The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Our Mutual Friend

Our Mutual Friend

>

OMF, Book 3, Chp. 11 - 14

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Chapter 12 is titled "Meaning Mischief" and we have left Bradley and Riderhood with their plots to drop in on the Lammle's, who are at this moment having breakfast:

‘It seems to me,’ said Mrs Lammle, ‘that you have had no money at all, ever since we have been married.’

‘What seems to you,’ said Mr Lammle, ‘to have been the case, may possibly have been the case. It doesn’t matter.’

Was it the speciality of Mr and Mrs Lammle, or does it ever obtain with other loving couples? In these matrimonial dialogues they never addressed each other, but always some invisible presence that appeared to take a station about midway between them. Perhaps the skeleton in the cupboard comes out to be talked to, on such domestic occasions?

‘I have never seen any money in the house,’ said Mrs Lammle to the skeleton, ‘except my own annuity. That I swear.’

‘You needn’t take the trouble of swearing,’ said Mr Lammle to the skeleton; ‘once more, it doesn’t matter. You never turned your annuity to so good an account.’

During this breakfast talk we learn that the Lammles are about to "smash" as Mr. Lammle puts it. I can't remember how long these two have been married, but I don't know how they got this far without "smashing" a long time ago. How two people with no money manage to put food on the table is beyond me. And they also have a servant, how do they pay for a servant? We now find that Mr. Lammle has given a Jew a bill of sale on the furniture, and the Jew would have collected the furniture long ago if it hadn't been for Fledgeby. I'm assuming that the person really behind this bill of sale is Fledgeby in the first place, so what is he doing? He must have known their financial situation so why did he give them the money?

This chapter ended an idea I've had since we met the Lammles. And it's all because of you all that I thought this way at all. I've read the book a few times before and never considered Mr. Lammle was beating his wife until some of you mentioned it and then I thought you seemed right, no wonder she seemed to be afraid of him, but Dickens ends that idea with this;

"As Lammle, standing gathering up the skirts of his dressing-gown with his back to the fire, said this, looking down at his wife, she turned pale and looked down at the ground. With a sense of disloyalty upon her, and perhaps with a sense of personal danger—for she was afraid of him—even afraid of his hand and afraid of his foot, though he had never done her violence—she hastened to put herself right in his eyes."

So, if he has never done her physical harm why is she so afraid of him? Can she see that he would harm her if she pushed him too far? Now they discuss their future, how they can save themselves from being poor and homeless that is, and come up with a plan.

‘It is natural, Alfred,’ she said, looking up with some timidity into his face, ‘to think in such an emergency of the richest people we know, and the simplest.’

‘Just so, Sophronia.’

‘The Boffins.’

‘Just so, Sophronia.’

‘Is there nothing to be done with them?’

‘What is there to be done with them, Sophronia?’

She cast about in her thoughts again, and he kept his eye upon her as before.

‘Of course I have repeatedly thought of the Boffins, Sophronia,’ he resumed, after a fruitless silence; ‘but I have seen my way to nothing. They are well guarded. That infernal Secretary stands between them and—people of merit.’

‘If he could be got rid of?’ said she, brightening a little, after more casting about."

Their plan is to get rid of the secretary by turning Mr. Boffin against him. Mrs. Lammle is going to go to the Boffins telling them she cannot be silent on the actions of Rokesmith, believing that if they tell Mr. Boffin of Rokesmith's interest in Bella, and that he had made an offer to her, Mr. Boffin would be sure to dismiss him;

‘‘Suppose I so repeated it to Mr Boffin, as to insinuate that my sensitive delicacy and honour—’

‘Very good words, Sophronia.’

‘—As to insinuate that our sensitive delicacy and honour,’ she resumed, with a bitter stress upon the phrase, ‘would not allow us to be silent parties to so mercenary and designing a speculation on the Secretary’s part, and so gross a breach of faith towards his confiding employer. Suppose I had imparted my virtuous uneasiness to my excellent husband, and he had said, in his integrity, “Sophronia, you must immediately disclose this to Mr Boffin.”’

‘Once more, Sophronia,’ observed Lammle, changing the leg on which he stood, ‘I rather like that.’

At this time Fledgeby shows up at the door and Alfred leaves the room leaving his wife to deal with Fledgeby on her own. She tells Fledgeby that Alfred isn't there, that being so worried about their finances he left the house early. I'm wondering if she is attempting to get Fledgeby believe that Alfred is out trying to find some sort of employment. I can't quite picture Lammle doing any "real work". She asks Fledgeby if he can once again use his influence over Riah giving them more time to pay the bill,

‘Oh!’ said Fledgeby. ‘Then you think, Mrs Lammle, that if Lammle got time, he wouldn’t burst up?—To use an expression,’ Mr Fledgeby apologetically explained, ‘which is adopted in the Money Market.’

‘Indeed yes. Truly, truly, yes!’

‘That makes all the difference,’ said Fledgeby. ‘I’ll make a point of seeing Riah at once."

And now Fledgeby is off to see Riah and ask him to give the Lammles more time. Right? Well, not exactly;

‘Halloa!’ said Fledgeby, falling back, with a wink. ‘You mean mischief, Jerusalem!’

The old man raised his eyes inquiringly.

‘Yes you do,’ said Fledgeby. ‘Oh, you sinner! Oh, you dodger! What! You’re going to act upon that bill of sale at Lammle’s, are you? Nothing will turn you, won’t it? You won’t be put off for another single minute, won’t you?’

Ordered to immediate action by the master’s tone and look, the old man took up his hat from the little counter where it lay.

‘You have been told that he might pull through it, if you didn’t go in to win, Wide-Awake; have you?’ said Fledgeby. ‘And it’s not your game that he should pull through it; ain’t it? You having got security, and there being enough to pay you? Oh, you Jew!’

‘It seems to me,’ said Mrs Lammle, ‘that you have had no money at all, ever since we have been married.’

‘What seems to you,’ said Mr Lammle, ‘to have been the case, may possibly have been the case. It doesn’t matter.’

Was it the speciality of Mr and Mrs Lammle, or does it ever obtain with other loving couples? In these matrimonial dialogues they never addressed each other, but always some invisible presence that appeared to take a station about midway between them. Perhaps the skeleton in the cupboard comes out to be talked to, on such domestic occasions?

‘I have never seen any money in the house,’ said Mrs Lammle to the skeleton, ‘except my own annuity. That I swear.’

‘You needn’t take the trouble of swearing,’ said Mr Lammle to the skeleton; ‘once more, it doesn’t matter. You never turned your annuity to so good an account.’

During this breakfast talk we learn that the Lammles are about to "smash" as Mr. Lammle puts it. I can't remember how long these two have been married, but I don't know how they got this far without "smashing" a long time ago. How two people with no money manage to put food on the table is beyond me. And they also have a servant, how do they pay for a servant? We now find that Mr. Lammle has given a Jew a bill of sale on the furniture, and the Jew would have collected the furniture long ago if it hadn't been for Fledgeby. I'm assuming that the person really behind this bill of sale is Fledgeby in the first place, so what is he doing? He must have known their financial situation so why did he give them the money?

This chapter ended an idea I've had since we met the Lammles. And it's all because of you all that I thought this way at all. I've read the book a few times before and never considered Mr. Lammle was beating his wife until some of you mentioned it and then I thought you seemed right, no wonder she seemed to be afraid of him, but Dickens ends that idea with this;

"As Lammle, standing gathering up the skirts of his dressing-gown with his back to the fire, said this, looking down at his wife, she turned pale and looked down at the ground. With a sense of disloyalty upon her, and perhaps with a sense of personal danger—for she was afraid of him—even afraid of his hand and afraid of his foot, though he had never done her violence—she hastened to put herself right in his eyes."

So, if he has never done her physical harm why is she so afraid of him? Can she see that he would harm her if she pushed him too far? Now they discuss their future, how they can save themselves from being poor and homeless that is, and come up with a plan.

‘It is natural, Alfred,’ she said, looking up with some timidity into his face, ‘to think in such an emergency of the richest people we know, and the simplest.’

‘Just so, Sophronia.’

‘The Boffins.’

‘Just so, Sophronia.’

‘Is there nothing to be done with them?’

‘What is there to be done with them, Sophronia?’

She cast about in her thoughts again, and he kept his eye upon her as before.

‘Of course I have repeatedly thought of the Boffins, Sophronia,’ he resumed, after a fruitless silence; ‘but I have seen my way to nothing. They are well guarded. That infernal Secretary stands between them and—people of merit.’

‘If he could be got rid of?’ said she, brightening a little, after more casting about."

