The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Our Mutual Friend

Our Mutual Friend

>

OMF, Book 2, Chp. 04-06

Chapter 5 closely belongs to the preceding Chapter, as can be seen already from the title “Mercury Prompting.” Whereas Cupid was the Roman God of Love, Mercury was, among other things, the Patron of Trade – but also of Thieves, these latter two often going together. We get quite a different view on Fledgeby at the very beginning of the chapter:

One can even say that Fledgeby’s very existence is the result of some kind of horse-trade [1] because his father was a very rich moneylender, and his mother one of his debtors. The mother, being unable to pay back her debts, solved the problem by marrying the man to whom she owed them. Poor Fledgeby! because a marriage started like that can hardly be a happy one, and the narrator leaves no doubt that it wasn’t. The chapter introduces us to a breakfast Fledgeby and Mr Lammle “enjoy” the next morning in Fledgeby’s apartment, and we soon learn what a cheeseparing, niggard, closefisted man this Fledgeby is, even in such everyday things like a breakfast.

Neither does Fledgeby want to commit himself in any way to Lammle, and so he does not make any comment on Georgiana and on the previous evening but even deals in a rather impertinent and high-handed way with Lammle, who – surprise, surprise – owns him some money. In a way, the pattern that led to the marriage of Fledgeby’s parents seems to be repeated here: Lammle wants to match Georgiana and Fledgeby in order to get rid of his debts with Fledgeby, but this young man is so mean as to not give his conspirator any sign that the deal is accepted. It is only when Lammle starts bullying Fledgeby that the young man shows some subservience. So, their breakfast does end in a sort of mutual understanding after all.

After his breakfast, Fledgeby makes a visit at a shop with the inscription “Pubsey and Co”, which is run by a Jew called Riah. It soon becomes clear that it is actually Fledgeby who runs the shop and who uses Riah – a man who stands indebted to Fledgeby but who does not share any of the young man’s vices – as a kind of straw-man to extort more money from his victims. Riah not only sells second-hand stuff but also acts as a money-lender. So whenever Riah has to tell a customer that he cannot grant him lower interest or more time to pay back his debts without asking his master first, the applicant in question will always come to the conclusion that this is just some sort of prevarication on Mr Riah’s part.

It would be interesting to discuss the question whether the introduction of Riah into the story and the way he is described is not some sort of belated amends on Dickens’s part for having used anti-Semitic stereotypes in his creation of Fagin.

When Fledgeby pays his visit to Riah in order to see whether the shop is run according to his ideas, he learns that Riah has visitors and is curious to see who they are. He is led up onto the roof of the house – here Mr Riah has actually created a small garden –, where we see Lizzie and Jenny Wren. The latter usually buys old rags in the shop in order to make her dolls’ dresses with them, whereas Lizzie seems to go to Riah’s in order to be taught how to read and write. Fledgeby is not overly impressed with these two guests and first of all checks whether Jenny has been made to pay a good price for her goods.

There is some very disturbing and eerie scene, which I will quote without a comment:

[1] I looked that one up. In German we say Kuhhandel (i.e. cow deal) when we want to refer to a dubious bargain, and this is what I meant here.

”He was the meanest cur existing, with a single pair of legs. And instinct (a word we all clearly understand) going largely on four legs, and reason always on two, meanness on four legs never attains the perfection of meanness on two.”

One can even say that Fledgeby’s very existence is the result of some kind of horse-trade [1] because his father was a very rich moneylender, and his mother one of his debtors. The mother, being unable to pay back her debts, solved the problem by marrying the man to whom she owed them. Poor Fledgeby! because a marriage started like that can hardly be a happy one, and the narrator leaves no doubt that it wasn’t. The chapter introduces us to a breakfast Fledgeby and Mr Lammle “enjoy” the next morning in Fledgeby’s apartment, and we soon learn what a cheeseparing, niggard, closefisted man this Fledgeby is, even in such everyday things like a breakfast.

Neither does Fledgeby want to commit himself in any way to Lammle, and so he does not make any comment on Georgiana and on the previous evening but even deals in a rather impertinent and high-handed way with Lammle, who – surprise, surprise – owns him some money. In a way, the pattern that led to the marriage of Fledgeby’s parents seems to be repeated here: Lammle wants to match Georgiana and Fledgeby in order to get rid of his debts with Fledgeby, but this young man is so mean as to not give his conspirator any sign that the deal is accepted. It is only when Lammle starts bullying Fledgeby that the young man shows some subservience. So, their breakfast does end in a sort of mutual understanding after all.

After his breakfast, Fledgeby makes a visit at a shop with the inscription “Pubsey and Co”, which is run by a Jew called Riah. It soon becomes clear that it is actually Fledgeby who runs the shop and who uses Riah – a man who stands indebted to Fledgeby but who does not share any of the young man’s vices – as a kind of straw-man to extort more money from his victims. Riah not only sells second-hand stuff but also acts as a money-lender. So whenever Riah has to tell a customer that he cannot grant him lower interest or more time to pay back his debts without asking his master first, the applicant in question will always come to the conclusion that this is just some sort of prevarication on Mr Riah’s part.

It would be interesting to discuss the question whether the introduction of Riah into the story and the way he is described is not some sort of belated amends on Dickens’s part for having used anti-Semitic stereotypes in his creation of Fagin.

When Fledgeby pays his visit to Riah in order to see whether the shop is run according to his ideas, he learns that Riah has visitors and is curious to see who they are. He is led up onto the roof of the house – here Mr Riah has actually created a small garden –, where we see Lizzie and Jenny Wren. The latter usually buys old rags in the shop in order to make her dolls’ dresses with them, whereas Lizzie seems to go to Riah’s in order to be taught how to read and write. Fledgeby is not overly impressed with these two guests and first of all checks whether Jenny has been made to pay a good price for her goods.

There is some very disturbing and eerie scene, which I will quote without a comment:

”‘The quiet!’ repeated Fledgeby, with a contemptuous turn of his head towards the City’s roar. ‘And the air!’ with a ‘Poof!’ at the smoke.

‘Ah!’ said Jenny. ‘But it’s so high. And you see the clouds rushing on above the narrow streets, not minding them, and you see the golden arrows pointing at the mountains in the sky from which the wind comes, and you feel as if you were dead.’

The little creature looked above her, holding up her slight transparent hand.

‘How do you feel when you are dead?’ asked Fledgeby, much perplexed.

‘Oh, so tranquil!’ cried the little creature, smiling. ‘Oh, so peaceful and so thankful! And you hear the people who are alive, crying, and working, and calling to one another down in the close dark streets, and you seem to pity them so! And such a chain has fallen from you, and such a strange good sorrowful happiness comes upon you!’

Her eyes fell on the old man, who, with his hands folded, quietly looked on.

‘Why it was only just now,’ said the little creature, pointing at him, ‘that I fancied I saw him come out of his grave! He toiled out at that low door so bent and worn, and then he took his breath and stood upright, and looked all round him at the sky, and the wind blew upon him, and his life down in the dark was over!—Till he was called back to life,’ she added, looking round at Fledgeby with that lower look of sharpness. ‘Why did you call him back?’

‘He was long enough coming, anyhow,’ grumbled Fledgeby.

‘But you are not dead, you know,’ said Jenny Wren. ‘Get down to life!’

Mr Fledgeby seemed to think it rather a good suggestion, and with a nod turned round. As Riah followed to attend him down the stairs, the little creature called out to the Jew in a silvery tone, ‘Don’t be long gone. Come back, and be dead!’ And still as they went down they heard the little sweet voice, more and more faintly, half calling and half singing, ‘Come back and be dead, Come back and be dead!’”

[1] I looked that one up. In German we say Kuhhandel (i.e. cow deal) when we want to refer to a dubious bargain, and this is what I meant here.

Chapter 6 takes up some other characters but is also, indirectly, connected with what we have seen in the last chapter. It also proclaims to give us “A Riddle Without an Answer”. It brings us back to Mortimer and Eugene, which some of us might like, others not – I’d have preferred a visit at Mr Wegg’s. The two young men are as listless as ever but lately, Eugene has made some efforts of giving their lodgings a more homely and settled state, even providing a kitchen they will probably never use. A jarring moment occurs to me when Eugene professes that he means to pay their craftsmen and retailers; in other words, what they have got is not paid for and probably some decent people and their families are now waiting for money to come from those two feckless lawyers.

