The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Martin Chuzzlewit

>

MC, Chp. 16-17

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Chapter 17

It’s been quite some time that Martin has left Mark to his own devices – with their luggage – now, and our narrator points out that it is characteristic of our hero not to have thought of his friend all that time and that now he recalls him to mind in a rather off-handed manner. When Dr. Bevan suggest they should take a walk, Martin asks him to wend their way towards the office of the New York Rowdy Journal and pick up Mark – because Martin ”would be glad to get this piece of business off his mind.” Interesting choice of words, isn’t it?

On their way to the office, Dr. Bevan tells Martin a little bit about himself, e.g. that he is a physician from Massachusetts and that he by no means likes being in busy places like New York. He also lambasts the self-complacency of his compatriots and states that Americans have two advantages over Europe, namely that 1) they did not have such a bloody history, having left out the Middle Ages and all that, and 2) their country is as yet not overpopulated. Considering this, they have not played out their advantages for the best, as the doctor says. For all his criticism, he also sees the good points of his country, for instance the superiority of their educational system over that of Great Britain, who has one of the worst educational systems, according to Dr. Bevan. The doctor also says that there are a great many Americans who are alive to the shortcomings of their country and who address them, but as a rule, no American person really likes non-Americans to criticize the U.S.

QUESTIONS

Is it Dickens talking through Dr. Bevan here? And if so, did he really think that the history of the U.S. is less bloody than that of European countries? Maybe, a little reading of Richard Slotkin would have done Dr. Bevan good, but that is, of course, an anachronistic wish.

They also spend some time talking about Martin’s plans, and Bevan finally says that he does not really see great chances of success for Martin as an architect in New York, and not to wind up with too disillusioning a statement, he says that he will make enquiries as to other places where Martin can follow his profession with success. When the two men arrive at the office-door of the New York Rowdy Journal, they find Mark ensconced with the luggage, but apparently at ease. He is not alone, either, there being an old black man waiting with him – he will later be introduced as an ex-slave named Cicero – to help him take the luggage to the boarding house. First of all, Mark informs Martin about the fate of the wife and the children: They were awaited on their arrival by the husband, or, as Mark puts it, rather by the shadow of the shadow of the husband, for the man has been falling from one fever into another since he bought land that turned out swampland and was not only of limited use as farmland but also insalubrious to live on. Now, the family are reunited, but Mark fears that sooner or later, the husband will die. Then the men’s attention turns to Mark’s new friend, the ex-slave: Mark tells Martin about Cicero’s life – and he is so sensitive that he tells his master not to look at Cicero while he is talking about him: We learn that Cicero’s life was usually one of torture and cruelty, and that his whole body can bear witness thereof. When he had a kinder master, he managed to save so much money as to buy himself off, which was relatively easy since he was by then quite old and weak. His next project is described by Mark in the following words:

”’[…] And now he’s a–saving up to treat himself, afore he dies, to one small purchase — it’s nothing to speak of. Only his own daughter; that’s all!’ cried Mr Tapley, becoming excited. ‘Liberty for ever! Hurrah! Hail, Columbia!’”

QUESTIONS

Mark uses pretty jocular expressions to talk about the plight of that family. He says, for instance, that the wife found “the remains” of her husband, and that on being reunited they looked as happy as though there were going straight to Heaven, which Mark thinks they will very soon. – In a way, these expressions seem quite heartless and cynical. Why, do you think, does Mark use such airy language?

When he talks about the slave, Mark is getting quite angry, obviously, as his bitter exclamation shows, and Martin has to hush him up. – Why might Dickens have brought up the question of slavery here?

Seeing how bitter and indignant Mark is because of Cicero, and the system of slavery, and how little he is given to mince his words, he insists that the young man accompany them on their way lest he will run into severe problems on his own. So, Cicero is to carry the luggage to Major Pawkins’s on his own. After a sightseeing tour of three hours, Martin would like to go back to the boarding house, but the doctor insists on their going first to see a friend of his, and our narrator makes much of the fact that for once, Martin allows another man’s wishes to take precedence over his own:

”So travelling had done him that much good, already.”

Hmmm, is there going to be further improvement in Martin then?

Martin is now introduced into the Norris family, who at first sight is pleasant enough but who is also used as a vehicle of the author’s intention to criticize the U.S. and its way of life. The Norris people are an extremely contradictory bunch: They uphold the principle of equality but at the same time, they are well-acquainted with lots of English noble families and eager to hear and talk about these people. They are also confessed abolitionists, but they are clearly racist in that they regard black people as so ludicrous creatures that nothing concerning them can be taken seriously, really. They also criticize European prejudices and European tendencies to divide societies into classes, orders, and such like, and at the same time they look down upon those of their neighbours who adhere to another Christian church than they do. When the arrival of another pompous military man, a General Fladdock, it comes out that Martin has travelled in the steerage with other poor people, the Norrises regard themselves as scandalized at having unwittingly granted access into their genteel circle to a man without a penny (or cent) to himself. Martin, seeing their unfriendly and cold reactions to this disclosure, takes his cue and walks away.

When they arrive at the boarding house, there are three ladies in the guestroom, drinking tea. In the course of their conversation, they let out what lectures they attend. It’s all to do with philosophy – from the Philosophy of Government to the Philosophy of Vegetables (I don’t know if cooked or raw). When Martin says that their lives must be busy what with dividing their time between their education and their domestic duties, he once again has put his foot in it and earns cold shoulders from everyone. His friend Bevan explains:

”Mr Bevan informed him that domestic drudgery was far beneath the exalted range of these Philosophers, and that the chances were a hundred to one that not one of the three could perform the easiest woman’s work for herself, or make the simplest article of dress for any of her children.”

QUESTIONS

This latter thing seems to be Dickens’s pet peeve – just think of Mrs. Jellyby: Women who spend their time outside the domestic sphere, and the whole household going to seeds all the while. Dear me! The horror, the horror! Again, the chapter is devoted to running down America and its inhabitants in general, and Dickens pulls no punches in his criticism: Slavery, hypocrisy, narrow-mindedness, snobbery, and women who don’t look after their children and their households! How must the reading public have taken it? Were there any differences according to what side of the Atlantic these chapters were read? And talking of hypocrisy: What is the difference between the hypocrisy we find in the American chapters, and Mr. Pecksniff’s hypocrisy, which even earns him the praise of Anthony?

Poor old Martin! He is evidently disillusioned and glum now, and it is quite a blessing that Mark acquaints him with a novel drink, a so-called sherry cobbler. Another blessing may be that the final sentence of the chapter tells us that we are going to find ourselves back in England in the next instalment.

It’s been quite some time that Martin has left Mark to his own devices – with their luggage – now, and our narrator points out that it is characteristic of our hero not to have thought of his friend all that time and that now he recalls him to mind in a rather off-handed manner. When Dr. Bevan suggest they should take a walk, Martin asks him to wend their way towards the office of the New York Rowdy Journal and pick up Mark – because Martin ”would be glad to get this piece of business off his mind.” Interesting choice of words, isn’t it?

On their way to the office, Dr. Bevan tells Martin a little bit about himself, e.g. that he is a physician from Massachusetts and that he by no means likes being in busy places like New York. He also lambasts the self-complacency of his compatriots and states that Americans have two advantages over Europe, namely that 1) they did not have such a bloody history, having left out the Middle Ages and all that, and 2) their country is as yet not overpopulated. Considering this, they have not played out their advantages for the best, as the doctor says. For all his criticism, he also sees the good points of his country, for instance the superiority of their educational system over that of Great Britain, who has one of the worst educational systems, according to Dr. Bevan. The doctor also says that there are a great many Americans who are alive to the shortcomings of their country and who address them, but as a rule, no American person really likes non-Americans to criticize the U.S.

QUESTIONS

Is it Dickens talking through Dr. Bevan here? And if so, did he really think that the history of the U.S. is less bloody than that of European countries? Maybe, a little reading of Richard Slotkin would have done Dr. Bevan good, but that is, of course, an anachronistic wish.

