Classics and the Western Canon discussion

This topic is about

Beyond Good and Evil

Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil

>

Preface and Part One

Lia wrote: "Anyway, I read this as questioning whether Socrates deserved capital punishment (for corrupting the youthful Plato, I suppose.) So Plato-the-beautiful-vegetable is blameless, one way or another. Socrates is the one on trial..."

Lia wrote: "Anyway, I read this as questioning whether Socrates deserved capital punishment (for corrupting the youthful Plato, I suppose.) So Plato-the-beautiful-vegetable is blameless, one way or another. Socrates is the one on trial..."I thought Nietzsche was being completely disingenuous about Socrates. It's like Chris said before in the analogy of astrology--it was a useful stage; it built the pyramids. Plato's 'malady' or sickness was something that "produced in Europe a magnificent tension of soul, such as had not existed anywhere previously." Nietzsche is saying (the way I read it), that modern (his modern) Europe is standing on the shoulders of giants--Plato, specifically, and by mustering the strength to overcome Platonized Christianity, Nietzsche's Europe has the ability to go beyond Plato, finally.

Thanks everyone for finding the reference in context.

Thanks everyone for finding the reference in context.I thought Pflanze (f.) was "plant," and "growth" is more literal for "Gewaechse,"- literally, "something which has grown."

"Product" I was going to mock, only to find my beloved Mrs. Zimmern has also used "product." It may be related to "produce," as in the produce section of the grocery store.

Bryan wrote: “ I thought Nietzsche was being completely disingenuous about Socrates. It's like Chris said before in the analogy of astrology--it was a useful stage; it built the pyramids. Plato's 'malady' or sickness was something that "produced in Europe a magnificent tension of soul, such as had not existed anywhere previously." Nietzsche is saying (the way I read it), that modern (his modern) Europe is standing on the shoulders of giants--Plato, specifically, and by mustering the strength to overcome Platonized Christianity, Nietzsche's Europe has the ability to go beyond Plato, finally. ”

Bryan wrote: “ I thought Nietzsche was being completely disingenuous about Socrates. It's like Chris said before in the analogy of astrology--it was a useful stage; it built the pyramids. Plato's 'malady' or sickness was something that "produced in Europe a magnificent tension of soul, such as had not existed anywhere previously." Nietzsche is saying (the way I read it), that modern (his modern) Europe is standing on the shoulders of giants--Plato, specifically, and by mustering the strength to overcome Platonized Christianity, Nietzsche's Europe has the ability to go beyond Plato, finally. ”I’m not even going to pretend I have any coherent idea about what Nietzsche meant to convey with his (rhetorical?) question regarding Socrates here. With that said, I suspect, Nietzsche might not be talking about a historical Socrates, he might be talking about a fictitious character that Plato invented. I mean Socrates most likely existed, but the one NIetzsche likes to insult is probably the product of Plato’s imagination.

But keep in mind what Nietzsche is saying in this section — philosophers philosophize under the influence of their prejudices. Plato might write something because he thinks it is true; or he might write something because he has some kind of vision he cherishes, and he is willing to craft “noble lies” to manipulate people into accepting his taste, his value, his judgments.

I hope you’re as confused as I am by now, I don’t think I can stuff more resentment into my person! But it sounds like Nietzsche is both in love with and extremely hostile to Plato, or his philosophy. He wants to draw him closer, and yet he wants to push him away. As though he’s playing Plato like a bow...

I wonder if the vegetative Plato is an allusion to Nietzsche’s own trees metaphor in the Gay Science. The one that talks about growing both upwards and downwards, both aspiring for what’s up there but also firmly reaches below to grip the earth, ever deeper...

I wonder if the vegetative Plato is an allusion to Nietzsche’s own trees metaphor in the Gay Science. The one that talks about growing both upwards and downwards, both aspiring for what’s up there but also firmly reaches below to grip the earth, ever deeper...Of course I have the Plato/ Aristotle pointing above/below image in my head when I make that association. If Nietzsche in fact calls Plato a plant, then maybe Nietzsche’s interpretation of Plato isn’t so idealistic?

He also invokes "the charm of the Platonic way of thinking, which was a noble way of thinking" in section 14, where he pits Plato against the sensual plebianism of physicists and Darwinists. Plato may have his faults, but the "old philologist" still has a soft spot for him.

He also invokes "the charm of the Platonic way of thinking, which was a noble way of thinking" in section 14, where he pits Plato against the sensual plebianism of physicists and Darwinists. Plato may have his faults, but the "old philologist" still has a soft spot for him.

Lia wrote: "If Nietzsche in fact calls Plato a plant, then maybe Nietzsche’s interpretation of Plato isn’t so idealistic?"

Lia wrote: "If Nietzsche in fact calls Plato a plant, then maybe Nietzsche’s interpretation of Plato isn’t so idealistic?"Regardless of Plato's taxonomic rank, I think the take-a-ways here are that Plato is a respected philosopher, but even he erred in his "inventions" of the purely spiritual and the "good as such" which are made all the more grievous and disease-like for their power and their ability to hang on so long. I would even dare to say If Nietzsche were still around today, he might refer to these errors as successful memes.