It also becomes clear that Mortimer has noticed some changes in Eugene, and that he suspects his friend of holding back with something – e.g. during the trip they took, Eugene repeatedly absented himself for some time, and Mortimer has no idea where Eugene actually went, and neither has Eugene an idea of telling him. We also get a little glimpse into the history of the friendship of the two men, which also tells us something about the informal hierarchy between them:

So, if Mortimer imitates Eugene, is that the reason why he has adopted the devil-may-care attitude that also did not go down too well with Mr Boffin, and why he does not go about his business in a more enterprising and determined fashion? Is Eugene, like Steerforth, one of those friends one would better be off without? Eugene describes himself as “an embodied conundrum” which he, himself has long given up figuring out.

Their conversation is interrupted by the arrival of two visitors, a boy and a man, in whom Eugene languidly recognizes Charley Hexam and his friend Bradley Headstone. What now follows is an intriguing conversation in which it becomes clear that Eugene and Headstone are at daggers drawn with each other, and that the reason is Lizzie. The starting point of the conversation is Charley’s desire to tell Eugene that he himself wanted to provide a teacher for his sister and that this teacher would have been Mr Headstone. He regards it as an unwanted interference into their own affairs that Eugene has stepped in and employed another teacher, all the more so since his sister finally accepted Eugene’s offer whereas she could not be brought around to accept the earlier offer coming from Charley. Charley also tells Eugene that it will not do for him to be hovering around his sister all the time, not the least because this will also cast a bad light on him, Charley, who has done everything in life to raise himself up and to open some prospects in front of himself – very selfish motives, all in all. Interestingly, during the whole conversation, neither Eugene nor Bradley is paying any attention to the boy.

It is actually quite painful to witness how expertly Eugene humiliates Bradley repeatedly in the course of their conversation, and how blindly the teacher, fuelled by his passion, not only runs into these traps but sets up some of them himself. Their psycho-duel culminates when Charley has had his say – with the typical

and leaves the room, waiting downstairs for Mr Headstone. Headstone wants to impress Eugene by saying that Charley might be a boy but that he, Headstone, will stand by him. Nevertheless, the lawyer is not in the least intimidated but continues his dismissive, humiliating behaviour. This bit here might be interesting in the light of possible further events:

Maybe, Eugene, unwittingly, has hit upon something in Bradley’s character here. It is probably a moot point which one of the two men is the least likeable, but we’ll see, but Bradley might not be so wrong after all when he says,

When Headstone has finally left, Mortimer tells Eugene that now he sees clear as to what was behind Eugene’s strange behaviour and he wishes to know what Eugene intentions are. His friend tells him that “[t]here is no better girl in all this London than Lizzie Hexam” but that he is not intending to marry her. Upon the question where he designs to pursue her, he evadingly answers that he is not capable of any designs.

I think we finally have something like a plot here.

It also becomes clear that Mortimer has noticed some changes in Eugene, and that he suspects his friend of holding back with something – e.g. during the trip they took, Eugene repeatedly absented himself for some time, and Mortimer has no idea where Eugene actually went, and neither has Eugene an idea of telling him. We also get a little glimpse into the history of the friendship of the two men, which also tells us something about the informal hierarchy between them:

”Despite that pernicious assumption of lassitude and indifference, which had become his second nature, he was strongly attached to his friend. He had founded himself upon Eugene when they were yet boys at school; and at this hour imitated him no less, admired him no less, loved him no less than in those departed days.”

So, if Mortimer imitates Eugene, is that the reason why he has adopted the devil-may-care attitude that also did not go down too well with Mr Boffin, and why he does not go about his business in a more enterprising and determined fashion? Is Eugene, like Steerforth, one of those friends one would better be off without? Eugene describes himself as “an embodied conundrum” which he, himself has long given up figuring out.

Their conversation is interrupted by the arrival of two visitors, a boy and a man, in whom Eugene languidly recognizes Charley Hexam and his friend Bradley Headstone. What now follows is an intriguing conversation in which it becomes clear that Eugene and Headstone are at daggers drawn with each other, and that the reason is Lizzie. The starting point of the conversation is Charley’s desire to tell Eugene that he himself wanted to provide a teacher for his sister and that this teacher would have been Mr Headstone. He regards it as an unwanted interference into their own affairs that Eugene has stepped in and employed another teacher, all the more so since his sister finally accepted Eugene’s offer whereas she could not be brought around to accept the earlier offer coming from Charley. Charley also tells Eugene that it will not do for him to be hovering around his sister all the time, not the least because this will also cast a bad light on him, Charley, who has done everything in life to raise himself up and to open some prospects in front of himself – very selfish motives, all in all. Interestingly, during the whole conversation, neither Eugene nor Bradley is paying any attention to the boy.

”Composedly smoking, he [i.e. Eugene] leaned an elbow on the chimneypiece, at the side of the fire, and looked at the schoolmaster. It was a cruel look, in its cold disdain of him, as a creature of no worth. The schoolmaster looked at him, and that, too, was a cruel look, though of the different kind, that it had a raging jealousy and fiery wrath in it.”

It is actually quite painful to witness how expertly Eugene humiliates Bradley repeatedly in the course of their conversation, and how blindly the teacher, fuelled by his passion, not only runs into these traps but sets up some of them himself. Their psycho-duel culminates when Charley has had his say – with the typical

”’[…] Now I don’t choose her to be grateful to him, or to be grateful to anybody but me, except Mr. Headstone. […]’” –

and leaves the room, waiting downstairs for Mr Headstone. Headstone wants to impress Eugene by saying that Charley might be a boy but that he, Headstone, will stand by him. Nevertheless, the lawyer is not in the least intimidated but continues his dismissive, humiliating behaviour. This bit here might be interesting in the light of possible further events:

”‘Mr Wrayburn, at least I know very well that it would be idle to set myself against you in insolent words or overbearing manners. That lad who has just gone out could put you to shame in half-a-dozen branches of knowledge in half an hour, but you can throw him aside like an inferior. You can do as much by me, I have no doubt, beforehand. […] Do you suppose that a man, in forming himself for the duties I discharge, and in watching and repressing himself daily to discharge them well, dismisses a man’s nature?’

‘I suppose you,’ said Eugene, ‘judging from what I see as I look at you, to be rather too passionate for a good schoolmaster.’ As he spoke, he tossed away the end of his cigar.

‘Passionate with you, sir, I admit I am. Passionate with you, sir, I respect myself for being. But I have not Devils for my pupils.’

‘For your Teachers, I should rather say,’ replied Eugene.”

Maybe, Eugene, unwittingly, has hit upon something in Bradley’s character here. It is probably a moot point which one of the two men is the least likeable, but we’ll see, but Bradley might not be so wrong after all when he says,

”‘You reproach me with my origin, […] you cast insinuations at my bringing-up. But I tell you, sir, I have worked my way onward, out of both and in spite of both, and have a right to be considered a better man than you, with better reasons for being proud.’”

When Headstone has finally left, Mortimer tells Eugene that now he sees clear as to what was behind Eugene’s strange behaviour and he wishes to know what Eugene intentions are. His friend tells him that “[t]here is no better girl in all this London than Lizzie Hexam” but that he is not intending to marry her. Upon the question where he designs to pursue her, he evadingly answers that he is not capable of any designs.

I think we finally have something like a plot here.

Tristram wrote: "Dear Curiosities,

In this week’s three chapters, we seem to be finally getting some information as to plot development, but still Dickens feels that he has not enough characters as yet for he thro..."

Tristram

Thank you for such a detailed outline of the chapter. I especially enjoyed your phrase "but we better not jump to conclusions." Truer words have never been said about the style of Dickens.

The discussion between Mrs Lammle and Georgiana was worrisome. It felt like Mrs Lammle was the spider and Georgiana a very helpless fly. The Lammles are a very nasty pair. There was such deep irony and satire in the discussion of the love between the Lammles. When Mrs Lammle comments " I believe that he loves me as much as I love him" I cringed. OMF is presenting us with many variations on the theme of love.

I am very happy to see that more bird references are flocking into the novel. Fledgeby is quite the character. The word "fledge" of course refers to a bird that is ready to leave the nest. By the end of this week's chapters we learn that Fledgeby has a fine set of claws on him. He appears to be another bird of prey. Upon whom will he attempt to feast?

As Tristram noted, there is a lingering violence with the action of violence with a soda bottle, and the mention of "wringing the neck of some unlucky creature pouring its blood down his throat." Nasty times ahead?

