The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

The Pickwick Papers

The Pickwick Papers

>

PP, Chp. 18-20

Chapter 19 is mainly based on slapstick, which is not to say that it is less interesting, and it might give us an idea of what Pickwick Papers could have looked like, had Dickens not finally had his own way with the storyline and the overall character of the novel.

The chapter begins with the following portentous words:

As in the case of the unoffending and unsuspicious partridges, our friends, too, start the day with high expectations and in blissful ignorance of what – thanks to Captain Boldwig – their leader will have to endure before the sun has set. As was foreshadowed in the previous chapter, Mr. Wardle and the Pickwickians are going bird-shooting on Sir Geoffrey Manning’s premises. This time, not only Mr. Winkle is supposed to take up arms against the partridges, but also Mr. Tupman. Mr. Snodgrass is not because he has preferred to stay at home. Since Mr. Pickwick is still suffering from rheumatism and cannot walk properly, it is decided, on a little boy’s suggestion, to transport him in a wheelbarrow in order to enable him – and Mr. Weller, who is to push the wheelbarrow – to take part in the proceedings. Albeit, Mr. Pickwick soon finds reason to regret his participation since he finds that both Mr. Winkle and Mr. Tupman have an unsettling way of carrying their guns so that he insists that both gentlemen carry them with their muzzles downwards. Mr. Wardle is thoroughly amused at the awkwardness Mr. Winkle displays, but the reader will probably be even more amused by the wry remarks the gamekeeper makes at the expense of the two gentlemen. Anyway, the gamekeeper in this chapter did outshine Sam Weller for me in terms of wit and glibness. For example, when Mr. Winkle inadvertently discharges his gun, nearly killing the gamekeeper, the man simply says,

Matters grow worse for Mr. Winkle, not only because he fails to shoot any birds, but still more so because Mr. Tupman, by mere chance, manages to bring down a capital bird, to Mr. Wardle’s admiration. Mr. Tupman is honest enough to protest that it was a mere lucky shot but, ironically, this protestation is regarded by Mr. Wardle as the modesty of a truly good shot, and hence, Mr. Tupman’s reputation is made.

Noon approaching, the friends, to the utmost delight of Mr. Weller, now start their picnic at a little hill, and Sam, on finding that there are veal pies, delights the company with an anecdote of a pieman, an acquaintance of his, who told him that piemen very often put cats into their pies but they are so expert at seasoning them that nobody can tell the difference from beef or veal. On the occasion of the picnic, or rather the unpacking of the victuals, Sam Weller uses the only two Wellerisms I could find in this chapter, and here they are:

1. “’Out of the vay, young leathers. If you walley my precious life, don’t upset me, as the gen’l’man said to the driver when they was a carryin’ him to Tyburn.’”

2. “’Now, gen’l’m’n, “fall on”, as the English said to the French when they fixed bagginets.’”

Mr. Weller seems to be in a very morbid mood on this outing because both his pieman’s story and the two Wellerisms are rather macabre.

As usual, our friends enjoy their vittles and their drink – beer and cold punch, this time –, and it can be noted that Mr. Pickwick especially liberally partakes of the latter. I’ll quote this passage because I really love the way the narrator puts it:

Also the effect of the punch on Mr. Pickwick is interesting to behold:

This brings me to a bunch – not a punch – of questions: Was it usual in the 1830s to indulge so freely in alcoholic beverages as Mr. Pickwick and his friends do? What might Dickens’s readers have thought about it at the time? And how does Dickens’s treatment of alcohol change – if it does – in the course of his writings? I have a feeling that in later novels, we see a lot more of the detrimental effects of too liberal a use of alcohol. Or is it just a question of class in Dickens – Mr. Pickwick is a well-to-do gentleman, whereas the drunkards in Hard Times, Bleak House and Our Mutual Friend are not.

Be that as it may, Mr. Pickwick having fallen asleep, our friends decide to leave him behind and finish the shooting bit of the day without him. He appears to be safe in his barrow for Mr. Wardle and the others, but it happens that the picnic took place no Sir Geoffrey’s neighbour’s grounds, and that this neighbour is an irascible and overweening man with the befitting title of Captain Boldwig, who will not have any trespassers on his property and even contemplates putting up spring guns [1]. Captain Boldwig is so annoyed by the view of the sleeping Mr. Pickwick, whom he considers to just feign being asleep, that he orders his gardener to wheel the man into the Pound, i.e. the pigsty, where Mr. Pickwick by and by recovers his senses, only to find himself surrounded by a crowd of gloaters who even throw vegetables at him.

It will probably not surprise us that as soon as his friends have got him out of that unenviable situation, Mr. Pickwick only briefly entertains the idea of having Captain Boldwig brought to justice for his treatment, because after all, as Mr. Wardle points out, they were trespassing – but that they all stop at a roadside tavern in order to … have some brandy-and-water to “keep up their good-humour”.

[1] According to a note in my Penguin issue, spring guns – i.e. hidden guns that could be triggered by a wire – were perfectly legal means of protecting your property from trespassers and, especially, poachers. They were made illegal, though, in 1827 by an Act of Parliament, which means that, the novel taking place around 1830, no longer is allowed to use them. But he does not seem to care.

The chapter begins with the following portentous words:

”The birds, who, happily for their own peace of mind and personal comfort, were in blissful ignorance of the preparations which had been making to astonish them, on the first of September, hailed it, no doubt, as one of the pleasantest mornings they had seen that season. Many a young partridge who strutted complacently among the stubble, with all the finicking coxcombry of youth, and many an older one who watched his levity out of his little round eye, with the contemptuous air of a bird of wisdom and experience, alike unconscious of their approaching doom, basked in the fresh morning air with lively and blithesome feelings, and a few hours afterwards were laid low upon the earth. But we grow affecting: let us proceed.”

As in the case of the unoffending and unsuspicious partridges, our friends, too, start the day with high expectations and in blissful ignorance of what – thanks to Captain Boldwig – their leader will have to endure before the sun has set. As was foreshadowed in the previous chapter, Mr. Wardle and the Pickwickians are going bird-shooting on Sir Geoffrey Manning’s premises. This time, not only Mr. Winkle is supposed to take up arms against the partridges, but also Mr. Tupman. Mr. Snodgrass is not because he has preferred to stay at home. Since Mr. Pickwick is still suffering from rheumatism and cannot walk properly, it is decided, on a little boy’s suggestion, to transport him in a wheelbarrow in order to enable him – and Mr. Weller, who is to push the wheelbarrow – to take part in the proceedings. Albeit, Mr. Pickwick soon finds reason to regret his participation since he finds that both Mr. Winkle and Mr. Tupman have an unsettling way of carrying their guns so that he insists that both gentlemen carry them with their muzzles downwards. Mr. Wardle is thoroughly amused at the awkwardness Mr. Winkle displays, but the reader will probably be even more amused by the wry remarks the gamekeeper makes at the expense of the two gentlemen. Anyway, the gamekeeper in this chapter did outshine Sam Weller for me in terms of wit and glibness. For example, when Mr. Winkle inadvertently discharges his gun, nearly killing the gamekeeper, the man simply says,

”’Never mind, Sir, never mind, […] I’ve no family myself, sir; and this here boy’s mother will get something handsome from Sir Geoffrey, if he’s killed on his land. Load again, Sir, load again.’”

Matters grow worse for Mr. Winkle, not only because he fails to shoot any birds, but still more so because Mr. Tupman, by mere chance, manages to bring down a capital bird, to Mr. Wardle’s admiration. Mr. Tupman is honest enough to protest that it was a mere lucky shot but, ironically, this protestation is regarded by Mr. Wardle as the modesty of a truly good shot, and hence, Mr. Tupman’s reputation is made.

Noon approaching, the friends, to the utmost delight of Mr. Weller, now start their picnic at a little hill, and Sam, on finding that there are veal pies, delights the company with an anecdote of a pieman, an acquaintance of his, who told him that piemen very often put cats into their pies but they are so expert at seasoning them that nobody can tell the difference from beef or veal. On the occasion of the picnic, or rather the unpacking of the victuals, Sam Weller uses the only two Wellerisms I could find in this chapter, and here they are:

1. “’Out of the vay, young leathers. If you walley my precious life, don’t upset me, as the gen’l’man said to the driver when they was a carryin’ him to Tyburn.’”

2. “’Now, gen’l’m’n, “fall on”, as the English said to the French when they fixed bagginets.’”

Mr. Weller seems to be in a very morbid mood on this outing because both his pieman’s story and the two Wellerisms are rather macabre.

