The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Our Mutual Friend

Our Mutual Friend

>

OMF, Book 2, Chp. 07-10

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Our next chapter, chapter 8 is titled, "In Which An Innocent Elopement Occurs" we find Bella is now living with the Boffins:

"That young lady was, no doubt, an acquisition to the Boffins. She was far too pretty to be unattractive anywhere, and far too quick of perception to be below the tone of her new career.

Whether it improved her heart might be a matter of taste that was open to question; but as touching another matter of taste, its improvement of her appearance and manner, there could be no question whatever."

Mr. Boffin is having a conversation with Bella about his secretary, Rokesmith. He tells her he can't make him out, Rokesmith won't meet any company at the house except Bella. When there are visitors he refuses to sit and dine with them. Bella seems to think the reason he won't meet anyone is because of her:

‘It seemed at first as if it was only Lightwood that he objected to meet. And now it seems to be everybody, except you.’

Oho! thought Miss Bella. ‘In—deed! That’s it, is it!’ For Mr Mortimer Lightwood had dined there two or three times, and she had met him elsewhere, and he had shown her some attention.

‘Rather cool in a Secretary—and Pa’s lodger—to make me the subject of his jealousy!’

That Pa’s daughter should be so contemptuous of Pa’s lodger was odd; but there were odder anomalies than that in the mind of the spoilt girl: spoilt first by poverty, and then by wealth. Be it this history’s part, however, to leave them to unravel themselves.

‘A little too much, I think,’ Miss Bella reflected scornfully, ‘to have Pa’s lodger laying claim to me, and keeping eligible people off! A little too much, indeed, to have the opportunities opened to me by Mr and Mrs Boffin, appropriated by a mere Secretary and Pa’s lodger!’

Yet it was not so very long ago that Bella had been fluttered by the discovery that this same Secretary and lodger seem to like her. Ah! but the eminently aristocratic mansion and Mrs Boffin’s dressmaker had not come into play then."

Oh Bella, please don't be that way. In Bella's opinion he is a very intrusive person, probably brought on by his talking about her family. She is not at all pleased when he asks whether there is any message he can take to her parents. He tells her they ask often about her and he tells them what little he knows. She tells him she has no message for them because she is planning on visiting the next day. We then have this:

"He lingered a moment, as though to give her the opportunity of prolonging the conversation if she wished. As she remained silent, he left her. Two incidents of the little interview were felt by Miss Bella herself, when alone again, to be very curious. The first was, that he unquestionably left her with a penitent air upon her, and a penitent feeling in her heart. The second was, that she had not an intention or a thought of going home, until she had announced it to him as a settled design.

‘What can I mean by it, or what can he mean by it?’ was her mental inquiry: ‘He has no right to any power over me, and how do I come to mind him when I don’t care for him?’

They are waiting for her the next day when she arrives home. Her mother and sister that is. I did enjoy her sister through this visit.

"The family room looked very small and very mean, and the downward staircase by which it was attained looked very narrow and very crooked. The little house and all its arrangements were a poor contrast to the eminently aristocratic dwelling. ‘I can hardly believe,’ thought Bella, ‘that I ever did endure life in this place!’

Gloomy majesty on the part of Mrs Wilfer, and native pertness on the part of Lavvy, did not mend the matter. Bella really stood in natural need of a little help, and she got none.

‘This,’ said Mrs Wilfer, presenting a cheek to be kissed, as sympathetic and responsive as the back of the bowl of a spoon, ‘is quite an honour! You will probably find your sister Lavvy grown, Bella.’

‘Ma,’ Miss Lavinia interposed, ‘there can be no objection to your being aggravating, because Bella richly deserves it; but I really must request that you will not drag in such ridiculous nonsense as my having grown when I am past the growing age.’

The three of them get into a quarrel about the Boffins, eventually all three women have burst into tears when Mr. Rokesmith enters. He doesn't say anything about what he has walked in on but tells Bella he is there with a purse for her from Mr. Boffin. She now goes in search of her father who works at Chicksey Veneering and Stobbles, and once finding it takes Mr. Wilfer to lunch with her. It is easy to tell Bella gets along much better with her father than her mother or her sister.

I like to have you all to myself to-day. I was always your little favourite at home, and you were always mine. We have run away together often, before now; haven’t we, Pa?’

‘Ah, to be sure we have! Many a Sunday when your mother was—was a little liable to it,’ repeating his former delicate expression after pausing to cough.

‘Yes, and I am afraid I was seldom or never as good as I ought to have been, Pa. I made you carry me, over and over again, when you should have made me walk; and I often drove you in harness, when you would much rather have sat down and read your news-paper: didn’t I?’

‘Sometimes, sometimes. But Lor, what a child you were! What a companion you were!’

‘Companion? That’s just what I want to be to-day, Pa.’

And they do spend the day together, having lunch, watching the ships and steamboats go down the river, buying new clothes for her father, and finally supper together. Bella tells her father that she must have money, she finds that she can't steal it, borrow it, beg for it, so she'll have to marry it. Her father is shocked and tells her that he knows she doesn't mean it, but she insists it is true. We end with this:

"After which, she tugged at his coat with both hands, and pulled him all askew in buttoning that garment over the precious waistcoat pocket, and then tied her dimples into her bonnet-strings in a very knowing way, and took him back to London. Arrived at Mr Boffin’s door, she set him with his back against it, tenderly took him by the ears as convenient handles for her purpose, and kissed him until he knocked muffled double knocks at the door with the back of his head. That done, she once more reminded him of their compact and gaily parted from him.

Not so gaily, however, but that tears filled her eyes as he went away down the dark street. Not so gaily, but that she several times said, ‘Ah, poor little Pa! Ah, poor dear struggling shabby little Pa!’ before she took heart to knock at the door. Not so gaily, but that the brilliant furniture seemed to stare her out of countenance as if it insisted on being compared with the dingy furniture at home. Not so gaily, but that she fell into very low spirits sitting late in her own room, and very heartily wept, as she wished, now that the deceased old John Harmon had never made a will about her, now that the deceased young John Harmon had lived to marry her. ‘Contradictory things to wish,’ said Bella, ‘but my life and fortunes are so contradictory altogether that what can I expect myself to be!’

"That young lady was, no doubt, an acquisition to the Boffins. She was far too pretty to be unattractive anywhere, and far too quick of perception to be below the tone of her new career.

Whether it improved her heart might be a matter of taste that was open to question; but as touching another matter of taste, its improvement of her appearance and manner, there could be no question whatever."

Mr. Boffin is having a conversation with Bella about his secretary, Rokesmith. He tells her he can't make him out, Rokesmith won't meet any company at the house except Bella. When there are visitors he refuses to sit and dine with them. Bella seems to think the reason he won't meet anyone is because of her:

‘It seemed at first as if it was only Lightwood that he objected to meet. And now it seems to be everybody, except you.’

Oho! thought Miss Bella. ‘In—deed! That’s it, is it!’ For Mr Mortimer Lightwood had dined there two or three times, and she had met him elsewhere, and he had shown her some attention.

‘Rather cool in a Secretary—and Pa’s lodger—to make me the subject of his jealousy!’

That Pa’s daughter should be so contemptuous of Pa’s lodger was odd; but there were odder anomalies than that in the mind of the spoilt girl: spoilt first by poverty, and then by wealth. Be it this history’s part, however, to leave them to unravel themselves.

‘A little too much, I think,’ Miss Bella reflected scornfully, ‘to have Pa’s lodger laying claim to me, and keeping eligible people off! A little too much, indeed, to have the opportunities opened to me by Mr and Mrs Boffin, appropriated by a mere Secretary and Pa’s lodger!’

Yet it was not so very long ago that Bella had been fluttered by the discovery that this same Secretary and lodger seem to like her. Ah! but the eminently aristocratic mansion and Mrs Boffin’s dressmaker had not come into play then."

Oh Bella, please don't be that way. In Bella's opinion he is a very intrusive person, probably brought on by his talking about her family. She is not at all pleased when he asks whether there is any message he can take to her parents. He tells her they ask often about her and he tells them what little he knows. She tells him she has no message for them because she is planning on visiting the next day. We then have this:

"He lingered a moment, as though to give her the opportunity of prolonging the conversation if she wished. As she remained silent, he left her. Two incidents of the little interview were felt by Miss Bella herself, when alone again, to be very curious. The first was, that he unquestionably left her with a penitent air upon her, and a penitent feeling in her heart. The second was, that she had not an intention or a thought of going home, until she had announced it to him as a settled design.