Their plan is to get rid of the secretary by turning Mr. Boffin against him. Mrs. Lammle is going to go to the Boffins telling them she cannot be silent on the actions of Rokesmith, believing that if they tell Mr. Boffin of Rokesmith's interest in Bella, and that he had made an offer to her, Mr. Boffin would be sure to dismiss him;

‘‘Suppose I so repeated it to Mr Boffin, as to insinuate that my sensitive delicacy and honour—’

‘Very good words, Sophronia.’

‘—As to insinuate that our sensitive delicacy and honour,’ she resumed, with a bitter stress upon the phrase, ‘would not allow us to be silent parties to so mercenary and designing a speculation on the Secretary’s part, and so gross a breach of faith towards his confiding employer. Suppose I had imparted my virtuous uneasiness to my excellent husband, and he had said, in his integrity, “Sophronia, you must immediately disclose this to Mr Boffin.”’

‘Once more, Sophronia,’ observed Lammle, changing the leg on which he stood, ‘I rather like that.’

At this time Fledgeby shows up at the door and Alfred leaves the room leaving his wife to deal with Fledgeby on her own. She tells Fledgeby that Alfred isn't there, that being so worried about their finances he left the house early. I'm wondering if she is attempting to get Fledgeby believe that Alfred is out trying to find some sort of employment. I can't quite picture Lammle doing any "real work". She asks Fledgeby if he can once again use his influence over Riah giving them more time to pay the bill,

‘Oh!’ said Fledgeby. ‘Then you think, Mrs Lammle, that if Lammle got time, he wouldn’t burst up?—To use an expression,’ Mr Fledgeby apologetically explained, ‘which is adopted in the Money Market.’

‘Indeed yes. Truly, truly, yes!’

‘That makes all the difference,’ said Fledgeby. ‘I’ll make a point of seeing Riah at once."

And now Fledgeby is off to see Riah and ask him to give the Lammles more time. Right? Well, not exactly;

‘Halloa!’ said Fledgeby, falling back, with a wink. ‘You mean mischief, Jerusalem!’

The old man raised his eyes inquiringly.

‘Yes you do,’ said Fledgeby. ‘Oh, you sinner! Oh, you dodger! What! You’re going to act upon that bill of sale at Lammle’s, are you? Nothing will turn you, won’t it? You won’t be put off for another single minute, won’t you?’

Ordered to immediate action by the master’s tone and look, the old man took up his hat from the little counter where it lay.

‘You have been told that he might pull through it, if you didn’t go in to win, Wide-Awake; have you?’ said Fledgeby. ‘And it’s not your game that he should pull through it; ain’t it? You having got security, and there being enough to pay you? Oh, you Jew!’

Chapter 13 is titled "Give a Dog a Bad Name, And Hang Him, this chapter with the rather unusual name finds us still with Fledgeby in the counting house waiting for Mr. Riah's return. Just as he is about to close the door, Jenny Wren enters. Jenny tells him that she is there to buy two shillings’ worth of waste. She asks him if he could let her have it instead of her having to wait, but he tells her he has nothing to do with the business. Hearing that she asks why then does Riah call him master?

‘One of his dodges,’ said Mr Fledgeby, with a cool and contemptuous shrug. ‘He’s made of dodges. He said to me, “Come up to the top of the house, sir, and I’ll show you a handsome girl. But I shall call you the master.” So I went up to the top of the house and he showed me the handsome girl (very well worth looking at she was), and I was called the master. I don’t know why. I dare say he don’t. He loves a dodge for its own sake; being,’ added Mr Fledgeby, after casting about for an expressive phrase, ‘the dodgerest of all the dodgers.’

‘Oh my head!’ cried the dolls’ dressmaker, holding it with both her hands, as if it were cracking. ‘You can’t mean what you say.’

Jenny is shocked to hear this about her good friend and becomes very quiet when another person enters the room. A "dried face of a mild little elderly gentleman", it is Mr. Twemlow. Fledgby tells him he is there on behalf of the Lammles; saying that when he was appealed to that morning by Mrs. Lammle, he had to come and try to pacify the creditor Mr. Riah. But he tells him as soon as he told Mr. Riah about the Lammles and their problem, Riah left the house saying he would be back directly.

Twemlow then related the reason for his visit is that he had had a deceased friend, a married civil officer with a family, who had wanted money for change of place on change of post, or something like that, and he had given his name, and now he is expected to repay what he never had.

Soon after this poor Mr. Riah returns to this;

‘I really thought,’ repeated Fledgeby slowly, ‘that you were lost, Mr Riah. Why, now I look at you—but no, you can’t have done it; no, you can’t have done it!’

Hat in hand, the old man lifted his head, and looked distressfully at Fledgeby as seeking to know what new moral burden he was to bear.

‘You can’t have rushed out to get the start of everybody else, and put in that bill of sale at Lammle’s?’ said Fledgeby. ‘Say you haven’t, Mr Riah.’

‘Sir, I have,’ replied the old man in a low voice.

‘Oh my eye!’ cried Fledgeby. ‘Tut, tut, tut! Dear, dear, dear! Well! I knew you were a hard customer, Mr Riah, but I never thought you were as hard as that.’

‘Sir,’ said the old man, with great uneasiness, ‘I do as I am directed. I am not the principal here. I am but the agent of a superior, and I have no choice, no power.’

And now Fledgeby moves on to Mr. Twemlow:

‘Mr Twemlow is no connexion of yours, Mr Riah,’ said Fledgeby; ‘you can’t want to be even with him for having through life gone in for a gentleman and hung on to his Family. If Mr Twemlow has a contempt for business, what can it matter to you?’

‘But pardon me,’ interposed the gentle victim, ‘I have not. I should consider it presumption.’

‘There, Mr Riah!’ said Fledgeby, ‘isn’t that handsomely said? Come! Make terms with me for Mr Twemlow.’

The old man looked again for any sign of permission to spare the poor little gentleman. No. Mr Fledgeby meant him to be racked.

‘I am very sorry, Mr Twemlow,’ said Riah. ‘I have my instructions. I am invested with no authority for diverging from them. The money must be paid.’

Why does Mr. Riah put up with this? I can't remember. The chapter ends with this:

‘He looked on for a time, as the Jew filled her little basket with such scraps as she was used to buy; but, his merry vein coming on again, he was obliged to turn round to the window once more, and lean his arms on the blind.

‘There, my Cinderella dear,’ said the old man in a whisper, and with a worn-out look, ‘the basket’s full now. Bless you! And get you gone!’

‘Don’t call me your Cinderella dear,’ returned Miss Wren. ‘O you cruel godmother!’

She shook that emphatic little forefinger of hers in his face at parting, as earnestly and reproachfully as she had ever shaken it at her grim old child at home.

‘You are not the godmother at all!’ said she. ‘You are the Wolf in the Forest, the wicked Wolf! And if ever my dear Lizzie is sold and betrayed, I shall know who sold and betrayed her!’

‘One of his dodges,’ said Mr Fledgeby, with a cool and contemptuous shrug. ‘He’s made of dodges. He said to me, “Come up to the top of the house, sir, and I’ll show you a handsome girl. But I shall call you the master.” So I went up to the top of the house and he showed me the handsome girl (very well worth looking at she was), and I was called the master. I don’t know why. I dare say he don’t. He loves a dodge for its own sake; being,’ added Mr Fledgeby, after casting about for an expressive phrase, ‘the dodgerest of all the dodgers.’

‘Oh my head!’ cried the dolls’ dressmaker, holding it with both her hands, as if it were cracking. ‘You can’t mean what you say.’

Jenny is shocked to hear this about her good friend and becomes very quiet when another person enters the room. A "dried face of a mild little elderly gentleman", it is Mr. Twemlow. Fledgby tells him he is there on behalf of the Lammles; saying that when he was appealed to that morning by Mrs. Lammle, he had to come and try to pacify the creditor Mr. Riah. But he tells him as soon as he told Mr. Riah about the Lammles and their problem, Riah left the house saying he would be back directly.

Twemlow then related the reason for his visit is that he had had a deceased friend, a married civil officer with a family, who had wanted money for change of place on change of post, or something like that, and he had given his name, and now he is expected to repay what he never had.

Soon after this poor Mr. Riah returns to this;

‘I really thought,’ repeated Fledgeby slowly, ‘that you were lost, Mr Riah. Why, now I look at you—but no, you can’t have done it; no, you can’t have done it!’

Hat in hand, the old man lifted his head, and looked distressfully at Fledgeby as seeking to know what new moral burden he was to bear.

‘You can’t have rushed out to get the start of everybody else, and put in that bill of sale at Lammle’s?’ said Fledgeby. ‘Say you haven’t, Mr Riah.’

‘Sir, I have,’ replied the old man in a low voice.

‘Oh my eye!’ cried Fledgeby. ‘Tut, tut, tut! Dear, dear, dear! Well! I knew you were a hard customer, Mr Riah, but I never thought you were as hard as that.’