As usual, our friends enjoy their vittles and their drink – beer and cold punch, this time –, and it can be noted that Mr. Pickwick especially liberally partakes of the latter. I’ll quote this passage because I really love the way the narrator puts it:

”‘With the greatest delight,’ replied Mr. Tupman; and having drank that glass, Mr. Pickwick took another, just to see whether there was any orange peel in the punch, because orange peel always disagreed with him; and finding that there was not, Mr. Pickwick took another glass to the health of their absent friend, and then felt himself imperatively called upon to propose another in honour of the punch-compounder, unknown.”

Also the effect of the punch on Mr. Pickwick is interesting to behold:

”This constant succession of glasses produced considerable effect upon Mr. Pickwick; his countenance beamed with the most sunny smiles, laughter played around his lips, and good-humoured merriment twinkled in his eye. Yielding by degrees to the influence of the exciting liquid, rendered more so by the heat, Mr. Pickwick expressed a strong desire to recollect a song which he had heard in his infancy, and the attempt proving abortive, sought to stimulate his memory with more glasses of punch, which appeared to have quite a contrary effect; for, from forgetting the words of the song, he began to forget how to articulate any words at all; and finally, after rising to his legs to address the company in an eloquent speech, he fell into the barrow, and fast asleep, simultaneously.”

This brings me to a bunch – not a punch – of questions: Was it usual in the 1830s to indulge so freely in alcoholic beverages as Mr. Pickwick and his friends do? What might Dickens’s readers have thought about it at the time? And how does Dickens’s treatment of alcohol change – if it does – in the course of his writings? I have a feeling that in later novels, we see a lot more of the detrimental effects of too liberal a use of alcohol. Or is it just a question of class in Dickens – Mr. Pickwick is a well-to-do gentleman, whereas the drunkards in Hard Times, Bleak House and Our Mutual Friend are not.

Be that as it may, Mr. Pickwick having fallen asleep, our friends decide to leave him behind and finish the shooting bit of the day without him. He appears to be safe in his barrow for Mr. Wardle and the others, but it happens that the picnic took place no Sir Geoffrey’s neighbour’s grounds, and that this neighbour is an irascible and overweening man with the befitting title of Captain Boldwig, who will not have any trespassers on his property and even contemplates putting up spring guns [1]. Captain Boldwig is so annoyed by the view of the sleeping Mr. Pickwick, whom he considers to just feign being asleep, that he orders his gardener to wheel the man into the Pound, i.e. the pigsty, where Mr. Pickwick by and by recovers his senses, only to find himself surrounded by a crowd of gloaters who even throw vegetables at him.

It will probably not surprise us that as soon as his friends have got him out of that unenviable situation, Mr. Pickwick only briefly entertains the idea of having Captain Boldwig brought to justice for his treatment, because after all, as Mr. Wardle points out, they were trespassing – but that they all stop at a roadside tavern in order to … have some brandy-and-water to “keep up their good-humour”.

[1] According to a note in my Penguin issue, spring guns – i.e. hidden guns that could be triggered by a wire – were perfectly legal means of protecting your property from trespassers and, especially, poachers. They were made illegal, though, in 1827 by an Act of Parliament, which means that, the novel taking place around 1830, no longer is allowed to use them. But he does not seem to care.

Chapter 20 shows Dickens as a satirist, practising in a field which he would later deal with in more detail, and with more bitterness, in his masterpiece Bleak House, viz. the way that legal men “look after” the interests of their clients.

Mr. Pickwick has acted on his intention to have a word with Messrs Dodson and Fogg. Already the names of these two lawyers do not sound very encouraging to Mr. Pickwick’s enterprise of reason: “Fogg” speaks for itself and conjures up the masterful beginning of Bleak House, and “Dodson” makes me think of another “artful dodger”. When Mr. Pickwick arrives on the scene, he cannot, of course, talk immediately to the two lawyers because Mr. Dodson is out on business, and Mr. Fogg is engaged in it and must not be disturbed. Let’s use the time Mr. Pickwick is kept waiting to have a little look at how our narrator describes the surroundings:

Not only do we get adjectives such as “dingy”, “dark”, “mouldy”, “dirty” and “decayed” within two short paragraphs, but we also learn that looking out of the windows of the quasi-subterranean office would offer you nearly the same prospect as that of a man sitting in a “reasonably deep well”, and we can suspect that those unlucky people who fall into the clutches of Dodson and Fogg would be far better off in a deep well. The clerks to that establishment are screened off “from the vulgar gaze”, which is a first sign of Dodson and Fogg’s inclination to secrecy and underhandedness. So, within two paragraphs, our narrator has already carefully set the scene. Mr. Pickwick and Sam are now given the opportunity, as is the reader, to listen in on the clerks’ private conversations, and the impressions one may gain from looking at the place only, are immediately corroborated by a little story of how Fogg dealt with a debtor named Ramsey, who came to settle his debts. We learn that Fogg told him he was unfortunately too late to prevent a declaration from being filed, which would increase costs “materially”, and that after sending Ramsey away with the advice to scrape some more money together Fogg sent away one of his clerks with the self-same declaration he had had ready in his pocket to file it. Fogg justifies this mean trick by saying that Ramsey as “a steady man with a large family” and a modest, but secure income is a good customer for them, and that what he does in “a Christian act” because it is teaching Ramsey a lesson not to run into debt so quickly next time.

I really wonder, not so much at Dodson and Fogg’s baseness, but at the frankness with which the clerks discuss the shady business manners of their employers in the presence of Mr. Pickwick. Do they think he cannot hear them, or do they simply not care?

After a while, Mr. Pickwick reminds the clerks of his presence, and he is shown into the presence of Fogg, who is described as

As if by coincidence, Mr. Dodson, too, appears on the scene, and between the two of them, Mr. Pickwick stands no chance of clarifying the misunderstanding, which is so profitable for the two lawyers. Mark how expertly they run down Mr. Pickwick, assuming the high ground of outraged morality and simultaneously not committing themselves to any positive statement of facts:

When Mr. Pickwick’s temper is understandably roused by these two legal vultures, they even start provoking him into further invectives and even into assaulting them, but Sam quickly comes to the rescue and drags the indignant Pickwick out of the office without much ceremony, clearly with a view of preventing his master from running himself into still deeper trouble. Out in the street, Mr. Pickwick decides to inform his legal representative, Mr. Perker, of the case and to authorize him to act on his behalf.

Things do not look to well for Mr. Pickwick, apparently. Do you think that Mr. Perker will be a match for the two master-villains Dodson and Fogg? Maybe, Mrs. Bardell will think better of the whole case if Mr. Pickwick talks with her? Why doesn’t he?

Mr. Pickwick is so worked up from his interview with the liars … ahem lawyers that he does what he seems to be doing quite often – he refreshes himself with a little drink in an inn which Sam seems to know particularly well, which can probably be said of many a public house in London. As chance would have it, they meet a coachman in that place, who turns out to be Mr. Weller, senior, and since Sam has not seen his father for about two years, they make use of the situation to enjoy another convivial glass of something. In the course of their conversation, Mr. Pickwick not only learns an infallible remedy for gout from Old Mr. Weller –

but they also get new information on the whereabouts of Mr. Jingle and Mr. Trotter, whom Old Weller has taken to Ipswich. This new information takes Mr. Pickwick’s mind off his own troubles for a while and makes him take the resolution to go to Ipswich in order to have it out with the two rogues. When they finally take leave, they notice that Mr. Perker’s office is already closed but they get information to the effect that Mr. Perker’s clerk, Mr. Lowten, usually spends his nights at the Magpie and Stump, whither they go accordingly. Here, Mr. Pickwick is admitted into another convivial circle, this time, of clerks. Not only can he authorize Mr. Perker via his clerk to act for him, but he also is invited to spend half-an-hour at their table, an offer which he takes up – out of common interest in the study of human affairs, and probably not so much with a view to the drinks served there. As is often the case, the arrival of a new and unknown party casts an initial damp on the company but eventually, an older clerk named Jack Bamber volunteers to tell a story. Our narrator uses this opportunity to insert a clever cliff-hanger by postponing this story into the next chapter, and the next instalment. In order to make his readers all the more curious, he gives a haunting description of the old man:

Hmm, what kind of story can be expected from an eerie individual like Mr. Bamber? We will have to wait and see …

One Wellerism: “’[…] I think he’s the wictim o’ connubiality, as Blue Beard’s domestic chaplain said, vith a tear of pity, ven he buried him.’”

And one question: What do you think of Sam’s relationship with his father? They seem to talk to each other in a rather off-handed way, and apparently they don’t see each other for long spells of time.

