The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

The Pickwick Papers

The Pickwick Papers

>

PP, Chp. 01-02

The second chapter already gives us the first adventure of Mr Pickwick and his three companions, and it also throws them in with a character who will appear every now and then throughout the pages of a rather picaresque novel, where most of “the characters come and go like the men and women we encounter in the real world”, as Dickens says in his preface to the 1837 edition.

WHAT HAPPENS

Mr Pickwick leaves his house on 13 May 1827 and takes a cab to the coach-stand at St. Martin’s-le-Grand. Due to his curiosity and his habit of writing the coachman’s answers down in a notebook, at the end of the trip, the coachman suspects Mr Pickwick (and his friends, who meet him at St. Martin’s-le-Grand) of being informers. [Note: The Victorian law system did not know any public prosecutor, and so crimes could only be prosecuted if somebody reported them to the authorities, the informer not necessarily having to be the victim of a crime. Since informers were often encouraged by being paid money for their troubles, this gave rise to professional informers – like Noah Claypole from Oliver Twist] In his ire, the coachman attacks Mr Pickwick, who is only rescued by the intervention of a shabby-genteel looking man by the name of Alfred Jingle, who, through his glib, and rather telegraphic, talk, saves the day for the Pickwickians. Finding out that their champion wants to go to Rochester, like themselves, Mr Pickwick offers Mr Jingle to travel together, and during the journey Mr Jingle’s talk worms himself into their confidence.

In Rochester, they soon order drinks and while Mr Pickwick, Mr Snodgrass and Mr Winkle soon drift into slumber, Mr Tupman is only roused by the alcohol – and by Mr Jingle’s references to the beauty of the Kentish women, as well as by those to a ball at the Bull Inn. Mr Tupman then decides to visit the ball in the company of Jingle, whom he dresses in Mr Winkle’s brand-new bright-blue dress-coat, which bears the sign of the Pickwick Club – something he can do very easily, with Mr Winkle being fast asleep – and they go to the ball. Once there, Mr Jingle causes trouble by successfully cutting out Dr Slammer, surgeon to the 97th, with a wealthy widow he is courting. Dr Slammer demands satisfaction but Mr Jingle just provokes him the more and ignores the challenge to a duel.

The next morning, Mr Winkle is called on by the doctor’s second, a Lieutenant Tappleton – Winkle was identified as the owner of the coat –, and since Mr Winkle cannot really remember the events of the preceding night too clearly, he thinks that he may well have slighted the doctor and that writing an apology would ruin his reputation as a sportsman. So he ensures himself of his friend Snodgrass as a second, although he is frightened to death of the encounter, and thinking that he may best induce the young poet into telling Mr Pickwick about the planned duel by entreating him to secrecy, he entreats him to secrecy. Unluckily, Mr Snodgrass takes his vow of silence seriously, and so the two Pickwickians go to the place assigned for the duel at the appointed time.

Luckily, Dr Slammer realizes that his friend has got him the wrong man, and the duel is called off, much to the chagrin of the surgeon Dr Payne, who tries his best to point out to the men present their respective rights to fighting a duel, but in vain. Relieved at neither having to fight nor being exposed as a poltroon, Mr Winkle invites the military men to visit them at the Bull Inn and make the acquaintance of Mr Pickwick and their other friends.

REMARKS

We can see very well how cleverly Dickens manages to meet the demands of instalment publication: On the one hand, the events described in Chapter 2 are brought to a certain close – i.e. the misunderstanding is cleared up –, but at the same time the chapter ends with a cliff-hanger in that we are asking ourselves what will happen when Dr Slammer follows the invitation, as he declares himself willing to do, and recognizes Mr Tupman and Mr Jingle. Will there be a duel after all? Will the association with Mr Jingle mean trouble for our hero Mr Pickwick?

Mr Jingle is clearly a very shady and underhanded character. He cuts the doctor out merely because he has a mind of doing it, and he also shows little respect for Mr Tupman and the Pickwick Emblem, guessing that P.C. means “peculiar coat”. At the same time, he is very imaginative and full of stories, tall stories mostly. Some of them are actually very cruel, like this one:

It is also quite strange that none of the Pickwickians realize what a down-on-his-luck fellow Jingle actually is. It is quite clear that he owns no more than what the shirt on his back (plus the one he carries in his pocket, wrapped up in a parcel), and yet he is believed by them when he tells them that his luggage is transported by vessel because it is so bulky. What does this tell you about Mr Pickwick?

Nice quotation:

This enables us to understand why Dr Slammer is so angry at finding the stranger coming between himself and the rich widow.

In my Penguin edition’s notes to Chapter 2, it is also said that Seymour first drew Mr Pickwick as a thin man, having the sporting motif in mind, which was soon discarded by Dickens, who said that he was not much of a sportsman and could therefore not supply a lot of knowledge in that field to the writing of such a story. Mr Winkle, in fact, is the only remnant of the sporting motif left in Pickwick as we have come to know it.

QUESTIONS

What do you think of how Dickens manages to give a short characterization of each of the Pickwickians in this second chapter?

After our first round through Dickens, especially with his later novels so fresh in mind, how do the first chapters of The Pickwick Papers appeal to you?

WHAT HAPPENS

Mr Pickwick leaves his house on 13 May 1827 and takes a cab to the coach-stand at St. Martin’s-le-Grand. Due to his curiosity and his habit of writing the coachman’s answers down in a notebook, at the end of the trip, the coachman suspects Mr Pickwick (and his friends, who meet him at St. Martin’s-le-Grand) of being informers. [Note: The Victorian law system did not know any public prosecutor, and so crimes could only be prosecuted if somebody reported them to the authorities, the informer not necessarily having to be the victim of a crime. Since informers were often encouraged by being paid money for their troubles, this gave rise to professional informers – like Noah Claypole from Oliver Twist] In his ire, the coachman attacks Mr Pickwick, who is only rescued by the intervention of a shabby-genteel looking man by the name of Alfred Jingle, who, through his glib, and rather telegraphic, talk, saves the day for the Pickwickians. Finding out that their champion wants to go to Rochester, like themselves, Mr Pickwick offers Mr Jingle to travel together, and during the journey Mr Jingle’s talk worms himself into their confidence.

In Rochester, they soon order drinks and while Mr Pickwick, Mr Snodgrass and Mr Winkle soon drift into slumber, Mr Tupman is only roused by the alcohol – and by Mr Jingle’s references to the beauty of the Kentish women, as well as by those to a ball at the Bull Inn. Mr Tupman then decides to visit the ball in the company of Jingle, whom he dresses in Mr Winkle’s brand-new bright-blue dress-coat, which bears the sign of the Pickwick Club – something he can do very easily, with Mr Winkle being fast asleep – and they go to the ball. Once there, Mr Jingle causes trouble by successfully cutting out Dr Slammer, surgeon to the 97th, with a wealthy widow he is courting. Dr Slammer demands satisfaction but Mr Jingle just provokes him the more and ignores the challenge to a duel.

The next morning, Mr Winkle is called on by the doctor’s second, a Lieutenant Tappleton – Winkle was identified as the owner of the coat –, and since Mr Winkle cannot really remember the events of the preceding night too clearly, he thinks that he may well have slighted the doctor and that writing an apology would ruin his reputation as a sportsman. So he ensures himself of his friend Snodgrass as a second, although he is frightened to death of the encounter, and thinking that he may best induce the young poet into telling Mr Pickwick about the planned duel by entreating him to secrecy, he entreats him to secrecy. Unluckily, Mr Snodgrass takes his vow of silence seriously, and so the two Pickwickians go to the place assigned for the duel at the appointed time.

Luckily, Dr Slammer realizes that his friend has got him the wrong man, and the duel is called off, much to the chagrin of the surgeon Dr Payne, who tries his best to point out to the men present their respective rights to fighting a duel, but in vain. Relieved at neither having to fight nor being exposed as a poltroon, Mr Winkle invites the military men to visit them at the Bull Inn and make the acquaintance of Mr Pickwick and their other friends.

REMARKS

We can see very well how cleverly Dickens manages to meet the demands of instalment publication: On the one hand, the events described in Chapter 2 are brought to a certain close – i.e. the misunderstanding is cleared up –, but at the same time the chapter ends with a cliff-hanger in that we are asking ourselves what will happen when Dr Slammer follows the invitation, as he declares himself willing to do, and recognizes Mr Tupman and Mr Jingle. Will there be a duel after all? Will the association with Mr Jingle mean trouble for our hero Mr Pickwick?

