijah Pogram. It was (as the shrill boy cried out in an ecstasy) quite the Last Scene from Coriolanus. One of the L. L.'s wore a brown wig of uncommon size. Sticking on the forehead of the other, by invisible means, was a massive cameo, in size and shape like the raspberry tart which is ordinarily sold for a penny, representing on its front the Capitol at Washington. '

"Miss Toppit, and Miss Codger!" said Mrs. Hominy.

In Eytinge's illustration, the only distinguishing feature of the pair is Pogram's Napoleonic pose. First seen in Chapter 22 at the National Hotel, where the "le-vee" for Pogram occurs in Chapter 34, Mrs. Major Hominy is described as Eytinge portrays her, tall, thin, and both physically and mentally "inflexible" :

. . . the door was thrown open in a great hurry, and an elderly gentleman entered: bringing with him a lady who certainly could not be considered young — that was matter of fact; and probably could not be considered handsome — but that was matter of opinion. She was very straight, very tall, and not at all flexible in face or figure. On her head she wore a great straw bonnet, with trimmings of the same, in which she looked as if she had been thatched by an unskillful laborer; and in her hand she held a most enormous fan.

Eytinge's illustration captures nothing of her pretentiousness, but implies that she is the literary equivalent of Congressman Pogram: a poser. From the 1867 woodcut, it would appear that there is nothing "remarkable" about either the originator of the Pogram Defiance or the Mother of the Modern Gracchi; their greatness is pure self-conceit:

Mrs. Hominy stalked in again; very erect, in proof of her aristocratic blood; and holding in her clasped hands a red cotton pocket-handkerchief, perhaps a parting gift from that choice spirit, the Major. She had laid aside her bonnet, and now appeared in a highly aristocratic and classical cap, meeting beneath her chin: a style of head-dress so admirably adapted to, her countenance, that if the late Mr. Grimaldi had appeared in the lappets of Mrs. Siddons, a more complete effect could not have been produced.

Mr. Pecksniff. Placid, calm, but proud

Chapter 35

Fred Barnard

Now back in England, Mark and Martin are astonished at the spectacle of Mr. Pecksniff sailing along an English high street with architectural plans under his arm. The publican then informs them that Pecksniff is now termed "the celebrated architect."

Commentary: Phiz and Furniss Attempt the Same Scene:

Having just returned from America, their passage paid through Mark's working as the ship's cook, Martin and Mark discover Pecksniff in a part town (possibly Portsmouth or Liverpool) about to complete the laying of two foundation stones for a new grammar-school. Thus, Pecksniff stands among other pillars of the community, awaiting his moment of recognition and popular endorsement of his status as a master builder, as as "cornerstone" of upper-middle-class society.

Although Fred Barnard in Mr. Pecksniff. Placid, calm, but proud . . . . . gently travelling across the disc, as if he were a figure in a magic lantern, has attempted to show the reaction of Mark and Martin to Pecksniff's coincidental appearance in the high street of the port city, later illustrator Harry Furniss has clearly based his illustration on one in the original serial, Hablot Knight Browne's January 1844 steel-engraving Martin is Much Gratified by an Imposing Ceremony (Chapter 35), Martin's indignation at Pecksniff's having plagiarized his design being quite the reverse of "gratification." Therefore, any analysis of the Furniss illustration must take into account the original rather than the Fred Barnard version. In the January 1844 single-page illustration, organised around the triangular apparatus for positioning the corner-stone, the local Member of Parliament, standing on a stool to increase his height and dignity (and to assist him in projecting his voice above the heads of the admiring onlookers), gestures appreciatively towards the self-satisfied architect with his left hand as he holds a silver trowel with his right, while a middle-class crowd. Barnard seems to have deliberately avoided repeating a scene that Phiz had executed so effectively, choosing instead to focus on the utter amazement of the returned travelers as they realize that Pecksniff is esteemed by the general public for his (non-existent) architectural abilities, leaving Martin feeling both chagrined and cheated out of the recognition that should be his for the grammar school's design.