Lia wrote: "I’m not even going to pretend I have any coherent idea about what Nietzsche meant to convey with his (rhetorical?) question regarding Socrates here..."

Lia wrote: "I’m not even going to pretend I have any coherent idea about what Nietzsche meant to convey with his (rhetorical?) question regarding Socrates here..."I hope I don't sound as if I know--it's just what it sounded like to me.

In section 5 Nietzsche says he is more interested in the life-preserving properties of an opinion than in its truth. Should we say that this is Nietzsche's prejudice? It's a strange one for a philosopher.

In section 5 Nietzsche says he is more interested in the life-preserving properties of an opinion than in its truth. Should we say that this is Nietzsche's prejudice? It's a strange one for a philosopher.

Ahem. I just noticed this (because I can’t Latin and I didn’t check the endnotes...)

Ahem. I just noticed this (because I can’t Latin and I didn’t check the endnotes...) Thomas wrote: “

”

” Nietzsche wrote: “In every philosophy there is a point at which the philosopher's ‘conviction’ appears on the scene: or, to put it in the words of an ancient Mystery:

adventavit asinus,

pulcher et fortissimus.”

[“the ass came along,

beautiful and strong.”]

🤔

This whole thing is a satyr play, isn’t it? This group discussion, our moderator, BGE itself, this whole thing... is a joke!

Roger wrote: "In section 5 Nietzsche says he is more interested in the life-preserving properties of an opinion than in its truth. Should we say that this is Nietzsche's prejudice? It's a strange one for a philo..."

Roger wrote: "In section 5 Nietzsche says he is more interested in the life-preserving properties of an opinion than in its truth. Should we say that this is Nietzsche's prejudice? It's a strange one for a philo..."I was trying to figure this out when I ran into “the beautiful ass” above. (That’s in §8 BTW.)

I browsed through the text, I think the passage you’re referring to is in §4. In §5, Nietzsche savagely mocks old-Kant and Spinoza (He sounds like Aristophanes in Satyr mode).

But, I’m so glad you said that, because §3-4 is incredibly puzzling. (I wrote down “WUT??” on my margin.) From §4:

The falseness of a judgment is for us not necessarily an objection to a judgment; in this respect our new language may sound strangest. The question is to what extent it is life-promoting, life-preserving, species-preserving, perhaps even species-cultivating. And we are fundamentally inclined to claim that the falsest judgments (which include the synthetic judgments a priori) are the most indispensable for us; that without accepting the fictions of logic, without measuring reality against the purely invented world of the unconditional and self-identical, without a constant falsification of the world by means of numbers, man could not live—that renouncing false judgments would mean renouncing life and a denial of life. To recognize untruth as a condition of life —that certainly means resisting accustomed value feelings in a dangerous way; and a philosophy that risks this would by that token alone place itself beyond good and evil.

I’m quoting the whole thing for clarity, because otherwise I’m going to sound like I’m insane.

I think, Nietzsche is stating as a matter of fact — it’s not a preference, it’s not mere opinion — we judge certain things to be false, and we must accept them (LOL WUT?? Isn’t judging something to be “false” inherently a rejection?) He’s stating this as some kind of truth-statement: To recognize untruth as a condition of life is what place itself beyond good and evil. This is completely non-sensical, and I believe this is what Nietzsche is asserting.

I may be just re-stating what you've said, but I read this as him saying that untruth is a condition of life, period. Most philosophies won't recognize this--but any philosophy that does will inherently resist normal value judgments. Since Good and Evil are value judgments, a philosophy such as he's describing here is already beyond them.

I may be just re-stating what you've said, but I read this as him saying that untruth is a condition of life, period. Most philosophies won't recognize this--but any philosophy that does will inherently resist normal value judgments. Since Good and Evil are value judgments, a philosophy such as he's describing here is already beyond them.The sticking point seems to be whether or not a person agrees with the idea that untruth is a condition of life. If one disagrees with that, then the reasoning falls apart. Again, just the way I'm reading this, it seems that Nietzsche is saying that mankind lives his life under a lot of illusions--that's how he survives and continues the race. That "we are fundamentally inclined to claim that the falsest judgments...are the most indispensable for us; that without accepting the fictions of logic, without measuring reality against the purely invented world of the unconditional and self-identical, without a constant falsification of the world by means of numbers, man could not live."

I tend to think people as a general rule do live this way. We pick out a comfortable illusion and stick with it. Camus seemed to be someone who tried hardest to live without illusions and he had a devil of a time defending life against suicide.

In this case, I think it’s important to read §3 and §4 together. From §3:

In this case, I think it’s important to read §3 and §4 together. From §3:Behind all logic and its seeming sovereignty of movement, too, there stand valuations or, more clearly, physiological demands for the preservation of a certain type of life. For example, that the definite should be worth more than the indefinite, and mere appearance worth less than “truth”—such estimates might be, in spite of their regulative importance for us, nevertheless mere foreground estimates, a certain kind of niaiserie which may be necessary for the preservation of just such beings as we are. Supposing, that is, that not just man is the “measure of things —”

So Nietzsche is negating logic. To confirm that, from §4: ”...without accepting the fictions of logic, without measuring reality against the purely invented world of the unconditional and self-identical, without a constant falsification of the world by means of numbers, man could not live—that renouncing false judgments would mean renouncing life and a denial of life.”

