The History Book Club discussion

This topic is about

The Towers of Silence

HISTORY OF SOUTHERN ASIA

>

INTRODUCTION - BOOK THREE - THE TOWERS OF SILENCE - (Spoiler Thread)

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

This is a review that the late Christopher Hitchens did for the series

Victoria's Secret

A review by Christopher Hitchens

[Ed. note: This review covers three books, Raj Quartet: The Jewel in the Crown/ The Day of the Scorpion and Raj Quartet: The Towers of Silence/ A Division of the Spoils.]

There are not as many theories about the fall of the British Empire as there once were about the eclipse of its Roman predecessor, but one of the micro theories has always appealed to me more than any of the macro explanations. And it concerns India. For the first century or so of British dominion over the subcontinent, the men of the East India Company more or less took their chances. They made and lost reputations, and established or overthrew regional domains, and their massive speculations led to gain or ruin or (as in the instance of Warren Hastings) both. Meanwhile, they were encouraged to pick up the custom of the country, acquire a bit of the lingo, and develop a taste for "native" food, but -- this in a bit of a whisper -- be very careful about the local women. Things in that sensitive quarter could be arranged, but only with the most exquisite discretion.

Thus the British developed a sort of modus vivendi that lasted until the trauma of 1857: the first Indian armed insurrection (still known as "the Mutiny" because it occurred among those the British had themselves trained and organized). Then came the stern rectitude of direct rule from London, replacing the improvised jollities and deal-making of "John Company," as the old racket had come to be affectionately known. And in the wake of this came the dreaded memsahib: the wife and companion and helpmeet of the officer, the district commissioner, the civil servant, and the judge. She was unlikely to tolerate the pretty housemaid or the indulgent cook. Worse, she was herself in need of protection against even a misdirected or insolent native glance. To protect white womanhood, the British erected a wall between themselves and those they ruled. They marked off cantonments, rigidly inscribing them on the map. They built country clubs and Anglican churches where ladies could go, under strict escort, and be unmolested. They invented a telling term -- chi-chi -- to define, and to explain away, the number of children and indeed adults who looked as if they might have had English fathers and Indian mothers or (even more troubling) the reverse. Gradually, the British withdrew into a private and costive and repressed universe where eventually they could say, as the angry policeman Ronald Merrick does in The Day of the Scorpion, the second volume of Paul Scott's Raj Quartet: "We don't rule this country any more. We preside over it."

In this anecdotal theory, the decline of the British Raj can be attributed to the subtle influence of the female, to the male need to protect her (and thus fence her in), and to the related male need to fight for her honor and to punish with exceptional severity anybody who seems to impugn it.

"After all," says the district collector Turton in E. M. Forster's A Passage to India, "it's our women who make everything more difficult out here." And Paul Scott accepted that he had little choice but to follow the track that Forster had laid down.

I choose the word track with care, since the railway network was (apart from Lord Macaulay's education system) the most enduring achievement of the British Raj: the most proudly flourished emblem of the unity and punctuality it brought to the nation, as well as the speediest possible method of annexing Indian capital and shipping it to the ports of Bombay, Madras, and Calcutta in order to fuel the English Industrial Revolution. The Indian railways feature by name in Bhowani Junction, one of the most gripping of John Masters's Anglo-Indian novels, and their imagery appears to have oppressed Paul Scott.

According to Scott's brilliant biographer Hilary Spurling, whose introduction to this handsome two-volume Everyman edition is a jewel in itself, Scott felt that "Forster loomed over literary India like a train terminus beyond which no other novelist could be permitted to travel by the critics."

When Scott deliberately chose a rape as his central event -- as it had been in Forster's Passage -- we can see that he ultimately resolved to face the comparison and attempt to transcend it. To borrow the language of "cultural studies," he did so by exploring the interactions of race, class, and gender, as Orwell had tried to do in Burmese Days, while not forgetting the politics.

In the last of Scott's tetralogy (A Division of the Spoils), we meet a certain Captain Purvis, who represents the new, brusque British postwar consensus about India, namely that it was and is

"a wasted asset, a place irrevocably ruined by the interaction of a conservative and tradition-bound population and an indolent bone-headed and utterly uneducated administration, an elitist bureaucracy so out of touch with the social and economic thinking of even just the past hundred years that you honestly wonder where they've come from...The most sensible thing for us to do is get rid of it fast to the first bidder before it becomes an intolerable burden."

This no doubt partly represents Scott's own view, or the view he took as a liberal-minded young officer watching the scenery being dismantled after the defeat of Japan and before the division of the spoils into India and Pakistan. It was obviously high time for the British to leave.

Yet there is one last train to be caught, the one stopped in the desert in 1947 by a Hindu mob, who drag a Muslim from the carriage and do him to death beside the tracks. The train resumes its journey, bearing its complement of British officials away from the distressing scene. Sergeant Guy Perron, who has listened to Purvis's rational rant and who has quarrels of his own with the authorities (and whom I think we are to see as the Scott figure in the story), is hit hard as he watches the former rulers make good their escape, and finds something unpleasantly "greasy and evasive" in the snaking movement of the train that carries them away. The ensuing awful bloodbath of partition took place principally at the railway stations and on the trains, but by then the British could claim that they had washed their hands rather than stained them.

Scott's work on India, which is really a quintet given the coda Staying On, is tense and beautiful in a way that Forster's is not, because it understands that Fabian utilitarianism has its limits, too. The novels also possess a dimension of historical irony, because they understand that the British stayed too long and left too soon. The date on which it became evident that the game was up is a date that every Indian still knows: April 13, 1919.

Maddened by a report of a mob attack on (yes, it had to be) an Englishwoman, Brigadier General Reginald Dyer ordered his soldiers to fire into a crowd in the public square in the northern city of Amritsar. That event was the Boston Massacre or the Lexington and Concord of the Indian revolution. From then on, it was a matter not of whether the British would quit, but of when. Scott understands this so well that he makes the name of that Amritsar square -- Jallianwallah -- a totem that recurs throughout the books.

But there remains a question of, if you like, etiquette. How exactly do you behave when you want to leave and know you have to leave but don't want to do so in an unseemly rush? Moreover, how do you conduct yourself when Japanese imperialism makes a sudden bid for mastery in Asia, which means that British rule will be succeeded not by English-trained Indian democrats and liberals, but by Hirohito's Co-Prosperity Sphere? These are difficulties that Forster never had to confront. (The Amritsar events took place years after the visit to India that inspired his landmark novel.) Scott's account begins at the precise moment, in 1942, when the British have made the grotesque mistake of declaring war on India's behalf, without consultation, and when Mahatma Gandhi has announced that they must "quit India" and leave her "to god or to anarchy" (in the circumstances of growing Hindu-Muslim fratricide, something of a false antithesis). Depressed by Gandhi's failure to take the Japanese threat seriously, the old missionary lady Edwina Crane removes his picture from her wall, revealing:

The upright oblong patch of paler distemper, all that was left to Miss Crane of the Mahatma's spectacled, smiling image, the image of a man she had put her faith in which she had now transferred to Mr Nehru and Mr Rajagopalachari who obviously understood the different degrees of tyranny men could exercise and, if there had to be a preference, probably preferred to live a while longer with the imperial degree in order not only to avoid submitting to but to resist the totalitarian.

And of course it is Miss Crane, trying to help, who is viciously manhandled by the rioters. And of course it is Daphne Manners, the gawky girl who defies convention so much as to have an affair with an Indian boy, who is gang-raped during the same disorders. Adela Quested in A Passage to India is making up her hysterical allegation about what happened in the Marabar caves, but Daphne is so eager to shield her genuine Indian lover that she refuses to testify about the real rapists who came upon them when they were lying together. And the boyfriend, who is charged with the rape and sent to prison, is himself sexually assaulted by Ronald Merrick during the course of his interrogation. Forster never dared attempt this level of complexity, or indeed of realism.