Mr. Pickwick has acted on his intention to have a word with Messrs Dodson and Fogg. Already the names of these two lawyers do not sound very encouraging to Mr. Pickwick’s enterprise of reason: “Fogg” speaks for itself and conjures up the masterful beginning of Bleak House, and “Dodson” makes me think of another “artful dodger”. When Mr. Pickwick arrives on the scene, he cannot, of course, talk immediately to the two lawyers because Mr. Dodson is out on business, and Mr. Fogg is engaged in it and must not be disturbed. Let’s use the time Mr. Pickwick is kept waiting to have a little look at how our narrator describes the surroundings:

”In the ground-floor front of a dingy house, at the very farthest end of Freeman’s Court, Cornhill, sat the four clerks of Messrs. Dodson & Fogg, two of his Majesty’s attorneys of the courts of King’s Bench and Common Pleas at Westminster, and solicitors of the High Court of Chancery—the aforesaid clerks catching as favourable glimpses of heaven’s light and heaven’s sun, in the course of their daily labours, as a man might hope to do, were he placed at the bottom of a reasonably deep well; and without the opportunity of perceiving the stars in the day-time, which the latter secluded situation affords.

The clerks’ office of Messrs. Dodson & Fogg was a dark, mouldy, earthy-smelling room, with a high wainscotted partition to screen the clerks from the vulgar gaze, a couple of old wooden chairs, a very loud-ticking clock, an almanac, an umbrella-stand, a row of hat-pegs, and a few shelves, on which were deposited several ticketed bundles of dirty papers, some old deal boxes with paper labels, and sundry decayed stone ink bottles of various shapes and sizes.”

Not only do we get adjectives such as “dingy”, “dark”, “mouldy”, “dirty” and “decayed” within two short paragraphs, but we also learn that looking out of the windows of the quasi-subterranean office would offer you nearly the same prospect as that of a man sitting in a “reasonably deep well”, and we can suspect that those unlucky people who fall into the clutches of Dodson and Fogg would be far better off in a deep well. The clerks to that establishment are screened off “from the vulgar gaze”, which is a first sign of Dodson and Fogg’s inclination to secrecy and underhandedness. So, within two paragraphs, our narrator has already carefully set the scene. Mr. Pickwick and Sam are now given the opportunity, as is the reader, to listen in on the clerks’ private conversations, and the impressions one may gain from looking at the place only, are immediately corroborated by a little story of how Fogg dealt with a debtor named Ramsey, who came to settle his debts. We learn that Fogg told him he was unfortunately too late to prevent a declaration from being filed, which would increase costs “materially”, and that after sending Ramsey away with the advice to scrape some more money together Fogg sent away one of his clerks with the self-same declaration he had had ready in his pocket to file it. Fogg justifies this mean trick by saying that Ramsey as “a steady man with a large family” and a modest, but secure income is a good customer for them, and that what he does in “a Christian act” because it is teaching Ramsey a lesson not to run into debt so quickly next time.

I really wonder, not so much at Dodson and Fogg’s baseness, but at the frankness with which the clerks discuss the shady business manners of their employers in the presence of Mr. Pickwick. Do they think he cannot hear them, or do they simply not care?

After a while, Mr. Pickwick reminds the clerks of his presence, and he is shown into the presence of Fogg, who is described as

” an elderly, pimply-faced, vegetable-diet sort of man, in a black coat, dark mixture trousers, and small black gaiters; a kind of being who seemed to be an essential part of the desk at which he was writing, and to have as much thought or feeling.”

As if by coincidence, Mr. Dodson, too, appears on the scene, and between the two of them, Mr. Pickwick stands no chance of clarifying the misunderstanding, which is so profitable for the two lawyers. Mark how expertly they run down Mr. Pickwick, assuming the high ground of outraged morality and simultaneously not committing themselves to any positive statement of facts:

”‘For the grounds of action, sir,’ continued Dodson, with moral elevation in his air, ‘you will consult your own conscience and your own feelings. We, Sir, we, are guided entirely by the statement of our client. That statement, Sir, may be true, or it may be false; it may be credible, or it may be incredible; but, if it be true, and if it be credible, I do not hesitate to say, Sir, that our grounds of action, Sir, are strong, and not to be shaken. You may be an unfortunate man, Sir, or you may be a designing one; but if I were called upon, as a juryman upon my oath, Sir, to express an opinion of your conduct, Sir, I do not hesitate to assert that I should have but one opinion about it.’ Here Dodson drew himself up, with an air of offended virtue, and looked at Fogg, who thrust his hands farther in his pockets, and nodding his head sagely, said, in a tone of the fullest concurrence, ‘Most certainly.’

‘Well, Sir,’ said Mr. Pickwick, with considerable pain depicted in his countenance, ‘you will permit me to assure you that I am a most unfortunate man, so far as this case is concerned.’

‘I hope you are, Sir,’ replied Dodson; ‘I trust you may be, Sir. If you are really innocent of what is laid to your charge, you are more unfortunate than I had believed any man could possibly be. What do you say, Mr. Fogg?’”

When Mr. Pickwick’s temper is understandably roused by these two legal vultures, they even start provoking him into further invectives and even into assaulting them, but Sam quickly comes to the rescue and drags the indignant Pickwick out of the office without much ceremony, clearly with a view of preventing his master from running himself into still deeper trouble. Out in the street, Mr. Pickwick decides to inform his legal representative, Mr. Perker, of the case and to authorize him to act on his behalf.

Things do not look to well for Mr. Pickwick, apparently. Do you think that Mr. Perker will be a match for the two master-villains Dodson and Fogg? Maybe, Mrs. Bardell will think better of the whole case if Mr. Pickwick talks with her? Why doesn’t he?

Mr. Pickwick is so worked up from his interview with the liars … ahem lawyers that he does what he seems to be doing quite often – he refreshes himself with a little drink in an inn which Sam seems to know particularly well, which can probably be said of many a public house in London. As chance would have it, they meet a coachman in that place, who turns out to be Mr. Weller, senior, and since Sam has not seen his father for about two years, they make use of the situation to enjoy another convivial glass of something. In the course of their conversation, Mr. Pickwick not only learns an infallible remedy for gout from Old Mr. Weller –

”‘The gout, Sir,’ replied Mr. Weller, ‘the gout is a complaint as arises from too much ease and comfort. If ever you’re attacked with the gout, sir, jist you marry a widder as has got a good loud woice, with a decent notion of usin’ it, and you’ll never have the gout agin. It’s a capital prescription, sir. I takes it reg’lar, and I can warrant it to drive away any illness as is caused by too much jollity.’ Having imparted this valuable secret, Mr. Weller drained his glass once more, produced a laboured wink, sighed deeply, and slowly retired.” –

but they also get new information on the whereabouts of Mr. Jingle and Mr. Trotter, whom Old Weller has taken to Ipswich. This new information takes Mr. Pickwick’s mind off his own troubles for a while and makes him take the resolution to go to Ipswich in order to have it out with the two rogues. When they finally take leave, they notice that Mr. Perker’s office is already closed but they get information to the effect that Mr. Perker’s clerk, Mr. Lowten, usually spends his nights at the Magpie and Stump, whither they go accordingly. Here, Mr. Pickwick is admitted into another convivial circle, this time, of clerks. Not only can he authorize Mr. Perker via his clerk to act for him, but he also is invited to spend half-an-hour at their table, an offer which he takes up – out of common interest in the study of human affairs, and probably not so much with a view to the drinks served there. As is often the case, the arrival of a new and unknown party casts an initial damp on the company but eventually, an older clerk named Jack Bamber volunteers to tell a story. Our narrator uses this opportunity to insert a clever cliff-hanger by postponing this story into the next chapter, and the next instalment. In order to make his readers all the more curious, he gives a haunting description of the old man:

”The individual to whom Lowten alluded, was a little, yellow, high-shouldered man, whose countenance, from his habit of stooping forward when silent, Mr. Pickwick had not observed before. He wondered, though, when the old man raised his shrivelled face, and bent his gray eye upon him, with a keen inquiring look, that such remarkable features could have escaped his attention for a moment. There was a fixed grim smile perpetually on his countenance; he leaned his chin on a long, skinny hand, with nails of extraordinary length; and as he inclined his head to one side, and looked keenly out from beneath his ragged gray eyebrows, there was a strange, wild slyness in his leer, quite repulsive to behold.”

Hmm, what kind of story can be expected from an eerie individual like Mr. Bamber? We will have to wait and see …

One Wellerism: “’[…] I think he’s the wictim o’ connubiality, as Blue Beard’s domestic chaplain said, vith a tear of pity, ven he buried him.’”

And one question: What do you think of Sam’s relationship with his father? They seem to talk to each other in a rather off-handed way, and apparently they don’t see each other for long spells of time.

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 19 is mainly based on slapstick, which is not to say that it is less interesting, and it might give us an idea of what Pickwick Papers could have looked like, had Dickens not finally had hi..."

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 19 is mainly based on slapstick, which is not to say that it is less interesting, and it might give us an idea of what Pickwick Papers could have looked like, had Dickens not finally had hi..."Nice observation, Tristram, of the plight of the birds foreshadowing the troubles Mr. Pickwick gets himself into later. This is the sort of thing I don't generally pick up on, but when you all point it out, it makes my (post) reading experience so much richer!