Yep, it’s not [subjective] value he’s calling false, it is logic, something as rudimentary as self-identical assertions (i.e. A=A), that he’s calling “fiction,” “false.” That’s a little counter-intuitive, but that’s fine, we’re used to philosophers arguing completely nutty positions. My head-scratching here isn’t even about that, but the doubling down: not only is logic, self-identical, math, numbers etc mere fictions, we (as in Nietzsche) judge them to be false, and yet “falseness of a judgment is for us not necessarily an objection” — it’s false, and we accept them!

WAHHH.

Oh, BTW, I think that’s our mutual friend, Protagoras he’s [maybe] negating up there. (“Not juts man is the measure of things...”)

Oh, BTW, I think that’s our mutual friend, Protagoras he’s [maybe] negating up there. (“Not juts man is the measure of things...”)

Lia wrote: " (quoting Nietzsche)...For example, that the definite should be worth more than the indefinite, and mere appearance worth less than “truth”—such estimates might be, in spite of their regulative importance for us, nevertheless mere foreground estimates, a certain kind of niaiserie which may be necessary for the preservation of just such beings as we are. ..."

Lia wrote: " (quoting Nietzsche)...For example, that the definite should be worth more than the indefinite, and mere appearance worth less than “truth”—such estimates might be, in spite of their regulative importance for us, nevertheless mere foreground estimates, a certain kind of niaiserie which may be necessary for the preservation of just such beings as we are. ..."

He will get into it later- Descartes' decision to "doubt everything," and the one undeniable fact- "cogito." "I think." Well, did you really doubt everything, and is the "I think" the one undeniable fact you discovered while you were doubting everything?

Or are there a host of axioms behind the assertion "I think."?

Christopher wrote: "He will get into it later- Descartes' decision to "doubt everything," and the one undeniable fact- "cogito." "I think." Well, did you really doubt everything, and is the "I think" the one undeniable fact you discovered while you were doubting everything?..."

Christopher wrote: "He will get into it later- Descartes' decision to "doubt everything," and the one undeniable fact- "cogito." "I think." Well, did you really doubt everything, and is the "I think" the one undeniable fact you discovered while you were doubting everything?..."Oh, is that why he insulted (someone) in French in §3? (“Niaiserie”)

I don’t see how Descartes positing the thinking-thing is related to Nietzsche’s puzzling charges of inversion of value of definite/finite, appearance/truth though. (I know he condescendingly talks about Descartes’ naive quest for “immediate certainty” in §16, and charged the logic of the subject-I with superstitions and falsitication in §17. I just don’t really see how this is what’s being mocked in §3-4.)

Lia wrote: "In this case, I think it’s important to read §3 and §4 together. From §3:

Lia wrote: "In this case, I think it’s important to read §3 and §4 together. From §3:Behind all logic and its seeming sovereignty of movement, too, there stand valuations or, more clearly, physiological dem..."

Yes, I think he is putting logic on trial here. Logic as it's constructed must begin with axiomatic thought (A=A). It seems to me that he's going to the very root of it and questioning it. Like Chris just said, aren't there a host of axioms behind the assertion 'I think'?

It seems to me he's saying that logic, as it is constructed is designed to meet the "physiological demands for the preservation of a certain type of life." That there are "valuations" behind all logic, i.e. value judgments, i.e. this is good, this is bad.

You could have faultless logic, but if you start with a faulty premise, you'll still end up in the wrong place, right? The sentence before your clip is "the greater part of the conscious thinking of a philosopher is secretly influenced by his instincts, and forced into definite channels." That seems to be the kind of logic he's talking about. Even earlier in the paragraph, he says that one has 'to learn anew'--in order to shrug off this instinctive kind of thinking.

I don't know if I'm reading this right or not, but it seems like the arguments support one another. I think he attacks axiomatic thinking as being infected with instinctual thought that is beholden more to value judgments than to any actual truth. But that is necessary--it's critical, actually, because "the renunciation of false opinions would be a renunciation of life." Mankind, as a species, needs its illusions to continue. But any philosophy that recognized the presence of these illusions would be one that steps (or at least attempts to step) beyond the limits imposed by these value judgments--beyond Good and Evil, in other words.

Lia wrote: "Christopher wrote: "He will get into it later- Descartes' decision to "doubt everything," and the one undeniable fact- "cogito." "I think." Well, did you really doubt everything, and is the "I thin..."

Lia wrote: "Christopher wrote: "He will get into it later- Descartes' decision to "doubt everything," and the one undeniable fact- "cogito." "I think." Well, did you really doubt everything, and is the "I thin..."I think that Nietzsche is pointing out that we have muddled along quite nicely with a set of beliefs which he thinks are contrary to reality, and that we may NEED such beliefs to function at all.