Martin is Much Gratified by an Imposing Ceremony

Chapter 35

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"My grammar-school. I invented it. I did it all. He has only put four windows in, the villain, and spoilt it!"

Mark could hardly believe it at first, but being assured that it was really so, actually held him to prevent his interference foolishly, until his temporary heat was past. In the meantime, the member addressed the company on the gratifying deed which he had just performed.

He said that since he had sat in Parliament to represent the Gentlemanly Interest of that town; and he might add, the Lady Interest, he hoped, besides (pocket handkerchiefs); it had been his pleasant duty to come among them, and to raise his voice on their behalf in Another Place (pocket handkerchiefs and laughter), often. But he had never come among them, and had never raised his voice, with half such pure, such deep, such unalloyed delight, as now. "The present occasion," he said, "will ever be memorable to me; not only for the reasons I have assigned, but because it has afforded me an opportunity of becoming personally known to a gentleman —"

Here he pointed the trowel at Mr. Pecksniff, who was greeted with vociferous cheering, and laid his hand upon his heart.

"To a gentleman who, I am happy to believe, will reap both distinction and profit from this field; whose fame had previously penetrated to me — as to whose ears has it not! — but whose intellectual countenance I never had the distinguished honour to behold until this day, and whose intellectual conversation I had never before the improving pleasure to enjoy."

Everybody seemed very glad of this, and applauded more than ever.

"But I hope my Honourable Friend," said the Gentlemanly member — of course he added "if he will allow me to call him so," and of course Mr Pecksniff bowed — "will give me many opportunities of cultivating the knowledge of him; and that I may have the extraordinary gratification of reflecting in after-time that I laid on this day two first stones, both belonging to structures which shall last my life!"

Great cheering again. All this time, Martin was cursing Mr. Pecksniff up hill and down dale.

Commentary:

As Michael Steig points out, “the caption here is ironic, since Martin is outraged at Pecksniff's plagiarism of his architectural design. The tripod which supports the block and tackle will figure again in the frontispiece [one of the last plates executed], with Pecksniff dangling from it in a fitting allegory of his defeat and humiliation”.

The last chapter in the thirteenth monthly installment has young Martin, who has returned from America poorer but wiser, witnessing Pecksniff's fraudulently claiming Martin's design for a grammar school building as his own. The stout timbers assembled as a tripod, as we may surmise from the letterpress, will enable the local Member of Parliament to lever the foundation stone (centre) into place. At the right-hand base of the triangle, architectural plans in hand, stands the man of the hour, while at the left hand base of the triangle stand the other community pillars, the schoolmaster ("an ancient scholar" who reads the Latin inscription) and (we presume) his wife (left); meanwhile, standing on a bucket, the local M. P., his social eminence emphasized by the tower and flagpole immediately behind him (though according to the text, he must be on the ground since he looks up at the stone), extols the labour and character of Pecksniff. He holds a trowel in his left hand as he gestures at the celebrated architect with his right, as if Pecksniff is the metaphorical mortar that binds the community together, or another corner stone about to be set in place after winning the public design competition and thereby established as a well-known architect.

The viewer instinctively scans the admiring crowd of assembled bourgeoisie (their respectability identified by top-hats and bonnets) for Mark and young Martin, from whose perspective Dickens describes the scene. Squeezed into a corner on the ground, Mark and Martin might be the pair of observers top left, except for the fact that they are able to step forward and, unseen by the architect, survey his plans. The charity children are evident behind Pecksniff, but Phiz seems to have been unable to work in the marching band and rod-carrying Corporation, although the Mayor is present, to the right of Pecksniff, with whom he has been conversing. The purpose of the mortar and second, practicable trowel (bottom, centre) which, presumably, Pecksniff will wield in the ceremony are obvious enough, but the meaning of the overturned bottle, lying on the ground, is not — unless it is the little vase containing coins that the Member has been jingling moments earlier. The cornerstone has already been lowered into place, and Pecksniff has, as the letterpress suggests, unrolled his plans, but these have yet to receive the admiring gaze of the assembled multitude, and Martin has yet to step forward and, in private conversation with Mark, claim the plans for the grammar school as his own design, pirated (a reminder of Dickens's ill-fated lawsuit against Peter Parley's Illuminated Library for theft of A Christmas Carol.