Mr Jingle is clearly a very shady and underhanded character. He cuts the doctor out merely because he has a mind of doing it, and he also shows little respect for Mr Tupman and the Pickwick Emblem, guessing that P.C. means “peculiar coat”. At the same time, he is very imaginative and full of stories, tall stories mostly. Some of them are actually very cruel, like this one:

”‘Heads, heads—take care of your heads!’ cried the loquacious stranger, as they came out under the low archway, which in those days formed the entrance to the coach-yard. ‘Terrible place—dangerous work—other day—five children—mother—tall lady, eating sandwiches—forgot the arch—crash—knock—children look round—mother’s head off—sandwich in her hand—no mouth to put it in—head of a family off—shocking, shocking! Looking at Whitehall, sir?—fine place—little window—somebody else’s head off there, eh, sir?—he didn’t keep a sharp look-out enough either—eh, Sir, eh?’”

It is also quite strange that none of the Pickwickians realize what a down-on-his-luck fellow Jingle actually is. It is quite clear that he owns no more than what the shirt on his back (plus the one he carries in his pocket, wrapped up in a parcel), and yet he is believed by them when he tells them that his luggage is transported by vessel because it is so bulky. What does this tell you about Mr Pickwick?

Nice quotation:

”he was indefatigable in paying the most unremitting and devoted attention to a little old widow, whose rich dress and profusion of ornament bespoke her a most desirable addition to a limited income.”

This enables us to understand why Dr Slammer is so angry at finding the stranger coming between himself and the rich widow.

In my Penguin edition’s notes to Chapter 2, it is also said that Seymour first drew Mr Pickwick as a thin man, having the sporting motif in mind, which was soon discarded by Dickens, who said that he was not much of a sportsman and could therefore not supply a lot of knowledge in that field to the writing of such a story. Mr Winkle, in fact, is the only remnant of the sporting motif left in Pickwick as we have come to know it.

QUESTIONS

What do you think of how Dickens manages to give a short characterization of each of the Pickwickians in this second chapter?

After our first round through Dickens, especially with his later novels so fresh in mind, how do the first chapters of The Pickwick Papers appeal to you?

Hi Tristram, and fellow Curiosities. This is my first time with Pickwick, and I am wondering.....it seems that the Club was in existence before Pickwick et al set off on their travels. Do we know, or do find out later, how the club came to exist, and why it is named after Mr P, rather than any of the others?

Hi Tristram, and fellow Curiosities. This is my first time with Pickwick, and I am wondering.....it seems that the Club was in existence before Pickwick et al set off on their travels. Do we know, or do find out later, how the club came to exist, and why it is named after Mr P, rather than any of the others?

I like this "PIckwickian sense." How does Mr. Blotton mean it? Obviously everyone, including Pickwick, finds this description acceptable, and a confrontation is avoided. (Of course the entire first chapter is a description of a pompous group of older men.) Pickwick seems to think of himself as an important observer of nature -- Tittlebats, indeed -- while in reality he is possibly clueless as to what transpires around him (chapter 2). So what does Mr. Blotton mean by "Pickwickian sense": tedious, irrelevant, foolish; or jovial, harmless, eccentric?

I like this "PIckwickian sense." How does Mr. Blotton mean it? Obviously everyone, including Pickwick, finds this description acceptable, and a confrontation is avoided. (Of course the entire first chapter is a description of a pompous group of older men.) Pickwick seems to think of himself as an important observer of nature -- Tittlebats, indeed -- while in reality he is possibly clueless as to what transpires around him (chapter 2). So what does Mr. Blotton mean by "Pickwickian sense": tedious, irrelevant, foolish; or jovial, harmless, eccentric?Dickens is a master of the long sentence. There are a few here a lesser writer would have lost himself in. Send in the first responders.

I always understood "meaning something in the Pickwickian sense" as "meaning something in a way that is not meant to give offense", i.e. not in the sense the word in question is usually understood.

I think Mr. Blotton was called on to take back his fervent expressions but he could not do so without, so he thought, losing face, and that's why he used this loophole of meaning the expression in the Pickwickian sense. It's probably not the first time that a probable conflict in the Pickwick Club was avoided that way.

As to the precedents of the Pickwick Club, Lagullande, I don't think we are given any information. The Pickwickians are simply there, and not accounted for ;-)

I think Mr. Blotton was called on to take back his fervent expressions but he could not do so without, so he thought, losing face, and that's why he used this loophole of meaning the expression in the Pickwickian sense. It's probably not the first time that a probable conflict in the Pickwick Club was avoided that way.

As to the precedents of the Pickwick Club, Lagullande, I don't think we are given any information. The Pickwickians are simply there, and not accounted for ;-)

Tristram wrote: "After our first round through Dickens, especially with his later novels so fresh in mind, how do the first chapters of The Pickwick Papers appeal to you?..."

Tristram wrote: "After our first round through Dickens, especially with his later novels so fresh in mind, how do the first chapters of The Pickwick Papers appeal to you?...""Pickwick" is like a breath of fresh air to me; Dickens doesn't take himself, his story, or his characters too seriously, and yet his affection for them shines through. The dilemmas are light - almost ridiculous, and fun. How can we fear for Mr. Winkle when we find ourselves chuckling at his strategy of reverse psychology in getting Mr. Snodgrass to report the duel to someone who might stop it? There's a certain screwball comedy element to it -- I can picture an "Arsenic and Old Lace" era Cary Grant getting tangled up with the Pickwick Club. In fact, he might make a wonderful Mr. Jingle (who, I believe, is as yet unnamed).

Pickwick, a thin man? Unthinkable! For me, Pickwick is the most recognizable of Dickens' characters. A thin, athletic Pickwick would never do! The contradiction between his reputation and his physical appearance is symbolic of the, well... Pickwickian nature of the book as a whole.

Now I know where the phrase "in the Pickwickian sense" comes from that Tristram uses from time to time! Not that I didn't know what book it came from, of course, but now I've experienced the actual scene. What a hoot!

Now I know where the phrase "in the Pickwickian sense" comes from that Tristram uses from time to time! Not that I didn't know what book it came from, of course, but now I've experienced the actual scene. What a hoot!Mary Lou - I'm also finding "Pickwick" a breath of fresh air. The characters are great and I can imagine them all figuring out how to proceed through their individual dilemmas. And yes, I couldn't help but chuckled at Mr. Winkle's attempt at reverse psychology. :)

I guess my big question at this point is, I'm not quite sure what the "point" of the Pickwick Club is? Did I miss what the aim and goals of the club is?

Tristram wrote: "Dear Curiosities,

Tristram wrote: "Dear Curiosities,Another year has started, and this time, after five years, we are once again at the beginning of our tour through Dickens’s novels, and it is therefore with great joy and expecta..."

I don't think I've ever read anything by Dickens that transitions effortlessly from serious to outright hilarity as we read Chapters 1 & 2, Tristram. In The Pickwickians , Dickens creates this atmosphere of an utmost serious nature by giving us a glimpse into the minutes of the club, and an introduction to the main player- a Mr. Samuel Pickwick, Esq., G.C.M.P.C; then, the additional contribution made by the "casual observer," adds a lighter flair. It deepened my understanding into the dynamics of the room revolving around Mr. Pickwick, but mostly gave me insight into the workings of this most illustrious character! To use Dickens's own words, the casual observer says, the sight was indeed an interesting one. HA! The transition slowly begins, giving us some light comedic fun. To then read,

And how much more interesting did the spectacle become, when, starting into full life and animation, as a simultaneous call for 'Pickwick' burst from his followers, that illustrious man slowly mounted into the Windsor chair, on which he had been previously seated, and addressed the club himself had founded,I found myself loving this moment, and all the pomp and circumstance associated with it.

The Pickwickians also brings to light Dickens's detail to appearance, the clothing and accoutrement of the characters, the distinctions in society that clothing creates. Beginning with, Mr. Pickwick...

his elevated position revealing those tights and gaiters, which, had they clothed an ordinary man, might have passed without observation, but which, when Pickwick clothed them-if we may use the expression-inspired involuntary awe and respect;moving on to Mr. Tupman where,

Time and feeding had expanded that once romantic form; the black waistcoat had become more an more developed; inch by inch had the gold watch-chain beneath it disappeared from within the range of Tupman's vision; and gradually the capacious chin encroached upon the borders of the white cravat...And lastly, for this chapter anyway, we have a Mr. Winkle, who

...poetically enveloped in a mysterious blue cloak with a canine-skin collar, and the latter communicating additional lustre to anew green shooting-coat, plaid neckerchief, and closely-fitted drabs.I bring these details up now because it does continue into the next chapter, and very well may continue throughout our reading, because it does address a common Dickens theme in the making, but also due to the timing of events. Pickwick says, Great men are seldom over scrupulous in the arrangement of their attire, while dressing himself and packing for the journey...This is followed by an exchange with someone who Dickens describes as

a strange specimen of human race, in a sackcloth coat, and apron of the same, who, with a brass label and number round his neck, looked as if he were catalogued in some collection of rarities. I found it curious for Pickwick to say what he does, and to then have our next visual of him observing someone to whom he could not possibly be referring.