The ramifications of a small but cruel injustice allow Scott to test the whole fabric of decaying British India. Gradually, we come to understand that the British have betrayed their own promise -- of impartial, unifying, and modernizing administration -- and are resorting to divide-and-rule tactics. These are best described by Daphne's boyfriend, Hari Kumar, who notices

"the extent to which the English now seem to depend upon the divisions in Indian political opinion perpetuating their own rule at least until after the war...They prefer Muslims to Hindus (because of the closer affinity that exists between God and Allah than exists between God and the Brahma), are constitutionally predisposed to Indian princes, emotionally affected by the thought of untouchables, and mad keen about the peasants who look on any Raj as God."

Poor Daphne, less political and more intuitive, sees where things have gone wrong in a different way:

"Perhaps at one time there was a moral as well as a physical force at work. But the moral thing had gone sour. Has gone sour. Our faces reflect the sourness. The women look worse than the men because consciousness of physical superiority is unnatural to us. A white man in India can feel physically superior without unsexing himself. But what happens to a woman if she tells herself that ninety-nine per cent of the men she sees are not men at all, but creatures of an inferior species whose color is their main distinguishing mark?"

Daphne's great-aunt, Lady Ethel Manners, the widow of a former governor, is outraged by Lord Mountbatten's hasty agreement to partition:

"The creation of Pakistan is our crowning failure. I can't bear it...Our only justification for two hundred years of power was unification. But we've divided one composite nation into two."

The Raj Quartet, as these excerpts help to make plain, is not so much about India as it is about the British. To understand how they betrayed their own mission in the subcontinent is to understand, in Scott's words, how "in Ranpur, and in places like Ranpur, the British came to the end of themselves as they were."

Victoria's Secret

A review by Christopher Hitchens

[Ed. note: This review covers three books, Raj Quartet: The Jewel in the Crown/ The Day of the Scorpion and Raj Quartet: The Towers of Silence/ A Division of the Spoils.]

There are not as many theories about the fall of the British Empire as there once were about the eclipse of its Roman predecessor, but one of the micro theories has always appealed to me more than any of the macro explanations. And it concerns India. For the first century or so of British dominion over the subcontinent, the men of the East India Company more or less took their chances. They made and lost reputations, and established or overthrew regional domains, and their massive speculations led to gain or ruin or (as in the instance of Warren Hastings) both. Meanwhile, they were encouraged to pick up the custom of the country, acquire a bit of the lingo, and develop a taste for "native" food, but -- this in a bit of a whisper -- be very careful about the local women. Things in that sensitive quarter could be arranged, but only with the most exquisite discretion.

Thus the British developed a sort of modus vivendi that lasted until the trauma of 1857: the first Indian armed insurrection (still known as "the Mutiny" because it occurred among those the British had themselves trained and organized). Then came the stern rectitude of direct rule from London, replacing the improvised jollities and deal-making of "John Company," as the old racket had come to be affectionately known. And in the wake of this came the dreaded memsahib: the wife and companion and helpmeet of the officer, the district commissioner, the civil servant, and the judge. She was unlikely to tolerate the pretty housemaid or the indulgent cook. Worse, she was herself in need of protection against even a misdirected or insolent native glance. To protect white womanhood, the British erected a wall between themselves and those they ruled. They marked off cantonments, rigidly inscribing them on the map. They built country clubs and Anglican churches where ladies could go, under strict escort, and be unmolested. They invented a telling term -- chi-chi -- to define, and to explain away, the number of children and indeed adults who looked as if they might have had English fathers and Indian mothers or (even more troubling) the reverse. Gradually, the British withdrew into a private and costive and repressed universe where eventually they could say, as the angry policeman Ronald Merrick does in The Day of the Scorpion, the second volume of Paul Scott's Raj Quartet: "We don't rule this country any more. We preside over it."

In this anecdotal theory, the decline of the British Raj can be attributed to the subtle influence of the female, to the male need to protect her (and thus fence her in), and to the related male need to fight for her honor and to punish with exceptional severity anybody who seems to impugn it.

"After all," says the district collector Turton in E. M. Forster's A Passage to India, "it's our women who make everything more difficult out here." And Paul Scott accepted that he had little choice but to follow the track that Forster had laid down.

I choose the word track with care, since the railway network was (apart from Lord Macaulay's education system) the most enduring achievement of the British Raj: the most proudly flourished emblem of the unity and punctuality it brought to the nation, as well as the speediest possible method of annexing Indian capital and shipping it to the ports of Bombay, Madras, and Calcutta in order to fuel the English Industrial Revolution. The Indian railways feature by name in Bhowani Junction, one of the most gripping of John Masters's Anglo-Indian novels, and their imagery appears to have oppressed Paul Scott.

According to Scott's brilliant biographer Hilary Spurling, whose introduction to this handsome two-volume Everyman edition is a jewel in itself, Scott felt that "Forster loomed over literary India like a train terminus beyond which no other novelist could be permitted to travel by the critics."

When Scott deliberately chose a rape as his central event -- as it had been in Forster's Passage -- we can see that he ultimately resolved to face the comparison and attempt to transcend it. To borrow the language of "cultural studies," he did so by exploring the interactions of race, class, and gender, as Orwell had tried to do in Burmese Days, while not forgetting the politics.

In the last of Scott's tetralogy (A Division of the Spoils), we meet a certain Captain Purvis, who represents the new, brusque British postwar consensus about India, namely that it was and is

"a wasted asset, a place irrevocably ruined by the interaction of a conservative and tradition-bound population and an indolent bone-headed and utterly uneducated administration, an elitist bureaucracy so out of touch with the social and economic thinking of even just the past hundred years that you honestly wonder where they've come from...The most sensible thing for us to do is get rid of it fast to the first bidder before it becomes an intolerable burden."

This no doubt partly represents Scott's own view, or the view he took as a liberal-minded young officer watching the scenery being dismantled after the defeat of Japan and before the division of the spoils into India and Pakistan. It was obviously high time for the British to leave.

Yet there is one last train to be caught, the one stopped in the desert in 1947 by a Hindu mob, who drag a Muslim from the carriage and do him to death beside the tracks. The train resumes its journey, bearing its complement of British officials away from the distressing scene. Sergeant Guy Perron, who has listened to Purvis's rational rant and who has quarrels of his own with the authorities (and whom I think we are to see as the Scott figure in the story), is hit hard as he watches the former rulers make good their escape, and finds something unpleasantly "greasy and evasive" in the snaking movement of the train that carries them away. The ensuing awful bloodbath of partition took place principally at the railway stations and on the trains, but by then the British could claim that they had washed their hands rather than stained them.

Scott's work on India, which is really a quintet given the coda Staying On, is tense and beautiful in a way that Forster's is not, because it understands that Fabian utilitarianism has its limits, too. The novels also possess a dimension of historical irony, because they understand that the British stayed too long and left too soon. The date on which it became evident that the game was up is a date that every Indian still knows: April 13, 1919.

Maddened by a report of a mob attack on (yes, it had to be) an Englishwoman, Brigadier General Reginald Dyer ordered his soldiers to fire into a crowd in the public square in the northern city of Amritsar. That event was the Boston Massacre or the Lexington and Concord of the Indian revolution. From then on, it was a matter not of whether the British would quit, but of when. Scott understands this so well that he makes the name of that Amritsar square -- Jallianwallah -- a totem that recurs throughout the books.

But there remains a question of, if you like, etiquette. How exactly do you behave when you want to leave and know you have to leave but don't want to do so in an unseemly rush? Moreover, how do you conduct yourself when Japanese imperialism makes a sudden bid for mastery in Asia, which means that British rule will be succeeded not by English-trained Indian democrats and liberals, but by Hirohito's Co-Prosperity Sphere? These are difficulties that Forster never had to confront. (The Amritsar events took place years after the visit to India that inspired his landmark novel.) Scott's account begins at the precise moment, in 1942, when the British have made the grotesque mistake of declaring war on India's behalf, without consultation, and when Mahatma Gandhi has announced that they must "quit India" and leave her "to god or to anarchy" (in the circumstances of growing Hindu-Muslim fratricide, something of a false antithesis). Depressed by Gandhi's failure to take the Japanese threat seriously, the old missionary lady Edwina Crane removes his picture from her wall, revealing:

The upright oblong patch of paler distemper, all that was left to Miss Crane of the Mahatma's spectacled, smiling image, the image of a man she had put her faith in which she had now transferred to Mr Nehru and Mr Rajagopalachari who obviously understood the different degrees of tyranny men could exercise and, if there had to be a preference, probably preferred to live a while longer with the imperial degree in order not only to avoid submitting to but to resist the totalitarian.

