The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Martin Chuzzlewit

Martin Chuzzlewit

>

MC, Chp. 06-08

Chapter 7

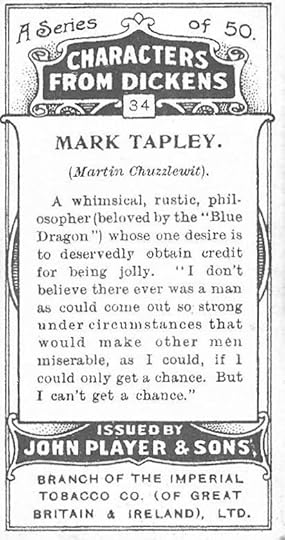

Here we get another glimpse at Mr. Chuzzlewit’s nephew Chevy Slyme and his companion Montague Tiggs, and how they get on in the world – and we finally see Mark Tapley pull through his scheme of leaving the Blue Dragon because this is so agreeable a place that there is hardly any merit in being “jolly“ while working there.

The chapter starts with young Martin and Pinch having a good morning’s work – Martin doing the task set by Mr. Pecksniff, and Pinch doing Mr. Pecksniff’s accounts –, and once again we can see what kind of friendship this is between the two men when we learn that Martin is merrily whistling tunes during his occupation without noticing or paying heed to the fact that Tom would probably do his work better if he were not disturbed by the other man’s forays into the land of harmony. Tom, however, would not point this out to Martin. In fact, our narrator summarizes the nature of the two men’s friendship like this:

“And indeed it may be observed of this friendship, such as it was, that it had within it more likely materials of endurance than many a sworn brotherhood that has been rich in promise; for so long as the one party found a pleasure in patronizing, and the other in being patronised (which was in the very essence of their respective characters), it was of all possible events among the least probable, that the twin demons, Envy and Pride, would ever arise between them. So in very many cases of friendship, or what passes for it, the old axiom is reversed, and like clings to unlike more than to like.“

When the narrator says, “or what passes for it“ does he do this to intimate to his readers that perhaps the relationship between Tom and Martin cannot be called a friendship? Be that as it may, the two friends – I’ll call them that – have not gone on for long in their occupations when they are interrupted by the arrival of Mr. Tigg, who at once uses all his rhetorical cannon to carry it all before him, an endeavour in which he were probably more likely to succeed, were his outward appearance less on the shady, threadbare, sleazy side. Tigg states that he has come to collect the money his friend Mr. Pecksniff promised to leave for him before his trip to London, and when Pinch and Martin make it clear to him that Mr. Pecksniff never left any note, any money or whatever for Tigg, that gentleman, quite unabashed, says that it is very annoying his friend Pecksniff should be so remiss in his promises. Tigg’s sense of entitlement seems to make a great impression on Tom, and when it finally becomes clear that Tigg and Slyme are being detained for the payment of their bill at the Blue Dragon – in fact, Mark Tapley is waiting outside to keep an eye on Tigg lest he should decide to refrain from showing up again at the inn where he has run up debts –, Martin says,

“‘Why, simply — I am ashamed to say — that this Mr Slyme is a relation of mine, of whom I never heard anything pleasant; and that I don’t want him here just now, and think he would be cheaply got rid of, perhaps, for three or four pounds. You haven’t enough money to pay this bill, I suppose?’“

What does this question show about young Martin Chuzzlewit? With regard to his family, but also with regard to his view of Tom?

Tom, of course, does not have the money ready, but he is sure that if they explain the matter to Mrs. Lupin, and tell her that they will be good for the amount owned, the landlady will take them up on their word. By the way, it soon becomes obvious that it is not so much at Mrs. Lupin’s behest that the two debtors are detained, but that Mark Tapley wants to make a point of it because he cannot abide down-and-out, seedy scroungers if they give themselves airs and boss around the likes of him. Their excursion to the Blue Dragon gives the two friends the opportunity of seeing Mr. Chevy Slyme, who is in a particularly derelict state – maybe a kind of hangover – and who is not less prolix than Tigg this time. He uses his rhetorical power to proclaim that it is a disgrace for a man of genius like him to stand indebted for an alehouse bill to two well-meaning (my interpretation!) strangers, and that they can be sure that he will never forgive them the audacity to come to his help.

It seems that in Mr. Slyme we have another fine specimen of the Chuzzlewit breed, one who may not live up to much but to his name. Our narrator once again makes an intrusive comment when it comes to Chevy Slyme:

“He might have added that he hated two sorts of men; all those who did him favours, and all those who were better off than himself; as in either case their position was an insult to a man of his stupendous merits. But he did not; for with the apt closing words above recited, Mr Slyme; of too haughty a stomach to work, to beg, to borrow, or to steal; yet mean enough to be worked or borrowed, begged or stolen for, by any catspaw that would serve his turn; too insolent to lick the hand that fed him in his need, yet cur enough to bite and tear it in the dark; with these apt closing words Mr Slyme fell forward with his head upon the table, and so declined into a sodden sleep.“

Apparently, Mr. Slyme’s behaviour seems to make an important point in the narrator’s view. What point could that be? Can we even go so far to point out similarities between the seedy Chevy on the one hand, and the wealthy Chuzzlewit patriarch on the other, with regard to how they see themselves and how they see others?

Mr. Tigg, by all means, professes that Mr. Slyme’s outbreak is to be seen as a sign of his genius and independence, and he is all admiration. He then begs the chance of a private conference with Mr. Pinch, which he uses to borrow some further money – the last resources Mr. Pinch has – from him. He makes such an elaborate show of noting down the particulars of when and how it is to be restored to Mr. Pinch that there can rest no doubt in Tom’s breast that for all appearances might be indicating, he is still dealing with a trustworthy gentleman.

Mr. Tigg has once again appeared in his role of an agent on Mr. Slyme’s behalf. He is the one who does the talking and worms himself into people’s confidences, who puts on a good show. – Does the character amuse you, or do you find him annoying? What might Tigg’s real attitude toward Slyme be: Does he really admire him so much that his does his bidding, or are there ulterior motives which make it seem useful to him to pass as a good friend of Chevy’s?

The chapter ends with Mark Tapley’s farewell conversation with Mrs. Lupin, and here it becomes clear that if he were so disposed he could successfully ask the widow’s hand in marriage. However, although he has a high regard for Mrs. Lupin, he still feels that to bind himself too early to a place and a situation would most probably make him an unhappy man and let him even become ungrateful for a wife like Mrs. Lupin. They part in a good understanding – the landlady saying that he has probably never been a truer friend to her than in this conversation, and offering him help whenever he might need it. In the morning, Mark Tapley leaves the place, with all the villagers, men, women, children, and last, but not least, dogs, bidding him farewell.

It is obvious, from the farewell given to Mark, that he is a very popular man in the village, and what we have seen of him so far will probably bias us towards him. What do you make of his idea that he has to prove his capacity of being “jolly“ in a place where jollity is not too easy to muster up? Is it a mere whim and fancy? Is it a psychological issue, or is there a philosophical thought behind it? What do you think of a man who leaves a comfortable and predictable life only to prove his mettle?

Here we get another glimpse at Mr. Chuzzlewit’s nephew Chevy Slyme and his companion Montague Tiggs, and how they get on in the world – and we finally see Mark Tapley pull through his scheme of leaving the Blue Dragon because this is so agreeable a place that there is hardly any merit in being “jolly“ while working there.

The chapter starts with young Martin and Pinch having a good morning’s work – Martin doing the task set by Mr. Pecksniff, and Pinch doing Mr. Pecksniff’s accounts –, and once again we can see what kind of friendship this is between the two men when we learn that Martin is merrily whistling tunes during his occupation without noticing or paying heed to the fact that Tom would probably do his work better if he were not disturbed by the other man’s forays into the land of harmony. Tom, however, would not point this out to Martin. In fact, our narrator summarizes the nature of the two men’s friendship like this:

“And indeed it may be observed of this friendship, such as it was, that it had within it more likely materials of endurance than many a sworn brotherhood that has been rich in promise; for so long as the one party found a pleasure in patronizing, and the other in being patronised (which was in the very essence of their respective characters), it was of all possible events among the least probable, that the twin demons, Envy and Pride, would ever arise between them. So in very many cases of friendship, or what passes for it, the old axiom is reversed, and like clings to unlike more than to like.“

When the narrator says, “or what passes for it“ does he do this to intimate to his readers that perhaps the relationship between Tom and Martin cannot be called a friendship? Be that as it may, the two friends – I’ll call them that – have not gone on for long in their occupations when they are interrupted by the arrival of Mr. Tigg, who at once uses all his rhetorical cannon to carry it all before him, an endeavour in which he were probably more likely to succeed, were his outward appearance less on the shady, threadbare, sleazy side. Tigg states that he has come to collect the money his friend Mr. Pecksniff promised to leave for him before his trip to London, and when Pinch and Martin make it clear to him that Mr. Pecksniff never left any note, any money or whatever for Tigg, that gentleman, quite unabashed, says that it is very annoying his friend Pecksniff should be so remiss in his promises. Tigg’s sense of entitlement seems to make a great impression on Tom, and when it finally becomes clear that Tigg and Slyme are being detained for the payment of their bill at the Blue Dragon – in fact, Mark Tapley is waiting outside to keep an eye on Tigg lest he should decide to refrain from showing up again at the inn where he has run up debts –, Martin says,

“‘Why, simply — I am ashamed to say — that this Mr Slyme is a relation of mine, of whom I never heard anything pleasant; and that I don’t want him here just now, and think he would be cheaply got rid of, perhaps, for three or four pounds. You haven’t enough money to pay this bill, I suppose?’“

What does this question show about young Martin Chuzzlewit? With regard to his family, but also with regard to his view of Tom?