‘Sir,’ said the old man, with great uneasiness, ‘I do as I am directed. I am not the principal here. I am but the agent of a superior, and I have no choice, no power.’

And now Fledgeby moves on to Mr. Twemlow:

‘Mr Twemlow is no connexion of yours, Mr Riah,’ said Fledgeby; ‘you can’t want to be even with him for having through life gone in for a gentleman and hung on to his Family. If Mr Twemlow has a contempt for business, what can it matter to you?’

‘But pardon me,’ interposed the gentle victim, ‘I have not. I should consider it presumption.’

‘There, Mr Riah!’ said Fledgeby, ‘isn’t that handsomely said? Come! Make terms with me for Mr Twemlow.’

The old man looked again for any sign of permission to spare the poor little gentleman. No. Mr Fledgeby meant him to be racked.

‘I am very sorry, Mr Twemlow,’ said Riah. ‘I have my instructions. I am invested with no authority for diverging from them. The money must be paid.’

Why does Mr. Riah put up with this? I can't remember. The chapter ends with this:

‘He looked on for a time, as the Jew filled her little basket with such scraps as she was used to buy; but, his merry vein coming on again, he was obliged to turn round to the window once more, and lean his arms on the blind.

‘There, my Cinderella dear,’ said the old man in a whisper, and with a worn-out look, ‘the basket’s full now. Bless you! And get you gone!’

‘Don’t call me your Cinderella dear,’ returned Miss Wren. ‘O you cruel godmother!’

She shook that emphatic little forefinger of hers in his face at parting, as earnestly and reproachfully as she had ever shaken it at her grim old child at home.

‘You are not the godmother at all!’ said she. ‘You are the Wolf in the Forest, the wicked Wolf! And if ever my dear Lizzie is sold and betrayed, I shall know who sold and betrayed her!’

Our last chapter for this installment is titled, "Mr. Wegg Prepares A Grindstone For Mr. Boffin's Nose. We begin with Mr. Venus now being a regular visitor at the Bowery in the evenings for the readings by Wegg. Having another listener seemed to heighten Mr. Boffin's enjoyment for some reason. During one of these evenings Mr. Venus passes Mr. Boffin a note asking him to stop at the shop the next evening, and the very next evening Mr. Boffin arrives. Mr. Venus tells him the reason he has asked to see him;

‘Mr Boffin, if I confess to you that I fell into a proposal of which you were the subject, and of which you oughtn’t to have been the subject, you will allow me to mention, and will please take into favourable consideration, that I was in a crushed state of mind at the time.’.......

.....‘That proposal, sir, was a conspiring breach of your confidence, to such an extent, that I ought at once to have made it known to you. But I didn’t, Mr Boffin, and I fell into it.’

‘Not that I was ever hearty in it, sir,’ the penitent anatomist went on, ‘or that I ever viewed myself with anything but reproach for having turned out of the paths of science into the paths of—’ he was going to say ‘villany,’ but, unwilling to press too hard upon himself, substituted with great emphasis—‘Weggery.’.....

.....‘And now, sir,’ said Venus, ‘having prepared your mind in the rough, I will articulate the details.’.......

‘Now, sir,’ said Venus, finishing off; ‘you best know what was in that Dutch bottle, and why you dug it up, and took it away. I don’t pretend to know anything more about it than I saw. All I know is this: I am proud of my calling after all (though it has been attended by one dreadful drawback which has told upon my heart, and almost equally upon my skeleton), and I mean to live by my calling. Putting the same meaning into other words, I do not mean to turn a single dishonest penny by this affair. As the best amends I can make you for having ever gone into it, I make known to you, as a warning, what Wegg has found out. My opinion is, that Wegg is not to be silenced at a modest price, and I build that opinion on his beginning to dispose of your property the moment he knew his power. Whether it’s worth your while to silence him at any price, you will decide for yourself, and take your measures accordingly. As far as I am concerned, I have no price. If I am ever called upon for the truth, I tell it, but I want to do no more than I have now done and ended.’

As they discuss this they hear Wegg coming and Mr. Boffin hides behind an alligator in the corner. I wonder if there is a good business in selling alligators, dead ones that is. And now Mr. Boffin can hear the discussion between the two, hear are a few examples of it;

‘‘Then he must have a hint of it,’ said Wegg, ‘and a strong one that’ll jog his terrors a bit. Give him an inch, and he’ll take an ell. Let him alone this time, and what’ll he do with our property next? I tell you what, Mr Venus; it comes to this; I must be overbearing with Boffin, or I shall fly into several pieces. I can’t contain myself when I look at him. Every time I see him putting his hand in his pocket, I see him putting it into my pocket. Every time I hear him jingling his money, I hear him taking liberties with my money. Flesh and blood can’t bear it. No,’ said Mr Wegg, greatly exasperated, ‘and I’ll go further. A wooden leg can’t bear it!’

When Wegg is gone Mr. Boffin asks Venus to make a show of remaining in it until he has time to turn himself around. When Venus asks him how long it will take him to do this turning himself around and Mr. Boffin says;

‘I am sure I don’t know what to do,’ said Mr Boffin. ‘If I ask advice of any one else, it’s only letting in another person to be bought out, and then I shall be ruined that way, and might as well have given up the property and gone slap to the workhouse. If I was to take advice of my young man, Rokesmith, I should have to buy him out. Sooner or later, of course, he’d drop down upon me, like Wegg. I was brought into the world to be dropped down upon, it appears to me.’

I find it interesting that Venus won't give the will to Mr. Boffin, neither will he burn it, but plans on giving it back to Wegg telling him he would have nothing more to do with it and Wegg must act as he chose, and take the consequences. It seems giving the will back to Wegg will not help Mr. Boffin at all. Mr. Boffin asks Venus if he is willing to pretend to still be in with Wegg, at least until the mounds are clear but Venus says that would be too long and we have this:

‘Not if I was to show you reason now?’ demanded Mr Boffin; ‘not if I was to show you good and sufficient reason?’

If by good and sufficient reason Mr Boffin meant honest and unimpeachable reason, that might weigh with Mr Venus against his personal wishes and convenience. But he must add that he saw no opening to the possibility of such reason being shown him.

‘Come and see me, Venus,’ said Mr Boffin, ‘at my house.’

‘Is the reason there, sir?’ asked Mr Venus, with an incredulous smile and blink.

‘It may be, or may not be,’ said Mr Boffin, ‘just as you view it. ’

What do you suppose the good and sufficient reason may be? There certainly a lot of mystery to our book. And now Mr. Boffin is on his way home wondering if Venus really just wanted to get ahead of Wegg, So he doesn't trust Venus, I'm not sure in his role of miser now he trusts anyone. The chapter ends with a carriage pulls up to him, inside is Mrs. Lammle and she asks Mr. Boffin if she may talk to him, I'll end with this:

‘It was Alfred who sent me to you, Mr Boffin. Alfred said, “Don’t come back, Sophronia, until you have seen Mr Boffin, and told him all. Whatever he may think of it, he ought certainly to know it.” Would you mind coming into the carriage?’

Mr Boffin answered, ‘Not at all,’ and took his seat at Mrs Lammle’s side.

‘Drive slowly anywhere,’ Mrs Lammle called to her coachman, ‘and don’t let the carriage rattle.’

‘It must be more dropping down, I think,’ said Mr Boffin to himself. ‘What next?’

‘Mr Boffin, if I confess to you that I fell into a proposal of which you were the subject, and of which you oughtn’t to have been the subject, you will allow me to mention, and will please take into favourable consideration, that I was in a crushed state of mind at the time.’.......

.....‘That proposal, sir, was a conspiring breach of your confidence, to such an extent, that I ought at once to have made it known to you. But I didn’t, Mr Boffin, and I fell into it.’

‘Not that I was ever hearty in it, sir,’ the penitent anatomist went on, ‘or that I ever viewed myself with anything but reproach for having turned out of the paths of science into the paths of—’ he was going to say ‘villany,’ but, unwilling to press too hard upon himself, substituted with great emphasis—‘Weggery.’.....

.....‘And now, sir,’ said Venus, ‘having prepared your mind in the rough, I will articulate the details.’.......

‘Now, sir,’ said Venus, finishing off; ‘you best know what was in that Dutch bottle, and why you dug it up, and took it away. I don’t pretend to know anything more about it than I saw. All I know is this: I am proud of my calling after all (though it has been attended by one dreadful drawback which has told upon my heart, and almost equally upon my skeleton), and I mean to live by my calling. Putting the same meaning into other words, I do not mean to turn a single dishonest penny by this affair. As the best amends I can make you for having ever gone into it, I make known to you, as a warning, what Wegg has found out. My opinion is, that Wegg is not to be silenced at a modest price, and I build that opinion on his beginning to dispose of your property the moment he knew his power. Whether it’s worth your while to silence him at any price, you will decide for yourself, and take your measures accordingly. As far as I am concerned, I have no price. If I am ever called upon for the truth, I tell it, but I want to do no more than I have now done and ended.’

