The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

The Pickwick Papers

The Pickwick Papers

>

PP, Chp. 01-02

Kim wrote: "He was about the middle height, but the thinness of his body, and the length of his legs, gave him the appearance of being much taller."

And yet almost every illustrator makes him a portly gentleman of no particular tallness.

And yet almost every illustrator makes him a portly gentleman of no particular tallness.

Matt wrote: "Ami wrote: "Matt wrote: "Although most of us have read through the first two chapters and know the stranger to be "Jingle" I thought it was worth pointing out that we don't actually get the name Ji..."

Matt wrote: "Ami wrote: "Matt wrote: "Although most of us have read through the first two chapters and know the stranger to be "Jingle" I thought it was worth pointing out that we don't actually get the name Ji..."Thank you! (I do not know why my edition

revealed the stranger's name in the footnotes.) Why is Jingle's name withheld?

revealed the stranger's name in the footnotes.) Why is Jingle's name withheld?

What do you think of how Dickens manages to give a short characterization of each of the Pickwickians in this second chapter?

What do you think of how Dickens manages to give a short characterization of each of the Pickwickians in this second chapter?What can I add that has not been said? I fear I may find myself saying this over and over again, but : Dickens may have missed his opportunity to act professionally on the Victorian stage. Yet, he writes like an actor: embraces the limitations of having to spin a tale prompted by Seymour's drawings, the Pickwickians' clothing are merely expressions of their characters. (Nothing is taken for granted.Each garment is worn for a reason. )

I found this article entitled "At Home On the Stage: Dickens and the Theatre" which reveals that: "Dickens had a theatrical personality. He was inclined to wear bright colors and flashy items (like a gold pocket watch with a large fancy chain), and he tended to stand out in crowds of people wearing more muted colors. " Read more here: https://athomeonthestage.wordpress.com/

Since we are focusing on the attire of his characters why not the author, right?

After our first round through Dickens, especially with his later novels so fresh in mind, how do the first chapters of The Pickwick Papers appeal to you?

This is my first time through. So with fresh eyes, I'll say the opening was difficult to push past. It's disorienting to first be introduced to the editor (or editors) of the Pickwick Papers who never introduce themselves. Then to plunge coldly into a document which reads like legalese reading about an important club you've never heard of. Why are these men so self-important? What have they done at this point to deserve my adoration?

This is perhaps the joke.

I'm glad to push through the first couple pages, because I have attempted to read this book before, but was intimidated by the disarming first chapter.

The Dickens we are familiar with and love is within these pages: "The punctual servant of all work, the sun, had just risen and begun to strike light on the morning..." is perhaps the greatest opening sentence of any chapter of any book written in the English language. So yes, it was worth pushing through the pesky 1st.

Tristam wrote: I always understood "meaning something in the Pickwickian sense" as "meaning something in a way that is not meant to give offense", i.e. not in the sense the word in question is usually understood.

Tristam wrote: I always understood "meaning something in the Pickwickian sense" as "meaning something in a way that is not meant to give offense", i.e. not in the sense the word in question is usually understood.I think Mr. Blotton was called on to take back his fervent expressions but he could not do so without, so he thought, losing face...

My two cents:

I'm reading the black Penguin Classics edition, and my copy has an endnote for that remark at the end of Ch.1 about Mr. Blotton using the word in its "Pickwickian sense."

It states:

A notorious parliamentary slanging match between Brougham and Canning in April 1823 was resolved by Brougham's plea that his accusations had been directed at Canning's official, (not his private), character. Parliamentarians of the 1830s took Dickens' jibe to heart. In 1838, one MP remarked that this 'single stroke' of Dickens's pen had killed off the old excuse that calumnies 'were only meant to apply "in a parliamentary sense."'

Even without that insight, I think it's clear that Blotton was using a flimsy excuse to save face. And it's a great line to show the pompousness of the character, and perhaps the club itself.

Meanwhile, I'm already in love with Pickwick and his friends. Pickwick does not strike me as pompous, but maybe hapless. We already see his observational skills are not as sharp as he believes them to be. (I wanted to hug him when it slowly dawns on him that his jotting notes into his notebook is what has angered the cabman.) I smiled and giggled all through Ch.2. I've never read PP before, so I hope this keeps up. :-)

Kim wrote: "Furnival's Inn, Wednesday Evening, 1835.

Kim wrote: "Furnival's Inn, Wednesday Evening, 1835."My dearest Kate,

The House is up; but I am very sorry to say that I must stay at home. I have had a visit from the publishers this morning, and the story..."

Kim, thanks for posting that letter. Love this glimpse of a young Nobody Dickens modestly boasting to his Kate that he now has a new job for a pub to be written "entirely by myself"!

Kim wrote: "Furnival's Inn, Wednesday Evening, 1835.

"My dearest Kate,

The House is up; but I am very sorry to say that I must stay at home. I have had a visit from the publishers this morning, and the story..."

Kim

What incredible letters. We get to read the creative birth of characters, their actions and what the author plans to do with then next. It is as if we are watching a live-streaming documentary. Fascinating.

Jess

I, too, share your ideas and insights on Dickens and the theatre. The characters of Dickens are all so vivid and unique. Their dress, their speech all so fresh. Dickens’s lifelong affection and participation in theatrical endeavours live in his novels. I recently came across a phrase of Santayana’s that “ when people say that Dickens exaggerates, it seems to me that they can have no eyes and no ears.” I like that phrase very much. Perhaps Dickens also had a greater sensitivity to those around him on the streets than the rest of us.

The link you provided was very interesting. Thank you.

Cheryl

Something tells me that Dickens will keep the energy level high in PP. I”m glad you are enjoying the fist chapters. More fun is yet to come.

"My dearest Kate,

The House is up; but I am very sorry to say that I must stay at home. I have had a visit from the publishers this morning, and the story..."

Kim

What incredible letters. We get to read the creative birth of characters, their actions and what the author plans to do with then next. It is as if we are watching a live-streaming documentary. Fascinating.

Jess

I, too, share your ideas and insights on Dickens and the theatre. The characters of Dickens are all so vivid and unique. Their dress, their speech all so fresh. Dickens’s lifelong affection and participation in theatrical endeavours live in his novels. I recently came across a phrase of Santayana’s that “ when people say that Dickens exaggerates, it seems to me that they can have no eyes and no ears.” I like that phrase very much. Perhaps Dickens also had a greater sensitivity to those around him on the streets than the rest of us.

The link you provided was very interesting. Thank you.

Cheryl

Something tells me that Dickens will keep the energy level high in PP. I”m glad you are enjoying the fist chapters. More fun is yet to come.

Julie wrote: "Kim wrote: "Furnival's Inn, Wednesday Evening, 1835.

Julie wrote: "Kim wrote: "Furnival's Inn, Wednesday Evening, 1835."My dearest Kate,

The House is up; but I am very sorry to say that I must stay at home. I have had a visit from the publishers this morning, a..."

O, wow, I almost missed this, but yes, thank you!

"in company with a very different character from any I have yet described, who I flatter myself will make a decided hit!"---love this so much! Jingle surprising even Dickens!

Mary Lou, Ami, and Julie ... and all Curiosities

What a delight to see such commentary and discussion on PP. I think Mary Lou is correct in stating that Pickwick’s appearance is perfect as is. Somehow, a thin Pickwick would just not do. With his glasses, stance, and ability to climb up on a chair to deliver his remarks to the club, he is perfectly cast. I think Dickens has wisely cast the other characters as well. With the mysterious thin man who joins the Pickwickians in the coach, the size/shape difference can also be played up for all it’s worth. Could we ever have accepted twin large or thin men as Laurel and Hardy?

Ami and Julie have noted how effective the opening sentences are in chapters 1 and 2. Yes. A new chapter perhaps will often continue to be signaled with a morning or the sun rising. Tristram commented on how we have a mock-epic thread that runs through our first two chapters and how there is a hint of an odyssey as well. Spot on, I think. It is too early to determine how close - and even if - Dickens was faintly shading the PP as heroic, but our Pickwick Club members do seem to get themselves into interesting situations with equally interesting people so far. Perhaps if Dickens begins a chapter by referring to the rosy fingers of dawn we will know better if he is channeling his inner Homer. ; - )).

