The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Our Mutual Friend

Our Mutual Friend

>

OMF, Book 1 Chp. 01-04

Peter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Our fourth Chapter introduces us to „The R. Wilfer Family”, but we quickly notice that, although another set of new characters is put onto the stage, Dickens’s world is small and f..."

If there's one thing that reading Dickens's novels with the group has taught me - and it has taught me more things than one - then that there are quite some multi-facetted female characters in Dickens. Just remember Lady Dedlock and Edith Dombey, whose inner plight becomes obvious in a close reading of the text. Then there's Estella, of course, and we also talked a lot about a side-character like Mrs. Joe. One of Dickens's earlier female characters that undergo some development is Mercy Pecksniff, but one may argue that in her case, the development is not quite so subtle but more moralistic.

If there's one thing that reading Dickens's novels with the group has taught me - and it has taught me more things than one - then that there are quite some multi-facetted female characters in Dickens. Just remember Lady Dedlock and Edith Dombey, whose inner plight becomes obvious in a close reading of the text. Then there's Estella, of course, and we also talked a lot about a side-character like Mrs. Joe. One of Dickens's earlier female characters that undergo some development is Mercy Pecksniff, but one may argue that in her case, the development is not quite so subtle but more moralistic.

Tristram wrote: "John wrote: "Tristram,

Tristram wrote: "John wrote: "Tristram,From everything I've read through the years, most literary reviewers believe Bleak House was his best. I think of people like Harold Bloom and Charles Van Doren and others. ..."

I actually have an old trade paperback of Martin Chuzzlewit. It's as thick as a cinderblock and it is tough for me to compare to my Bleak House, which is a mass market paperback.

This got me to thinking -- in word count terms -- which book of Dickens is his longest?

Anyone know? I'd hazard a guess at BH, but not sure.

John wrote: "and I was still unsure whether Twemlow was a human being or a piece of furniture."

I'd rather see that as testimony to how brilliantly Dickens describes the scene here, i.e. showing how void of real life the dinner party guests and their hosts actually are. I do like Dickens best when he is at his most satirical, or when he introduces us to his most quirky characters.

Lady Tippins's "face in a tablespoon" I took as a vary long and horsey face, and the rest of the sentence seemed to refer to me to a badfy fitted wig, as Peter said. By the way, the reference Mary Lou was looking for is in the short story "Hunted Down" where Dickens made much of the parting on a fraudulent life insurance taker's head, the parting being a visual metaphor for leading someone up the garden path.

What the Veneerings have to hide is probably the fact that they actually don't have anything to hide, except their being social climbers, which is why they are keen on giving dinner parties and making new acquaintances. The more people they know, the less obvious it might be that they are relatively "new" in their social circle. It's this shallowness, I think, that is also expressed in the label of the "well-looking, veiled-prophet, not prophesying". One corner of this veil, i.e. of the social pretension, is also on Mrs. Veneering because she is sitting in her husband's boat. - Those are just my ideas.

I'd rather see that as testimony to how brilliantly Dickens describes the scene here, i.e. showing how void of real life the dinner party guests and their hosts actually are. I do like Dickens best when he is at his most satirical, or when he introduces us to his most quirky characters.

Lady Tippins's "face in a tablespoon" I took as a vary long and horsey face, and the rest of the sentence seemed to refer to me to a badfy fitted wig, as Peter said. By the way, the reference Mary Lou was looking for is in the short story "Hunted Down" where Dickens made much of the parting on a fraudulent life insurance taker's head, the parting being a visual metaphor for leading someone up the garden path.

What the Veneerings have to hide is probably the fact that they actually don't have anything to hide, except their being social climbers, which is why they are keen on giving dinner parties and making new acquaintances. The more people they know, the less obvious it might be that they are relatively "new" in their social circle. It's this shallowness, I think, that is also expressed in the label of the "well-looking, veiled-prophet, not prophesying". One corner of this veil, i.e. of the social pretension, is also on Mrs. Veneering because she is sitting in her husband's boat. - Those are just my ideas.

John wrote: "Tristram wrote: "John wrote: "Tristram,

From everything I've read through the years, most literary reviewers believe Bleak House was his best. I think of people like Harold Bloom and Charles Van D..."

I'd also think it was BH but then also Dombey and OMF come to my mind. Pickwick is also quite long.

From everything I've read through the years, most literary reviewers believe Bleak House was his best. I think of people like Harold Bloom and Charles Van D..."

I'd also think it was BH but then also Dombey and OMF come to my mind. Pickwick is also quite long.

Everyman wrote: "The Gutenberg.org edition has illustrations which may be the original illustrations -- can you tell, Kim?"

Yes. They are by Marcus Stone. He was the first illustrator although, as usual, more came along after him. I'm getting the illustrations now.

Here is an introduction to Marcus Stone and his illustrations:

"According to Frederic G. Kitton's 1899 study of the novelist and his illustrators, Marcus Stone had an unusual relationship with Dickens, who granted him considerable freedom in choosing his subjects:

It is a recognized fact among illustrators of works of fiction that authors are usually devoid of what Mr. Stone aptly designates a sense of " pictorialism," — that is to say, the subjects selected by them for illustration invariably prove to be unsuitable. Charles Dickens (according to Mr. Stone's experience) was a noteworthy exception to the rule, although he usually afforded the artist free scope in this matter, sending him the revised proof-sheets of each number, that he might make his own choice of the incidents to be depicted; and it is worthy of remark that in no instance did the novelist question the propriety of his selection. A preliminary sketch for each illustration was forwarded to Dickens, who returned it to the artist with suggestions, and with the title inscribed by him in the margin. The finished drawings upon the wood were never seen by the novelist, as they were dispatched by Mr. Stone to the engravers immediately on completion.