‘What can I mean by it, or what can he mean by it?’ was her mental inquiry: ‘He has no right to any power over me, and how do I come to mind him when I don’t care for him?’

They are waiting for her the next day when she arrives home. Her mother and sister that is. I did enjoy her sister through this visit.

"The family room looked very small and very mean, and the downward staircase by which it was attained looked very narrow and very crooked. The little house and all its arrangements were a poor contrast to the eminently aristocratic dwelling. ‘I can hardly believe,’ thought Bella, ‘that I ever did endure life in this place!’

Gloomy majesty on the part of Mrs Wilfer, and native pertness on the part of Lavvy, did not mend the matter. Bella really stood in natural need of a little help, and she got none.

‘This,’ said Mrs Wilfer, presenting a cheek to be kissed, as sympathetic and responsive as the back of the bowl of a spoon, ‘is quite an honour! You will probably find your sister Lavvy grown, Bella.’

‘Ma,’ Miss Lavinia interposed, ‘there can be no objection to your being aggravating, because Bella richly deserves it; but I really must request that you will not drag in such ridiculous nonsense as my having grown when I am past the growing age.’

The three of them get into a quarrel about the Boffins, eventually all three women have burst into tears when Mr. Rokesmith enters. He doesn't say anything about what he has walked in on but tells Bella he is there with a purse for her from Mr. Boffin. She now goes in search of her father who works at Chicksey Veneering and Stobbles, and once finding it takes Mr. Wilfer to lunch with her. It is easy to tell Bella gets along much better with her father than her mother or her sister.

I like to have you all to myself to-day. I was always your little favourite at home, and you were always mine. We have run away together often, before now; haven’t we, Pa?’

‘Ah, to be sure we have! Many a Sunday when your mother was—was a little liable to it,’ repeating his former delicate expression after pausing to cough.

‘Yes, and I am afraid I was seldom or never as good as I ought to have been, Pa. I made you carry me, over and over again, when you should have made me walk; and I often drove you in harness, when you would much rather have sat down and read your news-paper: didn’t I?’

‘Sometimes, sometimes. But Lor, what a child you were! What a companion you were!’

‘Companion? That’s just what I want to be to-day, Pa.’

And they do spend the day together, having lunch, watching the ships and steamboats go down the river, buying new clothes for her father, and finally supper together. Bella tells her father that she must have money, she finds that she can't steal it, borrow it, beg for it, so she'll have to marry it. Her father is shocked and tells her that he knows she doesn't mean it, but she insists it is true. We end with this:

"After which, she tugged at his coat with both hands, and pulled him all askew in buttoning that garment over the precious waistcoat pocket, and then tied her dimples into her bonnet-strings in a very knowing way, and took him back to London. Arrived at Mr Boffin’s door, she set him with his back against it, tenderly took him by the ears as convenient handles for her purpose, and kissed him until he knocked muffled double knocks at the door with the back of his head. That done, she once more reminded him of their compact and gaily parted from him.

Not so gaily, however, but that tears filled her eyes as he went away down the dark street. Not so gaily, but that she several times said, ‘Ah, poor little Pa! Ah, poor dear struggling shabby little Pa!’ before she took heart to knock at the door. Not so gaily, but that the brilliant furniture seemed to stare her out of countenance as if it insisted on being compared with the dingy furniture at home. Not so gaily, but that she fell into very low spirits sitting late in her own room, and very heartily wept, as she wished, now that the deceased old John Harmon had never made a will about her, now that the deceased young John Harmon had lived to marry her. ‘Contradictory things to wish,’ said Bella, ‘but my life and fortunes are so contradictory altogether that what can I expect myself to be!’

Chapter 9 is titled, "In Which The Orphan Makes His Will", which I suppose is a fine name for a chapter that goes along like this one goes along. This is the chapter Tristram was so delighted to find would be my chapter. He may have even arranged it this way. And here we go, the chapter begins with Sloppy coming to the house,

"The Secretary, working in the Dismal Swamp betimes next morning, was informed that a youth waited in the hall who gave the name of Sloppy. The footman who communicated this intelligence made a decent pause before uttering the name, to express that it was forced on his reluctance by the youth in question, and that if the youth had had the good sense and good taste to inherit some other name it would have spared the feelings of him the bearer."

Rokesmith is delighted to see him, telling him he had been expecting him. Sloppy tells him that he meant to come earlier but Johnny had been ill and he was waiting until the boy was better to come. Sloppy says that Johnny isn't any better, telling him that he must have "took ‘em from the Minders.’ . This comment completely confused me until I realized the word was "minders" and not "miner", I guess living near the coal country of Pennsylvania that's what my eyes saw and I spent a few confused minutes wondering how Johnny got sick from a coal miner. But sick he is, coal miner or not and as Sloppy tells us it had "come out upon him and partickler his chest." As to what it may be:

"John Rokesmith hoped the child had had medical attendance? Oh yes, said Sloppy, he had been took to the doctor’s shop once. And what did the doctor call it? Rokesmith asked him.

After some perplexed reflection, Sloppy answered brightening, ‘He called it something as wos wery long for spots.’ Rokesmith suggested measles. ‘No,’ said Sloppy with confidence, ‘ever so much longer than them, sir!’ (Mr Sloppy was elevated by this fact, and seemed to consider that it reflected credit on the poor little patient.)

‘Mrs Boffin will be sorry to hear this,’ said Rokesmith."

Does anyone know what this sickness is? Any of the ones I can think of wouldn't have very long names for spots. We soon find Mrs Boffin, Rokesmith, Sloppy, and Bella on their way to the home of Mrs. Higden to try to help Johnny. I don't know how others feel and maybe I would have done the same thing Mrs. Boffin did, but when I read this and Mrs. Boffin asked why they hadn't let her know how sick he was, I wondered why she didn't go herself and check in on them once in awhile. Arriving there they find Johnny just as sick as Sloppy had told them. When Betty hears they want to take the child where he can be better taken care of, she rushes to the door and tries to flee with Johnny in her arms. With her fear of poorhouses it takes them awhile to make themselves understood that it is not to a poor house they are taking him, but to a children's hospital.

‘Now, see, Betty,’ pursued the sweet compassionate soul, holding the hand kindly, ‘what I really did mean, and what I should have begun by saying out, if I had only been a little wiser and handier. We want to move Johnny to a place where there are none but children; a place set up on purpose for sick children; where the good doctors and nurses pass their lives with children, talk to none but children, touch none but children, comfort and cure none but children.’

‘Is there really such a place?’ asked the old woman, with a gaze of wonder.

‘Yes, Betty, on my word, and you shall see it. If my home was a better place for the dear boy, I’d take him to it; but indeed indeed it’s not.’

‘You shall take him,’ returned Betty, fervently kissing the comforting hand, ‘where you will, my deary. I am not so hard, but that I believe your face and voice, and I will, as long as I can see and hear.’

And there they take him, and there he is seen by the doctors, and by the nurses, and there he is in a little quiet bed, and there the toys, Noah’s ark, the noble steed, and the yellow bird are around him to cheer him, and there they leave him to come back in the morning, and there he gives his toys to the boy in the next bed, and there he dies. I hated this chapter.

"The Secretary, working in the Dismal Swamp betimes next morning, was informed that a youth waited in the hall who gave the name of Sloppy. The footman who communicated this intelligence made a decent pause before uttering the name, to express that it was forced on his reluctance by the youth in question, and that if the youth had had the good sense and good taste to inherit some other name it would have spared the feelings of him the bearer."

Rokesmith is delighted to see him, telling him he had been expecting him. Sloppy tells him that he meant to come earlier but Johnny had been ill and he was waiting until the boy was better to come. Sloppy says that Johnny isn't any better, telling him that he must have "took ‘em from the Minders.’ . This comment completely confused me until I realized the word was "minders" and not "miner", I guess living near the coal country of Pennsylvania that's what my eyes saw and I spent a few confused minutes wondering how Johnny got sick from a coal miner. But sick he is, coal miner or not and as Sloppy tells us it had "come out upon him and partickler his chest." As to what it may be:

"John Rokesmith hoped the child had had medical attendance? Oh yes, said Sloppy, he had been took to the doctor’s shop once. And what did the doctor call it? Rokesmith asked him.