As they discuss this they hear Wegg coming and Mr. Boffin hides behind an alligator in the corner. I wonder if there is a good business in selling alligators, dead ones that is. And now Mr. Boffin can hear the discussion between the two, hear are a few examples of it;

‘‘Then he must have a hint of it,’ said Wegg, ‘and a strong one that’ll jog his terrors a bit. Give him an inch, and he’ll take an ell. Let him alone this time, and what’ll he do with our property next? I tell you what, Mr Venus; it comes to this; I must be overbearing with Boffin, or I shall fly into several pieces. I can’t contain myself when I look at him. Every time I see him putting his hand in his pocket, I see him putting it into my pocket. Every time I hear him jingling his money, I hear him taking liberties with my money. Flesh and blood can’t bear it. No,’ said Mr Wegg, greatly exasperated, ‘and I’ll go further. A wooden leg can’t bear it!’

When Wegg is gone Mr. Boffin asks Venus to make a show of remaining in it until he has time to turn himself around. When Venus asks him how long it will take him to do this turning himself around and Mr. Boffin says;

‘I am sure I don’t know what to do,’ said Mr Boffin. ‘If I ask advice of any one else, it’s only letting in another person to be bought out, and then I shall be ruined that way, and might as well have given up the property and gone slap to the workhouse. If I was to take advice of my young man, Rokesmith, I should have to buy him out. Sooner or later, of course, he’d drop down upon me, like Wegg. I was brought into the world to be dropped down upon, it appears to me.’

I find it interesting that Venus won't give the will to Mr. Boffin, neither will he burn it, but plans on giving it back to Wegg telling him he would have nothing more to do with it and Wegg must act as he chose, and take the consequences. It seems giving the will back to Wegg will not help Mr. Boffin at all. Mr. Boffin asks Venus if he is willing to pretend to still be in with Wegg, at least until the mounds are clear but Venus says that would be too long and we have this:

‘Not if I was to show you reason now?’ demanded Mr Boffin; ‘not if I was to show you good and sufficient reason?’

If by good and sufficient reason Mr Boffin meant honest and unimpeachable reason, that might weigh with Mr Venus against his personal wishes and convenience. But he must add that he saw no opening to the possibility of such reason being shown him.

‘Come and see me, Venus,’ said Mr Boffin, ‘at my house.’

‘Is the reason there, sir?’ asked Mr Venus, with an incredulous smile and blink.

‘It may be, or may not be,’ said Mr Boffin, ‘just as you view it. ’

What do you suppose the good and sufficient reason may be? There certainly a lot of mystery to our book. And now Mr. Boffin is on his way home wondering if Venus really just wanted to get ahead of Wegg, So he doesn't trust Venus, I'm not sure in his role of miser now he trusts anyone. The chapter ends with a carriage pulls up to him, inside is Mrs. Lammle and she asks Mr. Boffin if she may talk to him, I'll end with this:

‘It was Alfred who sent me to you, Mr Boffin. Alfred said, “Don’t come back, Sophronia, until you have seen Mr Boffin, and told him all. Whatever he may think of it, he ought certainly to know it.” Would you mind coming into the carriage?’

Mr Boffin answered, ‘Not at all,’ and took his seat at Mrs Lammle’s side.

‘Drive slowly anywhere,’ Mrs Lammle called to her coachman, ‘and don’t let the carriage rattle.’

‘It must be more dropping down, I think,’ said Mr Boffin to himself. ‘What next?’

Kim wrote: "Dear Curiosities,

We have made our way to Chapter 11 of Book 3 after following Eugene up one lane and down another until we are worn out. At least our schoolmaster, Bradley Headstone is quite worn..."

Bradley Headstone. He is one scary piece of work. To me, OMF presents us with more interesting and disturbing character studies than any other novel. We have, for starters, the curious eccentricities of Boffin and Jenny Wren, the sinister Fledgeby and the twisted relationship of the Lammles. None, however, at least to me, come close to the striking character of Bradley Headstone.

Did R L Stevenson find his inspiration for Jeckyl and Hyde here? Concerning Headstone, Dickens writes "Tied up all day with his disciplined show upon him ... he broke loose at night like an ill-tamed wild animal." Headstone is a stalker and perverse. His interest and self-delusions of love with Lizzie are balanced by the hate that he holds for Eugene Wrayburn.

Reading this chapter we see Dickens join the characters of Headstone and Riderhood. This cannot be good. In terms of foreshadowing, however, this is a match made in literary heaven. As readers we know something evil will stalk the next few chapters. The fact that Riderhood holds the position of Deputy Lock-Keeper and thus retains his link with the Thames heightens further the feeling of discomfort I have. The Thames has not been kind to many characters so far in our reading. Will the Thames continued presence have ominous overtones?

We have made our way to Chapter 11 of Book 3 after following Eugene up one lane and down another until we are worn out. At least our schoolmaster, Bradley Headstone is quite worn..."

Bradley Headstone. He is one scary piece of work. To me, OMF presents us with more interesting and disturbing character studies than any other novel. We have, for starters, the curious eccentricities of Boffin and Jenny Wren, the sinister Fledgeby and the twisted relationship of the Lammles. None, however, at least to me, come close to the striking character of Bradley Headstone.

Did R L Stevenson find his inspiration for Jeckyl and Hyde here? Concerning Headstone, Dickens writes "Tied up all day with his disciplined show upon him ... he broke loose at night like an ill-tamed wild animal." Headstone is a stalker and perverse. His interest and self-delusions of love with Lizzie are balanced by the hate that he holds for Eugene Wrayburn.

Reading this chapter we see Dickens join the characters of Headstone and Riderhood. This cannot be good. In terms of foreshadowing, however, this is a match made in literary heaven. As readers we know something evil will stalk the next few chapters. The fact that Riderhood holds the position of Deputy Lock-Keeper and thus retains his link with the Thames heightens further the feeling of discomfort I have. The Thames has not been kind to many characters so far in our reading. Will the Thames continued presence have ominous overtones?

Kim wrote: "Chapter 12 is titled "Meaning Mischief" and we have left Bradley and Riderhood with their plots to drop in on the Lammle's, who are at this moment having breakfast:

‘It seems to me,’ said Mrs Lamm..."

Kim

You have found the essential reference that documents the fact that Lammle has not, as yet, physically assaulted Mrs. Lammle.

The sinister nature of Lammle must rest in his potential of evil. He is a man whose violence is constantly brewing, but evidently not as yet unleashed. We do know that both Lammles are schemers and cheats. We have witnessed some modicum of kindness when Mrs. Lammle has Twemlow warn the Veneerings away from the Lammles. They are a nasty pair of people who are dangerous to both society and to each other.

Structurally, it is interesting to note that Dickens has paired chapters 11-12 (XLIV-XLV) These chapters further develop the plot of how two pairs of evil characters - Headstone and Riderhood and The Lammles have been positioned by Dickens to further disperse their disruptive influences in the novel.

‘It seems to me,’ said Mrs Lamm..."

Kim

You have found the essential reference that documents the fact that Lammle has not, as yet, physically assaulted Mrs. Lammle.

The sinister nature of Lammle must rest in his potential of evil. He is a man whose violence is constantly brewing, but evidently not as yet unleashed. We do know that both Lammles are schemers and cheats. We have witnessed some modicum of kindness when Mrs. Lammle has Twemlow warn the Veneerings away from the Lammles. They are a nasty pair of people who are dangerous to both society and to each other.

Structurally, it is interesting to note that Dickens has paired chapters 11-12 (XLIV-XLV) These chapters further develop the plot of how two pairs of evil characters - Headstone and Riderhood and The Lammles have been positioned by Dickens to further disperse their disruptive influences in the novel.

The weather in New Jersey, USA, turned noticeably cooler this weekend. Cloudy, gray, and rainy. So I should get to Chapter 14 easy peazy with a cup of tea or two.

The weather in New Jersey, USA, turned noticeably cooler this weekend. Cloudy, gray, and rainy. So I should get to Chapter 14 easy peazy with a cup of tea or two.

Kim wrote: "Dear Curiosities,

Kim wrote: "Dear Curiosities,We have made our way to Chapter 11 of Book 3 after following Eugene up one lane and down another until we are worn out. At least our schoolmaster, Bradley Headstone is quite worn..."

Do you suppose he really would or will actually murder Eugene if he finds him, or is it his hatred talking, thinking to himself that, yes, he will kill him, but it is just an idea, he wouldn't really go through with it, or does he intend to out and out murder him?