And of course it is Miss Crane, trying to help, who is viciously manhandled by the rioters. And of course it is Daphne Manners, the gawky girl who defies convention so much as to have an affair with an Indian boy, who is gang-raped during the same disorders. Adela Quested in A Passage to India is making up her hysterical allegation about what happened in the Marabar caves, but Daphne is so eager to shield her genuine Indian lover that she refuses to testify about the real rapists who came upon them when they were lying together. And the boyfriend, who is charged with the rape and sent to prison, is himself sexually assaulted by Ronald Merrick during the course of his interrogation. Forster never dared attempt this level of complexity, or indeed of realism.

The ramifications of a small but cruel injustice allow Scott to test the whole fabric of decaying British India. Gradually, we come to understand that the British have betrayed their own promise -- of impartial, unifying, and modernizing administration -- and are resorting to divide-and-rule tactics. These are best described by Daphne's boyfriend, Hari Kumar, who notices

"the extent to which the English now seem to depend upon the divisions in Indian political opinion perpetuating their own rule at least until after the war...They prefer Muslims to Hindus (because of the closer affinity that exists between God and Allah than exists between God and the Brahma), are constitutionally predisposed to Indian princes, emotionally affected by the thought of untouchables, and mad keen about the peasants who look on any Raj as God."

Poor Daphne, less political and more intuitive, sees where things have gone wrong in a different way:

"Perhaps at one time there was a moral as well as a physical force at work. But the moral thing had gone sour. Has gone sour. Our faces reflect the sourness. The women look worse than the men because consciousness of physical superiority is unnatural to us. A white man in India can feel physically superior without unsexing himself. But what happens to a woman if she tells herself that ninety-nine per cent of the men she sees are not men at all, but creatures of an inferior species whose color is their main distinguishing mark?"

Daphne's great-aunt, Lady Ethel Manners, the widow of a former governor, is outraged by Lord Mountbatten's hasty agreement to partition:

"The creation of Pakistan is our crowning failure. I can't bear it...Our only justification for two hundred years of power was unification. But we've divided one composite nation into two."

The Raj Quartet, as these excerpts help to make plain, is not so much about India as it is about the British. To understand how they betrayed their own mission in the subcontinent is to understand, in Scott's words, how "in Ranpur, and in places like Ranpur, the British came to the end of themselves as they were."

message 4:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Nov 23, 2014 06:07PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Towers of Silence: Zoroastrian Architectures for the Ritual of Death

http://socks-studio.com/2012/02/09/to...

http://www.slate.com/blogs/atlas_obsc...

http://socks-studio.com/2012/02/09/to...

http://www.slate.com/blogs/atlas_obsc...

Indian History Sourcebook:

Sir Monier Monier-Williams:

The Towers of Silence, 1870

http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/india/...

Sir Monier Monier-Williams:

The Towers of Silence, 1870

http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/india/...

message 8:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Nov 23, 2014 06:15PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Reviews:

Jean G. Zorn | New York Times Book Review

“Paul Scott’s vision is both precise and painterly. Like an engraver crosshatching I the illusion of fullness, he selects nuances that will make his characters take on depth and poignancy.”

Guardian

“One has to admire Mr. Scott’s gifts as a buttonholing storyteller, and his rich, close-textured prose; his descriptions of action and of certain kinds of relationships are superb.”

Peter Green | New Republic

“What has always astonished me about The Raj Quartet is its sense of sophisticated and total control of its gigantic scenario and highly varied characters. The four volumes constitute perfectly interlocking movement of a grand overall design. The politics are handled with an expertise that intrigues and never bores, and are always seen in terms of individuals.”

Jean G. Zorn | New York Times Book Review

“Paul Scott’s vision is both precise and painterly. Like an engraver crosshatching I the illusion of fullness, he selects nuances that will make his characters take on depth and poignancy.”

Guardian

“One has to admire Mr. Scott’s gifts as a buttonholing storyteller, and his rich, close-textured prose; his descriptions of action and of certain kinds of relationships are superb.”

Peter Green | New Republic

“What has always astonished me about The Raj Quartet is its sense of sophisticated and total control of its gigantic scenario and highly varied characters. The four volumes constitute perfectly interlocking movement of a grand overall design. The politics are handled with an expertise that intrigues and never bores, and are always seen in terms of individuals.”

message 9:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Nov 23, 2014 06:19PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

TOWERS OF SILENCE CASE - 1874

This case, which was tried at the Criminal Sessions of the Bombay High Court in 1874, and the circumstances which led to it, created a great sensation in Bombay, and intense agitation among the Parsis. The number of persons committed to the Sessions for trial was 50, 48 Parsis and 2 Hindus. The case came on before Mr. Justice Green and a special jury, consisting mainly of Englishmen with one Parsi. Ferguson and Inverarity appeared for the Crown. Anstey, Pherozeshah Mehta, Starling, Mayhew, Jackson, Branson, and Leith appeared for the different accused.

The prosecution case was that the accused had assembled on 4th April 1873, to commit mischief and destroy property with the common object of enforcing a supposed legal right by use of' criminal force. They were charged with being members of an unlawful assembly and of rioting.

in opening the case, counsel for prosecution pointed out that it was immaterial to whom the land legally belonged. The object of the law was to prevent a breach of peace. It becomes a criminal trespass if one enters upon a land for asserting a supposed right to it, if his object is to interfere with, insult or annoy somebody else in possession of the land.

The facts of the case briefly were that Cooverji Pragji and Jacob Jamal had purchased a plot of land adjoining the compound wall of the Parsi Towers of Silence on Malabar Hill. Accused No.1 claimed the same land as a lessee from the trustees of the Parsi Panchayat, in whom the Towers and the land appertaining to it were vested. Cooverji and Jacob desired to build houses and lay out a road on the land they had purchased. In March 1873, Cooverji and Jacob with one Duffy, whom they had engaged as their builder, went on the site to mark out boundaries and prepare for the erection of certain structures. They knew that accused No.1 was claiming the land as belonging to him. Apprehending trouble, they had applied to the Commissioner of Police for assistance; and a European constable and three or four sepoys were posted in the vicinity of the land. It seems that after marking the boundaries, building materials were brought to the land; and a chawl was hastily built up and a tent was also erected for Duffy in which certain furniture was put. Thereafter Cooverji applied for permission to carry out blasting operations on the land. It was alleged that when the police, went on the site for beating a Bataki, to inquire whether any person had any objection to the blasting operations, they saw accused No. I and asked him if he had any objection. He replied, "if I have an objection, I will send it to the proper office; but these people have been damaging my trees and I will damage their chawl". It seems that the police authorities were conscious that this land was a trouble spot; and they posted police sepoys on the roads leading to the Towers of Silence. It was also alleged that 61 persons, armed with sticks and bludgeons, had collected near Deputy Superintendent of Police Brown's residence, apparently with a view to overawe the Parsi trouble-makers. Brown on visiting the site saw a very large crowd of about 200 persons including Parsis, Mahommedans and Hindus, collected near the Towers of Silence, some of them armed with sticks and bamboos. Sensing trouble, Brown left a number of policemen under Inspector McDermott, and went to inform the Police Commissioner. According to the prosecution, the mob made a rush on the chawl and the tent, which they demolished in a short time, causing damage to some property in the tent. When the police tried to check the rioters, they shouted, according to the prosecution, in a defiant mood, "We shall destroy this structure. Let the Sarkar fine us. The Parsi Panchayat has enough money to pay." The Commissioner of Police, Mr. Souter, soon arrived with reinforcements; and 30 persons were put under arrest. It was alleged that in the fracas some persons were assaulted and hurt.

