Classics and the Western Canon discussion

Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics

>

Book Five

Did Roman practice have anything comparable to the Jewish practice of the year of the Jubilee -- that is, for the sake of discussion here, any institutions or laws or practices that tended to distribute material wealth that had aggregated to selected parts (families?) to broader or different segments of the population.

Did Roman practice have anything comparable to the Jewish practice of the year of the Jubilee -- that is, for the sake of discussion here, any institutions or laws or practices that tended to distribute material wealth that had aggregated to selected parts (families?) to broader or different segments of the population.

Lily wrote: "Did Roman practice have anything comparable to the Jewish practice of the year of the Jubilee -- that is, for the sake of discussion here, any institutions or laws or practices that tended to distr..."

Lily wrote: "Did Roman practice have anything comparable to the Jewish practice of the year of the Jubilee -- that is, for the sake of discussion here, any institutions or laws or practices that tended to distr..."No.

However, some Greek cities (which I assume you meant) did try redistributing land among the citizens. The results are usually described, by members of the upper class, as bad, and some ancient historians go out of their way to condemn the practice, instead of just reporting it.

However, a partial parallel to the Jubilee, namely the liberation of slaves, is attributed to the half-legendary Athenian sage, Solon. During a crisis in Athens, he put through legislation which cancelled slavery for unpaid debts, freeing a lot of enslaved Athenians. However, he refused to return or otherwise redistribute land seized for debt. (So he wound up unpopular with both the wealthy creditors *and* the impoverished debtors.)

There is a decent Wikipedia article on Solon, with links to related material.

Ian wrote: "However, some Greek cities (which I assume you meant) ..."

Ian wrote: "However, some Greek cities (which I assume you meant) ..."[Grin!] Thank you for putting me back at the right section of the historical timeline, Ian!

I have been listening to the Great Courses sessions on The Foundations of Western Civilization and having conversations elsewhere on justice as applied to individuals versus justice in its institutional/communal aspects. That's where my thoughts were when I tried to pose an applicable question. One of the things that haunts is the tendency for points of significant imbalance in access to material resources to be vulnerable to social disruption. Returning to Aristotle, I shall try to understand how "distributive" and "corrective" justice relate to the individual versus to the community.

Lily wrote: "Ian wrote: "However, some Greek cities (which I assume you meant) ..."

Lily wrote: "Ian wrote: "However, some Greek cities (which I assume you meant) ..."[Grin!] Thank you for putting me back at the right section of the historical timeline, Ian!."

You're welcome.

I now think that I was misleadingly terse about the Romans, as I was just skipping over them to get back to the Greeks.

In Republican times the Romans did have a *practice* of distributing land to (mainly) veterans of the legions, but this was in conquered territory, and aimed at creating colonies of Roman citizens in "barbarian" (i.e., foreign) territory, and even so a lot of the "new" lands in Italy wound up the hands of the very rich.

During the Civil Wars which marked the collapse of the Republic, one side or the other would confiscate estates from opponents, and parcel them out among their "deserving" supporters.

There were earlier attempts at actual land redistribution, calling for taking recently-acquired lands from the rich, and giving them to the deserving peasants who had been displaced by the change-over from small farms to plantation agriculture. The proponents usually were promptly killed as dangerous radicals and subversives (well, that was the excuse), although even some conservative Romans recognized that the economic changes were undermining the Republic, and also endangering the source of troops for the Legions from families of citizen-farmers.

(My apologies to those already familiar with Roman history, who will see that I have omitted a whole lot of interesting and important details and qualifications.)

Thomas wrote: "Distributive justice is proportional. In chapter 3, justice between two parties is described as a four part ratio that demonstrates how much of the thing in question each party should receive, depending on their merits. If the people are not equal, they will not be treated equally. Does this make sense?"

Thomas wrote: "Distributive justice is proportional. In chapter 3, justice between two parties is described as a four part ratio that demonstrates how much of the thing in question each party should receive, depending on their merits. If the people are not equal, they will not be treated equally. Does this make sense?"A good example of when distributive justice, or proportional equality make sense are paychecks. Different jobs demand their own ranges of compensation. We expect a CEO in a big company/market to make proportionally more than the mail room staff in a smaller company/market and this seems fair and just to us. What does not seem just and fair to us are when certain other considerations such as race or gender come into play skewing the proportionality.

Thomas wrote: "How do laws fit into all this? Can laws apply generally when justice depends on the specific circumstances of a case and the relative merits of the parties involved?"