What a delight to see such commentary and discussion on PP. I think Mary Lou is correct in stating that Pickwick’s appearance is perfect as is. Somehow, a thin Pickwick would just not do. With his glasses, stance, and ability to climb up on a chair to deliver his remarks to the club, he is perfectly cast. I think Dickens has wisely cast the other characters as well. With the mysterious thin man who joins the Pickwickians in the coach, the size/shape difference can also be played up for all it’s worth. Could we ever have accepted twin large or thin men as Laurel and Hardy?

Ami and Julie have noted how effective the opening sentences are in chapters 1 and 2. Yes. A new chapter perhaps will often continue to be signaled with a morning or the sun rising. Tristram commented on how we have a mock-epic thread that runs through our first two chapters and how there is a hint of an odyssey as well. Spot on, I think. It is too early to determine how close - and even if - Dickens was faintly shading the PP as heroic, but our Pickwick Club members do seem to get themselves into interesting situations with equally interesting people so far. Perhaps if Dickens begins a chapter by referring to the rosy fingers of dawn we will know better if he is channeling his inner Homer. ; - )).

As I said before, there were a lot of artists that illustrated Pickwick. Not only those that did their own illustrations, but those who illustrated later editions. Don't worry, it may not seem like it this week, but I promise the weeks coming won't be so filled up. Not with all the introductions of the artists anyway. And, while I wanted to give you a glimpse of all of them, I may not use them all every week. We shall see. Now I'll move on to those artists I consider "Dickens" artists because they are the ones that usually show up in illustration searches having illustrated the later editions. I'll start with Sol Eytinge Jr.

The Pickwick Club

Chapter 1

Sol Eytinge Jr.

Diamond Edition 1867

Commentary:

In this initial full-page multiple-character study in the compact American "Diamond Edition," the principal members of Mr. Pickwick's club appear, as in the text:

'That the Corresponding Society of the Pickwick Club is therefore hereby constituted; and that Samuel Pickwick, Esq., G.C.M.P.C., Tracy Tupman, Esq., M.P.C., Augustus Snodgrass, Esq., M.P.C., and Nathaniel Winkle, Esq., M.P.C., are hereby nominated and appointed members of the same. . . . [ch. 1, p. 17 in The Diamond Edition]

In the longer programs of illustration — those by Seymour and Browne (1836-37), Browne in the British Household Edition (1873), and Nast in American Household Edition — these characters occur repeatedly. However, despite their importance as continuing characters, Eytinge has elected to depict Tupman (left), Snodgrass, and Winkle (right) just once, in this illustration facing chapter one, which inaugurates the Club and the reader's engagement in their disconnected "affairs." Although the American illustrator has accurately depicted these characters and their poses, he has in fact reversed their juxtaposition, so that Eytinge has foregrounded and isolated Tracy Tupman (the not-very-intelligent, but well-fed middle-aged, respectably dressed middle-class gentleman of receding hairline) to the left of Mr. Pickwick, who is standing (as in Robert Seymour's first illustration, "Mr. Pickwick Addresses the Club", April 1836) on a Windsor chair as he speaks enthusiastically about the activities of the Club and confronts the jealous Mr. Blotton (likely the figure standing at the opposite end of the table, up left). In preparing his sketches for the Harper and Brothers version of the Household Edition in the early 1870s, political cartoonist Thomas Nast may well have decided to utilise Eytinge's perspective rather than Seymour's. The moment depicted but adjusted is this:

And how much more interesting did the spectacle become, when, starting into full life and animation, as a simultaneous call for "Pickwick" burst from his followers, that illustrious man slowly mounted into the Windsor chair, on which he had been previously seated, and addressed the club himself had founded. What a study for an artist did that exciting scene present! The eloquent Pickwick, with one hand gracefully concealed behind his coat tails, and the other waving in air to assist his glowing declamation; his elevated position revealing those tights and gaiters, which, had they clothed an ordinary man, might have passed without observation, but which, when Pickwick clothed them — if we may use the expression &mdasah; inspired involuntary awe and respect; surrounded by the men who had volunteered to share the perils of his travels, and who were destined to participate in the glories of his discoveries. On his right sat Mr. Tracy Tupman; the too susceptible Tupman, who to the wisdom and experience of maturer years superadded the enthusiasm and ardour of a boy in the most interesting and pardonable of human weaknesses, — love. Time and feeding had expanded that once romantic form; the black silk waistcoat had become more and more developed; inch by inch had the gold watch-chain beneath it disappeared from within the range of Tupman's vision; and gradually had the capacious chin encroached upon the borders of the white cravat: but the soul of Tupman had known no change & mdash; admiration of the fair sex was still its ruling passion. On the left of his great leader sat the poetic Snodgrass, and near him again the sporting Winkle; the former poetically enveloped in a mysterious blue cloak with a canine-skin collar, and the latter communicating additional lustre to a new green shooting-coat, plaid neckerchief, and closely-fitted drabs.

Possibly because the engravings, whether on steel (Seymour's plate) or wood (Eytinge's), print in reverse, the figures in the negative are appropriately juxtaposed in each illustration. Whereas in the 1836 illustration the pictures in the background are of sporting events, Eytinge's single embedded illustration is of Stonehenge in Wiltshire, an indication that the artist decided to focus upon Pickwick as an antiquarian rather than the somewhat improbable founder of a Cockney sporting association. Like the Bronze Age ruin on the Salisbury Plain, the substantial Pickwick in tailcoat and gaiters, is a curiosity from a former age, the Regency, fast receding in memory by the 1860s.

The Pickwick Club

Chapter 1

Sol Eytinge Jr.

Diamond Edition 1867

Commentary:

In this initial full-page multiple-character study in the compact American "Diamond Edition," the principal members of Mr. Pickwick's club appear, as in the text:

'That the Corresponding Society of the Pickwick Club is therefore hereby constituted; and that Samuel Pickwick, Esq., G.C.M.P.C., Tracy Tupman, Esq., M.P.C., Augustus Snodgrass, Esq., M.P.C., and Nathaniel Winkle, Esq., M.P.C., are hereby nominated and appointed members of the same. . . . [ch. 1, p. 17 in The Diamond Edition]

In the longer programs of illustration — those by Seymour and Browne (1836-37), Browne in the British Household Edition (1873), and Nast in American Household Edition — these characters occur repeatedly. However, despite their importance as continuing characters, Eytinge has elected to depict Tupman (left), Snodgrass, and Winkle (right) just once, in this illustration facing chapter one, which inaugurates the Club and the reader's engagement in their disconnected "affairs." Although the American illustrator has accurately depicted these characters and their poses, he has in fact reversed their juxtaposition, so that Eytinge has foregrounded and isolated Tracy Tupman (the not-very-intelligent, but well-fed middle-aged, respectably dressed middle-class gentleman of receding hairline) to the left of Mr. Pickwick, who is standing (as in Robert Seymour's first illustration, "Mr. Pickwick Addresses the Club", April 1836) on a Windsor chair as he speaks enthusiastically about the activities of the Club and confronts the jealous Mr. Blotton (likely the figure standing at the opposite end of the table, up left). In preparing his sketches for the Harper and Brothers version of the Household Edition in the early 1870s, political cartoonist Thomas Nast may well have decided to utilise Eytinge's perspective rather than Seymour's. The moment depicted but adjusted is this:

And how much more interesting did the spectacle become, when, starting into full life and animation, as a simultaneous call for "Pickwick" burst from his followers, that illustrious man slowly mounted into the Windsor chair, on which he had been previously seated, and addressed the club himself had founded. What a study for an artist did that exciting scene present! The eloquent Pickwick, with one hand gracefully concealed behind his coat tails, and the other waving in air to assist his glowing declamation; his elevated position revealing those tights and gaiters, which, had they clothed an ordinary man, might have passed without observation, but which, when Pickwick clothed them — if we may use the expression &mdasah; inspired involuntary awe and respect; surrounded by the men who had volunteered to share the perils of his travels, and who were destined to participate in the glories of his discoveries. On his right sat Mr. Tracy Tupman; the too susceptible Tupman, who to the wisdom and experience of maturer years superadded the enthusiasm and ardour of a boy in the most interesting and pardonable of human weaknesses, — love. Time and feeding had expanded that once romantic form; the black silk waistcoat had become more and more developed; inch by inch had the gold watch-chain beneath it disappeared from within the range of Tupman's vision; and gradually had the capacious chin encroached upon the borders of the white cravat: but the soul of Tupman had known no change & mdash; admiration of the fair sex was still its ruling passion. On the left of his great leader sat the poetic Snodgrass, and near him again the sporting Winkle; the former poetically enveloped in a mysterious blue cloak with a canine-skin collar, and the latter communicating additional lustre to a new green shooting-coat, plaid neckerchief, and closely-fitted drabs.