The police then tried to enter the compound of the Towers in order to apprehend some of the rioters who had escaped there. The police, in spite of the protests of the Parsis, entered the compound and a number of persons were arrested within the precincts of the Towers. In the course of the trial, Brown admitted in his cross-examination, that several of the 61 persons who had gathered near his residence, armed with sticks and bludgeons, were the men hired by Cooverji and Jacob. He further admitted that he was not aware of a government proclamation of 1792 against the forcible entry of persons, including the police, into sacred places and consecrated grounds. He further said that he did not know that the Parsis pray in the Suggree (fire-place) in the compound of the Towers after funerals. Under Anstey's merciless cross-examination, this police officer was driven to admit that the sticks alleged to have been used by the rioters were not produced at the police station on the day of the incident; and further that bamboos were growing all over Malabar Hill. One prosecution witness, alleged to have been assaulted and struck by one of the accused, said in cross-examination that he did no know who hit him. He said that he had pointed out to one of the accused in the police court, owing to the "Zoolurn" (compulsion) of a police havaldar whom he pointed out. Souter, the Police Commissioner, himself admitted that some of the accused whom he had handcuffed were respectable men; but he had handcuffed them because he thought that they might try to escape from police custody. He further said that he had released the 61 persons armed with sticks who had gathered near Brown's residence, as he had reasons to believe that they had not committed any offence. He further admitted that before the Bataki was beaten, the Secretary of the Parsi Panchayat had frequently seen him, in connection with allegations of trespass on the sacred land, by persons employed by Cooverji and Jacob. He had further to admit that the Secretary had reminded him of the correspondence exchanged in the past eight years, about this property. He also admitted that police assistance had frequently been sought by the Parsi Panchayat in connection with this ground. From the disclosures made in the evidence, it seemed that the police had behaved in a very highhanded, partisan and provocative manner.

In the course of the trial, Anstey, as usual, constantly came into collision with the judge. The proceedings were interrupted with frequent "breezes". At one stage, while Anstey was trying to establish a contradiction in a witness's evidence, the judge interrupted by saying that the evidence of the witness was substantially the same as he had given in the police court. When Anstey objected to the interruption, the judge observed, "I shall interrupt in any way I think fit." Anstey retorted, "in that case, My Lord, the matter shall go further than this; that is all. Justice shall be done to the prisoners; and conviction shall not be obtained if I can help it. I repeat my objection to these interruptions. "Anstey, of course, had his nerves frayed as usual, and was in a most bellicose mood. When the prosecution counsel raised an objection to a question put by Anstey, Anstey observed, "no doubt, every objection will be made that mediocrity can invent and complaisance will allow." At a later stage, the judge addressing Anstey said, "if you insist on interrupting the proceedings, I shall have to fine you." Anstey: " If you fine me, I shall take the opinion of another court."

In his address to the jury, Anstey's plea was that if a trespasser builds upon the land of another person, that other has the right to pull down the structure. Referring to the withdrawal of the prosecution against various persons in the High Court and in the police court, Anstey observed that altogether 32 accused had been discharged in the two courts, due to "egregious and monstrous blunders" in identification. The main point which he urged upon the jury was, that the police had acted in a most tactless, provoking and high-handed manner, and were themselves to blame for any disturbance that had taken place. He made severe strictures on the conduct of the police officers, condemning the partisan behaviour of Brown, describing McDermott's conduct as "shamelessness which he could have only acquired since joining the police force". He dubbed Brown as unscrupulous; and the Commissioner himself as "a vain, weak, and imperious man." There were allegations that Souter himself had behaved in a very tactless and provocative manner, entering the precincts of the Towers On horseback, which led to considerable excitement among the Parsi crowd gathered there. Anstey wound up with the peroration, "your verdict will either be quoted for evermore hereafter in Bombay, as a precedent for every kind of tyranny, usurpation and injustice on the part of the police, or it will be applauded and appealed to as a great constitutional precedent."

The jury after taking time to consider their verdict brought in a unanimous verdict of not guilty against all the accused.

In those days, it seems, the Bombay High Court followed the British practice of locking up the jury in a room, until they reached unanimity in their verdict. There was a story that the Parsi juror, who was a big-built, burly man, refused to budge from his place, unless all the accused were acquitted; and ultimately tired out his co-jurors into agreeing to a unanimous verdict of not guilty as regards all the accused.

Anstey's long, successful, stormy, and colourful career at the Bombay Bar ended with this memorable case. It was long remembered in Bombay as one of the most striking and spectacular of his forensic triumphs, due mainly to his fearless and tenacious advocacy of the cause of his clients. He died shortly after, leaving a name which was commemorated in a grateful song, sung by Parsis at weddings and other auspicious occasions, for years after his death.

This case, which was tried at the Criminal Sessions of the Bombay High Court in 1874, and the circumstances which led to it, created a great sensation in Bombay, and intense agitation among the Parsis. The number of persons committed to the Sessions for trial was 50, 48 Parsis and 2 Hindus. The case came on before Mr. Justice Green and a special jury, consisting mainly of Englishmen with one Parsi. Ferguson and Inverarity appeared for the Crown. Anstey, Pherozeshah Mehta, Starling, Mayhew, Jackson, Branson, and Leith appeared for the different accused.

The prosecution case was that the accused had assembled on 4th April 1873, to commit mischief and destroy property with the common object of enforcing a supposed legal right by use of' criminal force. They were charged with being members of an unlawful assembly and of rioting.

in opening the case, counsel for prosecution pointed out that it was immaterial to whom the land legally belonged. The object of the law was to prevent a breach of peace. It becomes a criminal trespass if one enters upon a land for asserting a supposed right to it, if his object is to interfere with, insult or annoy somebody else in possession of the land.

The facts of the case briefly were that Cooverji Pragji and Jacob Jamal had purchased a plot of land adjoining the compound wall of the Parsi Towers of Silence on Malabar Hill. Accused No.1 claimed the same land as a lessee from the trustees of the Parsi Panchayat, in whom the Towers and the land appertaining to it were vested. Cooverji and Jacob desired to build houses and lay out a road on the land they had purchased. In March 1873, Cooverji and Jacob with one Duffy, whom they had engaged as their builder, went on the site to mark out boundaries and prepare for the erection of certain structures. They knew that accused No.1 was claiming the land as belonging to him. Apprehending trouble, they had applied to the Commissioner of Police for assistance; and a European constable and three or four sepoys were posted in the vicinity of the land. It seems that after marking the boundaries, building materials were brought to the land; and a chawl was hastily built up and a tent was also erected for Duffy in which certain furniture was put. Thereafter Cooverji applied for permission to carry out blasting operations on the land. It was alleged that when the police, went on the site for beating a Bataki, to inquire whether any person had any objection to the blasting operations, they saw accused No. I and asked him if he had any objection. He replied, "if I have an objection, I will send it to the proper office; but these people have been damaging my trees and I will damage their chawl". It seems that the police authorities were conscious that this land was a trouble spot; and they posted police sepoys on the roads leading to the Towers of Silence. It was also alleged that 61 persons, armed with sticks and bludgeons, had collected near Deputy Superintendent of Police Brown's residence, apparently with a view to overawe the Parsi trouble-makers. Brown on visiting the site saw a very large crowd of about 200 persons including Parsis, Mahommedans and Hindus, collected near the Towers of Silence, some of them armed with sticks and bamboos. Sensing trouble, Brown left a number of policemen under Inspector McDermott, and went to inform the Police Commissioner. According to the prosecution, the mob made a rush on the chawl and the tent, which they demolished in a short time, causing damage to some property in the tent. When the police tried to check the rioters, they shouted, according to the prosecution, in a defiant mood, "We shall destroy this structure. Let the Sarkar fine us. The Parsi Panchayat has enough money to pay." The Commissioner of Police, Mr. Souter, soon arrived with reinforcements; and 30 persons were put under arrest. It was alleged that in the fracas some persons were assaulted and hurt.