My first reading of this chapter put me in tears of laughter at Mr. Pickwick's inebriated plight. This time, undoubtedly due to life being a bit more complex these days, I greatly enjoyed the picnic scene, but felt differently about Mr. Pickwick's incarceration. Rather than see the slapstick humor, I found myself imagining being in a situation in which I was confused, humiliated, and having strangers pelting me with rotten food. I felt quite sorry for Pickwick, and relieved when his friends came to his rescue. My sympathies didn't extend to approving of his bringing charges against Boldwig (another wonderful name!), and I was pleased that Wardle was able to talk him down -- and with the good humor we've come to expect from this group.

In another book's discussion I mentioned Dickens' descriptive talents and remarked that modern authors seemed only able to add a modicum of depth to a scene by describing the food. Someone - Peter perhaps? - pointed out that Dickens often used food in the same way, and Pickwick has certainly proven him right! And yet, Dickens manages to do it in a way that not only has me enjoying the passages, but actually looking forward to them, like a sumptuous holiday feast. But, like James Herriot's books were really about people and not animals, Dickens' meal passages tell us more about the people at the table than the food itself. And that's the mastery of the author. I continue to be awed.

Tristram wrote: "What do you think of Sam’s relationship with his father? They seem to talk to each other in a rather off-handed way, and apparently they don’t see each other for long spells of time...."

Tristram wrote: "What do you think of Sam’s relationship with his father? They seem to talk to each other in a rather off-handed way, and apparently they don’t see each other for long spells of time...."I find that I'm enjoying the company of Mr. Weller, Sr. much more than that of his son. Frankly, I don't understand half of Sam's Wellerisms (am I the only one?) and Mr. Weller's straight-forward humor is a breath of fresh air after Sam's riddles. As to their relationship, there's an exchange on this subject coming up in the next set of chapters that made me laugh. I'll save comment on it for the appropriate time.

Tristram wrote: "Dear Fellow Curiosities,

This week, our Pickwickian adventures will again offer us a whole Dickensian range of impressions, starting from a domestic scene of comic tragedy, going then into the rea..."

Tristram

Yes. Your comments about the seemingly high number of “imperious” wives does make one wonder, especially since the Victorian wife, for the most part, were rather powerless in their roles. Added to that, as we have seen, most of the young unmarried female characters in Dickens’s novels are innocent - some would say rather sappy - in their presentation.

It seems that most times when we see Dickens deviate from the norm of the female character we get very eccentric, powerful, and memorable women. Sarah Gamp, Miss Wade, and even Lady Deadlock stand out in addition to the women mentioned earlier.

I also think of Mrs Jerry Cruncher. She is one of the few women who are fully dominated by a husband. His treatment of her is definitely not humourous to a modern reader. In the 19C, however, a strong and eccentric women character must have been a delight for the contemporary reader.

I really loved Pickwick’s observation that “is it not a wonderful circumstance ... that we seem destined to enter no man’s house without involving him in some degree of trouble.” Should we all bar our doors if The Pickwickians come a calling?

This week, our Pickwickian adventures will again offer us a whole Dickensian range of impressions, starting from a domestic scene of comic tragedy, going then into the rea..."

Tristram

Yes. Your comments about the seemingly high number of “imperious” wives does make one wonder, especially since the Victorian wife, for the most part, were rather powerless in their roles. Added to that, as we have seen, most of the young unmarried female characters in Dickens’s novels are innocent - some would say rather sappy - in their presentation.

It seems that most times when we see Dickens deviate from the norm of the female character we get very eccentric, powerful, and memorable women. Sarah Gamp, Miss Wade, and even Lady Deadlock stand out in addition to the women mentioned earlier.

I also think of Mrs Jerry Cruncher. She is one of the few women who are fully dominated by a husband. His treatment of her is definitely not humourous to a modern reader. In the 19C, however, a strong and eccentric women character must have been a delight for the contemporary reader.

I really loved Pickwick’s observation that “is it not a wonderful circumstance ... that we seem destined to enter no man’s house without involving him in some degree of trouble.” Should we all bar our doors if The Pickwickians come a calling?

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 19 is mainly based on slapstick, which is not to say that it is less interesting, and it might give us an idea of what Pickwick Papers could have looked like, had Dickens not finally had hi..."

Tristram

I really enjoyed your comments on Dickens and drink. I too think that the way Dickens portrayed the effect of alcohol on people moved from one of broad-based humour and joyous camaraderie to one of how alcohol has harmed, or ruined and destroyed both the person who was the drinker and those who were part of their sphere.

Dickens humourous writings on alcohol was one of the reasons that he and his one-time illustrator George Cruikshank parted ways. Cruikshank became very passionate against drinking. Dickens, for his part, commented in some of his letters that he both enjoyed, and, at times, overindulged in drinking.

The visual image of Pickwick in a wheelbarrow is exquisite.

“I don’t care whether it’s unsportsmanlike-like or not, “ replied Mr. Pickwick; ‘I am not going to be shot in a wheelbarrow, for the sake of appearances, to please anybody.”

Perfect image, is it not?

Tristram

I really enjoyed your comments on Dickens and drink. I too think that the way Dickens portrayed the effect of alcohol on people moved from one of broad-based humour and joyous camaraderie to one of how alcohol has harmed, or ruined and destroyed both the person who was the drinker and those who were part of their sphere.

Dickens humourous writings on alcohol was one of the reasons that he and his one-time illustrator George Cruikshank parted ways. Cruikshank became very passionate against drinking. Dickens, for his part, commented in some of his letters that he both enjoyed, and, at times, overindulged in drinking.

The visual image of Pickwick in a wheelbarrow is exquisite.

“I don’t care whether it’s unsportsmanlike-like or not, “ replied Mr. Pickwick; ‘I am not going to be shot in a wheelbarrow, for the sake of appearances, to please anybody.”

Perfect image, is it not?

I live in a valley filled with men (and perhaps women, I never checked) who love to hunt and the part with the dog pointing and the guns going off when they weren't supposed to had me having to stop because I was laughing so hard. There are a few men I know I would just love to read that part to. :-)

You mentioned Tristram and I wondered, when the clerks were having a wonderful telling how awful the men they worked for were, wasn't that an extremely stupid thing to do? What if Pickwick had been a new client? Or someone coming in for the first time needing a lawyer. I know after hearing that I'd go out the door again.

Mr. Pickwick in the Pound

Chapter 19

Phiz

1836

Text Illustrated:

‘Wheel him,’ said the captain—‘wheel him to the pound; and let us see whether he calls himself Punch when he comes to himself. He shall not bully me—he shall not bully me. Wheel him away.’

Away Mr. Pickwick was wheeled in compliance with this imperious mandate; and the great Captain Boldwig, swelling with indignation, proceeded on his walk.

Inexpressible was the astonishment of the little party when they returned, to find that Mr. Pickwick had disappeared, and taken the wheel-barrow with him. It was the most mysterious and unaccountable thing that was ever heard of. For a lame man to have got upon his legs without any previous notice, and walked off, would have been most extraordinary; but when it came to his wheeling a heavy barrow before him, by way of amusement, it grew positively miraculous. They searched every nook and corner round, together and separately; they shouted, whistled, laughed, called—and all with the same result. Mr. Pickwick was not to be found. After some hours of fruitless search, they arrived at the unwelcome conclusion that they must go home without him.

Meanwhile Mr. Pickwick had been wheeled to the Pound, and safely deposited therein, fast asleep in the wheel-barrow, to the immeasurable delight and satisfaction not only of all the boys in the village, but three-fourths of the whole population, who had gathered round, in expectation of his waking. If their most intense gratification had been awakened by seeing him wheeled in, how many hundredfold was their joy increased when, after a few indistinct cries of ‘Sam!’ he sat up in the barrow, and gazed with indescribable astonishment on the faces before him.

A general shout was of course the signal of his having woke up; and his involuntary inquiry of ‘What’s the matter?’ occasioned another, louder than the first, if possible.

‘Here’s a game!’ roared the populace.

‘Where am I?’ exclaimed Mr. Pickwick.

‘In the pound,’ replied the mob.

‘How came I here? What was I doing? Where was I brought from?’

Boldwig! Captain Boldwig!’ was the only reply.

‘Let me out,’ cried Mr. Pickwick. ‘Where’s my servant? Where are my friends?’

‘You ain’t got no friends. Hurrah!’ Then there came a turnip, then a potato, and then an egg; with a few other little tokens of the playful disposition of the many-headed.

Mr. Pickwick and Sam in the Attorney's Office

Chapter 20

Phiz

1836

Text Illustrated:

‘Nice men these here, Sir,’ whispered Mr. Weller to his master; ‘wery nice notion of fun they has, Sir.’