Possibly because the engravings, whether on steel (Seymour's plate) or wood (Eytinge's), print in reverse, the figures in the negative are appropriately juxtaposed in each illustration. Whereas in the 1836 illustration the pictures in the background are of sporting events, Eytinge's single embedded illustration is of Stonehenge in Wiltshire, an indication that the artist decided to focus upon Pickwick as an antiquarian rather than the somewhat improbable founder of a Cockney sporting association. Like the Bronze Age ruin on the Salisbury Plain, the substantial Pickwick in tailcoat and gaiters, is a curiosity from a former age, the Regency, fast receding in memory by the 1860s.

Mr. Pickwick Addresses the Club

Chapter 1

Harold Copping

1924

Commentary:

This scene dated May 12, 1837 occurs when in the first installment Mr. Samuel Pickwick addresses the club to propose that it form a "corresponding society" which will travel about the country and report its finding to the entire club back in London. The travelling reporters (reminiscent of young Dickens himself in the 1832 election) are Pickwick himself, Tracy Tupman, Augustus Snodgrass, and Nathaniel Winkle.

Mr. Pickwick

Thomas Nast

1873 Household Edition

Commentary:

In the post-Civil War United States, two publishers both claimed to be Dickens's official licensees. In 1867 Ticknor and Fields of Boston acquired exclusive volume rights of reproduction, but Dickens still regarded Harper and Brothers of New York as his official serial publisher — as witnessed by his continuing to send the firm proof sheets from All the Year Round. Upon Dickens's death, exclusive publication rights appear to have devolved upon the house of Harper, which subsequently cast about for a suitable American artist to lead off the Household Edition in its copyright zone. The American illustrator whom Dickens most favored in the 1860s, Sol Eytinge, Jr., was out of the question, for he was one of Ticknor Fields' house artists.

The artist who had made a great name for himself recently through his political cartoons and Civil war illustrations, Thomas Nast, must naturally have come to Henry Harper's attention as exactly the sort of "big name" it could use to great effect in promoting the new joint venture with Chapman and Hall, despite the fact that, like Tenniel in England, Nast was a caricaturist rather than, like Phiz, an established illustrator of books. More to the point, he was already under contract to Harper and Brothers. However, the choice was not entirely inspired: since he was a political cartoonist rather than book illustrator, Nast tends to focus on Pickwick rather than realize significant moments in the narrative, so that one cannot call Nast's illustrations "realizations" of textual moments, which was still clearly Phiz's intention in his fifty-seven cuts for Chapman and Hall. Nast's program of cartoon-like illustrations is somewhat briefer: fifty-two.

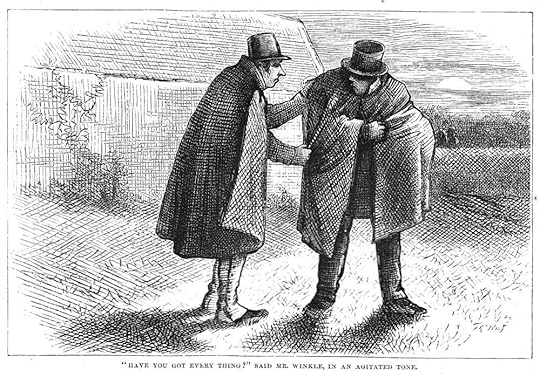

Have you got everything?

Chapter 2

Thomas Nast

1873 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

It was a dull and heavy evening when they again sallied forth on their awkward errand. Mr. Winkle was muffled up in a huge cloak to escape observation, and Mr. Snodgrass bore under his the instruments of destruction.

‘Have you got everything?’ said Mr. Winkle, in an agitated tone.

‘Everything,’ replied Mr. Snodgrass; ‘plenty of ammunition, in case the shots don’t take effect. There’s a quarter of a pound of powder in the case, and I have got two newspapers in my pocket for the loadings.’

These were instances of friendship for which any man might reasonably feel most grateful. The presumption is, that the gratitude of Mr. Winkle was too powerful for utterance, as he said nothing, but continued to walk on—rather slowly.

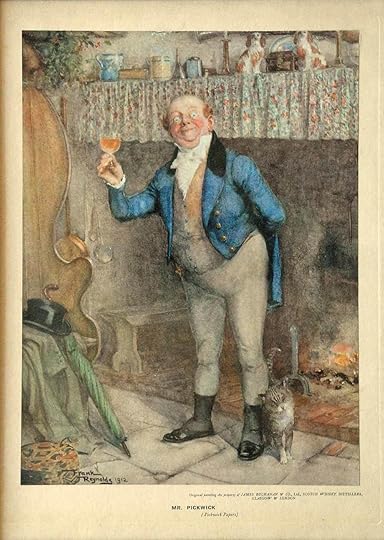

Mr. Pickwick

Frank Reynolds

Frank Reynolds was a British artist. Son of an artist, he studied at Heatherley's School of Art. Reynolds had a drawing called "A provincial theatre company on tour" published in "The Graphic" on November 30, 1901. In 1906 he began contributing to Punch Magazine and was regularly published within its pages during World War I. He was well known for his many illustrations in several books by Charles Dickens, including David Copperfield (c1911), The Pickwick Papers (c1912) and The Old Curiosity Shop (c1913). He succeeded F.H. Townsend as the Art Editor for Punch. He was also a prolific watercolour painter and was a member of the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours from 1903.

Reynolds was born in 1876, and gained fame for his humorous drawings in Punch, Sketch and The Illustrated London News. His specialty was caricaturization, and at the time, his drawings were described as being non-specific and even ugly. But with modern eyes, the clearness of compositions, economy of detail, and expressive caricature fit right in with what illustrators like Norman Rockwell were doing in the 40s and 50s. The books of Charles Dickens provided the perfect subject for Reynolds’ talents.

I wonder what Mr. Reynolds was thinking when he painted eyes?

Kim wrote: "Mr. Pickwick Addresses the Club

Chapter 1

Harold Copping

1924

Commentary:

This scene dated May 12, 1837 occurs when in the first installment Mr. Samuel Pickwick addresses the club to propose th..."

Kim

So many Pickwick’s to pick from. Thank goodness Pickwick’s first name is not Peter or Paul. We would have another “P” tongue-twister on our hands.

The commentary for this illustration suggestively links Dickens’s early travels around the country to the travels of the Pickwick Club. Never thought about that before. It makes sense.

Chapter 1

Harold Copping

1924

Commentary:

This scene dated May 12, 1837 occurs when in the first installment Mr. Samuel Pickwick addresses the club to propose th..."

Kim

So many Pickwick’s to pick from. Thank goodness Pickwick’s first name is not Peter or Paul. We would have another “P” tongue-twister on our hands.

The commentary for this illustration suggestively links Dickens’s early travels around the country to the travels of the Pickwick Club. Never thought about that before. It makes sense.

Kim wrote: "Mr. Pickwick

Frank Reynolds

Frank Reynolds was a British artist. Son of an artist, he studied at Heatherley's School of Art. Reynolds had a drawing called "A provincial theatre company on tour" p..."

Yes. The eyes are rather frightening for Pickwick, or anyone.

Frank Reynolds

Frank Reynolds was a British artist. Son of an artist, he studied at Heatherley's School of Art. Reynolds had a drawing called "A provincial theatre company on tour" p..."

Yes. The eyes are rather frightening for Pickwick, or anyone.

Did any of the illustrators draw a thin and tall Pickwick, as Dickens described him? Where did the idea of a portly Pickwick come from?