After some perplexed reflection, Sloppy answered brightening, ‘He called it something as wos wery long for spots.’ Rokesmith suggested measles. ‘No,’ said Sloppy with confidence, ‘ever so much longer than them, sir!’ (Mr Sloppy was elevated by this fact, and seemed to consider that it reflected credit on the poor little patient.)

‘Mrs Boffin will be sorry to hear this,’ said Rokesmith."

Does anyone know what this sickness is? Any of the ones I can think of wouldn't have very long names for spots. We soon find Mrs Boffin, Rokesmith, Sloppy, and Bella on their way to the home of Mrs. Higden to try to help Johnny. I don't know how others feel and maybe I would have done the same thing Mrs. Boffin did, but when I read this and Mrs. Boffin asked why they hadn't let her know how sick he was, I wondered why she didn't go herself and check in on them once in awhile. Arriving there they find Johnny just as sick as Sloppy had told them. When Betty hears they want to take the child where he can be better taken care of, she rushes to the door and tries to flee with Johnny in her arms. With her fear of poorhouses it takes them awhile to make themselves understood that it is not to a poor house they are taking him, but to a children's hospital.

‘Now, see, Betty,’ pursued the sweet compassionate soul, holding the hand kindly, ‘what I really did mean, and what I should have begun by saying out, if I had only been a little wiser and handier. We want to move Johnny to a place where there are none but children; a place set up on purpose for sick children; where the good doctors and nurses pass their lives with children, talk to none but children, touch none but children, comfort and cure none but children.’

‘Is there really such a place?’ asked the old woman, with a gaze of wonder.

‘Yes, Betty, on my word, and you shall see it. If my home was a better place for the dear boy, I’d take him to it; but indeed indeed it’s not.’

‘You shall take him,’ returned Betty, fervently kissing the comforting hand, ‘where you will, my deary. I am not so hard, but that I believe your face and voice, and I will, as long as I can see and hear.’

And there they take him, and there he is seen by the doctors, and by the nurses, and there he is in a little quiet bed, and there the toys, Noah’s ark, the noble steed, and the yellow bird are around him to cheer him, and there they leave him to come back in the morning, and there he gives his toys to the boy in the next bed, and there he dies. I hated this chapter.

Chapter 10 is titled "A Successor" and we begin with the funeral of Johnny:

Some of the Reverend Frank Milvey’s brethren had found themselves exceedingly uncomfortable in their minds, because they were required to bury the dead too hopefully. But, the Reverend Frank, inclining to the belief that they were required to do one or two other things (say out of nine-and-thirty) calculated to trouble their consciences rather more if they would think as much about them, held his peace.

Indeed, the Reverend Frank Milvey was a forbearing man, who noticed many sad warps and blights in the vineyard wherein he worked, and did not profess that they made him savagely wise. He only learned that the more he himself knew, in his little limited human way, the better he could distantly imagine what Omniscience might know.

Wherefore, if the Reverend Frank had had to read the words that troubled some of his brethren, and profitably touched innumerable hearts, in a worse case than Johnny’s, he would have done so out of the pity and humility of his soul. Reading them over Johnny, he thought of his own six children, but not of his poverty, and read them with dimmed eyes. And very seriously did he and his bright little wife, who had been listening, look down into the small grave and walk home arm-in-arm.

I looked up what this problem some of the clergy had with the words of the funeral and found this:

Some clergymen in the 1860s were unhappy about uttering the assurance of eternal life over the graves of those who obviously did not hope of the Resurrection to eternal life.

My brother used to take drugs, a lot of drugs, and not the kind I do for seizures and migraines and such things, not only did he seem to enjoy this stupid hobby, but he also sold the stuff to other people. We had a very hard time getting along, especially when he would ask me to give him any left over medications I may have, but we managed to put up with each other.

When he died and we were at the funeral there were the usual funeral things said, the Lord's Prayer, the 23rd Psalm, the hope of the resurrection, things like that, and I wondered if he really did have this "hope". I only wondered it briefly though because I did what I often do, I just let it all up to God. Anyway, Johnny is now gone and we find there is grief in the new house, but happiness in the Bower:

"There was grief in the aristocratic house, and there was joy in the Bower. Mr Wegg argued, if an orphan were wanted, was he not an orphan himself; and could a better be desired?

And why go beating about Brentford bushes, seeking orphans forsooth who had established no claims upon you and made no sacrifices for you, when here was an orphan ready to your hand who had given up in your cause, Miss Elizabeth, Master George, Aunt Jane, and Uncle Parker?

Mr Wegg chuckled, consequently, when he heard the tidings. Nay, it was afterwards affirmed by a witness who shall at present be nameless, that in the seclusion of the Bower he poked out his wooden leg, in the stage-ballet manner, and executed a taunting or triumphant pirouette on the genuine leg remaining to him."

I wonder if he really believed the things he said. Here comes a paragraph that has me thinking it may be important at some time, I don't know why:

"John Rokesmith’s manner towards Mrs Boffin at this time, was more the manner of a young man towards a mother, than that of a Secretary towards his employer’s wife. It had always been marked by a subdued affectionate deference that seemed to have sprung up on the very day of his engagement; whatever was odd in her dress or her ways had seemed to have no oddity for him; he had sometimes borne a quietly-amused face in her company, but still it had seemed as if the pleasure her genial temper and radiant nature yielded him, could have been quite as naturally expressed in a tear as in a smile. The completeness of his sympathy with her fancy for having a little John Harmon to protect and rear, he had shown in every act and word, and now that the kind fancy was disappointed, he treated it with a manly tenderness and respect for which she could hardly thank him enough."

Mrs. Boffin calls them, Mr. Boffin, Rokesmith, and Bella together and tells them that she does not plan to call another orphan John Harman, she finds the name to be unlucky, and asks them what they think. Mr. Boffin agrees with his wife, Rokesmith says the name is unfortunate and perhaps it should be let to die out, and Bella says since they had given the name to the poor child, and as the poor child took so lovingly to her, she would not like another child to be called by that name. And it is now decided the name will end. Mrs. Boffin says instead of finding another child, a pretty child to her liking, she is this time going to help a boy that really needs their help. At this point Sloppy arrives and the chapter ends with this:

‘Come forward, Sloppy. Should you like to dine here every day?’

‘Off of all four on ‘em, mum? O mum!’ Sloppy’s feelings obliged him to squeeze his hat, and contract one leg at the knee.

‘Yes. And should you like to be always taken care of here, if you were industrious and deserving?’

‘Oh, mum!—But there’s Mrs Higden,’ said Sloppy, checking himself in his raptures, drawing back, and shaking his head with very serious meaning. ‘There’s Mrs Higden. Mrs Higden goes before all. None can ever be better friends to me than Mrs Higden’s been. And she must be turned for, must Mrs Higden. Where would Mrs Higden be if she warn’t turned for!’ At the mere thought of Mrs Higden in this inconceivable affliction, Mr Sloppy’s countenance became pale, and manifested the most distressful emotions.

‘You are as right as right can be, Sloppy,’ said Mrs Boffin ‘and far be it from me to tell you otherwise. It shall be seen to. If Betty Higden can be turned for all the same, you shall come here and be taken care of for life, and be made able to keep her in other ways than the turning.’

‘Even as to that, mum,’ answered the ecstatic Sloppy, ‘the turning might be done in the night, don’t you see? I could be here in the day, and turn in the night. I don’t want no sleep, I don’t. Or even if I any ways should want a wink or two,’ added Sloppy, after a moment’s apologetic reflection, ‘I could take ‘em turning. I’ve took ‘em turning many a time, and enjoyed ‘em wonderful!’

On the grateful impulse of the moment, Mr Sloppy kissed Mrs. Boffin’s hand, and then detaching himself from that good creature that he might have room enough for his feelings, threw back his head, opened his mouth wide, and uttered a dismal howl. It was creditable to his tenderness of heart, but suggested that he might on occasion give some offence to the neighbours: the rather, as the footman looked in, and begged pardon, finding he was not wanted, but excused himself; on the ground ‘that he thought it was Cats.’

Some of the Reverend Frank Milvey’s brethren had found themselves exceedingly uncomfortable in their minds, because they were required to bury the dead too hopefully. But, the Reverend Frank, inclining to the belief that they were required to do one or two other things (say out of nine-and-thirty) calculated to trouble their consciences rather more if they would think as much about them, held his peace.