Tom, of course, does not have the money ready, but he is sure that if they explain the matter to Mrs. Lupin, and tell her that they will be good for the amount owned, the landlady will take them up on their word. By the way, it soon becomes obvious that it is not so much at Mrs. Lupin’s behest that the two debtors are detained, but that Mark Tapley wants to make a point of it because he cannot abide down-and-out, seedy scroungers if they give themselves airs and boss around the likes of him. Their excursion to the Blue Dragon gives the two friends the opportunity of seeing Mr. Chevy Slyme, who is in a particularly derelict state – maybe a kind of hangover – and who is not less prolix than Tigg this time. He uses his rhetorical power to proclaim that it is a disgrace for a man of genius like him to stand indebted for an alehouse bill to two well-meaning (my interpretation!) strangers, and that they can be sure that he will never forgive them the audacity to come to his help.

It seems that in Mr. Slyme we have another fine specimen of the Chuzzlewit breed, one who may not live up to much but to his name. Our narrator once again makes an intrusive comment when it comes to Chevy Slyme:

“He might have added that he hated two sorts of men; all those who did him favours, and all those who were better off than himself; as in either case their position was an insult to a man of his stupendous merits. But he did not; for with the apt closing words above recited, Mr Slyme; of too haughty a stomach to work, to beg, to borrow, or to steal; yet mean enough to be worked or borrowed, begged or stolen for, by any catspaw that would serve his turn; too insolent to lick the hand that fed him in his need, yet cur enough to bite and tear it in the dark; with these apt closing words Mr Slyme fell forward with his head upon the table, and so declined into a sodden sleep.“

Apparently, Mr. Slyme’s behaviour seems to make an important point in the narrator’s view. What point could that be? Can we even go so far to point out similarities between the seedy Chevy on the one hand, and the wealthy Chuzzlewit patriarch on the other, with regard to how they see themselves and how they see others?

Mr. Tigg, by all means, professes that Mr. Slyme’s outbreak is to be seen as a sign of his genius and independence, and he is all admiration. He then begs the chance of a private conference with Mr. Pinch, which he uses to borrow some further money – the last resources Mr. Pinch has – from him. He makes such an elaborate show of noting down the particulars of when and how it is to be restored to Mr. Pinch that there can rest no doubt in Tom’s breast that for all appearances might be indicating, he is still dealing with a trustworthy gentleman.

Mr. Tigg has once again appeared in his role of an agent on Mr. Slyme’s behalf. He is the one who does the talking and worms himself into people’s confidences, who puts on a good show. – Does the character amuse you, or do you find him annoying? What might Tigg’s real attitude toward Slyme be: Does he really admire him so much that his does his bidding, or are there ulterior motives which make it seem useful to him to pass as a good friend of Chevy’s?

The chapter ends with Mark Tapley’s farewell conversation with Mrs. Lupin, and here it becomes clear that if he were so disposed he could successfully ask the widow’s hand in marriage. However, although he has a high regard for Mrs. Lupin, he still feels that to bind himself too early to a place and a situation would most probably make him an unhappy man and let him even become ungrateful for a wife like Mrs. Lupin. They part in a good understanding – the landlady saying that he has probably never been a truer friend to her than in this conversation, and offering him help whenever he might need it. In the morning, Mark Tapley leaves the place, with all the villagers, men, women, children, and last, but not least, dogs, bidding him farewell.

It is obvious, from the farewell given to Mark, that he is a very popular man in the village, and what we have seen of him so far will probably bias us towards him. What do you make of his idea that he has to prove his capacity of being “jolly“ in a place where jollity is not too easy to muster up? Is it a mere whim and fancy? Is it a psychological issue, or is there a philosophical thought behind it? What do you think of a man who leaves a comfortable and predictable life only to prove his mettle?

Chapter 8

Our narrator now takes us a little back in time and drops us off in the coach in which the eminent architect of our hearts and his two daughters travel towards London. Mr. Pecksniff loses no time regaling his daughters with cut-and-dry moral observations, for example likening people with coaches pursuing their way through life, but also casting a doubtful light on his character with observations like the following,

“[…] Mr Pecksniff justly observed — when he and his daughters had burrowed their feet deep in the straw, wrapped themselves to the chin, and pulled up both windows — it is always satisfactory to feel, in keen weather, that many other people are not as warm as you are. And this, he said, was quite natural, and a very beautiful arrangement; not confined to coaches, but extending itself into many social ramifications. ‘For’ (he observed), ‘if every one were warm and well–fed, we should lose the satisfaction of admiring the fortitude with which certain conditions of men bear cold and hunger. And if we were no better off than anybody else, what would become of our sense of gratitude; which,’ said Mr Pecksniff with tears in his eyes, as he shook his fist at a beggar who wanted to get up behind, ‘is one of the holiest feelings of our common nature.’“

Later, in a similar vein when he has enjoyed a good meal – the goodness consisting in not too slight a measure in the awareness that he paid a fixed price for it and that so he would increase his profit by tugging in mightily – he observes,

“‘The process of digestion, as I have been informed by anatomical friends, is one of the most wonderful works of nature. I do not know how it may be with others, but it is a great satisfaction to me to know, when regaling on my humble fare, that I am putting in motion the most beautiful machinery with which we have any acquaintance. I really feel at such times as if I was doing a public service. When I have wound myself up, if I may employ such a term,’ said Mr Pecksniff with exquisite tenderness, ‘and know that I am Going, I feel that in the lesson afforded by the works within me, I am a Benefactor to my Kind!’“

As journeys were bound to be like in those times of coach-travelling, their way to London is beset with various inconveniences, and Mr. Pecksniff’s humour, notwithstanding some mental and moral support he grants it by taking repeated draughts from a bottle of spirits in the dark of the coach, suffers so much that it lowers itself into peevishness at times, and this also happens when two men enter the coach. One of them points out, in a sharp, thin voice,

“‘Now mind, […] I and my son go inside, because the roof is full, but you agree only to charge us outside prices. It’s quite understood that we won’t pay more. Is it?’“

The two newcomers are old Anthony Chuzzlewit and his son Jonas, and immediately Mr Pecksniff is all beaming, and rather oily, sanctity, or sanctimoniousness, again. When Anthony points out to his son that it was good of him to see the opportunity of getting inside places at the expense of outside ones because travelling outside in such weather would surely have killed Anthony, the son winces as though he realized that his has unduly prolonged his father’s life. The narrator makes the following remark on Jonas Chuzzlewit,

“The education of Mr Jonas had been conducted from his cradle on the strictest principles of the main chance. The very first word he learnt to spell was ‘gain,’ and the second (when he got into two syllables), ‘money.’ But for two results, which were not clearly foreseen perhaps by his watchful parent in the beginning, his training may be said to have been unexceptionable. One of these flaws was, that having been long taught by his father to over–reach everybody, he had imperceptibly acquired a love of over–reaching that venerable monitor himself. The other, that from his early habits of considering everything as a question of property, he had gradually come to look, with impatience, on his parent as a certain amount of personal estate, which had no right whatever to be going at large, but ought to be secured in that particular description of iron safe which is commonly called a coffin, and banked in the grave.“

Apparently, no one in the Chuzzlewit family is quite at ease with anybody else of that clan being around, and they all seem to fear that one of their relations will outwit and profit from them. Remembering that, what can be expected from a son like Jonas with regard to further events in the novel?