The first ray of light which illumines the gloom, and converts into a dazzling brilliancy that obscurity in which the earlier history of the public career of the immortal Pickwick would appear to be involved...After reading these chapters, the very first sentence of the novel makes a lot more sense as to the course of events we have already been made aware and what is to come...It describes that progression from heavy to light I wrote about earlier. I look forward to reading how this novel unfolds, but so far, I'm thoroughly enjoying it right off the bat.

After our first round through Dickens, especially with his later novels so fresh in mind, how do the first chapters of The Pickwick Papers appeal to you?

Having just read "OMF," and "TMoED," with the group, isn't it noticeably obvious Dickens's vigor and joie de vivre in this first novel of his...So far? It's a breath of fresh air, Tristram, compared to the last two. In this current cycle of reading, I already feel as if I'm better equipped to draw upon the parallels to the spirit of his life

As an aside...Happy New Year to you Mods, and our tried and true members...It is a fantastic feeling for me to start this journey with you as we read The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club .

Tristram wrote: "The second chapter already gives us the first adventure of Mr Pickwick and his three companions, and it also throws them in with a character who will appear every now and then throughout the pages ..."

Tristram wrote: "The second chapter already gives us the first adventure of Mr Pickwick and his three companions, and it also throws them in with a character who will appear every now and then throughout the pages ..."In his ire, the coachman attacks Mr Pickwick, who is only rescued by the intervention of a shabby-genteel looking man by the name of Alfred Jingle, who, through his glib, and rather telegraphic, talk, saves the day for the Pickwickians.

Tristram, where was Mr. Jingle's name revealed? I missed this detail. I am completely excited about this character and have been most curious to find out who "exactly" he is; but the last reference I had to his name was when Tupman and he were making their way into the ball, and they were asked for their names...To which the stranger retorts, No names at all. I was also wondering, all throughout the ball, how these two men had spent so much time together without Tupman knowing this man's name. So funny!

Tristram wrote: "Dear Curiosities,

Tristram wrote: "Dear Curiosities,Another year has started, and this time, after five years, we are once again at the beginning of our tour through Dickens’s novels, and it is therefore with great joy and expecta..."

"I remember an early Dickens piece called The Mudfog Papers where he had imitated the style of minute-writing before, and it surely has its limitations because on most meetings where minutes are written nothing interesting ever happens."

I had to read a lot of meeting minutes for a research project last year and found them fascinating because the opposite was true: this was a series of very contentious public hearings and sometimes the minute reader would say something like "Mr. Smith expressed his support for property rights" when in fact Mr. Smith had threatened to take up arms if he didn't get his well permit (welcome to the enduring Wild West, folks). The minute writer was something of a master of understatement.

But these real-life minutes were only comical because I had the actual meeting to compare them to. I agree that Dickens seems to find himself stymied pretty fast by the limits of the form.

That said, the minutes still seem to be used effectively as foreshadowing for Chapter 2. Do I have it right that one of the reasons Mr. Blotton is willing to back off, when given the excuse, is that if he doesn't pull back from an insult he's getting into potential settle-it-with-a-duel territory himself? Calling his expression Pickwickian is, as Tristram points out, face-saving, and stops an escalation process that doesn't get stopped (until much later in the event) in the following chapter. This setting-up of Ch 2 in Ch 1 does underscore how easily the whole installment will slide between farce and mortal danger.

May I add also how much I love everything about the opening to Chapter 2: the description of the sun, and Mr. Pickwick as the sun, and his reflections on Goswell Street. And then just as I'm thinking how lovely it all is, Dickens steps in and calls it satirically "this beautiful reflection" and I feel like he's kind of making fun of me, too, because I fell for it hook, line, and sinker (and remain fallen)--but he isn't going to let me rest on that, is he? This is an opening that keeps you on your toes.

Tristram wrote: "The second chapter already gives us the first adventure of Mr Pickwick and his three companions, and it also throws them in with a character who will appear every now and then throughout the pages ..."

Tristram wrote: "The second chapter already gives us the first adventure of Mr Pickwick and his three companions, and it also throws them in with a character who will appear every now and then throughout the pages ..."I loved this whole chapter...I was smiling and laughing throughout the whole damned thing. The detail with which Dickens characterizes the stranger, both in his physical appearance,

The green coat had been a smart dress garment in the days of swallow-tails, but had evidently in those times adorned a much shorter man than the stranger, for the soiled and faded sleeves scarcely reached to his wrists. It was buttoned closely up to his chin, at the imminent hazard of splitting the back; and an old stock, without a vestige of shirt collar, ornamented his neck. His scanty black trousers displayed here and there those shiny patches which bespeak long service, and were strapped very tightly over a pair of patched and mended shoes, as if to conceal the dirty white stockings, which were nevertheless distinctly visible. His long, black hair escaped in negligent waves from beneath each side of his old pinched-up hat; and glimpses of his bare wrists might be observed between the tops of his gloves and the cuffs of his coat sleeves. His face was thin and haggard; but an indescribable air of jaunty impudence and perfect self-possession pervaded the whole man...And the man's acumen comparable to a well-travleled, lover of many women and a poet to boot, Dickens creates an irony between the external and internal of this strange man. This stranger in a green coat, is definitely a force to be reckoned with sitting amongst these three educated and well-versed in their individual specialties, his language and form of speaking, as you have mentioned, is worth reading alone...What a great character, he adds such great humor to these pages, which in my eyes seems to distract from details relating to his more...Disturbing characteristics?

Dickens hasn't served up this much comic relief... in spoon fulls...in one chapter, in anything that "I" have read thus far! It's really quite refreshing, this novel. A few of these moments I made notes for...

nothing like raw beef-steak for a bruise, sir; cold lamp-post very good, but lamp-post inconvenient-damned odd standing in the open street half an hour, with your eye against a lamp-post-eh...The story about the dog who wouldn't move because he was

transfixed -staring at a board-looking up, saw an inscription-Gamekeeper has order to shoot all dogs found in this inclosure-wouldn't pass it-woderful dog-valuable dog that-very;or even the tale of his Spanish conquest, who met her end due to the stomach pump? It's not even so much so, the stories that are laughable, but the impact of them on the three Pickwickians, that is noteworthy. Speaking of, I'm at a loss as to the details of this story... From what exactly did she die?

Oh, goodness, the duel too...From its genesis to its conclusion, and the course of events in between, was rib-tickling. I too am most compelled by what will transpire at the gathering in the next chapter.

It is quite clear that he owns no more than what the shirt on his back (plus the one he carries in his pocket, wrapped up in a parcel), and yet he is believed by them when he tells them that his luggage is transported by vessel because it is so bulky.

I did wonder why, yes, Tristram, as to the checked in portmanteau and hand held paper bag with a single shirt in it...But I too, failed to realize the true irony here.

What does this tell you about Mr Pickwick?

Perhaps, in spite of all his accolades and societal stature, that he may not be nearly astute as he may think himself, or others think him to be? However, I do find him to be continuously learning man...Open to understanding what he does not know.

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "After our first round through Dickens, especially with his later novels so fresh in mind, how do the first chapters of The Pickwick Papers appeal to you?..."

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "After our first round through Dickens, especially with his later novels so fresh in mind, how do the first chapters of The Pickwick Papers appeal to you?...""Pickwick" is like a ..."

The dilemmas are light - almost ridiculous, and fun. How can we fear for Mr. Winkle when we find ourselves chuckling at his strategy of reverse psychology in getting Mr. Snodgrass to report the duel to someone who might stop it? There's a certain screwball comedy element to it

Thank you for bringing this detail up about the reverse psychology attempted by Mr. Winkle on Mr. Snodgrass. Too funny. The visuals created in my mind by Dickens in most of Chapters 1 & 2, leaves me feeling that my impression of Dickens, as a master of his art, is not far-fetched.

Tristram wrote: "...to those who knew that the gigantic brain of Pickwick was working beneath that forehead, and that the beaming eyes of Pickwick were twinkling behind those glasses, the sight was indeed an interesting one. ..."

If this is the Secretary's view of Pickwick, one must question how accurate the minutes of the meeting were.

If this is the Secretary's view of Pickwick, one must question how accurate the minutes of the meeting were.

Tristram wrote: "Dr Slammer demands satisfaction but Mr Jingle just provokes him the more and ignores the challenge to a duel...."

I wondered whether dueling was still practiced when Pickwick was published. What I have been able to find is that it was dying out in the 1830s, but was still practiced, so there is a real possibility of danger to Mr. Jingle, if he can't get out of the challenge.