Indeed, the Reverend Frank Milvey was a forbearing man, who noticed many sad warps and blights in the vineyard wherein he worked, and did not profess that they made him savagely wise. He only learned that the more he himself knew, in his little limited human way, the better he could distantly imagine what Omniscience might know.

Wherefore, if the Reverend Frank had had to read the words that troubled some of his brethren, and profitably touched innumerable hearts, in a worse case than Johnny’s, he would have done so out of the pity and humility of his soul. Reading them over Johnny, he thought of his own six children, but not of his poverty, and read them with dimmed eyes. And very seriously did he and his bright little wife, who had been listening, look down into the small grave and walk home arm-in-arm.

I looked up what this problem some of the clergy had with the words of the funeral and found this:

Some clergymen in the 1860s were unhappy about uttering the assurance of eternal life over the graves of those who obviously did not hope of the Resurrection to eternal life.

My brother used to take drugs, a lot of drugs, and not the kind I do for seizures and migraines and such things, not only did he seem to enjoy this stupid hobby, but he also sold the stuff to other people. We had a very hard time getting along, especially when he would ask me to give him any left over medications I may have, but we managed to put up with each other.

When he died and we were at the funeral there were the usual funeral things said, the Lord's Prayer, the 23rd Psalm, the hope of the resurrection, things like that, and I wondered if he really did have this "hope". I only wondered it briefly though because I did what I often do, I just let it all up to God. Anyway, Johnny is now gone and we find there is grief in the new house, but happiness in the Bower:

"There was grief in the aristocratic house, and there was joy in the Bower. Mr Wegg argued, if an orphan were wanted, was he not an orphan himself; and could a better be desired?

And why go beating about Brentford bushes, seeking orphans forsooth who had established no claims upon you and made no sacrifices for you, when here was an orphan ready to your hand who had given up in your cause, Miss Elizabeth, Master George, Aunt Jane, and Uncle Parker?

Mr Wegg chuckled, consequently, when he heard the tidings. Nay, it was afterwards affirmed by a witness who shall at present be nameless, that in the seclusion of the Bower he poked out his wooden leg, in the stage-ballet manner, and executed a taunting or triumphant pirouette on the genuine leg remaining to him."

I wonder if he really believed the things he said. Here comes a paragraph that has me thinking it may be important at some time, I don't know why:

"John Rokesmith’s manner towards Mrs Boffin at this time, was more the manner of a young man towards a mother, than that of a Secretary towards his employer’s wife. It had always been marked by a subdued affectionate deference that seemed to have sprung up on the very day of his engagement; whatever was odd in her dress or her ways had seemed to have no oddity for him; he had sometimes borne a quietly-amused face in her company, but still it had seemed as if the pleasure her genial temper and radiant nature yielded him, could have been quite as naturally expressed in a tear as in a smile. The completeness of his sympathy with her fancy for having a little John Harmon to protect and rear, he had shown in every act and word, and now that the kind fancy was disappointed, he treated it with a manly tenderness and respect for which she could hardly thank him enough."

Mrs. Boffin calls them, Mr. Boffin, Rokesmith, and Bella together and tells them that she does not plan to call another orphan John Harman, she finds the name to be unlucky, and asks them what they think. Mr. Boffin agrees with his wife, Rokesmith says the name is unfortunate and perhaps it should be let to die out, and Bella says since they had given the name to the poor child, and as the poor child took so lovingly to her, she would not like another child to be called by that name. And it is now decided the name will end. Mrs. Boffin says instead of finding another child, a pretty child to her liking, she is this time going to help a boy that really needs their help. At this point Sloppy arrives and the chapter ends with this:

‘Come forward, Sloppy. Should you like to dine here every day?’

‘Off of all four on ‘em, mum? O mum!’ Sloppy’s feelings obliged him to squeeze his hat, and contract one leg at the knee.

‘Yes. And should you like to be always taken care of here, if you were industrious and deserving?’

‘Oh, mum!—But there’s Mrs Higden,’ said Sloppy, checking himself in his raptures, drawing back, and shaking his head with very serious meaning. ‘There’s Mrs Higden. Mrs Higden goes before all. None can ever be better friends to me than Mrs Higden’s been. And she must be turned for, must Mrs Higden. Where would Mrs Higden be if she warn’t turned for!’ At the mere thought of Mrs Higden in this inconceivable affliction, Mr Sloppy’s countenance became pale, and manifested the most distressful emotions.

‘You are as right as right can be, Sloppy,’ said Mrs Boffin ‘and far be it from me to tell you otherwise. It shall be seen to. If Betty Higden can be turned for all the same, you shall come here and be taken care of for life, and be made able to keep her in other ways than the turning.’

‘Even as to that, mum,’ answered the ecstatic Sloppy, ‘the turning might be done in the night, don’t you see? I could be here in the day, and turn in the night. I don’t want no sleep, I don’t. Or even if I any ways should want a wink or two,’ added Sloppy, after a moment’s apologetic reflection, ‘I could take ‘em turning. I’ve took ‘em turning many a time, and enjoyed ‘em wonderful!’

On the grateful impulse of the moment, Mr Sloppy kissed Mrs. Boffin’s hand, and then detaching himself from that good creature that he might have room enough for his feelings, threw back his head, opened his mouth wide, and uttered a dismal howl. It was creditable to his tenderness of heart, but suggested that he might on occasion give some offence to the neighbours: the rather, as the footman looked in, and begged pardon, finding he was not wanted, but excused himself; on the ground ‘that he thought it was Cats.’

Kim, Forgive me if I over-respond to your first question, the one about the chapter title "In which a friendly move is originated". I agree, the word "move" is odd. It doesn't sound Dickensian or Victorian, to me.

Kim, Forgive me if I over-respond to your first question, the one about the chapter title "In which a friendly move is originated". I agree, the word "move" is odd. It doesn't sound Dickensian or Victorian, to me. But first, doesn't it feel like Dickens is having fun with his titles, especially the three in a row which begin with the "In which" prefix? I just now found that name:

The second paragraph refers to the "In Which..." prefix:

http://ask.metafilter.com/6146/Victor...

Dickens' trio of In Which titles calls up the old 18c and 19c convention of spelling out the plot in the chapter title. As I also just learned, this was done to entice readers to purchase the printed product:

http://allthetropes.wikia.com/wiki/In...

I think Dickens is pulling our leg in "In which A friendly move is originated". There is nothing "friendly" going on in chapter 7. Wegg is enlisting Mr Venus' help to do some moving in the dust piles, moving that he can't do. It is to be done without drawing attention. It has to do with "papers" (word supplied conVENiently by Mr Venus) that could have been hidden. And it's a "partnership" of the two men.

Wegg calls Rokesmith a man with "an underhanded mind" and our Mr Boffin is "the worm of the hour". Seems like an unfriendly move has begun.

As for the word "move"... I don't know. Maybe in the sense of A chess MOVE?

Yes, I would strongly suggest that "move" is to be seen in the light of a move in a strategy game. And the adjective "friendly", well, Mr Wegg tries his best to cover up his purely selfish motives with a touch of fighting for justice.

I really love Mr Wegg's poetry! Fancy calling Mr Boffin "the minion of fortune" and "the worm of the hour"! It's daring, and it's poetic!

I really love Mr Wegg's poetry! Fancy calling Mr Boffin "the minion of fortune" and "the worm of the hour"! It's daring, and it's poetic!

I'll cast another vote for "move" being related somehow to strategy. "Friendly" is an interesting choice of words as well. My guess is Dickens is being ironic here.

With Wegg now partnered with Venus we have yet another grouping or team of two characters. It seems that these teams of characters are functioning as players on a board game of strategy. We have Mortimer and Eugene, Charley and Headstone - interesting how Dickens pitted these "teams" against each other last chapter - as well as the husband and wife team of the Lammles, the Podsnaps the Veneerings and the Boffins. Let's not forget the team of Lizzie Hexam and Jenny Wren.

Somehow I don't think it is Dickens's intention to make many of the interrelationships among these parings that friendly.

With Wegg now partnered with Venus we have yet another grouping or team of two characters. It seems that these teams of characters are functioning as players on a board game of strategy. We have Mortimer and Eugene, Charley and Headstone - interesting how Dickens pitted these "teams" against each other last chapter - as well as the husband and wife team of the Lammles, the Podsnaps the Veneerings and the Boffins. Let's not forget the team of Lizzie Hexam and Jenny Wren.