This is what I found (so far) about the appearance of Pickwick. It's from "The Life of Charles Dickens" by John Forster:

A young publishing-house had started recently, among other enterprises ingenious rather than important, a Library of Fiction; among the authors they wished to enlist in it was the writer of the sketches in the Monthly; and, to the extent of one paper during the past year, they had effected this through their editor, Mr. Charles Whitehead, a very ingenious and very unfortunate man. "I was not aware," wrote the elder member of the firm to Dickens, thirteen years later, in a letter to which reference was made in the preface to Pickwick in one of his later editions, "that you were writing in the Chronicle, or what your name was; but Whitehead, who was an old Monthly man, recollected it, and got you to write The Tuggs's at Ramsgate."

"In November, 1835," continues Mr. Chapman, "we published a little book called the Squib Annual, with plates by Seymour; and it was during my visit to him to see after them that he said he should like to do a series of cockney-sporting plates of a superior sort to those he had already published. I said I thought they might do, if accompanied by letter-press and published in monthly parts; and, this being agreed to, we wrote to the author of Three Courses and a Dessert, and proposed it; but, receiving no answer, the scheme dropped for some months, till Seymour said he wished us to decide, as another job had offered which would fully occupy his time; and it was on this we decided to ask you to do it. Having opened already a connection with you for our Library of Fiction, we naturally applied to you to do the Pickwick; but I do not think we even mentioned our intention to Mr. Seymour, and I am quite sure that from the beginning to the end nobody but yourself had anything whatever to do with it. Our prospectus was out at the end of February, and it had all been arranged before that date."

The member of the firm who carried the application to him in Furnival's Inn was not the writer of this letter, but Mr. Hall, who had sold him two years before, not knowing that he was the purchaser, the magazine in which his first effusion was printed; and he has himself described what passed at the interview: "The idea propounded to me was that the monthly something should be a vehicle for certain plates to be executed by Mr. Seymour; and there was a notion, either on the part of that admirable humorous artist, or of my visitor, that a Nimrod Club, the members of which were to go out shooting, fishing, and so forth, and getting themselves into difficulties through their want of dexterity, would be the best means of introducing these. I objected, on consideration that, although born and partly bred in the country, I was no great sportsman, except in regard to all kinds of locomotion; that the idea was not novel, and had already been much used; that it would be infinitely better for the plates to arise naturally out of the text; and that I would like to take my own way, with a freer range of English scenes and people, and was afraid I should ultimately do so in any case, whatever course I might prescribe to myself at starting. My views being deferred to, I thought of Mr. Pickwick, and wrote the first number; from the proof-sheets of which Mr. Seymour made his drawing of the club and his happy portrait of its founder. I connected Mr. Pickwick with a club, because of the original suggestion; and I put in Mr. Winkle expressly for the use of Mr. Seymour."

Mr. Hall was dead when this statement was first made, in the preface to the cheap edition in 1847; but Mr. Chapman clearly recollected his partner's account of the interview, and confirmed every part of it, in his letter of 1849, with one exception. In giving Mr. Seymour credit for the figure by which all the habitable globe knows Mr. Pickwick, and which certainly at the outset helped to make him a reality, it had given the artist too much. The reader will hardly be so startled as I was on coming to the closing line of Mr. Chapman's confirmatory letter: "As this letter is to be historical, I may as well claim what little belongs to me in the matter, and that is the figure of Pickwick. Seymour's first sketch was of a long, thin man. The present immortal one he made from my description of a friend of mine at Richmond, a fat old beau, who would wear, in spite of the ladies' protests, drab tights and black gaiters. His name was John Forster."

A young publishing-house had started recently, among other enterprises ingenious rather than important, a Library of Fiction; among the authors they wished to enlist in it was the writer of the sketches in the Monthly; and, to the extent of one paper during the past year, they had effected this through their editor, Mr. Charles Whitehead, a very ingenious and very unfortunate man. "I was not aware," wrote the elder member of the firm to Dickens, thirteen years later, in a letter to which reference was made in the preface to Pickwick in one of his later editions, "that you were writing in the Chronicle, or what your name was; but Whitehead, who was an old Monthly man, recollected it, and got you to write The Tuggs's at Ramsgate."

"In November, 1835," continues Mr. Chapman, "we published a little book called the Squib Annual, with plates by Seymour; and it was during my visit to him to see after them that he said he should like to do a series of cockney-sporting plates of a superior sort to those he had already published. I said I thought they might do, if accompanied by letter-press and published in monthly parts; and, this being agreed to, we wrote to the author of Three Courses and a Dessert, and proposed it; but, receiving no answer, the scheme dropped for some months, till Seymour said he wished us to decide, as another job had offered which would fully occupy his time; and it was on this we decided to ask you to do it. Having opened already a connection with you for our Library of Fiction, we naturally applied to you to do the Pickwick; but I do not think we even mentioned our intention to Mr. Seymour, and I am quite sure that from the beginning to the end nobody but yourself had anything whatever to do with it. Our prospectus was out at the end of February, and it had all been arranged before that date."

The member of the firm who carried the application to him in Furnival's Inn was not the writer of this letter, but Mr. Hall, who had sold him two years before, not knowing that he was the purchaser, the magazine in which his first effusion was printed; and he has himself described what passed at the interview: "The idea propounded to me was that the monthly something should be a vehicle for certain plates to be executed by Mr. Seymour; and there was a notion, either on the part of that admirable humorous artist, or of my visitor, that a Nimrod Club, the members of which were to go out shooting, fishing, and so forth, and getting themselves into difficulties through their want of dexterity, would be the best means of introducing these. I objected, on consideration that, although born and partly bred in the country, I was no great sportsman, except in regard to all kinds of locomotion; that the idea was not novel, and had already been much used; that it would be infinitely better for the plates to arise naturally out of the text; and that I would like to take my own way, with a freer range of English scenes and people, and was afraid I should ultimately do so in any case, whatever course I might prescribe to myself at starting. My views being deferred to, I thought of Mr. Pickwick, and wrote the first number; from the proof-sheets of which Mr. Seymour made his drawing of the club and his happy portrait of its founder. I connected Mr. Pickwick with a club, because of the original suggestion; and I put in Mr. Winkle expressly for the use of Mr. Seymour."

Mr. Hall was dead when this statement was first made, in the preface to the cheap edition in 1847; but Mr. Chapman clearly recollected his partner's account of the interview, and confirmed every part of it, in his letter of 1849, with one exception. In giving Mr. Seymour credit for the figure by which all the habitable globe knows Mr. Pickwick, and which certainly at the outset helped to make him a reality, it had given the artist too much. The reader will hardly be so startled as I was on coming to the closing line of Mr. Chapman's confirmatory letter: "As this letter is to be historical, I may as well claim what little belongs to me in the matter, and that is the figure of Pickwick. Seymour's first sketch was of a long, thin man. The present immortal one he made from my description of a friend of mine at Richmond, a fat old beau, who would wear, in spite of the ladies' protests, drab tights and black gaiters. His name was John Forster."

It's funny, but what the Pickwick Club most reminds me of is the modern day Elks Clubs in the USA.

It's funny, but what the Pickwick Club most reminds me of is the modern day Elks Clubs in the USA. Although the Elks Clubs are fixed facilities that cater to meetings, dances, and other gatherings -- I will duly note that in my experience, the largest "fixture" in any Elks Club I have been in, is the bar.

John wrote: "It's funny, but what the Pickwick Club most reminds me of is the modern day Elks Clubs in the USA.

Although the Elks Clubs are fixed facilities that cater to meetings, dances, and other gathering..."

It seems that the Pickwick Club would enjoy an evening with the Elks. No doubt, Winkle would make notes and perhaps write a poem celebrating the evening.

Although the Elks Clubs are fixed facilities that cater to meetings, dances, and other gathering..."

It seems that the Pickwick Club would enjoy an evening with the Elks. No doubt, Winkle would make notes and perhaps write a poem celebrating the evening.

Peter wrote: "John wrote: "It's funny, but what the Pickwick Club most reminds me of is the modern day Elks Clubs in the USA.

Peter wrote: "John wrote: "It's funny, but what the Pickwick Club most reminds me of is the modern day Elks Clubs in the USA. Although the Elks Clubs are fixed facilities that cater to meetings, dances, and ot..."