Jonas soon starts flirting in a very awkward, ugly-goblin-like way with the two Miss Pecksniffs, but it is obvious that his main interest is directed at Mercy and that the attentions paid to Cherry are probably more in the nature of an investment to reach an aim beyond that investment itself. Merry is not too impressed with Jonas’s advances and she makes fun of him, laughing at him all the time. While this is going on, Anthony tells Pecksniff that he meant no harm by calling him a hypocrite because, in his view, all people in the world are hypocrites, but that Mr. Pecksniff carries hypocrisy a little too far. He concludes,

“‘Why, the annoying quality in YOU, is […] that you never have a confederate or partner in YOUR juggling; you would deceive everybody, even those who practise the same art; and have a way with you, as if you — he, he, he! — as if you really believed yourself. I’d lay a handsome wager now,’ said the old man, ‘if I laid wagers, which I don’t and never did, that you keep up appearances by a tacit understanding, even before your own daughters here. Now I, when I have a business scheme in hand, tell Jonas what it is, and we discuss it openly. You’re not offended, Pecksniff?’“

What do you think? Has Anthony instinctively seen through Pecksniff here? And is his relationship towards his son based on a sounder ground of honesty?

Finally, the journey has ended, and the company are in London, where they each go their own ways for the time being. It is quite obvious, however, that they will meet again. In what direction do you think the plot will go here?

The two Miss Pecksniffs‘ first impression of London is not too glorious, the morning being cold, dark and wintry, and the boarding-house where they are going to put up, led by Mrs. Todgers, a woman with whom Mr. Pecksniff seems to be on familiar terms, being rather shabby. As Mrs. Todgers says, she usually exclusively takes up single gentlemen, who are in London on business, but since Mr. Pecksniff is such a good friend and customer of hers, she will go to any length in order to make an exception. While she makes professions of how sweet and charming the two daughters are, and of how they remind her of her mother, whom she has never seen, she keeps thinking about how she can actually accommodate the two female guests, and so she keeps looking at the two girls, “with affection beaming in one eye, and calculation shining out of the other.“

What do you think of Mrs. Todgers? Is her position a very enviable one? What might she really think of Pecksniff and his two daughters? What do we learn about the establishment she runs? How does the narrator give us an impression of everyday life at Mrs. Todgers’s boarding-house in these first pages?

Our narrator now takes us a little back in time and drops us off in the coach in which the eminent architect of our hearts and his two daughters travel towards London. Mr. Pecksniff loses no time regaling his daughters with cut-and-dry moral observations, for example likening people with coaches pursuing their way through life, but also casting a doubtful light on his character with observations like the following,

“[…] Mr Pecksniff justly observed — when he and his daughters had burrowed their feet deep in the straw, wrapped themselves to the chin, and pulled up both windows — it is always satisfactory to feel, in keen weather, that many other people are not as warm as you are. And this, he said, was quite natural, and a very beautiful arrangement; not confined to coaches, but extending itself into many social ramifications. ‘For’ (he observed), ‘if every one were warm and well–fed, we should lose the satisfaction of admiring the fortitude with which certain conditions of men bear cold and hunger. And if we were no better off than anybody else, what would become of our sense of gratitude; which,’ said Mr Pecksniff with tears in his eyes, as he shook his fist at a beggar who wanted to get up behind, ‘is one of the holiest feelings of our common nature.’“

Later, in a similar vein when he has enjoyed a good meal – the goodness consisting in not too slight a measure in the awareness that he paid a fixed price for it and that so he would increase his profit by tugging in mightily – he observes,

“‘The process of digestion, as I have been informed by anatomical friends, is one of the most wonderful works of nature. I do not know how it may be with others, but it is a great satisfaction to me to know, when regaling on my humble fare, that I am putting in motion the most beautiful machinery with which we have any acquaintance. I really feel at such times as if I was doing a public service. When I have wound myself up, if I may employ such a term,’ said Mr Pecksniff with exquisite tenderness, ‘and know that I am Going, I feel that in the lesson afforded by the works within me, I am a Benefactor to my Kind!’“

As journeys were bound to be like in those times of coach-travelling, their way to London is beset with various inconveniences, and Mr. Pecksniff’s humour, notwithstanding some mental and moral support he grants it by taking repeated draughts from a bottle of spirits in the dark of the coach, suffers so much that it lowers itself into peevishness at times, and this also happens when two men enter the coach. One of them points out, in a sharp, thin voice,

“‘Now mind, […] I and my son go inside, because the roof is full, but you agree only to charge us outside prices. It’s quite understood that we won’t pay more. Is it?’“

The two newcomers are old Anthony Chuzzlewit and his son Jonas, and immediately Mr Pecksniff is all beaming, and rather oily, sanctity, or sanctimoniousness, again. When Anthony points out to his son that it was good of him to see the opportunity of getting inside places at the expense of outside ones because travelling outside in such weather would surely have killed Anthony, the son winces as though he realized that his has unduly prolonged his father’s life. The narrator makes the following remark on Jonas Chuzzlewit,

“The education of Mr Jonas had been conducted from his cradle on the strictest principles of the main chance. The very first word he learnt to spell was ‘gain,’ and the second (when he got into two syllables), ‘money.’ But for two results, which were not clearly foreseen perhaps by his watchful parent in the beginning, his training may be said to have been unexceptionable. One of these flaws was, that having been long taught by his father to over–reach everybody, he had imperceptibly acquired a love of over–reaching that venerable monitor himself. The other, that from his early habits of considering everything as a question of property, he had gradually come to look, with impatience, on his parent as a certain amount of personal estate, which had no right whatever to be going at large, but ought to be secured in that particular description of iron safe which is commonly called a coffin, and banked in the grave.“

Apparently, no one in the Chuzzlewit family is quite at ease with anybody else of that clan being around, and they all seem to fear that one of their relations will outwit and profit from them. Remembering that, what can be expected from a son like Jonas with regard to further events in the novel?

Jonas soon starts flirting in a very awkward, ugly-goblin-like way with the two Miss Pecksniffs, but it is obvious that his main interest is directed at Mercy and that the attentions paid to Cherry are probably more in the nature of an investment to reach an aim beyond that investment itself. Merry is not too impressed with Jonas’s advances and she makes fun of him, laughing at him all the time. While this is going on, Anthony tells Pecksniff that he meant no harm by calling him a hypocrite because, in his view, all people in the world are hypocrites, but that Mr. Pecksniff carries hypocrisy a little too far. He concludes,

“‘Why, the annoying quality in YOU, is […] that you never have a confederate or partner in YOUR juggling; you would deceive everybody, even those who practise the same art; and have a way with you, as if you — he, he, he! — as if you really believed yourself. I’d lay a handsome wager now,’ said the old man, ‘if I laid wagers, which I don’t and never did, that you keep up appearances by a tacit understanding, even before your own daughters here. Now I, when I have a business scheme in hand, tell Jonas what it is, and we discuss it openly. You’re not offended, Pecksniff?’“

What do you think? Has Anthony instinctively seen through Pecksniff here? And is his relationship towards his son based on a sounder ground of honesty?

Finally, the journey has ended, and the company are in London, where they each go their own ways for the time being. It is quite obvious, however, that they will meet again. In what direction do you think the plot will go here?

The two Miss Pecksniffs‘ first impression of London is not too glorious, the morning being cold, dark and wintry, and the boarding-house where they are going to put up, led by Mrs. Todgers, a woman with whom Mr. Pecksniff seems to be on familiar terms, being rather shabby. As Mrs. Todgers says, she usually exclusively takes up single gentlemen, who are in London on business, but since Mr. Pecksniff is such a good friend and customer of hers, she will go to any length in order to make an exception. While she makes professions of how sweet and charming the two daughters are, and of how they remind her of her mother, whom she has never seen, she keeps thinking about how she can actually accommodate the two female guests, and so she keeps looking at the two girls, “with affection beaming in one eye, and calculation shining out of the other.“

What do you think of Mrs. Todgers? Is her position a very enviable one? What might she really think of Pecksniff and his two daughters? What do we learn about the establishment she runs? How does the narrator give us an impression of everyday life at Mrs. Todgers’s boarding-house in these first pages?

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 7

Here we get another glimpse at Mr. Chuzzlewit’s nephew Chevy Slyme and his companion Montague Tiggs, and how they get on in the world – and we finally see Mark Tapley pull through his sc..."

Tiggs reminds me of Gashford a lot. I am sure he has his own agenda, and is good at putting up the facade of loyal friend/servant of someone to use that person as a kind of stepping stone to himself. I cannot imagine another reason to sing Slyme's praises like he does.

Here we get another glimpse at Mr. Chuzzlewit’s nephew Chevy Slyme and his companion Montague Tiggs, and how they get on in the world – and we finally see Mark Tapley pull through his sc..."