In this week’s three chapters, we seem to be finally getting some information as to plot development, but still Dickens feels that he has not enough characters as yet for he thro..."

Tristram

Thank you for such a detailed outline of the chapter. I especially enjoyed your phrase "but we better not jump to conclusions." Truer words have never been said about the style of Dickens.

The discussion between Mrs Lammle and Georgiana was worrisome. It felt like Mrs Lammle was the spider and Georgiana a very helpless fly. The Lammles are a very nasty pair. There was such deep irony and satire in the discussion of the love between the Lammles. When Mrs Lammle comments " I believe that he loves me as much as I love him" I cringed. OMF is presenting us with many variations on the theme of love.

I am very happy to see that more bird references are flocking into the novel. Fledgeby is quite the character. The word "fledge" of course refers to a bird that is ready to leave the nest. By the end of this week's chapters we learn that Fledgeby has a fine set of claws on him. He appears to be another bird of prey. Upon whom will he attempt to feast?

As Tristram noted, there is a lingering violence with the action of violence with a soda bottle, and the mention of "wringing the neck of some unlucky creature pouring its blood down his throat." Nasty times ahead?

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 5 closely belongs to the preceding Chapter, as can be seen already from the title “Mercury Prompting.” Whereas Cupid was the Roman God of Love, Mercury was, among other things, the Patron o..."

Chapter 5 is yet another chapter that offers a rich vignette, one that does tie in with the apparent central thrusts of the novel. I am beginning to feel what the central focuses and tropes of the novel are. Money to be sure, relationships, honesty and personal initiatives, or the lack of the same, and trust. A rather lengthy list.

In terms of symbolism it was interesting to find a garden on top of the building. It is an oasis in the midst of the squalor of London, the political and social manoeuvrings in London drawing rooms, and the deaths on the Thames. To date, I cannot recall much that was green, natural or healthy in the novel. Interesting to note that in such a place we find people who are engaged in honest industry, in the case of Jenny, and getting an education in the case of Lizzie. Is it a coincidence that they are both young and both female? I think not. As to Tristram's question regarding Dickens's portrayal of Riah, I do think we see Dickens softening his earlier portrayals of the Jewish race.

I wonder if Fledgeby's warning to Lammle not to think he was a "doll and puppet" bears any connection to Jenny Wren and her making of dolls? Interesting to note that a few paragraphs later Fledgeby again warns Lammle not to see him as a puppet.

As an anecdotal aside, I was, of course, glad to note that Lemmle and Fledgeby were eating eggs. While I realize millions of Londoners probably ate an egg for breakfast that fictitious day, an egg is an unformed bird. Will Lemmle/Fledgeby hatch any future plans? I couldn't resist the bad pun. :-))

Chapter 5 is yet another chapter that offers a rich vignette, one that does tie in with the apparent central thrusts of the novel. I am beginning to feel what the central focuses and tropes of the novel are. Money to be sure, relationships, honesty and personal initiatives, or the lack of the same, and trust. A rather lengthy list.

In terms of symbolism it was interesting to find a garden on top of the building. It is an oasis in the midst of the squalor of London, the political and social manoeuvrings in London drawing rooms, and the deaths on the Thames. To date, I cannot recall much that was green, natural or healthy in the novel. Interesting to note that in such a place we find people who are engaged in honest industry, in the case of Jenny, and getting an education in the case of Lizzie. Is it a coincidence that they are both young and both female? I think not. As to Tristram's question regarding Dickens's portrayal of Riah, I do think we see Dickens softening his earlier portrayals of the Jewish race.

I wonder if Fledgeby's warning to Lammle not to think he was a "doll and puppet" bears any connection to Jenny Wren and her making of dolls? Interesting to note that a few paragraphs later Fledgeby again warns Lammle not to see him as a puppet.

As an anecdotal aside, I was, of course, glad to note that Lemmle and Fledgeby were eating eggs. While I realize millions of Londoners probably ate an egg for breakfast that fictitious day, an egg is an unformed bird. Will Lemmle/Fledgeby hatch any future plans? I couldn't resist the bad pun. :-))

Since Dickens has been playing with riddles and nursery rhymes, I am emboldened to play at making paper chains, specifically chains of characters.

Since Dickens has been playing with riddles and nursery rhymes, I am emboldened to play at making paper chains, specifically chains of characters.Chain the first:

Tremlow is linked to the Veneerings who are linked to the Podsnaps who are linked to the Lammles who are linked to Fledgeby who is linked to Riah who is linked to Jenny Wren who is linked to Lizzie who is linked to Wrayburn.

Chain the second:

Venus is linked to Wegg who is linked to the Boffins who are linked to the Wilfers who are linked to Rokesmith who is mysteriously linked to Lightwood.

Both Wrayburn and Lightwood are NOW linked to Headstone and Charley, and are earlier linked to Hexam and Riderhood.

Also of note, both Tremlow and Fledgeby are relations of the Snigsworth line.

LindaH wrote: "Since Dickens has been playing with riddles and nursery rhymes, I am emboldened to play at making paper chains, specifically chains of characters.

Chain the first:

Tremlow is linked to the Veneer..."

Ah, Linda

Do you live at 221B Baker Street by any chance?

There is a song that has the line "chain, chain, chain, chain of fools." In your case, we have something much better. We now have a chain of possibilities and, dare I say, probabilities?

Well done.

Chain the first:

Tremlow is linked to the Veneer..."

Ah, Linda

Do you live at 221B Baker Street by any chance?

There is a song that has the line "chain, chain, chain, chain of fools." In your case, we have something much better. We now have a chain of possibilities and, dare I say, probabilities?

Well done.

"Mr. and Mrs. Alfred Lammle"

Book 2 Chapter 4

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

1870

Commentary:

Dickens's connecting Alfred Lammle and "Fascination" Fledgeby with the fashionable bachelor apartments at The Albany, near Piccadilly Circus, to the modern reader would suggest an intertextual relationship between Oscar Wilde's society farce The Importance of Being Earnest (1895) and Dickens's assault on the mercenary nature of mid-Victorian society in Our Mutual Friend (1864-65). However, Alfred and Sophronia Lammle, depicted by Marcus Stone on the beach on their Isle of Wight honeymoon in "The Happy Pair" (sixth illustration) and by Sol Eytinge in his tenth illustration set some time later in the couple's Piccadilly parlour, are far less benign than the somewhat vacuous ingenues of Wilde's play thirty years later. By the time that we encounter them in the Ticknor Fields 1870 edition of the novel, we are quite aware of the Lammles' plans to gull the discontented heiress and daughter of a marine insurance broker, Georgiana Podsnap, in a scheme involving marrying her to the ridiculous Fledgeby.

Despite the respectability of their Sackville Street parlour and correctness of their breakfast table, through their poses and sharp features illustrator Sol Eytinge reveals the couple's predatory natures. As Dickens's text implies, the pair are hatching a scheme intent upon separating the wealthy Podsnap from some of his fortune by arranging a surreptitious marriage for his daughter. In the illustration for Book 2, Chapter 4, "Cupid Prompted," Eytinge implies the Lammles' being experts at sharp practice by the pointed nose (Dickens specifies he has "too much nose"), sharp fingers, and demonic grin of the husband, and the casual self-assurance of the wife, who even in private demonstrates the acute fashion sense that has rendered her a "consciously 'splendid woman'" in the Veneerings' social set. Eytinge suggests their Piccadilly townhouse's "handsome fittings and furnishings" through the tables and paintings, although he does not include the mirror which reflects Sophronia Lammle's smirking expression as she deprecates Miss Podsnap just after the young lady has left the room.

Nothing more was said between the happy pair. Perhaps conspirators who have once established an understanding, may not be over fond of repeating the terms and objects of their conspiracy.

Eytinge's depiction of the fortune-hunting Lammles is consistent with Marcus Stone's sixth illustration, "The Happy Pair," which shows the couple on their honeymoon at Shanklin on the Isle of Wight, then a fashionable vacation-spot. In Stone's earlier illustration for Book 1, Chapter 10, "A Marriage Contract," however, the husband and wife are in a "moody humour" because each has married the other for "property" and has just realized that the partner has none. At the conclusion of that scene the pair resolve to work together to deceive others in "Any scheme that will bring [them] money." In Stone's illustration, ironically entitled "The Happy Pair," only Alfred Lammle is of a decidedly Mephistophelean character. In contrast, Eytinge more accurately conveys a sense of their devious natures through delineating their facial features while Stone concentrates on showing their listless postures, fashionable dress, and Alfred Lammle's luxuriant, "gingerous whiskers".