Peter, yes, it would work, and the beer taps would be flowing at the Elks Club for the Pickwickians.

The other thing that occurred to me about this book is it must be one of the earliest "travel" books. Maybe a few others before it, but travel literature is a favorite of mine, and I think the efforts of modern day writers who have dabbled in travel literature (the funny Bill Bryson comes to mind) owe something to Pickwick, even if their writings are non-fiction.

So many insightful comments by all of you since I last logged in, and so many new illlustrations posted by Kim! This is a good start for our new year's discussion.

When I saw the illustration by Seymour of Dr Slammer and the stranger with Mr Tupman on the stairs, I found it quite interesting what alterations Dickens had suggested. Apparently, Slammer's outspread arm was Dickens's idea, whereas Seymour had drawn the arm (with a clenched fist) in the air above the doctor's hat. Maybe, Dickens's version is indeed slightly more dramatic.

What impressed me more, however, is the difference in Mr Jingle's posture in the two illustrations. The older illustration shows Jingle with a slightly raised arm, which gives the impression of defensiveness, of being on the alert. The later illustration, though, shows Jingle leaning on the balustrade, his face, with an expression of mild boredom and condescension on it, turned towards the doctor, actually and literally looking down on him.

This posture seems to capture Mr Jingle's provocative manner, and his self-assuredness, much more aptly than the first posture, I think.

When I saw the illustration by Seymour of Dr Slammer and the stranger with Mr Tupman on the stairs, I found it quite interesting what alterations Dickens had suggested. Apparently, Slammer's outspread arm was Dickens's idea, whereas Seymour had drawn the arm (with a clenched fist) in the air above the doctor's hat. Maybe, Dickens's version is indeed slightly more dramatic.

What impressed me more, however, is the difference in Mr Jingle's posture in the two illustrations. The older illustration shows Jingle with a slightly raised arm, which gives the impression of defensiveness, of being on the alert. The later illustration, though, shows Jingle leaning on the balustrade, his face, with an expression of mild boredom and condescension on it, turned towards the doctor, actually and literally looking down on him.

This posture seems to capture Mr Jingle's provocative manner, and his self-assuredness, much more aptly than the first posture, I think.

Jess wrote: "What do you think of how Dickens manages to give a short characterization of each of the Pickwickians in this second chapter?

What can I add that has not been said? I fear I may find myself saying..."

Yes, the first chapter is quite a challenge, with its rather formal and grandiloquent style. The second chapter strikes a different tone, probably since it was all too obvious that Dickens could not have carried on the perspective and diction of the first chapter. It may be wondered which role the club is going to play in the course of the novel.

And do carry on reading, Jess! It's a wonderful novel!

What can I add that has not been said? I fear I may find myself saying..."

Yes, the first chapter is quite a challenge, with its rather formal and grandiloquent style. The second chapter strikes a different tone, probably since it was all too obvious that Dickens could not have carried on the perspective and diction of the first chapter. It may be wondered which role the club is going to play in the course of the novel.

And do carry on reading, Jess! It's a wonderful novel!

~ Cheryl ~ wrote: "Tristam wrote: I always understood "meaning something in the Pickwickian sense" as "meaning something in a way that is not meant to give offense", i.e. not in the sense the word in question is usua..."

Thanks for that information on the "Pickwickian sense", Cheryl. It's interesting to see in what different ways, Dickens managed to influence public life (and sometimes even improve conditions, as with "Oliver Twist").

Thanks for that information on the "Pickwickian sense", Cheryl. It's interesting to see in what different ways, Dickens managed to influence public life (and sometimes even improve conditions, as with "Oliver Twist").

Tristam wrote: So many insightful comments by all of you since I last logged in, and so many new illlustrations posted by Kim!...

Tristam wrote: So many insightful comments by all of you since I last logged in, and so many new illlustrations posted by Kim!...What impressed me more, however, is the difference in Mr Jingle's posture in the two illustrations.

I am also thankful for all the illustrations posted by Kim.

And I also particularly noticed the differences in Mr. Jingle's stance in the two sketches. I had the same thought, that the second one seemed to show he was being antagonistic by being sort of passive-aggressive, like standing there coolly leaning on the banister not complying with Slammer, making Slammer more infuriated.

I LOVE looking at all the illustrations. Dickens's writing is so vivid already, yet the illustrations somehow make it even more magical.

John wrote: "The other thing that occurred to me about this book is it must be one of the earliest "travel" books. ...and I think the efforts of modern day writers who have dabbled in travel literature (the funny Bill Bryson comes to mind) owe something to Pickwick, even if their writings are non-fiction.

John wrote: "The other thing that occurred to me about this book is it must be one of the earliest "travel" books. ...and I think the efforts of modern day writers who have dabbled in travel literature (the funny Bill Bryson comes to mind) owe something to Pickwick, even if their writings are non-fiction.Good point!

Tristram wrote: "So many insightful comments by all of you since I last logged in, and so many new illlustrations posted by Kim! This is a good start for our new year's discussion.

When I saw the illustration by S..."

Tristram

Yes. I see it too. Thanks for the observation. Body language often speaks as loudly as one’s tongue.

When I saw the illustration by S..."

Tristram

Yes. I see it too. Thanks for the observation. Body language often speaks as loudly as one’s tongue.

~ Cheryl ~ wrote: "Tristam wrote: So many insightful comments by all of you since I last logged in, and so many new illlustrations posted by Kim!...

What impressed me more, however, is the difference in Mr Jingle's ..."

Hi Cheryl

If you enjoyed the initial illustrations you will find our discussions a constant delight. Kim’s constant posts keep us in touch with the illustrations and the commentaries each week.

What impressed me more, however, is the difference in Mr Jingle's ..."

Hi Cheryl

If you enjoyed the initial illustrations you will find our discussions a constant delight. Kim’s constant posts keep us in touch with the illustrations and the commentaries each week.

Tristram wrote: "...Let’s now turn over the first page of Dickens’s first novel,.."

Several posts have called PP a novel.

I beg to differ. I don't think it's a novel. What it is, I'm not sure, but a novel it's not.

Several posts have called PP a novel.

I beg to differ. I don't think it's a novel. What it is, I'm not sure, but a novel it's not.

Everyman wrote: "Tristram wrote: "...Let’s now turn over the first page of Dickens’s first novel,.."

Several posts have called PP a novel.

I beg to differ. I don't think it's a novel. What it is, I'm not sure, bu..."

Hi Everyman

How about Episodic Novel or Picaresque Novel? I too find the first two chapters somewhat like sketches. Then again, perhaps the phrase “just a darn good read” would work ... for now. [g]

Several posts have called PP a novel.

I beg to differ. I don't think it's a novel. What it is, I'm not sure, bu..."

Hi Everyman

How about Episodic Novel or Picaresque Novel? I too find the first two chapters somewhat like sketches. Then again, perhaps the phrase “just a darn good read” would work ... for now. [g]

From the critics I've read over the years, and also from the biographies of Dickens, qualifying what Pickwick really is has not brought about agreement. Obviously I'm not far enough long myself to make a judgment. If all novels have one element, it is probably "closure." So, we'll see.

From the critics I've read over the years, and also from the biographies of Dickens, qualifying what Pickwick really is has not brought about agreement. Obviously I'm not far enough long myself to make a judgment. If all novels have one element, it is probably "closure." So, we'll see.

Everyman wrote: "Several posts have called PP a novel. I beg to differ. I don't think it's a novel..."

Everyman wrote: "Several posts have called PP a novel. I beg to differ. I don't think it's a novel..."I agree with Peter :)

This is something I considered when I first started my personal Dickens challenge to read all his novel again, in order, back in 2013 (a little while before I met the lovely crowd here :) ). Where to start? My "centennial edition" didn't really help, as apart from his letters it contains almost everything by him which is still published.

Two additional thoughts:

1. Does the author's original intention matter? Clearly, since we know its history there was no "plan" for The Pickwick Papers to become what we now call a novel. It is only in retrospect that we class it as such.

Many here are are more familiar with 18th century novels than I, but I think it was only in the 19th century, and the Victorians, that our more rigidly defined view of what constitutes a novel, eg. in-depth portrayals of characters and their motivations etc. was refined. Before that, they were more like episodic adventures, with picaresque tales being very popular.