Despite enjoying this freedom in choosing passages to illustrate, Stone found that the novelist's earlier work-practice with Phiz, which involved giving detailed directions about composition and often symbolic details, led to delays in completing the individual plates:

Mr. Marcus Stone affirms that he was much hampered by Dickens with respect to these designs, for the novelist, hitherto accustomed to the diminutive scale of the figures in Hablot Browne's etchings, was somewhat imperative in his demand for a similar treatment of the illustrations for "Our Mutual Friend." The author, it seems, was usually in an appreciative mood whenever a sketch was submitted for approval, now and then favoring his illustrator with information that often proved indispensable.

In his previous collaborative relationship, that with Hablot Knight Browne, Dickens was accustomed to give highly specific directions for each composition, and to require that artist submit to him the sketches in draft for criticism and approval, necessitating some considerable delay in the illustrator's submitting his finished work to the publisher in time for the next monthly installment."

Yes. They are by Marcus Stone. He was the first illustrator although, as usual, more came along after him. I'm getting the illustrations now.

Here is an introduction to Marcus Stone and his illustrations:

"According to Frederic G. Kitton's 1899 study of the novelist and his illustrators, Marcus Stone had an unusual relationship with Dickens, who granted him considerable freedom in choosing his subjects:

It is a recognized fact among illustrators of works of fiction that authors are usually devoid of what Mr. Stone aptly designates a sense of " pictorialism," — that is to say, the subjects selected by them for illustration invariably prove to be unsuitable. Charles Dickens (according to Mr. Stone's experience) was a noteworthy exception to the rule, although he usually afforded the artist free scope in this matter, sending him the revised proof-sheets of each number, that he might make his own choice of the incidents to be depicted; and it is worthy of remark that in no instance did the novelist question the propriety of his selection. A preliminary sketch for each illustration was forwarded to Dickens, who returned it to the artist with suggestions, and with the title inscribed by him in the margin. The finished drawings upon the wood were never seen by the novelist, as they were dispatched by Mr. Stone to the engravers immediately on completion.

Despite enjoying this freedom in choosing passages to illustrate, Stone found that the novelist's earlier work-practice with Phiz, which involved giving detailed directions about composition and often symbolic details, led to delays in completing the individual plates:

Mr. Marcus Stone affirms that he was much hampered by Dickens with respect to these designs, for the novelist, hitherto accustomed to the diminutive scale of the figures in Hablot Browne's etchings, was somewhat imperative in his demand for a similar treatment of the illustrations for "Our Mutual Friend." The author, it seems, was usually in an appreciative mood whenever a sketch was submitted for approval, now and then favoring his illustrator with information that often proved indispensable.

In his previous collaborative relationship, that with Hablot Knight Browne, Dickens was accustomed to give highly specific directions for each composition, and to require that artist submit to him the sketches in draft for criticism and approval, necessitating some considerable delay in the illustrator's submitting his finished work to the publisher in time for the next monthly installment."

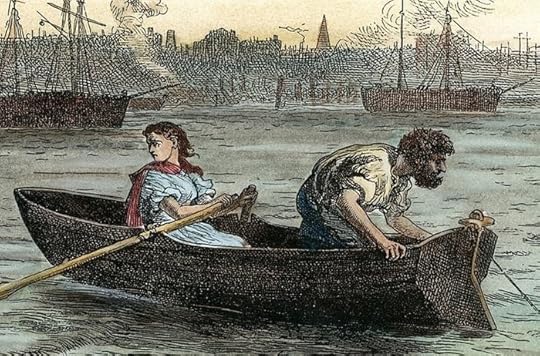

"The Bird of Prey"

Marcus Stone

1864

Text Illustrated:

"The figures in this boat were those of a strong man with ragged grizzled hair and a sun-browned face, and a dark girl of nineteen or twenty, sufficiently like him to be recognizable as his daughter. The girl rowed, pulling a pair of sculls very easily; the man, with the rudder-lines slack in his hands, and his hands loose in his waistband, kept an eager look out. He had no net, hook, or line, and he could not be a fisherman; his boat had no cushion for a sitter, no paint, no inscription, no appliance beyond a rusty boathook and a coil of rope, and he could not be a waterman; his boat was too crazy and too small to take in cargo for delivery, and he could not be a lighterman or river-carrier; there was no clue to what he looked for, but he looked for something, with a most intent and searching gaze. The tide, which had turned an hour before, was running down, and his eyes watched every little race and eddy in its broad sweep, as the boat made slight head-way against it, or drove stern foremost before it, according as he directed his daughter by a movement of his head. She watched his face as earnestly as he watched the river. But, in the intensity of her look there was a touch of dread or horror.

Allied to the bottom of the river rather than the surface, by reason of the slime and ooze with which it was covered, and its sodden state, this boat and the two figures in it obviously were doing something that they often did, and were seeking what they often sought. Half savage as the man showed, with no covering on his matted head, with his brown arms bare to between the elbow and the shoulder, with the loose knot of a looser kerchief lying low on his bare breast in a wilderness of beard and whisker, with such dress as he wore seeming to be made out of the mud that begrimed his boat, still there was a business-like usage in his steady gaze. So with every lithe action of the girl, with every turn of her wrist, perhaps most of all with her look of dread or horror; they were things of usage.

‘Keep her out, Lizzie. Tide runs strong here. Keep her well afore the sweep of it.’

Trusting to the girl’s skill and making no use of the rudder, he eyed the coming tide with an absorbed attention. So the girl eyed him. But, it happened now, that a slant of light from the setting sun glanced into the bottom of the boat, and, touching a rotten stain there which bore some resemblance to the outline of a muffled human form, coloured it as though with diluted blood. This caught the girl’s eye, and she shivered.

‘What ails you?’ said the man, immediately aware of it, though so intent on the advancing waters; ‘I see nothing afloat.’

The red light was gone, the shudder was gone, and his gaze, which had come back to the boat for a moment, travelled away again. Wheresoever the strong tide met with an impediment, his gaze paused for an instant. At every mooring-chain and rope, at every stationery boat or barge that split the current into a broad-arrowhead, at the offsets from the piers of Southwark Bridge, at the paddles of the river steamboats as they beat the filthy water, at the floating logs of timber lashed together lying off certain wharves, his shining eyes darted a hungry look. After a darkening hour or so, suddenly the rudder-lines tightened in his hold, and he steered hard towards the Surrey shore.