Oh, goodness... I absolutely believe this man has it in him to murder Wrayburn. I wondered then, in that chapter which described everything about Bradley Headstone being decent, what was the need for the repetition of that word...It's because everything that Bradley Headstone is known for, which is being decent, has been thrown to the wind since his display of rage in the cemetery with Lizzie Hexam, where he was attempting to pronounce his love for her. What I find most interesting about Lizzie's suitors is that they are both on opposite ends of the spectrum in every way one can name...The only commonality between the two being, Lizzie Hexam.

We have Bradley Headstone, who raised himself up from nothing to be a decent man with his decent clothes, forcing himself into the position of decent headmaster. He is threateningly obsessed with Lizzie, thinking to himself that his being a decent man is enough to pressure the hand of this woman in marriage. Headstone, is determined to have her, and it appears at no cost.

Then, there's Eugene Wrayburn who comes from means, never having to lift a finger in his life. He has a profession that he does not actively pursue (if even that), apathetic about life- a rather bored individual, a rather very boring character. A man, emotionally, neither here nor there as it first appears; but he's consumed with thoughts of Lizzie not able to make heads or tails of them, not realizing he's been the latest victim of cupid's arrows. His approach to Lizzie, is comparable to his approach with life...Passive. Wrayburn needs a jolt of some type to realize he is in fact, in love with Lizzie Hexam.

Kim wrote: "Chapter 13 is titled "Give a Dog a Bad Name, And Hang Him, this chapter with the rather unusual name finds us still with Fledgeby in the counting house waiting for Mr. Riah's return. Just as he is ..."

Kim wrote: "Chapter 13 is titled "Give a Dog a Bad Name, And Hang Him, this chapter with the rather unusual name finds us still with Fledgeby in the counting house waiting for Mr. Riah's return. Just as he is ..."Why does Mr. Riah put up with this? I can't remember.

I wondered this as well, Kim. I may have missed it, but if not; considering who Fledgby is, maybe Riah is paying on some debt owed to Fledgeby by working for him?

Ami wrote: "Kim wrote: "Dear Curiosities,

We have made our way to Chapter 11 of Book 3 after following Eugene up one lane and down another until we are worn out. At least our schoolmaster, Bradley Headstone i..."

Hi Ami

Yes. I am also fascinated by diction and the denotation and connotation of words. Decent .For such a short word there is much ambiguity.

We have made our way to Chapter 11 of Book 3 after following Eugene up one lane and down another until we are worn out. At least our schoolmaster, Bradley Headstone i..."

Hi Ami

Yes. I am also fascinated by diction and the denotation and connotation of words. Decent .For such a short word there is much ambiguity.

Peter wrote: "Ami wrote: "Kim wrote: "Dear Curiosities,

Peter wrote: "Ami wrote: "Kim wrote: "Dear Curiosities,We have made our way to Chapter 11 of Book 3 after following Eugene up one lane and down another until we are worn out. At least our schoolmaster, Bradley..."

I also thought, in this novel full of characters in disguise either literally or figuratively, if the "connotation of words" (repetition) is yet another manner in which Dickens veils his characters...Considering, nothing is as it seems, doesn't this seem possible?

P.S. Hi Peter. :)

Does anyone have a handle on how old Riderhood is -- an approximate perhaps?

Does anyone have a handle on how old Riderhood is -- an approximate perhaps?I can't really come to terms whether he is young, middle aged, or old. Thanks.

Ami wrote: "Peter wrote: "Ami wrote: "Kim wrote: "Dear Curiosities,

We have made our way to Chapter 11 of Book 3 after following Eugene up one lane and down another until we are worn out. At least our schoolm..."

Hello back Ami

Yes. To me, OMF wins the prize for the Dickens novel with the most use of disguise, surprise character revelations, binary characters, parallel events, duel and contrasting settings and other stylistic devices. It's enough to make one dizzy.

We have made our way to Chapter 11 of Book 3 after following Eugene up one lane and down another until we are worn out. At least our schoolm..."

Hello back Ami

Yes. To me, OMF wins the prize for the Dickens novel with the most use of disguise, surprise character revelations, binary characters, parallel events, duel and contrasting settings and other stylistic devices. It's enough to make one dizzy.

John wrote: "Does anyone have a handle on how old Riderhood is -- an approximate perhaps?

I can't really come to terms whether he is young, middle aged, or old. Thanks."

John

I cannot recall our being told Riderhood's exact age by Dickens. We know he has a daughter who is old enough to be the proprietor of a sailors' B&B and run a ratty pawn store. Since she was raised on the rough side of town this could make her in the early to mid twenties. Let's say Riderhood became a father in his late teens to mid twenties I'd guess he was around 40 - 45 or thereabouts in the novel.

I can't really come to terms whether he is young, middle aged, or old. Thanks."

John

I cannot recall our being told Riderhood's exact age by Dickens. We know he has a daughter who is old enough to be the proprietor of a sailors' B&B and run a ratty pawn store. Since she was raised on the rough side of town this could make her in the early to mid twenties. Let's say Riderhood became a father in his late teens to mid twenties I'd guess he was around 40 - 45 or thereabouts in the novel.

Peter wrote: "John wrote: "Does anyone have a handle on how old Riderhood is -- an approximate perhaps?

Peter wrote: "John wrote: "Does anyone have a handle on how old Riderhood is -- an approximate perhaps?I can't really come to terms whether he is young, middle aged, or old. Thanks."

John

I cannot recall our..."

Thank you. These days I think of 40 as "young."

Is Bradley Headstone a potential murderer?

Like most of you here, I would say that he definitely has it in himself to murder Eugene. As Ami worked out, Bradley had a very hard time to achieve a decent and respectable position in life, and he did it through hard work and through suppressing his impulsive and passionate nature. Meeting Lizzie, however, made it impossible for him to continue suppressing his passions, and we can probably say that something has broken inside him. Now, I would not go so far as Peter and say that he is actually a pervert because I don't think his stalking Lizzie gratifies any sexual desire within him but he has definitely become unhinged. Seeing that he will probably never be united with Lizzie, he is bent on getting the second best thing, to him - i.e. destroying Eugene, who not only took Lizzie away from him, as he surmises, but who also showed him that he despises him and that all his effort and ambitions went to nought when it comes to holding his head up among people from Eugene's walk of life. The destructive edge of his "love" also becomes clear when Bradley shows no hesitation at all to join forces with Riderhood, the man who actually gave a bad name to the father of the woman Bradley professes to love. Were his love less egocentric, he would shy away from Riderhood, but as Bradley is now simply bent on destruction, this is all one to him.

Mr Lammle and physical violence. I found it very interesting that the text explicitly states that Lammle has never, as yet, beaten his wife. This shows that the danger of his doing so one day must actually have occurred to Mrs Lammle as a future menace. Maybe Sophronia thinks that if her husband finds himself at the end of his tether, he will not think twice about using violence - all the more so, as his wife was the cause of their first plan going awry.

Riah's passivity. I could not help feeling very dismayed by what happened in the "Give a Dog a Bad Name" chapter. Is there not the point in a person's life when, by doing nothing, a person makes himself part of the wrong that is inflicted? In the present situation, Mr Riah could easily have "misread" Fledgeby's supplications and granted Twemlow some quarter. Maybe, this would have forced Fledgeby to drop his mask and show himself the evil man he is. The way Riah acted, he even helped Fledgeby worm himself deeper into the poor debtor's confidence. I am also worried by Jenny's last words to Riah. Are we to assume that there is trouble ahead for Lizzie then?

Like most of you here, I would say that he definitely has it in himself to murder Eugene. As Ami worked out, Bradley had a very hard time to achieve a decent and respectable position in life, and he did it through hard work and through suppressing his impulsive and passionate nature. Meeting Lizzie, however, made it impossible for him to continue suppressing his passions, and we can probably say that something has broken inside him. Now, I would not go so far as Peter and say that he is actually a pervert because I don't think his stalking Lizzie gratifies any sexual desire within him but he has definitely become unhinged. Seeing that he will probably never be united with Lizzie, he is bent on getting the second best thing, to him - i.e. destroying Eugene, who not only took Lizzie away from him, as he surmises, but who also showed him that he despises him and that all his effort and ambitions went to nought when it comes to holding his head up among people from Eugene's walk of life. The destructive edge of his "love" also becomes clear when Bradley shows no hesitation at all to join forces with Riderhood, the man who actually gave a bad name to the father of the woman Bradley professes to love. Were his love less egocentric, he would shy away from Riderhood, but as Bradley is now simply bent on destruction, this is all one to him.

Mr Lammle and physical violence. I found it very interesting that the text explicitly states that Lammle has never, as yet, beaten his wife. This shows that the danger of his doing so one day must actually have occurred to Mrs Lammle as a future menace. Maybe Sophronia thinks that if her husband finds himself at the end of his tether, he will not think twice about using violence - all the more so, as his wife was the cause of their first plan going awry.