Perhaps because in retrospect we can now see how Dickens developed, we view the linked episodes of The Pickwick Papers, with characters in common, as the true starting point for his later novels.

2. From Penguin Classics, and the Goodreads book page:

"Few first novels have created as much popular excitement as The Pickwick Papers–-a comic masterpiece..."

For convenience, I usually go with how publishers class their books. The Pickwick Papers usually makes it into novel status, and the one which preceded it, Sketches by Boz is conventionally placed in "miscellaneous writings" along with American Notes For General Circulation, Pictures from Italy etc.

I go along with different publishers' definitions of what constitutes a classic too. (Or for the purposes of Goodreads, what the readers think, as evidenced by the stats on the book page.) Otherwise, with all the differences of opinion between critics, it's possible to get bogged down in cut-off dates etc.

I have a question:

I have a question:Who is supposed to be narrating these chapters (the whole book)?

Is it the "secretary" who wrote the minutes of the first chapter?

Do we know his name?

I have always thought of Don Quixote as being the first, or at least one of the first novels written (limiting myself to European and American literature, my knowledge being limited to those), and Cervantes's book does not really give an plot with an overarching frame and intricate cross-references but rather a series of loosely-connected events all more or less linked with Don Quixote and his companion Sancho Pansa. In PP we have a string of events linked with Don Pickwick and his friends. If I remember Don Quixote correctly, we even have at least one tale within the novel, maybe more, as we also find lots of tales immersed in the fabric of the picaresque adventures of our Pickwickian friends.

Fielding's and Smollet's novels are similar in structure to Don Quixote, and I think Dickens had read a lot of their books and was probably influenced by their style. The pattern of serialization in which PP was published further encouraged Dickens to write in episodes for PP.

Still, I would call this book a novel because it is a long narrative text. I would also call it a masterpiece, but that's a horse of a different colour.

Fielding's and Smollet's novels are similar in structure to Don Quixote, and I think Dickens had read a lot of their books and was probably influenced by their style. The pattern of serialization in which PP was published further encouraged Dickens to write in episodes for PP.

Still, I would call this book a novel because it is a long narrative text. I would also call it a masterpiece, but that's a horse of a different colour.

~ Cheryl ~ wrote: "I have a question:

Who is supposed to be narrating these chapters (the whole book)?

Is it the "secretary" who wrote the minutes of the first chapter?

Do we know his name?"

From several passages in the first few chapters, I gain the impression that the narrator adopts the role of some kind of chronicler sifting the papers of the Pickwick Club in order to present to his readers a picture of the achievements of the Pickwickians. In the course of the action, however, this chronicler becomes more and more of an omniscient narrator.

Who is supposed to be narrating these chapters (the whole book)?

Is it the "secretary" who wrote the minutes of the first chapter?

Do we know his name?"

From several passages in the first few chapters, I gain the impression that the narrator adopts the role of some kind of chronicler sifting the papers of the Pickwick Club in order to present to his readers a picture of the achievements of the Pickwickians. In the course of the action, however, this chronicler becomes more and more of an omniscient narrator.

Tristram wrote: "I have always thought of Don Quixote as being the first, or at least one of the first novels written (limiting myself to European and American literature, my knowledge being limited to..."

Tristram wrote: "I have always thought of Don Quixote as being the first, or at least one of the first novels written (limiting myself to European and American literature, my knowledge being limited to..."I've seen Pickwick classified as a novel, but have also seen Oliver Twist identified as Dickens's first novel.

I'm having difficulty thinking of 18th c novels that don't have a consistent plot thread. For instance Robinson Crusoe feels very episodic and sometimes kind of random, but it's organized at least on its title page as the story of a guy who got shipwrecked and rescued (though the actually execution is a little looser than that). I can't remember Pickwick well enough to recall whether it has a plot thread. Since it was published serially, that might have been something that began to emerge as the installments came out, much as television series will sometimes develop ongoing plot arcs as people get to know the characters and their dilemmas/relationships.

I'm skeptical of how modern publishers label their books because their job is to sell books and novels tend to sell better than story collections. I've seen some contemporary works labeled novels that really don't have a continuous narrative at all, not even a scrambled one, for instance this book (which is excellent, despite IMO not being a novel): The Lost Books of The Odyssey

Tristram wrote: "I have always thought of Don Quixote as being the first, or at least one of the first novels written (limiting myself to European and American literature, my knowledge being limited to..."

Tristram wrote: "I have always thought of Don Quixote as being the first, or at least one of the first novels written (limiting myself to European and American literature, my knowledge being limited to..."Thinking now about the Don Quixote-Smollet--Fielding model and while I haven't read Smollet I'd still say the string-of-events book still has a plot as long as it's framed by a continuous narrative in which the characters are dealing with issues that are not resolved in each installment.

Julie wrote: "I've seen some contemporary works labeled novels that really don't have a continuous narrative at all, ..."

Julie wrote: "I've seen some contemporary works labeled novels that really don't have a continuous narrative at all, ..."Yes, clearly this is unacceptable, and done merely for commercial reasons.

I think the crux here is "continuous narrative". If it's possible to tell the broad story of a novel in a couple of sentences, then that's another quick rule of thumb. It was the differences between individual critic's definitions I was trying to avoid.

Thanks for the examples of 18th century novels, Tristram. Those are exactly what I had in mind, as being Dickens's main influences, so I'm glad you could confirm this.

As to Don Quixote, if I remember it well there is a longer love story inside that does not really have any immediate relation to the main story. The main story is basically a series - our hero is sometimes taken home by his friends - of knight errand excursions consisting of adventures that have no strong connections with each other. The famous windmill scene, for example, is told on one or two pages.

I find Pickwick interestingly similar to DQ in that here, too, we have the journey motif which serves as a way of introducing shorter adventures. At least one of these adventures will be of more consequence for the story as such, stretching over a number of individual instalments. Unlike in DQ, in Pickwick we also have a greater number of recurring characters although a lot of the characters (this is not very typical of Dickens, who would later always reintroduce his characters in different parts of his stories) only make appearances in one episode.

All in all, I would still consider Pickwick a novel.

I find Pickwick interestingly similar to DQ in that here, too, we have the journey motif which serves as a way of introducing shorter adventures. At least one of these adventures will be of more consequence for the story as such, stretching over a number of individual instalments. Unlike in DQ, in Pickwick we also have a greater number of recurring characters although a lot of the characters (this is not very typical of Dickens, who would later always reintroduce his characters in different parts of his stories) only make appearances in one episode.

All in all, I would still consider Pickwick a novel.

Phiz and the 1874 Household Edition

Hoping to capitalise on the early 1870s nostalgia for all things Dickens, Chapman and Hall decided to bring out a wholly new edition of Dickens's works in a uniform, two-column format, thereby capitalising on American and British continued respect for Household Words. They chose this format despite the fact that it required extensive programs of illustration by contemporary artists. Instead of saving money by commissioning relatively unknown illustrators such as Fred Barnard, Chapman and Hall instead opted in 1872 for an artist who would immediately arouse wide-spread public interest in the new edition — Phiz (Hablot Knight Browne), whom Dickens's adoring readers fondly remembered as the great writer's co-presenter in a string of novels spanning Dickens's career, from The Pickwick Papers in 1836 to A Tale of Two Cities in 1859. Despite suffering a paralytic stroke in 1867 while on a seaside holiday, Browne remained productive and inventive. If Valerie Browne Lester has correctly dated the Chapman and Hall commission to 1871, then we must assume that Browne's pace of composition was indeed leisurely, even glacial, compared to his former output — the result of the loss of sight in his right eye and loss of full function in his right hand. She lists nothing again until 1875, by which point Phiz had regained most of the use of his right hand.