Mr. Pickwick nodded assent, and coughed to attract the attention of the young gentlemen behind the partition, who, having now relaxed their minds by a little conversation among themselves, condescended to take some notice of the stranger.

‘I wonder whether Fogg’s disengaged now?’ said Jackson.

‘I’ll see,’ said Wicks, dismounting leisurely from his stool. ‘What name shall I tell Mr. Fogg?’

‘Pickwick,’ replied the illustrious subject of these memoirs.

Mr. Jackson departed upstairs on his errand, and immediately returned with a message that Mr. Fogg would see Mr. Pickwick in five minutes; and having delivered it, returned again to his desk.

‘What did he say his name was?’ whispered Wicks.

‘Pickwick,’ replied Jackson; ‘it’s the defendant in Bardell and Pickwick.’

A sudden scraping of feet, mingled with the sound of suppressed laughter, was heard from behind the partition.

‘They’re a-twiggin’ of you, Sir,’ whispered Mr. Weller.

‘Twigging of me, Sam!’ replied Mr. Pickwick; ‘what do you mean by twigging me?’

Mr. Weller replied by pointing with his thumb over his shoulder, and Mr. Pickwick, on looking up, became sensible of the pleasing fact, that all the four clerks, with countenances expressive of the utmost amusement, and with their heads thrust over the wooden screen, were minutely inspecting the figure and general appearance of the supposed trifler with female hearts, and disturber of female happiness. On his looking up, the row of heads suddenly disappeared, and the sound of pens travelling at a furious rate over paper, immediately succeeded.

Mr. Winkle

Chapter 19

Thomas Nast

Text Illustrated:

Meanwhile, Mr. Winkle flashed, and blazed, and smoked away, without producing any material results worthy of being noted down; sometimes expending his charge in mid-air, and at others sending it skimming along so near the surface of the ground as to place the lives of the two dogs on a rather uncertain and precarious tenure. As a display of fancy-shooting, it was extremely varied and curious; as an exhibition of firing with any precise object, it was, upon the whole, perhaps a failure. It is an established axiom, that ‘every bullet has its billet.’ If it apply in an equal degree to shot, those of Mr. Winkle were unfortunate foundlings, deprived of their natural rights, cast loose upon the world, and billeted nowhere."

Making a Point — "What's the matter with the dogs' legs?"

Chapter 19

Felix O. C. Darley

1861

Text Illustrated:

"That gun of Tupman's is not safe: I know it isn't," said Mr. Pickwick.

"Eh? What! not safe?" said Mr. Tupman, in a tone of great alarm.

"Not as you are carrying it," said Mr. Pickwick. "I am very sorry to make any further objection, but I cannot consent to go on, unless you carry it as Winkle does his."

"I think you had better, sir," said the long gamekeeper, "or you're quite as likely to lodge the charge in yourself as in anything else."

Mr. Tupman, with the most obliging haste, placed his piece in the position required, and the party moved on again; the two amateurs marching with reversed arms, l ike a couple of privates at a royal funeral.

The dogs suddenly came to a dead stop, and the party advancing stealthily a single pace, stopped too.

"What's the matter with the dogs' legs?" whispered Mr. Winkle. "How queer they're standing."

"Hush, can't you?" replied Wardle softly. "Don't you see, they're making a point?"

"Making a point!" said Mr. Winkle, staring about him, as if he expected to discover some particular beauty in the landscape, which the sagacious animals were calling special attention to. "Making a point! What are they pointing at?"

"Keep your eyes open," said Wardle, not heeding the question in the excitement of the moment. "Now then."

There was a sharp whirring noise, that made Mr. Winkle start back as if he had been shot himself. Bang, bang, went a couple of guns — the smoke swept quickly away over the field, and curled into the air.

"Where are they!" said Mr. Winkle, in a state of the highest excitement, turning round and round in all directions. "Where are they? Tell me when to fire. Where are they — where are they?"

"Where are they!" said Wardle, taking up a brace of birds which the dogs had deposited at his feet. "Why, here they are."

Commentary:

The four 1861 frontispieces for the first four separate volumes of The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club in the fifty-five volume set by a renowned American illustrator, Felix Octavius Carr Darley (then 39 and well established as a professional artist) and well-known British illustrator Sir John Gilbert, were a value-added feature for New York publisher James M. Gregory. Although beautifully printed and bound, the green volumes are essentially an American piracy since Dickens had assigned publication rights to Harper and Brothers.

Having already demonstrated his ineptitude in the handling of a horse and carriage in the streets of Rochester, Pickwick leads his companions on a September partridge hunt, but at least the impractical, bourgeois urbanites are now accompanied by the ever-prepared Sam Weller as they hunt game birds on Sir Geoffrey Manning's estate. Thus, Dickens delays for another few days Pickwick's confronting unscrupulous attorneys Dodson and Fogg about Mrs. Bardell's breach-of-promise suit.

Neither American Household Edition illustrator of the seventies, Thomas Nast, nor the successor to Robert Seymour (whose suicide with a firearm caused an abrupt change of illustrator for the monthly serial), Phiz selected for their series of illustrations this farcical hunting scene. Phiz decided upon the famous scene later in chapter 19, Mr. Pickwick in the Pound (1836), and forty years later in the Household Edition a subsequent hunting mishap, There was a scream as of an individual — not a rook — in corporeal anguish. Mr. Tupman had saved the lives of innumerable unoffending birds by receiving a portion of the charge in his left arm (1874), while Nast focuses on the ridiculous spectacle of Winkle in hunting garb, Mr. Winkle (1873). All three treatments are much funnier and more cartoon-like than Darley's, which may be taken as a limitation of the realist's response to the caricature style of illustration dominant in the 1840s.

Darley's choice of scene is interesting, however, in that it is another piece of the type of humor exploited by Robert Smith Surtees' (17 May 1805-16 March 1864) Cockney sporting series in the early 1830s in The New Sporting Magazine, although his volume work Jorrocks' Jaunts and Jollities actually came out after Dickens's Pickwick in 1838. The immediate origin of Dickens's Pickwickians was, in fact, Robert Seymour's "Nimrod Club" proposal to Chapman and Hall in 1835. In this satire of a traditional male hunting scene, the lame Pickwick is improbably in a wheel-barrow as his bumbling fellow club-members Mr. Winkle and Mr. Tupman, accompanied by Mr. Wardle, the owner of the idyllic Kentish estate of Manor Farm at the village of Dingley Dell, once more make fools of themselves outside their comfort zone, London. To add to the reader's amusement, Winkle, pretending to be something of a sportsman, mishandles his shotgun in such a manner that the reader apprehends a shooting accident is likely to occur — suspicions immediately confirmed by Winkle's accidentally discharging his firearm in the direction of the tall gamekeeper. Yet another complication is that Sir Geoffrey Manning's gamekeeper, Martin, has instructed his assistant to meet the shooting party on One-tree Hill, which is located on the estate of pompous and quick-tempered Captain Boldwig — setting up Pickwick's arrest for trespassing and being incarcerated with errant animals in a village "pound." Taken in sum, the shooting scene, then, constitutes the comedy of menace, a recurring feature of this picaresque novel.

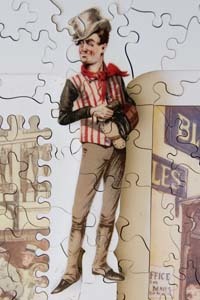

Chapter 19

T. Onwhyn and Sam Weller

The Pickwick Illustrations

1837

Text Illustrated:

‘Keep your eyes open,’ said Wardle, not heeding the question in the excitement of the moment. ‘Now then.’

There was a sharp whirring noise, that made Mr. Winkle start back as if he had been shot himself. Bang, bang, went a couple of guns—the smoke swept quickly away over the field, and curled into the air.

‘Where are they!’ said Mr. Winkle, in a state of the highest excitement, turning round and round in all directions. ‘Where are they? Tell me when to fire. Where are they—where are they?’

‘Where are they!’ said Wardle, taking up a brace of birds which the dogs had deposited at his feet. ‘Why, here they are.’

‘No, no; I mean the others,’ said the bewildered Winkle.

‘Far enough off, by this time,’ replied Wardle, coolly reloading his gun.

‘We shall very likely be up with another covey in five minutes,’ said the long gamekeeper. ‘If the gentleman begins to fire now, perhaps he’ll just get the shot out of the barrel by the time they rise.’

‘Ha! ha! ha!’ roared Mr. Weller.

‘Sam,’ said Mr. Pickwick, compassionating his follower’s confusion and embarrassment.

‘Sir.’

‘Don’t laugh.’