Tiggs reminds me of Gashford a lot. I am sure he has his own agenda, and is good at putting up the facade of loyal friend/servant of someone to use that person as a kind of stepping stone to himself. I cannot imagine another reason to sing Slyme's praises like he does.

I do believe that Mrs. Todgers probably is not enviable. She seems to be dependent on Pecksniff somehow, seen how she goes above and beyond to accomodate him and his daughters. She has to rent parts of her house out to strangers, up to a point that she even has to give up her own rooms to the Pecksniff girls. Dickens has a way of showing how horrid the surroundings are, by the view from Mrs. Todgers' room and how the door to her parlor can hardly be opened - I guess because of cold, or damp, or both. I do believe she has the better end of the bargain compared to many other single older women/widows in that city in that time though.

I'm still not sure if I like Martin Jr. - I still mostly feel like I want to slap him in the face for being so self-centered, but I also realize he might mean well, and just doesn't know how bad he's doing. Anthony and Jonas Chuzzlewit can still go either way as well - or they turn out to be very funny, or they turn out to be very villainous, or both.

I'm still not sure if I like Martin Jr. - I still mostly feel like I want to slap him in the face for being so self-centered, but I also realize he might mean well, and just doesn't know how bad he's doing. Anthony and Jonas Chuzzlewit can still go either way as well - or they turn out to be very funny, or they turn out to be very villainous, or both.

Tristram wrote: "we are going to see how Mr. Pinch and young Martin Chuzzlewit, the new pupil at Mr. Pecksniff’s, get along with each other..."

Tristram wrote: "we are going to see how Mr. Pinch and young Martin Chuzzlewit, the new pupil at Mr. Pecksniff’s, get along with each other..."As of now, I'm of the opinion that Martin is just young and immature. I think his heart is probably good, but he just doesn't realize how entitled he's been, and he's still living with that mind-frame even now that he's been cut off. Something will have to occur to open his eyes and get a clearer picture of the world around him, including Tom's goodness.

Once again, Dickens shows his astute observation of human nature when he describes "what passes for" their friendship. I've known friendships like this, which have gone along quite nicely until the Pinch decides that he no longer enjoys that subservient role. I wonder if Tom will reach that point with Martin, or if he'll remain content to always be the sidekick. In a modern novel, there would be a satisfying scene in which Tom finally stands up for himself, but I'm not sure if Dickens will give us that moment.

I laughed out loud when Pinch suggested that Martin was "obstinate" and Martin, taken aback, insisted that he, instead, had a "determined firmness." There were spin doctors even in the Victorian age. :-)

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 7

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 7Mr. Chuzzlewit’s nephew Chevy Slyme and his companion Montague Tiggs..."

I still haven't figured Tiggs and Slyme out. They have some kind of symbiotic relationship, but we haven't been given enough information to know what they get from one another. Having a servant - even a child (like the Marchioness in The Old Curiosity Shop) or someone like Tiggs or (excuse the comparison) Sam Weller raises Slyme's status. But is Tiggs actually a servant, or an accomplice?

What do you think of a man [Mark] who leaves a comfortable and predictable life only to prove his mettle?

I looked it up, and there don't seem to have been any wars going on for England in 1844 when this was published. It just seemed like soldiering might have been right up Mark's alley, and would have made more sense to the reader than this odd circumstance of a man with a rosy personality searching for some horrible situation instead of settling somewhere like the Blue Dragon where he is happy and well-regarded. Hard as it is not to like Mark, I feel very sorry for Mrs. Lupin. She seems to "get" him, though, and is wise to not try to hold him there.

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 8

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 8What do you think of Mrs. Todgers? ..."

My initial thought was that she'd set her cap at Pecksmith. It would certainly explain why she tried to be so accommodating, and wanted to endear herself to the Pecksniff sisters.

Jonas is gross and creepy. Merry better watch out for him.

Merry is starting to remind me a bit of Kitty Bennet in Pride and Prejudice. If I had to pick a Bennet sister for Charity, I suppose it would be the bookish one - Mary.

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "we are going to see how Mr. Pinch and young Martin Chuzzlewit, the new pupil at Mr. Pecksniff’s, get along with each other..."

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "we are going to see how Mr. Pinch and young Martin Chuzzlewit, the new pupil at Mr. Pecksniff’s, get along with each other..."As of now, I'm of the opinion that Martin is just yo..."

Hi Mary Lou, I agree with your interpretation of Martin. He certainly seems immature and self-absorbed, which makes me think that Dickens is setting him up for a fall (perhaps his stubbornness is his hamartia?). I particularly like the moment you point out where Martin is unable to realize his own obstinacy. A few lines before that, Martin describes his grandfather’s worst traits: “In the first place, he has the most confirmed obstinacy of character you ever met with in any human creature. In the second, he is most abominably selfish.” Martin then brags a few lines later, “All I have to do, you know, is to be very thankful that they haven’t descended to me, and to be very careful that I don’t contract ‘em.”

However, it’s clear from the way Martin handles his engagement with Mary that he is, right now, both obstinate and selfish. For me, it’s obvious to see how Martin and Pecksniff are related (they’re both hypocrites, but in different ways - Pecksniff is much more calculating).

Tristram, while reading your comments something triggered a memory of grump 1 and grump 2 having a wonderful argument just about this same place when we read the book the first time. I had such a strong feeling about this that I went back and looked it up. I was right, it was wonderful, here's some of it.

Everyman wrote:

Tristram wrote: "My dear Fellow Pickwickians,

not quite unlike the coach that is taking Mr. Pecksniff and his charming daughters to London, we are moving on into the story, drawn by the Pegasus of our imagination ..."

That is the most awful, terrible, ignorant, imbecilic, weakest, disgraceful post I have ever read in my life. Every word of it is false, wrong, totally off the mark. There is not a word, nay not a syllable, nay not a letter of it I can agree with.

There, Kim, was that better?

****************************************************************

Everyman wrote:Tristram wrote: "All in all, we still do not have anything like a story-line as yet - but I have not felt bored at all. "

Despite previous post, I agree with the first phrase, but not the second. I had a hard time keeping my eyes open during these three chapters.

Having found a sarcastic voice for presenting Pecksniff, Dickens reprises the same sarcastic voice for the younger Martin. Claiming that he is neither selfish nor obstinate, when it is clear from his behavior that he is both in spades. Sarcasm is like hot sauce. A little, deftly applied, can be good. A lot can never be.

I wonder whether Dickens knew a boy named Tom or Pinch (he wouldn't dare use the full name) who bullied him and on whom Dickens is taking his revenge. He takes the sweetest man imaginable and has everybody take advantage of him, lie to him, walk all over him, abuse him, and he still smiles through it all. If Mark could spend a day in Tom Pinch's place, he would be happy as a clam. There is something wrong in Dickens's soul that he can treat Pinch as he does.

So, Tristram, you're not bored by this. But dare you say you are actually enjoying it? If you can, I can only ascribe it to the stereotypical view of Germans as morose and addicted to the dark side of literature (witness Goerthe, Mann, Nietzsche, et. al. Has there ever existed a cheerful German author? Is it conceivable that Germany could have created a Wodehouse?)

I hope that wasn't obnoxious (except to the extent that it satisfies Kim's need for us to oppose each other). But really, how anybody can actually enjoy MC, up to this point, really does escape me.

**************************************************************

Tristram wrote:

Well, sir, your most slandering, reviling, calumnious, and - let's not forget this - tautological denunciation of my carefully considered and, as others have told me repeatedly and in all sobriety, well-measured and edifying lines makes it crystal-clear to anyone whose spirit is open to the finer vibrations of art and poetry that you must be in league with the Eatanswill Gazette, whose buffoon of an editor would pass a dying frog without any sense of Melpomene herself touching his heart.

You may therefore rest assured that I would not hinder anyone calling you a humbug, sir!

******************************************************************

Tristram wrote:

I do like it grim, satirical, gothic even, and you are right ... this is typically German in that there was a certain stream in German Romanticism that was interested in the morbid and grotesque side of life. However, I am not so sure if the authors you named can be seen as "dark". Goethe is far too multi-faceted to reduce him to the dreary tale of Werther, for instance, and Nietzsche is anything but pessimistic. He happens to be one of my favourite ... I hesitate to say "philosophers" because he is far too unsystematic and too enigmatic to be called a "philosopher" in the strongest sense of the word, so let's just say, He happens to be one of my favourite guys. It would lead too far now to point out Nietzsche's elementary sense of yes-siness towards life as such, but we may always open a side thread.