Since Eytinge specifically sets his scene at a breakfast table, he is probably conflating the earlier scene, immediately after Miss Podsnap's departure, with a later scene, in which Alfred is "Fascination" Fledgeby's guest at breakfast in his chambers at The Albany in Book 2, Chapter 5, "Mercury Prompting." The scene between the mercenary husband and wife in the previous chapter is probably later in the day; Dickens mentions no meal in connection with the visitor just departed, and the fashionable Lammles would not likely have such a visitor at breakfast. The artist, however, may have conceived of Lammles as sychophantal lay-abouts, and chosen to imply that they rise late as Alfred is an "adventurer" of no particular occupation. At Fledgeby's,

"Alfred Lammle pushed his plate away (no great sacrifice under the circumstances of there being so little in it), thrust his hands in his pockets, leaned back in his chair, and contemplated Fledgeby in silence."

Lammle in Eytinge's plate is animatedly conversing with his wife, seated in throne-like repose; she regards him and his marital scheme somewhat skeptically, if one may judge by her expression. We can well imagine Alfred's saying that Fledgeby in matters involving money is "a match for the Devil," and Sophronia's riposting, "Is he a match for you?"

"Ah! Here was Alfred. Having stolen in unobserved, he playfully leaned on the back of Sophronia's chair."

Book 2 Chapter 4

J. Mahoney

Household Edition 1875

Text Illustrated:

"Sophronia's glance was as if a rather new light broke in upon her. It shaded off into a cool smile, as she said, with her eyes upon her lunch, and her eyebrows raised:

"You are quite wrong, my love, in your guess at my meaning. What I insinuated was, that my Georgiana's little heart was growing conscious of a vacancy."

"No, no, no," said Georgiana. "I wouldn't have anybody say anything to me in that way for I don't know how many thousand pounds."

"In what way, my Georgiana?" inquired Mrs. Lammle, still smiling coolly with her eyes upon her lunch, and her eyebrows raised.

"You know," returned poor little Miss Podsnap. "I think I should go out of my mind, Sophronia, with vexation and shyness and detestation, if anybody did. It's enough for me to see how loving you and your husband are. That's a different thing. I couldn't bear to have anything of that sort going on with myself. I should beg and pray to — to have the person taken away and trampled upon."

Ah! here was Alfred. Having stolen in unobserved, he playfully leaned on the back of Sophronia's chair, and, as Miss Podsnap saw him, put one of Sophronia's wandering locks to his lips, and waved a kiss from it towards Miss Podsnap.

"What is this about husbands and detestations?" inquired the captivating Alfred.

"Why, they say," returned his wife, "that listeners never hear any good of themselves; though you — but pray how long have you been here, sir?"

"This instant arrived, my own."

Commentary:

Alfred Lammle, confidence man, has not merely resigned himself to the fact that his new wife, Sophronia, is up to the same game; rather, he has joined forces with her in a scheme to profit from a secret marriage between the discontented Georgiana Podsnap and the vacuous socialite Fascination Fledgeby. The naieve, gullible Georgiana is the young woman sitting opposite the dark-haired, sharp-eyed, downward glancing, fashionably attired Mrs. Lammle in her drawing-room in the Lammles' temporary residence in Sackville Street, Piccadilly.

The woodcut for Book Two, "Birds of a Feather," Chapter Four, "Cupid Prompted," re-introduces Georgiana Podsnap from earlier in the novel: "an under-sized damsel, with high shoulders, low spirits, chilled elbows, a a rasped surface of nose" (Book One, Chapter 11). Despite the respectability of their Sackville Street parlour and correctness of their breakfast table, through their poses and sharp features illustrator Sol Eytinge reveals the couple's predatory natures more certainly than Mahoney's depiction of Alfred Lammle as a congenial husband in Georgiana's presence. As Dickens's text implies, the pair are hatching a scheme intent upon separating the wealthy Podsnap from some of his fortune by arranging a surreptitious marriage for his daughter. In his illustration for "Cupid Prompted," Eytinge implies the Lammles' being experts at sharp practice by the pointed nose (Dickens specifies he has "too much nose"), sharp fingers, and demonic grin of the husband, and the casual self-assurance of the wife, who even in private demonstrates the acute fashion sense that has rendered her a "consciously 'splendid woman'" in the Veneerings' social set. Emphasizing the rich draperies at the window and the elegance of the ladies' dresses and hairstyles, Mahoney like Eytinge suggests the Piccadilly townhouse's "handsome fittings and furnishings" through the table, although neither includes the mirror which reflects Sophronia Lammle's smirking expression as she deprecates Miss Podsnap just after the young lady has left the room.

Reverting to the plot involving the banker Podsnap, his discontented daughter, Georgiana, and the "confidence couple," the Lammles, Dickens begins "Cupid Prompted" with another series of society dinners. Very quickly, however, he shifts the scene to the handsomely furnished parlour at the Sackville Street, Piccadilly, townhouse of Sophronia and Alfred Lammle. Whereas Marcus Stone focuses on the society dinner staged by John Podsnap, the veneer of respectable society, Mahoney and Eytinge penetrate the brilliant surface to explore the machinations of the devious Lammles. Aware of the effectiveness of the representation of the social gathering in Marcus Stone's serial illustration for Book Two, Chapter Four, Bringing Him In, Mahoney has elected to focus on the Lammles' plotting to marry Georgiana Podsnap to Fledgeby. There is, however, little sense of playfulness or romance in Mahoney's somber trio, and Alfred is not nearly the handsome, young confidence man with the feral expression that Marcus Stone captures so well in the honeymoon illustration, The Happy Pair.

Is this blonde-bearded thirty-something husband in a professional suit an appropriate facsmile of Dickens's resilient swindler Alfred Lammle of the full, ginger muttonchop-sideburns? There is little here to distinguish his image from Mahoney's characterization of Eugene Wrayburn, except the sharp nose, as both have a similar appearance. While Dickens describes Alfred Lammle's mood as "playful" when he leans over his wife's chair, Mahoney's somber husband does not engage with her at all; indeed, he seems to be directing his thoughtful gaze towards the couple's visitor, whose face the reader cannot assess. Dickens emphasizes that Lammle wears an excessive amount of jewelry, and therefore "glitters" with "too much sparkle in his studs, his eyes, his buttons, his talk, his teeth" (I: 2). Unscrupulous and opportunistic, Alfred Lammle should look shifty and untrustworthy, despite his supreme self-confidence and social survival skills; unfortunately, Mahoney's characterization falls well short of this image.

The Garden on the Roof

Book 2 Chapter 5

Marcus Stone

Text Illustrated:

"Some final wooden steps conducted them, stooping under a low pent-house roof, to the house-top. Riah stood still, and, turning to his master, pointed out his guests.

Lizzie Hexam and Jenny Wren. For whom, perhaps with some old instinct of his race, the gentle Jew had spread a carpet. Seated on it, against no more romantic object than a blackened chimney-stack over which some humble creeper had been trained, they both pored over one book; both with attentive faces; Jenny with the sharper; Lizzie with the more perplexed. Another little book or two were lying near, and a common basket of common fruit, and another basket full of strings of beads and tinsel scraps. A few boxes of humble flowers and evergreens completed the garden; and the encompassing wilderness of dowager old chimneys twirled their cowls and fluttered their smoke, rather as if they were bridling, and fanning themselves, and looking on in a state of airy surprise.

Taking her eyes off the book, to test her memory of something in it, Lizzie was the first to see herself observed. As she rose, Miss Wren likewise became conscious, and said, irreverently addressing the great chief of the premises: 'Whoever you are, I can't get up, because my back's bad and my legs are queer.'

Commentary:

"Quite another side of Fascination Fledgeby is revealed in the November, 1864, part (Chapter 5 of the second book) when the youth visits his money-lending business, Pubsey & Co., at St. Mary Axe. In the scene by Stone, the dignified Jew, Riah, Fledgeby's front-man, conducts his employer onto the roof of the building, where Jenny Wren and Lizzie Hexam are reading.