The police then tried to enter the compound of the Towers in order to apprehend some of the rioters who had escaped there. The police, in spite of the protests of the Parsis, entered the compound and a number of persons were arrested within the precincts of the Towers. In the course of the trial, Brown admitted in his cross-examination, that several of the 61 persons who had gathered near his residence, armed with sticks and bludgeons, were the men hired by Cooverji and Jacob. He further admitted that he was not aware of a government proclamation of 1792 against the forcible entry of persons, including the police, into sacred places and consecrated grounds. He further said that he did not know that the Parsis pray in the Suggree (fire-place) in the compound of the Towers after funerals. Under Anstey's merciless cross-examination, this police officer was driven to admit that the sticks alleged to have been used by the rioters were not produced at the police station on the day of the incident; and further that bamboos were growing all over Malabar Hill. One prosecution witness, alleged to have been assaulted and struck by one of the accused, said in cross-examination that he did no know who hit him. He said that he had pointed out to one of the accused in the police court, owing to the "Zoolurn" (compulsion) of a police havaldar whom he pointed out. Souter, the Police Commissioner, himself admitted that some of the accused whom he had handcuffed were respectable men; but he had handcuffed them because he thought that they might try to escape from police custody. He further said that he had released the 61 persons armed with sticks who had gathered near Brown's residence, as he had reasons to believe that they had not committed any offence. He further admitted that before the Bataki was beaten, the Secretary of the Parsi Panchayat had frequently seen him, in connection with allegations of trespass on the sacred land, by persons employed by Cooverji and Jacob. He had further to admit that the Secretary had reminded him of the correspondence exchanged in the past eight years, about this property. He also admitted that police assistance had frequently been sought by the Parsi Panchayat in connection with this ground. From the disclosures made in the evidence, it seemed that the police had behaved in a very highhanded, partisan and provocative manner.

In the course of the trial, Anstey, as usual, constantly came into collision with the judge. The proceedings were interrupted with frequent "breezes". At one stage, while Anstey was trying to establish a contradiction in a witness's evidence, the judge interrupted by saying that the evidence of the witness was substantially the same as he had given in the police court. When Anstey objected to the interruption, the judge observed, "I shall interrupt in any way I think fit." Anstey retorted, "in that case, My Lord, the matter shall go further than this; that is all. Justice shall be done to the prisoners; and conviction shall not be obtained if I can help it. I repeat my objection to these interruptions. "Anstey, of course, had his nerves frayed as usual, and was in a most bellicose mood. When the prosecution counsel raised an objection to a question put by Anstey, Anstey observed, "no doubt, every objection will be made that mediocrity can invent and complaisance will allow." At a later stage, the judge addressing Anstey said, "if you insist on interrupting the proceedings, I shall have to fine you." Anstey: " If you fine me, I shall take the opinion of another court."

In his address to the jury, Anstey's plea was that if a trespasser builds upon the land of another person, that other has the right to pull down the structure. Referring to the withdrawal of the prosecution against various persons in the High Court and in the police court, Anstey observed that altogether 32 accused had been discharged in the two courts, due to "egregious and monstrous blunders" in identification. The main point which he urged upon the jury was, that the police had acted in a most tactless, provoking and high-handed manner, and were themselves to blame for any disturbance that had taken place. He made severe strictures on the conduct of the police officers, condemning the partisan behaviour of Brown, describing McDermott's conduct as "shamelessness which he could have only acquired since joining the police force". He dubbed Brown as unscrupulous; and the Commissioner himself as "a vain, weak, and imperious man." There were allegations that Souter himself had behaved in a very tactless and provocative manner, entering the precincts of the Towers On horseback, which led to considerable excitement among the Parsi crowd gathered there. Anstey wound up with the peroration, "your verdict will either be quoted for evermore hereafter in Bombay, as a precedent for every kind of tyranny, usurpation and injustice on the part of the police, or it will be applauded and appealed to as a great constitutional precedent."

The jury after taking time to consider their verdict brought in a unanimous verdict of not guilty against all the accused.

In those days, it seems, the Bombay High Court followed the British practice of locking up the jury in a room, until they reached unanimity in their verdict. There was a story that the Parsi juror, who was a big-built, burly man, refused to budge from his place, unless all the accused were acquitted; and ultimately tired out his co-jurors into agreeing to a unanimous verdict of not guilty as regards all the accused.

Anstey's long, successful, stormy, and colourful career at the Bombay Bar ended with this memorable case. It was long remembered in Bombay as one of the most striking and spectacular of his forensic triumphs, due mainly to his fearless and tenacious advocacy of the cause of his clients. He died shortly after, leaving a name which was commemorated in a grateful song, sung by Parsis at weddings and other auspicious occasions, for years after his death.

message 10:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Nov 23, 2014 06:21PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Paul Scott’s Raj Quartet: The English War and Peace

http://www.theimaginativeconservative...

Source: The Imaginative Conservative

http://www.theimaginativeconservative...

Source: The Imaginative Conservative

message 13:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Nov 23, 2014 06:28PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Ellen And Jim Have A Blog, Two

In solitude we have our dreams to oursevles, and in company we agree to dream in concert — Samuel Johnson, Idler 32: books, films, art, music, culture

http://ellenandjim.wordpress.com/2009...

In solitude we have our dreams to oursevles, and in company we agree to dream in concert — Samuel Johnson, Idler 32: books, films, art, music, culture

http://ellenandjim.wordpress.com/2009...

Some interesting art work from The Folio Society related to book 3:

http://www.finncampbellnotman.com/ind...

http://www.finncampbellnotman.com/ind...

Harvard Review on line:

BEHIND PAUL SCOTT’S RAJ QUARTET: A LIFE IN LETTERS, VOLUMES I & II

by Paul Scott

edited by Janis Haswell

reviewed by Laura Albritton

June 3, 2013

http://harvardreview.fas.harvard.edu/...

by

by

Paul Scott

Paul Scott

BEHIND PAUL SCOTT’S RAJ QUARTET: A LIFE IN LETTERS, VOLUMES I & II

by Paul Scott

edited by Janis Haswell

reviewed by Laura Albritton

June 3, 2013

http://harvardreview.fas.harvard.edu/...

by

by

Paul Scott

Paul Scott

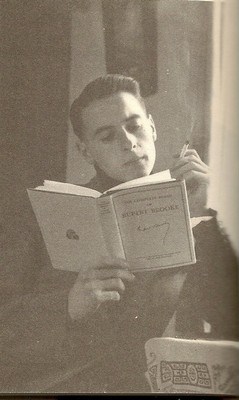

The Origins of Paul Scott's Vast Masterpiece

The epic of colonial India

By Peter Green

I first met Paul Scott at Firpo’s bar on Chowringhee in Calcutta in 1944. I was an NCO in what was euphemistically described as “Special Duties,” that is, intelligence, but more often meant taking on any odd job for which no one else could be found; Paul was an air supply captain who had been commissioned into the Service Corps, unkindly known to the Rifle Brigade or the Gurkhas as, in the words of his biographer Hilary Spurling, “the Rice Corps, Flying Grocers, or Jam Stealers and generally considered to be about as low as it was possible to get in the Indian Army.” We eyed each other’s shoulder-chips with sympathy over drinks, and got on extremely well. I did wonder at the time whether he might not have been trying to pick me up, a suspicion that Spurling’s biography and the new collection of Scott’s letters have done nothing to dispel.

A decade later, with Cambridge behind me, I was trying to break into the London literary world, and decided I needed an agent. Summoned for an interview at the firm then known as Pearn, Pollinger and Higham, I found myself facing, across a desk, an elegantly suited gentleman who—I suddenly realized at about the same moment as the penny dropped for him—was none other than my Rice Corps bar companion. We both exploded with laughter, and I became his client on the spot.