‘Certainly not, Sir.’ So, by way of indemnification, Mr. Weller contorted his features from behind the wheel-barrow, for the exclusive amusement of the boy with the leggings, who thereupon burst into a boisterous laugh, and was summarily cuffed by the long gamekeeper, who wanted a pretext for turning round, to hide his own merriment.

‘Bravo, old fellow!’ said Wardle to Mr. Tupman; ‘you fired that time, at all events.’

‘Weal pie,’ said Mr. Weller, soliloquising, as he arranged the eatables on the grass.

Chapter 19

T. Onwhyn and Sam Weller

1837

Text Illustrated:

‘Why,’ said the old gentleman, ‘pretty hot. It’s past twelve, though. You see that green hill there?’

‘Certainly.’

‘That’s the place where we are to lunch; and, by Jove, there’s the boy with the basket, punctual as clockwork!’

‘So he is,’ said Mr. Pickwick, brightening up. ‘Good boy, that. I’ll give him a shilling, presently. Now, then, Sam, wheel away.’

‘Hold on, sir,’ said Mr. Weller, invigorated with the prospect of refreshments. ‘Out of the vay, young leathers. If you walley my precious life don’t upset me, as the gen’l’m’n said to the driver when they was a-carryin’ him to Tyburn.’ And quickening his pace to a sharp run, Mr. Weller wheeled his master nimbly to the green hill, shot him dexterously out by the very side of the basket, and proceeded to unpack it with the utmost despatch.

‘Weal pie,’ said Mr. Weller, soliloquising, as he arranged the eatables on the grass. ‘Wery good thing is weal pie, when you know the lady as made it, and is quite sure it ain’t kittens; and arter all though, where’s the odds, when they’re so like weal that the wery piemen themselves don’t know the difference?’

"Who are you, you rascal?" said the captain, administering several pokes to Mr. Pickwick's body with the thick stick. "What's your name?"

Chapter 19

Phiz

1874 Household Edition

Commentary:

As critics have noted, the objects and characters in Phiz's original illustration — notably the braying donkey and three pigs — convey important meanings. No one, however, has commented upon the presence of a beadle or local municipal legal authority and a monkey (center, above Pickwick) holding aloft a turnip or apple. Curiously, in preparing his series of fifty-seven woodcuts for the 1874 Household Edition Phiz elected not to redraft this highly effective engraving, choosing instead to depict the scene in which the irate landowner, Captain Boldwig, has the sleeping Pickwick impounded for trespass. Robert Patten has noted that the donkey and swine may point to a biblical interpretation, although he does not note that swine were the companions of the Prodigal Son in the Christian parable:

Mr. Pickwick comes to the pound through his own follies: the folly of being out on a rainy night, hiding in a private garden to prevent the elopement of a stranger; the folly of watching a shooting expedition from a wheelbarrow; the folly of consuming too much veal pie and imbibing too much cold punch. For correction, he is isolated from his fellow Pickwickians, and divided from the villagers by the wooden fence of the pound.

The pound is therefore a small, informal prison, separating errant characters from the larger community. In this instance, Mr. Pickwick's only companions are animals — asses and pigs. The illustration invites us to consider his behavior in the light of the traditional moral associations of these animals: the pigs seem emblems of sloth and gluttony; the donkeys, emblems of stubbornness. Browne's independent addition of these animals — none are mentioned in Dickens's text — is an example of how his artistic imagination complements Dickens'. Both seize on objects or figures that emblemize a scene.

The sixteenth plate for The Pickwick Papers (October 1836) illustrates the symbiotic relationship that quickly developed by Boz and Phiz after Seymour's death and his successor, Buss, was dismissed. In the original steel engraving, Pickwick, who still feels the effects of multiple glasses of cold punch, has been transported as a "drunken plebeian" in the wheelbarrow from the scene of his debauch on Captain Boldwig's land at One-tree Hill (the very name suggestive of Christian redemption through suffering) to the local impound. He is now surrounded by the villagers, a stray donkey (who apparently laughs at the inebriate), and three pigs, despite the fact that the text in chapter 19 Dickens mentions no such creatures as Pickwick's companions.

In the title-page vignette of the Household Edition, Phiz suggests by the fence-posts behind Pickwick and the wheelbarrow that the novel's dubious hero is indeed in the pound, but spares him the humiliation of being surrounded by three-quarters of the population of the village who pelt him with vegetables and "a few other little tokens of the playful disposition of the many-headed", that is, the mob. As Patten notes in "Boz, Phiz and Pickwick in the Pound," Phiz has juxtaposed the stray animals, the derisive villagers, and the tower of the village church for thematic purposes, so that it may seem odd that neither of the Household Edition illustrators chose to replicate this scene of the protagonist's social degradation as Pickwick awakes to find himself an object of scorn and without the support of Sam and his fellow Pickwickians. Remarks Patten points out in that "Pickwick's follies are the result of an excess of appetites that, in moderation, are beneficial" since they serve to reinforce camaraderie and fellowship. Phiz has placed him with other creatures whose appetites have led them astray.

Cohen notes that Browne and not Dickens surrounded Pickwick with animals suggestive of stubbornness and gluttony, icons that since the Middle Ages signify vice and "which contrast with the church towering overhead with its implicit promise of forgiveness". In the new plate, Phiz (like Nast) decided to depict instead the moment when Pickwick, still disoriented, unintentionally identifies himself by accident as "Punch," the unredeemed sinner of the popular street entertainment of the Punch and Judy Show. Like Mr. Pickwick, Mr. Punch is easily blinded by anger — he also beats his wife and thumbs his nose at propriety and the law (none of which fits the respectable Pickwick, of course).

Disregarding this identification (which the monkey-demon on the fence above Pickwick and the beadle in the 1837 engraving reinforce), let us examine the two 1874 woodcuts for their implications about Pickwick as a flawed hero, one whom we should not so much emulate as regard as imperfect, and therefore fallible and human. In 1873 although Nast and Phiz worked independently separated as they were by the North Atlantic, both selected precisely the same moment in chapter 19 to illustrate: "Who are you, you rascal?" said the captain, administering several pokes to Mr. Pickwick's body with the thick stick. "What's your name?" by Phiz in the Chapman and Hall Household Edition of Dickens's The Pickwick Papers, and simply "Who are you, you rascal?" by Thomas Nast in the Harper and Brothers' Household Edition. The passage realised in both illustrations is this, although in neither illustration does the under-gardener, Wilkins, have his hand to his hat in deference to the majestic Boldwig's authority:

"Well, Wilkins, what's the matter with you?" said Captain Boldwig.

"I beg your pardon, sir — but I think there have been trespassers here to-day."

"Ha!" said the captain, scowling around him.

"Yes, sir — they have been dining here, I think, sir."

"Why, damn their audacity, so they have," said Captain Boldwig, as the crumbs and fragments that were strewn upon the grass met his eye. 'They have actually been devouring their food here. I wish I had the vagabonds here!" said the captain, clenching the thick stick.

"I wish I had the vagabonds here," said the captain wrathfully.

"Beg your pardon, sir," said Wilkins, 'but —"

"But what? Eh?" roared the captain; and following the timid glance of Wilkins, his eyes encountered the wheel-barrow and Mr. Pickwick.

"Who are you, you rascal?" said the captain, administering several pokes to Mr. Pickwick's body with the thick stick. "What's your name?"

"Cold punch," murmured Mr. Pickwick, as he sank to sleep again.

"What?" demanded Captain Boldwig.

No reply.

"What did he say his name was? " asked the captain.

"Punch, I think, sir," replied Wilkins.

"That's his impudence — that's his confounded impudence," said Captain Boldwig. "He's only feigning to be asleep now," said the captain, in a high passion. "He's drunk; he's a drunken plebeian. Wheel him away, Wilkins, wheel him away directly."

"Where shall I wheel him to, sir?" inquired Wilkins, with great timidity.

"Wheel him to the devil," replied Captain Boldwig.

The Household Edition title-page vignette relates to "Pickwick in the Pound," while in the nineteenth chapter Phiz realises the earlier scene, depicting the protagonist discovered by two gardeners and Captain Boldwig (holding a thick rattan stick with a brass ferule), the irascible land-owner. Indignant at the telltale evidence of picknicking and trespass on his property, Boldwig orders his men to transport the "plebeian" Pickwick, in a drunken stupor in a wheelbarrow, and deposit him in the local pound, which serves as a jail for the village. The military man's interrogation of the inebriate is not assisted by Pickwick's giving his name as "Cold Punch." Of the two gardeners in Phiz's picture, we may assume that Wilkins is immediately behind the pompous Boldwig, and that the man with the trowel is Hunt. Similarly, Nast uses two cartoonist's tricks to establish the identities of the gardeners, for the "sub-gardener," Wilkins, is a thin, smockfrock-wearing peasant carrying an oversized watering can, while his superior, Hunt, a stouter individual, is in closer proximity to Boldwig, and wears more conventionally middle-class attire: an apron, a vest, and a shirt. The less intelligent Wilkins gapes, open-mouthed, at the trespasser, whereas Hunt scratches his head, not sure what to make of a respectably clad, elderly, middle-class gentleman in such a pose and embarrassing situation. The object, however, that establishes which of the two is Wilkins is somewhat improbable since the object of Boldwig's inspection is not to water potted plants. Nor is Nast's Boldwig particularly well realised as in the text the haughty landowner is "a little fierce man in a stiff black neckerchief and blue surtout . . . with a thick rattan stick".