They also spend some time talking about Martin’s plans, and Bevan finally says that he does not really see great chances of success for Martin as an architect in New York, and not to wind up with too disillusioning a statement, he says that he will make enquiries as to other places where Martin can follow his profession with success. When the two men arrive at the office-door of the New York Rowdy Journal, they find Mark ensconced with the luggage, but apparently at ease. He is not alone, either, there being an old black man waiting with him – he will later be introduced as an ex-slave named Cicero – to help him take the luggage to the boarding house. First of all, Mark informs Martin about the fate of the wife and the children: They were awaited on their arrival by the husband, or, as Mark puts it, rather by the shadow of the shadow of the husband, for the man has been falling from one fever into another since he bought land that turned out swampland and was not only of limited use as farmland but also insalubrious to live on. Now, the family are reunited, but Mark fears that sooner or later, the husband will die. Then the men’s attention turns to Mark’s new friend, the ex-slave: Mark tells Martin about Cicero’s life – and he is so sensitive that he tells his master not to look at Cicero while he is talking about him: We learn that Cicero’s life was usually one of torture and cruelty, and that his whole body can bear witness thereof. When he had a kinder master, he managed to save so much money as to buy himself off, which was relatively easy since he was by then quite old and weak. His next project is described by Mark in the following words:

”’[…] And now he’s a–saving up to treat himself, afore he dies, to one small purchase — it’s nothing to speak of. Only his own daughter; that’s all!’ cried Mr Tapley, becoming excited. ‘Liberty for ever! Hurrah! Hail, Columbia!’”

QUESTIONS

Mark uses pretty jocular expressions to talk about the plight of that family. He says, for instance, that the wife found “the remains” of her husband, and that on being reunited they looked as happy as though there were going straight to Heaven, which Mark thinks they will very soon. – In a way, these expressions seem quite heartless and cynical. Why, do you think, does Mark use such airy language?

When he talks about the slave, Mark is getting quite angry, obviously, as his bitter exclamation shows, and Martin has to hush him up. – Why might Dickens have brought up the question of slavery here?

Seeing how bitter and indignant Mark is because of Cicero, and the system of slavery, and how little he is given to mince his words, he insists that the young man accompany them on their way lest he will run into severe problems on his own. So, Cicero is to carry the luggage to Major Pawkins’s on his own. After a sightseeing tour of three hours, Martin would like to go back to the boarding house, but the doctor insists on their going first to see a friend of his, and our narrator makes much of the fact that for once, Martin allows another man’s wishes to take precedence over his own:

”So travelling had done him that much good, already.”

Hmmm, is there going to be further improvement in Martin then?

Martin is now introduced into the Norris family, who at first sight is pleasant enough but who is also used as a vehicle of the author’s intention to criticize the U.S. and its way of life. The Norris people are an extremely contradictory bunch: They uphold the principle of equality but at the same time, they are well-acquainted with lots of English noble families and eager to hear and talk about these people. They are also confessed abolitionists, but they are clearly racist in that they regard black people as so ludicrous creatures that nothing concerning them can be taken seriously, really. They also criticize European prejudices and European tendencies to divide societies into classes, orders, and such like, and at the same time they look down upon those of their neighbours who adhere to another Christian church than they do. When the arrival of another pompous military man, a General Fladdock, it comes out that Martin has travelled in the steerage with other poor people, the Norrises regard themselves as scandalized at having unwittingly granted access into their genteel circle to a man without a penny (or cent) to himself. Martin, seeing their unfriendly and cold reactions to this disclosure, takes his cue and walks away.

When they arrive at the boarding house, there are three ladies in the guestroom, drinking tea. In the course of their conversation, they let out what lectures they attend. It’s all to do with philosophy – from the Philosophy of Government to the Philosophy of Vegetables (I don’t know if cooked or raw). When Martin says that their lives must be busy what with dividing their time between their education and their domestic duties, he once again has put his foot in it and earns cold shoulders from everyone. His friend Bevan explains:

”Mr Bevan informed him that domestic drudgery was far beneath the exalted range of these Philosophers, and that the chances were a hundred to one that not one of the three could perform the easiest woman’s work for herself, or make the simplest article of dress for any of her children.”

QUESTIONS

This latter thing seems to be Dickens’s pet peeve – just think of Mrs. Jellyby: Women who spend their time outside the domestic sphere, and the whole household going to seeds all the while. Dear me! The horror, the horror! Again, the chapter is devoted to running down America and its inhabitants in general, and Dickens pulls no punches in his criticism: Slavery, hypocrisy, narrow-mindedness, snobbery, and women who don’t look after their children and their households! How must the reading public have taken it? Were there any differences according to what side of the Atlantic these chapters were read? And talking of hypocrisy: What is the difference between the hypocrisy we find in the American chapters, and Mr. Pecksniff’s hypocrisy, which even earns him the praise of Anthony?

Poor old Martin! He is evidently disillusioned and glum now, and it is quite a blessing that Mark acquaints him with a novel drink, a so-called sherry cobbler. Another blessing may be that the final sentence of the chapter tells us that we are going to find ourselves back in England in the next instalment.

Tristram wrote: "Dear Curiosities,

Oh my! This week’s reading is quite a heavy chunk to swallow in more ways than one, I think. First of all, we have merely two chapters again, which means that they drag quite a b..."

Well, we could compare the American boarding-house with Todgers’s, or the street people in America with those found in London, but I’m not sure that will get us anywhere.

We have with the chapters set in America a tale of two Dickens. The American public loved him, and certainly Dickens was aware of their adulation. Publicly, he responded with great enthusiasm to his hosts and those he met during his travels. We also know that Dickens planned to write a book about his travels to America after his return to England because he asked his friends in England to save his American letters to them as a memory aid for the book that turned out to be American Notes. This book has some rather harsh and pointed comments about his American experiences and recollections.

The initial chapters of Martin Chuzzlewit set in the United States are not complimentary. How and if Dickens will modify or tone down Martin and Mark’s reactions is yet to be seen. How much good nature and upbeat spirit does Mark have?

It is interesting to observe, however, that no future Dickens novel has main characters go to North America and be recorded in detail in any chapters of any novel.

Oh my! This week’s reading is quite a heavy chunk to swallow in more ways than one, I think. First of all, we have merely two chapters again, which means that they drag quite a b..."

Well, we could compare the American boarding-house with Todgers’s, or the street people in America with those found in London, but I’m not sure that will get us anywhere.

We have with the chapters set in America a tale of two Dickens. The American public loved him, and certainly Dickens was aware of their adulation. Publicly, he responded with great enthusiasm to his hosts and those he met during his travels. We also know that Dickens planned to write a book about his travels to America after his return to England because he asked his friends in England to save his American letters to them as a memory aid for the book that turned out to be American Notes. This book has some rather harsh and pointed comments about his American experiences and recollections.

The initial chapters of Martin Chuzzlewit set in the United States are not complimentary. How and if Dickens will modify or tone down Martin and Mark’s reactions is yet to be seen. How much good nature and upbeat spirit does Mark have?

It is interesting to observe, however, that no future Dickens novel has main characters go to North America and be recorded in detail in any chapters of any novel.

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 17

It’s been quite some time that Martin has left Mark to his own devices – with their luggage – now, and our narrator points out that it is characteristic of our hero not to have thought ..."

An interesting question about hypocrisy Tristram. Pecksniff’s form of hypocrisy is more refined, gentile, and tastefully wrapped in the English class system. American hypocrisy seems more open and unadorned. Either way, hypocrisy is a nasty bit of business.

Overt or covert? Dickens seems to be exploring and presenting a wide pattern of human behaviour in these first American chapters.

It’s been quite some time that Martin has left Mark to his own devices – with their luggage – now, and our narrator points out that it is characteristic of our hero not to have thought ..."

An interesting question about hypocrisy Tristram. Pecksniff’s form of hypocrisy is more refined, gentile, and tastefully wrapped in the English class system. American hypocrisy seems more open and unadorned. Either way, hypocrisy is a nasty bit of business.

Overt or covert? Dickens seems to be exploring and presenting a wide pattern of human behaviour in these first American chapters.

I thought these two chapters to be quite interesting, but also exhausting in a way, because of all the new characters that made their appearance.