Always watching his face, the girl instantly answered to the action in her sculling; presently the boat swung round, quivered as from a sudden jerk, and the upper half of the man was stretched out over the stern."

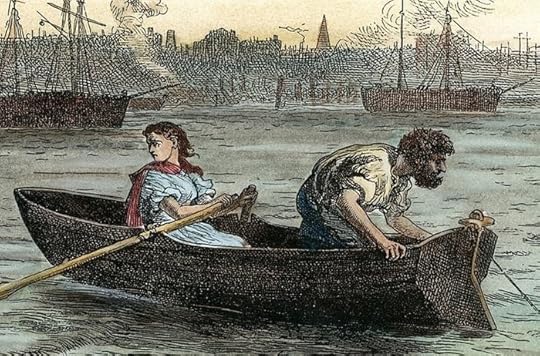

"Lizzie and Gaffer on the Thames"

James Mahoney

Chapter 1

1875

Commentary:

"The passage illustrated, with Lizzie Hexam vigorously and confidently rowing while her grizzled, bare-armed father fishes something (or someone) from the turgid Thames waters that beat about the boat, occurs immediately below the wood-cut. The square tower of Westminster Abbey is dimly discerned on the skyline, and a large barge immediately behind the figures establishes the setting as the industrial section of the river. "She watched his face as earnestly as he watched the river" in the text, but in the plate she studies the river, alert to its variable currents, a pose indicative of her skill at the oar and as a navigator of those treacherous waters, her left fore-arm as powerful as the more sinewy forearms of her father. Thus, Mahoney depicts her unladylike skill and knowledge, and imbues her gaze with the "business-like usage" of her father's."

Sol Eytinge Jr.

"Originally illustrated for the Chapman and Hall serialisation by Marcus Stone, who enjoyed Dickens's complete confidence and a considerable degree of autonomy in planning an extensive narrative-pictorial program (from May 1864 through November 1865), Our Mutual Friend was published in the United States in the "Illustrated Household Edition" of 1870 as a joint venture by a Boston and a New York publisher. The artist whom they selected for the project, Solomon Eytinge, Junior (1833-1905), had already illustrated A Holiday Romance for Ticknor-Fields' juvenile magazine Our Young Folks in 1867. Moreover and more significantly, in anticipation of that 1867-68 reading tour, the Boston publisher James T. Fields had commissioned from Eytinge ninety-six designs for wood-engravings to grace the pages of the exhaustive Diamond Edition of Dickens's works. In May, 1869, which marked the beginning of the last year of the novelist's life, Eytinge in company with James and Annie Fields, and her friend Amy Lowell, travelled to England and visited Dickens and his family at Gad's Hill, near Rochester, Kent, where over several siitings he painted the writer's portrait, which he subsequently transformed in to a lithograph to be published by Ticknor-Fields.

Some of the following plates eschew the conventional framed form of nineteenth-century book illustration by using a a rounded arch for the upper register of each picture, which is generally a double character study rather than an attempt to capture an actual moment in the text. William Winter in his autobiography recalls that Eytinge's illustrations for Dickens's works "gained the emphatic approval of the novelist", although of course the pair did not actively collaborate on this series, as did Marcus Stone and Dickens for the 1864-65 forty serial illustrations for Chapman and Hall. Nevertheless, as one regards this series of sixteen dual character studies for Our Mutual Friend, one is tempted to agree with Winter that the most appropriate pictures that have been made for illustration of the novels of Dickens, — pictures that are truly representative and free from the element of caricature, — are those made by Eytinge. .

The Bird Of Prey

Chapter 1

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

1870 Illustrated Household Edition

Commentary:

"Sol Eytinge, Ticknor-Fields' house illustrator who completed all of the plates for the Diamond Edition, met Dickens over dinner in the Parker House, Boston, at the start of the great writer's second American reading tour in 1867. Eytinge at that time completed four thumbnails (embellished initial-letter vignettes) for the Our Young Folks serialisation of the four-part Dickens children's story "A Holiday Romance." At Dickens's death in 1870, Chapman and Hall decided to issue the entire sequence of Dickens's novels and novels in a large-scale format and illustrated by contemporary artists in what it called "The Household Edition." Given the fluidity of American copyright in that era, it should have come as no surprise that the Household Edition would be imitated across the Atlantic as "The Illustrated Household Edition" by a consortium of New York and Boston publishers, with plates by gifted American illustrator Sol Eytinge, Jr., to lend the venture legitimacy — and secure American copyright. The initial woodcut sets the tone for the work; rather than capturing a moment in the action, apparently Eytinge's intention was the provide the first in a series of sixteen character studies in a quasi-realistic manner that both looks back to the caricatures of Hablot Knight Browne and forward to the thorough-going realism of Fred Barnard, lead illustrator for Chapman and Hall's forthcoming Household Edition. Lizzie Hexam is the reluctant companion and helper of her father, the Thames waterman Gaffer Hexam, who preys upon the victims of the polluted river."

If Fred Barnard illustrated this novel I haven't found him yet.

"Originally illustrated for the Chapman and Hall serialisation by Marcus Stone, who enjoyed Dickens's complete confidence and a considerable degree of autonomy in planning an extensive narrative-pictorial program (from May 1864 through November 1865), Our Mutual Friend was published in the United States in the "Illustrated Household Edition" of 1870 as a joint venture by a Boston and a New York publisher. The artist whom they selected for the project, Solomon Eytinge, Junior (1833-1905), had already illustrated A Holiday Romance for Ticknor-Fields' juvenile magazine Our Young Folks in 1867. Moreover and more significantly, in anticipation of that 1867-68 reading tour, the Boston publisher James T. Fields had commissioned from Eytinge ninety-six designs for wood-engravings to grace the pages of the exhaustive Diamond Edition of Dickens's works. In May, 1869, which marked the beginning of the last year of the novelist's life, Eytinge in company with James and Annie Fields, and her friend Amy Lowell, travelled to England and visited Dickens and his family at Gad's Hill, near Rochester, Kent, where over several siitings he painted the writer's portrait, which he subsequently transformed in to a lithograph to be published by Ticknor-Fields.