Whereas Nast captures the Captain's bellicose nature and military bearing, Phiz more ably conveys through his coloured face, facial hair, and rotund figure something of Boldwig's pomposity. Moreover, Phiz's gardeners, who surround Pickwick rather than, as in Nast's woodcut, observe him, are humorous and engaging characters whose aprons and implements (the broom and the trowel) bespeak their occupation. The chief difference between the two compositions, however, is the central placement of the addled Pickwick in Phiz's, and Nast's central placement of Boldwig, thrusting his cane into the trespasser rather than gently prodding the drunkard. Nast employs the juxtaposition of the sleeping inebriate and the noble, aged oak above him to emphasise Pickwick's figure, and perhaps obliquely comment on the inappropriateness of a revered elder finding himself in such a compromised position through the immoderate consumption of an alcoholic beverage. Phiz has Pickwick semiconscious but unable to rise, his hat (the sign of his middle-class respectability) abandoned on the ground, whereas the much chubbier Pickwick of Nast's woodcut is still fast asleep, his hat still firmly planted on his head. If, as Sergeant Buzfuz in his courtroom peroration about Pickwick's character asserts, Pickwick is metaphorically a "serpent," that is, an interloper and deceiver, he has unwittingly enacted the role of the serpent in Eden in this plate, prodded not by the spear of the angel-warrior Gabriel as in Book Four of Paradise Lost, but by the rattan cane of the class-conscious, ex-military man Captain Boldwig.

"Who are you, you rascal?"

Chapter 19

Thomas Nast

1874 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

"Well, Wilkins, what's the matter with you?" said Captain Boldwig.

"I beg your pardon, sir — but I think there have been trespassers here to-day."

"Ha!" said the captain, scowling around him.

"Yes, sir — they have been dining here, I think, sir."

"Why, damn their audacity, so they have," said Captain Boldwig, as the crumbs and fragments that were strewn upon the grass met his eye. 'They have actually been devouring their food here. I wish I had the vagabonds here!" said the captain, clenching the thick stick.

"I wish I had the vagabonds here," said the captain wrathfully.

"Beg your pardon, sir," said Wilkins, 'but —"

"But what? Eh?" roared the captain; and following the timid glance of Wilkins, his eyes encountered the wheel-barrow and Mr. Pickwick.

"Who are you, you rascal?" said the captain, administering several pokes to Mr. Pickwick's body with the thick stick. "What's your name?"

"Cold punch," murmured Mr. Pickwick, as he sank to sleep again.

"Who are you, rascal?" said the captain.

Chapter 19

William Heath

Pickwickian Illustrations

1837

Text Illustrated:

"Well, Wilkins, what's the matter with you?" said Captain Boldwig.

"I beg your pardon, sir — but I think there have been trespassers here to-day."

"Ha!" said the captain, scowling around him.

"Yes, sir — they have been dining here, I think, sir."

"Why, damn their audacity, so they have," said Captain Boldwig, as the crumbs and fragments that were strewn upon the grass met his eye. 'They have actually been devouring their food here. I wish I had the vagabonds here!" said the captain, clenching the thick stick.

"I wish I had the vagabonds here," said the captain wrathfully.

"Beg your pardon, sir," said Wilkins, 'but —"

"But what? Eh?" roared the captain; and following the timid glance of Wilkins, his eyes encountered the wheel-barrow and Mr. Pickwick.

"Who are you, you rascal?" said the captain, administering several pokes to Mr. Pickwick's body with the thick stick. "What's your name?"

"Cold punch," murmured Mr. Pickwick, as he sank to sleep again.

Mr. Pickwick in The Pound

Chapter 19

Harold Copping

1924

Text Illustrated:

Meanwhile Mr. Pickwick had been wheeled to the Pound, and safely deposited therein, fast asleep in the wheel-barrow, to the immeasurable delight and satisfaction not only of all the boys in the village, but three-fourths of the whole population, who had gathered round, in expectation of his waking. If their most intense gratification had been awakened by seeing him wheeled in, how many hundredfold was their joy increased when, after a few indistinct cries of ‘Sam!’ he sat up in the barrow, and gazed with indescribable astonishment on the faces before him.

A general shout was of course the signal of his having woke up; and his involuntary inquiry of ‘What’s the matter?’ occasioned another, louder than the first, if possible.

‘Here’s a game!’ roared the populace.

‘Where am I?’ exclaimed Mr. Pickwick.

‘In the pound,’ replied the mob.

‘How came I here? What was I doing? Where was I brought from?’

Boldwig! Captain Boldwig!’ was the only reply.

‘Let me out,’ cried Mr. Pickwick. ‘Where’s my servant? Where are my friends?’

‘You ain’t got no friends. Hurrah!’ Then there came a turnip, then a potato, and then an egg; with a few other little tokens of the playful disposition of the many-headed.

"You just come avay," said Mr. Weller. "Battledore and Shuttlecock's a wery good game, vhen you an't the shuttlecock and two lawyers the battledores."

Chapter 20

Phiz

1874 Household Edition

Commentary:

After the misadventure of the wheelbarrow (commemorated in the title-page vignette of the American Household Edition) and his subsequent ignominy in the village pound, Pickwick returns to London to deal with Mrs. Bardell's attorneys, Dodson and Fogg — unwisely approaching the cunning lawyers without the assistance of his own legal advisor, Mr. Perker. Pickwick's error in judgment of defaming them in front of witnesses (although his accusations are undoubtedly true) is so egregious that both Nast and Phiz felt the scene worthy of realization, although the British Household Edition sets its scene in the attorneys' outer office (as in Phiz's original illustration of October 1836), while the American version captures Pickwick's Parthian shot as he descends the building's staircase afterwards.

In both instances, Sam Weller tries to prevent Pickwick's getting himself in further trouble, restraining his all-too-easily-angered employer. From the point of view of strict fidelity to text, Nast's treatment of the scene is superior; however, in terms of the comedy and characterization of Pickwick and the predatory attorneys, Phiz's has much more to offer the discerning — even if Dickens would not have approved of Phiz's moving the clerks' office from the lower story of the building and enacting the scene in the lawyers' office rather than on the stairs. In particular, Phiz effectively conveys the pride that the black-suited rogues take in their clever and unethical dealings (as we learn from their treatment of Ramsey, as narrated by one of the clerks earlier in the chapter).

In the Phiz illustration, Pickwick is already denouncing the "disgraceful and rascally proceedings" of Bardell's attorneys, while in the original engraving Pickwick and Sam are still waiting in the reception area, scrutinized by the attorneys' clerks as objects of amusement. The precise moment realized by Phiz in 1873 is this, even if the precise piece of dialogue that serves as the caption is uttered on the stairs, as Pickwick and Sam depart (as envisaged by Nast, with the attorneys at the top of the stairs and the clerks on the landing below):

'Very well, gentlemen, very well,' said Mr. Pickwick, rising in person and wrath at the same time; 'you shall hear from my solicitor, gentlemen."

"We shall be very happy to do so," said Fogg, rubbing his hands.

"Very," said Dodson, opening the door.

"And before I go, gentlemen," said the excited Mr. Pickwick, turning round on the landing, "permit me to say, that of all the disgraceful and rascally proceedings — —"

"Stay, sir, stay," interposed Dodson, with great politeness. "Mr. Jackson! Mr. Wicks!"

"Sir," said the two clerks, appearing at the bottom of the stairs.

"I merely want you to hear what this gentleman says," replied Dodson. "Pray, go on, sir — disgraceful and rascally proceedings, I think you said?"

"I did," said Mr. Pickwick, thoroughly roused. "I said, sir, that of all the disgraceful and rascally proceedings that ever were attempted, this is the most so. I repeat it, sir."

"You hear that, Mr. Wicks," said Dodson.

"You won't forget these expressions, Mr. Jackson?" said Fogg.

"Perhaps you would like to call us swindlers, sir," said Dodson.

"Pray do, sir, if you feel disposed; now pray do, sir."

"I do," said Mr. Pickwick. 'You are swindlers."

"Very good," said Dodson. "You can hear down there, I hope, Mr. Wicks?"

"Oh, yes, sir," said Wicks.