Thomas wrote: "How do laws fit into all this? Can laws apply generally when justice depends on the specific circumstances of a case and the relative merits of the parties involved?"Aristotle seems to acknowledge a difference between acts of legal justice (the law) and justice as virtuous acts, or acts of excellence:

[1130.20. . .for practically the majority of the acts commanded by the law are those which are prescribed from the point of view of excellence taken as a whole; for the law bids us practise every excellence and forbids us to practise any [25] vice. And the things that tend to produce excellence taken as a whole are those of the acts prescribed by the law which have been prescribed with a view to education for the common good. But with regard to the education of the individual as such, which makes him without qualification a good man, we must determine later whether this is the function of the political art or of another; for perhaps it is not the same in every case to be a good man and a good citizen.Practically the majority seems to be an acknowledgment that not all acts of law are either virtuously just or equal, proportionally or otherwise, but practically accepted as such because they are laws. Suggesting that a good man and a good citizen are not the same in every case is another way he acknowledges this.

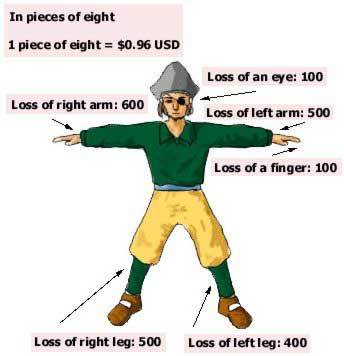

Another example of distributive justice :)

Another example of distributive justice :)

More on distributive pirate economics can be found here: http://freakonomics.com/2007/09/17/th...

David quoted Aristotle: " But with regard to the education of the individual as such, which makes him without qualification a good man, we must determine later whether this is the function of the political art or of another; for perhaps it is not the same in every case to be a good man and a good citizen."

David quoted Aristotle: " But with regard to the education of the individual as such, which makes him without qualification a good man, we must determine later whether this is the function of the political art or of another; for perhaps it is not the same in every case to be a good man and a good citizen."Practically the majority seems to be an acknowledgment that not all acts of law are either virtuously just or equal, proportionally or otherwise, but practically accepted as such because they are laws.."

The distinction between being a good man and being a good citizen seems to follow from the way that Aristotle analyzes the virtues of character as well. To be a good citizen, all one must do is follow the laws. To be a good man, one must be able to strike a variety of means that can't be arrived at by applying rules.

It is interesting then that justice seems to be highly formulated, even mathematical. Why is this so?

Thomas wrote: "It is interesting then that justice seems to be highly formulated, even mathematical. Why is this so?"

Thomas wrote: "It is interesting then that justice seems to be highly formulated, even mathematical. Why is this so?"I think it is because unlike the previous means and extremes of emotions Aristotle has discussed, which are messy and do not comply with mathematical formulas. Justice is not an emotion but an action involving fairness or equality of things that does often lend itself to enumerated equivalencies and mathematical formulas, e.g., equal pay for equal work, 2.4 acres for $50K, 500 pieces of eight for the loss of 1 right leg, vs. 400 for loss of 1 left leg.

Thomas wrote: "To be a good citizen, all one must do is follow the laws. To be a good man, one must be able to strike a variety of means that can't be arrived at by applying rules. "

Thomas wrote: "To be a good citizen, all one must do is follow the laws. To be a good man, one must be able to strike a variety of means that can't be arrived at by applying rules. "That is a very good point. I am having a hard time determining if Aristotle is acknowledging that some laws are bad or if laws simply do not, cannot, and should not apply to everything involving justice and in those areas where the law does not apply, the good man must transcend the lawful man to act justly.

This is not particular to Book Five, but Aristotle refers to the spendthrift man as "wasting his substance"- he actually uses the metaphysical term ouisia.. (sp?)- his being or essence. The medieval term was substantia- because it was the underlying being of which the elements derive.. although putting it that way already begs the question.

This is not particular to Book Five, but Aristotle refers to the spendthrift man as "wasting his substance"- he actually uses the metaphysical term ouisia.. (sp?)- his being or essence. The medieval term was substantia- because it was the underlying being of which the elements derive.. although putting it that way already begs the question.

Some additional remarks and questions on Book Five:

Some additional remarks and questions on Book Five:In addition to distributive and corrective justice there appears to be, in chapter 5, reciprocal justice. Like distributive justice, reciprocal justice is proportional because, according to Aristotle, not all men are equal, nor are the products of their work always commensurable. Reciprocity keeps the city together -- men in positions of authority are able to keep order because they have more power over others, and equitable exchange is possible in the marketplace via proportional exchanges of products and currency. Again, justice seems to be reduced to quantity.

Aristotle says that justice is a mean between "doing injustice and having injustice done to oneself, for the former is having a greater amount and the latter a lesser amount." Justice is a certain kind of mean condition, but it's not like the other virtues because it is concerned with a mean quantity. Why is justice different? The other virtues are done for "the beautiful" or "the noble." Why not justice as well?