Riah's passivity. I could not help feeling very dismayed by what happened in the "Give a Dog a Bad Name" chapter. Is there not the point in a person's life when, by doing nothing, a person makes himself part of the wrong that is inflicted? In the present situation, Mr Riah could easily have "misread" Fledgeby's supplications and granted Twemlow some quarter. Maybe, this would have forced Fledgeby to drop his mask and show himself the evil man he is. The way Riah acted, he even helped Fledgeby worm himself deeper into the poor debtor's confidence. I am also worried by Jenny's last words to Riah. Are we to assume that there is trouble ahead for Lizzie then?

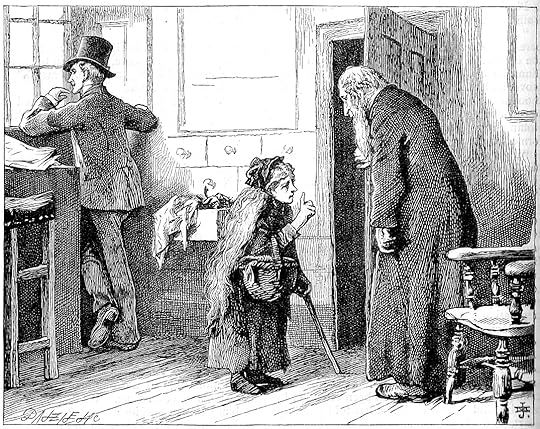

Mr. Fledgeby Departs on His Errand of Mercy

Book 3 Chapter 12

Marcus Stone

Commentary:

Stone's illustration for Book 3, "A Long Lane," Chapter 12, "Meaning Mischief," appeared in the June, 1865, installment. The scene is the Lammles' breakfast parlor where the couple have recently considered their prospects and have mutually agreed to use their knowledge of Rokesmith's proposal to Bella to manipulate Boffin to discharge the secretary and replace him with Alfred Lammle in order to advance their larger scheme of defrauding Boffin. Seeing Fascination Fledgeby arriving at their door, Lammle retreats, leaving his wife to deal with their inconvenient acquaintance.

When Sophronia Lammle reveals their temporary difficulty with a money-lender who is a mutual acquaintance, Fledgeby promises to be of assistance to the Lammles in intervening on their behalf with Riah of Pubsey & Co. In fact, in his true guise as the firm's owner, Fledgeby subsequently enjoins his employee to act on Lammle's note and move to confiscate the Lammles' furniture at their Sackville Street residence. Although the illustration does not in the least suggest Fledgeby's duplicity, Stone captures well Mrs. Lammle's feeling of discomfort at Fledgeby's kissing her hand to seal his promise of assistance. The passage which terminates in Fledgeby's chivalric gesture is this:

'Alfred, dear Mr. Fledgeby, discussed with me this very morning before he went out, some prospects he has, which might entirely change the aspect of his present troubles.'

'Really?' said Fledgeby.

'O yes!' Here Mrs. Lammle brought her handkerchief into play. 'And you know, dear Mr. Fledgeby — you who study the human heart, and study the world — what an affliction it would be to lose position and to lose credit, when ability to tide over a very short time might save all appearances.'

'Oh!' said Fledgeby. 'Then you think, Mrs. Lammle, that if Lammle got time, he wouldn't burst up? — To use an expression,' Mr. Fledgeby apologetically explained, 'which is adopted in the Money Market.'

'Indeed yes. Truly, truly, yes!'

'That makes all the difference,' said Fledgeby. 'I'll make a point of seeing Riah at once.'

'Blessings on you, dearest Mr. Fledgeby!'

'Not at all,' said Fledgeby. She gave him her hand. 'The hand,' said Mr Fledgeby, 'of a lovely and superior-minded female is ever the repayment of a —

'

'Noble action!' said Mrs. Lammle, extremely anxious to get rid of him.

'It wasn't what I was going to say,' returned Fledgeby, who never would, under any circumstances, accept a suggested expression, 'but you're very complimentary. May I imprint a — a one — upon it? Good morning!'

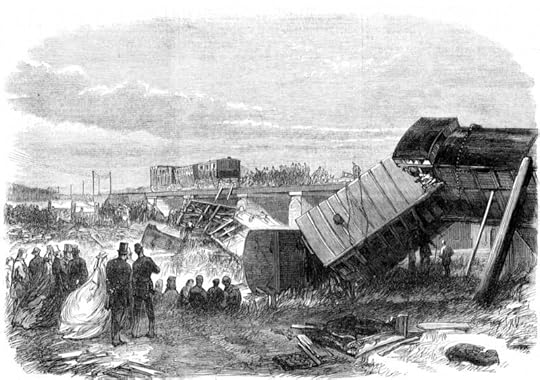

"She shook that emphatic little forefinger of hers in his face at parting."

Book 3 Chapter 13

James Mahoney

Household Edition 1875

Text Illustrated:

Fascination Fledgeby was in such a merry vein when the counting-house was cleared of him, that he had nothing for it but to go to the window, and lean his arms on the frame of the blind, and have his silent laugh out, with his back to his subordinate. When he turned round again with a composed countenance, his subordinate still stood in the same place, and the dolls' dressmaker sat behind the door with a look of horror.

"Halloa!" cried Mr. Fledgeby, "you're forgetting this young lady, Mr. Riah, and she has been waiting long enough too. Sell her her waste, please, and give her good measure if you can make up your mind to do the liberal thing for once."

He looked on for a time, as the Jew filled her little basket with such scraps as she was used to buy; but, his merry vein coming on again, he was obliged to turn round to the window once more, and lean his arms on the blind.

"There, my Cinderella dear," said the old man in a whisper, and with a worn-out look, "the basket's full now. Bless you! And get you gone!"

"Don't call me your Cinderella dear," returned Miss Wren. "O you cruel godmother!"

She shook that emphatic little forefinger of hers in his face at parting, as earnestly and reproachfully as she had ever shaken it at her grim old child at home.

"You are not the godmother at all!" said she. "You are the Wolf in the Forest, the wicked Wolf! And if ever my dear Lizzie is sold and betrayed, I shall know who sold and betrayed her!"

Commentary:

The Chapman and Hall woodcut for thirteenth chapter, "Give a Dog a Bad Name, and Hang Him," in the third book, "A Long Lane," has a much longer caption than that in the Harper and Brothers volume, published that same year in New York: "She shook that emphatic little forefinger of hers in his face at parting, as earnestly and reproachfully as she had ever shaken it at her grim old child at home". Otherwise, the wood-engraving depicting the Jenny's reproaching Riah for his hard-hearted treatment of Twemlow (in fact, his "superior's" uncompromising treatment of the debtor) is identical in both volumes, suggesting that the Dalziels produced two copies of each woodblock engraving from Mahoney's original line-drawings. This is yet another of those illustrations possessing a different caption in the Chapman and Hall and Harper and Brothers versions of the same book, so that, although the American publisher must have received a list of illustrations, the firm's editor chose occasionally to deviate from the given wording and did not give such a list at the beginning of the volume.

Ami wrote: "Kim wrote: "Why does Mr. Riah put up with this? I can't remember...."

Ami wrote: "Kim wrote: "Why does Mr. Riah put up with this? I can't remember...."It's something to do with feeling indebted to Fledgeby for keeping him employed when he took over his father's business. Can't remember the reference though :( And I agree with your reservations Tristram. Surely at some point the worm must turn? Riah clearly is way above all these dodgy business tactics.

"Mr. Wegg prepares a Grindstone for Mr. Boffin's Nose"

Book 3 Chapter 14

Marcus Stone

Commentary:

The setting is once again, as in "Mr. Venus Surrounded by the Trophies of His Art" (June 1864), the taxidermist's shop of the melancholy, rejected suitor Mr. Venus, where, with Boffin hiding behind the stuffed alligator, the moral artisan draws out Wegg about his feelings regarding Boffin as a result of the suppositous will that invalidates most of the Golden Dustman's claim to the Harmon estate:

'My time, sir,' returned Wegg, 'is yours. In the meanwhile let it be fully understood that I shall not neglect bringing the grindstone to bear, nor yet bringing Dusty Boffin's nose to it. His nose once brought to it, shall be held to it by these hands, Mr. Venus, till the sparks flies out in showers.'

As Wegg rants about Boffin's being made to pay for Wegg's silence regarding the second will, Boffin listens safely from his place of hiding, behind the young alligator. This time, however, in contrast to the former illustration, the artist's interest is not so much Venus's shop and its macabre contents as the two characters who discuss how they may transform the waste of the mounds into gold through blackmail. Venus is easily distinguished by his shock of ginger hair and leather apron, Wegg by his top hat and peg leg. The ubiquitous grinning skulls supplied by the illustrator suggest, as does Dickens's mention of the French gentleman (the articulated skeleton), suggest that there are eavesdroppers on this very private conversation.