According to the Wikipedia entry on the Duke of Wellington, who became prime minister in 1828, "The Earl of Winchilsea accused the Duke of "an insidious design for the infringement of our liberties and the introduction of Popery into every department of the State".[163] Wellington responded by immediately challenging Winchilsea to a duel. On 21 March 1829, Wellington and Winchilsea met on Battersea fields. When the time came to fire, the Duke took aim and Winchilsea kept his arm down. The Duke fired wide to the right. Accounts differ as to whether he missed on purpose, an act known in dueling as a delope. Wellington claimed he did. However, he was noted for his poor aim and reports more sympathetic to Winchilsea claimed he had aimed to kill. Winchilsea did not fire, a plan he and his second had almost certainly decided upon before the duel.[164] Honour was saved and Winchilsea wrote Wellington an apology.[163]"

So dueling was still acceptable to high officials in the British government as late as 1828, though by the time Phineas Finn was published by Trollope covering the 1860s, Finn and Chiltern had to go secretly to Belgium since dueling was outlawed in England.

I wondered whether dueling was still practiced when Pickwick was published. What I have been able to find is that it was dying out in the 1830s, but was still practiced, so there is a real possibility of danger to Mr. Jingle, if he can't get out of the challenge.

According to the Wikipedia entry on the Duke of Wellington, who became prime minister in 1828, "The Earl of Winchilsea accused the Duke of "an insidious design for the infringement of our liberties and the introduction of Popery into every department of the State".[163] Wellington responded by immediately challenging Winchilsea to a duel. On 21 March 1829, Wellington and Winchilsea met on Battersea fields. When the time came to fire, the Duke took aim and Winchilsea kept his arm down. The Duke fired wide to the right. Accounts differ as to whether he missed on purpose, an act known in dueling as a delope. Wellington claimed he did. However, he was noted for his poor aim and reports more sympathetic to Winchilsea claimed he had aimed to kill. Winchilsea did not fire, a plan he and his second had almost certainly decided upon before the duel.[164] Honour was saved and Winchilsea wrote Wellington an apology.[163]"

So dueling was still acceptable to high officials in the British government as late as 1828, though by the time Phineas Finn was published by Trollope covering the 1860s, Finn and Chiltern had to go secretly to Belgium since dueling was outlawed in England.

Linda wrote: "

I guess my big question at this point is, I'm not quite sure what the "point" of the Pickwick Club is? Did I miss what the aim and goals of the club is? "

The PC seems just to be there, with no explanation as to what it's for or why named after Pickwick. At the time, clubs were in existence all over London, some famous and well established, others not. I think of the PC as akin to the private foundations that some people like to establish to give out relatively small donations to charities while getting credit under their name.

I guess my big question at this point is, I'm not quite sure what the "point" of the Pickwick Club is? Did I miss what the aim and goals of the club is? "

The PC seems just to be there, with no explanation as to what it's for or why named after Pickwick. At the time, clubs were in existence all over London, some famous and well established, others not. I think of the PC as akin to the private foundations that some people like to establish to give out relatively small donations to charities while getting credit under their name.

When I remind myself that we're right back at the beginning again, I can't help but give a little smile of pure pleasure - and also one of amazement! For who would have thought, honestly, that it would not just either fizzle out by the end, or metamorphose into something else. Also, it's lovely to have so much "new blood" with such insights in these last few novels.

When I remind myself that we're right back at the beginning again, I can't help but give a little smile of pure pleasure - and also one of amazement! For who would have thought, honestly, that it would not just either fizzle out by the end, or metamorphose into something else. Also, it's lovely to have so much "new blood" with such insights in these last few novels.The Pickwick Papers is a novel which, for me, has completely switched in my estimation. When younger, I found it boring, without a main story. Now, every page is a delight! And Dickens's lightheartedness and pure joie de vivre is infectious :) So enjoyable after the heaviness of the later reads.

Tristram - your comment about Mr. Tupman being a proto-Turveydrop made me anticipate another enjoyable prospect...

Since many of us have read many (or all) of his other novels together by now, how fascinating it will be to see other nascent characters. We've sometimes said who characters remind us of, in earlier novels. Now we'll be able to observe this in reverse. We can identify the early signs of someone - perhaps of a favourite character's dim beginnings - before they were fully realised.

Jean wrote: "

The Pickwick Papers is a novel which, for me, has completely switched in my estimation. When younger, I found it boring, without a main story. Now, every page is a delight! "

I hope to get there myself, with the aid of others here. I too, on earlier readings, found PP boring; indeed, I realize that I have never read it all the way through. So far, and it's only two chapters in, I'm not finding it all that enjoyable, basically because I think Dickens tries too hard to be funny. It's almost slapstick, which is a form of humor I do not like. I prefer the more subtle humor of Austen and others of her ilk, the more traditional "English humour" I was brought up with that sneaks up behind you and tickles your funny bone when you are least expecting it, rather than the in-your-face-you-need-to-laugh-now humor which I am finding so far in PP.

The Pickwick Papers is a novel which, for me, has completely switched in my estimation. When younger, I found it boring, without a main story. Now, every page is a delight! "

I hope to get there myself, with the aid of others here. I too, on earlier readings, found PP boring; indeed, I realize that I have never read it all the way through. So far, and it's only two chapters in, I'm not finding it all that enjoyable, basically because I think Dickens tries too hard to be funny. It's almost slapstick, which is a form of humor I do not like. I prefer the more subtle humor of Austen and others of her ilk, the more traditional "English humour" I was brought up with that sneaks up behind you and tickles your funny bone when you are least expecting it, rather than the in-your-face-you-need-to-laugh-now humor which I am finding so far in PP.

Although most of us have read through the first two chapters and know the stranger to be "Jingle" I thought it was worth pointing out that we don't actually get the name Jingle until later in the book if I remember correctly.

Although most of us have read through the first two chapters and know the stranger to be "Jingle" I thought it was worth pointing out that we don't actually get the name Jingle until later in the book if I remember correctly. As a first time reader of PP, and prior knowledge of how characters can come and go in a Dickens novel, I assumed the lack of a name was a sign the "stranger" wouldn't last long.

Anyone think there was a significant reason to the lack of name?

Matt wrote: "Although most of us have read through the first two chapters and know the stranger to be "Jingle" I thought it was worth pointing out that we don't actually get the name Jingle until later in the b..."

Matt wrote: "Although most of us have read through the first two chapters and know the stranger to be "Jingle" I thought it was worth pointing out that we don't actually get the name Jingle until later in the b..."I’m confused because I have read the first two chapters, and I didn’t know his name to be “Jingles,” as your post suggests to me... how is it that we know the stranger’s name if it isn’t revealed until later? Is there an implication, or an allusion, that I have overlooked in these two chapters?

I don’t know of any reasoning behind keeping this man nameless, as it pertains to this thread, other than it being a means to create intrigue...Because the stranger, is a “strange” fellow at present, and it’s fitting for him. Giving him a definitive name, at a later time, may reveal a more fleshed out character at that time; where the stranger reference is inapplicable, because he’s no longer a “stranger?” Pure conjecture on my part, I don’t know definitively, I have not read ahead

Everyman wrote: "Jean wrote: "

The Pickwick Papers is a novel which, for me, has completely switched in my estimation. When younger, I found it boring, without a main story. Now, every page is a delight! "

I hope ..."

Hi Everyman

Yes. The humour of PP does take a bit of getting used to, but I love it. Slapstick is one way to define much of the Pickwickian adventures. My way of approaching the scenes is to picture them as theatrical, melodramatic and even silly, with no apologies offered from Dickens. Dickens loved the theatre, and I think he is never far from this central point in PP. Physical comedy, situational comedy. verbal wit. Think of Jerry Lewis, Abbott and Costello, Red Skelton, Carol Burnett. I confess to still loving them all.

The Pickwick Papers is a novel which, for me, has completely switched in my estimation. When younger, I found it boring, without a main story. Now, every page is a delight! "

I hope ..."

Hi Everyman

Yes. The humour of PP does take a bit of getting used to, but I love it. Slapstick is one way to define much of the Pickwickian adventures. My way of approaching the scenes is to picture them as theatrical, melodramatic and even silly, with no apologies offered from Dickens. Dickens loved the theatre, and I think he is never far from this central point in PP. Physical comedy, situational comedy. verbal wit. Think of Jerry Lewis, Abbott and Costello, Red Skelton, Carol Burnett. I confess to still loving them all.

Ami wrote: "Matt wrote: "Although most of us have read through the first two chapters and know the stranger to be "Jingle" I thought it was worth pointing out that we don't actually get the name Jingle until l..."

Ami wrote: "Matt wrote: "Although most of us have read through the first two chapters and know the stranger to be "Jingle" I thought it was worth pointing out that we don't actually get the name Jingle until l..."Someone revealed his name to be Jingle in a previous post in this thread which is why I raised the point.

He is not named in the first two chapters.

Peter wrote: "Everyman wrote: "Jean wrote: "

Peter wrote: "Everyman wrote: "Jean wrote: "The Pickwick Papers is a novel which, for me, has completely switched in my estimation. When younger, I found it boring, without a main story. Now, every page is a de..."

I like it for these reasons and have found this to be the case as I get underway.

When I joined The Curiousities, the very first chapter I read with the group had bodies being pulled from The Thames.