In chapter 6, Aristotle mentions that just men sometimes commit unjust acts. He seems to be thinking of crimes of passion, or one-time acts of injustice. He goes on to discuss justice in the political life, compared to justice among those who have laws, and justice in the family. The argument is muddy here, but it seems to lead into the discussion of natural versus conventional law in chapter 7.

Chapter 8 covers justice and voluntariness. Basically, an action must be done willingly and knowingly in order to be just or unjust. Mistakes, accidents, negligent acts, and acts of passion are therefore exempt. Interestingly, Aristotle says that some acts done out of ignorance are forgivable, and others are not. How does forgiveness play into justice?

A. poses some interesting questions in chapter 9: Is it possible to suffer injustice willingly? Is it unjust to give more than is deserved? Is it possible to be unjust to oneself? Why do just men do unjust things? (Which requires us to understand how this is not a contradiction for Aristotle.)

What is "decency" and how does it differ from justice?

And finally... What is worse: to act unjustly, or to suffer injustice?

Christopher wrote: "This is not particular to Book Five, but Aristotle refers to the spendthrift man as "wasting his substance"- he actually uses the metaphysical term ouisia.. (sp?)- his being or essence. The medieva..."

Christopher wrote: "This is not particular to Book Five, but Aristotle refers to the spendthrift man as "wasting his substance"- he actually uses the metaphysical term ouisia.. (sp?)- his being or essence. The medieva..."Ousia in its original, ordinary sense meant personal property, but Plato and then Aristotle gave it a metaphysical meaning as well.

Joe Sachs glosses the word thusly in his translation of the Metaphysics: "In ordinary speech the word means wealth or inalienable property, the inherited state that cannot be taken away from one who is born with it. Punning on its connection with the participle of the verb 'to be', Plato appropriates the word (as at Meno 72b) to mean the very being of something, in respect to which all instances of it are exactly alike."

Cphe wrote: "So A is saying that you can be a bad citizen but also a good man - then how could you be considered moral?

Cphe wrote: "So A is saying that you can be a bad citizen but also a good man - then how could you be considered moral? ..."

The first example I thought of was Rosa Parks. According to the law and custom, there were probably a lot of people who thought she was a bad citizen at the time.

I thought A. was saying you could be a 'law-abiding citizen' and still not meet the HIGHER standard of a good person.

I thought A. was saying you could be a 'law-abiding citizen' and still not meet the HIGHER standard of a good person.Not bad citizen, but good person (although that is also a possibility), but good citizen, still not a good person.

This comes up in The Merchant of Venice. Shylock is legally entitled to his pound of flesh, but Portia says, "Then must the Jew be merciful."

PORTIA

Do you confess the bond?

ANTONIO

I do.

PORTIA

Then must the Jew be merciful.

SHYLOCK

On what compulsion must I? tell me that.

... And I beseech you,

... And I beseech you,Wrest once the law to your authority:

To do a great right, do a little wrong,

And curb this cruel devil of his will.

PORTIA

It must not be; there is no power in Venice

Can alter a decree established:

'Twill be recorded for a precedent,

And many an error by the same example

Will rush into the state: it cannot be.

Christopher wrote: "I thought A. was saying you could be a 'law-abiding citizen' and still not meet the HIGHER standard of a good person..."

Christopher wrote: "I thought A. was saying you could be a 'law-abiding citizen' and still not meet the HIGHER standard of a good person..."Ah--well, there I go again, jumping the gun. I've read a couple chapters into book five, but probably not far enough to comment yet.

Christopher wrote: "I thought Book Five was almost like going back to Book One, in terms of obscurity."

Christopher wrote: "I thought Book Five was almost like going back to Book One, in terms of obscurity."One wonders at times if some of these aren't Aristotle arguing with himself.

@6 David wrote: "A good example of when distributive justice, or proportional equality make sense are paychecks. Different jobs demand their own ranges of compensation. We expect a CEO in a big company/market to make proportionally more than the mail room staff in a smaller company/market and this seems fair and just to us......"

@6 David wrote: "A good example of when distributive justice, or proportional equality make sense are paychecks. Different jobs demand their own ranges of compensation. We expect a CEO in a big company/market to make proportionally more than the mail room staff in a smaller company/market and this seems fair and just to us......""In the UK, when asked what a typical British chief executive earned in comparison with an unskilled worker, people guessed 33 times as much. When asked what the ideal ratio should be, they said 7:1. Oxfam said that FTSE 100 bosses earned on average 120 times more than the average employee."

"Inequality Gap Widens as 42 People Hold Same Wealth as 37bn Poorest"

https://www.theguardian.com/inequalit...

Figures like these vary from study to study. Yet, they have been astounding for years.