{ADDENDUM: I couldn't find the "believe on instinct" passage in Nietzsche, because Kaufmann was instead quoting part of sentence by F.H. Bradley, a British Idealist: "Metaphysics is the finding of bad reasons for what we believe upon instinct; but to find these reasons is no less an instinct." I finally thought to Google-search for the passage without including Nietzsche's name in the search parameters.....}

He sometimes seems to regard the actual Truth as something too disturbing for most people to contemplate, so they have to be content with something else, which is "good enough" for their purposes. And philosophers join in with "finding bad reasons for what we are already determined to believe on instinct." (Sorry, I don't have the reference for that line: Kaufmann fails to note the source when he quotes it in his "Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist," and it doesn't show up in a search of "Basic Writings.")

In fact, he sometimes sounds like a character in H.P. Lovecraft, who meddles with "Things Man Was Not Meant to Know," and suffers the awful consequences. Of course, Nietzsche didn't have a pantheon of ancient godlike beings, and extra-terrestrial Things, all mostly indifferent to human beings, to dramatize the idea.

(Lovecraft seems to have read some Nietzsche, at one time or another, although he probably got the basic idea from previous supernatural horror fiction -- not to mention "Frankestein.")

Bryan wrote: "Lia wrote: "In this case, I think it’s important to read §3 and §4 together. From §3:

Bryan wrote: "Lia wrote: "In this case, I think it’s important to read §3 and §4 together. From §3:Behind all logic and its seeming sovereignty of movement, too, there stand valuations or, more clearly, physio..."

The way you put it is entirely unproblematic: logic itself (could be ) faultless, but logic is a mere subset of human activities, we also function under instincts, drives, etc. So let’s accept logic but let it be modified with something more irrational and subjective.

But he seems to be saying something else: logic itself is fiction, it’s false! Although it’s false, there’s nothing wrong with accepting it! Can you knowingly accept what you judge, know, understand to be false? Doesn’t saying “something is false” imply you reject it? If I think 1+1 ≠ 3, can I then say I accept 1+1 = 3?

Bryan wrote: "I tend to think people as a general rule do live this way. We pick out a comfortable illusion and stick with it. Camus seemed to be someone who tried hardest to live without illusions and he had a devil of a time defending life against suicide."

Bryan wrote: "I tend to think people as a general rule do live this way. We pick out a comfortable illusion and stick with it. Camus seemed to be someone who tried hardest to live without illusions and he had a devil of a time defending life against suicide."I think this is exactly what he's getting at. The reasons why most people believe the things they do have nothing to with truth, or logic, or the expert advice of those who actually know what they're talking about. Most people believe they are in the right because of the way they feel about things, regardless of logic or evidence. (Hence the advertising business.) But an acknowledgment of ignorance makes us uncomfortable, and it shakes our self-identity. We go with makes us feel comfortable, which is usually informed by our social units. Nietzsche paints this as weakness, but it is also "human, all too human."

The prejudice of philosophers is no different than this, if it is a kind of blind dogma. But once that dogma has been broken down -- if it can be broken down -- by cynicism or dialectic or what have you, what then? There must be a reason why humans take a stand on things, fallible as those stands may be. Surely Nietzsche doesn't expect us to simply wander in cynical darkness, reflecting only on our imperfections?

Ian wrote: "In fact, he sometimes sounds like a character in H.P. Lovecraft, who meddles with "Things Man Was Not Meant to Know," and suffers the awful consequences. Of course, Nietzsche didn't have a pantheon of ancient godlike beings, and extra-terrestrial Things, all mostly indifferent to human beings, to dramatize the idea..."

Ian wrote: "In fact, he sometimes sounds like a character in H.P. Lovecraft, who meddles with "Things Man Was Not Meant to Know," and suffers the awful consequences. Of course, Nietzsche didn't have a pantheon of ancient godlike beings, and extra-terrestrial Things, all mostly indifferent to human beings, to dramatize the idea..."Like our old friend Oedipus, for example :D

Oh crap, I think we’ve been warned. Do we really want to overcome Nietzsche-the-sphinx’s riddles? Are we ready for “the Truth” TM?

Lia wrote: "Can you knowingly accept what you judged, know, understand to be false? Doesn’t saying something is false imply you reject it? If I think 1+1 ≠ 3, can I then say I accept 1+1 = 3? ..."

Lia wrote: "Can you knowingly accept what you judged, know, understand to be false? Doesn’t saying something is false imply you reject it? If I think 1+1 ≠ 3, can I then say I accept 1+1 = 3? ..."I don't know if I can or not. I think that's what Nietzsche is asking us to do when he says 'one has here to learn anew'.

Actually, I do know if I can accept what's false--I think I do it all the time. I think there are hundreds if not thousands of polite fictions I accept to be a member of society, even though I don't believe them to be true, or even to actually be necessary, but they are more convenient. I think there are many fictions I adhere to in my thoughts about the future and what it holds that have no actual basis in fact--maybe not even in probability. But without those fictions I would be paralyzed by doubt, fear, and uncertainty.