Some of the following plates eschew the conventional framed form of nineteenth-century book illustration by using a a rounded arch for the upper register of each picture, which is generally a double character study rather than an attempt to capture an actual moment in the text. William Winter in his autobiography recalls that Eytinge's illustrations for Dickens's works "gained the emphatic approval of the novelist", although of course the pair did not actively collaborate on this series, as did Marcus Stone and Dickens for the 1864-65 forty serial illustrations for Chapman and Hall. Nevertheless, as one regards this series of sixteen dual character studies for Our Mutual Friend, one is tempted to agree with Winter that the most appropriate pictures that have been made for illustration of the novels of Dickens, — pictures that are truly representative and free from the element of caricature, — are those made by Eytinge. .

The Bird Of Prey

Chapter 1

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

1870 Illustrated Household Edition

Commentary:

"Sol Eytinge, Ticknor-Fields' house illustrator who completed all of the plates for the Diamond Edition, met Dickens over dinner in the Parker House, Boston, at the start of the great writer's second American reading tour in 1867. Eytinge at that time completed four thumbnails (embellished initial-letter vignettes) for the Our Young Folks serialisation of the four-part Dickens children's story "A Holiday Romance." At Dickens's death in 1870, Chapman and Hall decided to issue the entire sequence of Dickens's novels and novels in a large-scale format and illustrated by contemporary artists in what it called "The Household Edition." Given the fluidity of American copyright in that era, it should have come as no surprise that the Household Edition would be imitated across the Atlantic as "The Illustrated Household Edition" by a consortium of New York and Boston publishers, with plates by gifted American illustrator Sol Eytinge, Jr., to lend the venture legitimacy — and secure American copyright. The initial woodcut sets the tone for the work; rather than capturing a moment in the action, apparently Eytinge's intention was the provide the first in a series of sixteen character studies in a quasi-realistic manner that both looks back to the caricatures of Hablot Knight Browne and forward to the thorough-going realism of Fred Barnard, lead illustrator for Chapman and Hall's forthcoming Household Edition. Lizzie Hexam is the reluctant companion and helper of her father, the Thames waterman Gaffer Hexam, who preys upon the victims of the polluted river."

If Fred Barnard illustrated this novel I haven't found him yet.

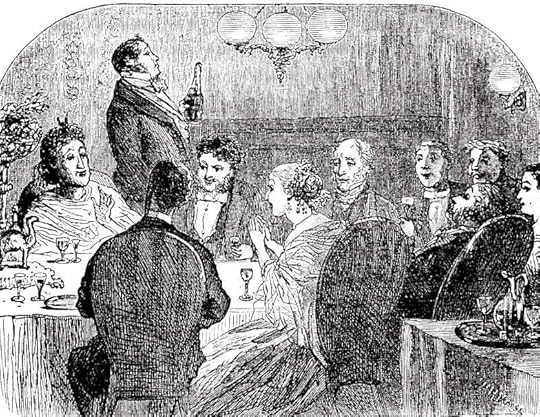

"The Veneering Dinner"

Sol Eytinge, Junior

Chapter 2

Text Illustrated:

"The great looking-glass above the sideboard, reflects the table and the company. Reflects the new Veneering crest, in gold and eke in silver, frosted and also thawed, a camel of all work. The Heralds’ College found out a Crusading ancestor for Veneering who bore a camel on his shield (or might have done it if he had thought of it), and a caravan of camels take charge of the fruits and flowers and candles, and kneel down be loaded with the salt. Reflects Veneering; forty, wavy-haired, dark, tending to corpulence, sly, mysterious, filmy—a kind of sufficiently well-looking veiled-prophet, not prophesying. Reflects Mrs Veneering; fair, aquiline-nosed and fingered, not so much light hair as she might have, gorgeous in raiment and jewels, enthusiastic, propitiatory, conscious that a corner of her husband’s veil is over herself. Reflects Podsnap; prosperously feeding, two little light-coloured wiry wings, one on either side of his else bald head, looking as like his hairbrushes as his hair, dissolving view of red beads on his forehead, large allowance of crumpled shirt-collar up behind. Reflects Mrs Podsnap; fine woman for Professor Owen, quantity of bone, neck and nostrils like a rocking-horse, hard features, majestic head-dress in which Podsnap has hung golden offerings. Reflects Twemlow; grey, dry, polite, susceptible to east wind, First-Gentleman-in-Europe collar and cravat, cheeks drawn in as if he had made a great effort to retire into himself some years ago, and had got so far and had never got any farther. Reflects mature young lady; raven locks, and complexion that lights up well when well powdered—as it is—carrying on considerably in the captivation of mature young gentleman; with too much nose in his face, too much ginger in his whiskers, too much torso in his waistcoat, too much sparkle in his studs, his eyes, his buttons, his talk, and his teeth. Reflects charming old Lady Tippins on Veneering’s right; with an immense obtuse drab oblong face, like a face in a tablespoon, and a dyed Long Walk up the top of her head, as a convenient public approach to the bunch of false hair behind, pleased to patronize Mrs Veneering opposite, who is pleased to be patronized. Reflects a certain ‘Mortimer’, another of Veneering’s oldest friends; who never was in the house before, and appears not to want to come again, who sits disconsolate on Mrs Veneering’s left, and who was inveigled by Lady Tippins (a friend of his boyhood) to come to these people’s and talk, and who won’t talk. Reflects Eugene, friend of Mortimer; buried alive in the back of his chair, behind a shoulder—with a powder-epaulette on it—of the mature young lady, and gloomily resorting to the champagne chalice whenever proffered by the Analytical Chemist. Lastly, the looking-glass reflects Boots and Brewer, and two other stuffed Buffers interposed between the rest of the company and possible accidents."