So began a literary friendship that lasted, in person or by correspondence, until Paul’s tragically early death in 1978. For six years, until he gave up his job to become a full-time novelist in 1960, Paul was my literary agent. We exchanged innumerable critical letters1 (quite a few of which have found their way into Janis Haswell’s collection) about work in progress, together with a kind of running commentary on the rare splendors and all-too-frequent miseries, mostly financial, of the writer’s life. We lunched with each other regularly at Paul’s favorite Soho tavern, the Dog and Duck. He was pleasant, competent, sardonic: nice to know, but nothing out of the ordinary. When I moved to the country and came up to town on weekly flying visits, I occasionally stayed with him and his wife, Penny, and their two school-age daughters in Hampstead Garden Suburb.

The fictional world of British India that he conjured up became virtually his sole reality.

But from 1963 until 1971, my family and I were living in Greece, and after that I took up an academic post in the United States, so that during this highly important late period of his career my friendship with Paul was in essence restricted to letters. It was then, in the early 1960s, that Paul finally discovered his great theme—the twilight and eclipse of the British Raj in India—and retreated further and further, during the decade that it took him to sweat out the four long volumes that emerged as The Raj Quartet, into a kind of creative solitude where the fictional world of British India that he conjured up became, more and more as time went on, virtually his sole reality.

The physical and emotional cost was appalling. It was, essentially, as his daughter Carol saw, the prime cause of his alienation from Penny, the break-up of his long marriage. By the end he was (as he told a doctor) eating little, sleeping less, and drinking a quart of vodka a day. When I finally saw him again, after the completion of the Quartet—we had invited him to lecture at the University of Texas—I was shocked by the change in his appearance. In 1975, though still only in his mid-fifties, he was a dying man, and knew it. The completion of that vast and complex project had exacted a horrendous price, of which perhaps the saddest aspect was that Paul never lived to enjoy the fame and success that it brought him.

Paul himself had put it on record, very early, “that I mean & intend to become a great artist if I possibly can be.” Yet there is nothing about his early suburban life—or, indeed, much of his pre-Quartet fiction—that presages the power and the scope of the Indian tetralogy. The son of a commercial artist (the family claimed descent from the engraver Thomas Bewick) who fell on hard times, he was removed from his private school—a far from classy one—at the age of fourteen and set to train as an accountant. He began writing poems and plays that were, as he agreed later in life, better forgotten. The turning point was his army career, which took him to Bengal, Imphal, and Malaya; but the seed then sown took years to come to fruition, and not before several not-quite-right attempts, such as Six Days in Marapore and The Chinese Love Pavilion, had been painstakingly hammered out. After the war, having qualified as an accountant, he got a job keeping the books for a new publishing firm, and from there moved on to the literary agency where I met him again. All the time he was writing, and fiction by now was slowly beginning to oust poems and plays.

Paul himself often said that his life, like that of most writers, was a fundamentally dull one. When I started on the first volume of Janis Haswell’s collection of his correspondence, which begins in 1940 with him as an army recruit, it was in the hope of proving him modestly wrong. At first I was disappointed. Paul was still plugging away, when he had time from army duties, at what sound like terrible plays and even worse poems, criticized and dissected at tedious length in correspondence with Clive Sansom. His literary standards were relentlessly middle-class: “I wish the rain wouldn’t look so much like a short story by Maugham. Nobody else has a chance to do anything literary with that man’s shadow haunting the scene.” The only unexpected discovery was his open discussion of his youthful homosexuality (often managed in the third person: he called his alter ego Ivan Kapinsky) with friends such as Ruth Sansom.

The larger part of Haswell’s first volume deals with Paul’s post-war life as a literary agent and a working novelist: the years when I knew him best. What strikes me now is how completely professional matters, and the correspondence dealing with them, occupied almost his entire waking life: even the lunches were literary, and almost all his friends were, one way or another, in the book trade. As everyone agreed, he was a brilliant agent, who took endless pains over his clients. Many of these letters deal with critical discussion of manuscripts, his own or those of others, which for those outside the charmed circle will make tough reading. (I suspect Haswell inserted so many of them for the benefit of English professors teaching Scott’s fiction.) As Paul wrote in 1960, “The bloody trouble is we are only alive when we’re half dead trying to get a paragraph right.” When he decides to give up the agency and become a full-time writer, there is more about his own problems and less about those of his clients: but the ingrown London world of novelists, reviewers, publishers, and agents remains essentially unaltered.

The turning point came in 1964, when his London publisher, Heinemann, with what can only be regarded, in hindsight, as remarkable acumen, arranged for his return to India on a six-week visit. (Two more such trips were arranged during the years when he was engaged with the Quartet.) He was looked after in Bombay by Dorothy Ganapathy, who became a lifelong friend. He stayed for over a week with his wartime havildar (sergeant), in a rural village in Andhra Pradesh, where he experienced culture-shock in its most extreme form. While in Calcutta he met Neil Ghosh, product of a British public-school education, who became the model for Hari Kumar in the Quartet. Best of all, he found a correct diagnosis of the amoebiasis that he had contracted during the war, with its legacy of “lassitude, depression, insomnia, mood swings, and lack of concentration.” For this he sought, and got, curative treatment in Paris. Almost immediately, in the surge of health that followed, his renewed acquaintance with India fresh in his mind, he began to write The Jewel in the Crown.

This, the first of the four novels that go to make up the Quartet, is set in 1942: the year of the British defeat by the Japanese in Burma and points east, the realization by Hindus and Muslims that the gods of the Raj were by no means omnipotent. We meet several of the main characters, whose lives are impacted, for good or ill, by these events, such as Edwina Crane, the elderly missionary, whose sense of progress and colonial idealism is left in tatters after a riot that kills the young Hindu teacher with whom she works, and leaves her holding his dead hand in the rain beside her burnt-out car. We sit in on the striated prejudices of the Europeans-only club, meet socially impeccable Brahmins such as Lady Chatterjee as well as the Eurasian half-castes who talk in what I remember being referred to, unkindly but accurately, as “Bombay Welsh,” and make pathetic claims to have come out from Brighton or Manchester: the simple fact of the existence of foreign rulers and native subjects is seen to penetrate and falsify all human relationships.

The most vivid, violent, and memorable of these relationships is that between the Indian Hari Kumar—resident in England almost all his life, public-school educated, speaking no Hindi or Urdu, and abruptly returned to Mayapore—and Daphne Manners, fresh out from home, the awkward big-boned niece of a former governor. They fall in love; they stumble through the dreadful minefield of social and racial taboos, and Daphne is raped by a bunch of out-of-town Hindu thugs while making love to Hari in the Bibighar Gardens at night. She cannot admit the affair with Hari without getting him into appalling trouble; but the lies involved are instantly picked up by Ronald Merrick, the district superintendent of police, a major malign figure throughout the Quartet, a lower-middle-class English provincial who is a steely upholder of the colonial status quo that has let him rise to a position of real authority in India. He has also proposed marriage to Daphne, and is all too ready to nail Hari Kumar for a serious offense. The repercussions of the rape in the Bibighar Gardens spread through the entire sequence, affecting not only the protagonists but everyone, English or Indian, civilian or military, who comes into contact with the case.

What has always astonished me about The Raj Quartet is its sense of sophisticated and total control of its gigantic scenario and highly varied characters. The four volumes constitute perfectly interlocking movements of a grand overall design. The politics are handled with an expertise that intrigues and never bores, and are always seen in terms of individuals. Though Paul always saw the inevitability, and the necessity, of an end to the British occupation, and exploitation, of India, he still could see, and sympathize with, the odd virtues that the Raj bred in its officers. No one—certainly not E. M. Forster—has ever produced a subtler, more nuanced, picture of the Raj in action during its last fraught years, or of the seething, complex, and wildly disparate nationalist forces arrayed against it.

The second volume of Scott’s letters takes over as this great novel sequence begins to be written, and inevitably it contains far more than its predecessor to quicken the general reader’s interest. Other novelists will not be surprised to learn that many experiences in the The Raj Quartet that befall its various characters actually happened to Paul himself. “Madame Bovary, c’est moi,” as Flaubert famously declared. There are changes of opinion: the project starts as one novel, grows to three in the middle of The Day of the Scorpion, and becomes a quartet only when The Towers of Silence threatens to become too unwieldy—yet the larger whole never loses its overall cohesion.