The moment illustrated seems to be when the M. P. points his silver trowel toward Pecksniff as he remarks,

The present occasion . . . will ever be memorable to me: not only for the reasons I have assigned, but because it has afforded me an opportunity of becoming personally known to a gentleman . . . who, I am happy to believe, will reap both distinction and profit from this field . . . . [Ch. 35]

In short, Pecksniff, like Tigg, has thus far been successful at fooling the majority into believing him a pillar of society and his profession. But Martin, who feels quite the reverse of "gratified" at having witnessed the "imposing ceremony," now resolves to unmask the hypocrite and plagiarist at last.

The laying of the Foundation stone

Chapter 35

Harry Furniss

Text Illustrated:

In the meantime, the member addressed the company on the gratifying deed which he had just performed.

He said that since he had sat in Parliament to represent the Gentlemanly Interest of that town; and he might add, the Lady Interest he hoped, besides (pocket handkerchiefs); it had been his pleasant duty to come among them, and to raise his voice on their behalf in Another Place (pocket handkerchiefs and laughter), often. But he had never come among them, and had never raised his voice, with half such pure, such deep, such unalloyed delight, as now."The present occasion,"he said, "will ever be memorable to me: not only for the reasons I have assigned, but because it has afforded me an opportunity of becoming personally known to a gentleman—"

Here he pointed the trowel at Mr. Pecksniff, who was greeted with vociferous cheering, and laid his hand upon his heart.

"To a gentleman who, I am happy to believe, will reap both distinction and profit from this field: whose fame had previously penetrated to me—as to whose ears has it not!— but whose intellectual countenance I never had the distinguished honour to behold until this day, and whose intellectual conversation I had never before the improving pleasure to enjoy."

Everybody seemed very glad of this, and applauded more than ever.

"But I hope my Honourable Friend,"said the Gentlemanly member— of course he added "if he will allow me to call him so," and of course Mr. Pecksniff bowed— "will give me many opportunities of cultivating the knowledge of him; and that I may have the extraordinary gratification of reflecting in after time that I laid on this day two first stones, both belonging to structures which shall last my life!"

Great cheering again. All this time, Martin was cursing Mr. Pecksniff up hill and down dale.

Commentary:

Having just returned from America, their passage paid through Mark's working as the ship's cook, Martin and Mark discover Pecksniff in a part town (possibly Portsmouth or Liverpool) about to complete the laying of two foundation stones for a new grammar-school. Thus, Pecksniff stands among other pillars of the community, awaiting his moment of recognition and popular endorsement of his status as a master builder, as as "cornerstone" of upper-middle-class society.

Although Fred Barnard in the Household Edition illustration Mr. Pecksniff. Placid, calm, but proud . . . . . gently travelling across the disc, as if he were a figure in a magic lantern, has attempted to show the reaction of Mark and Martin to Pecksniff's coincidental appearance in the high street of the port city, Furniss has clearly based his illustration on one in the original serial, Hablot Knight Browne's January 1844 steel-engraving Martin is Much Gratified by an Imposing Ceremony (Chapter 35), Martin's indignation at Pecksniff's having plagiarized his design being quite the reverse of "gratification." Therefore, any analysis of the Furniss illustration must take into account the original rather than the Fred Barnard version. In the January 1844 single-page illustration, organised around the triangular apparatus for positioning the corner-stone, the local Member of Parliament, standing on a stool to increase his height and dignity (and to assist him in projecting his voice above the heads of the admiring onlookers), gestures appreciatively towards the self-satisfied architect with his left hand as he holds a silver trowel with his right, while a middle-class crowd (largely male), including a beadle (right) and a schoolmaster in an academic gown with his respectable wife (left); Phiz has placed Mark and Martin well to the back on the left-hand side, ready to step forward and expose the architect as a thief, the plans he has appropriated under his arm, still rolled. The second trowel (centre foreground) implies Pecksniff's central role in the ceremony.