The illustration brings out that familiar Dickens theme, the romantic side of everyday things. In the midst of a wilderness of blackened, smoke-spewing chimneys we encounter the contemplative oasis of Riah's roof-garden, appropriately occupied by the two young, lower-class women who make "book-learning" their holiday from workaday drudgery. The picture underscores the mutual affection of Lizzie and Jenny, and connects these characters to Riah and thence to Fledgeby, whose connection to Georgiana Podsnap and the Lammles bridges the gulf between the working and the upper classes. Stone has foiled the dozen chimneys and the sooty building behind Riah with the overgrown chimney-pots and greenery behind the picnicking young women. In the foreground is Jenny Wren's oversized bonnet, implying that, for the moment at least, she has been able to shed her role as pseudo-adult wage-earner and head of family to enjoy the liberation of an engrossing book."

Fledgeby and Riah

Book 2 Chapter 5

Sol Eytinge Jr.

1870

Household Edition

Commentary:

This second illustration for "Mercury Prompting," depicting the noble Jew Riah and his unscrupulous "Christian" employer, Fascination Fledgeby, connects three sets of minor characters through the "prompting" of the Roman deity of commerce, sharp business practice, and thieves: the Lammles, their associate Fledgeby, and his "front man" in usury, Riah. The venerable Jew whom Eytinge depicts is an accurate reflection of his description in the text, but is not entirely consistent with his depiction in the Marcus Stone woodcut "Miss Wren fixes Her Idea" in the 1865 Chapman and Hall volume. Marcus Stone does not utilize stereotypical images of Jews, and, although he includes a hat and staff as Riah's appurtenances, he does not give Riah a tattered, "long out of date" coat and balding head. True to Dickens's text, Eytinge gives us a supercilious Fledgeby and a subservient, bald Riah with patriarchal beard and somewhat ill-kempt long hair, an image consistent with such stereotypical Jews as Fagin:

"Now you sir!" cried Fledgeby. "These are nice games."

He addressed an old Jewish man in an ancient coat, long of skirt, and wide of pocket. A venerable man, bald and shining at the top of his head, and with long grey hair flowing down at its sides and mingling with his beard. A man who with a graceful Eastern action of homage bent his head, and stretched out his hands with the palms downward, as if to depreciate the wrath of a superior.

"What have you been up to?" said Fledgeby, storming at him.

However, since Fledgeby seems calm and self-possessed in the illustration, we must assume that Eytinge is conflating the above description of Riah with the following scene, in which Fledgeby continues his dialogue with his employee in the St. Mary Axe accounting office of Pubsey and Co. (realized in Eytinge's woodcut):

Fledgeby turned into the counting-house, perched himself on a business stool, and cocked his hat. There were light boxes on shelves in the counting-house, and strings of mock beads hanging up. There were samples of cheap clocks, and samples of cheap vases of flowers. Foreign toys, all.

Perched on the stool with his hat cocked on his head and one of his legs dangling, the youth of Fledgeby hardly contrasted to advantage with the age of the Jewish man as he stood with his bare head bowed, and his eyes (which he only raised in speaking) on the ground.

Since Marcus Stone worked closely with Dickens on the 1864-65 illustrations, and since Dickens was very much concerned that his characterization of Riah compensate for the perceived anti-Semitism of Fagin in Oliver Twist (1837-38), it seems likely that the more distinguished Riah of the Stone plate for the October 1865 installment represents Dickens's final intention for Fledgeby's assistant, adjusting the perception created by the description in the November 1864 installment.

Perched on the stool, with his hat cocked on his head, and one of his legs dangling, the youth of Fledgeby hardly contrasted to advantage with the age of the Jewish man as he stood with his bare head bowed.

Book 2 Chapter 5

J. Mahoney

Household Edition 1875

Commentary:

The woodcut for Book Two, "Birds of a Feather," Chapter Five, "Mercury Prompting," introduces Fascination Fledgeby in a very different light, for the callow, beardless junior member of the upper-middle-class social circle ruled by the Veneerings and Podsnaps, leads a double life as the ruthless owner of a money-lending establishment, Pubsey and Co. His associate, the pious Jew Riah, Morse has described as "too gentle to be a believable human being" (1976), and it is now generally acknowledged that Riah is in part Dickens's apology for the perceived anti-Semitism in the character of the criminal mastermind Fagin in Oliver Twist nearly thirty years earlier. While residing in Italy in 1844, Dickens had made considerable revisions to the early novel, consistently replacing "the Jew" with "Fagin," but the damage had been done, and Dickens realized something more was necessary. However, in "Eastern" garb, Riah strikes us as more of a Jewish fairy-godfather than an authentic, multi-dimensional character. Moreover, as Goldie Morgentaler has pointed out, the name "Riah" is no more Jewish than the name "Fagin," although at least his first name ("Aaron") has Judaic roots. "In part, Riah was Dickens's response to Mrs. Eliza Davis's objection to the anti-Semitic stereotyping in the portrayal of Fagin" (Davis, 338).

The setting of the Mahoney plate, the counting house owned in fact by the gambler and wastrel "Fascination" Fledgeby but ostensibly by the "exotic" Jew, Aaron Riah, is as significant as the characters whom Mahoney has positioned in the room, the true director of the firm enthroned, the apparent owner standing, making a gesture of supplication. Although Our Mutual Friend is about commerce, in it Dickens makes very few direct references to companies (as opposed to businesses such as Harmon's or Pottersons), other than Veneering's and Podsnap's. Fledgeby's spuriously named "Pubsey and Co." is not a corporation or limited company at all, although its name implies a founder (Pubsey) and partners; because the owner of this money-lending establishment is apparently a Jew, nobody bothers to interrogate the name or ownership of the firm. Remarks Riah in Book Two, Chapter 5, to his "Christian" employer that nobody believes him a mere poor employee:

Were I to say "This little fancy business is not mine;" with a lithe sweep of his easily-turning hand around him, to comprehend the various objects on the shelves; "it is the little business of a Christian young gentleman who places me, his servant, in trust and charge here, and to whom I am accountable for every single bead," they would laugh. When, in the larger money-business, I tell the borrowers —"

"I say, old chap!' interposed Fledgeby, 'I hope you mind what you do tell 'em?"

"Sir, I tell them no more than I am about to repeat. When I tell them, "I cannot promise this, I cannot answer for the other, I must see my principal, I have not the money, I am a poor man and it does not rest with me," they are so unbelieving and so impatient, that they sometimes curse me in Jehovah's name."

"That's deuced good, that is!" said Fascination Fledgeby.

According to Phoebe Poon, as a mercurial businessman (Mercury being the patron deity of thieves as well as merchants) Fledgeby has put a believable — indeed, a highly likely — face on his company: Riah's. Yet he speaks of the owners of the business as "they," implying a corporate board of shareholders (seven or more were required by the Companies Act of 1862 if the company could be regarded as an "incorporated" entity and its owners privileged to limited liability).

The illustrations involving Riah, Fledgeby, and the shop all show "strings of mock beads hanging up" (left) and "samples of cheap clocks, and samples of cheap vases of flowers" (rear). These wares are spurious, of course, since the real business of Pubsey & Co. is money-lending at extortionate rates of interest to people such as the Lammles. Exactly as Dickens has described him, Fledgeby has cocked his silk-hat to one side, and has mounted an accountant's stool. A supercilious look on his face, the young "Christian" businessman addresses Riah disrespectfully, but Riah, his pose exactly as Dickens describes him, does not respond to his employer's sarcasm. In Mahoney's illustration we do not see Riah's broad-brimmed hat hanging on the wall, but we have many of the elements seen in Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Fledgeby and Riah, notably the clocks and other properties described in the text; however, Mahoney also includes an accountant's desk, several filing-cabinets (behind Riah, left), and a wastepaper basket (centre rear).

"Come up and be dead! Come up and be dead!"

Book 2 Chapter 5

J. Mahoney

Household Edition 1875

Commentary:

"The actual wording of the caption, as spoken by Jenny Wren, should be, "Come back and be dead, Come back and be dead!" The scene is the roof of Fledgeby's shop, Pubsey & Co., in Saint Mary Axe. Fledgeby, having upbraided his employee, Riah, for keeping the door locked on holiday, accompanies him up to the roof, as in Marcus Stone's The Garden on the Roof, originally in Part 7 (November 1864). Both the Stone original and the Mahoney re-interpretation allude obliquely to Dickens's desire to see the "greening" of London, often expressed in such editorials as "Lungs for London" in Household Words (3 August 1850) and which eventually led to the creation of such public parks as Finsbury.