Lily wrote: ""In the UK, when asked what a typical British chief executive earned in comparison with an unskilled worker, people guessed 33 times as much. When asked what the ideal ratio should be, they said 7:1. Oxfam said that FTSE 100 bosses earned on average 120 times more than the average employee."."

Lily wrote: ""In the UK, when asked what a typical British chief executive earned in comparison with an unskilled worker, people guessed 33 times as much. When asked what the ideal ratio should be, they said 7:1. Oxfam said that FTSE 100 bosses earned on average 120 times more than the average employee."."Which raises the question, "Is it possible to suffer injustice willingly?"

Thomas wrote: "Which raises the question, "Is it possible to suffer injustice willingly?"

Thomas wrote: "Which raises the question, "Is it possible to suffer injustice willingly?"Maybe not willingly, but begrudgingly? Doesn't Aristotle hedge his bet earlier by acknowledging the relativity of choices by explaining something about the lessor or two evils? I will try and give the Bekker numbers for this when I have time to go back and find it.

Thomas wrote: "Which raises the question, "Is it possible to suffer injustice willingly?",..."

Thomas wrote: "Which raises the question, "Is it possible to suffer injustice willingly?",..."Don't we all accept it regularly every time a speeding driver rudely (dangerously) cuts us off? (Grin-- and swear, if driving.) Or, put another way, doesn't living graciously often require tolerance for instances of injustice?

I finished reading book v this evening--I thought this was a difficult chapter to wrap my head around. At times, he either seemed to be explaining obvious things in a very circular way, or he was trying to make distinctions that were difficult to grab onto.

I finished reading book v this evening--I thought this was a difficult chapter to wrap my head around. At times, he either seemed to be explaining obvious things in a very circular way, or he was trying to make distinctions that were difficult to grab onto. I wonder if book v wouldn't have benefited from a chapter by chapter breakdown discussion.

It's also interesting (to me, anyway), that my copy must have been passed around between a couple of students--there is copious highlighting and underlining, and it's possible that three different people may have used it (though one could have lost her highlighter and switched to ink pen, I don't know). But what's interesting is that the highlighting (which nearly covers entire pages in some spots) is absent from book iv, v, and vi. It makes me wonder if the teacher said, 'look, I only have so much time here. Let's skip ahead to the juicy bits.'

Bryan wrote: "It's also interesting (to me, anyway), that my copy must have been passed around between a couple of students--there is copious highlighting and underlining, and it's possible that three different people may have used it (though one could have lost her highlighter and switched to ink pen, I don't know). But what's interesting is that the highlighting (which nearly covers entire pages in some spots) is absent from book iv, v, and vi. It makes me wonder if the teacher said, 'look, I only have so much time here. Let's skip ahead to the juicy bits.' "

Bryan wrote: "It's also interesting (to me, anyway), that my copy must have been passed around between a couple of students--there is copious highlighting and underlining, and it's possible that three different people may have used it (though one could have lost her highlighter and switched to ink pen, I don't know). But what's interesting is that the highlighting (which nearly covers entire pages in some spots) is absent from book iv, v, and vi. It makes me wonder if the teacher said, 'look, I only have so much time here. Let's skip ahead to the juicy bits.' "I wonder if they just read this book to compare Aristotle's notes on justice with what Plato had to say in The Republic?

I just finished reading it also. Now to the hard part of understanding it...

Genni wrote: "I wonder if they just read this book to compare Aristotle's notes on justice with what Plato had to say in The Republic?..."

Genni wrote: "I wonder if they just read this book to compare Aristotle's notes on justice with what Plato had to say in The Republic?..."I'm not sure--but these three books (iv, v and vi) were the only ones not highlighted. I was just wondering if (and why) the instructor might have thought that these were worth skipping. Too difficult for the class he was teaching? I know I found them difficult.

Bryan wrote: "Genni wrote: "I wonder if they just read this book to compare Aristotle's notes on justice with what Plato had to say in The Republic?..."

Bryan wrote: "Genni wrote: "I wonder if they just read this book to compare Aristotle's notes on justice with what Plato had to say in The Republic?..."I'm not sure--but these three books (iv, v and vi) were t..."

Oops. I misread your post. :-) I read that they were highlighted. My bad.

Thomas wrote: "Aristotle says that justice is a mean between "doing injustice and having injustice done to oneself, for the former is having a greater amount and the latter a lesser amount." Justice is a certain kind of mean condition, but it's not like the other virtues because it is concerned with a mean quantity. Why is justice different? The other virtues are done for "the beautiful" or "the noble." Why not justice as well?

Thomas wrote: "Aristotle says that justice is a mean between "doing injustice and having injustice done to oneself, for the former is having a greater amount and the latter a lesser amount." Justice is a certain kind of mean condition, but it's not like the other virtues because it is concerned with a mean quantity. Why is justice different? The other virtues are done for "the beautiful" or "the noble." Why not justice as well? "

Does he say that it is not for the beautiful or noble?