Harry Furniss, on the other hand, almost seventy years later and long after the era's social reforms that granted the franchise to the working classes (although not, as yet, to women), foregrounds a wealthy, fashionably-dressed young wife and her daughter who will be the beneficiaries of the new Liberalism, although at this point the Beadle (centre) is gesturing to keep them behind the rope and out of the area occupied by the community's leaders: the slender, swallow-tail-coated member of parliament (left of centre), the mayor and his wife (right of centre) — and Pecksniff, assisted by several schoolboys, fatuously displaying his plans (upper left). The animated M. P. serves as the impresario for this highly staged occasion which includes a band (upper left), and Furniss develops the onlookers (less numerous than in Phiz's composition) as individuals rather than generalized members of a middle-class crowd. Maintaining the old tower and flag in the upper right, perhaps to suggest the grammar school as a time-honoured national institution, Furniss has replaced the schoolmaster and his wife, although these are appropriate to the occasion of the laying of twin cornerstones for the municipal grammar-school, with an elaborately uniformed, corpulent Mayor and his lady (holding a large bouquet) right of centre, and gives the equally substantial Beadle, a uniformed parochial authority figure, a place of prominence and something specific to do: excluding from the ceremony's stage those who are not members of the municipal elite. In analyzing Furniss's redrafted version of the Phiz illustration, one naturally wonders where Furniss has situated the normative characters with whom one enters and appraises the gathering: they are now at the right rear, immediately in front of the tower — a switched placement that coincides with the reversal of positions for the M. P. (now left centre, rather than to the right, as in Phiz's composition) and Pecksniff (formerly to the right, now at the forefront of the onlookers to the left). The overall effect of the Furniss illustration is energy and three-dimensional depth of field, with very large figures in the foreground and a diminutive Mark and Martin in the back to suggest the sheer size of the social occasion in which Martin, the designer of the building, is a rank outsider.

The Grammar School, 1840-1910, Phiz to Furniss:

Compulsory elementary education separated from Church of England control was legislated in England and Wales in the year of Dickens's death under the terms of the Endowed Schools Act (1869), so that the institution of the grammar school as a vehicle for a broadened middle-class education (emphasizing as before classical languages — but now including modern European languages, natural sciences, mathematics, history, and geography) was some forty years old by the time that Furniss executed some five hundred drawings for the sixteen volumes of Dickens's works. However, compulsory education for all children to secondary matriculation was quite another matter: England debated this question for several decades, but did not actually formally declare that all children should have access to a secondary education until 1902, just eight years prior to the publication of The Charles Dickens Library Edition. When Dickens wrote Martin Chuzzlewit, the grammar system had just been restructured under the terms of the Grammar Schools Act (1840) made it lawful to apply the income of grammar schools to purposes other than the teaching of classical languages, but change still required the consent of the schoolmaster.

Throughout the nineteenth century, the English grammar school was the middle-class equivalent of the public school, a boarding rather than a "day" school for the "classical" education of "gentlemen" and the preparation of candidates for the universities of Oxford and Cambridge. Together the grammar school and the public school maintained the distinctions of the class system in England, assuring a steady supply of civil servants and leaders in church and state respectively to support Britain's empire. Neither system paid much attention to vocational and practical training. And, in either case, secondary schooling was still reserved for an academic and social elite in the United Kingdom until the end of Victoria's reign, and literacy from 1837 to 1902 continued to be what distinguished the bourgeoisie from the proletariat, who learned for the most part "on the job." These institutions together assured social inequality, but, as the grammar school was open to middle-class girls, the grammar school laid the groundwork for female emancipation and enfranchisement. The school that Martin Chuzzlewit designed for Seth Pecksniff probably resembled that at Leeds, and drawn by Percy Robinson for Relics of Old Leeds (1896).