"Show us a picture," said the boy. "Tell us where to look."

James Mahoney

1875

Text Illustrated:

"Yes. Then as I sit a-looking at the fire, I seem to see in the burning coal — like where that glow is now —"

"That's gas, that is," said the boy, "coming out of a bit of a forest that's been under the mud that was under the water in the days of Noah's Ark. Look here! When I take the poker — so — and give it a dig —"

"Don't disturb it, Charley, or it'll be all in a blaze. It's that dull glow near it, coming and going, that I mean. When I look at it of an evening, it comes like pictures to me, Charley."

"Show us a picture, said the boy. Tell us where to look."

"Ah! It wants my eyes, Charley."

"Cut away then, and tell us what your eyes make of it."

"Why, there are you and me, Charley, when you were quite a baby that never knew a mother —

"Don't go saying I never knew a mother," interposed the boy, "for I knew a little sister that was sister and mother both."

The girl laughed delightedly, and here eyes filled with pleasant tears, as he put both his arms round her waist and so held her.

"There are you and me, Charley, when father was away at work and locked us out, for fear we should set ourselves afire or fall out of window, sitting on the door-sill, sitting on other door-steps, sitting on the bank of the river, wandering about to get through the time. You are rather heavy to carry, Charley, and I am often obliged to rest. Sometimes we are sleepy and fall asleep together in a corner, sometimes we are very hungry, sometimes we are a little frightened, but what is oftenest hard upon us is the cold. You remember, Charley?"

"I remember," said the boy, pressing her to him twice or thrice, "that I snuggled under a little shawl, and it was warm there."

"Sometimes it rains, and we creep under a boat or the like of that: sometimes it's dark, and we get among the gaslights, sitting watching the people as they go along the streets. At last, up comes father and takes us home. And home seems such a shelter after out of doors! And father pulls my shoes off, and dries my feet at the fire, and has me to sit by him while he smokes his pipe long after you are abed, and I notice that father's is a large hand but never a heavy one when it touches me, and that father's is a rough voice but never an angry one when it speaks to me. So, I grow up, and little by little father trusts me, and makes me his companion, and, let him be put out as he may, never once strikes me."

The listening boy gave a grunt here, as much as to say "But he strikes me, though!"

"Those are some of the pictures of what is past, Charley."

"Cut away again," said the boy, "and give us a fortune-telling one; a future one."

"Well! There am I, continuing with father and holding to father, because father loves me and I love father. I can't so much as read a book, because, if I had learned, father would have thought I was deserting him, and I should have lost my influence. I have not the influence I want to have, I cannot stop some dreadful things I try to stop, but I go on in the hope and trust that the time will come. In the meanwhile I know that I am in some things a stay to father, and that if I was not faithful to him he would--in revenge-like, or in disappointment, or both — go wild and bad."

"Give us a touch of the fortune-telling pictures about me."

"I was passing on to them, Charley," said the girl, who had not changed her attitude since she began, and who now mournfully shook her head; 'the others were all leading up. There are you — "

"Where am I, Liz?"

"Still in the hollow down by the flare."

"Witnessing the Agreement"

Chapter 4

Marcus Stone

1865

Text Illustrated:

"Two or three times during this short address, the cherub addressed had made chubby motions towards a chair. The gentleman now took it, laying a hesitating hand on a corner of the table, and with another hesitating hand lifting the crown of his hat to his lips, and drawing it before his mouth.

‘The gentleman, R. W.,’ said Mrs Wilfer, ‘proposes to take your apartments by the quarter. A quarter’s notice on either side.’

‘Shall I mention, sir,’ insinuated the landlord, expecting it to be received as a matter of course, ‘the form of a reference?’

‘I think,’ returned the gentleman, after a pause, ‘that a reference is not necessary; neither, to say the truth, is it convenient, for I am a stranger in London. I require no reference from you, and perhaps, therefore, you will require none from me. That will be fair on both sides. Indeed, I show the greater confidence of the two, for I will pay in advance whatever you please, and I am going to trust my furniture here. Whereas, if you were in embarrassed circumstances—this is merely supposititious—’

Conscience causing R. Wilfer to colour, Mrs Wilfer, from a corner (she always got into stately corners) came to the rescue with a deep-toned ‘Per-fectly.’

‘—Why then I—might lose it.’

‘Well!’ observed R. Wilfer, cheerfully, ‘money and goods are certainly the best of references.’

‘Do you think they are the best, pa?’ asked Miss Bella, in a low voice, and without looking over her shoulder as she warmed her foot on the fender.

‘Among the best, my dear.’

‘I should have thought, myself, it was so easy to add the usual kind of one,’ said Bella, with a toss of her curls."

Commentary:

"The passage illustrated, with Lizzie Hexam showing her younger brother, Charley, the pictures in the fire recalls similar scenes elsewhere in Dickens, notably in The Haunted Man (1848). The passage occurs in Chapter 3, "Another Man," in Harper and Brothers edition, positioned near the passage dealing with the older sister as surrogate mother and the motherless boy close; the picture is positioned in the Chapman and Hall edition in the following chapter ("The R. Wilfer Family,").

The brazier in this scene, throwing the sideboards and plates into shadowy dimness, is identical to the one in the title-page vignette, and therefore provides visual continuity between the two scenes. Symbolically, it is the working-class equivalent of the middle-class hearth, the center of the family's communal activity. Mahoney uses the working class family's mutual tenderness and concern to foil the next scene, in which the money-focused, middle-class Bella signs her father's rental agreement as a witness, a legal document that opens the middle-class home to a total stranger, albeit one of respectable social status, the enigmatic John Rokesmith."

"When it came to Bella's turn to sign her name, Mr. Rokesmith, who was standing, as he had sat, with a hesitating hand upon the table, looked at her stealthily but narrowly."