Matt wrote: "Although most of us have read through the first two chapters and know the stranger to be "Jingle" I thought it was worth pointing out that we don't actually get the name Jingle until later in the book.....Anyone think there was a significant reason to the lack of name?"

Matt wrote: "Although most of us have read through the first two chapters and know the stranger to be "Jingle" I thought it was worth pointing out that we don't actually get the name Jingle until later in the book.....Anyone think there was a significant reason to the lack of name?"I have the Penguin Edition. Early on in chapter two, after the stranger saves Pickwick and friends from the scene in the street, there is an end note:

"You were present at that glorious scene, Sir?" said Mr Snodgrass.

"Present! think I was; (10) fired a musket, ...."

The end note reads:

10. Dickens added a corrective but otherwise clumsy footnote for the 1847 edition: "A remarkable instance of the prophetic force of Mr Jingle's imagination; this dialogue occurring in the year 1827, and the Revolution in 1830." The Revolution in question deposed the Bourbon dynasty from the French throne in favour of Louis-Philippe d'Orleans. In pointing out this anachronism, Dickens introduced another kind of mistake: the stranger has still to be named.

So, it sounds like it was simply a mistake on Dickens' part.

Everyman wrote: "The PC seems just to be there, with no explanation as to what it's for or why named after Pickwick. At the time, clubs were in existence all over London, some famous and well established, others not."

Everyman wrote: "The PC seems just to be there, with no explanation as to what it's for or why named after Pickwick. At the time, clubs were in existence all over London, some famous and well established, others not."Thanks! At first I thought the club had the aim of exploration and observation of perhaps nature? human nature? Not sure. And then they were to record and publish their findings. I'm not sure where that idea stuck in my head, though. Probably the Tittlebat reference.

Linda wrote: "Matt wrote: "Although most of us have read through the first two chapters and know the stranger to be "Jingle" I thought it was worth pointing out that we don't actually get the name Jingle until l..."

Linda wrote: "Matt wrote: "Although most of us have read through the first two chapters and know the stranger to be "Jingle" I thought it was worth pointing out that we don't actually get the name Jingle until l..."The Project Gutenberg edition which I am reading must be the 1847 text, then, since it has this footnote.

Patrick wrote: "Linda wrote: "Matt wrote: "Although most of us have read through the first two chapters and know the stranger to be "Jingle" I thought it was worth pointing out that we don't actually get the name ..."

Patrick wrote: "Linda wrote: "Matt wrote: "Although most of us have read through the first two chapters and know the stranger to be "Jingle" I thought it was worth pointing out that we don't actually get the name ..."Yes I actually pulled up the Project Gutenberg edition after reading your post and noticed the footnote in chapter 2.

Nice detective work Linda, it seems like it was definitely a mistake on Dickens part. Interesting nonetheless!

Peter wrote: " Dickens loved the theatre, and I think he is never far from this central point in PP. Physical comedy, situational comedy. verbal wit. Think of Jerry Lewis, Abbott and Costello, Red Skelton, Carol Burnett. I confess to still loving them all. "

I agree with you on his physical, situational comedy. Good way of putting it.

I actually don't like any of the comedians you like. I love Flanders and Swann, the early Bill Cosby (when he was making records of his comedy, such as the wonderful Noah), and Stanley Holloway, such as his Albert and the Lion.

Flanders and Swann:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VnbiV...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WHWnF...

Bill Cosby, Noah

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CgsFC...

Stanley Holloway, Albert and the Lion

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oaw-s...

I agree with you on his physical, situational comedy. Good way of putting it.

I actually don't like any of the comedians you like. I love Flanders and Swann, the early Bill Cosby (when he was making records of his comedy, such as the wonderful Noah), and Stanley Holloway, such as his Albert and the Lion.

Flanders and Swann:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VnbiV...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WHWnF...

Bill Cosby, Noah

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CgsFC...

Stanley Holloway, Albert and the Lion

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oaw-s...

Matt wrote: "Someone revealed his name to be Jingle in a previous post in this thread which is why I raised the point.

He is not named in the first two chapters. "

You're quite right on both counts.

It was our moderator, Tristram, who revealed the name in post #2 above. An inadvertent spoiler, fortunately not a major one, but nonetheless he gets one demerit. [g]

But it's the consequence of knowing the books well; it can be hard to do an extensive introduction/summary such as Tristram and Kim and Peter all so wonderfully, without slipping occasionally. But their contributions to the discussion are so rich and rewarding that I'm sure we all forgive the occasional slip.

He is not named in the first two chapters. "

You're quite right on both counts.

It was our moderator, Tristram, who revealed the name in post #2 above. An inadvertent spoiler, fortunately not a major one, but nonetheless he gets one demerit. [g]

But it's the consequence of knowing the books well; it can be hard to do an extensive introduction/summary such as Tristram and Kim and Peter all so wonderfully, without slipping occasionally. But their contributions to the discussion are so rich and rewarding that I'm sure we all forgive the occasional slip.

Everyman wrote: "Matt wrote: "Someone revealed his name to be Jingle in a previous post in this thread which is why I raised the point.

Everyman wrote: "Matt wrote: "Someone revealed his name to be Jingle in a previous post in this thread which is why I raised the point.He is not named in the first two chapters. "

You're quite right on both coun..."

I completely understand. Didn't intend to take anything away from Tristram's work and as you mentioned it certainly is not a major spoiler to know the name of the stranger.

Oh dear, I've read Pickwick Papers so often now - this is the fourth or fifth time, actually - that I look on the novel, its cast and plot probably the same way Vonnegut's Tralfamadorians look at time, and this is why the name of Alfred Jingle slipped into my recap.

I beg the Secretary to note and to take down, however, that mention of Alfred Jingle's name was made entirely in a Pickwickian sense, and is therefore to be understood in a strictly Pickwickian sense, and not as a mean attempt at a spoiler.

I beg the Secretary to note and to take down, however, that mention of Alfred Jingle's name was made entirely in a Pickwickian sense, and is therefore to be understood in a strictly Pickwickian sense, and not as a mean attempt at a spoiler.

As many of you have already written, the first two chapters of PP are like a breath of fresh air, and once again I feel elevated by the vibrant mood of good-humour and fun the novel creates. It's simply like spring coming in winter, like revisiting a ever-green pasture (which does not necessarily make one a quadruped)! I really enjoyed my first chapters of Pickwick after so many years.

As to the humour, yes, it may be a bit on the slapstick side, but, to me, there is nothing wrong with slapstick. Just watch the beginning of Chaplin's "City Lights", and you'll see how difficult it is, and how effective when done right. Or take Laurel and Hardy ...

But I also feel reminded of "Seinfeld" a bit, because like Jerry and his friends, the Pickwickians tend to find themselves faced with absurd challenges and adversities, being victims of strange and untoward misunderstandings. The only difference between Pickwick and Jerry (or George) is that Pickwick is a truly likeable and unselfish person.

As to the humour, yes, it may be a bit on the slapstick side, but, to me, there is nothing wrong with slapstick. Just watch the beginning of Chaplin's "City Lights", and you'll see how difficult it is, and how effective when done right. Or take Laurel and Hardy ...

But I also feel reminded of "Seinfeld" a bit, because like Jerry and his friends, the Pickwickians tend to find themselves faced with absurd challenges and adversities, being victims of strange and untoward misunderstandings. The only difference between Pickwick and Jerry (or George) is that Pickwick is a truly likeable and unselfish person.

Thanks Everyman, and you're right, it is so hard not to give anything away. It's good I have read all of Dickens before because anyone and everyone who has written a commentary on any and every illustration feels it necessary to compare an early illustration with a later one, and they end up with spoiler after spoiler. That's why I never tell where I'm getting my information, I don't want to give anything away, I just rewrite the things.