Bryan wrote: "I can accept what's false--I think I do it all the time. I think there are hundreds if not thousands of polite fictions I accept to be a member of society, even though I don't believe them to be true, or even to actually be necessary, but they are more convenient. I think there are many fictions I adhere to in my thoughts about the future and what it holds that have no actual basis in fact ”

Bryan wrote: "I can accept what's false--I think I do it all the time. I think there are hundreds if not thousands of polite fictions I accept to be a member of society, even though I don't believe them to be true, or even to actually be necessary, but they are more convenient. I think there are many fictions I adhere to in my thoughts about the future and what it holds that have no actual basis in fact ” Like going to church for social reasons rather than actual faith, or buying milk with happy cows in a pastoral scene picture when I know the cow probably suffered in a factory farm. Or treating corporations as though they were actual humans with legal rights.

Somehow I don't think that's what Nietzsche is talking about. It's not that we fail to be perfect Homo economicus, but rather, reason itself is fiction, A!=A, the believe in reason itself is precisely madness...And we must continue to accept that.

Lia wrote: "Somehow I don't think that's what Nietzsche is talking about...."

Lia wrote: "Somehow I don't think that's what Nietzsche is talking about...."I thought you might say that. :)

I'll concede the point, although I think what I'm talking about is symptomatic of the more specific point that he's making.

But I do think that he is challenging reason and argument, as they have been presented to us throughout our history by these older philosophers.

I don't want to misread your posts: If I am reading them correctly, you resist the idea of accepting what we believe are false propositions. (If I'm not saying it right, tell me--I don't want to put words in your mouth)

My interpretation is that he is saying all instinctual thought is tinged with subjectivity, and therefore all (not just bearded philosophers) reasoning is open to being false right from the get go. So our belief that 1+1 ≠ 3 has no firm ground to stand on in the first place, other than our faith in it.

I had forgotten (until I was reminded by reading Kaufmann) that there is a whole book by one Hans Vaihinger on the subject of treating or regarding things "as if" they were true or real, "Die Philosophie des Als Ob: System der theoretischen, praktischen und religiösen Fiktionen der Menschheit auf Grund eines idealistischen Positivismus" (1911), translated in 1925 as The Philosophy of "As If": A System of the Theoretical, Practical and Religious Fictions of Mankind which has been translated, and is even available in an inexpensive Kindle edition. (Which I have, but I had not remembered the Nietzsche connection).

I had forgotten (until I was reminded by reading Kaufmann) that there is a whole book by one Hans Vaihinger on the subject of treating or regarding things "as if" they were true or real, "Die Philosophie des Als Ob: System der theoretischen, praktischen und religiösen Fiktionen der Menschheit auf Grund eines idealistischen Positivismus" (1911), translated in 1925 as The Philosophy of "As If": A System of the Theoretical, Practical and Religious Fictions of Mankind which has been translated, and is even available in an inexpensive Kindle edition. (Which I have, but I had not remembered the Nietzsche connection).The last section of the fairly long book (Amazon says 315 or 420 pages, depending on the edition) is on "Nietzsche and His Doctrine of Conscious Illusion," as one of Vaihinger's historical examples. (Vaihinger should have been familiar with his writings, having written "Nietzsche als Philosoph" [1902], but that isn't always a guarantee. Kaufmann was unenthusiastic about the earlier book.)

The Kindle edition was scanned from the 1925 edition, but has been reformatted, and the "Editor's Note" claims that it was carefully proofread. At the same time the spelling was also Americanized, and some errors ("textual and referential") corrected.

So far as I have been able to tell, the formatting is excellent. I haven't sat down to read the whole thing, although it is on my TBR list. I tried reading it in High School, but a lot of it seemed opaque -- perhaps not enough background on my part. I'm interested to see if anything has changed.

I don't know if I'm resisting it, so much as I'm upset that nobody else finds this scandalous! (Or funny because absurd at the very least.)

I don't know if I'm resisting it, so much as I'm upset that nobody else finds this scandalous! (Or funny because absurd at the very least.)He's not saying we humans don't live according to logic, he's saying logic is false, and we don't have to reject falsehood. In a way it makes sense: if logic is fiction then anything goes, to say something is false no longer implies rejection. This is like Joycean Nighttown where none of the rules apply (or Alice in wonderland ...)

I'm a bit hung up on this, because I think this has implications for how we parse the rest of the text.

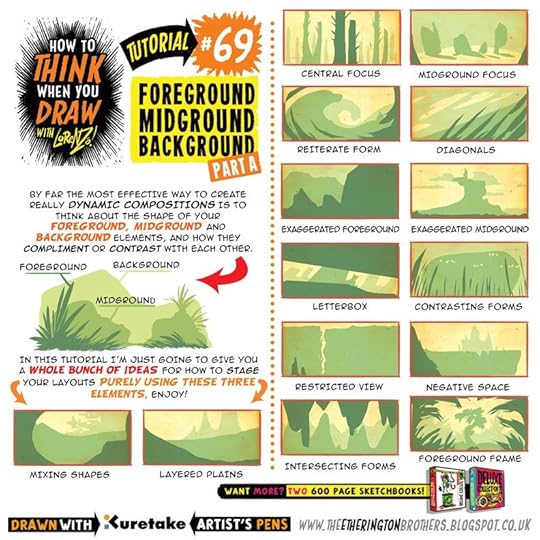

What I was trying to point out, but not spelling out, was that Nietzsche takes the philosophers' emphasis on logic, and compares it to an artist doing a 'foreground estimate.' (Google this to find out how important it is in robotics, or AI, or I don't know what)-

What I was trying to point out, but not spelling out, was that Nietzsche takes the philosophers' emphasis on logic, and compares it to an artist doing a 'foreground estimate.' (Google this to find out how important it is in robotics, or AI, or I don't know what)-What he is getting at, or one thing he is getting at, is the perspectivism, so to speak, of philosophy. Hitherto, they have worn a mask, or deceived themselves (I would go with the mask theory myself) that they were discovering 'the truth,' when, consciously or unconsciously, they were 'creating values.'