I wonder, what is the significance of the family Mark just sent on their way to 'heaven'? There has been a bit too much investment in them to just let them disappear, I think. Same goes for the other characters that made their appearance here - what kind of role will they play in the rest of the novel? I mostly want to read on now, to find out.

And yes, hypocrisy has a big role in this novel. Everyone has some, or seems to have some, or should perhaps have some under the sircumstances.

I wonder, what is the significance of the family Mark just sent on their way to 'heaven'? There has been a bit too much investment in them to just let them disappear, I think. Same goes for the other characters that made their appearance here - what kind of role will they play in the rest of the novel? I mostly want to read on now, to find out.

And yes, hypocrisy has a big role in this novel. Everyone has some, or seems to have some, or should perhaps have some under the sircumstances.

Truthfully, as a modern American who loves Dickens, these chapters were difficult to read. I don't mind someone critiquing America (I critique America too!), it just kinda stinks to feel like one of your favorite authors may have secretly disliked you if you were to travel back in time and meet him. Never meet your heroes, they say!

Truthfully, as a modern American who loves Dickens, these chapters were difficult to read. I don't mind someone critiquing America (I critique America too!), it just kinda stinks to feel like one of your favorite authors may have secretly disliked you if you were to travel back in time and meet him. Never meet your heroes, they say! I am curious about the function Dr. Bevan serves. He seems like a really underdeveloped character at this moment? Dickens referred to him more frequently as "Martin's friend," rather than using his name. This almost made him a non-entity in my reading of these chapters. I had to keep flipping back in order to find his real name. I'm curious to see how his relationship with Martin will develop. Is Bevan actually going to be useful to Martin and his plans of obtaining wealth?

The New York Keyhole Reporter. I want pictures.

Martin better not fall over Tom, Mary, Pecksniff, or Westlock in America. I'll protest.

A sense of humor and a bottle of wine help me get though chapters like this.

Dickens is having fun with American eating "rituals." So different from the Brits. Heeheehee.

And Jefferson Brick's wife is a child. Not that that ever happened in England. Hahaha.

So much for dinner. No dessert in America. No dinner conversation in America. We're too busy.

I'm enjoying Dickens portrayal of American-British cultural differences, with America holding up the rear. Hey, it's (America) a very free country! Not just a free country, but a very free country. I think it's hilarious.

The spittoon. From Wikipedia:

"In the late 19th century, spittoons became a very common feature of pubs, brothels, saloons, hotels, stores, banks, railway carriages, and other places where people (especially adult men) gathered, most notably in the United States, but allegedly also in Australia."

WHAT HAPPENED TO TAPLEY?!?! Did he drown?

I'm enjoying MC but with a feeling that something is missing, and I think I've found it. Who is our hero? Who is the protagonist I can like? At the same time who is the antagonist I can truly hate?

I'm enjoying MC but with a feeling that something is missing, and I think I've found it. Who is our hero? Who is the protagonist I can like? At the same time who is the antagonist I can truly hate?Martin, at least up to this point in time, doesn't make it as a hero or as a likable protagonist. I feel like I'm having a smug, self-indulgent boy thrust upon me. Yet, in my mind, he's the only contender. Tapley is too jolly, while Tom's a good sidekick but not a hero, and Westlock is locked away in London somewhere.

At the same time, we can't despise Pecksniff or Old Martin like we enjoyed despising the likes of Fagin and Syke, or Wackford Squeers and Sir Mulberry Hawk, or Quilp and even grandfather, because they just aren't bad enough.

So, what gives? Is this a coming of age story of a full grown man?

Chapter 17

Chapter 17The subject matter discussed here is much more serious than in the previous chapter.

But there are still moments, like

-- He has too many aches and pains to reconcile with being alive.

-- I'm liking Tapley more. He is one of those people who accepts people as they are without prejudice.

-- Dickens is making quite a statement about slavery and how it warps American thinking. I can't speak to England, but his criticism would not have set well with most American I think.

-- With all the discussion about America not having an aristocracy or nobility, I wonder if Dickens read de Tocqueville? Tocqueville made a big deal about it.

-- Only 4 pounds 10 one way, England to America. Wow!

-- "Penetrate the mystery of his packing." Haha.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "I'm enjoying MC but with a feeling that something is missing, and I think I've found it. Who is our hero? Who is the protagonist I can like? At the same time who is the antagonist I can truly hate?..."

Xan

You ask a very important series of questions. In our last book titled Barnaby Rudge I did not see Barnaby as the hero or protagonist or even the most important or interesting character in the novel.

Now, with this novel, we have two Martin Chuzzlewit’s and neither seems to be nudging their way to the front of the line to be justifiably called the main protagonist, or antagonist or anything else yet either in a novel titled Martin Chuzzlewit. Well, perhaps soon?

I enjoy your comments of this week as they create a different spin on how we can approach the novel. In terms of your comments on slavery in America I wonder if Dickens’s comments in the novel can be better understood by suggesting the following. Dickens was a champion of the poor, the underclass and the impoverished in England. No doubt he saw similarities with the slaves in America. Also, England in the past decade had abolished the slave trade and slavery. I wonder if a bit of English superiority was at play in the novel.

As we progress through the novel there well might be shifts in our perceptions. It is always best to remember that this novel was written in parts over 19 months so Dickens may well tinker with what we know now with what we will end up knowing at the end of the novel.

Xan

You ask a very important series of questions. In our last book titled Barnaby Rudge I did not see Barnaby as the hero or protagonist or even the most important or interesting character in the novel.

Now, with this novel, we have two Martin Chuzzlewit’s and neither seems to be nudging their way to the front of the line to be justifiably called the main protagonist, or antagonist or anything else yet either in a novel titled Martin Chuzzlewit. Well, perhaps soon?

I enjoy your comments of this week as they create a different spin on how we can approach the novel. In terms of your comments on slavery in America I wonder if Dickens’s comments in the novel can be better understood by suggesting the following. Dickens was a champion of the poor, the underclass and the impoverished in England. No doubt he saw similarities with the slaves in America. Also, England in the past decade had abolished the slave trade and slavery. I wonder if a bit of English superiority was at play in the novel.

As we progress through the novel there well might be shifts in our perceptions. It is always best to remember that this novel was written in parts over 19 months so Dickens may well tinker with what we know now with what we will end up knowing at the end of the novel.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Only 4 pounds 10 one way, England to America. Wow!"

Yes, but don't forget: It's steerage, and you'll have to hide from people who don't know you anyway. At least, if you are Martin.

Yes, but don't forget: It's steerage, and you'll have to hide from people who don't know you anyway. At least, if you are Martin.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "I'm enjoying MC but with a feeling that something is missing, and I think I've found it. Who is our hero? Who is the protagonist I can like? At the same time who is the antagonist I can truly hate?..."

A good question: Who is the hero? I fear that Tom Pinch will not make a very credible hero, and I also doubt that John Westlock will come to the fore in the American chapters, and so we are stuck with Martin and Mark. The latter is really developing into more of a round character instead of an always-jolly Sancho Pansa: The more he knows about America, especially when it comes to slavery, the angrier he gets, but still he puts a good face on it, although I think in his pockets, the knuckles of his fists are white with tension. Will he lose his temper sooner or later, and get Martin into trouble?

As to Martin, he reminds me of those not-too-likeable main characters in Tobias Smollett's novels. Smollett, however, was not too nice a person himself, but rather grumpy, and so I have a feeling that he did not actually notice that Roderick Random and Peregrine Pickle were unpleasant fellows. Dickens, however, wants us to notice the faults in Martin's character, and I daresay he has something in mind with this unsatisfactory hero ...

A good question: Who is the hero? I fear that Tom Pinch will not make a very credible hero, and I also doubt that John Westlock will come to the fore in the American chapters, and so we are stuck with Martin and Mark. The latter is really developing into more of a round character instead of an always-jolly Sancho Pansa: The more he knows about America, especially when it comes to slavery, the angrier he gets, but still he puts a good face on it, although I think in his pockets, the knuckles of his fists are white with tension. Will he lose his temper sooner or later, and get Martin into trouble?