Everything else, however, looks different because Stone has changed the orientation of the picture of Venus's shop; formerly, we regarded Venus's counter and fireplace from within, so that the window formed the backdrop. Now, the counter is to the right, and the fireplace is apparently behind the conspirators, so that the viewer has been given a different perspective. Similarly, the reader now regards the lovelorn taxidermist in a different light after his revelations to Boffin — and his refusal to be bribed to suppress or hand over the will. The unlit candle on the corner of the counter is faithful to Dickens's text, although the room is rather better lit. Moreover, Stone's placing the alligator on the floor does not seem plausible, since Venus instructs Boffin to draw in his legs:

The Golden Dustman seemed about to pursue these questions, when a stumping noise was heard outside, coming towards the door. 'Hush! here's Wegg!' said Venus. 'Get behind the young alligator in the corner, Mr. Boffin, and judge him for yourself. I won't light a candle till he's gone; there'll only be the glow of the fire; Wegg's well acquainted with the alligator, and he won't take particular notice of him. Draw your legs in, Mr. Boffin, at present I see a pair of shoes at the end of his tail. Get your head well behind his smile, Mr Boffin, and you'll lie comfortable there; you'll find plenty of room behind his smile. He's a little dusty, but he's very like you in tone. Are you right, sir?'

Boffin (lower left) seems all too conspicuous to the viewer, who must exercise some suspension of disbelief. Nevertheless, the change in perspective may account for the reptile's not being visible in the previous scene, and his general dustiness may imply that he has been stored away in a corner on the floor rather than hanging from the ceiling. The stratagem of hiding an eavesdropper behind an alligator may be derived from the John Gay-Alexander Pope-John Arthbuthnot 1717 dramatic collaboration Three Hours After Marriage, in which the butt of the farcical satire is Dr. Fossil, a natural philosopher who is being cuckolded. Regarded as obscene, the play was not performed again after its sell-out run at Drury Lane, so that Dickens could have known of it only through his reading in the British Library, or through his extensive knowledge of London stage history.

"Mr. Venus produced the document, holding on by his usual corner. Mr. Wegg, holding on by the opposite corner, sat down on the seat so lately vacated by Mr. Boffin, and looked it over."

Book 3 Chapter 14

James Mahoney

Household Edition 1875

Text Illustrated:

"Do you wish to see it?" asked Venus.

"If you please, partner," said Wegg, rubbing his hands. "I wish to see it jintly with yourself. Or, in similar words to some that was set to music some time back:

'I wish you to see it with your eyes, And I will pledge with mine.'

Turning his back and turning a key, Mr. Venus produced the document, holding on by his usual corner. Mr Wegg, holding on by the opposite corner, sat down on the seat so lately vacated by Mr. Boffin, and looked it over. "All right, sir," he slowly and unwillingly admitted, in his reluctance to loose his hold, "all right!" And greedily watched his partner as he turned his back again, and turned his key again.

"There's nothing new, I suppose?' said Venus, resuming his low chair behind the counter.

"Yes there is, sir," replied Wegg; "there was something new this morning. That foxey old grasper and griper —"

"Mr. Boffin?" inquired Venus, with a glance towards the alligator's yard or two of smile.

"Mister be blowed!" cried Wegg, yielding to his honest indignation. "Boffin. Dusty Boffin. That foxey old grunter and grinder, sir, turns into the yard this morning, to meddle with our property, a menial tool of his own, a young man by the name of Sloppy. Ecod, when I say to him, 'What do you want here, young man? This is a private yard,' he pulls out a paper from Boffin's other blackguard, the one I was passed over for. 'This is to authorize Sloppy to overlook the carting and to watch the work.' That's pretty strong, I think, Mr.Venus?"

"Remember he doesn't know yet of our claim on the property," suggested Venus.

Commentary:

The original Stone illustration of this incident drew the ire of contemporary critics:

The illustrations, moreover, are inferior to some in the last few parts, and are even worse than what we objected to in the earlier installments of the work. Mr. Stone's achievements this month are discreditable to the art of the present day, and are certainly nothing like so good as the woodcuts of the penny periodicals. ["Short Notices. Our Mutual Friend [No. 14." London Review, 3 June 1865, p. 595, rpt. in Grass, p. 210]

Thus, Mahoney may have been aware of some deficiencies in the original illustration depicting the plotters in the taxidermist's shop in Clerkenwell. For example, there is nothing very sinister in Wegg's expression, and the partners are not holding onto the will jointly, a juxtaposition in the Mahoney illustration which immediately conveys their mutual distrust. (Because the illustrator had such a specific passage in mind and conveyed his intention through the way that the mistrustful "partners" grip the document, the Chapman and Hall caption undoubtedly reflects Mahoney's intention far better than the short title in the Harper & Bros. version, which merely reiterates the chapter title.) Although Mahoney shows the taxidermist's workbench and tools (right), he does not bother to delineate the contents of the shop as he has done in "You're casting your eye round the shop, Mr. Wegg. Let me show You a light" (Book One, Chapter 7), although even this representation does not offer the fanciful detailing of the Marcus Stone and Sol Eytinge illustrations. Mahoney here is interested in the postures and intentions of the conspirators, although in the figure and facial expression of Venus he does not suggest that Venus has betrayed Wegg to Boffin, who must be hiding somewhere behind them in the darkness, his hiding place not so obvious as in the Stone original.

The murderous intentions of Bradley Headstone came as a bit of a surprise to me, as I'd thought of Eugene's wheedling and manipulative behaviour as being more the threatening of the two suitors. Or is the muser merely winding himself up, and trying to convince himself that this is what he would like to do? He may be self-deluded.

The murderous intentions of Bradley Headstone came as a bit of a surprise to me, as I'd thought of Eugene's wheedling and manipulative behaviour as being more the threatening of the two suitors. Or is the muser merely winding himself up, and trying to convince himself that this is what he would like to do? He may be self-deluded.

I loved chapter 12, about the Lammleses, and was very pleased I was not in public when I read it as the tears were running down my cheeks ... I never expected the Lammleses to provide quite such good entertainment, but really the skeleton in the cupboard was the real star for me.

I loved chapter 12, about the Lammleses, and was very pleased I was not in public when I read it as the tears were running down my cheeks ... I never expected the Lammleses to provide quite such good entertainment, but really the skeleton in the cupboard was the real star for me.Dickens can take a metaphor and really run with it! The skeleton even climbed back into the cupboard when there was no more use for it. What were they discussing? Does it matter? I'm still giggling! But yes, it moved the plot moved on nicely, and only Dickens seems to be able to do this in quite such a quirky way.

I was interested to have the question of Alfred's possible wife-beating settled, and wondered why Dickens felt the need to put this detail in. So often in Victorian novels it's all hints and subtext. I like the idea that that it might indicate Sophronia was aware that he might at some point erupt into physical violence.

But perhaps some of his readers had also asked this question?

Fledgeby is becoming increasingly odious. His deviousness surpasses even Eugene's although his ready wit (and proficiency in the whisker department) does not.

Fledgeby is becoming increasingly odious. His deviousness surpasses even Eugene's although his ready wit (and proficiency in the whisker department) does not.Chapter 14 - I never expected Venus to change sides! I did enjoy him hiding behind an alligator. Good analogy there. Never trust that toothy smile ...

Kim wrote: "Mr. Fledgeby Departs on His Errand of Mercy

Book 3 Chapter 12

Marcus Stone

Commentary:

Stone's illustration for Book 3, "A Long Lane," Chapter 12, "Meaning Mischief," appeared in the June, 1865..."

Yet another set of illustrations. Thank you Kim. It's like Christmas once a week for me.

Looking at the Fledgeby-Lammle illustration by Stone I realize how much more Hablot Browne could have done with this scene. I miss Browne's emblems in his work. Don't you think a tiny spider's web in a corner of the room, a fly upon the wall, or a strategically placed portrait with a recognizable picture would have elevated this otherwise dreary set piece?

And now to contradict myself ... I really love the Book 3 Chapter 14 Stone illustration. Much more detail, darkened shading, interesting facial expression and a great vignette in the bottom left of Boffin lurking behind the alligator. To the right of Mr. Venus can be seen the shadowy outline of at least three skulls. Now that's an informative illustration.

Book 3 Chapter 12

Marcus Stone

Commentary:

Stone's illustration for Book 3, "A Long Lane," Chapter 12, "Meaning Mischief," appeared in the June, 1865..."

Yet another set of illustrations. Thank you Kim. It's like Christmas once a week for me.

Looking at the Fledgeby-Lammle illustration by Stone I realize how much more Hablot Browne could have done with this scene. I miss Browne's emblems in his work. Don't you think a tiny spider's web in a corner of the room, a fly upon the wall, or a strategically placed portrait with a recognizable picture would have elevated this otherwise dreary set piece?