Like an artist- in order (no pun intended) to paint what's there, he has to impose an artistic order on what he sees. Even the simplest picture does this:

So, your quote:

without accepting the fictions of logic, without measuring reality against the purely invented world of the unconditional and self-identical, without a constant falsification of the world by means of numbers, man could not live—that renouncing false judgments would mean renouncing life and a denial of life.

-Does sort of lead to Husserl and Heidegger- the 'phenomenology' which says that there is a lot of atavism underlying the 'purest' logic.

Incidentally, I encountered something today which seemed positively Nietzschean, In The Fatal Conceit: The Errors of Socialism:

Mind Is Not a Guide but a Product of Cultural Evolution, and Is Based More on Imitation than on Insight or Reason

We have mentioned the capacity to learn by imitation as one of the prime benefits conferred during our long instinctual development. Indeed, perhaps the most important capacity with which the human individual is genetically endowed, beyond innate responses, is his ability to acquire skills by largely imitative learning. In view of this, it is important to avoid, right from the start, a notion that stems from what I call the ‘fatal conceit’: the idea that the ability to acquire skills stems from reason. For it is the other way around: our reason is as much the result of an evolutionary selection process as is our morality.

And Hayek and Nietzsche may have seen the same 'fatal conceit' from the same quarter, politically.

Lia wrote: "Somehow I don't think that's what Nietzsche is talking about. It's not that we fail to be perfect Homo economicus, but rather, reason itself is fiction, A!=A, the believe in reason itself is precisely madness...And we must continue to accept that."

Lia wrote: "Somehow I don't think that's what Nietzsche is talking about. It's not that we fail to be perfect Homo economicus, but rather, reason itself is fiction, A!=A, the believe in reason itself is precisely madness...And we must continue to accept that."I think he's saying that philosophers use logic disingenuously, not that logic is fiction. In short, philosophers suffer from confirmation bias -- they argue a case, but they argue from a position borne of self interest. Their arguments can't defy logic or they would be unpersuasive, but they can and do start with premises with an aim to a specific conclusion. They emphasize certain pieces of evidence and diminish others, all in an effort to reach the conclusion they desire. Nietzsche's claim is that what is behind the logic, instinct and self-preservation, is in these cases prior to the logic itself, because self-preservation is the goal. Logic is just a rhetorical tool.

Thomas wrote: "I think he's saying that philosophers use logic disingenuously, not that logic is fiction..."

Thomas wrote: "I think he's saying that philosophers use logic disingenuously, not that logic is fiction..."Isn't he?

And we are fundamentally inclined to claim that the falsest judgments (which include the synthetic judgments a priori) are the most indispensable for us; that without accepting the fictions of logic, without measuring reality against the purely invented world of the unconditional and self-identical, without a constant falsification of the world by means of numbers, man could not live

It sounds like he's saying they are not just false amongst other false judgments we routinely make, but the a priori, the fictions of logic, the purely invented word of unconditional self-identical, the falsification with numbers.. are in themselves the falsest! (Who knew falsehood comes in degree?)

He may be denying there is any such thing as a synthetic a ptioti judgement.

He may be denying there is any such thing as a synthetic a ptioti judgement.Going back to Hume.

Or consider the "form" of a circle.

No existing circle has the properties of an abstract, perfect circle.

No actual line extends to infinity, yet synthetically and a priori, we know that two parallel lines extended to infinity would never meet.

I think what Nietzsche is calling 'false' here is the inference that the actual sub-lunar world is imperfect, and that there is a truer, ideal world with which we can compare it.

I think he's commenting on the phenomenon, which for him is a kind of sophistry. I don't think he's arguing for it. The phenomenon is that logic is misused for self-serving reasons, not that logic is fictional. Lying with statistics does not invalidate statistics as a science, for example. And never ask Lobachevsky for directions anywhere.

I think he's commenting on the phenomenon, which for him is a kind of sophistry. I don't think he's arguing for it. The phenomenon is that logic is misused for self-serving reasons, not that logic is fictional. Lying with statistics does not invalidate statistics as a science, for example. And never ask Lobachevsky for directions anywhere.

Yes, it seems N. was very "up" on what must have been very new physics at the time- that the "atom" was not solid.

Yes, it seems N. was very "up" on what must have been very new physics at the time- that the "atom" was not solid.

I'm not sure--I think he could be arguing against logic. Is there a logical system that could be developed without an underlying axiomatic structure? Either N is thinking that we still haven't gotten axiomatic enough, or else that there can be no logic conceived that isn't warped in some way by the logician.