Somehow I don't think it is Dickens's intention to make many of the interrelationships among these parings that friendly.

Chapter 7 has its centre and focus on dust. Heaps of it. Mounds of it. When the question of what could be hidden in the dust mounds and thus what could be subsequently found in those same mounds is raised I think we have found a centre for our plot. We are told that Harmon was "likely to take such opportunities as this place offered, of stowing money, valuables, maybe papers." And so the deal is made that Venus and Wegg will look together.

Is it coincidence that shortly after this dusty deal ( sorry but I couldn't resist that last phrase :-)) ) Rokesmith shows up? Of all the characters in this novel so far, he is the one with the least backstory, the one who is the most enigmatic. Interesting.

Is it coincidence that shortly after this dusty deal ( sorry but I couldn't resist that last phrase :-)) ) Rokesmith shows up? Of all the characters in this novel so far, he is the one with the least backstory, the one who is the most enigmatic. Interesting.

Chapter 8 gives us another pairing to add to the ones discussed in Chapter 7. This time, however, it is a rather twisted pairing since Dickens pairs a dead person with another dead person. We read that Bella wished "that the deceased old John Harmon had never made a will about her, now that the deceased young John Harmon had lived to marry her." Two John Harmons, both dead.

Bella does, however, perceive that Rokesmith has an interest in her, but being a mere clerk, he has no prospects. Bella candidly admits to herself and her father "I am so mercenary!" This admission places Bella in an interesting position. Who would be worthy of her? Who would, or does have the resources to meet her criteria for love?

Bella does, however, perceive that Rokesmith has an interest in her, but being a mere clerk, he has no prospects. Bella candidly admits to herself and her father "I am so mercenary!" This admission places Bella in an interesting position. Who would be worthy of her? Who would, or does have the resources to meet her criteria for love?

Here is something else from Jane Smiley's biography of Dickens:

Here is something else from Jane Smiley's biography of Dickens:While he was working up Our Mutual Friend, he complained to Forster that he didn't quite know what he was getting at.

"Good-evening, Mr. Wegg. The yard-gate lock should be looked to, if you please; it don't catch."

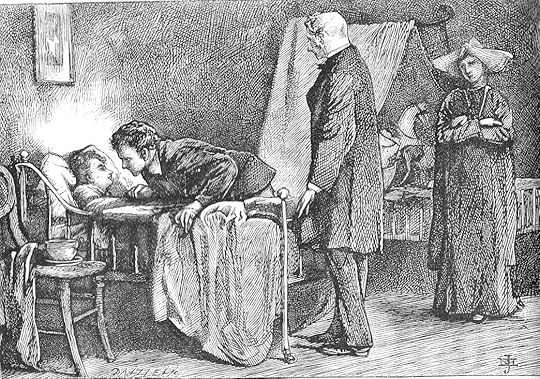

Book 2 Chapter 7

1875 Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

"Pray is Mr. Silas Wegg here? Oh! I see him!"

"The friendly movers might not have been quite at their ease, even though the visitor had entered in the usual manner. But, leaning on the breast-high window, and staring in out of the darkness, they find the visitor extremely embarrassing. Especially Mr. Venus: who removes his pipe, draws back his head, and stares at the starer, as if it were his own Hindoo baby come to fetch him home.

"Good evening, Mr. Wegg. The yard gate-lock should be looked to, if you please; it don't catch."

"Is it Mr. Rokesmith?" falters Wegg.

"It is Mr. Rokesmith. Don't let me disturb you. I am not coming in. I have only a message for you, which I undertook to deliver on my way home to my lodgings. I was in two minds about coming beyond the gate without ringing: not knowing but you might have a dog about."

"I wish I had," mutters Wegg, with his back turned as he rose from his chair. St! Hush! The talking-over stranger, Mr. Venus."

"Is that any one I know?" inquires the staring Secretary.

"No, Mr. Rokesmith. Friend of mine. Passing the evening with me."

"Oh! I beg his pardon. Mr. Boffin wishes you to know that he does not expect you to stay at home any evening, on the chance of his coming. It has occurred to him that he may, without intending it, have been a tie upon you. In future, if he should come without notice, he will take his chance of finding you, and it will be all the same to him if he does not. I undertook to tell you on my way. That's all."

Commentary:

The scene is the exterior of Boffin's Bower after sunset, when Rokesmith, leaving a message for Wegg, unconsciously interrupts the plotting of Wegg and the taxidermist, Mr. Venus, to rifle the mounds for valuables. There is no Marcus Stone antecedent for this illustration from the original serial. The significant part of this dark plate is the caption which, taken with the middle-class, professional appearance of Rokesmith, reveals a power relationship in which Wegg is clearly the inferior as the command to repair the latch does not come from Rokesmith's superior, but from Rokesmith himself.

The illustration underscores Wegg's increasing jealousy of the Boffins' new secretary, John Rokesmith. The meeting of the secretary, Wegg, and Venus occurs at Boffin's Bower, of which Wegg is now the caretaker, a choice inferior to that of previous illustrators Marcus Stone and Sol Eytinge, Jr.. The message that Rokesmith brings from Boffin concerns the habit that their employer has developed of merely dropping by for his evening reading of Gibbon's The Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire. The illustration offers only thumbnails of Wegg and Venus, while the face of John Rokesmith remains obscured by the pose that Mahoney has selected. Wegg is indeed "faltering" and even stunned by the timely arrival of the Secretary, for he and his accomplice were just about to seal their pact in yet another draft ofJamaican rum.

"Pa's Lodger and Pa's Daughter"

Book 2 Chapter 8

Marcus Stone

Commentary:

The young man (Rokesmith) offers to carry messages home for the young lady who has had the good fortune to be taken up by the Boffins and translated to their mansion, where Rokesmith has just been hired as Mrs. Boffin's "Secretary." Clearly his moral intention in the text is to upbraid the wilful Bella for neglecting her own family since the Boffins have translated her to a loftier sphere. His subtle goading provokes Bella to visit her parents (in the Boffins' coach, of course) and buy her father a new wardrobe.

The passage illustrated involves Bella's incorrectly decoding Rokesmith's motivation and haughtily appraising him:

'Rather cool in a Secretary — and Pa's lodger — to make me the subject of his jealousy!'

That Pa's daughter should be so contemptuous of Pa's lodger was odd; but there were odder anomalies than that in the mind of the spoilt girl: the doubly spilt girl: spoilt first by poverty, and then by wealth. Be it this history's part, however, to leave them to unravel themselves.

'A little too much, I think,' Miss Bella reflected scornfully, 'to have Pa's lodger laying claim to me, and keeping eligible people [i. e., the attorney Mortimer Lightwood] off! A little too much, indeed, to have the opportunities opened to me by Mr. and Mrs. Boffin, appropriated by a mere Secretary and Pa's lodger.'

The illustration introduces that staple of the Dickens novel: romance between two physically attractive young adults. What is different is Dickens's using the third-person limited omniscient to expose Bella's class-consciousness and vanity, making her a parallel figure to Estella in Great Expectations (1861).

The particular moment that Stone has captured shows little of the inner workings of either character's mind, but conveys well the upper-middle class milieu in which the pair constantly encounter one another, an ornately furnished drawing-room in the manner of Sixties illustrator and society novelist George Du Maurier:

'You never charge me, Miss Wilfer,' said the Secretary, encountering her by chance alone in the great drawing-room, 'with commissions for home. I shall always be happy to execute any commands you may have in that direction.'

'Pray what may you mean, Mr. Rokesmith?' inquired Miss Bella, with languidly drooping eyelids.

'By home? I mean your father's house Holloway."

She coloured under the retort. . . .

Stone's illustration extends the texts by providing Rokesmith with a pretext for being in the room, namely fetching or returning to their shelves several volumes for the Boffins, and by providing Bella with some theatrical "business," namely reading from an extremely slight but ornately covered volume that may be emblematic of Bella herself, elegantly and fashionably attired and coiffed, but rather shallow in terms of her underlying values.

"You never charge me, Miss Wilfer," said the Secretary, encountering her by chance alone in the great drawing-room, "with commissions for home. I shall always be happy to execute any commands you may have in that direction."