And it's all good Matt. :-)

And it's all good Matt. :-)

Hi everybody,

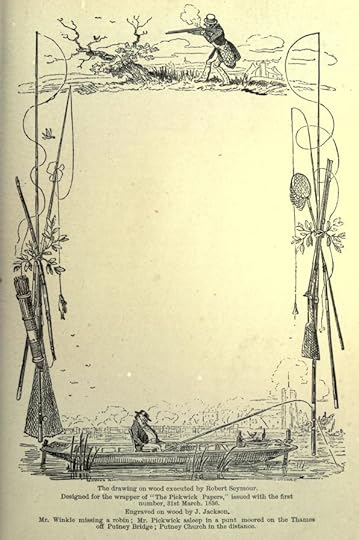

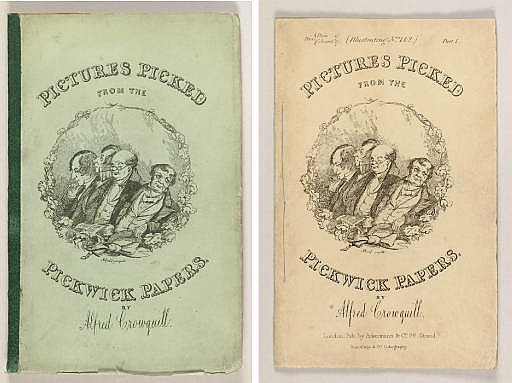

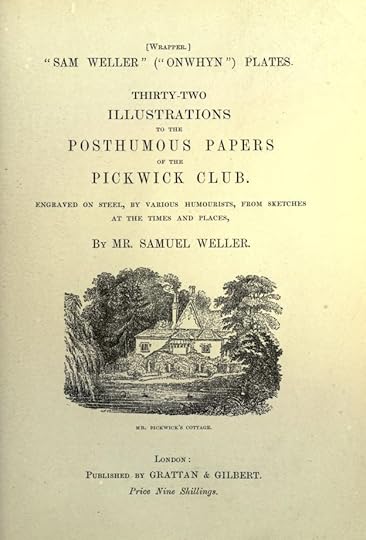

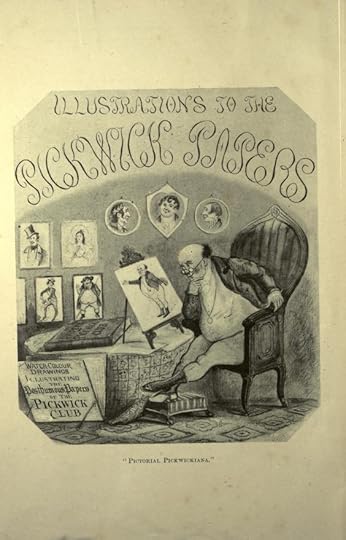

Before I get to the illustrations I'd like to tell you a little about them and that is, there are a lot of them. I will tell you more about this later, but first I want to start with the artists who illustrated the first edition of Pickwick. Those artists were Robert Seymour, Robert Buss, and Phiz. Buss we won't get to until the third installment, so more about him then, the main artist for the first two installments was Robert Seymour, but I'm also including Phiz's illustrations for the same threads, title-pages, frontispieces, things like that. Since Seymour seems so important to this book I've added a biography of him, and here we go.............

Robert Seymour was a blithe, pleasant, busy little man, had industriously administered to the amusement of his generation throughout a hard-working career, already extending to a score of busy years, by producing hundreds of humorous pictures, and was popularly appreciated as the droll designer of "Seymour's Sketches," amongst innumerable similar comic productions, which had made his name reasonable familiar in the annuals of art and letters, as recognised in his generation.

Until 1827, Seymour confined his labours to drawing for the wood-engravers. He now essayed the art of etching upon plates of steel or copper, simulating the style and manner of George Cruikshank; he even ventured to affix the nom de plume of "Shortshanks" to his early caricatures, until he received a remonstrance from the famous George himself. Having attained some proficiency in both etching and lithography, he determined to make practical use of his experience, and in 1833 designed a series of twelve lithographic plates for a new edition of a work entitled "Maxims and Hints for an Angler," in which the humours of the piscatorial art were excellently rendered; he also executed a number of similar designs portraying, with laughable effect, the adventures and misadventures of the very "counter-jumpers" whose ways and habits came under his keen, observant eye. These amusing pictures, drawn on stone with pen-and-ink, and published as a collection of "Sketches by Seymour," achieved an immense popularity, and were chiefly the means of rendering his name generally familiar.

In 1835, this indefatigable hard worker was, as usual, very busy indeed; born with the century, the designer was at that time some thirty-five years of age. There were periodicals, like the "Figaro in London,," and a rival venture, "The Comic Magazine," to which he was week by week contributing comic illustrations, finding time meanwhile for numerous etchings on steel of a more advanced and exacting order. At the same time, for the elder ThomasMcLean of the Haymarket, Seymour was producing a great deal of meritorious humoristic work, - separate caricatures, - after the nature of those made famous by the brothers G. and R. Cruikshank, Heath, and many other caricaturists under similar auspices, and enlisted under the same patronage, issued in the familiar form of pictorial skits in folio, etched on copper, drawn on stone, and colored by hand. ..........

With all this work daily growing under his hands, Seymour in 1835 proposed to turn his recreations, which were of a sporting nature into further comic pictorial capital; and, pursuing the vein which had secured his name most popular recognition with the "Cockney Sporting Sketches," he finally projected the scheme of a "Nimrod Club," the members to be led into ludicrous adventures owing to their general want of skill and grotesque incompetence; the series to be published in monthly parts, price one shilling.

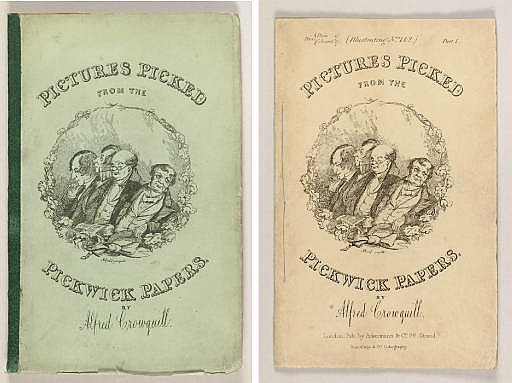

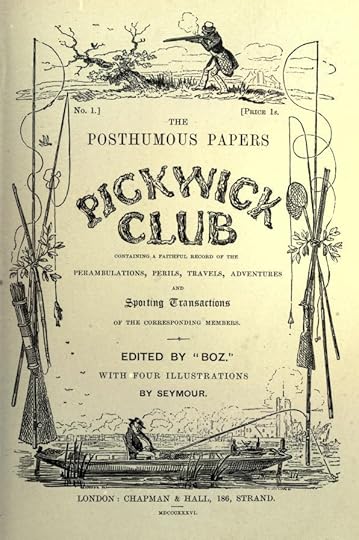

The undertaking was so far put in motion that Seymour etched four plates from the drawings which he had made, however the "Sporting Club" project lay in abeyance, and the four plates that were etched remained in the artist's drawer for about three months. Unfortunately, Seymour does not enlighten us upon the subject of the wrapper design, much depended on the attractive character of the designs on the covers of these monthly parts, and the "crux" of Seymour's original plans is found in this design, now so familiar on the green covers of the monthly numbers of "Pickwick"; otherwise, by a coincidence, although in every way consistent with the "Nimrod Club" notion, having no connection whatever with the course pursued and brought to so amazingly successful an issue by Dickens, who never in any way carried out the suggestions thus indicated on the actual wrapper of "Pickwick." The theory of adventures planned to be delineated, but never executed by the artist, probably owing to his sudden exit, are evidently foreshadowed; there are several fishing-rods, for "fly" and "bottom" fishing; nets, both "landing" and "casting"; a bow and quiver of arrows, on the archery side; all implements suggesting "gentle Waltonian" recreations, in which the designer was an adept, and the future illustrious author was not. There is the typical Cockney sportsman of comic fiction, ultra-professional in equipment, elaborately missing a dicky-bird, perched at two guns' length from the shooter; the bird, calmly contemptuous of the sportsman, evincing no uneasiness or alarm; the would-be sportsman, described subsequently by "Boz" as "Mr. Winkle", was a favorite figure with the artist, and often occurs in Seymour's sketches. There too is a farcical version of a well-known character, fast asleep, with his fishing-rod between his knees, and blackbirds eating his pie.

Dickens in the preface to the first cheap edition of "Pickwick" (1847), writes:—

"I was a young man of three-and-twenty when the present publishers [Chapman & Hall], attracted by some pieces I was at that time writing in the Morning Chronicle newspaper (of which one series had lately been collected and published in two volumes, illustrated by my esteemed friend George Cruikshank), waited upon me to propose a something that should be published in shilling numbers.... The idea propounded to me was that the monthly something should be a vehicle for certain plates to be executed by Mr. Seymour, and there was a notion, either on the part of that admirable humorous artist or of my visitor (I forget which), that a 'Nimrod Club,' the members of which were to go out shooting, fishing, and so forth, and getting themselves into difficulties through their want of dexterity, would be the best means of introducing these. I objected, on consideration, that although born and partly bred in the country, I was no great sportsman, except in regard of all kinds of locomotion; that the idea was not novel, and had been already much used; that it would be infinitely better for the plates to arise naturally out of the text; and that I should like to take my own way, with freer range of English scenes and people, and was afraid I should ultimately do so in any case, whatever course I might prescribe to myself at starting. My views being deferred to, I thought of Mr. Pickwick, and wrote the first number, from the proof-sheets of which Mr. Seymour made his drawing of the Club, and that happy portrait of its founder, by which he is always recognised, and which may be said to have made him a reality. I connected Mr. Pickwick with a club because of the original suggestion, and I put in Mr. Winkle expressly for the use of Mr. Seymour."