Thomas wrote: "And finally... What is worse: to act unjustly, or to suffer injustice? ."

Thomas wrote: "And finally... What is worse: to act unjustly, or to suffer injustice? ."Hi, Plato. Why must we choose? They are both equally bad.

Lily wrote: "Don't we all accept it regularly every time a speeding driver rudely (dangerously) cuts us off? (Grin-- and swear, if driving.) Or, put another way, doesn't living graciously often require tolerance for instances of injustice?"

Lily wrote: "Don't we all accept it regularly every time a speeding driver rudely (dangerously) cuts us off? (Grin-- and swear, if driving.) Or, put another way, doesn't living graciously often require tolerance for instances of injustice?"In cases where we have no choice but to accept injustice, we may do it graciously, or grudgingly, but not willingly. An example of willing injustice upon oneself might be taking less than one is worth. I had an economics teacher who returned his salary to the school as a donation, mostly because he was wealthy already and wanted to benefit the school. But he did it willingly and happily, even though he technically did an injustice to himself by refusing just compensation.

Bryan wrote: "But what's interesting is that the highlighting (which nearly covers entire pages in some spots) is absent from book iv, v, and vi. It makes me wonder if the teacher said, 'look, I only have so much time here. Let's skip ahead to the juicy bits.' "

Bryan wrote: "But what's interesting is that the highlighting (which nearly covers entire pages in some spots) is absent from book iv, v, and vi. It makes me wonder if the teacher said, 'look, I only have so much time here. Let's skip ahead to the juicy bits.' "Book 6 is one of the more interesting parts of the Ethics, in my opinion. I think a lot of what we've read so far, at least in books 3, 4, and 5, are surveys of popular opinion -- the "things that are known to us." Aristotle begins to move away from those things to the "things that are known in themselves" in Book 6.

But I have to agree that Book 5 is very choppy. I think Genni is probably right, that Aristotle was in many ways responding to the Republic. At least one scholar has argued that the Ethics was written with Plato very much in mind -- Aristotle's Dialogue with Socrates.

Genni wrote: "Does he say that it is not for the beautiful or noble? "

Genni wrote: "Does he say that it is not for the beautiful or noble? "Well, no. Do you think he just forgot to mention it? ; )

It just seems to me that Aristotle's treatment of justice is especially sloppy and haphazard -- not that we can conclude anything from this, but his analysis is far from beautiful in itself. Justice is a sort of necessary evil rather than something to aspire to. Like math homework.

Cphe wrote: "I wonder if during the depression many did not take an injustice. That is, taking what work available to feed their children.

Cphe wrote: "I wonder if during the depression many did not take an injustice. That is, taking what work available to feed their children. I suspect that quite a few in those circumstance might have been thoug..."

I've been reading "willing" as "wanting," and maybe that's too broad. No one wants to live during a depression and take whatever she can get, but we willingly do it if we have no choice. Without that choice, I have a hard time thinking of it as a willing decision. But if willing is read as simple intentionality, then willing injustice is something we do all the time.

It seemed to me that A. made a distinction about suffering injustice willingly in order for some other good to happen, and suffering injustice willingly simply for the sake of suffering injustice. If some other good was going to accrue because of the injustice, then that sort of canceled out the injustice of the situation. In his example, I believe he used a person who was divvying up some spoils--he might take a lesser portion because in the end he would gain more honor for it.

It seemed to me that A. made a distinction about suffering injustice willingly in order for some other good to happen, and suffering injustice willingly simply for the sake of suffering injustice. If some other good was going to accrue because of the injustice, then that sort of canceled out the injustice of the situation. In his example, I believe he used a person who was divvying up some spoils--he might take a lesser portion because in the end he would gain more honor for it. Still, A seems to shave these points exceedingly fine--if I understood at all what he was saying, most of his assertions in this chapter seem like mountainous molehills. But, then, who am I to argue with Aristotle? I'm keeping my fallback position of, 'I'm probably not understanding this correctly.'

When I read the EN a few years ago, I was also left with the "first impression" that Aristotle only spoke platitudes and conventional wisdom.

When I read the EN a few years ago, I was also left with the "first impression" that Aristotle only spoke platitudes and conventional wisdom.Now (this time) I understand a little better A's "scheme," but it's not like a whole new love of this book.

Thomas wrote: " Justice is a sort of necessary evil rather than something to aspire to. "

Thomas wrote: " Justice is a sort of necessary evil rather than something to aspire to. "Of course it would be amazing if we lived in a world where justice was not required, but even though justice is necessary, I don't think A sees it as something not to aspire to? The following comments come to mind:

"...justice is often thought to be the greatest of virtues, and 'neither evening nor morning star' is so wonderful; and proverbially 'in justice is every virtue comprehended'. And it is complete virtue in its fullest sense because it is the actual exercise of complete virtue." (somewhere between 1129b13 and 1130a6).