As to Martin, he reminds me of those not-too-likeable main characters in Tobias Smollett's novels. Smollett, however, was not too nice a person himself, but rather grumpy, and so I have a feeling that he did not actually notice that Roderick Random and Peregrine Pickle were unpleasant fellows. Dickens, however, wants us to notice the faults in Martin's character, and I daresay he has something in mind with this unsatisfactory hero ...

As to the villains: Pecksniff may be a buffoon, but as I once said, in his conversation with Mrs. Todgers - you remember, when he was flirting with her in his sodden drunkenness -, he showed a pretty dark and despicable side, and I wonder whether we will not see it return in one of the future chapters.

Apart from that, there are still Anthony and his son Jonas - they are skinflints and hardnosed businessness, and there is lots of bad dealings to be expected from them.

Apart from that, there are still Anthony and his son Jonas - they are skinflints and hardnosed businessness, and there is lots of bad dealings to be expected from them.

Jonas. Yes, Jonas. He has villain potential. He has it written all over him. I had forgotten about Jonas. Good catch, Tristram.

Jonas. Yes, Jonas. He has villain potential. He has it written all over him. I had forgotten about Jonas. Good catch, Tristram.

Emma wrote: "Truthfully, as a modern American who loves Dickens, these chapters were difficult to read. I don't mind someone critiquing America (I critique America too!), it just kinda stinks to feel like one o..."

Yes, Emma, I can understand how you might feel about these descriptions. I had the feeling that Dickens jammed all the bad experiences and impressions he had during his stay in the U.S. into those three chapters. In fact, these chapters are more like a series of sketches with the obvious intention of parading all these caricatures, and the actual plot seems to be as much forgotten as Mark Tapley was by Martin in the wake of his encounter with the newspaper man.

Mr. Bevan is probably some kind of alibi: By introducing him, Dickens can always defend himself against the reproach of complete America-bashing. Maybe, Dickens also saw that the rank and file of Americans were like Mr. Bevan but that people like Major Pawkins, Colonel Diver and so on had somehow managed to move themselves into the foreground and take the helm of the American ship. There is a dialogue to this effect in Chapter 17, unless I'm much mistaken.

Yes, Emma, I can understand how you might feel about these descriptions. I had the feeling that Dickens jammed all the bad experiences and impressions he had during his stay in the U.S. into those three chapters. In fact, these chapters are more like a series of sketches with the obvious intention of parading all these caricatures, and the actual plot seems to be as much forgotten as Mark Tapley was by Martin in the wake of his encounter with the newspaper man.

Mr. Bevan is probably some kind of alibi: By introducing him, Dickens can always defend himself against the reproach of complete America-bashing. Maybe, Dickens also saw that the rank and file of Americans were like Mr. Bevan but that people like Major Pawkins, Colonel Diver and so on had somehow managed to move themselves into the foreground and take the helm of the American ship. There is a dialogue to this effect in Chapter 17, unless I'm much mistaken.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Jonas. Yes, Jonas. He has villain potential. He has it written all over him. I had forgotten about Jonas. Good catch, Tristram."

I'd rather not catch a Jonas right now, Xan, since I've already caught a cold ;-)

I'd rather not catch a Jonas right now, Xan, since I've already caught a cold ;-)

Yes, I think Jonas will make a good villain indeed. Although I still think Pecksniff is more villainous than he seems now, because he's funny as well.

And I hope along that either Martin or Mark will prove to be a real protagonist - or someone else ... I miss that too.

And I hope along that either Martin or Mark will prove to be a real protagonist - or someone else ... I miss that too.

Pecksinff probably is, Jantine. Tristram made a good point when he said Pecksniff has bamboozled other characters, but the reader sees him for the bumbler he is. He's a poor excuse for a Ralph Nickleby, but perhaps, as you say, that will change -- if he doesn't crack his head open on the floor first.

Pecksinff probably is, Jantine. Tristram made a good point when he said Pecksniff has bamboozled other characters, but the reader sees him for the bumbler he is. He's a poor excuse for a Ralph Nickleby, but perhaps, as you say, that will change -- if he doesn't crack his head open on the floor first.

Tristram wrote: "" In fact, these chapters are more like a series of sketches with the obvious intention of parading all these caricatures, and the actual plot seems to be as much forgotten as...."

Tristram wrote: "" In fact, these chapters are more like a series of sketches with the obvious intention of parading all these caricatures, and the actual plot seems to be as much forgotten as...."Absolutely! It definitely has the feel of a series of sketches. Especially the pace everything is described at? Large issues like slavery, social hypocrisy, and poverty could each have their own dedicated chapter, instead of appearing in one chapter all at once!

Mr. Jefferson Brick Proposes an Appropriate Sentiment

Chapter 16

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"My War Correspondent, sir — Mr Jefferson Brick!"

Martin could not help starting at this unexpected announcement, and the consciousness of the irretrievable mistake he had nearly made.

Mr. Brick seemed pleased with the sensation he produced upon the stranger, and shook hands with him, with an air of patronage designed to reassure him, and to let him blow that there was no occasion to be frightened, for he (Brick) wouldn't hurt him.

"You have heard of Jefferson Brick, I see, sir," quoth the colonel, with a smile. "England has heard of Jefferson Brick. Europe has heard of Jefferson Brick. Let me see. When did you leave England, sir?"

"Five weeks ago," said Martin.

"Five weeks ago," repeated the colonel, thoughtfully; as he took his seat upon the table, and swung his legs. "Now let me ask you, sir which of Mr Brick's articles had become at that time the most obnoxious to the British Parliament and the Court of Saint James's?"

"Upon my word," said Martin, "I —"

"I have reason to know, sir," interrupted the colonel, "that the aristocratic circles of your country quail before the name of Jefferson Brick. I should like to be informed, sir, from your lips, which of his sentiments has struck the deadliest blow —"

"At the hundred heads of the Hydra of Corruption now grovelling in the dust beneath the lance of Reason, and spouting up to the universal arch above us, its sanguinary gore," said Mr Brick, putting on a little blue cloth cap with a glazed front, and quoting his last article.

"The libation of freedom, Brick" — hinted the colonel.

" — Must sometimes be quaffed in blood, colonel," cried Brick. And when he said "blood," he gave the great pair of scissors a sharp snap, as if they said blood too, and were quite of his opinion.

Commentary: American Yellow Journalism:

In the first of he American scenes, Phiz offers a number of visual details as tacit commentary upon the principals in the scene, the offices of the New York Rowdy Journal: bottles of ink and poison (presumably used by the editorial staff in equal portions), a slang dictionary, and a poster advertising "disclosures," presumably about the private lives of public figures, a tendency which in the letterpress Martin pronounces horribly "personal." Jefferson Brick's shears imply that, in the United States, the print media facilitate partisan and personal attacks, some of which can fate-like severe a political career. Young Martin, looking much as thirty-year-old author Charles Dickens must have looked at the time of his first American tour (i.e., 5 February through 7 June 1842), has discovered a society riven by political factions, but united by the common goal of making as much money as possible, by fair means or foul. Attacked by the popular press such as Brother Jonathan for speaking out against rampant American expropriation of European authors' works, Dickens had felt both vilified and exploited, for just as American publishers had ruthlessly mined the Waverley Novels of Sir Walter Scott, now they were freely pilfering the works of Frederick Marryat and Dickens himself.

The sprawling, large-scale signature in a cloud of squiggles hovers above the recumbent figure, as if to identify Mark with the newspaper's "rowdiness." The "rowdy" nature of the office is reflected in the clippings strewn about the floor, and the "rowdy" nature of Diver and Brick by their choosing to sit on the large (and highly realistic) editor's that dominates the room rather than, like the more civilized Martin, upon a chair. With bemused interest Martin reads the paper as a whole, Brick cuts it to pieces. Whereas Phiz has made young Martin a realistic figure, he has mercilessly caricatured Jefferson Brick (centre) and Colonel Diver (left) as they sip the champagne that the unscrupulous editor has just extorted from the captain of the transAtlantic vessel The Screw in New York harbour.