The woodcut for Book Two, "Birds of a Feather," Chapter Five, "Mercury Prompting," introduces Fascination Fledgeby to Lizzie Hexam and Jenny Wren, who use the roof of Pubsey & Co. as if it were a park in the midst of the city. In Mahoney's illustration, we do not see Riah's companion, Fascination Fledgeby, but only Riah, scrambling up to the roof, and Lizzie and Jenny. Presumably, Fledgeby is immediately below Riah on the stairs. Bearded and wearing gabardine like the stereotype established by Shakespeare's Shylock in The Merchant of Venice, Riah here looks much as he does in Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Fledgeby and Riah, notably long, grey locks and gabardine; however, Mahoney is relying exclusively on the original Marcus Stone illustration The Garden on the Roof (November 1864). The scene, underscoring the romance in everyday things, brings together members of the working-class, Riah, Jenny, and Lizzie, and the upper-middle-class businessman Fledgeby. Marcus Stone underscores the mutual affection of Lizzie and Jenny, and connects these characters to Riah and thence to Fledgeby, whose connection to Georgiana Podsnap and the Lammles bridges the gulf between the working and the upper classes. Stone has foiled the dozen chimneys and the sooty building behind Riah with the overgrown chimney-pots and greenery behind the picnicking young women. In the foreground is Jenny Wren's oversized bonnet, implying that, for the moment at least, she has been able to shed her role as pseudo-adult wage-earner and head of family to enjoy the liberation of an engrossing book. The situation and composition are very different in the Mahoney illustration, which focuses on the standing figure of Lizzie Hexam, reduces the garden aspect of the setting somewhat, and eliminates Riah's employer entirely. The chimneys are now but shadowy presences as both Lizzie and Jenny react to Riah's arrival on the rooftop. To the right, just discernible, are "a common basket of common fruit, and another basket full of strings of beads and tinsel scraps" — although the viewer must read the accompanying text, presented simultaneously with the illustration, to determine what precisely the woven baskets contain. In other words, a fully independent reading of the wood-engraving is impossible as the context and meaning of objects within the frame, including Jenny's crutch and books (down centre), can only be ascertained through a reading of Dickens's words. Moreover, in this instance, Mahoney is alluding to the Stone antecedent of the Household Edition, which more clearly defines the smoky London cityscape behind the figures, and shows both Fledgeby (upper right), the chimney-pots, as well as Jenny's basket and the blanket that Riah has spread for the young women. The relationship between the two illustrations is one of time sequence, for Stone's depiction of the rooftop should proceed that of Mahoney as in the latter both girls have noticed the visitor, and Lizzie is now standing. Fledgeby, therefore, ought to be present as he is one of the principal interlocutors in the dialogue."

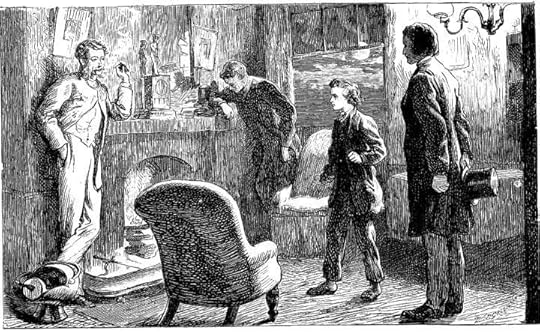

Forming The Domestic Virtues

Book 2 Chapter 6

Marcus Stone

Commentary:

Working Class and Upper-Middle Class Worlds Collide: Charlie Hexam and Bradley Headstone visit Mortimer Lightwood and Eugene Wrayburn in their chambers

In the November 1864 monthly number, Marcus Stone realizes the moment at which Charlie Hexam and his mentor, the schoolmaster Bradley Headstone, confront Eugene Wrayburn about his interest in Lizzie, a confrontation loaded with class-consciousness and antipathy as the working-class brother suspects that the indolent, upper-middle-class attorney means to exploit his sister sexually. The scene, set in the Temple, in the rooms (as opposed to the offices) of the attorneys Eugene Wrayburn and Mortimer Lightwood, confirms the latter's suspicions that something is deeply troubling his friend. In fact, Bradley Headstone and his star pupil, Charlie Hexam, have dared to venture outside their working-class milieu to demand that Eugene severe his relationship with Lizzie.

For those unacquainted with Victorian London, the Inns of Court — the Middle Temple, the Staple Inn and the Inner Temple — occupy the area between Fleet Street and the Thames; and here Pip and his friend Herbert Pocket had rooms in Garden Court in Great Expectations (1861). The area takes its name from the Order of the Knights Templar, who owned these properties in the Middle Ages. Nearby is Temple Bar, which separates the City of London from the City of Westminster.

Moment realized in this illustration:

Both the wanderers looked up towards the window; but, after interchanging a mutter or two, soon applied themselves to the door-posts below. There they seemed to discover what they wanted, for they disappeared. from view by entering at the doorway. 'When they emerge,' said Eugene, 'you shall see me bring them both down;' and so prepared two pellets for the purpose.

He had not reckoned on their seeking his name, or Lightwood's. But either the one or the other would seem to be in question, for there came a knock at the door. 'I am on duty to-night,' said Mortimer, 'stay you where you are, Eugene.' Requiring no persuasion, he stayed there, smoking quietly, and not at all curious to know who knocked, until Mortimer spoke to him from within the room, and touched him. Then, drawing in his head, he he found the visitors to be young Charley Hexam and the schoolmaster; both standing facing him, and both recognised at a glance.

'You recollect this young fellow, Eugene?' said Mortimer.

'Let me look at him,' returned Wrayburn, coolly. 'Oh, yes, yes. I recollect him!'

He had not been about to repeat that former action of taking him by the chin, but the boy had suspected him of it, and had thrown up his arm with an angry start. Laughingly, Wrayburn looked to Lightwood for an explanation of this odd visit.

'He says he has something to say.'

'Surely it must be to you, Mortimer.'

'So I thought, but he says no. He says it is to you.'

'Yes, I do say so,' interposed the boy. 'And I mean to say what I want to say, too, Mr. Eugene Wrayburn!'

Passing him with his eyes as if there were nothing where he stood, Eugene looked onto Bradley Headstone. With consummate indolence, he turned to Mortimer, inquiring: 'And who may this other person be?'

'I am Charles Hexam's friend,' said Bradley, 'I am Charles Hexam's schoolmaster.'

'My good sir, you should teach your pupils better manners,' returned Eugene.

Composedly smoking, he leaned an elbow on the chimney-piece, at the side of the fire, and looked at in the schoolmaster. It was a cruel look, in its cool disdain of him, as a creature of no worth. The schoolmaster looked at him, and that, was a cruel look, though of the different kind, that it had a raging jealousy and fiery wrath in it.

Very remarkably, neither Eugene Wrayburn nor Bradley Headstone looked at all at the boy. Through the ensuing dialogue, those two, no matter who spoke, or whom was addressed, looked at each other. There was some secret, sure perception between them, which set them against one another in all ways.

The composition complements, too, the running heads of the page between the reader's encountering the illustration, facing page — "Mortimer's Suspicions" — and that of the page realized, "Visitors to Mr. Eugene Wrayburn", which explain Mortimer Lightwood's anguished pose and the context of the illustration the reader has just seen. Like the best illustrations of such earlier visual commentators as John Leech, George Cruikshank, and Phiz (Hablot Knight Browne) this woodcut by Marcus Stone prepares the reader for a significant event in the narrative and compels the reader to be more attentive to nuances of the text that shed light on the characters' motivations, attitudes, and relationships. The illustration itself reflects the juxtapositions of the figures which Dickens describes in the pages immediately following the picture, which is therefore a reflection of the text, just as Eugene is a reflection of Mortimer and Charlie is a reflection of Bradley; the central visual metaphor of the woodcut, therefore, is the mirror above the mantelpiece in which the figurine atop the clock is reflected and into whose frame correspondence and cards have been jammed. With little to go on other than Dickens's descriptions of the figures themselves and their utterances, Stone has provided the standard furnishings for the upper-middle class bachelors' rooms: a coal burning fire-place with a clock on the mantle and a brass fender, coal scuttle, and poker (lower left); a brace of easy-chairs, a nondescript carpet, a table, a gasolier (upper right); and to either side of the fire-place a pair of pictures that complement the dualities in the scene: two sets of characters from two entirely different classes pursuing different agendas. The placement and title of these pictures — which in a Phiz illustration would have definite subjects reflecting the nature of the conflict, but which in Stone are merely a vehicle for drawing the viewer's attention away from the central figure, Charlie, towards the two lawyers — complements the contrasting postures of Lightwood and Wrayburn, whose extremely casual stance and smoking as he leans an elbow on the mantle the text describes most particularly, so that both media focus the reader's attention on Eugene ("Well-born") Wrayburn.