I'm not sure--I think he could be arguing against logic. Is there a logical system that could be developed without an underlying axiomatic structure? Either N is thinking that we still haven't gotten axiomatic enough, or else that there can be no logic conceived that isn't warped in some way by the logician. The logical process is fine, but as human beings we are incapable of starting without a faulty premise. So we have to push past logic with all its inherent value judgments.

He hasn't really talked about how we would do that though, at least not in this chapter.

Look, that donkey over there is laughing! I think he's amused that we each interpret the same passage differently, depending on what we find acceptable ... or reasonable?

Look, that donkey over there is laughing! I think he's amused that we each interpret the same passage differently, depending on what we find acceptable ... or reasonable?

How about . . .

How about . . .That donkey must be Nietzsche, because you're each doing what he says philosophers do. There is no truth, but there is meaning, and each of you has sought out the meaning that works best for you based on a lifetime of acquired assumptions and prejudices you bring to the reading. He would say this of all of us.

Let me try one more time on the falseness of logic:

Let me try one more time on the falseness of logic:https://io9.gizmodo.com/5715101/all-t...

"All the greatest scenes where someone talks a computer into self-destructing."

(Staring with a mash-up of the three times Kirk did it).

I'm still basking in the glorious fact that I managed to call Nietzsche an ass inadvertently.

I'm still basking in the glorious fact that I managed to call Nietzsche an ass inadvertently. Any idea or theory what Section 8 is about, BTW? Why is the donkey on stage?

Lia wrote: "I'm still basking in the glorious fact that I managed to call Nietzsche an ass inadvertently.

Lia wrote: "I'm still basking in the glorious fact that I managed to call Nietzsche an ass inadvertently. Any idea or theory what Section 8 is about, BTW? Why is the donkey on stage?"

One kind of wishes Kaufmann had elaborated on this, but of course HE didn't have Wikipedia:

Once detached from the parent stem, the Festum Asinorum branched in various directions. In the Beauvais 13th century document the Feast of Asses is already an independent trope with the date and purpose of its celebration changed.[4]

At Beauvais the Ass may have continued his minor role of enlivening the long procession of Prophets. On the January 14, however, he discharged an important function in that city's festivities. On the feast of the Flight into Egypt the most beautiful girl in the town, with a pretty child in her arms, was placed on a richly draped ass, and conducted with religious gravity to St Stephen's Church. The Ass (possibly a wooden figure) was stationed at the right of the altar, and the Mass was begun. After the Introit a Latin prose was sung.[4]

The first stanza and its French refrain may serve as a specimen of the nine that follow:

Orientis partibus

Adventavit Asinus

Pulcher et fortissimus

Sarcinis aptissimus.

Hez, Sire Asnes, car chantez,

Belle bouche rechignez,

Vous aurez du foin assez

Et de l'avoine a plantez.

(From the Eastern lands the Ass is come, beautiful and very brave, well fitted to bear burdens. Up! Sir Ass, and sing. Open your pretty mouth. Hay will be yours in plenty, and oats in abundance.)

Mass was continued, and at its end, apparently without awakening the least consciousness of its impropriety, the following direction (in Latin) was observed:

In fine Missae sacerdos, versus ad populum, vice 'Ite, Missa est', ter hinhannabit: populus vero, vice 'Deo Gratias', ter respondebit, 'Hinham, hinham, hinham.'

(At the end of Mass, the priest, having turned to the people, in lieu of saying the 'Ite missa est', will bray thrice; the people instead of replying 'Deo Gratias' say, 'Hinham, hinham, hinham.')

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feast_o...

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "How about . . .

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "How about . . .That donkey must be Nietzsche, because you're each doing what he says philosophers do. There is no truth, but there is meaning, and each of you has sought out the meaning that work..."

Nice observation, Xan. I would like to think that my interpretation of this chapter is an attempt to honestly understand what Nietzsche has written here, but I also know that this interpretation is informed by everything else I have read and experienced. But this is the case with Nietzsche as well, as he admits when he declares that the causa sui is "the best self-contradiction that has been conceived so far, it is a sort of rape and perversion of logic..." (21).

There are no "immediate certainties" for Nietzsche either. Instead there is a psychology, and ulterior motives, and whatever else he's going to come up with for ground support. It can't be turtles (or donkeys) all the way down.

Good thing we're not chasing girls here, because the donkey might die laughing at our attempts.

Good thing we're not chasing girls here, because the donkey might die laughing at our attempts. So, um, does "the correct interpretation" matter? Why not misinterpretation? Or uncertainty? What is the value of finding the singular, correct, ultimate, final, truthful interpretation? What is the value of this will? Who first raised the ridiculous question? (And, is "interpretation" a woman??)

Winner gets to take the donkey home!

Thomas wrote: "There are no "immediate certainties" for Nietzsche either. Instead there is a psychology, and ulterior motives, and whatever else he's going to come up with for ground support. "

Thomas wrote: "There are no "immediate certainties" for Nietzsche either. Instead there is a psychology, and ulterior motives, and whatever else he's going to come up with for ground support. "Is this how Nietzsche justifies "Will to Power?"