As to Mann, I would not know because I have not managed to read more than a few pages of him, in which he managed to come over as a stuck-up word-juggler who is uncommonly full of himself. There is something that I frankly dislike about his style, which would probably have had me extend this feeling of dislike to his person as well if ever I had had the mischance of meeting him.

************************************************************

Kim wrote:

Everyman and Tristram:

Oh thank you both for saying those things to each other!!! I was getting so worried about the both of you, you've both been so yuckily nice to each other lately. I thought you may not be feeling well, but then Everyman had the wonderful post using words such as awful, terrible, ignorant so I knew he was fine; however I was still worried about you Tristram because it took a little while for you to respond and Everyman was clearly in first place by then; however you have now brilliantly caught him with words equal to his such as slandering, reviling, calumnious; and once again are tied. Grumps. :-}

************************************************************

Tristram wrote:

Well, I can't speak for Everyman, but I surely do whatever I can not to disappoint you ;-)

*****************************************************************

Everyman wrote:

Well, it's very challenging for me to act grumpy; goes so much against my natural cheerfulness. But when I'm desperate to find some source of grumpiness, I just think of Christmas decorating, and that does it; total grumpiness and depression par excellance.

******************************************************************

I miss the two of you together. :-(

Everyman wrote:

Tristram wrote: "My dear Fellow Pickwickians,

not quite unlike the coach that is taking Mr. Pecksniff and his charming daughters to London, we are moving on into the story, drawn by the Pegasus of our imagination ..."

That is the most awful, terrible, ignorant, imbecilic, weakest, disgraceful post I have ever read in my life. Every word of it is false, wrong, totally off the mark. There is not a word, nay not a syllable, nay not a letter of it I can agree with.

There, Kim, was that better?

****************************************************************

Everyman wrote:Tristram wrote: "All in all, we still do not have anything like a story-line as yet - but I have not felt bored at all. "

Despite previous post, I agree with the first phrase, but not the second. I had a hard time keeping my eyes open during these three chapters.

Having found a sarcastic voice for presenting Pecksniff, Dickens reprises the same sarcastic voice for the younger Martin. Claiming that he is neither selfish nor obstinate, when it is clear from his behavior that he is both in spades. Sarcasm is like hot sauce. A little, deftly applied, can be good. A lot can never be.

I wonder whether Dickens knew a boy named Tom or Pinch (he wouldn't dare use the full name) who bullied him and on whom Dickens is taking his revenge. He takes the sweetest man imaginable and has everybody take advantage of him, lie to him, walk all over him, abuse him, and he still smiles through it all. If Mark could spend a day in Tom Pinch's place, he would be happy as a clam. There is something wrong in Dickens's soul that he can treat Pinch as he does.

So, Tristram, you're not bored by this. But dare you say you are actually enjoying it? If you can, I can only ascribe it to the stereotypical view of Germans as morose and addicted to the dark side of literature (witness Goerthe, Mann, Nietzsche, et. al. Has there ever existed a cheerful German author? Is it conceivable that Germany could have created a Wodehouse?)

I hope that wasn't obnoxious (except to the extent that it satisfies Kim's need for us to oppose each other). But really, how anybody can actually enjoy MC, up to this point, really does escape me.

**************************************************************

Tristram wrote:

Well, sir, your most slandering, reviling, calumnious, and - let's not forget this - tautological denunciation of my carefully considered and, as others have told me repeatedly and in all sobriety, well-measured and edifying lines makes it crystal-clear to anyone whose spirit is open to the finer vibrations of art and poetry that you must be in league with the Eatanswill Gazette, whose buffoon of an editor would pass a dying frog without any sense of Melpomene herself touching his heart.

You may therefore rest assured that I would not hinder anyone calling you a humbug, sir!

******************************************************************

Tristram wrote:

I do like it grim, satirical, gothic even, and you are right ... this is typically German in that there was a certain stream in German Romanticism that was interested in the morbid and grotesque side of life. However, I am not so sure if the authors you named can be seen as "dark". Goethe is far too multi-faceted to reduce him to the dreary tale of Werther, for instance, and Nietzsche is anything but pessimistic. He happens to be one of my favourite ... I hesitate to say "philosophers" because he is far too unsystematic and too enigmatic to be called a "philosopher" in the strongest sense of the word, so let's just say, He happens to be one of my favourite guys. It would lead too far now to point out Nietzsche's elementary sense of yes-siness towards life as such, but we may always open a side thread.

As to Mann, I would not know because I have not managed to read more than a few pages of him, in which he managed to come over as a stuck-up word-juggler who is uncommonly full of himself. There is something that I frankly dislike about his style, which would probably have had me extend this feeling of dislike to his person as well if ever I had had the mischance of meeting him.

************************************************************

Kim wrote:

Everyman and Tristram:

Oh thank you both for saying those things to each other!!! I was getting so worried about the both of you, you've both been so yuckily nice to each other lately. I thought you may not be feeling well, but then Everyman had the wonderful post using words such as awful, terrible, ignorant so I knew he was fine; however I was still worried about you Tristram because it took a little while for you to respond and Everyman was clearly in first place by then; however you have now brilliantly caught him with words equal to his such as slandering, reviling, calumnious; and once again are tied. Grumps. :-}

************************************************************

Tristram wrote:

Well, I can't speak for Everyman, but I surely do whatever I can not to disappoint you ;-)

*****************************************************************

Everyman wrote:

Well, it's very challenging for me to act grumpy; goes so much against my natural cheerfulness. But when I'm desperate to find some source of grumpiness, I just think of Christmas decorating, and that does it; total grumpiness and depression par excellance.

******************************************************************

I miss the two of you together. :-(

Chapter 6

Chapter 6The narrative descriptions and characters are drawing my attention. The story itself has not yet grabbed me, but Martin professing his love for Mary has begun to do so.

1. Should we trust young Martin? Does the tale of woe he tells Tom come close to the truth? Martin is self-absorbed, a little arrogant, and is probably getting cross-eyed looking down his nose at Tom. But is he truthful?

2. I thought Mrs. Lupin, the landlady, described Mary as plain.

3. Love that opening description of Charity's personality being marred by a squirt of lemon into it.

4. Laughed at the Fill-In-The-Word game Tom plays with Martin. No, not obstinate. Firmness.

Mary Lou wrote: "I laughed out loud when Pinch suggested that Martin was "obstinate" and Martin, taken aback, insisted that he, instead, had a "determined firmness." There were spin doctors even in the Victorian age. :-)"

Mary Lou wrote: "I laughed out loud when Pinch suggested that Martin was "obstinate" and Martin, taken aback, insisted that he, instead, had a "determined firmness." There were spin doctors even in the Victorian age. :-)"Hee Hee!

Looks like Martin has potential. It's all in the words you use.

Mary Lou wrote: "Merry is starting to remind me a bit of Kitty Bennet in Pride and Prejudice.

Mary Lou wrote: "Merry is starting to remind me a bit of Kitty Bennet in Pride and Prejudice.Oooh, good catch, Mary Lou.

Kim wrote: " Everyman and Tristram..."

Kim wrote: " Everyman and Tristram..."I hadn't yet joined the group when this exchange occurred, so thank you for sharing it, Kim! Whether one agreed with Everyman's comments or not, he always gave us plenty to think about, and he was never shy about sharing his opinions! When he and Tristram got going, I never failed to learn something - even if it was just a couple of new vocabulary words. :-)

Mark Tapley is a weird guy. Mrs. Lupin would do good to not marry him, sex or no sex. But he is certainly well liked. That was quite a goodbye awaiting him.

Mark Tapley is a weird guy. Mrs. Lupin would do good to not marry him, sex or no sex. But he is certainly well liked. That was quite a goodbye awaiting him.

Huh. I always assumed Slyme was like slime. Slimy never occurred to me, but not that you've brought it up I'm questioning myself. But you're right, that either one would be an accurate description.

Huh. I always assumed Slyme was like slime. Slimy never occurred to me, but not that you've brought it up I'm questioning myself. But you're right, that either one would be an accurate description.

I’ve been thinking on the question about my thoughts on Pecksniff, and this led me to comparing him to Nicholas Nicklebys Squeers (apologies if anyone’s brought this comparison up before); the stripped back essence of what they’re doing as characters-misleading naive families/younger people to part with their money/talent in exchange for the bear minimum in return (with a dollop of contempt thrown in)-is very similar, but Pecksniff has more awareness of how he’s perceived. I found this interesting as my gut reaction would be that Squeers was the most evil of the two, but on reflection perhaps they’re level-the power of some good PR!