And now to contradict myself ... I really love the Book 3 Chapter 14 Stone illustration. Much more detail, darkened shading, interesting facial expression and a great vignette in the bottom left of Boffin lurking behind the alligator. To the right of Mr. Venus can be seen the shadowy outline of at least three skulls. Now that's an informative illustration.

Has anyone else realised that this is the month of the Staplehurst rail crash? Installment 14 or Book 3 chapters 11–14 were published in June 1985, and the crash was on 9th June 1865. From Wiki:

Has anyone else realised that this is the month of the Staplehurst rail crash? Installment 14 or Book 3 chapters 11–14 were published in June 1985, and the crash was on 9th June 1865. From Wiki:"Charles Dickens was with his mistress Ellen Ternan and her mother, Frances Ternan, in the first class carriage, which did not completely fall into the river bed and survived the derailment. He climbed out of the compartment through the window, rescued the Ternans and, with his flask of brandy and his hat full of water, tended to the victims, some of whom died while he was with them. Before he left with other survivors in an emergency train to London, he retrieved the manuscript of the episode of Our Mutual Friend that he was working on. The directors of the South Eastern Railway presented Dickens with a piece of plate as a token of their appreciation for his assistance in the aftermath of the accident. The experience affected Dickens greatly; he lost his voice for two weeks and he was two and a half pages short for the sixteenth episode, published in August 1865. Dickens acknowledged the incident in the novel's postscript:

"On Friday the Ninth of June in the present year, Mr and Mrs Boffin (in their manuscript dress of receiving Mr and Mrs Lammle at breakfast) were on the South-Eastern Railway with me, in a terribly destructive accident. When I had done what I could to help others, I climbed back into my carriage — nearly turned over a viaduct, and caught aslant upon the turn — to extricate the worthy couple. They were much soiled, but otherwise unhurt. [...] I remember with devout thankfulness that I can never be much nearer parting company with my readers for ever than I was then, until there shall be written against my life, the two words with which I have this day closed this book: — THE END."

Afterwards Dickens was nervous when travelling by train, using alternative means when available. He died five years to the day after the accident; his son said that 'he had never fully recovered'."

So amazing to think what we are reading could so easily have been lost - and that Dickens was such a hero :) It will be interesting too, to see if we note a change in the writing style of the next installment.

Jean wrote: "Has anyone else realised that this is the month of the Staplehurst rail crash? Installment 14 or Book 3 chapters 11–14 were published in June 1985, and the crash was on 9th June 1865. From Wiki:

Jean wrote: "Has anyone else realised that this is the month of the Staplehurst rail crash? Installment 14 or Book 3 chapters 11–14 were published in June 1985, and the crash was on 9th June 1865. From Wiki:"..."

Thanks Jean! :) I remember John saying something about the accident in an earlier thread, but I didn't realize our current place in the novel is about to coincide with the tragedy...I'm curious to see what changes we will be able to touch on?

I meant also to thank Kim! All this work in posting the illustrations and editing them so we don't find out too much - I do appreciate it :)

I meant also to thank Kim! All this work in posting the illustrations and editing them so we don't find out too much - I do appreciate it :)I too noticed a skull in the alligator illustration but can't really explain it.

Ami wrote: "I didn't realize our current place in the novel is about to coincide with the tragedy..."

Ami wrote: "I didn't realize our current place in the novel is about to coincide with the tragedy..."What strikes me about Dickens's postscript is how he tried to make light of it all, and describes it in such a tongue in cheek way.

Jean wrote: "Has anyone else realised that this is the month of the Staplehurst rail crash? Installment 14 or Book 3 chapters 11–14 were published in June 1985, and the crash was on 9th June 1865. From Wiki:

"..."

Jean

Yes. And a thanks from me too for pointing out this is the spot of the novel where the railway disaster occurred. It is hard to imagine the events of that day not affecting his writing and his life in some way or another.

"..."

Jean

Yes. And a thanks from me too for pointing out this is the spot of the novel where the railway disaster occurred. It is hard to imagine the events of that day not affecting his writing and his life in some way or another.

Jean wrote: "What strikes me about Dickens's postscript is how he tried to make light of it all, and describes it in such a tongue in cheek way. .."

Jean wrote: "What strikes me about Dickens's postscript is how he tried to make light of it all, and describes it in such a tongue in cheek way. .."But was it really? I read it again, and other than referring to the Boffins as if they were real people, I think it was rather sober. And I would think that authors, particularly those whose characters jump off the page as Dickens' do, would think of them as very real. So while on the surface he seems to be making light of it, I don't read it that way.

And as more informed 21st century readers, we have our strong suspicions about who else Dickens was with in that train. He couldn't very well mention them, so perhaps the Boffins were his way of acknowledging the other passengers and his fear for them, without mentioning them by name. Just a hunch.

Jean wrote: "Has anyone else realised that this is the month of the Staplehurst rail crash? Installment 14 or Book 3 chapters 11–14 were published in June 1985, and the crash was on 9th June 1865. From Wiki:

Jean wrote: "Has anyone else realised that this is the month of the Staplehurst rail crash? Installment 14 or Book 3 chapters 11–14 were published in June 1985, and the crash was on 9th June 1865. From Wiki:"..."

Ah, excellent, Jean. This is good to note and be reminded of going forward with the reading.

I do recall from the Tomalin and Smiley bio's that the crash had a direct impact on OMF in their view. They never, though, as I recall, detailed any specifics as to their conclusion.

Mary Lou wrote: "He couldn't very well mention them, so perhaps the Boffins were his way of acknowledging the other passengers and his fear for them..."

Mary Lou wrote: "He couldn't very well mention them, so perhaps the Boffins were his way of acknowledging the other passengers and his fear for them..."I like this insight very much. I think I read in Claire Tomalin's book that there is some evidence that he made sure Nelly and her mother were safe before rescuing other passengers.

Jean wrote: "Sorry John- crossposted. Interesting that we both remembered the Tomalin ..."

Jean wrote: "Sorry John- crossposted. Interesting that we both remembered the Tomalin ..."I'm going to go back and look at my Tomalin. It has been several months since I read it and I'd like to see if anything jumps out at me. When I read the bio, I was either not started with OMF or barely into the first few chapters.

Interestingly enough, Barnes and Noble just released for its Nook edition -- I believe just yesterday -- Les Standiford's bio on him, which is a study more so of Scrooge, Christmas, and the Dickens' life story that attaches to or springs from that.

John wrote: "Interestingly enough, Barnes and Noble just released for its Nook edition -- I believe just yesterday -- Les Standiford's bio on him, which is a study more so of Scrooge, Christmas, and the Dickens' life story that attaches to or springs from that. ..."

John wrote: "Interestingly enough, Barnes and Noble just released for its Nook edition -- I believe just yesterday -- Les Standiford's bio on him, which is a study more so of Scrooge, Christmas, and the Dickens' life story that attaches to or springs from that. ..."There's a reason for that, John -- check out the comment I just made at the Six Jolly Fellowship Porters. :-)

Ami wrote: "Jean wrote: "Has anyone else realised that this is the month of the Staplehurst rail crash? Installment 14 or Book 3 chapters 11–14 were published in June 1985, and the crash was on 9th June 1865. ..."

Well, of course, it's not a mere coincidence but a result of Everyman's, Kim's and my careful planning! ;-)

Seriously, thanks to Jean for bringing this up. It never occurred to me, but now that I think of it, it gives me a feeling of awe somehow.

Well, of course, it's not a mere coincidence but a result of Everyman's, Kim's and my careful planning! ;-)

Seriously, thanks to Jean for bringing this up. It never occurred to me, but now that I think of it, it gives me a feeling of awe somehow.

I know, me too! Now I think in the clear light of day, of course any difference in writing style will be around installment 16, the shortened one, which must have been written when this incident was preying on his mind.

I know, me too! Now I think in the clear light of day, of course any difference in writing style will be around installment 16, the shortened one, which must have been written when this incident was preying on his mind.Although this episode probably contributed to his early death, I do like to think he showed his true colours here. He was a true hero, and acknowledged as such, despite all his faults (his bad treatment of his wife, the double life he was living etc.) I wonder if I could ever have been so brave ...

I, too, like to think of Dickens as a hero, Jean! In that context, the Dickens action hero figure does make sense after all.

We have made our way to Chapter 11 of Book 3 after following Eugene up one lane and down another until we are worn out. At least our schoolmaster, Bradley Headstone is quite worn out. We're told that not only was Mr. Headstone unable to sleep this night, but neither could Miss Peecher, who I hadn't thought of for some time now, she is kept awake listening for Mr. Headstone, "the master of her heart" to return. We're told that Mr. Headstone's state of mind is murderous;