Although these comments were about "universal" justice rather than the more "particular" justice that he spent most of the book on, it seems to me that they can still be applied?

David wrote: "Thomas wrote: Which raises the question, "Is it possible to suffer injustice willingly?"

David wrote: "Thomas wrote: Which raises the question, "Is it possible to suffer injustice willingly?"Maybe not willingly, but begrudgingly? Doesn't Aristotle hedge his bet earlier by acknowledging the relativity of choices by explaining something about the lessor or two evils? I will try and give the Bekker numbers for this when I have time to go back and find it.."

Found it.

1131b.20. . .In the case of evil the reverse is true; for the lesser evil is reckoned a good in comparison with the greater evil, since the lesser evil is rather to be chosen than the greater, and what is worthy of choice is good, and what is worthier of choice a greater good. This, then, is one species of the just.Trolley problem, anyone?

Genni wrote: "

Genni wrote: "...justice is often thought to be the greatest of virtues, and 'neither evening nor morning star' is so wonderful; and proverbially 'in justice is every virtue comprehended'. And it is complete virtue in its fullest sense because it is the actual exercise of complete virtue." (somewhere between 1129b13 and 1130a6).."

Why does he say justice is often thought to be the greatest, and use proverbially, I wonder.

Sachs's note on the morning and evening star is also interesting:

In the same way that the phrases "morning star" and "evening star" have different meanings, but both refer to Venus, justice in this broad sense still does not mean the same thing as virtue, but it turns out to name it from a certain perspective.

It seems to me that Aristotle is examining justice from several angles without ever clarifying what it is in any singular sense. For example, what does it mean that a just man can do unjust things? There is an uncomfortable amount of ambiguity here and it runs throughout the chapter. It sounds almost like someone who is thinking aloud rather than moving systematically to a conclusion. (Or it could be that I simply haven't spent enough time trying to make sense of a fairly sketchy chapter of the book.)

David wrote: "David wrote: "Thomas wrote: Which raises the question, "Is it possible to suffer injustice willingly?"

David wrote: "David wrote: "Thomas wrote: Which raises the question, "Is it possible to suffer injustice willingly?"Maybe not willingly, but begrudgingly? Doesn't Aristotle hedge his bet earlier by acknowledgi..."

What do you think about Plato's Apology in this regard? Could we say that Socrates willingly suffered injustice, in his case, for the city?

Thomas wrote: "What do you think about Plato's Apology in this regard? Could we say that Socrates willingly suffered injustice, in his case, for the city?"

Thomas wrote: "What do you think about Plato's Apology in this regard? Could we say that Socrates willingly suffered injustice, in his case, for the city?"Since Socrates judged it more worthy to suffer his sentence than to accept aid in being smuggled away, then it seems to follow that Aristotle claims his execution as a species of justice.

what is worthy of choice is good, and what is worthier of choice a greater good. This, then, is one species of the just.I disagree that his execution was a more worthy choice. His death seems a legally suspicious and virtuously unjust waste of life and mind, willingly suffered and the world suffers from a life cut short.

Of course, there is the famous anecdote that Aristotle left Athens when he was accused like Socrates.

Of course, there is the famous anecdote that Aristotle left Athens when he was accused like Socrates.Diogenes Laertius says that the accusers of Socrates were later accused and put to death.

[43] So he was taken from among men; and not long afterwards the Athenians felt such remorse that they shut up the training grounds and gymnasia. They banished the other accusers but put Meletus to death; they honoured Socrates with a bronze statue, the work of Lysippus, which they placed in the hall of processions. And no sooner did Anytus visit Heraclea than the people of that town expelled him on that very day. Not only in the case of Socrates but in very many others the Athenians repented in this way.

http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/t...

Thomas wrote: "Why does he say justice is often thought to be the greatest, and use proverbially, I wonder. "

Thomas wrote: "Why does he say justice is often thought to be the greatest, and use proverbially, I wonder. "I have no idea about your other questions, and personally, similar to Bryan, I have found the whole work confusing, not just this book. But as to the above comment, Aristotle has shown that he has no qualms with disagreeing with anyone, even a well-beloved teacher. So when he says "it is thought" and "proverbially" and doesn't argue with it, I am taking it to mean that they are the closest expression of something he agrees with. But I'm curious if there is some nuance in the Greek that indicates otherwise?

Cphe wrote: "Question: Do you think that justice comes from within in part?...."

Cphe wrote: "Question: Do you think that justice comes from within in part?...."Interesting question, Cphe. I don't; I think of "justice" as how we treat each other. As for Aristotle, ...?