Here's what I'm wondering about Nietzsche. If there is no truth, no immediate certainties (and perhaps no certainties), then psychology becomes paramount and the Will to Power (a psychological state of mind) becomes truth or the way for the individual to create his own truth. An intriguing and dangerous proposition.

I also wonder if Nietzsche isn't being intentionally vague and metaphorical to force different interpretations, a way of getting us to unwittingly show ourselves what he means.

I don't buy this Will to Power. Sure, that's what some people want, but others want pleasure, or comfort, or love, or victory, or esteem. Some hunger and thirst after righteousness. Why give Power pride of place?

I don't buy this Will to Power. Sure, that's what some people want, but others want pleasure, or comfort, or love, or victory, or esteem. Some hunger and thirst after righteousness. Why give Power pride of place?

Yes, Ian, I can see it coming to that given N's view of truth and relativism. Intriguing and dangerous.

Yes, Ian, I can see it coming to that given N's view of truth and relativism. Intriguing and dangerous.

Christopher wrote: "Yes, it seems N. was very "up" on what must have been very new physics at the time- that the "atom" was not solid."

Christopher wrote: "Yes, it seems N. was very "up" on what must have been very new physics at the time- that the "atom" was not solid."This didn't involve "new physics" at all.

Buried in message #32 (on Kuhn's view of scientific revolutions) I made an observation on Nietzsche's rejection of the atomic theory of matter.

This was partly for philosophical reasons (going back to the eighteenth century), but it seems to have reflected an on-going dispute between chemists and physicists.

The former had long since accepted an atomic nature of matter, and with it the idea of molecules made up of them. But a lot of physicists regarded such solid, "billiard ball" atoms as mathematical figments, useful for calculations, but not representing reality -- rather like the use of Ptolemaic astronomy to calculate the naked-eye appearance of the heavens, without having any truth value in itself.

Many chemists were too busy successfully synthesizing new substances on the basis of the theory, not just predicting observations of natural processes, to take the theoretical objections very seriously.

I there referred, for a summary of the dispute, to the Wikipedia article on Ludwig Boltzmann, a physicist who, in the face of considerable professional opposition, showed that the atomic theory could be used in physics as well, and must have some kind of real foundation.

Of course, once the physicists got to work on the idea that the atom represented something real, they began investigating it for themselves, using their own techniques, and wound up demonstrating that, in a way, their predecessors had a point -- the chemists' irreducible atom wasn't the ultimate constituent of matter after all. The discovery of the electron came in 1897.

Roger wrote: "I don't buy this Will to Power. Sure, that's what some people want, but others want pleasure, or comfort, or love, or victory, or esteem. Some hunger and thirst after righteousness. Why give Power ..."

Roger wrote: "I don't buy this Will to Power. Sure, that's what some people want, but others want pleasure, or comfort, or love, or victory, or esteem. Some hunger and thirst after righteousness. Why give Power ..."Hi, Roger!

I think that is right, and I think N. would conclude they are not Ubermensch. They would be the rabble. There's a lot N. says I don't agree with. A question I have is why N doesn't think all this relativism leads to nihilism. Perhaps this "Will to Power" (or Ubermensch) is his escape pod.

Ian wrote: "The discovery of the electron came in 1897. ..."

Ian wrote: "The discovery of the electron came in 1897. ..."Ian, this is kind of my point. Nietzsche was alluding to sub-atomic theory, which must have been 'cutting edge.'

But, I was actually wrong. At any rate, N. says Boscovich was onto a theory that atoms, too, had a will to power:

In 1745 Bošković published De Viribus Vivis in which he tried to find a middle way between Isaac Newton's gravitational theory and Gottfried Leibniz's metaphysical theory of monad-points. He developed a concept of "impenetrability" as a property of hard bodies which explained their behaviour in terms of force rather than matter. Stripping atoms of their matter, impenetrability is disassociated from hardness and then put in an arbitrary relationship to elasticity. Impenetrability has a Cartesian sense that more than one point cannot occupy the same location at once.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roger_J...

Lia wrote: "I'm still basking in the glorious fact that I managed to call Nietzsche an ass inadvertently.

Lia wrote: "I'm still basking in the glorious fact that I managed to call Nietzsche an ass inadvertently. Any idea or theory what Section 8 is about, BTW? Why is the donkey on stage?"

My thoughts on this section are that he Is referring to the eventual point where the philosopher has to publicly live or die by his philosophy. Most just prove the philosophy they are metaphorically riding on is an ass.

I also thought that, the ass arriving most beautiful and most valiant in the old "mystery" play may also be an example of the above referencing Jesus' arrival Jerusalem on a donkey.

Books mentioned in this topic

Critique of Pure Reason (other topics)Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics (other topics)

The Philosophy of "As If": A System of the Theoretical, Practical and Religious Fictions of Mankind (other topics)

Thus Spoke Zarathustra (other topics)

Thus Spoke Zarathustra (other topics)

More...

Still, the lotus/ molis association is tantalizing. I think the bow/tension metaphor is central here, I suspect that’s what BGE is about, and obviously the bow tension metaphor went back to Plato... AND The Odyssey! If there are more allusions to / commentaries on Homer, i’ll be stoked!

Although, sickness/health and hemlock seem to make a fitting set as well.