Book 2 Chapter 8

J. Mahoney

Household Edition 1875

Text Illustrated:

"Yet it was not so very long ago that Bella had been fluttered by the discovery that this same Secretary and lodger seem to like her. Ah! but the eminently aristocratic mansion and Mrs. Boffin's dressmaker had not come into play then.

In spite of his seemingly retiring manners a very intrusive person, this Secretary and lodger, in Miss Bella's opinion. Always a light in his office-room when we came home from the play or Opera, and he always at the carriage-door to hand us out. Always a provoking radiance too on Mrs. Boffin's face, and an abominably cheerful reception of him, as if it were possible seriously to approve what the man had in his mind!

"You never charge me, Miss Wilfer," said the Secretary, encountering her by chance alone in the great drawing-room, "with commissions for home. I shall always be happy to execute any commands you may have in that direction."

"Pray what may you mean, Mr?. ? Rokesmith?" inquired Miss Bella, with languidly drooping eyelids.

"By home? I mean your father's house at Holloway."

She coloured under the retort — so skilfully thrust, that the words seemed to be merely a plain answer, given in plain good faith — and said, rather more emphatically and sharply:

"What commissions and commands are you speaking of?"

"Only little words of remembrance as I assume you sent somehow or other," replied the Secretary with his former air. "It would be a pleasure to me if you would make me the bearer of them. As you know, I come and go between the two houses every day."

"You needn't remind me of that, sir."

She was too quick in this petulant sally against "Pa's lodger"; and she felt that she had been so when she met his quiet look."

Commentary:

The lengthy caption and full-page illustration of the Boffins' "great drawing-room" (implying that there is also a "lesser") highlight the Secretary's subtly upbraiding Bella Wilfer for neglecting her John Dickens-like, middle-class family now that she has had the good fortune to be taken up by the wealthy, childless Boffins and has been translated to their suburban mansion, to and from which John Rokesmith travels daily. His subtle goading provokes Bella to visit her parents (in the Boffins' coach, of course) and buy her father a new wardrobe.

This is one of just three full-page illustrations in the 1875 Household Edition volume of Our Mutual Friend, suggesting that Mahoney regarded this scene as highly significant in the plot surrounding the relationship between the Boffins' Secretary, John Rokesmith and the fashionably dressed Bella Wilfer. Mahoney has modeled his illustration in part on the original serial wood-engraving by Marcus Stone, Pa's Lodger and Pa's Daughter (Part 8, December 1864). Sol Eytinge, Jr., depicted a more animated, affectionate Bella and her father together to illustrate the closeness of their relationship, temporarily disrupted by Bella's desire for wealth. The message that Rokesmith conveys to Bella embarrasses her in Mahoney's illustration, as she retreats from engaging with the voice of conscience by thoughtfully examining an exotic houseplant housed on a tripod stand of tropical wood, here a signifier of taste, affluence, and social status, an object equivalent in function to the ornate, High Victorian furnishings in the Stone original, in which Bella pretends to be reading a book and to be disregarding Rokesmith's presence. Clearly his moral intention in the text is to chasten the willful Bella for neglecting her own family, particularly her kindly father, R. W., since the Boffins have elevated her to a loftier socio-economic sphere. If there is a spark in the Stone illustration, it is of suppressed romance and sexuality that one does not find the Mahoney reinterpretation.

John and Bella are surrounded by evidence of wealth and ease, including the many books on the table behind the young man in the great drawing-room. The swirling draperies (right) echo the swirling fabric of Bella's dress, implying that she has become very much a part of this upper-middle-class environment, but also subtly suggesting her agitation at Rokesmith's implied criticism. But the drawing-room furnishings are excessively ornate and massive, although elegant, suggesting the rather cloying nature of this materialistic existence that Bella has so wilfully embraced as the surest route to happiness. John Rokesmith, holding a tome and striking a pose reminiscent of an Old Testament prophet, looks unflinchingly at her, a pillar of moral rectitude, as emphasized by the classical column behind him.

"Now, you may give me a kiss, Pa."

Book 2 Chapter 8

J. Mahoney

Household Edition 1875

Text Illustrated:

"And now, Pa," pursued Bella, "I'll make a confession to you. I am the most mercenary little wretch that ever lived in the world."

"I should hardly have thought it of you, my dear,' returned her father, first glancing at himself; and then at the dessert.

"I understand what you mean, Pa, but it's not that. It's not that I care for money to keep as money, but I do care so much for what it will buy!"

"Really I think most of us do," returned R. W.

"But not to the dreadful extent that I do, Pa. O-o!" cried Bella, screwing the exclamation out of herself with a twist of her dimpled chin. "I am so mercenary!"

"With a wistful glance R. W. said, in default of having anything better to say: "About when did you begin to feel it coming on, my dear?"

"That's it, Pa. That's the terrible part of it. When I was at home, and only knew what it was to be poor, I grumbled but didn't so much mind. When I was at home expecting to be rich, I thought vaguely of all the great things I would do. But when I had been disappointed of my splendid fortune, and came to see it from day to day in other hands, and to have before my eyes what it could really do, then I became the mercenary little wretch I am."

"It's your fancy, my dear."

"I can assure you it's nothing of the sort, Pa!" said Bella, nodding at him, with her very pretty eyebrows raised as high as they would go, and looking comically frightened. "It's a fact. I am always avariciously scheming."

"Lor! But how?"

"I'll tell you, Pa. I don't mind telling you, because we have always been favourites of each other's, and because you are not like a Pa, but more like a sort of a younger brother with a dear venerable chubbiness on him. And besides," added Bella, laughing as she pointed a rallying finger at his face, "because I have got you in my power. This is a secret expedition. If ever you tell of me, I'll tell of you. I'll tell Ma that you dined at Greenwich."

"Well; seriously, my dear," observed R. W., with some trepidation of manner, "it might be as well not to mention it."

"Aha!" laughed Bella. "I knew you wouldn't like it, sir! So you keep my confidence, and I'll keep yours. But betray the lovely woman, and you shall find her a serpent. Now, you may give me a kiss, Pa, and I should like to give your hair a turn, because it has been dreadfully neglected in my absence."

Commentary:

In the early part of this chapter, Rokesmith chides Bella for neglecting her family. To prove the Secretary wrong, Bella takes the Boffins' coach to visit her mother and sisters, who do not respond well to Bella's display of affluence. She then visits her father at work, encouraging him to play hokey that afternoon to join her in a shopping spree — not for herself, but for him. Dressed in the latest fashion, R. W. is then whisked off to Greenwich for a luxurious dinner, at which Bella confesses that she has become mercenary as a result of living with the Boffins. Here, the meal nearly over, the daughter makes this confession to her father, admitting that, now that she has enjoyed a richer lifestyle, she must have a wealthy husband.

There is no immediate Marcus Stone illustration that parallels this Mahoney illustration but Mahoney's illustration is particularly effective in realizing the maritime backdrop, with the two windows of the hotel dining-room offering a panoramic view of ships, spars, and sails, complementing Bella's reference in the text to a ship being towed by a steam-tug. In the interior, a bottle of wine, glasses, flowers, and cruets establish that Bella is treating her father to a splendid dinner. Mahoney establishes continuity by putting her in the same dress that she wore in the previous scene, set in the greater drawing-room of the Boffin mansion, and thereby reminding the viewer of how Rokesmith's subtly delivered criticism has resulted in this act of benevolence. The Cherub, "R. W.," looks much as he does in Mahoney's earlier illustration, When it came Bella's turn to sign her name, Mr. Rokesmith, who was standing, as he had sat, with a hesitating hand upon the table, looked at her stealthily but narrowly Book 1, Chp. 4, providing a built-in reference to her difficult upbringing in Holloway, north London.