Then there is that enigmatic book of Job, while one is wrestling with what is justice. Especially when the "happy ending" is now viewed by many scholars as sort of tacked on.

I find myself at times wondering if understanding Aristotle might be better attained by reading the life of his pupil Alexander.

Lily wrote: "I find myself at times wondering if understanding Aristotle might be better attained by reading the life of his pupil Alexander."

Lily wrote: "I find myself at times wondering if understanding Aristotle might be better attained by reading the life of his pupil Alexander."An interesting suggestion: However, the the story of Aristotle as Alexander's tutor has been challenged in recent times. (Other scholars continue to accept it.)

The problem is that it only shows up in very late sources, like Diogenes Laertius' "Lives of the Philosophers" and Plutarch's "Life of Alexander."

Diogenes is untrustworthy in general, although he sometimes get things right, and for some things is our only source. (It has been argued that part of the problem may be that he was abstracting already condensed accounts from earlier handbooks, and passing on their misinformation, or garbling it.)

Plutarch seems a good bit more intellectually sophisticated than Diogenes, but doesn't seem to have spent much time pondering the reliability of a source for a good story. (Somewhat ironic since he did a hatchet-job on Herodotus, partly on the basis that he trusted untrustworthy sources....)

It *could* be true, and it would explain why Alexander dragged along a relative of Aristotle as tutor to his Macedonian pages, which caused a lot of trouble. But if that is factual, Aristotle as Alexander's teacher still could have been invented for just that explanation.

One of the things that counted against Aristotle in Athens was the fact that he had important Macedonians as friends, which does not confirm a connection with Alexander, but also allows for the possibility.

Aristotle-as-royal-tutor is still taken as fact in some of the contributions to the Blackwell A Companion to Ancient Macedonia (2010)

(I mentioned this problem as an aside, in message 20 for Book Three, so I doubt that anyone remembers it. If someone did, sorry for the repetition.)

Genni wrote: "I have no idea about your other questions, and personally, similar to Bryan, I have found the whole work confusing, not just this book. But as to the above comment, Aristotle has shown that he has no qualms with disagreeing with anyone, even a well-beloved teacher."

Genni wrote: "I have no idea about your other questions, and personally, similar to Bryan, I have found the whole work confusing, not just this book. But as to the above comment, Aristotle has shown that he has no qualms with disagreeing with anyone, even a well-beloved teacher."Well, at least we can all keep each other company in our confusion. I find no simple way out of it, but for now I'm going with this: Aristotle is presenting multiple points of view of justice, all of which have some validity but none of which is definitive.

One of Aristotle's favorite phrases is "in a certain way." He loves to make distinctions, pry things apart, and find out what things are in themselves. And he always starts with the commonplace, because there is often something true about popular opinion, even though it is usually imprecise and needs a good cleaning up.

It looks to me like he is examining the way we think and talk about virtue the way he might dissect an animal, in order to find out what's inside. He isn't quite sure what he's looking at. Some of the parts don't have names. But he can see how different parts are distinct from each other, and each has its place and function. How it all fits together isn't so clear though.

Genni wrote: "So when he says "it is thought" and "proverbially" and doesn't argue with it, I am taking it to mean that they are the closest expression of something he agrees with. But I'm curious if there is some nuance in the Greek that indicates otherwise? "

Genni wrote: "So when he says "it is thought" and "proverbially" and doesn't argue with it, I am taking it to mean that they are the closest expression of something he agrees with. But I'm curious if there is some nuance in the Greek that indicates otherwise? "I saw something after looking at this passage again which might help. Or might not. :/ (....yes, this is bugging me.)

It looks like what he is referring to is general justice, which is "complete virtue" in regards to others. It is aimed at the political community, and it isn't what we normally think of as justice. We don't normally think of being just toward our country when we sign up for military service -- we think of being patriotic or something. We don't think of giving alms to the poor as political justice -- we normally think of it as generosity. For Aristotle it looks like all these things fall under the umbrella of justice as "complete virtue." (It sounds like only the great-souled person could be truly just in this sense, inasmuch as it incorporates all the virtues.)

He then makes a distinction about particular forms of justice, which have to do with the giving and taking of things (money, property, honor, responsibility, blame) in the correct measure. I think this is closer to our common, conventional sense of justice.

Thomas wrote: "One of Aristotle's favorite phrases is "in a certain way." He loves to make distinctions, pry things apart, and find out what things are in themselves. And he always starts with the commonplace, because there is often something true about popular opinion, even though it is usually imprecise and needs a good cleaning up. "

Thomas wrote: "One of Aristotle's favorite phrases is "in a certain way." He loves to make distinctions, pry things apart, and find out what things are in themselves. And he always starts with the commonplace, because there is often something true about popular opinion, even though it is usually imprecise and needs a good cleaning up. "I like the way you look at it. And it seems that Aristotle's mean (as well as his ambiguous ideas about justice) have infiltrated society and become commonplace and popular opinion in themselves...