I’ve been thinking on the question about my thoughts on Pecksniff, and this led me to comparing him to Nicholas Nicklebys Squeers (apologies if anyone’s brought this comparison up before); the stripped back essence of what they’re doing as characters-misleading naive families/younger people to part with their money/talent in exchange for the bear minimum in return (with a dollop of contempt thrown in)-is very similar, but Pecksniff has more awareness of how he’s perceived. I found this interesting as my gut reaction would be that Squeers was the most evil of the two, but on reflection perhaps they’re level-the power of some good PR!I definitely feel for Tom Pinch too-he just comes across as having been so beaten down over the years that he’s now totally accepting of the place others have put him in to. I was rather annoyed to see young Martin lapse into this very quickly (to a lesser extent admittedly), but will give him the benefit of the doubt for now and put it down to a lack of self awareness and being particularly impressionable (picking up from the Pecksniff family). I agree with Mary Lou that I’d be surprised to see Pinch get his big standing up moment, but I do hope we get to see him at least realise this and choose to do something for his own good (finally).

Chris wrote: "I’ve been thinking on the question about my thoughts on Pecksniff, and this led me to comparing him to Nicholas Nicklebys Squeers (apologies if anyone’s brought this comparison up before); the stri..."

Chris wrote: "I’ve been thinking on the question about my thoughts on Pecksniff, and this led me to comparing him to Nicholas Nicklebys Squeers (apologies if anyone’s brought this comparison up before); the stri..."Interesting comparison, Chris. They're so differently packaged, if you know what I mean, that the similarities never occurred to me. Of course, Pecksniff isn't violent (yet, at least), so Squeers wins the who's-more-awful prize. In fact, based on the wind overpowering Pecksniff in that early chapter, he doesn't come across as physically powerful or aggressive. But he does know how to dupe his students and their parents.

Mary Lou wrote: "Huh. I always assumed Slyme was like slime. Slimy never occurred to me, but not that you've brought it up I'm questioning myself. But you're right, that either one would be an accurate description."

Mary Lou wrote: "Huh. I always assumed Slyme was like slime. Slimy never occurred to me, but not that you've brought it up I'm questioning myself. But you're right, that either one would be an accurate description."Or even Sly-Me like in I am a sly one. Three possibilities.

Thanks Mary Lou-I’d somehow managed to forget Squeers’ beatings (it’s been a while since I read NN!), which definitely swings it; Pecksniff doesn’t come across as that type of character.

Thanks Mary Lou-I’d somehow managed to forget Squeers’ beatings (it’s been a while since I read NN!), which definitely swings it; Pecksniff doesn’t come across as that type of character.

Given Slyme's station in life and the two types of people he hates most, I think it safe to say he hates almost everyone, including everyone in his family. That's as good an indicator of his character going forward as any.

Given Slyme's station in life and the two types of people he hates most, I think it safe to say he hates almost everyone, including everyone in his family. That's as good an indicator of his character going forward as any. So, is Tiggs not doing Slyme favors? Or, more likely, has Slyme promised Tiggs some large reward in return for his services? And wouldn't that large reward have to be the older Martin's money?

Kim wrote: "I miss the two of you together. :-("

Same here! He was, just like Dickens, inimitable!

Same here! He was, just like Dickens, inimitable!

About Chevy Slyme and Tiggs: It's difficult to make out which one of the two is the dog and which one is the tail. Tiggs is rather verbose and glib whereas Slyme is just whiny, all in all. Is there not also a scene when Tiggs bids Slyme to go and wait round the corner for a while again, while some transactions are to be made with Mr. Pecksniff? This would imply that Mr. Tiggs is doing the bidding and Mr. Slyme the obeying. Maybe, Tiggs has just decided to tag himself on to Mr. Slyme because the latter is related to the wealthy Martin Chuzzlewit and there might be the chance of money coming down on Slyme?

About Tom Pinch and how we read him: As Mary Lou pointed out, a modern writer would have Tom turn against Martin's carelessness and patronizing and assert himself sooner or later. Simply because modern readers would probably expect such a thing and because modern notions emphasize every person's basic equality. An interesting question would be whether a Victorian reader would have had the same expectations. A more interesting question would be how to find this out ;-)

About Tom Pinch and how we read him: As Mary Lou pointed out, a modern writer would have Tom turn against Martin's carelessness and patronizing and assert himself sooner or later. Simply because modern readers would probably expect such a thing and because modern notions emphasize every person's basic equality. An interesting question would be whether a Victorian reader would have had the same expectations. A more interesting question would be how to find this out ;-)

Chapter 8

Chapter 8England is being overrun by Chuzzlewits; they are everywhere.

Did Mr. Pecksniff get a bit tipsy after drinking a copious amount of liquor?

Jinkens whistling while he works is a bit jolly, wouldn't you say?

Mr. Pinch and the New Pupil on a Social Occasion

Chapter 6

Phiz

March 1843

Text Illustrated:

Martin Chuzzlewit beheld these roystering preparations with infinite contempt, and stirring the fire into a blaze (to the great destruction of Mr Pecksniff’s coals), sat moodily down before it, in the most comfortable chair he could find. That he might the better squeeze himself into the small corner that was left for him, Mr Pinch took up his position on Miss Mercy Pecksniff’s stool, and setting his glass down upon the hearthrug and putting his plate upon his knees, began to enjoy himself.

If Diogenes coming to life again could have rolled himself, tub and all, into Mr Pecksniff’s parlour and could have seen Tom Pinch as he sat on Mercy Pecksniff’s stool with his plate and glass before him he could not have faced it out, though in his surliest mood, but must have smiled good-temperedly. The perfect and entire satisfaction of Tom; his surpassing appreciation of the husky sandwiches, which crumbled in his mouth like saw-dust; the unspeakable relish with which he swallowed the thin wine by drops, and smacked his lips, as though it were so rich and generous that to lose an atom of its fruity flavour were a sin; the look with which he paused sometimes, with his glass in his hand, proposing silent toasts to himself; and the anxious shade that came upon his contented face when, after wandering round the room, exulting in its uninvaded snugness, his glance encountered the dull brow of his companion; no cynic in the world, though in his hatred of its men a very griffin, could have withstood these things in Thomas Pinch.

Some men would have slapped him on the back, and pledged him in a bumper of the currant wine, though it had been the sharpest vinegar — aye, and liked its flavour too; some would have seized him by his honest hand, and thanked him for the lesson that his simple nature taught them. Some would have laughed with, and others would have laughed at him; of which last class was Martin Chuzzlewit, who, unable to restrain himself, at last laughed loud and long.

"That’s right," said Tom, nodding approvingly. "Cheer up! That’s capital!" [Chapter VI, "Comprises, among other important matters, Pecksniffian and architectural, an exact relation of the progress made by Mr. Pinch in the confidence and friendship of the New Pupil," pp. 69-70 in the 1844 edition; descriptive headline in both the 1868 and 1897 editions: "The New Pupil Confides"]

Commentary:

This illustration intensifies the inherent comedy of the text. For instance, not one but two likenesses of Seth Pecksniff, readily identified by his long face and spiky hair, mildly glance down at the apprentices. Whereas bald-pated, plain-featured Tom appreciatively studies the contents of his small glass, his tall, lean, handsome companion with a Byronic hairstyle seems to staring at something in the flames — perhaps his own uncertain future. In place of conventional art on the walls (landscapes and family portraits) Pecksniff has placed four architectural designs, each bearing his name. The angry young man has already consumed his small glass of wine, and does not respond to his amiable companion, who has occupied the footstool because his pensive friend has taken the only chair in front of the flaming coals.

Young Martin broods over the supposed injustice of his having been relegated to a remote Wilshire village, although his circumstances would seem to be comfortable enough as he sits before a good fire with a glass of wine and an affable companion. As Michael Steig notes, the young man's wounded egotism has resulted in his dark mood in a room filled by the silent presence of the "master" in the objects surrounding him:

The room is dominated by Mr. Pecksniff through effigies of himself on three sides: the "Portrait ... by Spiller" and "Bust by Spoker" (not referred to in the text until the next part, ch. 5, p. 61), and the drawings of three architectural designs bearing Pecksniff's name: a large heroic monument and two smaller buildings, one of which is mirrored in the form of the poor box (so labeled) on the chimneypiece. In its latter form, this building (which is probably intended for a workhouse) takes on the appearance of a glowering face. [Chapter 3, p. 64 (text of chapter)]

Phiz represents this parlor with its many embedded references to the village architect, as in Meekness of Mr. Pecksniff and His Charming Daughters (January 1843), as a sort of Pecksniffian museum, which offers mute testimonials to the self-congratulatory egotist. The bust, a likeness of the self-satisfied architect, looks directly down at the pensive student. In contrast, the face in the portrait (unobscured in the January illustration) mildly regards young Martin from the mantlepiece, peeping over the framed design for a village pump that is one of Pecksniff's specialties. Although Steig has not noted this difference, the brilliantly lit fireplace in the initial view of the room now discharges billowing smoke, which comments visually upon young Chuzzlewit's smoldering gaze. Phiz effectively demonstrates the differences in temperaments of Pecksniff's apprentices by their poses and facial expressions, which render them binary opposites — Tom Pinch the eternal optimist, cheerful and outgoing; young Martin, in contrast, a thorough malcontent who broods over real and imaged wrongs.