Behind Charlie's head are such naturalistic details as a full moon, clouds, and a darkened skyline, indicating the time of day and the proximity of these rooms to the great river which connects the lives of so many of the characters in the novel. The Schoolmaster and his protégé come from that larger, grittier world but dimly apprehended from the window of the comfortable upper-middle class bachelors' room. The frock coats of all four males reveal their professional status (at least in the case of the attorneys) or their aspirations to professional status (in the case of the teacher and his monitor). The proper, middle-class top-hat and dark wool coat convey Bradley Headstone's sense of himself as a member of an emerging profession in the decade preceding the General Education Act.

The focus of the figures' attentions is, however, the indolent figure of Eugene Wrayburn, whom Charlie will shortly warn off his sister. In the scene, the Schoolmaster seems a rigid pillar, firm, physically commanding, and self-controlled; his shadowed face, seen only in profile, communicates no emotion. The picture therefore betrays no sense of Headstone's growing anxiety at being taunted by a social superior; we do not notice "pale and quivering lips" which prepare us for Bradley's being driven "well-nigh mad" by the supercilious Eugene's goading.

Eugene, as in the subsequent passage, regards the Schoolmaster with a "disinterested" air and ignores Charlie completely. Stone depicts Eugene standing to the other side of the fire-place, his friend Mortimer on the other side, by the window, and the boy caught in the middle. Eugene does indeed have a hair-guard for his watch, but Stone has again extended the text by supplying the waistcoat and fashionable trousers. Between his sister's admirer and his mentor stands Charlie, serious and (as the position of his raised left hand suggests) determined to be heard by those taller and more powerful than himself.

An interesting aspect of Stone's composition is the fourth figure's posture: Mortimer Lightwood has literally receded into the background, keeping his head down, not regarding any of the other characters, but listening attentively (as in the text, he is nearest the window, but is not looking out). In contrast to this anguished pose is Eugene'; he exudes "attitude" as he enjoys his cigar and tormenting Headstone with "perfect placidity" designed to infuriate and belittle his interlocutors. The picture thus sets up expectations in the reader as to what he or she will momentarily encounter in the print medium; at the moment of realization, the reader undoubtedly went back in the text, seeking to decode the characters' postures and expressions.

Kim wrote: ""Come up and be dead! Come up and be dead!"

Book 2 Chapter 5

J. Mahoney

Household Edition 1875

Commentary:

"The actual wording of the caption, as spoken by Jenny Wren, should be, "Come back an..."

I enjoyed the commentary that accompanied this illustration very much. To me, the rooftop garden is a key element in the text, and it's always re-assuring to see that others agree. :-)). As we have read through Dickens, I have been made aware how important a study/understanding of "Household Words" is to grasp a fuller understanding and appreciation of Dickens. In this commentary we read of an editorial titled "Lungs for London." Who knew that Dickens was an early environmentalist?

I found the actual illustration enjoyable as well. There is much detail. The illustration tells a story itself rather than just being an accompaniment to the letterpress.

Book 2 Chapter 5

J. Mahoney

Household Edition 1875

Commentary:

"The actual wording of the caption, as spoken by Jenny Wren, should be, "Come back an..."

I enjoyed the commentary that accompanied this illustration very much. To me, the rooftop garden is a key element in the text, and it's always re-assuring to see that others agree. :-)). As we have read through Dickens, I have been made aware how important a study/understanding of "Household Words" is to grasp a fuller understanding and appreciation of Dickens. In this commentary we read of an editorial titled "Lungs for London." Who knew that Dickens was an early environmentalist?

I found the actual illustration enjoyable as well. There is much detail. The illustration tells a story itself rather than just being an accompaniment to the letterpress.

Kim wrote: "Forming The Domestic Virtues

Book 2 Chapter 6

Marcus Stone

Commentary:

Working Class and Upper-Middle Class Worlds Collide: Charlie Hexam and Bradley Headstone visit Mortimer Lightwood and Euge..."

First, as always Kim. Thank you. The posting of these illustrations really enhances and deepens our understanding and appreciation of Dickens.

I really like the work of Marcus Stone. There is so much detail. I feel in his work an understanding of not only how to portray the plot of the story but also a detailed and creative expression that goes beyond mere plot and enters into true art.

The commentary to this illustration was very insightful. The comments on the clothing, the mirror, the physical pose of the characters and the peripheral details such as what is seen out the window all combine to broaden and deepen my understanding. Over and over, I find that by studying the illustrations and reading the commentaries I am becoming better tuned to the novel itself.

A delight.

Book 2 Chapter 6

Marcus Stone

Commentary:

Working Class and Upper-Middle Class Worlds Collide: Charlie Hexam and Bradley Headstone visit Mortimer Lightwood and Euge..."

First, as always Kim. Thank you. The posting of these illustrations really enhances and deepens our understanding and appreciation of Dickens.

I really like the work of Marcus Stone. There is so much detail. I feel in his work an understanding of not only how to portray the plot of the story but also a detailed and creative expression that goes beyond mere plot and enters into true art.

The commentary to this illustration was very insightful. The comments on the clothing, the mirror, the physical pose of the characters and the peripheral details such as what is seen out the window all combine to broaden and deepen my understanding. Over and over, I find that by studying the illustrations and reading the commentaries I am becoming better tuned to the novel itself.

A delight.

I was curious if anyone detected any particular word or image related to the Lammles?

I was curious if anyone detected any particular word or image related to the Lammles? I say the name, I hear lambs. I look at the name, I see laminate. I sense something there, though unsure.

LindaH wrote: "Since Dickens has been playing with riddles and nursery rhymes, I am emboldened to play at making paper chains, specifically chains of characters.

Chain the first:

Tremlow is linked to the Veneer..."

Linda,

Thanks for pointing out the connections between the characters! I think this is very important because it shows that after all, for all the seemingly disrupted structure of the novel, there is a masterplan somewhere in the wings. Things will be connected more and more, I'm sure.

Chain the first:

Tremlow is linked to the Veneer..."

Linda,

Thanks for pointing out the connections between the characters! I think this is very important because it shows that after all, for all the seemingly disrupted structure of the novel, there is a masterplan somewhere in the wings. Things will be connected more and more, I'm sure.

I agree, Tristram. Dickens' master plan is finally becoming apparent in this week's reading. Two new characters, Fledgeby and Riah, nicely bridge the gap between Podsnappery and Jenny Wren.

I agree, Tristram. Dickens' master plan is finally becoming apparent in this week's reading. Two new characters, Fledgeby and Riah, nicely bridge the gap between Podsnappery and Jenny Wren. There's at least one con afoot, thanks to the Lammles. We know that Georgiana is the mark...is Fledgeby a mark too? His money seems questionable. And what about Riderhood...he has tried to con his way to the reward? What is he capable of doing? And Wegg is a suspicious fellow, his eyes taking in everything at the Boffins' as he sells himself as a learned man.

My sympathies are with the Boffins, Lizzie and Jenny Wren.

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 6 takes up some other characters but is also, indirectly, connected with what we have seen in the last chapter. It also proclaims to give us “A Riddle Without an Answer”. It brings us back ..."

Mortimer and Eugene are a nasty pair of lawyers. it's hard to decide whether Dickens disliked lawyers or teachers more. There is such a languid and indolent tone to their voices, to their actions, and in their morals. Did anyone else feel these characters as being precursors to Oscar Wilde's style of character development?

OMF seems to have more dislikable characters than any other Dickens novel. This chapter is another that seems to pit the young and naive against the mean spirited. Recently we had poor Georgiana against the Lammle's which was certainly an unfair contest. Folded into this paring was the Lammle's against Fledgeby. Layers upon layers of character conflicts. Riah versus Fledgeby is another conflict of power, position and money that has been introduced.

Dickens is building up characters, motifs and conflicts. It's like watching a massive storm brewing. We see and feel it coming.

Mortimer and Eugene are a nasty pair of lawyers. it's hard to decide whether Dickens disliked lawyers or teachers more. There is such a languid and indolent tone to their voices, to their actions, and in their morals. Did anyone else feel these characters as being precursors to Oscar Wilde's style of character development?