Clearly Chapman and Hall's was a huge commission for an artist with failing health and eyesight, but his name was almost iconic, even in 1873, so that Chapman and Hall must have counted on his "bankability" (as Hollywood would have it) to launch the new, expensive venture. Although no stranger to the woodcut, Phiz was best remembered for his steel engravings in the novels of Dickens and Lever. Therefore, redrafting many of his original Pickwick illustrations as woodcuts, was something of a gamble — even more so because they now had (a) a horizontal orientation a full-page wide, but now only one-third-of-page high. Robert L. Patten (1978), Michael Steig (1978), and Jane Rabb Cohen (1980) do not speculate as to why Phiz, whose style was markedly old fashioned when compared to the new realism of the Sixties illustrators, should have received the commission when Chapman and Hall already had Fred Barnard under contract. As Paul Davis says, "by 1860 Browne's style, grounded in the graphic-satiric tradition of Hogarth, was no longer appropriate", and we cannot deem his attempt to re-do his etchings as woodcuts entirely successful, but at least they take us where Steig does not, to an appreciation of his final major commission after which the 1867 paralysis often prevented him from working during the last nine years of his life. Phiz's last significant commission came in 1875 for one hundred designs for the new "Harry Lorrequer" edition of Lever's works, to be issued by Routledge between 1876 and 1878. Perhaps Routledge, like Champan and Hall, recognized that Phiz's post-1867 drawings, "while broad and clumsy compared to the elegance of his work in the 1840s and 1850s, show verve, swing, and rollicking humor". Only months after his stroke, “indomitably he struggled back to the grind of illustration and it seems incredible that, so short a time after what should have been a crippling illness, he could be producing work that is by no means despicable”.

Although perhaps not perhaps so great an artist as George Cruikshank, Phiz remained welded to Dickens in the minds of readers in England, although he had illustrated nothing by the great writer since late 1859. The choice of initial illustrator for Chapman and Hall's version of the Household edition of Pickwick must have seemed inevitable, despite the decline in both the quality and output of his work as a result of that mysterious paralysis of 1867. Phiz was still the necessary adjunct, especially to the early "Boz."

Hoping to capitalise on the early 1870s nostalgia for all things Dickens, Chapman and Hall decided to bring out a wholly new edition of Dickens's works in a uniform, two-column format, thereby capitalising on American and British continued respect for Household Words. They chose this format despite the fact that it required extensive programs of illustration by contemporary artists. Instead of saving money by commissioning relatively unknown illustrators such as Fred Barnard, Chapman and Hall instead opted in 1872 for an artist who would immediately arouse wide-spread public interest in the new edition — Phiz (Hablot Knight Browne), whom Dickens's adoring readers fondly remembered as the great writer's co-presenter in a string of novels spanning Dickens's career, from The Pickwick Papers in 1836 to A Tale of Two Cities in 1859. Despite suffering a paralytic stroke in 1867 while on a seaside holiday, Browne remained productive and inventive. If Valerie Browne Lester has correctly dated the Chapman and Hall commission to 1871, then we must assume that Browne's pace of composition was indeed leisurely, even glacial, compared to his former output — the result of the loss of sight in his right eye and loss of full function in his right hand. She lists nothing again until 1875, by which point Phiz had regained most of the use of his right hand.

Clearly Chapman and Hall's was a huge commission for an artist with failing health and eyesight, but his name was almost iconic, even in 1873, so that Chapman and Hall must have counted on his "bankability" (as Hollywood would have it) to launch the new, expensive venture. Although no stranger to the woodcut, Phiz was best remembered for his steel engravings in the novels of Dickens and Lever. Therefore, redrafting many of his original Pickwick illustrations as woodcuts, was something of a gamble — even more so because they now had (a) a horizontal orientation a full-page wide, but now only one-third-of-page high. Robert L. Patten (1978), Michael Steig (1978), and Jane Rabb Cohen (1980) do not speculate as to why Phiz, whose style was markedly old fashioned when compared to the new realism of the Sixties illustrators, should have received the commission when Chapman and Hall already had Fred Barnard under contract. As Paul Davis says, "by 1860 Browne's style, grounded in the graphic-satiric tradition of Hogarth, was no longer appropriate", and we cannot deem his attempt to re-do his etchings as woodcuts entirely successful, but at least they take us where Steig does not, to an appreciation of his final major commission after which the 1867 paralysis often prevented him from working during the last nine years of his life. Phiz's last significant commission came in 1875 for one hundred designs for the new "Harry Lorrequer" edition of Lever's works, to be issued by Routledge between 1876 and 1878. Perhaps Routledge, like Champan and Hall, recognized that Phiz's post-1867 drawings, "while broad and clumsy compared to the elegance of his work in the 1840s and 1850s, show verve, swing, and rollicking humor". Only months after his stroke, “indomitably he struggled back to the grind of illustration and it seems incredible that, so short a time after what should have been a crippling illness, he could be producing work that is by no means despicable”.

Although perhaps not perhaps so great an artist as George Cruikshank, Phiz remained welded to Dickens in the minds of readers in England, although he had illustrated nothing by the great writer since late 1859. The choice of initial illustrator for Chapman and Hall's version of the Household edition of Pickwick must have seemed inevitable, despite the decline in both the quality and output of his work as a result of that mysterious paralysis of 1867. Phiz was still the necessary adjunct, especially to the early "Boz."

"Come on," said the cab-driver, sparring away like clockwork. "Come on — all four of you."

Chapter 2

Phiz

1874 Household Edition

Commentary:

Phiz vigorously reinterprets Seymour's "The Pugnacious Cabman" in this uncaptioned 1873 illustration that leads off the second chapter. Oddly enough, Phiz has minimized the background, including the Regency blocks of flats in Seymour's original, as he has focused on the confrontation of a terrified Pickwick (right centre) and a very sturdy cabman (left centre), whereas Seymour had made a rather belligerent Pickwick the larger of the two figures (left) and had given the hot pie-man greater prominence. With no visual tradition as a context, Seymour had shown Pickwick in a buttoned-up "duster," whereas Phiz has given us the familiar figure of the tailcoated, rotund figure of Pickwick in his habitual white waistcoat.

Seymour's illustration:

What! Introducing his friend?

Chapter 2

Phiz

1874 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

‘I’ll dance with the widow,’ said the stranger.

‘Who is she?’ inquired Mr. Tupman.

‘Don’t know—never saw her in all my life—cut out the doctor—here goes.’ And the stranger forthwith crossed the room; and, leaning against a mantel-piece, commenced gazing with an air of respectful and melancholy admiration on the fat countenance of the little old lady. Mr. Tupman looked on, in mute astonishment. The stranger progressed rapidly; the little doctor danced with another lady; the widow dropped her fan; the stranger picked it up, and presented it—a smile—a bow—a curtsey—a few words of conversation. The stranger walked boldly up to, and returned with, the master of the ceremonies; a little introductory pantomime; and the stranger and Mrs. Budger took their places in a quadrille.

The surprise of Mr. Tupman at this summary proceeding, great as it was, was immeasurably exceeded by the astonishment of the doctor. The stranger was young, and the widow was flattered. The doctor’s attentions were unheeded by the widow; and the doctor’s indignation was wholly lost on his imperturbable rival. Doctor Slammer was paralysed. He, Doctor Slammer, of the 97th, to be extinguished in a moment, by a man whom nobody had ever seen before, and whom nobody knew even now! Doctor Slammer—Doctor Slammer of the 97th rejected! Impossible! It could not be! Yes, it was; there they were. What! introducing his friend! Could he believe his eyes! He looked again, and was under the painful necessity of admitting the veracity of his optics; Mrs. Budger was dancing with Mr. Tracy Tupman; there was no mistaking the fact. There was the widow before him, bouncing bodily here and there, with unwonted vigour; and Mr. Tracy Tupman hopping about, with a face expressive of the most intense solemnity, dancing (as a good many people do) as if a quadrille were not a thing to be laughed at, but a severe trial to the feelings, which it requires inflexible resolution to encounter.

Commentary:

Having connected the reader with one of the original serial's earliest illustrations — "The Pugnacious Cabman" by Seymour — Phiz now presents a scene that Dickens's first Pickwick illustrator never attempted: the social gathering of the select families and military notables in a garrison town on the first Pickwickian journey in the second chapter of the novel. Wisely, Seymour focused on the comic possibilities of mistaken identities arising from Dr. Slammer's challenging the stranger (dressed in Winkle's club suit) to a duel, for which Seymour's "Dr. Slammer's Defiance" (April 1836) prepares us much better than this Household Edition illustration of Tupman and the "Stranger" being introduced to Mrs. Budger (right) at the charity ball. However, the man ("with a ring of upright black hair,") looking angrily back over his shoulder at the outsiders and (and at the rich widow upon whom he has had designs for some time) is almost certainly Dr. Slammer, surgeon to the Ninety-seventh regiment, from whose perspective Dickens momentarily narrates the scene.