This expose of American journalism is the first of the illustrations depicting Dickens's own direct impressions of America. Attacked by the popular press for speaking out about American publishers' massive violations of British copyright and their flagrant piracies of the works of popular British authors, Dickens takes artistic revenge by characterizing all transAtlantic journals as "rowdy," vituperative, and scurrilous. Dickens's heavy-handed satire of Americans in general and of journalists in particular unleashed a largely negative debate about Dickens's ingratitude: actor-manager William Macready and writer Harriet Martineau sympathized with the Americans and against Dickens; Thomas Carlyle, on the other hand, relished Dickens's assault on Yankle doodledom as "capital." The moment that Phiz, undoubtedly assisted by Dickens in terms of American costume, has realized is this:

"I will give you," he said to Colonel Diver and Martin, "'The Rowdy Journal and its brethren; the well of Truth, whose waters are black from being composed of printers' ink" (Ch. 16).

Diver's pomposity and high-flown rhetoric (to say nothing of his egotism and hypocrisy) immediately recall the comic excesses of Seth Pecksniff.

"It is in such enlightened means," said a voice, almost in Martin's ear, "That the bubbling passions of my country find a vent."

Chapter 16

Fred Barnard

Commentary:

The letterpress's image of "bubbling passions finding vent" is not especially menacing, however, in that it suggests a water geyser such as Old Faithful in Yellowstone National Park rather than an active volcano such as Mount Vesuvius in Italy. No wonder that young Dickens, fresh from his 1842 reading tour of the United States, associates the "rowdy" journalist with a frothy, bubbly beverage — champagne, of which he has extorted a number of bottles from the captain of "The Screw."

Fred Barnard's first American illustration (discounting the scene of Mark Tapley's comforting his fellow immigrants in steerage) depicts in a close up the arrival of "The Screw" (propeller-driven vessel) in New York harbour in Chapter 16, although the printer has incorrectly placed it in the preceding chapter, when Martin and Mark are still in the middle of the five-week passage. In the letterpress, like diminutive pirates bent upon plunder, a legion of news-boys boards and overruns the packet steamer, hawking wares whose quality and character Dickens makes immediately evident in their titles: the New York Sewer, Stabber, Family Spy, Private Listener, Peeper, Plunderer, Keyhole Reporter, and Rowdy Journal, a scurrilous catalogue that implies the presence of at least eight vendors. However, instead of a milling crowd of miniature entrepreneurs and shipboard customers set against a panorama of docks and ships in America's busiest port, Barnard shows a lone news-boy with a bundle of New York Sewers tucked under his arm. This, indeed, is the very paper to which Dickens in metonymy devotes more than half-a-column: they are all much the same in their partisan prose, accounts of violent incidents, and personal attacks. Barnard sketchily suggests a crowded quay in the background, focusing on Colonel Diver, editor of the Rowdy Journal, in the foreground, centre; he and the newsboy to the right embody the American fifth estate which Dickens vilifies.

Martin has yet to turn and confront the owner of the disembodied voice speaking in his ear, so that we cannot evaluate by his facial expression Martin's immediate reaction as his back is towards us and his face to the shore. Thus, Barnard compels us to read the illustration by reading the letterpress. As Martin turns, he sees what we read: "a sallow gentleman, with sunken cheeks, black hair, small twinkling eyes, and a singular expression . . . which was not a frown, nor a leer, and yet might have been mistaken at first glance for either." Through the narrator's description we can assume that Martin is struck by Diver's "vulgar cunning and conceit." Although these qualities of Diver's physiognomy are not easily realized in illustration, Barnard has given us a tall, lean American nattily rather than "shabbily" dress. He is neither the gangly cartoon figure of Phiz's "Mr. Jefferson Brick Proposes an Appropriate Sentiment" (July 1843), nor the ugly and disreputable American newspaper editor of Dickens's letterpress. To give Diver's words a theatrical referent Barnard has him gesture with his left arm to the news-boy selling The Sewer.

Although his arms are therefore not impressively folded as in Dickens's initial description of him, Colonel Diver's surtout does extend to his ankles, and he does sport a buff waistcoat frilled shirt. He casually leans full length against the bulwark of the vessel, and carries exactly the sort of cane Dickens mentions: "shod with a mighty ferule at one end and armed with a great metal knob at the other, [it] depended from a line-and-tassel on his wrist." However, Barnard has markedly reduced the size of the knob, and therefore rendered Colonel Diver far less menacing, as may be more appropriate to the spirit of Anglo-American co-operation after the Civil War.

Colonel Diver and Jefferson Brick

Chapter 16

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

Commentary:

In this fifth full-page dual character study for the novel, Eytinge examines the American fifth estate's representatives in a manner far more benign than that of Dickens and Phiz in the serial illustration set in the offices of The New York Rowdy Journal (a pseudonym for the notorious The New York Evening Tattler, which made an attempt on 11 August 1842 to embarrass Dickens with a letter entitled "Boz's Opinion of Us," about copyright — spuriously published as if by Charles Dickens himself).

Sol Eytinge, unlike Fred Barnard in the Household Edition of the novel, the second volume in the Chapman and Hall series, introduces the newspaper-editing Colonel in his business office, rather than on the deck of "The Screw," the steam-driven vessel on which young Martin and Mark Tapley have crossed the Atlantic. Barnard was interested in the moment in which the newsboys came aboard to flog such elevating reading as The New York Sewer. At this point Dickens introduces the disembodied voice of Colonel Diver at Martin's ear:

"It is in such enlightened means," said a voice almost in Martin's ear, "that the bubbling passions of my country find a vent."

Martin turned involuntarily, and saw, standing close at his side, a sallow gentleman, with sunken cheeks, black hair, small twinkling eyes, and a singular expression hovering about that region of his face, which was not a frown, nor a leer, and yet might have been mistaken at the first glance for either. Indeed it would have been difficult, on a much closer acquaintance, to describe it in any more satisfactory terms than as a mixed expression of vulgar cunning and conceit. This gentleman wore a rather broad–brimmed hat for the greater wisdom of his appearance; and had his arms folded for the greater impressiveness of his attitude. He was somewhat shabbily dressed in a blue surtout reaching nearly to his ankles, short loose trousers of the same colour, and a faded buff waistcoat, through which a discoloured shirt-frill struggled to force itself into notice, as asserting an equality of civil rights with the other portions of his dress, and maintaining a declaration of Independence on its own account. His feet, which were of unusually large proportions, were leisurely crossed before him as he half leaned against, half sat upon, the steamboat's bulwark; and his thick cane, shod with a mighty ferule at one end and armed with a great metal knob at the other, depended from a line-and-tassel on his wrist. Thus attired, and thus composed into an aspect of great profundity, the gentleman twitched up the right-hand corner of his mouth and his right eye simultaneously, and said, once more, —

"It is in such enlightened means that the bubbling passions of my country find a vent."

As he looked at Martin, and nobody else was by, Martin inclined his head, and said, —

"You allude to —?"

"To the Palladium of rational Liberty at home, sir, and the dread of Foreign oppression abroad," returned the gentleman, as he pointed with his cane to an uncommonly dirty newsboy with one eye. "To the Envy of the world, sir, and the leaders of Human Civilization.

Thus, Fred Barnard in 1872 chose a scene with a dramatic backdrop, New York harbour, for the scene in which Martin first encounters America, "'It is in such enlightened means,' said a voice, almost in Martin's ear, 'That the bubbling passions of my country find a vent'", a woodcut that emphasizes the Colonel (left of centre) and a newsboy (right on centre). Although Barnard does not depict the Colonel as a grotesque in the manner of Phiz in "Mr. Jefferson Brick Proposes an Appropriate Sentiment" (July 1843), neither does he describe a wholly admirable newsman. Eytinge, on the other hand, offers a pair of journalists who are not merely realistic rather thab caricatured, but are drinking champagne in the middle of the day, booty extorted from the Captain of "The Screw," in fact, whereas Phiz's Martin seems a perfectly respectable young man of middle-class mould in the height of English fashion — a figure presumably based on thirty-year-old Charles Dickens himself. The moment that Phiz realised some thirty-four years before Eytinge is essentially the same, but Eytinge omits much of the detail (as well as Martin) in order to focus the reader's attention on the two representatives of the fifth estate:

Presently they turned up a narrow street, and presently into other narrow streets, until at last they stopped before a house whereon was painted in great characters, "ROWDY JOURNAL."