Chapter 33

Chapter 33Tristram wrote: "Clearly, Mr. Chollop has no actual function within the story beyond that of a vehicle for Dickens’s criticism. What aspect of American society as it was perceived by Dickens does this character stand for?"

What????? Going home already? What the heck is this about? Hardly worth the trip, although I guess Martin sees his shortcomings, which was the real reason for the sojourn.

Tristram,

The U.S. expanded so fast that great swatches of land were close to lawless. A great expanse with few good roads to travel on, towns separated by many miles of wilderness (as is so today), and many places that were just plain hard to get at. Chollop represents the iconoclast, the trapper, the frontiersman, the libertarian-anarchist the U.S. is so well known for, part myth, part reality. Meanwhile, England is pretty well civilized by this time.

EDIT: I should say England is civilized compared to many parts of the U.S.

You're right, Xan: If Mr. Chollop had cropped up in a western, I'd probably not have thought twice about him ...

Tristram wrote: "Do you think this change and development in Martin likely and believable? ..."

Tristram wrote: "Do you think this change and development in Martin likely and believable? ..."I really did. Nothing like being destitute and near death to change one's outlook on life, and to fully appreciate someone else's care and friendship. Certainly the change in Martin was not nearly as quick and hard to believe as that of Tom Pinch and his glowing opinion of Pecksniff. I thought Dickens did very well with this transformation.

As soon as Mark and Martin reached England, I wondered if they would run into either Pinch or Westlock. It had to be someone we knew, didn't it? Pecksniff did nicely. I hope he'll get his comeuppance, and that Martin will be paid for his work, giving him the wherewithal to wed Mary.

Jantine - I'm with you. That room at the inn sounds like a cozy place to hide away with a good book on a rainy day. (Wish I could be there now.... lots of interruptions here today...)

I hope Martin holds on to the land for a century or so - there are probably a bunch of condos there now, and his heirs would have eventually made some good money from his investment.

Kim - I'm not surprised that your youth group had a Valentine's Day party - he was a saint, after all :-) - but one must assume there were no chaperones around during that spin-the-bottle game. The thought of kissing someone who chews tobacco is not appealing.

Mary Lou wrote: "I really did. Nothing like being destitute and near death to change one's outlook on life, and to fully appreciate someone else's care and friendship. Certainly the change in Martin was not nearly as quick and hard to believe as that of Tom Pinch and his glowing opinion of Pecksniff. I thought Dickens did very well with this transformation."

You are right, Mary Lou: There are moments when everything is on the edge and these moments can lead you to reconsidering your life and redefining your values and aims. I'm speaking from experience there, but I must also say that by and by old patterns of thinking may creep back in. Let's see how Martin will succeed in keeping alive his newly-won insights and the will to act upon them.

I found Tom Pinch's sudden change of mind on Pecksniff quite conclusive: He had thought all the world in Pecksniff and then found that he not only did not live up to his expectations but was actually a base scoundrel towards the damsel Pinch adores. It's quite understandable that his idol is shattered now. What I do not really understand, though, is that it took Pinch so long to see through such a pathetic hypocrite as Pecky.

Another interesting question, which is also taken up in the book, is whether this incident will blight his general confidence in human nature.

You are right, Mary Lou: There are moments when everything is on the edge and these moments can lead you to reconsidering your life and redefining your values and aims. I'm speaking from experience there, but I must also say that by and by old patterns of thinking may creep back in. Let's see how Martin will succeed in keeping alive his newly-won insights and the will to act upon them.

I found Tom Pinch's sudden change of mind on Pecksniff quite conclusive: He had thought all the world in Pecksniff and then found that he not only did not live up to his expectations but was actually a base scoundrel towards the damsel Pinch adores. It's quite understandable that his idol is shattered now. What I do not really understand, though, is that it took Pinch so long to see through such a pathetic hypocrite as Pecky.