"You had better come up a step or two higher, if you can't," added Mr. Fogg. "Go on, sir; do go on. You had better call us thieves, sir; or perhaps You would like to assault one of us. Pray do it, Sir, if you would; we will not make the smallest resistance. Pray do it, sir."

As Fogg put himself very temptingly within the reach of Mr. Pickwick's clenched fist, there is little doubt that that gentleman would have complied with his earnest entreaty, but for the interposition of Sam, who, hearing the dispute, emerged from the office, mounted the stairs, and seized his master by the arm.

You just come away," said Mr. Weller. "Battledore and shuttlecock's a wery good game, vhen you ain't the shuttlecock and two lawyers the battledores, in which case it gets too excitin' to be pleasant. Come avay, sir. If you want to ease your mind by blowing up somebody, come out into the court and blow up me; but it's rayther too expensive work to be carried on here."

Phiz better communicates Pickwick's indignation, his fists clenched, as Sam attempts to make him see that saying nothing whatsoever to the scoundrels is in his best interests. Phiz's clerks, looking in through the door communicating to the outer office, are obviously enjoying the baiting, whereas Nast's clerks lack any expression. And, further, Sam's remonstrance is more effectively communicated by his body language and gesture of a raised hand (implying that Pickwick has said enough) in Phiz's 1873 illustration.

"Pray do it, sir!"

Chapter 20

Thomas Nast

Text Illustrated:

‘And before I go, gentlemen,’ said the excited Mr. Pickwick, turning round on the landing, ‘permit me to say, that of all the disgraceful and rascally proceedings—’

‘Stay, sir, stay,’ interposed Dodson, with great politeness. ‘Mr. Jackson! Mr. Wicks!’

‘Sir,’ said the two clerks, appearing at the bottom of the stairs.

‘I merely want you to hear what this gentleman says,’ replied Dodson. ‘Pray, go on, sir—disgraceful and rascally proceedings, I think you said?’

‘I did,’ said Mr. Pickwick, thoroughly roused. ‘I said, Sir, that of all the disgraceful and rascally proceedings that ever were attempted, this is the most so. I repeat it, sir.’

‘You hear that, Mr. Wicks,’ said Dodson.

‘You won’t forget these expressions, Mr. Jackson?’ said Fogg.

‘Perhaps you would like to call us swindlers, sir,’ said Dodson. ‘Pray do, Sir, if you feel disposed; now pray do, Sir.’

‘I do,’ said Mr. Pickwick. ‘You are swindlers.’

‘Very good,’ said Dodson. ‘You can hear down there, I hope, Mr. Wicks?’

‘Oh, yes, Sir,’ said Wicks.

‘You had better come up a step or two higher, if you can’t,’ added Mr. Fogg. ‘Go on, Sir; do go on. You had better call us thieves, Sir; or perhaps You would like to assault one of us. Pray do it, Sir, if you would; we will not make the smallest resistance. Pray do it, Sir.’

As Fogg put himself very temptingly within the reach of Mr. Pickwick’s clenched fist, there is little doubt that that gentleman would have complied with his earnest entreaty, but for the interposition of Sam, who, hearing the dispute, emerged from the office, mounted the stairs, and seized his master by the arm.

‘You just come away,’ said Mr. Weller. ‘Battledore and shuttlecock’s a wery good game, vhen you ain’t the shuttlecock and two lawyers the battledores, in which case it gets too excitin’ to be pleasant. Come avay, Sir. If you want to ease your mind by blowing up somebody, come out into the court and blow up me; but it’s rayther too expensive work to be carried on here.’

And without the slightest ceremony, Mr. Weller hauled his master down the stairs, and down the court, and having safely deposited him in Cornhill, fell behind, prepared to follow whithersoever he should lead.

Messrs. Dodson and Fogg

Chapter 20

Sol Eytinge

1867 Diamond Edition

Text Illustrated:

Up stairs Mr. Pickwick did step accordingly, leaving Sam Weller below. The room door of the one-pair back, bore inscribed in legible characters the imposing words, "Mr. Fogg"; and, having tapped thereat, and been desired to come in, Jackson ushered Mr. Pickwick into the presence.

"Is Mr. Dodson in?" inquired Mr. Fogg.

"Just come in, Sir," replied Jackson.

"Ask him to step here."

"Yes, sir." Exit Jackson.

"Take a seat, sir," said Fogg; "there is the paper, sir; my partner will be here directly, and we can converse about this matter, sir."

Mr. Pickwick took a seat and the paper, but, instead of reading the latter, peeped over the top of it, and took a survey of the man of business, who was an elderly, pimply-faced, vegetable-diet sort of man, in a black coat, dark mixture trousers, and small black gaiters, — a kind of being who seemed to be an essential part of the desk at which he was writing, and to have as much thought or sentiment.

After a few minutes' silence, Mr. Dodson, a plump, portly, stern-looking man, with a loud voice, appeared; and the conversation commenced.

"This is Mr. Pickwick," said Fogg.

"Ah! You are the defendant, sir, in Bardell and Pickwick?" said Dodson.

"I am, sir," replied Mr. Pickwick.

"Well, sir," said Dodson, "and what do you propose?"

"Ah!" said Fogg, thrusting his hands into his trousers' pockets, and throwing himself back in his chair, "what do you propose, Mr. Pickwick?"

"Hush, Fogg," said Dodson, "let me hear what Mr. Pickwick has to say."

"I came, gentlemen," said Mr. Pickwick, — gazing placidly on the two partners, — "I came here, gentlemen, to express the surprise with which I received your letter of the other day, and to inquire what grounds of action you can have against me."

"Grounds of —" Fogg had ejaculated this much, when he was stopped by Dodson.

"Mr. Fogg," said Dodson, "I am going to speak."

"I beg your pardon, Mr. Dodson," said Fogg

Commentary:

In this fifth full-page dual character study for the last novel in the compact American publication, (I still don't understand how the first book ended up last in the American publication) Eytinge introduces the unscrupulous legal team who have agreed to represent Mrs. Bardell in her suit for "breach of promise of marriage" against Mr. Pickwick. Although morally Pickwick feels superior to these manipulators of the law, in point of strategy he proves himself naïve and gullible.

Phiz's original serial illustration "Mr. Pickwick and Sam in the Attorney's Office" (plate) presents Pickwick being made the butt of jokes by Dodson and Fogg's clerks in chapter 20, rather than Pickwick's conference with his adversary's attorneys. In the 1873 Household Edition illustrations, however, Phiz does attempt such a scene, but fails to render the predatory lawyers as sufficiently stern and unyielding, although at least they are slender and corpulent contrasts in "You just come avay," said Mr. Weller. "Battledore and Shuttlecock's a wery good game, vhen you an't the shuttlecock and two lawyers the battledores," etc.. The pair are obviously highly amused by Pickwick's utterances; perhaps they hope to draw him into further indiscretions by laughing at him.

Eytinge more accurately captures the essence of these lawyers by their juxtaposition, postures, and faces, and of course responds appropriately to Dickens's descriptions of their clothing. Clearly the mercenary pair have no interest whatsoever in Pickwick's protestations of innocence, but are thoroughly serious about the fifteen hundred pounds in damages ("and not a farthing less,") that they intend to abstract from Pickwick, his temper rising at their oily glibness, Pickwick begins to denounce their conduct as "disgraceful and rascally proceedings" , but when the attorneys call in their clerks to bear witness to the plaintiff's describing them as "swindlers," Sam must intervene (this is the scene that Phiz later elected to realize, having not attempted to depict Mrs. Bardell's attorneys in the original serial).

‘You just come away,’ said Mr. Weller. ‘Battledore and shuttlecock’s a wery good game, vhen you ain’t the shuttlecock and two lawyers the battledores, in which case it gets too excitin’ to be pleasant.

Chapter 20

T. Onwhyn and Sam Weller

The Pickwick Illustrations

1837

Text Illustrated:

‘You had better come up a step or two higher, if you can’t,’ added Mr. Fogg. ‘Go on, Sir; do go on. You had better call us thieves, Sir; or perhaps You would like to assault one of us. Pray do it, Sir, if you would; we will not make the smallest resistance. Pray do it, Sir.’

As Fogg put himself very temptingly within the reach of Mr. Pickwick’s clenched fist, there is little doubt that that gentleman would have complied with his earnest entreaty, but for the interposition of Sam, who, hearing the dispute, emerged from the office, mounted the stairs, and seized his master by the arm.

‘You just come away,’ said Mr. Weller. ‘Battledore and shuttlecock’s a wery good game, vhen you ain’t the shuttlecock and two lawyers the battledores, in which case it gets too excitin’ to be pleasant. Come avay, Sir. If you want to ease your mind by blowing up somebody, come out into the court and blow up me; but it’s rayther too expensive work to be carried on here.’