James Mahoney

1875

Commentary:

"The passage illustrated, with Bella studiously appending her name to her father's rental agreement in duplicate with John Rokesmith, occurs in the Wilfers' parlour in the Holloway region north of London, an unsavoury and decidedly unrespectable district where one would not expect to find such a family. The young middle-class adults Bella Wilfer (left) and John Rokesmith (right) dominate the scene, but also present are the "Cherub" (R. Wilfer), Bella's father, seated (centre), and, immediately behind Bella her mother and younger sister, Lavinia. Significantly, our first sight of Bella in the narrative-pictorial sequence involves her signing a legal document and participating in a commercial transaction. Bella is in mourning for a fiance she never met, "a kind of widow who never was married". Assisting her parents in concluding their quarter-term rental agreement for eight guineas with the handsome youth, Bella witnesses the document:

When it came to Bella's turn to sign her name, Mr. Rokesmith, who was standing, as he had sat, with a hesitating hand upon the table, looked at her stealthily but narrowly. He looked at the pretty figure bending down over the paper and saying, "Where am I to go, pa? Here, in this corner?"

However, Mahoney's illustration supplements the textual description of Bella's staccato, moment by moment impressions of the new tenant and Dickens's earlier description of the renter as a dark gentleman. Thirty at the utmost. An expressive, one might say handsome, face. A very bad manner. In the last degree constrained, reserved, diffident, troubled. His eyes were on Miss Bella for an instant. . . .

With the latter moment in the transaction Mahoney has assimilated the initial evaluation of Rokesmith's personality and provided appropriate details of the young man's dress and posture."

Here is the illustration by Marcus Stone "The Bird of Prey" in color. Why it's in color I don't know.

After three chapters, well, getting through with three, is there a character that is likable yet? Maybe Lizzie?

After three chapters, well, getting through with three, is there a character that is likable yet? Maybe Lizzie? Not sure if "likable" is what I'm after, but a character to likely latch on to for the rest of the story?

It does not seem like the narrative wants to shape up that way.

Kim wrote: "Here is the illustration by Marcus Stone "The Bird of Prey" in color. Why it's in color I don't know.

Kim wrote: "Here is the illustration by Marcus Stone "The Bird of Prey" in color. Why it's in color I don't know."

Kim, I've been anticipating these illustrations...mostly to put my mind at ease with what I imagined while reading. Lizzie and Gaffer in the boat, their proximity to one another is so much more intimate than what I thought. I remember there was nothing to the scull, but this seems smaller than what I imagined. Putting it in perspective now, John Harmon's body must have been in Lizzie's lap considering the size of the boat?

I like the Mahoney version of the Wilfur family and the "enigmatic John Rokeforth." Mr. Wilfur's cherubic face, Bella's sharp features and Mr. Rokeforth's dark features, can all easily be seen in perfect detail.

John wrote: "After three chapters, well, getting through with three, is there a character that is likable yet? Maybe Lizzie?

John wrote: "After three chapters, well, getting through with three, is there a character that is likable yet? Maybe Lizzie? Not sure if "likable" is what I'm after, but a character to likely latch on to for ..."

I'm not attached to any one character, as of yet; however, I am quite intrigued by Lizzie, Mr. Wilfur, and now John Rokeforth.

Any clue as to who the mutual friend is, I don't have a doubt we've already been introduced to him?

I just finished the fourth chapter today, and, as always, am in awe of Dickens' satirical pen. The first chapter, with its air of mystery and sense of horrors to come, reminded me greatly of "The Mail" in TOTC. I feel for poor Lizzie--she has evidently been engaged in retrieving dead bodies for most of her life and has been horrified by it the entire time.

I just finished the fourth chapter today, and, as always, am in awe of Dickens' satirical pen. The first chapter, with its air of mystery and sense of horrors to come, reminded me greatly of "The Mail" in TOTC. I feel for poor Lizzie--she has evidently been engaged in retrieving dead bodies for most of her life and has been horrified by it the entire time. I was much struck by the falsity of everyone at the Veneerings' party. Dickens gives us the whole scenario of Mr. and Mrs. Podsnap, who are such good friends of the Veneerings that Mr. Podsnap mistakes Twemlow for his host--a faux pas that succeeds in insulting all involved. This mistake is finally sorted out, but on the next page, Twemlow notices "Veneering and the large man linked together as twin brothers in the back drawing-room near the conservatory door, and through his ears informing him in the tones of Mrs. Veneering that the same large man is to be baby's godfather," (10). The Podsnaps have gone, in the space of a few minutes, from not even well-acquainted enough to recognize Mr. Veneering, to being the godfather of his child! There are others mentioned as "old friends" who have never been in the house before, and of course, there is Lady Tippins, an extremely unattractive-sounding woman who fancies herself surrounded by men seeking her favor. Even poor old Twemlow sounds as though he's not too fond of the Veneerings himself, but continues to show up for their dinners. I love Dickens' use of parallelism in this section. He's a master of construction!

Dickens' description of Reginald Wilfer's cherubic countenance brought a smile to my face: "So boyish was he in his curves and proportions, that his old schoolmaster meeting him in Cheapside, might have been unable to withstand the temptation of caning him on the spot," (31-2). I thought Tristram's observation that old Mr. Harmon might have chosen Bella for his son for the very reason that she is a brat very interesting. I hadn't thought of it from that angle before, but it would be a way of ensuring a lifetime of misery for him!

Kim wrote: ""The Bird of Prey"

Marcus Stone

1864

Text Illustrated:

"The figures in this boat were those of a strong man with ragged grizzled hair and a sun-browned face, and a dark girl of nineteen or tw..."

Kim. Well, you know... thanks

At the risk of having anyone think that I like the illustrations of Lizzie and her father solely because he is referred to as a "bird of prey" let me assure you that is not true. I do, however, find the "Gaffer -Lizzie" illustrations to be quite engaging.

Perhaps it is because we get to see how various illustrators approached the same subject. As noted, Dickens was much more hands-off with Stone. The other subsequent illustrations shape themselves around a small boat, a darkened sky, and a mysterious unseen object that is occupying Gaffer's attention off the stern of the boat.