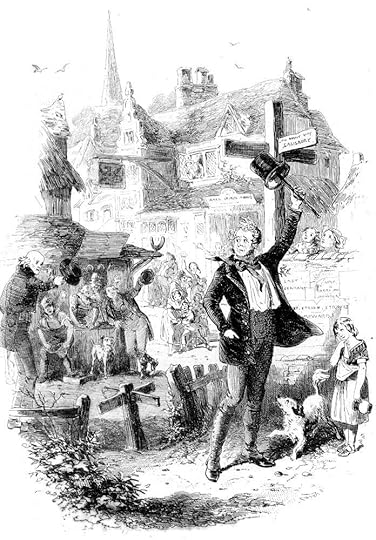

Mark Begins to be Jolly Under Creditable Circumstances

Chapter 7

Phiz

March 1843

Text Illustrated:

He rose early next morning, and was a-foot soon after sunrise. But it was of no use; the whole place was up to see Mark Tapley off; the boys, the dogs, the children, the old men, the busy people and the idlers; there they were, all calling out "Good-b'ye, Mark," after their own manner, and all sorry he was going. Somehow he had a kind of sense that his old mistress was peeping from her chamber-window, but he couldn't make up his mind to look back.

"Good-b'ye one, good-b'ye all!" cried Mark, waving his hat on the top of his walking-stick, as he strode at a quick pace up the little street. "Hearty chaps them wheelwrights — hurrah! Here's the butcher's dog a-coming out of the garden — down, old fellow! And Mr Pinch a-going to his organ — good-b'ye, sir! And the terrier-bitch from over the way — hie, then, lass! And children enough to hand down human natur to the latest posterity — good-b'ye, boys and girls! There's some credit in it now. I'm a-coming out strong at last. These are the circumstances that would try a ordinary mind; but I'm uncommon jolly. Not quite as jolly as I could wish to be, but very near. Good-b'ye! good-b'ye!" [Chapter VII, "In which Mr. Chevy Slyme asserts the independence of his spirit; and the Blue Dragon loses a limb," page 88 in the 1844 edition.]

Michael Steig's Commentary: Farewell to Village Life and the Widow Lupin (1978):

Browne's propensity for interpretation is evident in the signpost, an emblem which Dickens and Browne put to various uses. The signpost in this plate points in the opposite direction from Mark's stick and hat, which together seem to express the real direction of his feelings, back toward the village; the four-way signpost is mirrored by the shape of the turnstile that separates Mark from the village. The empty, tipped-over pitcher carried by the little girl could represent either the moral emptiness of Mark's willful abandonment of his community, or the "spilt milk" over which there's no use crying. Finally, the three posters comment on Mark's action: the upper two, "Last Appearance" and "Every Man in His Humour," as theatrical notices imply that Mark is playing a role, and the specific reference to Jonson suggests that Mark's "humor" is as foolish and as in need of deflation as that of Jonson's characters; the third poster, "Lost, Stolen, Strayed/Reward!" again ridicules Mark's need for "creditable" jollity, implying that he is deserting his proper place, like a strayed dog or sheep. [Steig, Chapter 3, pp. 66-67]

Commentary: And so to London and Abroad:

Although the ebullient Mark has risen early, in part, one suspects, to avoid tearful farewells, already the villagers, their children, several dogs, Tom Pinch (left) and the Widow Lupin herself (in the window, center) come to see him off. The plate's realization of the event parallels Dickens's description, except for the crowd of young admirers that Dickens implies in "children enough to hand down human nature to the latest posterity" (Ch. 7). This crowd scene set piece — a picaro's "departure" in a "progress" — has both drama and pathos without any sense of crowding. Phiz has filled in the blanks in Dickens's description of the departure scene, which occupies a mere half-page, and added the buildings but subtracted the garden.

Phiz communicates something of the energy of the dashes and reiterated "good-by'es" in the letterpress through the waving hands of Tom Pinch, the conclave of wheelwrights, and the crowd in front of the inn, all vividly realized in the clear air that we are soon to exchange for the London smog of Todgers's and vicinity. Phiz's humanizing touch appears in the lone child, right, whose posture, gesture, and facial expression reveal how much everyone in the little community will miss jolly Mark. His jacket blows in the stiff breeze from left to right, a wind of destiny that in agitating the bottom of his garment draws the eye to the significant words on the poster: "Lost, Stolen." Reiterating the left-to-right movement is the fingerpost above Mark's beaver, with the word "Salisbury" just decipherable. The church spire and the gables of the Blue Dragon reinforce the upward movement of Mark's figure, as if heaven, emigration, and the pursuit of jollity under trying circumstances are all connected.

The execution of the whole scene is an artistic tour de force, as J. R. Harvey remarks of the majority of Phiz's etchings in the narrative-pictorial series for Martin Chuzzlewit: here, unlike some of his plates for the two novels in Master Humphrey's Clock,

his work is crisp and bright. His figures are full-size and solid, and while he retains the acuteness and economy of his caricatures, he seems less concerned with caricaturing people and more with drawing them well. The biting-in has produced an unusually clean line that shows Browne's etching at its most sensitive; the line takes delicate curves yet looks as though it has been slit in the paper with a razor.

Mark Tapley, this picaresque novel's Sancho Panza figure, appears so obsessed with remaining "jolly" in the face of frustration, malevolence, and adversity seems a mere caricature at this point in the narrative. Nonetheless, Phiz has taken pains to individualize him in the March 1843 engraving Mark Begins to be Jolly Under Creditable Circumstances. From his tousled hair, swirling neck-cloth, neat leggings, and hat held jauntily aloft on a rather short walking-stick (a mere flourish to the travelling costume rather than a functional prop for this strapping giant) we have a clear conception of his style and manner; a significant touch is the slightly melancholy visage, betokening an inner conflict as he leaves the woman he has grown to love for an uncertain future. Phiz leaves us in no doubt that Mark is the subject of the picture, for his solid and robust figure fills the frame, from the dog in vigorous movement and the child in stasis at the bottom to the open sky above.

The illustration has the clean lines and delicate curves that characterize a well-bitten steel plate, implying a thoroughness of execution and attention to detail in every aspect of the process, from initial drawing through etching to printing. We note in Phiz's handling of the gabled Blue Dragon Inn the influence of antiquarian George Cattermole's A Very Aged, Ghostly Place and The Maypole Inn from Master Humphrey's Clock. The artist's discretely conceals his signature at the bottom right, immediately below the butcher's dog, whose bouncing gait and wagging tail add to the sense of urgency. Mark, despite feelings of uncertainty about his decisions and of pain at separation from a way of life, a people, and a place he has loved, must be off. The future (and, unbeknownst to Mark, at this point, America) beckons.

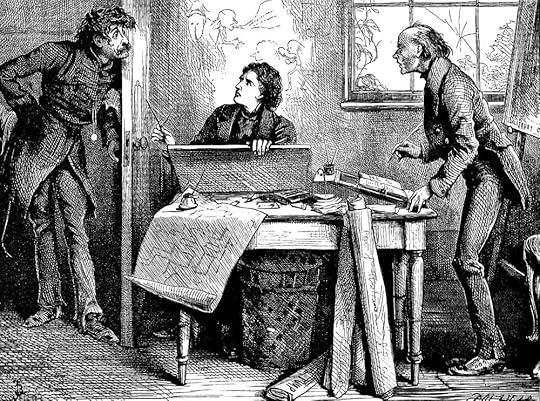

Montague Tigg and Chevy Slyme

Chapter 7

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

1867

Commentary:

In this fourth full-page dual character study for the novel, Eytinge characterises the parasitical Tigg and his "protégé" in the art of swindling and making loans that the pair will never repay, the Chuzzlewit cousin with the strong sense of entitlement, the euphoniously-named Chevy Slyme.

In Phiz's "Pleasant Little Family Party at Pecksniff's" the Chuzzlewit cousin Chevy Slyme is lost in the crowd of hangers-on surrounding the "bad eminence" (in Miltonic terms) of Seth Pecksniff — the smooth-tongued Montague Tigg and his protégé, the morose Chevy Slyme, being the figures immediately to Pecksniff's right.