The epic of colonial India

By Peter Green

I first met Paul Scott at Firpo’s bar on Chowringhee in Calcutta in 1944. I was an NCO in what was euphemistically described as “Special Duties,” that is, intelligence, but more often meant taking on any odd job for which no one else could be found; Paul was an air supply captain who had been commissioned into the Service Corps, unkindly known to the Rifle Brigade or the Gurkhas as, in the words of his biographer Hilary Spurling, “the Rice Corps, Flying Grocers, or Jam Stealers and generally considered to be about as low as it was possible to get in the Indian Army.” We eyed each other’s shoulder-chips with sympathy over drinks, and got on extremely well. I did wonder at the time whether he might not have been trying to pick me up, a suspicion that Spurling’s biography and the new collection of Scott’s letters have done nothing to dispel.

A decade later, with Cambridge behind me, I was trying to break into the London literary world, and decided I needed an agent. Summoned for an interview at the firm then known as Pearn, Pollinger and Higham, I found myself facing, across a desk, an elegantly suited gentleman who—I suddenly realized at about the same moment as the penny dropped for him—was none other than my Rice Corps bar companion. We both exploded with laughter, and I became his client on the spot.

So began a literary friendship that lasted, in person or by correspondence, until Paul’s tragically early death in 1978. For six years, until he gave up his job to become a full-time novelist in 1960, Paul was my literary agent. We exchanged innumerable critical letters1 (quite a few of which have found their way into Janis Haswell’s collection) about work in progress, together with a kind of running commentary on the rare splendors and all-too-frequent miseries, mostly financial, of the writer’s life. We lunched with each other regularly at Paul’s favorite Soho tavern, the Dog and Duck. He was pleasant, competent, sardonic: nice to know, but nothing out of the ordinary. When I moved to the country and came up to town on weekly flying visits, I occasionally stayed with him and his wife, Penny, and their two school-age daughters in Hampstead Garden Suburb.

The fictional world of British India that he conjured up became virtually his sole reality.

But from 1963 until 1971, my family and I were living in Greece, and after that I took up an academic post in the United States, so that during this highly important late period of his career my friendship with Paul was in essence restricted to letters. It was then, in the early 1960s, that Paul finally discovered his great theme—the twilight and eclipse of the British Raj in India—and retreated further and further, during the decade that it took him to sweat out the four long volumes that emerged as The Raj Quartet, into a kind of creative solitude where the fictional world of British India that he conjured up became, more and more as time went on, virtually his sole reality.

The physical and emotional cost was appalling. It was, essentially, as his daughter Carol saw, the prime cause of his alienation from Penny, the break-up of his long marriage. By the end he was (as he told a doctor) eating little, sleeping less, and drinking a quart of vodka a day. When I finally saw him again, after the completion of the Quartet—we had invited him to lecture at the University of Texas—I was shocked by the change in his appearance. In 1975, though still only in his mid-fifties, he was a dying man, and knew it. The completion of that vast and complex project had exacted a horrendous price, of which perhaps the saddest aspect was that Paul never lived to enjoy the fame and success that it brought him.

Paul himself had put it on record, very early, “that I mean & intend to become a great artist if I possibly can be.” Yet there is nothing about his early suburban life—or, indeed, much of his pre-Quartet fiction—that presages the power and the scope of the Indian tetralogy. The son of a commercial artist (the family claimed descent from the engraver Thomas Bewick) who fell on hard times, he was removed from his private school—a far from classy one—at the age of fourteen and set to train as an accountant. He began writing poems and plays that were, as he agreed later in life, better forgotten. The turning point was his army career, which took him to Bengal, Imphal, and Malaya; but the seed then sown took years to come to fruition, and not before several not-quite-right attempts, such as Six Days in Marapore and The Chinese Love Pavilion, had been painstakingly hammered out. After the war, having qualified as an accountant, he got a job keeping the books for a new publishing firm, and from there moved on to the literary agency where I met him again. All the time he was writing, and fiction by now was slowly beginning to oust poems and plays.

Paul himself often said that his life, like that of most writers, was a fundamentally dull one. When I started on the first volume of Janis Haswell’s collection of his correspondence, which begins in 1940 with him as an army recruit, it was in the hope of proving him modestly wrong. At first I was disappointed. Paul was still plugging away, when he had time from army duties, at what sound like terrible plays and even worse poems, criticized and dissected at tedious length in correspondence with Clive Sansom. His literary standards were relentlessly middle-class: “I wish the rain wouldn’t look so much like a short story by Maugham. Nobody else has a chance to do anything literary with that man’s shadow haunting the scene.” The only unexpected discovery was his open discussion of his youthful homosexuality (often managed in the third person: he called his alter ego Ivan Kapinsky) with friends such as Ruth Sansom.

The larger part of Haswell’s first volume deals with Paul’s post-war life as a literary agent and a working novelist: the years when I knew him best. What strikes me now is how completely professional matters, and the correspondence dealing with them, occupied almost his entire waking life: even the lunches were literary, and almost all his friends were, one way or another, in the book trade. As everyone agreed, he was a brilliant agent, who took endless pains over his clients. Many of these letters deal with critical discussion of manuscripts, his own or those of others, which for those outside the charmed circle will make tough reading. (I suspect Haswell inserted so many of them for the benefit of English professors teaching Scott’s fiction.) As Paul wrote in 1960, “The bloody trouble is we are only alive when we’re half dead trying to get a paragraph right.” When he decides to give up the agency and become a full-time writer, there is more about his own problems and less about those of his clients: but the ingrown London world of novelists, reviewers, publishers, and agents remains essentially unaltered.

The turning point came in 1964, when his London publisher, Heinemann, with what can only be regarded, in hindsight, as remarkable acumen, arranged for his return to India on a six-week visit. (Two more such trips were arranged during the years when he was engaged with the Quartet.) He was looked after in Bombay by Dorothy Ganapathy, who became a lifelong friend. He stayed for over a week with his wartime havildar (sergeant), in a rural village in Andhra Pradesh, where he experienced culture-shock in its most extreme form. While in Calcutta he met Neil Ghosh, product of a British public-school education, who became the model for Hari Kumar in the Quartet. Best of all, he found a correct diagnosis of the amoebiasis that he had contracted during the war, with its legacy of “lassitude, depression, insomnia, mood swings, and lack of concentration.” For this he sought, and got, curative treatment in Paris. Almost immediately, in the surge of health that followed, his renewed acquaintance with India fresh in his mind, he began to write The Jewel in the Crown.

This, the first of the four novels that go to make up the Quartet, is set in 1942: the year of the British defeat by the Japanese in Burma and points east, the realization by Hindus and Muslims that the gods of the Raj were by no means omnipotent. We meet several of the main characters, whose lives are impacted, for good or ill, by these events, such as Edwina Crane, the elderly missionary, whose sense of progress and colonial idealism is left in tatters after a riot that kills the young Hindu teacher with whom she works, and leaves her holding his dead hand in the rain beside her burnt-out car. We sit in on the striated prejudices of the Europeans-only club, meet socially impeccable Brahmins such as Lady Chatterjee as well as the Eurasian half-castes who talk in what I remember being referred to, unkindly but accurately, as “Bombay Welsh,” and make pathetic claims to have come out from Brighton or Manchester: the simple fact of the existence of foreign rulers and native subjects is seen to penetrate and falsify all human relationships.