The water scenes naturally present us with sailing vessels in the background. Such ships' masts have a shape similar to a cross. Gaffer's business is an unholy one. The James Mahoney illustration's commentary points out that the "square tower of Westminster Abbey is dimly discerned on the skyline." To that I would add the fact that a cross appears on the top left of the picture behind the barge. I like the Mahoney Thames-Gaffer illustration the best.

Marcus Stone

1864

Text Illustrated:

"The figures in this boat were those of a strong man with ragged grizzled hair and a sun-browned face, and a dark girl of nineteen or tw..."

Kim. Well, you know... thanks

At the risk of having anyone think that I like the illustrations of Lizzie and her father solely because he is referred to as a "bird of prey" let me assure you that is not true. I do, however, find the "Gaffer -Lizzie" illustrations to be quite engaging.

Perhaps it is because we get to see how various illustrators approached the same subject. As noted, Dickens was much more hands-off with Stone. The other subsequent illustrations shape themselves around a small boat, a darkened sky, and a mysterious unseen object that is occupying Gaffer's attention off the stern of the boat.

The water scenes naturally present us with sailing vessels in the background. Such ships' masts have a shape similar to a cross. Gaffer's business is an unholy one. The James Mahoney illustration's commentary points out that the "square tower of Westminster Abbey is dimly discerned on the skyline." To that I would add the fact that a cross appears on the top left of the picture behind the barge. I like the Mahoney Thames-Gaffer illustration the best.

Kim wrote: ""When it came to Bella's turn to sign her name, Mr. Rokesmith, who was standing, as he had sat, with a hesitating hand upon the table, looked at her stealthily but narrowly."

James Mahoney

1875

..."

For me the Bella-Rokesmith illustration is very suggestive. Bella and Rokesmith are the only two characters to be fully realized in the illustration. The others form a shadowy background. The prominence of these two characters is also developed in the look of intensity on the faces of both Bella and Rokesmith. He looks with full attention at her, not her hand that is signing the document. She has her full attention to her own signature going on the paper. It is Bella that is signing the paper and the commentary reminds us that she has been contracted out before.

This picture portends much that might occur. When Bella says "Where am I to go, Pa. Here, in this corner?" I feel a Dickensian moment is upon us. While Bella may be referring to her signature on the rental agreement, she may also be referring to her physical self.

I feel Bella and Lizzie will move us forward in the novel and are characters to follow closely.

James Mahoney

1875

..."

For me the Bella-Rokesmith illustration is very suggestive. Bella and Rokesmith are the only two characters to be fully realized in the illustration. The others form a shadowy background. The prominence of these two characters is also developed in the look of intensity on the faces of both Bella and Rokesmith. He looks with full attention at her, not her hand that is signing the document. She has her full attention to her own signature going on the paper. It is Bella that is signing the paper and the commentary reminds us that she has been contracted out before.

This picture portends much that might occur. When Bella says "Where am I to go, Pa. Here, in this corner?" I feel a Dickensian moment is upon us. While Bella may be referring to her signature on the rental agreement, she may also be referring to her physical self.

I feel Bella and Lizzie will move us forward in the novel and are characters to follow closely.

Cindy wrote: "I just finished the fourth chapter today, and, as always, am in awe of Dickens' satirical pen. The first chapter, with its air of mystery and sense of horrors to come, reminded me greatly of "The M..."

Hi Cindy

To step into the 20C fo a moment I'm wondering if F. Scott Fitzgerald was at all influenced by this chapter. In The Great Gatsby, Jay Gatsby had a party where no one really knew each other either. There is also a scene at the party where a person expresses his amazement with Gatsby's library, not only because of its impressive nature, but because of the fact that none of the books' pages are cut. Clearly, both Veneering and Gatsby shared the belief that an impressive library was meant to speak for its owner.

Hi Cindy

To step into the 20C fo a moment I'm wondering if F. Scott Fitzgerald was at all influenced by this chapter. In The Great Gatsby, Jay Gatsby had a party where no one really knew each other either. There is also a scene at the party where a person expresses his amazement with Gatsby's library, not only because of its impressive nature, but because of the fact that none of the books' pages are cut. Clearly, both Veneering and Gatsby shared the belief that an impressive library was meant to speak for its owner.

Peter wrote: "Cindy wrote: "I just finished the fourth chapter today, and, as always, am in awe of Dickens' satirical pen. The first chapter, with its air of mystery and sense of horrors to come, reminded me gre..."

Peter wrote: "Cindy wrote: "I just finished the fourth chapter today, and, as always, am in awe of Dickens' satirical pen. The first chapter, with its air of mystery and sense of horrors to come, reminded me gre..."I thought of Gatsby's library when I read that! I would not be surprised if that had inspired Fitzgerald; there are many similarities. Like you said, Gatsby is also offering hospitality to people who can stand right next to him and not recognize him, just as with Mr. Veneering. Gatsby's entire persona is a veneer, albeit an expensive one. Owl-Eyes is impressed by the fact that, given that the library is merely an affectation, that Gatsby went to the trouble of having real books--but they might as well be facades, given their unread state. The difference, I think, is that Gatsby is by-and-large unconcerned with the people at his parties. They are just as much props as the books in the library. He doesn't pretend to know them any more than they know him. The Veneerings, however, seem to want to present themselves as having intimate friendships with people they don't know. I mean, I just met them myself, but that's how they come across.

Cindy wrote: "Peter wrote: "Cindy wrote: "I just finished the fourth chapter today, and, as always, am in awe of Dickens' satirical pen. The first chapter, with its air of mystery and sense of horrors to come, r..."

Cindy

Yes. Gatsby's specific reason for his parties was to attract Daisy whereas the Veneerings were glad to attract anyone and everyone.

It will be interesting to see if any other echoes emerge that will link the two novels. Candidly, I do not know that much about Fitzgerald or the extent to which he could have been influenced by his reading of Dickens.

Cindy

Yes. Gatsby's specific reason for his parties was to attract Daisy whereas the Veneerings were glad to attract anyone and everyone.