Thomas wrote: "It looks like what he is referring to is general justice, which is "complete virtue" in regards to others. It is aimed at the political community, and it isn't what we normally think of as justice. We don't normally think of being just toward our country when we sign up for military service -- we think of being patriotic or something. We don't think of giving alms to the poor as political justice -- we normally think of it as generosity. For Aristotle it looks like all these things fall under the umbrella of justice as "complete virtue." (It sounds like only the great-souled person could be truly just in this sense, inasmuch as it incorporates all the virtues.)

Thomas wrote: "It looks like what he is referring to is general justice, which is "complete virtue" in regards to others. It is aimed at the political community, and it isn't what we normally think of as justice. We don't normally think of being just toward our country when we sign up for military service -- we think of being patriotic or something. We don't think of giving alms to the poor as political justice -- we normally think of it as generosity. For Aristotle it looks like all these things fall under the umbrella of justice as "complete virtue." (It sounds like only the great-souled person could be truly just in this sense, inasmuch as it incorporates all the virtues.) He then makes a distinction about particular forms of justice, which have to do with the giving and taking of things (money, property, honor, responsibility, blame) in the correct measure. I think this is closer to our common, conventional sense of justice.."

I'm sorry, Thomas, I don't follow. Just because those things don't immediately pop up in the mind in connection with justice doesn't mean that they don't fulfill a role of justice (although it may not be the complete role), right? And the particular forms of justice seem to me to fall under the "umbrella of justice". I mean, they often have just as much to do with neighbor and political community, no????

Genni wrote: "I'm sorry, Thomas, I don't follow. Just because those things don't immediately pop up in the mind in connection with justice doesn't mean that they don't fulfill a role of justice (although it may not be the complete role), right? "

Genni wrote: "I'm sorry, Thomas, I don't follow. Just because those things don't immediately pop up in the mind in connection with justice doesn't mean that they don't fulfill a role of justice (although it may not be the complete role), right? "My understanding of 5.1 is that justice as a "complete virtue" is with regard to the political community. Otherwise he could just call it "complete virtue" or great-souledness, as he has before. Maybe he makes this distinction because it's not what we normally think of as justice, though I guess you can say that every virtue involves the political community and is therefore a sort of justice. Nevertheless, he makes a distinction.

I'm trying to interpret what he's saying in 5.2, where he talks about "the sort of justice that is present in a part of virtue, for there is one, as we assert." In 5.1 he discusses the sort of justice that is a "complete virtue," which includes all the other virtues of character-- those things that I don't think of as being a part of justice normally. He's making a distinction in 5.2. He separates the general form of justice (which is equivalent to "complete virtue") from the particular forms, which involve taking more than one's share. Why does he treat this particular form of justice separately? My suspicion is that it's because this, the particular form that deals with equitable treatment, is what we think of when we think of justice, but I'm not sure. In any case, it takes up the rest of Book 5.

Books mentioned in this topic

A Companion to Ancient Macedonia (other topics)Aristotle's Dialogue with Socrates (other topics)

The Republic (other topics)

The Foundations of Western Civilization (other topics)

To start, Aristotle asks us to consider what justice is a mean between. If justice is a mean, what lies on either side of it? He seems to deal with justice in largely quantitative terms; this allows him to perform a mathematical analysis. Is this a sound approach? Is justice quantifiable?

He says that justice, like other virtues, is a "hexis", an "active condition," or disposition, or characteristic. He says that "active conditions are often discerned from those in whom they are present, for if being in good shape is something evident, then also being in bad shape becomes evident, and being in good shape is evident from those who are in good shape..." (1129a20) Does this mean that justice is self-evident? That we don't need to ask what it is... we can just see it?

There appear to be two categories of justice: distributive justice (involved in the distributions of honor or money), and corrective justice (involved in setting matters straight when someone has been wronged.) Distributive justice is proportional. In chapter 3, justice between two parties is described as a four part ratio that demonstrates how much of the thing in question each party should receive, depending on their merits. If the people are not equal, they will not be treated equally. Does this make sense?

Corrective justice is simpler, but Aristotle still uses a mathematical analysis. Instead of a ratio, this kind of justice is meted out by a judge who evens things up arithmetically, rather than proportionally. It still requires quantification, at least in Aristotle's analysis. How do we quantify an injury, or to use Aristotle's example, a wound unjustly inflicted?

How do laws fit into all this? Can laws apply generally when justice depends on the specific circumstances of a case and the relative merits of the parties involved?