The colonel, who had walked the whole way with one hand in his breast, his head occasionally wagging from side to side, and his hat thrown back upon his ears, like a man who was oppressed to inconvenience by a sense of his own greatness, led the way up a dark and dirty flight of stairs into a room of similar character, all littered and bestrewn with odds and ends of newspapers and other crumpled fragments, both in proof and manuscript. Behind a mangy old writing-table in this apartment sat a figure with a stump of a pen in its mouth and a great pair of scissors in its right hand, clipping and slicing at a file of Rowdy Journals; and it was such a laughable figure that Martin had some difficulty in preserving his gravity, though conscious of the close observation of Colonel Diver.

The individual who sat clipping and slicing as aforesaid at the Rowdy Journals, was a small young gentleman of very juvenile appearance, and unwholesomely pale in the face; partly, perhaps, from intense thought, but partly, there is no doubt, from the excessive use of tobacco, which he was at that moment chewing vigorously. He wore his shirt-collar turned down over a black ribbon; and his lank hair — a fragile crop — was not only smoothed and parted back from his brow, that none of the Poetry of his aspect might be lost, but had, here and there, been grubbed up by the roots; which accounted for his loftiest developments being somewhat pimply. He had that order of nose on which the envy of mankind has bestowed the appellation "snub," and it was very much turned up at the end, as with a lofty scorn. Upon the upper lip of this young gentleman were tokens of a sandy down; so very, very smooth and scant, that, though encouraged to the utmost, it looked more like a recent trace of gingerbread than the fair promise of a moustache; and this conjecture, his apparently tender age went far to strengthen. He was intent upon his work. Every time he snapped the great pair of scissors, he made a corresponding motion with his jaws, which gave him a very terrible appearance.

Martin was not long in determining within himself that this must be Colonel Diver's son; the hope of the family, and future mainspring of the Rowdy Journal. Indeed he had begun to say that he presumed this was the colonel's little boy, and that it was very pleasant to see him playing at Editor in all the guilelessness of childhood, when the colonel proudly interposed and said, —

"My War Correspondent, sir, — Mr. Jefferson Brick!"

Eytinge has made Brick smaller than Diver, but has not given him the straggling moustache of Phiz's character, and the newspaper office in this 1867 woodcut is in nothing like the disarray of its 1843 counterpart, so that the overall effect of the Diamond Edition's illustration is hardly satirical, but rather realistic portraiture, with a dignified and wholly serious Colonel presiding over the scene.

"The Rowdy Journal"Office.

Chapter 16

Harry Furniss

1910

Text Illustrated:

Presently they turned up a narrow street, and presently into other narrow streets, until at last they stopped before a house whereon was painted in great characters, "ROWDY JOURNAL."

The colonel, who had walked the whole way with one hand in his breast, his head occasionally wagging from side to side, and his hat thrown back upon his ears— like aman who was oppressed to inconvenience by a sense of his own greatness— led the way up adark and dirty flight of stairs into a room of similar character, all littered and bestrewn withodds and ends of newspapers and other crumpled fragments, both in proof and manuscript.Behind a mangy old writing-table in this apartment sat a figure with a stump of a pen in itsmouth and a great pair of scissors in its right hand, clipping and slicing at a file of RowdyJournals; and it was such a laughable figure that Martin had some difficulty in preserving hisgravity, though conscious of the close observation of Colonel Diver.

The individual who sat clipping and slicing as aforesaid at the Rowdy Journals, was a small young gentleman of very juvenile appearance, and unwholesomely pale in the face; partly, perhaps, from intense thought, but partly, there is no doubt, from the excessive use of tobacco, which he was at that moment chewing vigorously. He wore his shirt-collar turned down over a black ribbon; and his lank hair— a fragile crop — was notonly smoothed and parted back from his brow, that none of the Poetry of his aspect mightbe lost, but had, here and there, been grubbed up by the roots: which accounted for hisloftiest developments being somewhat pimply. He had that order of nose on which theenvy of mankind has bestowed the appellation"snub," and it was very much turned up atthe end, as with a lofty scorn. Upon the upper lip of this young gentleman were tokens ofa sandy down—so very, very smooth and scant, that, though encouraged to the utmost, itlooked more like a recent trace of gingerbread than the fair promise of a moustache; andthis conjecture his apparently tender age went far to strengthen. He was intent upon hiswork. Every time he snapped the great pair of scissors, he made a corresponding motionwith his jaws, which gave him a very terrible appearance.

Commentary: American Freedom of the Press at "The Rowdy Journal":

Arrived in America, Martin becomes Dickens's stalking-horse in exposing the scurrilous journalistic practices of the New York newspapers, Dickens's grievance being how his views on international copyright were being reported in Brother Jonathan. The "yellow journalism" of Colonel Diver's Rowdy Journal is exemplified by the inflated pro-Yankee and anti-British rhetoric of the bellicose Mr. Jefferson Brick, the paper's juvenile "war correspondent" (shown clipping columns of print at his "mangy" desk, left).

Martin and Mark visit these same office of the Fifth Estate to join the newspapermen in a glass of champagne which the Colonel has extorted from the captain of the packet-ship, infested with newsboys for the various "scandal rags" in the Fred Barnard Household Edition illustration "It is in such enlightened means," said a voice, almost in Martin's ear, "That the bubbling passions of my country find a vent", although Barnard assailed the scene in the newspaper office which Dickens's original illustrator, Hablot Knight Browne, had described in the July 1843 steel-engraving Mr. Jefferson Brick Proposes an Appropriate Sentiment (Chapter 16). In the Household Edition, however, Fred Barnard realizes the scene long after the champagne-imbibing when, waiting in the corridor for dinner at Mrs. Pawkins' rooming-house, Martin expresses appreciation of the honest observations of a Pawkins' waiter, in "You're the pleasantest fellow I have seen yet," said Martin, clapping him on the back, "And give me a better appetite than bitters" — recalling Mark's enjoying the company of a former slave, Cicero, in the corridor outside the journal's offices. In the original serial, it is not Martin but the honest, pro-abolitionist Mark Tapley who interacts with a genial Black employee, in Mr. Tapley succeeds in finding a jolly subject for contemplation (the companion illustration for July 1843). Perhaps the difference may be accounted for by the different era in which the artists were working, for Dickens encountered many Americans in the first reading trip (1842) who upheld slavery as an economic and social institution, whereas Fred Barnard composed his narrative-pictorial sequence not long after the Union victory in the American Civil War and President Lincoln's signing the Emancipation Proclamation. Harry Furniss, on the other hand, was half-a-century and more removed from Dickens's concerns with yellow journalism, America's refusal to subscribe to international copyright, and the evils of slavery; hence, these controversies raised in this novel and American Notes (1842) and long forgotten by the English reading public, Harry Furniss devotes just a single illustration to this initial phase of Martin's American adventures.

Furniss's version of the precocious boy-journalistic and his jingoistic editor is markedly more realistic and less cartoon-like than Phiz's, the 1910 figures derived more probably from Barnard's illustrations. Furniss has given the Colonel a more respectable suit than the text and Phiz supply:

Martin turned involuntarily, and saw, standing close at his side, a sallow gentleman, with sunken cheeks, black hair, small twinkling eyes, and a singular expression hovering about that region of his face, which was not a frown, nor a leer, and yet might have been mistaken at the first glance for either. Indeed it would have been difficult, on a much closer acquaintance, to describe it in any more satisfactory terms than as a mixed expression of vulgar cunning and conceit. This gentleman wore a rather broad-brimmed hat for the greater wisdom of his appearance; and had his arms folded for the greater impressiveness of his attitude. He was somewhat shabbily dressed in a blue surtout reaching nearly to his ankles, short loose trousers of the same colour, and a faded buff waistcoat, through which a discoloured shirt-frill struggled to force itself into notice, as asserting an equality of civil rights with the other portions of his dress, and maintaining a declaration of Independence on its own account. His feet, which were of unusually large proportions, were leisurely crossed before him as he half leaned against, half sat upon, the steamboat's bulwark; and his thick cane, shod with a mighty ferule at one end and armed with a great metal knob at the other, depended from a line-and-tassel on his wrist.