Before I get to the illustrations I'd like to tell you a little about them and that is, there are a lot of them. I will tell you more about this later, but first I want to start with the artists who illustrated the first edition of Pickwick. Those artists were Robert Seymour, Robert Buss, and Phiz. Buss we won't get to until the third installment, so more about him then, the main artist for the first two installments was Robert Seymour, but I'm also including Phiz's illustrations for the same threads, title-pages, frontispieces, things like that. Since Seymour seems so important to this book I've added a biography of him, and here we go.............

Robert Seymour was a blithe, pleasant, busy little man, had industriously administered to the amusement of his generation throughout a hard-working career, already extending to a score of busy years, by producing hundreds of humorous pictures, and was popularly appreciated as the droll designer of "Seymour's Sketches," amongst innumerable similar comic productions, which had made his name reasonable familiar in the annuals of art and letters, as recognised in his generation.

Until 1827, Seymour confined his labours to drawing for the wood-engravers. He now essayed the art of etching upon plates of steel or copper, simulating the style and manner of George Cruikshank; he even ventured to affix the nom de plume of "Shortshanks" to his early caricatures, until he received a remonstrance from the famous George himself. Having attained some proficiency in both etching and lithography, he determined to make practical use of his experience, and in 1833 designed a series of twelve lithographic plates for a new edition of a work entitled "Maxims and Hints for an Angler," in which the humours of the piscatorial art were excellently rendered; he also executed a number of similar designs portraying, with laughable effect, the adventures and misadventures of the very "counter-jumpers" whose ways and habits came under his keen, observant eye. These amusing pictures, drawn on stone with pen-and-ink, and published as a collection of "Sketches by Seymour," achieved an immense popularity, and were chiefly the means of rendering his name generally familiar.

In 1835, this indefatigable hard worker was, as usual, very busy indeed; born with the century, the designer was at that time some thirty-five years of age. There were periodicals, like the "Figaro in London,," and a rival venture, "The Comic Magazine," to which he was week by week contributing comic illustrations, finding time meanwhile for numerous etchings on steel of a more advanced and exacting order. At the same time, for the elder ThomasMcLean of the Haymarket, Seymour was producing a great deal of meritorious humoristic work, - separate caricatures, - after the nature of those made famous by the brothers G. and R. Cruikshank, Heath, and many other caricaturists under similar auspices, and enlisted under the same patronage, issued in the familiar form of pictorial skits in folio, etched on copper, drawn on stone, and colored by hand. ..........

With all this work daily growing under his hands, Seymour in 1835 proposed to turn his recreations, which were of a sporting nature into further comic pictorial capital; and, pursuing the vein which had secured his name most popular recognition with the "Cockney Sporting Sketches," he finally projected the scheme of a "Nimrod Club," the members to be led into ludicrous adventures owing to their general want of skill and grotesque incompetence; the series to be published in monthly parts, price one shilling.

The undertaking was so far put in motion that Seymour etched four plates from the drawings which he had made, however the "Sporting Club" project lay in abeyance, and the four plates that were etched remained in the artist's drawer for about three months. Unfortunately, Seymour does not enlighten us upon the subject of the wrapper design, much depended on the attractive character of the designs on the covers of these monthly parts, and the "crux" of Seymour's original plans is found in this design, now so familiar on the green covers of the monthly numbers of "Pickwick"; otherwise, by a coincidence, although in every way consistent with the "Nimrod Club" notion, having no connection whatever with the course pursued and brought to so amazingly successful an issue by Dickens, who never in any way carried out the suggestions thus indicated on the actual wrapper of "Pickwick." The theory of adventures planned to be delineated, but never executed by the artist, probably owing to his sudden exit, are evidently foreshadowed; there are several fishing-rods, for "fly" and "bottom" fishing; nets, both "landing" and "casting"; a bow and quiver of arrows, on the archery side; all implements suggesting "gentle Waltonian" recreations, in which the designer was an adept, and the future illustrious author was not. There is the typical Cockney sportsman of comic fiction, ultra-professional in equipment, elaborately missing a dicky-bird, perched at two guns' length from the shooter; the bird, calmly contemptuous of the sportsman, evincing no uneasiness or alarm; the would-be sportsman, described subsequently by "Boz" as "Mr. Winkle", was a favorite figure with the artist, and often occurs in Seymour's sketches. There too is a farcical version of a well-known character, fast asleep, with his fishing-rod between his knees, and blackbirds eating his pie.

Dickens in the preface to the first cheap edition of "Pickwick" (1847), writes:—

"I was a young man of three-and-twenty when the present publishers [Chapman & Hall], attracted by some pieces I was at that time writing in the Morning Chronicle newspaper (of which one series had lately been collected and published in two volumes, illustrated by my esteemed friend George Cruikshank), waited upon me to propose a something that should be published in shilling numbers.... The idea propounded to me was that the monthly something should be a vehicle for certain plates to be executed by Mr. Seymour, and there was a notion, either on the part of that admirable humorous artist or of my visitor (I forget which), that a 'Nimrod Club,' the members of which were to go out shooting, fishing, and so forth, and getting themselves into difficulties through their want of dexterity, would be the best means of introducing these. I objected, on consideration, that although born and partly bred in the country, I was no great sportsman, except in regard of all kinds of locomotion; that the idea was not novel, and had been already much used; that it would be infinitely better for the plates to arise naturally out of the text; and that I should like to take my own way, with freer range of English scenes and people, and was afraid I should ultimately do so in any case, whatever course I might prescribe to myself at starting. My views being deferred to, I thought of Mr. Pickwick, and wrote the first number, from the proof-sheets of which Mr. Seymour made his drawing of the Club, and that happy portrait of its founder, by which he is always recognised, and which may be said to have made him a reality. I connected Mr. Pickwick with a club because of the original suggestion, and I put in Mr. Winkle expressly for the use of Mr. Seymour."

Great bit of detective work Linda!

Great bit of detective work Linda!I seem to remember that Dickens got quite a lot of criticism for making mistakes in his first historical novel, Barnaby Rudge, so was extremely careful to check everything for his only other historical novel. When he was about to write A Tale of Two Cities, wherever he went he carried his friend, Thomas Carlyle’s “History of the French Revolution” with him, reading it over and over again. Dickens jokingly claimed to have read the book 500 times, and used Carlyle’s book as a reference source.

But in these early days, he was probably far more cavalier about the facts!

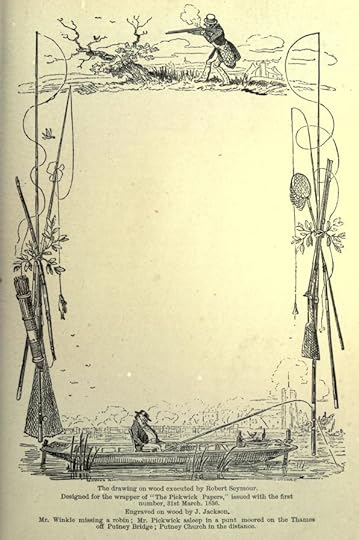

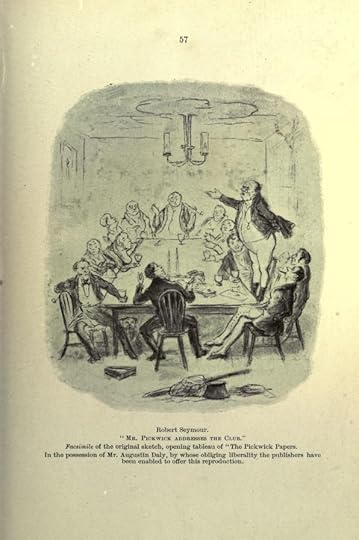

Mr. Pickwick Addresses the Club

Frontispiece

Chapter 1

Robert Seymour

Text Illustrated:

What a study for an artist did that exciting scene present! The eloquent Pickwick, with one hand gracefully concealed behind his coat tails, and the other waving in air to assist his glowing declamation; his elevated position revealing those tights and gaiters, which, had they clothed an ordinary man, might have passed without observation, but which, when Pickwick clothed them — if we may use the expression — inspired involuntary awe and respect; surrounded by the men who had volunteered to share the perils of his travels, and who were destined to participate in the glories of his discoveries. On his right sat Mr. Tracy Tupman — the too susceptible Tupman, who to the wisdom and experience of maturer years superadded the enthusiasm and ardour of a boy in the most interesting and pardonable of human weaknesses — love. Time and feeding had expanded that once romantic form; the black silk waistcoat had become more and more developed; inch by inch had the gold watch-chain beneath it disappeared from within the range of Tupman's vision; and gradually had the capacious chin encroached upon the borders of the white cravat: but the soul of Tupman had known no change — admiration of the fair sex was still its ruling passion. On the left of his great leader sat the poetic Snodgrass, and near him again the sporting Winkle; the former poetically enveloped in a mysterious blue cloak with a canine-skin collar, and the latter communicating additional lustre to a new green shooting-coat, plaid neckerchief, and closely-fitted drabs.