In contrast, Eytinge makes a point of studying the two confidence men in isolation (even though in the text Tom Pinch and young Martin are in fact present) at a table in the Blue Dragon, where Mark Tapley has detained them over the non-payment of their bill. Whereas Phiz introduces them in the social context of the gathering of the Chuzzlewit clan at Pecksniff's, Eytinge finds a more self-revealing moment for the pair of parasites. Here is the point in the text at which Dickens and Eytinge introduce the small-time chiselers, the sour Chuzzlewit scion and his sweet-tempered, charming rogue of a companion and keeper (whose image Eytinge has clearly adapted from Phiz):

He was brooding over the remains of yesterday's decanter of brandy, and was engaged in the thoughtful occupation of making a chain of rings on the top of the table with the wet foot of his drinking-glass. Wretched and forlorn as he looked, Mr. Slyme had once been in his way, the choicest of swaggerers; putting forth his pretensions boldly, as a man of infinite taste and most undoubted promise. The stock in trade requisite to set up an amateur in this department of business is very slight, and easily got together; a trick of the nose and a curl of the lip sufficient to compound a tolerable sneer, being ample provision for any exigency. But, in an evil hour, this off-shoot of the Chuzzlewit trunk, being lazy, and ill qualified for any regular pursuit and having dissipated such means as he ever possessed, had formally established himself as a professor of Taste for a livelihood; and finding, too late, that something more than his old amount of qualifications was necessary to sustain him in this calling, had quickly fallen to his present level, where he retained nothing of his old self but his boastfulness and his bile, and seemed to have no existence separate or apart from his friend Tigg. And now so abject and so pitiful was he — at once so maudlin, insolent, beggarly, and proud — that even his friend and parasite, standing erect beside him, swelled into a Man by contrast.

"Chiv," said Mr Tigg, clapping him on the back, "my friend Pecksniff not being at home, I have arranged our trifling piece of business with Mr. Pinch and friend. Mr. Pinch and friend, Mr. Chevy Slyme! Chiv, Mr. Pinch and friend!"

"These are agreeable circumstances in which to be introduced to strangers," said Chevy Slyme, turning his bloodshot eyes towards Tom Pinch. "I am the most miserable man in the world, I believe!"

Tom begged he wouldn't mention it; and finding him in this condition, retired, after an awkward pause, followed by Martin. But Mr. Tigg so urgently conjured them, by coughs and signs, to remain in the shadow of the door, that they stopped there.

"I swear," cried Mr. Slyme, giving the table an imbecile blow with his fist, and then feebly leaning his head upon his hand, while some drunken drops oozed from his eyes, "that I am the wretchedest creature on record. Society is in a conspiracy against me. I'm the most literary man alive. I'm full of scholarship. I'm full of genius; I'm full of information; I'm full of novel views on every subject; yet look at my condition! I'm at this moment obliged to two strangers for a tavern bill!" [Chapter 7; Diamond Edition]

While the pessimistic, self-loathing Slyme stares into his brandy glass (not, as in the text, the decanter) and sees nothing but self-degradation and lost opportunities, the ever-optimistic Tigg looks up, as if already formulating his next scheme. His height, erect posture, extravagant Van Dyke, and military-looking surtout all suggest his theatrical, flamboyance and eloquence. Tigg is a survivor who knows how to manipulate and profit from his surly companion's Chuzzlewit connections.

"My name is Tigg how do you do?"

Chapter 7

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

They were both very busy on the afternoon succeeding the family’s departure—Martin with the grammar-school, and Tom in balancing certain receipts of rents, and deducting Mr Pecksniff’s commission from the same; in which abstruse employment he was much distracted by a habit his new friend had of whistling aloud while he was drawing—when they were not a little startled by the unexpected obtrusion into that sanctuary of genius, of a human head which, although a shaggy and somewhat alarming head in appearance, smiled affably upon them from the doorway, in a manner that was at once waggish, conciliatory, and expressive of approbation.

‘I am not industrious myself, gents both,’ said the head, ‘but I know how to appreciate that quality in others. I wish I may turn grey and ugly, if it isn’t in my opinion, next to genius, one of the very charmingest qualities of the human mind. Upon my soul, I am grateful to my friend Pecksniff for helping me to the contemplation of such a delicious picture as you present. You remind me of Whittington, afterwards thrice Lord Mayor of London. I give you my unsullied word of honor, that you very strongly remind me of that historical character. You are a pair of Whittingtons, gents, without the cat; which is a most agreeable and blessed exception to me, for I am not attached to the feline species. My name is Tigg; how do you do?’

Martin looked to Mr Pinch for an explanation; and Tom, who had never in his life set eyes on Mr Tigg before, looked to that gentleman himself.

"Oh, Chiv, Chiv,' murmured Mr. Tigg. 'You have a nobly independent nature, Chiv.'"

Chapter 7

Fred Barnard

Recalling Iago's blostering the sagging spirits of Roderigo in Shakespeare's The Tragedy of Othello, The Moor of Venice, Montague Tigg attempts to rally the despondent Chevy Slyme, who has lost his hopes amidst so numerous a contingent of possible Chuzzlewit heirs.

Text Illustrated:

‘Obliged to two strangers for a tavern bill, eh!’ repeated Mr Slyme, after a sulky application to his glass. ‘Very pretty! And crowds of impostors, the while, becoming famous; men who are no more on a level with me than—Tigg, I take you to witness that I am the most persecuted hound on the face of the earth.’

With a whine, not unlike the cry of the animal he named, in its lowest state of humiliation, he raised his glass to his mouth again. He found some encouragement in it; for when he set it down he laughed scornfully. Upon that Mr Tigg gesticulated to the visitors once more, and with great expression, implying that now the time was come when they would see Chiv in his greatness.

‘Ha, ha, ha,’ laughed Mr Slyme. ‘Obliged to two strangers for a tavern bill! Yet I think I’ve a rich uncle, Tigg, who could buy up the uncles of fifty strangers! Have I, or have I not? I come of a good family, I believe! Do I, or do I not? I’m not a man of common capacity or accomplishments, I think! Am I, or am I not?’

‘You are the American aloe of the human race, my dear Chiv,’ said Mr Tigg, ‘which only blooms once in a hundred years!’

‘Ha, ha, ha!’ laughed Mr Slyme again. ‘Obliged to two strangers for a tavern bill! I obliged to two architect’s apprentices. Fellows who measure earth with iron chains, and build houses like bricklayers. Give me the names of those two apprentices. How dare they oblige me!’

Mr Tigg was quite lost in admiration of this noble trait in his friend’s character; as he made known to Mr Pinch in a neat little ballet of action, spontaneously invented for the purpose.

‘I’ll let ‘em know, and I’ll let all men know,’ cried Chevy Slyme, ‘that I’m none of the mean, grovelling, tame characters they meet with commonly. I have an independent spirit. I have a heart that swells in my bosom. I have a soul that rises superior to base considerations.’

‘Oh Chiv, Chiv,’ murmured Mr Tigg, ‘you have a nobly independent nature, Chiv!’

‘You go and do your duty, sir,’ said Mr Slyme, angrily, ‘and borrow money for travelling expenses; and whoever you borrow it of, let ‘em know that I possess a haughty spirit, and a proud spirit, and have infernally finely-touched chords in my nature, which won’t brook patronage. Do you hear? Tell ‘em I hate ‘em, and that that’s the way I preserve my self-respect; and tell ‘em that no man ever respected himself more than I do!’

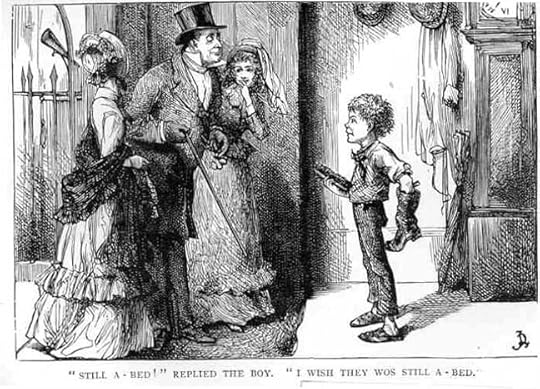

"Still-a-bed!" replied the boy. "I wish they wos still a-bed"\

Chapter 8

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

Mr Pecksniff looked about him for a moment, and then knocked at the door of a very dingy edifice, even among the choice collection of dingy edifices at hand; on the front of which was a little oval board like a tea-tray, with this inscription—‘Commercial Boarding-House: M. Todgers.’