Although Furniss has conveyed the Colonel's facial expression effectively, his clothing does not appear to be as "shabby" and disreputable as Dickens stipulates, his feet are no larger than Martin's, and the cane is not evident here. Although Barnard does no better with Colonel Diver's suit, his portrait includes both the formidable cane and the sunken cheeks, and is therefore an improvement on both Furniss's newspaperman and Phiz's cartoon-figure, although clearly the Barnard character in the light waistcoat and broad-brimmed hat is derived from the original July 1843 steel-engraving. Whereas Phiz has Jefferson Brick wearing a cap, that same cap is sitting on top of a candle (left) in Furniss's generalised description of the "Rowdy Journal Editorial Office" as the door, upper right, announces for the room in a building on New York's Great White Way. Martin, for his part, seems bemused in the Furniss illustration at the notion that this snub-nosed, gangly boy playing with scissors and "office paste" is a "war correspondent," let alone that the Court of St. James should be accustomed to quake at the brilliance of his anti-British editorials — at least, Furniss is accurate in his depiction of the nose, if not of the employer of the owner of the nose.

Readers even in the United States have long forgotten Benjamin Day's weekly newspaper Brother Jonathan(1842), which focused on reprinting English fiction without paying royalties to such authors as Sir Walter Scott, Sir Edward G. D. Bulwer-Lytton, but they have the reverent, Dickens's satire on American journalism in the first of the "American Chapters" of Martin Chuzzlewit,as exemplified by Colonel Diver, editor of the New York Rowdy Journal and jingoistic "War Correspondent," Jefferson Brick.

"You're the pleasantest fellow I have seen yet"

Chapter 16

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

They were walking back very leisurely; Martin arm-in-arm with Mr. Jefferson Brick, and the major and the colonel side-by-side before them; when, as they came within a house or two of the major's residence, they heard a bell ringing violently. The instant this sound struck upon their ears, the colonel and the major darted off, dashed up the steps and in at the street-door (which stood ajar) like lunatics; while Mr. Jefferson Brick, detaching his arm from Martin's, made a precipitate dive in the same direction, and vanished also.

"Good Heaven!" thought Martin. "The premises are on fire! It was an alarm bell!"

But there was no smoke to be seen, nor any flame, nor was there any smell of fire. As Martin faltered on the pavement, three more gentlemen, with horror and agitation depicted in their faces, came plunging wildly round the street corner; jostled each other on the steps; struggled for an instant; and rushed into the house, a confused heap of arms and legs. Unable to bear it any longer, Martin followed. Even in his rapid progress he was run down, thrust aside, and passed, by two more gentlemen, stark mad, as it appeared, with fierce excitement.

"Where is it?" cried Martin, breathlessly, to a negro whom he encountered in the passage.

"In a eatin room, sa. Kernell, sa, him kep a seat 'side himself, sa."

"A seat!" cried Martin.

"For a dinnar, sa."

Martin started at him for a moment, and burst into a hearty laugh; to which the negro, out of his natural good humour and desire to please, so heartily responded, that his teeth shone like a gleam of light. 'You're the pleasantest fellow I have seen yet," said Martin clapping him on the back, "and give me a better appetite than bitters."

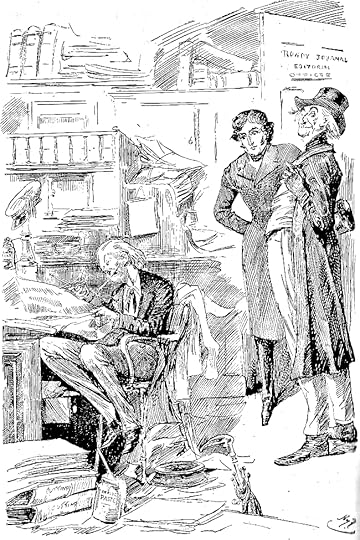

Mr. Tapley succeeds in finding a jolly subject for contemplation

Chapter 17

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

Mr. Tapley appeared to be taking his ease on the landing of the first floor; for sounds as of some gentleman established in that region whistling Rule Britannia with all his might and main, greeted their ears before they reached the house. On ascending to the spot from whence this music proceeded, they found him recumbent in the midst of a fortification of luggage, apparently performing his national anthem for the gratification of a grey-haired black man, who sat on one of the outworks (a portmanteau), staring intently at Mark, while Mark, with his head reclining on his hand, returned the compliment in a thoughtful manner, and whistled all the time. He seemed to have recently dined, for his knife, a casebottle, and certain broken meats in a handkerchief, lay near at hand. He had employed a portion of his leisure in the decoration of the Rowdy Journal door, whereon his own initials now appeared in letters nearly half a foot long, together with the day of the month in smaller type; the whole surrounded by an ornamental border, and looking very fresh and bold.

Commentary: Addendum to "American Notes for General Circulation":

The picture of Mark Tapley, the door of the New York Rowdy Journal, and the liberated slave Cicero complements the first plate for monthly instalment seven, which shows the journal's "war correspondent," Jefferson Brick (centre), the journal's editor, Colonel Diver (left), and their 'European' guest, Martin (right). True to his Christian name, Mr. Tapley has made his "mark" upon the scandal-sheet's portal, having emblazoned not merely his initials (as in the letterpress) but his full name in ornate calligraphy, as if the office has now become his. The moment that Phiz has realized is this:

Having decorated the "Rowdy Journal" door with his own initials, he was whistling "Rule Britannia" for the gratification of a black man who stared intently at him.

Dickens and Phiz probably anticipated that readers of the July 1843 instalment would compare the pair of engravings that would have preceded the seventh number itself. By focussing on the former slave, Cicero, the writer and illustrator draw readers' attentions to the great flaw in the much-vaunted myth of American republican virtue. The picture of the jolly Englishman of proletarian origins, the door of the New York Rowdy Journal, and the liberated slave complements the first July 1843 illustration, which also involves an Englishman scrutinizing an American institution, namely free speech and the Fifth Estate, in the persons of the newspaper editor, Colonel Diver and his juvenile War Correspondent, Jefferson Brick. True to his Christian name, Mr. Tapley has made his "mark" upon the scandal-sheet's portal, having emblazoned not merely his initials (as in the letterpress) but his full name in ornate calligraphy, as if the office has now become his.

Phiz has diverged from the letterpress in having Mark carve his full name rather than merely his initials upon the door of the newspaper, but then Dickens may not have specified this detail in his earlier instructions and Phiz may have elected not to change his design when he read the chapter in proof. As it stands, however, the illustration challenges the authority of the letterpress, the ornate signature asserting a kind of disrespectful "Mark Tapley was here" assertion. The sprawling, large-scale signature in a cloud of squiggles hovers above the recumbent figure, as if to identify Mark with the newspaper's "rowdiness."

"Am I Not A Man and A Brother?" (Abolitionist Poster: 1787 & 1837):

The allusion may well be to an abolitionist poster then current in the northern American states; however, When Mark Tapley refers to Cicero as a "brother," he is probably alluding to one of the numerous anti-slavery medallions which Josiah Wedgewood issued from 1787 as his contribution to the abolitionist movement of Thomas Clarkson. One of the American recipients, Benjamin Franklin, may have translated the image of a kneeling African slave in chains to the celebrated poster produced in 1837 to incite American anti-slavery sentiment. Since Martin and Mark have just that morning landed in New York, it is unlikely that either of the young Englishmen has encountered the poster, however, so that Mark must be alluding to the motto on the Wedgewood medallion, "Am I not a man and a brother?" produced at his Staffordshire pottery works from a design by sculptor Henry Webber. Its appeal to both the reason and the sentiment of the late eighteenth century led to its becoming the basis for abolitionist posters distributed in British coffee houses, taverns, inns, reading societies, reading rooms, and assembly rooms — the various kinds of places in which Mark has apparently seen the iconic image:

"I mean that he's been one of them as there's picters of in the shops. A man and a brother, you know, sir," said Mr. Tapley, favouring his master with a significant indication of the figure so often represented in tracts and cheap prints." [Chapter XVII]

In this passage from Martin Chuzzlewit Dickens may well be making use of a poster that then had currency on both sides of the Atlantic:

The large, bold woodcut image of a supplicant male slave in chains appears on the 1837 broadside publication of John Greenleaf Whittier's antislavery poem, "Our Countrymen in Chains." The design was originally adopted as the seal of the Society for the Abolition of Slavery in England in the 1780s, and appeared on several medallions for the society made by Josiah Wedgwood as early as 1787. Here, in addition to Whittier's poem, the appeal to conscience against slavery continues with two further quotes. The first is the scriptural warning, "He that stealeth a man and selleth him, or if he be found in his hand, he shall surely be put to death. "Exod[us] XXI, 16." Next the claim, "England has 800,000 Slaves, and she has made them free. America has 2,250,000! and she holds them fast!!!!" The broadside is advertised at "Price Two Cents Single; or $1.00 per hundred. [Originally published by the New York office of the Anti-Slavery Society — "Am I not a man and a brother?" in the Library of Congress]

The illustrations reminds readers of the twenty-first century that slavery, although outlawed in the British Empire in 1832, continued to flourish in the American South until President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation in the midst of the American Civil War twenty years later, stipulating that "that all persons held as slaves" within the rebellious states "are, and henceforward shall be free." We should view the reception of the Phiz illustration in Great Britain and America in 1843, however, in the context of the U. S. Supreme Court's ruling that the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793 was perfectly constitutional. In reaction, three Northern and anti-slavery States (New York, Vermont, and Ohio) had challenged the validity of the ruling by passing personal liberty laws which recognized former slaves as citizens, even as the Georgia legislature affirmed that it would never recognize Blacks as citizens. Therefore, in depicting Cicero in a positive light Dickens and Phiz were casting their lot with the Abolitionists as to whether the American Negro should enjoy life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, or whether he or she was merely some White American's personal property. For the next eight years, however, undoubtedly mindful of the firestorm of controversy that Martin Chuzzlewit and American Notes for General Circulation had caused on both sides of the Atlantic, Dickens published nothing further about the failed "Republic of his Imagination." However, in his new journal begun in 1850, Household Words he ran a number of articles about his personal horror of American slavery, including "Frauds on the Fairies" (1 October 1853) and "North American Slavery" (18 September 1852).

"Jiniral Fladdock!"

Chapter 17

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

Martin felt his reason going: and as a means of saving himself, besought the other sister (seeing a piano in the room) to sing. With this request she willingly complied; and a bravura concert, solely sustained by the Misses Noriss, presently began. They sang in all languages — except their own. German, French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Swiss; but nothing native; nothing so low as native. For, in this respect, languages are like many other travellers; ordinary and commonplace enough at home, but specially genteel abroad.

There is little doubt that in course of time the Misses Norris would have come to Hebrew, if they had not been interrupted by an announcement from the Irishman, who flinging open the door, cried in a loud voice:

"Jiniral Fladdock!"

"My!"cried the sisters, desisting suddenly. "The general come back!"

As they made the exclamation, the general, attired in full uniform for a ball, came darting in with such precipitancy that, hitching his boot in the carpet, and getting his sword between his legs, he came down headlong, and presented a curious little bald place on the crown of his head to the eyes of the astonished company. Nor was this the worst of it: for being rather corpulent and very tight, the general being down, could not get up again, but lay there writing and doing such things with his boots, as there is no other instance of in military history.

Of course there was an immediate rush to his assistance; and the general was promptly raised. But his uniform was so fearfully and wonderfully made, that he came up stiff and without a bend in him like a dead clown, and had no command whatever of himself until he was put quite flat upon the soles of his feet, when he became animated as by a miracle, and moving edgewise that he might go in a narrower compass and be in less danger of fraying the gold lace on his epaulettes by brushing them against anything, advanced with a smiling visage to salute the lady of the house.

Commentary:

The text juxtaposes the Humpty-Dumpty figure of the operetta general, Fladdock, with the Americans of no title or rank, both pro-abolitionists, the snobbish Mr. Norris and the genuine Mr. Bevan, both of whom are critical of their society and appraise it with the cool skepticism of Martin Chuzzlewit, the outsider and observer of American morals and mores. Although Barnard foregrounds the awkward military man, he includes the fashionably dressed Miss Norrisses, singing at the upright piano, and, beside them, the ever-observant Martin.

I like the richness and detail in Bernard's illustrations of these characters in this book. Excellent work, I think.

I like the richness and detail in Bernard's illustrations of these characters in this book. Excellent work, I think.Thx, Kim.

Kim wrote: "

"The Rowdy Journal"Office.

Chapter 16

Harry Furniss

1910

Text Illustrated:

Presently they turned up a narrow street, and presently into other narrow streets, until at last they stopped befo..."

Kim. As always, the addition of the illustrations makes our week’s reading complete.

This Furniss illustration is very interesting. I enjoy the depiction of both the characters and their surroundings. To me, it captures the emotion of the letterpress very well.

"The Rowdy Journal"Office.

Chapter 16

Harry Furniss

1910

Text Illustrated:

Presently they turned up a narrow street, and presently into other narrow streets, until at last they stopped befo..."

Kim. As always, the addition of the illustrations makes our week’s reading complete.

This Furniss illustration is very interesting. I enjoy the depiction of both the characters and their surroundings. To me, it captures the emotion of the letterpress very well.

Kim wrote: "

Mr. Tapley succeeds in finding a jolly subject for contemplation

Chapter 17

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

Mr. Tapley appeared to be taking his ease on the landing of the first floor; for sounds as o..."

Well, this illustration is a Phiz, so what’s not to like? In this case, I find it powerful because of its simplicity. Often Phiz’s illustrations are either packed with people or detail - and sometimes both. In this illustration, there is a stark simplicity.

Consider the contrast in the aspect of the men’s clothes, their body language and facial expressions. On the left side of the plate we see Cicero. He is poorly dressed, sitting on a wooden crate, shoeless, and leaning forward with a slight look of what ... surprise, awe, confusion? On the right side of the plate we have Mark Tapley. He is in a position of repose, he is dressed well, and has good leather boots on his feet. Two men from different worlds meeting.

Mr. Tapley succeeds in finding a jolly subject for contemplation

Chapter 17

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

Mr. Tapley appeared to be taking his ease on the landing of the first floor; for sounds as o..."

Well, this illustration is a Phiz, so what’s not to like? In this case, I find it powerful because of its simplicity. Often Phiz’s illustrations are either packed with people or detail - and sometimes both. In this illustration, there is a stark simplicity.

Consider the contrast in the aspect of the men’s clothes, their body language and facial expressions. On the left side of the plate we see Cicero. He is poorly dressed, sitting on a wooden crate, shoeless, and leaning forward with a slight look of what ... surprise, awe, confusion? On the right side of the plate we have Mark Tapley. He is in a position of repose, he is dressed well, and has good leather boots on his feet. Two men from different worlds meeting.

As to the "hero" of the piece, my Dickens set always contains a list of characters with notations regarding each character. This set (the Oxford Illustrated Dickens) does list one character as the hero of the story, so if you want to search for the list it is there for all to see. I will not mention it in case you would consider that a spoiler or want to come to your own conclusion as the story progresses.

As to the "hero" of the piece, my Dickens set always contains a list of characters with notations regarding each character. This set (the Oxford Illustrated Dickens) does list one character as the hero of the story, so if you want to search for the list it is there for all to see. I will not mention it in case you would consider that a spoiler or want to come to your own conclusion as the story progresses. Thanks Kim for the illustrations. I always enjoy the additional ones to go with those in my books.

I wonder if the America of that time period was really as described by Dickens or as observed by him during his travels here. I certainly hope not, but I am sure there certainly were people like the ones described. We do have a vast variety of characters now and I am sure back then as well.

Bobbie,

Bobbie,Thank you for your consideration. Spoilers don't bother me except maybe when someone tells me who did it in a whodunit. But I'll wait. Plus I think the book title might have something to say about it. I shall see.

I think Dickens was disappointed in America. I know that's not an original observation: he says as much. But it colors these chapters to know that. There's some bitterness in this part that's unusual for Dickens in my (incomplete) experience. Unremitting, leaden. Sad.