Commentary:

The first plate, marking the inauguration of the Cockney sporting club, is set on May 12, 1827. The principals, apart from Pickwick (holding forth while standing on a chair) are Tracy Tupman, the poet Augustus Snodgrass, and the experienced "sportsman," Nathaniel Winkle. As Pickwick addresses the club, Mr. Blotton (one of three figures in the first illustration: the man with the pipe, up centre; the man gesticulating, down centre; or the sour-looking gentleman with the pipe, down left) denounces Pickwick as a "Humbug," an insult which Ebenezer Scrooge made famous seven years later in A Christmas Carol, implying a species of imposture, deceit, or delusion. That Robert Seymour was not much invested in the club members so much as their "sporting" activities is implied by the artist's failure to individualise the other club members, and by their postures suggest which figure is Blotton. The passage realised suggests that Tupman is to Pickwick's immediate right, and that Snodgrass and Winkle are to Pickwick's immediate left.

Nothing in the initial illustration prompts a reader's sympathy with any of the characters, and the illustrator fails to suggest a precise narrative moment for realisation, other than the visual allusion to Pickwick's having one hand in his coat tails. But Seymour was a well-known, popular artist, so Dickens's bided his time.

Facsimile of the original sketch, opening tableau of The Pickwick Papers.

Reading the above commentaries, it is most interesting to see how this club's membership so closely resembles the fictional one we are studying in The PP.

Reading the above commentaries, it is most interesting to see how this club's membership so closely resembles the fictional one we are studying in The PP.With all due respect to the learned members, I feel it is a good thing that we are reviewing a comedy to start with. Considering the rest of Dickens's work, a little laughter makes this work so enchanting.

And as someone noted earlier above, this would make a delightful screwball comedy in the fashion of those from the 30's and 40's.

Mr. Pickwick Addresses The Pickwick Club

Chapter 1

Hablot Knight Browne - Phiz

Facsimile of the water-color drawing by Phiz of his version, see the Seymour etching. The above version was produced, in later years, by Phiz to supply the place of the original design by Seymour (which the publishers had not retained) in a complete series of "Pickwick" drawings, executed as a commission for a friendly patron, the late Mr. F. W. Cosens, of Melberry Road.

The Pugnacious Cabman

Robert Seymour

Commentary:

Dickens, having objected to William Hall's suggestions about penning the adventures of a "Nimrod Club," now began to direct the narrative in a direction different from Robert Seymour's original conception In "The Pugnacious Cabman," we revert to the streets of London, the comic milieu of Sketches by Boz. The date is 13 May 1827, and the setting is the Golden Cross, where Tupman, Snodgrass, and Winkle — the core Pickwickians — have been awaiting their chief.

Asa Collins and Guiliano note, the vehicle that Pickwick has hired (background, center) is not the old-fashioned, heavy hackney coach of eighteenth-century London, but the new, light, one-horse equipage originally called a "cabriolet," the term used in Paris. The English, however, quickly reduced the elegant French expression to "cab," and so Pickwick's belligerent driver (in the white duster, right of centre) is a "cabman," who sits when driving on a perch on the right-hand side, so that passenger and driver might easily converse, as Pickwick and his driver do on the way to the Golden Cross coaching inn. This destination reinforces the fact that the date of the action is in the decade previous to the serial's publication, for the inn disappeared in 1829 to make way for the nation's tribute to the heroic Lord Nelson, Trafalgar Square, "the old Golden Cross Hotel standing on what was to be the site of Nelson's Column" (Collins and Guiliano 24, note 4).

Text Illustrated:

"Would anybody believe," continued the cab–driver, appealing to the crowd, "would anybody believe as an informer'ud go about in a man's cab, not only takin' down his number, but ev'ry word he says into the bargain' (a light flashed upon Mr. Pickwick — it was the note–book).

"Did he though?" inquired another cabman.

"Yes, did he," replied the first; "and then arter aggerawatin' me to assault him, gets three witnesses here to prove it. But I'll give it him, if I've six months for it. Come on!" and the cabman dashed his hat upon the ground, with a reckless disregard of his own private property, and knocked Mr. Pickwick's spectacles off, and followed up the attack with a blow on Mr. Pickwick's nose, and another on Mr. Pickwick's chest, and a third in Mr. Snodgrass's eye, and a fourth, by way of variety, in Mr. Tupman's waistcoat, and then danced into the road, and then back again to the pavement, and finally dashed the whole temporary supply of breath out of Mr. Winkle's body; and all in half-a-dozen seconds.

"Where's an officer?’ said Mr. Snodgrass.

"Put 'em under the pump," suggested a hot–pieman.

"You shall smart for this," gasped Mr. Pickwick.

"Informers!" shouted the crowd.

"Come on," cried the cabman, who had been sparring without cessation the whole time. [chapter 2.]

Nothing in the initial illustration prompts a reader's sympathy with any of the characters, and the illustrator fails to suggest a precise narrative moment for realization, other than the visual allusion to Pickwick's having one hand in his coat tails.

What is odd about Seymour's construction of the scene in the street as a mob gathers to watch the altercation between Pickwick and his henchmen on the one hand and the indignant cab-driver on the other is that the viewer cannot readily determine which of the many figures is that of the stranger, whom the text describes as wearing a distinctive green overcoat. Since this scene introduces the reader to this significant and recurring character, one would expect that Seymour would have granted him much greater prominence. He is one of those Dickens characters readily identifiable by his distinctive voice, principally by his cynical tone and staccato syntax, and his having a long, lean appearance and perpetually smirking expression (to say nothing of a prominent nose) should render him instantly recognizable, but nobody in the congested scene resembles the character. This would seem to be an oversight on Seymour's part, but Dickens may not have briefed him on the importance of clearly depicting him, who is probably the man in the white beaver immediately behind Pickwick, to the left. The angry cab-driver, then, would by elimination be the figure in the "duster" in the space between the carefully described hot-pie man (right) and Pickwick (centre), his fists raised in defiance. Otherwise, Seymour has conveyed the essential chaos and the elegant urban backdrop effectively, even to the point of having one curious bystander climb a lamp standard to get a better view. Here we do not have the benign, charming Pickwick of the later illustrations, by an angry, vociferous Pickwick who stands up for himself, even when confronted by a mob mistrustful of his motives and suspecting him of being a police informant.

Facsimile of the original sketch.

The Sagacious Dog

Chapter 2

Robert Seymour

Text Illustrated:

‘Fine pursuit, sir—fine pursuit.—Dogs, Sir?’

‘Not just now,’ said Mr. Winkle.

‘Ah! you should keep dogs—fine animals—sagacious creatures—dog of my own once—pointer—surprising instinct—out shooting one day—entering inclosure—whistled—dog stopped—whistled again—Ponto—no go; stock still—called him—Ponto, Ponto—wouldn’t move—dog transfixed—staring at a board—looked up, saw an inscription—“Gamekeeper has orders to shoot all dogs found in this inclosure”—wouldn’t pass it—wonderful dog—valuable dog that—very.’

‘Singular circumstance that,’ said Mr. Pickwick. ‘Will you allow me to make a note of it?’

Commentary:

In 1887 Messrs. Chapman & Hall appropriately celebrated the Jubilee of "The Pickwick Papers" by publishing an Edition de luxe, with facsimiles of the original drawings made for the work, or, rather, of as many of these as were then available. In the editor's preface it is stated that four out of the seven drawings etched by Seymour for "Pickwick" had disappeared, but it afterwards transpired that two of the missing designs remained in the possession of the artist's family, until they were sold to a private purchaser, who, in 1889, disposed of them by auction. Of these drawings, therefore, only one, viz., "The Sagacious Dog," is undiscoverable.

Dr. Slammer's Defiance [of Jingle]

Chapter 2

Robert Seymour

Text Illustrated:

Silently and patiently did the doctor bear all this, and all the handings of negus, and watching for glasses, and darting for biscuits, and coquetting, that ensued; but, a few seconds after the stranger had disappeared to lead Mrs. Budger to her carriage, he darted swiftly from the room with every particle of his hitherto-bottled-up indignation effervescing, from all parts of his countenance, in a perspiration of passion.

The stranger was returning, and Mr. Tupman was beside him. He spoke in a low tone, and laughed. The little doctor thirsted for his life. He was exulting. He had triumphed.

‘Sir!’ said the doctor, in an awful voice, producing a card, and retiring into an angle of the passage, ‘my name is Slammer, Doctor Slammer, sir—97th Regiment—Chatham Barracks—my card, Sir, my card.’ He would have added more, but his indignation choked him.

‘Ah!’ replied the stranger coolly, ‘Slammer—much obliged—polite attention—not ill now, Slammer—but when I am—knock you up.’

‘You—you’re a shuffler, sir,’ gasped the furious doctor, ‘a poltroon—a coward—a liar—a—a—will nothing induce you to give me your card, sir!’