The most vivid, violent, and memorable of these relationships is that between the Indian Hari Kumar—resident in England almost all his life, public-school educated, speaking no Hindi or Urdu, and abruptly returned to Mayapore—and Daphne Manners, fresh out from home, the awkward big-boned niece of a former governor. They fall in love; they stumble through the dreadful minefield of social and racial taboos, and Daphne is raped by a bunch of out-of-town Hindu thugs while making love to Hari in the Bibighar Gardens at night. She cannot admit the affair with Hari without getting him into appalling trouble; but the lies involved are instantly picked up by Ronald Merrick, the district superintendent of police, a major malign figure throughout the Quartet, a lower-middle-class English provincial who is a steely upholder of the colonial status quo that has let him rise to a position of real authority in India. He has also proposed marriage to Daphne, and is all too ready to nail Hari Kumar for a serious offense. The repercussions of the rape in the Bibighar Gardens spread through the entire sequence, affecting not only the protagonists but everyone, English or Indian, civilian or military, who comes into contact with the case.

What has always astonished me about The Raj Quartet is its sense of sophisticated and total control of its gigantic scenario and highly varied characters. The four volumes constitute perfectly interlocking movements of a grand overall design. The politics are handled with an expertise that intrigues and never bores, and are always seen in terms of individuals. Though Paul always saw the inevitability, and the necessity, of an end to the British occupation, and exploitation, of India, he still could see, and sympathize with, the odd virtues that the Raj bred in its officers. No one—certainly not E. M. Forster—has ever produced a subtler, more nuanced, picture of the Raj in action during its last fraught years, or of the seething, complex, and wildly disparate nationalist forces arrayed against it.

The second volume of Scott’s letters takes over as this great novel sequence begins to be written, and inevitably it contains far more than its predecessor to quicken the general reader’s interest. Other novelists will not be surprised to learn that many experiences in the The Raj Quartet that befall its various characters actually happened to Paul himself. “Madame Bovary, c’est moi,” as Flaubert famously declared. There are changes of opinion: the project starts as one novel, grows to three in the middle of The Day of the Scorpion, and becomes a quartet only when The Towers of Silence threatens to become too unwieldy—yet the larger whole never loses its overall cohesion.

Continued:

In 1968, Paul opines that, as he grows older, he becomes “more and more convinced that literature isn’t really a fit subject for academic study.” Yet a decade later, he astonishes himself by emerging as a brilliant, and inspired, university teacher in the States. Those who claim he was short on humor should read his letters to his daughter Carol, which contain the adventures (with hilarious illustrative sketches) of one Abu Ben Grottso, Camille the Camel, and the sultry Scarlet Sahara. He meets Stevie Smith at a party and drives her home: “What a journey!” he reports. “I’ve not laughed so much in years.” Surprisingly, he turns out to be a close observer of natural life: in a letter to Freya Stark he talks of the creatures—hedgehogs, foxes, rabbits, magpies, a sparrowhawk—that he watches from his study window. Confronted by an early dissertation on his work, he addresses himself in the mirror: “You mean that’s what you were saying?” He regales his daughter Sally, only a year before his death, with four detailed, and expert, pages on how to cook chef-style curry and chicken pulao.

There is nothing here to indicate any fundamental road-to-Damascus change from the efficient agent and struggling, if ironic, littérateur from the London suburbs whom I knew as my friend and fellow-novelist in the late 1950s. We critiqued each other’s fiction: his was good, but not in any way really exceptional. By the time he was well into The Jewel in the Crown, I had left for Greece, and never saw the manuscript. In October 1965, he wrote me—already clearly worried about money—that “I think my future largely depends now on what happens to my mammoth novel (about the Indian rebellion of 1942).” He had said much the same thing in 1962 about The Birds of Paradise, which I had read: a fictional memoir by an Anglo-Indian raised in India, schooled in England, and scarred as much by heartache as by time spent in a Japanese POW camp. This, I now see, was a trial run for the The Raj Quartet, though I very much doubt that its author knew it at the time. Maugham still cast a long shadow over these pages. From Haswell’s selection it also emerges that Paul was already drinking very heavily, and had at one time at least contemplated suicide.

The Quartet remains a tour de force virtu-ally without rivals. The question is, how?

I have gone into these details in order to highlight the absolute astonishment I felt when I first read The Jewel in the Crown, and then, with mounting excitement, each subsequent volume of what was to become The Raj Quartet. The style, tone, depth, range, and human understanding had all, at a stroke, undergone a quite extraordinary, and enriching, metamorphosis. The perception of character that had previously restricted itself, in essence, to Scott’s own literary suburbia here suddenly blossomed into a breadth of understanding that had no trouble with a psychopathic police superintendent, an aristocratic Rajput matriarch, an émigré Russian homosexual acting as chief minister in an Indian princely state, a highly sophisticated Muslim politician, two elderly spinster missionaries, and a wide assortment of military families brought up, generation after generation, to serve the Raj.

The apparent knowledge of cantonment life, of high-level Anglo-Indian diplomacy, of the inner thoughts and emotional problems of both British administrators and Muslim or Hindu nationalists went far beyond what could be learned by research (of which, it turned out, Paul did a great deal).2 What really amazed was the way he never put a foot wrong psychologically over either caste or gender, so that an old Indian Civil Service luminary such as Sir Herbert Thompson, on reading A Division of the Spoils, instantly assumed that it must have been written by one of his former colleagues under a pseudonym. As Spurling says, when the truth was out and Paul had his first of many lunches with the Thompsons, he felt “the strange sensation of stepping through the looking-glass into a world he had so far projected only in his imagination.”

The Quartet remains a tour de force virtually without rivals. The question is, how? How did this middle-class suburbanite—who left school at fourteen, had no experience of diplomacy or the civil service, in India or anywhere else, and never set foot inside a British university in his life—suddenly, after a solid but hitherto no more than middling literary career, acquire the vision that brought the world of the fading Raj to unforgettable life, in a quartet of novels that for range and power have been compared to Tolstoy? Suggestions have not been wanting, most notably that his experience on the wrong side of the rigid social divisions operating in pre-war London suburbia gave him a sharpened insight into both native caste distinctions and the even more absolute British color-bar that he found in India. Others have pointed to his sexual ambiguity (and probable repression of his homosexual side after a bad experience, perhaps drawn on for Corporal Pinker’s dealings with Colonel Merrick in A Division of the Spoils). There may be some truth in both of these theories, but since both stem from Paul’s early life, why did they not have the same transforming effect on his early fiction as they are alleged to have done on The Raj Quartet? The difference is as total, and as extraordinary, as the still not fully understood process by which a chrysalis becomes a butterfly.

In Paul’s case, it seems to have been a visitation akin to speaking in tongues, a literal possession; and this kind of possession can be dangerous. It perhaps explains what his wife misinterpreted as his “expression of hate” when she interrupted him. What he primarily felt was the agony of loss at being brought back out of an all-embracing cocoon: a total creative world in which he had been granted complete insight, social and psychological, into every character and action. After about a million words of this, he was an alcoholic wreck, and small wonder. It is especially interesting that Staying On, the short and charming coda4 to the magnum opus of the The Raj Quartet, shows no signs of this kind of possession, willed or involuntary: it was written fast and enjoyably, and reads like it, a deft and sympathetic jeu d’esprit created comfortably from the immense experience, and ample detritus, of its great predecessors. “What will survive of us is love,” said Larkin. Staying On, written after Penny had left him, is a wonderful exemplification of that wisdom.

Not long ago, after a lapse of some years, I re-read them all, and was struck, first and foremost, at how readable—even the disquisition on Hindu political cartoons!—the entire sequence was. “I am large,” wrote Whitman. “I contain multitudes.” Paul’s magnum opus has the same generous, almost Dickensian capacity. There are the great set-pieces—Daphne Manners’s report to her aunt on the rape in the Bibighar Gardens (I don’t agree that Paul was trying to outsmart Forster here); Sir George Malcolm’s interview with Mohammad Ali Khan; the interrogation of Hari Kumar by Nigel Rowan and Ramaswamy Gopal, with Lady Manners as unseen witness; Merrick’s report from his hospital bed to Sarah Layton of how Teddy Bingham died; Barbie and Mabel at the Pankot Rifles party; Mohammed Ali Kasim’s fraught meeting with his son Sayed, a prisoner after having served in the anti-British Indian National Army.