Our Johnny

Book 2 Chapter 9

Marcus Stone

Commentary:

Stone's illustration for Book 2, Chapter 9, "In which The Orphan Makes His Will," reminiscent of Phiz's "dark" plates such as those found in Bleak House, is not merely atmospheric in that it complements the text and advances the narrative, for the smokiness and dinginess of the cottage's dark interior foreshadow plot developments with "Our Johnny's" fatal respiratory ailment, likely red measles (or, as Sloppy puts it in describing the formal medical diagnosis, "something as wos wery long for spots"). The reader sees Betty Higden solicitously holding her grandson in her lap (left) as Bella Wilfer peers through the open door (right) and smoke from the fitful fire fills the cavernous fireplace. Stone does not dwell on the quaintness of Betty's scant furniture or bric-a-brac on the mantel, finding little romance in poverty but conveying through the sturdiness and pleasing shape of the chairs Betty's essential dignity. The moment the illustrator has chosen to realize is thus a brief passage in Part 8 (the monthly number for December 1864): “they raised the latch of Betty Higden's door, and saw her sitting in the dimmest and furthest corner with poor Johnny in her lap”. The physical distance between the well-dressed, upper-middle-class visitors at the door and the working class Betty in her chair is a gulf that ultimately consumes the young life upon which the Boffins have laid such hope. When the child they have adopted came down with some childhood ailment caught from "the Minders," Betty had apparently taken the child to the "doctor's shop once", by which we should probably understand the local apothecary's, but, distrustful of institutions, has elected to wait and see whether "Our Johnny would work round", rather than take him to a proper medical establishment:

"To catch up in her arms the sick child who was dear to her, and hide it as if it were a criminal, and keep off all ministration but such as her own ignorant tenderness and patience could supply, had become this woman's idea of maternal love, fidelity, and duty."

Learning of the child's condition from Sloppy, Rokesmith immediately orders the carriage, and within half-an-hour the party are on their way to Brentford. However, once Mrs. Boffin has assessed the child's condition and proposes removing Johnny from the cottage "to where he can be taken better care of", Betty flares up, believing that he is about to be institutionalized.

This, then, is the situation presented in the text. The illustration furnishes the reader with details that Dickens does not: the tidiness and general cleanliness of the cottage, its flagstone floor, and rugged beamed ceiling, its few pieces of solid furniture, and what is possibly the mangle worked by Sloppy to the extreme right. Stone has the light from the single leaded-pane window and the doorway illuminate the diminutive child and Betty's spotlessly clean bonnet, the passage of the light from the doorway drawing our eye left, across the dimly lit, smoky room from Bella towards the grandmother and her charge. The vividly realized — or should we say "improvised"? — details such as the noble basket above Betty's head, on the left-hand side of the mantelpiece, create verisimilitude and subtly convey a sense of the occupant's character.

"A kiss for the Boofer Lady."

Book 2 Chapter 9

J. Mahoney

Household Edition 1875

Text Illustrated:

"So, they kissed him, and left him there, and old Betty was to come back early in the morning, and nobody but Rokesmith knew for certain how that the doctor had said, "This should have been days ago. Too late!"

But, Rokesmith knowing it, and knowing that his bearing it in mind would be acceptable thereafter to that good woman who had been the only light in the childhood of desolate John Harmon dead and gone, resolved that late at night he would go back to the bedside of John Harmon's namesake, and see how it fared with him.

The family whom God had brought together were not all asleep, but were all quiet. From bed to bed, a light womanly tread and a pleasant fresh face passed in the silence of the night. A little head would lift itself up into the softened light here and there, to be kissed as the face went by — for these little patients are very loving — and would then submit itself to be composed to rest again. The mite with the broken leg was restless, and moaned; but after a while turned his face towards Johnny's bed, to fortify himself with a view of the ark, and fell asleep. Over most of the beds, the toys were yet grouped as the children had left them when they last laid themselves down, and, in their innocent grotesqueness and incongruity, they might have stood for the children's dreams.

The doctor came in, too, to see how it fared with Johnny. And he and Rokesmith stood together, looking down with compassion on him.

"What is it, Johnny?" Rokesmith was the questioner, and put an arm round the poor baby as he made a struggle.

"Him!" said the little fellow. "Those!"

The doctor was quick to understand children, and, taking the horse, the ark, the yellow bird, and the man in the Guards, from Johnny's bed, softly placed them on that of his next neighbour, the mite with the broken leg.

With a weary and yet a pleased smile, and with an action as if he stretched his little figure out to rest, the child heaved his body on the sustaining arm, and seeking Rokesmith's face with his lips, said:

"A kiss for the boofer lady."

Having now bequeathed all he had to dispose of, and arranged his affairs in this world, Johnny, thus speaking, left it."

Commentary:

In Chapter 9 of Book Two, when John Rokesmith learns that Johnny, Betty Higden's grandchild, is extremely ill, he, the Boffins, and Bella transport the toddler (once they have won Betty over) to the Sick Children's Hospital — but the attending physician tells the Secretary confidentially that they are too late because the boy's illness is already too far advanced. That evening, as Rokesmith watches over him, the little orphan, last of Betty Higden's line, dies, bequeathing the toys that the doting Boffins have bought him to the child in the next bed. His final sentence involves his giving Rokesmith a kiss that he may implant for Johnny on the lips of Bella Wilfer, the "boofer" lady he saw when the Boffin party arrived at Betty's cottage.

The illustration complements the narration of the death of Johnny, the orphan whom the Boffins have adopted. Again, the focal character here is John Rokesmith. The original serial illustrations included the scene in which Betty Higden is nursing her grandchild in her cottage, "Our Johnny" (Part 8, the monthly number for December 1864), Please, please do NOT read this next sentence if you have not read The Old Curiosity Shop. Tristram, go ahead..... (view spoiler)

As the child endeavors to speak, Rokesmith looks Johnny closely in the face in the Mahoney illustration, but does not put his arm around the child, who is hardly a "baby" and does not appear to "struggle." Already, the horse and ark have been deposited, as requested, on the next bed, and now the physician and nurse look on helplessly. An interesting touch is that Mahoney has made "Johnny" (who was to be called "John Harmon") resemble John Rokesmith in his facial features. Realistic details that suggest Mahoney may have actually studied such a ward in the Sick Children's Hospital of Great Ormond Street, London (much as it would be an anachronism, for the institution opened in the same year as this volume was published, 1875) are the iron-frame beds with side-railings (seen in the April 1858 Illustrated London News illustration A Hospital Ward), the canopy over the neighboring bed, and the nurse's uniform, including the distinctive headgear. In terms of composition, Johnny's head is focal point because it is the corner of a triangle formed by the line of the railing and the physician at the foot of the bed, with the doctor's and Rokesmith's heads drawing the eye of the viewer back to the dying child.

Kim. What delightful illustrations to consider this week. Thank you.

Again, I enjoyed and learned much from the commentaries. The visual representations of the letterpress greatly enhances the reading experience. It is also interesting to note how the illustrators at times depict the same scene, and at other times choose to depict different scenes. It would be interesting to know why this occurred. I also note from the comments that on occasion the illustrators added material to their work that does not appear in the text. This is much like what Hablot Browne did in the later Dickens novels he illustrated. Browne's work complimented and extended both the literal text and added further symbolic meanings to the illustrations. In that way the novel actually had a text and an interpretation of the text rather than a simple reproduction of the words.

We see this complimentary blending of illustrator and text in this week's selections. The pose of Rokesmith, the manner in which he holds the books, the column behind him in Mahoney's Book 2 Chapter 8 illustration all add to the symbolic meaning of the visual illustration.

I would further suggest that the Book 2 Chapter 8 Marcus Stone illustration interprets the scene as much as depicts it. In the left middle edge of the illustration we have the depiction of a man under glass. While the Victorians often kept a clock under glass on a table or mantle here we have a human. Above that display on the table stands Rokesmith. Both Rokesmith and the figure under glass are looking at Bella, whose back is turned away from them. To me, this symbolizes how Rokesmith is being held away from Bella, shut off from her now he is a mere clerk while she has risen in the social world. I found the comparison of Bella to Estella in GE to be very insightful.

If we look at the mantle on the right hand of the illustration we see a what appears to be a display of peacock feathers. How appropriate that Bella is looking at a book and facing the feathers. Peacock feathers were a symbol of vanity and the book is an ornament for Bella. I seriously doubt if a book would be an item Bella spends time contemplating. It does, however, present the image of an intellectual position since the book is ornate and definitely not a yellow-back.

Again, I enjoyed and learned much from the commentaries. The visual representations of the letterpress greatly enhances the reading experience. It is also interesting to note how the illustrators at times depict the same scene, and at other times choose to depict different scenes. It would be interesting to know why this occurred. I also note from the comments that on occasion the illustrators added material to their work that does not appear in the text. This is much like what Hablot Browne did in the later Dickens novels he illustrated. Browne's work complimented and extended both the literal text and added further symbolic meanings to the illustrations. In that way the novel actually had a text and an interpretation of the text rather than a simple reproduction of the words.