Nevertheless, Phiz establishes the context of the quarrel between Slammer and the stranger — the charity ball — rather better than Seymour. Seymour chose the scene with great dramatic potential, but failed to exploit the comic possibilities as his successor, Phiz, undoubtedly would have done. But neither artist makes explicit the setting, the ballroom upstairs in the Bull Inn, at the top of the High Street in Rochester. According to Cohen, Seymour was put out by Dickens's so swiftly shifting the action from London, a milieu so well known to Seymour, to the Medway's four towns (Strood, Rochester, Chatham, and Brompton), none of which he had ever visited.

I find it odd that Seymour would have objected to Dickens taking the action from London into the country, he being such an outdoorsman, how much fishing, hunting, and the like could you do in London?

I started reflecting on the full title of this work -- The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club.

That tells us that at some point there is going to be a death, or ending. Is Dickens telling us that the Pickwick Club will be dissolved before the end of the book? If so, one has to speculate how and why. Or is Pickwick himself going to die before these papers are published? Interesting that at the very start of the project Dickens is already telling us that something or somebody is going to meet their end before the book is done.

That tells us that at some point there is going to be a death, or ending. Is Dickens telling us that the Pickwick Club will be dissolved before the end of the book? If so, one has to speculate how and why. Or is Pickwick himself going to die before these papers are published? Interesting that at the very start of the project Dickens is already telling us that something or somebody is going to meet their end before the book is done.

Everyman wrote: "I started reflecting on the full title of this work -- The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club.

Everyman wrote: "I started reflecting on the full title of this work -- The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club.That tells us that at some point there is going to be a death, or ending. Is Dickens telling us t..."

However, could it simply be the author's intent to inform the reader that these stories and activities originate from the past rather than pointing to a death? I sense an affinity to your second suggestion, but who knows where Dickens will take us?

I have always thought that the title insinuates that we, as readers, get to partake of the special activities of the club? Activities from the past. Perchance in a similar fashion as finding an old journal in a box in one's attic?

Haaze wrote: "Everyman wrote: "I started reflecting on the full title of this work -- The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club.

That tells us that at some point there is going to be a death, or ending. Is Dic..."

Everyman and Haaze

What an interesting conversation. It is important to look at the entire title to understand the text and you both have got me thinking in a new direction. Yes, the word “posthumous” does weigh heavily on the title, and thus our approach to the concept of the text.

I like Haaze’s interpretation that the papers are from the past. As we have seen in the first two chapters there is much made of the recording of the Pickwick Club’s meetings, and it seems that their adventures and encounters all come to be recorded as well.

Since written material is meant to record events from the past or present in order to preserve and document that past or present for the future, then this title could well suggest what happened in the past. Sadly, that would suggest that our Pickwickians friends have passed.

On the other hand, and now I’m disagreeing with myself, the setting of the novel and the time it is being written are very close together. No great time differential as we see in Dickens’s “historical” novels such as BR or TTC. Indeed, many novel of Dickens have a time gap of some decades between their written date and their setting. GE would be an example.

Lots to consider from the title. Thanks.

That tells us that at some point there is going to be a death, or ending. Is Dic..."

Everyman and Haaze

What an interesting conversation. It is important to look at the entire title to understand the text and you both have got me thinking in a new direction. Yes, the word “posthumous” does weigh heavily on the title, and thus our approach to the concept of the text.

I like Haaze’s interpretation that the papers are from the past. As we have seen in the first two chapters there is much made of the recording of the Pickwick Club’s meetings, and it seems that their adventures and encounters all come to be recorded as well.

Since written material is meant to record events from the past or present in order to preserve and document that past or present for the future, then this title could well suggest what happened in the past. Sadly, that would suggest that our Pickwickians friends have passed.

On the other hand, and now I’m disagreeing with myself, the setting of the novel and the time it is being written are very close together. No great time differential as we see in Dickens’s “historical” novels such as BR or TTC. Indeed, many novel of Dickens have a time gap of some decades between their written date and their setting. GE would be an example.

Lots to consider from the title. Thanks.

From John Forster's The Life of Charles Dickens:

His new story was now beginning largely to share attention with his Pickwick Papers, and it was delightful to see how real all its people became to him. What I had most, indeed, to notice in him, at the very outset of his career, was his indifference to any praise of his performances on the merely literary side, compared with the higher recognition of them as bits of actual life, with the meaning and purpose on their part, and the responsibility on his, of realities rather than creatures of fancy. The exception that might be drawn from Pickwick is rather in seeming than substance. A first book has its immunities, and the distinction of this from the rest of the writings appears in what has been said of its origin. The plan of it was simply to amuse. It was to string together whimsical sketches of the pencil by entertaining sketches of the pen; and, at its beginning, where or how it was to end was as little known to himself as to any of its readers. But genius is a master as well as a servant, and when the laughter and fun were at their highest something graver made its appearance. He had to defend himself for this; and he said that, though the mere oddity of a new acquaintance was apt to impress one at first, the more serious qualities were discovered when we became friends with the man. In other words he might have said that the change was become necessary for his own satisfaction. The book itself, in teaching him what his power was, had made him more conscious of what would be expected from its use; and this never afterwards quitted him. In what he was to do hereafter, as in all he was doing now, with Pickwick still to finish and Oliver only beginning, it constantly attended him.

His new story was now beginning largely to share attention with his Pickwick Papers, and it was delightful to see how real all its people became to him. What I had most, indeed, to notice in him, at the very outset of his career, was his indifference to any praise of his performances on the merely literary side, compared with the higher recognition of them as bits of actual life, with the meaning and purpose on their part, and the responsibility on his, of realities rather than creatures of fancy. The exception that might be drawn from Pickwick is rather in seeming than substance. A first book has its immunities, and the distinction of this from the rest of the writings appears in what has been said of its origin. The plan of it was simply to amuse. It was to string together whimsical sketches of the pencil by entertaining sketches of the pen; and, at its beginning, where or how it was to end was as little known to himself as to any of its readers. But genius is a master as well as a servant, and when the laughter and fun were at their highest something graver made its appearance. He had to defend himself for this; and he said that, though the mere oddity of a new acquaintance was apt to impress one at first, the more serious qualities were discovered when we became friends with the man. In other words he might have said that the change was become necessary for his own satisfaction. The book itself, in teaching him what his power was, had made him more conscious of what would be expected from its use; and this never afterwards quitted him. In what he was to do hereafter, as in all he was doing now, with Pickwick still to finish and Oliver only beginning, it constantly attended him.

From "Appreciations and Criticisms of the Works of Charles Dickens" by G.K. Chesterton:

The whole difference between construction and creation is exactly this: that a thing constructed can only be loved after it is constructed; but a thing created is loved before it exists, as the mother can love the unborn child. In creative art the essence of a book exists before the book or before even the details or main features of the book; the author enjoys it and lives in it with a kind of prophetic rapture. He wishes to write a comic story before he has thought of a single comic incident. He desires to write a sad story before he has thought of anything sad. He knows the atmosphere before he knows anything. There is a low priggish maxim sometimes uttered by men so frivolous as to take humor seriously—a maxim that a man should not laugh at his own jokes. But the great artist not only laughs at his own jokes; he laughs at his own jokes before he has made them. In the case of a man really humorous we can see humor in his eye before he has thought of any amusing words at all. So the creative writer laughs at his comedy before he creates it, and he has tears for his tragedy before he knows what it is. When the symbols and the fulfilling facts do come to him, they come generally in a manner very fragmentary and inverted, mostly in irrational glimpses of crisis or consummation. The last page comes before the first; before his romance has begun, he knows that it has ended well. He sees the wedding before the wooing; he sees the death before the duel. But most of all he sees the color and character of the whole story prior to any possible events in it. This is the real argument for art and style, only that the artists and the stylists have not the sense to use it. In one very real sense style is far more important than either character or narrative. For a man knows what style of book he wants to write when he knows nothing else about it.