OMF seems to have more dislikable characters than any other Dickens novel. This chapter is another that seems to pit the young and naive against the mean spirited. Recently we had poor Georgiana against the Lammle's which was certainly an unfair contest. Folded into this paring was the Lammle's against Fledgeby. Layers upon layers of character conflicts. Riah versus Fledgeby is another conflict of power, position and money that has been introduced.

Dickens is building up characters, motifs and conflicts. It's like watching a massive storm brewing. We see and feel it coming.

Peter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Chapter 6 takes up some other characters but is also, indirectly, connected with what we have seen in the last chapter. It also proclaims to give us “A Riddle Without an Answer”. I..."

Peter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Chapter 6 takes up some other characters but is also, indirectly, connected with what we have seen in the last chapter. It also proclaims to give us “A Riddle Without an Answer”. I..."Agree, and I find it for lack of a better word, disconcerting. He's really taking aim at a few things he had on his mind and he's doing it through characterization clearly. I feel he is quite the different person than the one who wrote Pickwick. But, perhaps, as it should be.

Linda and Peter,

Your posts made me think about another motif that seems to be at the top of Dickens's list here: Deception. Many of the characters here are in a way deceivers:

1) Wegg, as Linda says, poses as a man of letters whereas he is anything but a scholar.

2) The Lammles deceived each other and now they have entered in league against the whole of society, which they want to deceive.

3) The Veneerings want to hush up their status of nouveaux riches by pretending to be old friends with everyone around them.

4) Eugene and Mortimer pretend to be lawyers. Okay, they are lawyers but they have no real footing in the business, and Mortimer's clerk is a master at (self)deception when it comes to pretending that his employer has a full schedule.

5) Bella pretends, or has to pretend, to be in mourning over a husband she never knew.

6) Riderhood pretends that Hexam committed a crime in order to cash in on the reward.

These are all the instances of deception that have come into my mind on the spur of the moment. Maybe, there are others still?

Your posts made me think about another motif that seems to be at the top of Dickens's list here: Deception. Many of the characters here are in a way deceivers:

1) Wegg, as Linda says, poses as a man of letters whereas he is anything but a scholar.

2) The Lammles deceived each other and now they have entered in league against the whole of society, which they want to deceive.

3) The Veneerings want to hush up their status of nouveaux riches by pretending to be old friends with everyone around them.

4) Eugene and Mortimer pretend to be lawyers. Okay, they are lawyers but they have no real footing in the business, and Mortimer's clerk is a master at (self)deception when it comes to pretending that his employer has a full schedule.

5) Bella pretends, or has to pretend, to be in mourning over a husband she never knew.

6) Riderhood pretends that Hexam committed a crime in order to cash in on the reward.

These are all the instances of deception that have come into my mind on the spur of the moment. Maybe, there are others still?

Tristram wrote: "Linda and Peter,

Tristram wrote: "Linda and Peter,Your posts made me think about another motif that seems to be at the top of Dickens's list here: Deception. Many of the characters here are in a way deceivers:

1) Wegg, as Linda ..."

We can't really say Rokesmith is deceptive (at least not yet), but he's certainly hiding something.

Something interesting I came across this morning in the vein of the characters in this book.

Something interesting I came across this morning in the vein of the characters in this book.I pulled out my coffee table copy of Paul Davis' Charles Dickens - A to Z. It is quite excellent, by the way.

In some of the commentary in there, aside from straight description of the book, it indicates that OMF was likely the most difficult novel for Dickens to write. Obviously health and personal matters at the time, but the sense was he struggled with the characters and was attempting to find among them the best to build the story around.

John, that's an interesting piece of information, that Dickens struggled with the storyline, after introducing such remarkable characters from all walks of life. I would never have thought he didn't know where he was headed when he began. Or maybe he did know, just not how to get there. Okay, then...I like to think he challenged himself by NOT having a plot in mind.*. The added challenge, of course, was the constraint of serial publication.

John, that's an interesting piece of information, that Dickens struggled with the storyline, after introducing such remarkable characters from all walks of life. I would never have thought he didn't know where he was headed when he began. Or maybe he did know, just not how to get there. Okay, then...I like to think he challenged himself by NOT having a plot in mind.*. The added challenge, of course, was the constraint of serial publication. Peter, you have suggested Dickens welcomed challenges as a distraction from his personal problems. Do you think it was hubris too?

*The appearance of Jenny Wren in Lizzie's life is perhaps the biggest tipoff.

Tristram wrote: "Linda and Peter,

Your posts made me think about another motif that seems to be at the top of Dickens's list here: Deception. Many of the characters here are in a way deceivers:

1) Wegg, as Linda ..."

I certainly agree with you that deception is a strong motif. You have listed many characters who through deception become, project or act out what they are not.

Could we take the concept of deception even further and suggest that even a person's name could be deceptive. Now Dickens usually telegraphs his characters' personalities accurately by their name, but could this novel be different? We'll see.

Also, objects can be deceptive as well. When is a dust heap simply a dust heap? Is the Thames really a mutual friend? What does the phrase the golden dustman really imply?

Layers upon layers of intricate plot evolution.

Your posts made me think about another motif that seems to be at the top of Dickens's list here: Deception. Many of the characters here are in a way deceivers:

1) Wegg, as Linda ..."

I certainly agree with you that deception is a strong motif. You have listed many characters who through deception become, project or act out what they are not.

Could we take the concept of deception even further and suggest that even a person's name could be deceptive. Now Dickens usually telegraphs his characters' personalities accurately by their name, but could this novel be different? We'll see.

Also, objects can be deceptive as well. When is a dust heap simply a dust heap? Is the Thames really a mutual friend? What does the phrase the golden dustman really imply?

Layers upon layers of intricate plot evolution.

LindaH wrote: "John, that's an interesting piece of information, that Dickens struggled with the storyline, after introducing such remarkable characters from all walks of life. I would never have thought he didn'..."

Hi Linda

You ask a massive question. As to whether he welcomed challenges as a distraction from his personal problems I would say yes. He loved to work, to write and to do readings and these activities kept him very busy. Was he was becoming subject to hubris? I would say basically no.

As you know, there are many biographies of Dickens that have peeked, prodded, speculated and overturned seemingly every stone of his life. Like most Dickens fans, I accept what I want to accept, reject what I don't want to believe, and rationalize the rest. I have recently read The Other Dickens: A Life of Catherine Hogarth which is the biography of his wife Catherine. This book is thoroughly researched and contains much that is not flattering to him. I also recently read (as you can see I'm on a Dickens roll lately) Great Expectations: The Sons and Daughters of Charles Dickens which studies the relationship Dickens had with his children. Again, Dickens does not come across as a perfect father by any means. Then there is Claire Tomalin's Invisible Woman and we have Dickens living, or hiding, a very complicated and no doubt distracted life as he was wrote OMF.

As to Dickens and hubris ... We know Dickens was a very kind and thoughtful man as well, even when we consider the information in the books listed above. He was constantly the champion and an active participant in fighting for what he believed and the social causes he supported. With his health declining we also know that he wanted a no fuss funeral. He did not want anything grand to follow his life such as statues or memorials. He did not seek the constant attention of royalty and only met once with Queen Victoria, and then, evidently, reluctantly. History records that in that meeting he was going to tell the Queen the ending of Edwin Drood but she declined his offer and wanted to be kept in suspense too.

Ultimately, I think Charles Dickens was not a man of great hubris, although he certainly was well aware of his position in the eyes of the world.

Like great people, and like us all really, he was a person with many facets, many contradictions and several secrets. It was his immense talent that thrust him into the spotlight and thus put him under the unrelenting eye of the world.

Hi Linda

You ask a massive question. As to whether he welcomed challenges as a distraction from his personal problems I would say yes. He loved to work, to write and to do readings and these activities kept him very busy. Was he was becoming subject to hubris? I would say basically no.

As you know, there are many biographies of Dickens that have peeked, prodded, speculated and overturned seemingly every stone of his life. Like most Dickens fans, I accept what I want to accept, reject what I don't want to believe, and rationalize the rest. I have recently read The Other Dickens: A Life of Catherine Hogarth which is the biography of his wife Catherine. This book is thoroughly researched and contains much that is not flattering to him. I also recently read (as you can see I'm on a Dickens roll lately) Great Expectations: The Sons and Daughters of Charles Dickens which studies the relationship Dickens had with his children. Again, Dickens does not come across as a perfect father by any means. Then there is Claire Tomalin's Invisible Woman and we have Dickens living, or hiding, a very complicated and no doubt distracted life as he was wrote OMF.