We see this complimentary blending of illustrator and text in this week's selections. The pose of Rokesmith, the manner in which he holds the books, the column behind him in Mahoney's Book 2 Chapter 8 illustration all add to the symbolic meaning of the visual illustration.

I would further suggest that the Book 2 Chapter 8 Marcus Stone illustration interprets the scene as much as depicts it. In the left middle edge of the illustration we have the depiction of a man under glass. While the Victorians often kept a clock under glass on a table or mantle here we have a human. Above that display on the table stands Rokesmith. Both Rokesmith and the figure under glass are looking at Bella, whose back is turned away from them. To me, this symbolizes how Rokesmith is being held away from Bella, shut off from her now he is a mere clerk while she has risen in the social world. I found the comparison of Bella to Estella in GE to be very insightful.

If we look at the mantle on the right hand of the illustration we see a what appears to be a display of peacock feathers. How appropriate that Bella is looking at a book and facing the feathers. Peacock feathers were a symbol of vanity and the book is an ornament for Bella. I seriously doubt if a book would be an item Bella spends time contemplating. It does, however, present the image of an intellectual position since the book is ornate and definitely not a yellow-back.

Kim wrote: "Chapter 9 is titled, "In Which The Orphan Makes His Will", which I suppose is a fine name for a chapter that goes along like this one goes along. This is the chapter Tristram was so delighted to fi..."

Well Kim, this was a hard chapter to take. I'm wondering how we could approach the title. Here we have the second will of the novel. The Harmon will was one of great wealth, and we have seen in the novel how this wealth has altered the lives of many of the novel's central characters. Indeed, the preceding chapter has shown us Bella in a self-confession admitting how mercenary she is.

Now we have the death of a second person who is definitely not wealthy. Why has Dickens juxtaposed these two chapters? I would suggest it is, at least partially, to show how the poor can be more generous that the rich. Johnny "bequeathed all he had to dispose of" and then he passes. Johnny gives his wealth, such as it is, without qualification, without stipulation and without hesitation. His is an act of love and gratitude for what he had.

Johnny reminds me somewhat of Jo from BH. He too understood loyalty and kindness. How can we forget how he swept the gate of the graveyard where Nemo was buried? Here, in OMF, Johnny fulfills the same role as he reminds the reader of two central facts. The first is that the poor suffer far too much and without not nearly enough attention from the rich. Second, many poor have a quiet and profound dignity that goes apparently unacknowledged and unappreciated.

Compare as well how Rokesmith - like Esther who did not shun Jo in BH - embraces Johnny by " putting an arm around the poor baby as he made his struggles." There are three items Johnny bequeathed: a horse; an ark; and a yellow bird. Why were these the items that were selected? I would suggest that the ark is a symbol of what was saved for a future world by Noah. Dickens asks us to consider the extent people are willing to save society. The yellow bird is a symbol of hope and freedom. Yellow is the colour of gold, of wealth. Will society release its wealth for all to share? The horse. Well, I would suggest that it is an apocalyptic horse. Death, disease, famine and war could also be unleashed if society does not pay more attention to its most needy. I do not consider this too far-fetched. The first working idea for A Christmas Carol was tentatively called "A Sledge Hammer." Dickens wanted no mistaking his message in ACC.

Finally, notice that it is Rokesmith who is the witness to both the events of chapter 8 with its theme of wealth and mercenary ways and the deathbed kindness of Johnny. I do not think this was done by chance.

Well Kim, this was a hard chapter to take. I'm wondering how we could approach the title. Here we have the second will of the novel. The Harmon will was one of great wealth, and we have seen in the novel how this wealth has altered the lives of many of the novel's central characters. Indeed, the preceding chapter has shown us Bella in a self-confession admitting how mercenary she is.

Now we have the death of a second person who is definitely not wealthy. Why has Dickens juxtaposed these two chapters? I would suggest it is, at least partially, to show how the poor can be more generous that the rich. Johnny "bequeathed all he had to dispose of" and then he passes. Johnny gives his wealth, such as it is, without qualification, without stipulation and without hesitation. His is an act of love and gratitude for what he had.

Johnny reminds me somewhat of Jo from BH. He too understood loyalty and kindness. How can we forget how he swept the gate of the graveyard where Nemo was buried? Here, in OMF, Johnny fulfills the same role as he reminds the reader of two central facts. The first is that the poor suffer far too much and without not nearly enough attention from the rich. Second, many poor have a quiet and profound dignity that goes apparently unacknowledged and unappreciated.

Compare as well how Rokesmith - like Esther who did not shun Jo in BH - embraces Johnny by " putting an arm around the poor baby as he made his struggles." There are three items Johnny bequeathed: a horse; an ark; and a yellow bird. Why were these the items that were selected? I would suggest that the ark is a symbol of what was saved for a future world by Noah. Dickens asks us to consider the extent people are willing to save society. The yellow bird is a symbol of hope and freedom. Yellow is the colour of gold, of wealth. Will society release its wealth for all to share? The horse. Well, I would suggest that it is an apocalyptic horse. Death, disease, famine and war could also be unleashed if society does not pay more attention to its most needy. I do not consider this too far-fetched. The first working idea for A Christmas Carol was tentatively called "A Sledge Hammer." Dickens wanted no mistaking his message in ACC.

Finally, notice that it is Rokesmith who is the witness to both the events of chapter 8 with its theme of wealth and mercenary ways and the deathbed kindness of Johnny. I do not think this was done by chance.

Kim wrote: ""A kiss for the Boofer Lady."

Book 2 Chapter 9

J. Mahoney

Household Edition 1875

Text Illustrated:

"So, they kissed him, and left him there, and old Betty was to come back early in the morning..."

There are many ways to interpret this death-bed scene. To me, perhaps it is because of the coming Diana retrospective, I think of Lady Diana kissing the AID's babies. An act that was, for then and even perhaps now, incredibly brave and selfless.

Book 2 Chapter 9

J. Mahoney

Household Edition 1875

Text Illustrated:

"So, they kissed him, and left him there, and old Betty was to come back early in the morning..."

There are many ways to interpret this death-bed scene. To me, perhaps it is because of the coming Diana retrospective, I think of Lady Diana kissing the AID's babies. An act that was, for then and even perhaps now, incredibly brave and selfless.

Peter,

I really enjoyed reading your interpretations of the illustrations and of the orphan's will! Personally, I did not really like this week's range of chapters, with the exception of the Wegg-Venus tryst because that one was really funny.

I like Bella less and less, and my dislike also spreads to her father now: The idea of how this young woman twirls the hair of her father, getting it into a dishevelled state - just like Twemlow and his egg application - and how the grown-up man allows himself to be made a ridiculous figure with his hair standing on end, all this is getting on my nerves. And then, how Bella said that she does not regard her father so much as a father but more as a younger brother - it was also annoying to me as I found it so silly.

Nevertheless, the chapter showed two things about Bella to me: Number one, even in her daydreams about her own and her father's happy future, money plays a very big role to her, and so I guess she is right when she says that she is mercenary. Saying this, however, I'd add that there is some common sense in being a bit mercenary, not too much, but a bit - because you cannot live on dreams alone but have to consider realities. And for a young woman it Bella's position, it would certainly have been unwise to marry a man whose monetary prospects are, at best, dim. After all, she has the example of her parents' marriage before her eyes, a marriage that is anything but happy, and I am sure that poverty also played a role when it came to souring the disposition of Mrs. Wilfer - the Funeral March from Saul! Therefore, it is very wise in Bella not to disregard money in a romantic whim.

Number Two, she does care about Rokesmith after all, for is it not due to his admonition that she paid a visit to her family. One can say that Rokesmith brings out the better person in her.

I really enjoyed reading your interpretations of the illustrations and of the orphan's will! Personally, I did not really like this week's range of chapters, with the exception of the Wegg-Venus tryst because that one was really funny.

I like Bella less and less, and my dislike also spreads to her father now: The idea of how this young woman twirls the hair of her father, getting it into a dishevelled state - just like Twemlow and his egg application - and how the grown-up man allows himself to be made a ridiculous figure with his hair standing on end, all this is getting on my nerves. And then, how Bella said that she does not regard her father so much as a father but more as a younger brother - it was also annoying to me as I found it so silly.