It will be interesting to see if any other echoes emerge that will link the two novels. Candidly, I do not know that much about Fitzgerald or the extent to which he could have been influenced by his reading of Dickens.

Cindy wrote: "I thought Tristram's observation that old Mr. Harmon might have chosen Bella for his son for the very reason that she is a brat very interesting."

It struck me because it takes one to know one, Cindy. I'll give you one example: Since my sister has always been keen on order, silence, manners and all that, I made it a point, when buying a present for her children - who were quite small at that time - that it would always be a toy, and that the toy in question would always invite her children to be noisy, extremely noisy by playing repetetive and inane tunes, for instance. My godson once got a wonderful tin drum from me, and at another time a hobbyhorse, which not only encouraged him to run around in the living-room but which also imitated the clatter of hooves and the neigh of a horse. And I invariably told the children to enjoy themselves.

It struck me because it takes one to know one, Cindy. I'll give you one example: Since my sister has always been keen on order, silence, manners and all that, I made it a point, when buying a present for her children - who were quite small at that time - that it would always be a toy, and that the toy in question would always invite her children to be noisy, extremely noisy by playing repetetive and inane tunes, for instance. My godson once got a wonderful tin drum from me, and at another time a hobbyhorse, which not only encouraged him to run around in the living-room but which also imitated the clatter of hooves and the neigh of a horse. And I invariably told the children to enjoy themselves.

Kim,

I found your introduction about the collaboration between Dickens and Stone very interesting. Then a question occurred to me: I wonder whether the illustrators already knew how the story would go on and how it would end. Would they not need that knowledge in order to make intelligent choices as to which scenes to pick for an illustration? Not only in the sense of picking the most important moments of a story but also in order to highlight details that might prove of importance later on? And did they regard their work as a feat of art in itself, or was it just a job for them which helped profile the superior (?) art of Charles Dickens?

I found your introduction about the collaboration between Dickens and Stone very interesting. Then a question occurred to me: I wonder whether the illustrators already knew how the story would go on and how it would end. Would they not need that knowledge in order to make intelligent choices as to which scenes to pick for an illustration? Not only in the sense of picking the most important moments of a story but also in order to highlight details that might prove of importance later on? And did they regard their work as a feat of art in itself, or was it just a job for them which helped profile the superior (?) art of Charles Dickens?

At the moment, I, too, find it hard to "like" any of the characters given us up to now. Twemlow is somewhat likeable because of his predicament to make sense of the society he finds himself thrown in with but then he remains very sketchy as a character and soon withdraws into the background to make room for Mortimer and Eugene.

As to Lizzie and Bella, Lizzie strikes me as the typical Dickens heroine: forbearing, loving, self-denying and altogether uninteresting. Bella, however, is not really likeable at all, even though her moody sallies seem to be tempered by her love for her father. However when she finally started doing her father's hair, I really cringed. Nevertheless, her situation is quite interesting: She is forced to wear mourning for a man whom she never met, and her plans of escaping the poverty of the family circle are thwarted at the moment.

As to Lizzie and Bella, Lizzie strikes me as the typical Dickens heroine: forbearing, loving, self-denying and altogether uninteresting. Bella, however, is not really likeable at all, even though her moody sallies seem to be tempered by her love for her father. However when she finally started doing her father's hair, I really cringed. Nevertheless, her situation is quite interesting: She is forced to wear mourning for a man whom she never met, and her plans of escaping the poverty of the family circle are thwarted at the moment.

Tristram wrote: "At the moment, I, too, find it hard to "like" any of the characters given us up to now. Twemlow is somewhat likeable because of his predicament to make sense of the society he finds himself thrown ..."

Tristram wrote: "At the moment, I, too, find it hard to "like" any of the characters given us up to now. Twemlow is somewhat likeable because of his predicament to make sense of the society he finds himself thrown ..."However when she finally started doing her father's hair, I really cringed.

Ha! And she fixes it with a fork, no less... Yes? Sorry to dredge up the cringeworthy moment, Tristram ;)

Tristram wrote: "Cindy wrote: "I thought Tristram's observation that old Mr. Harmon might have chosen Bella for his son for the very reason that she is a brat very interesting."

Tristram wrote: "Cindy wrote: "I thought Tristram's observation that old Mr. Harmon might have chosen Bella for his son for the very reason that she is a brat very interesting."It struck me because it takes one t..."

That's awesome! I can just imagine your sister's chagrin, and only hope your gifts were not whisked away as soon as you car turned the corner. I doubt she appreciates your humor, but I have found that the best jests are those that require diabolical plotting, a soupçon of wickedness, wouldn't you agree?

Tristram wrote: "Kim,

I found your introduction about the collaboration between Dickens and Stone very interesting. Then a question occurred to me: I wonder whether the illustrators already knew how the story woul..."

Hi Tristram

Kim references Kitton's 1899 book Dickens and his Illustrators. I have this book which can be ordered in a reprint version from Amazon. It is a great introduction to the magical world of Dickens's illustrators. Kitton is an enthusiast so one needs to dial his energy back a bit, but it is a grand read.

I found your introduction about the collaboration between Dickens and Stone very interesting. Then a question occurred to me: I wonder whether the illustrators already knew how the story woul..."

Hi Tristram

Kim references Kitton's 1899 book Dickens and his Illustrators. I have this book which can be ordered in a reprint version from Amazon. It is a great introduction to the magical world of Dickens's illustrators. Kitton is an enthusiast so one needs to dial his energy back a bit, but it is a grand read.

Peter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Okay then, let's have the other three Chapters for this week:

Peter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Okay then, let's have the other three Chapters for this week:The second Chapter, „The Man from Somewhere“, starts on a completely different note, namely a clearly satirical one. ..."

Your comment just made me think "mystery". We have a will, a dead body...we even have the "crime scene"-- the outline of a body in the boat. Dickens wrote OMF six years after Arthur Conan Doyle was born...and three years before Collins' Moonstone, considered the first mystery novel.

Peter wrote: "LindaH wrote: "Re chapter 2

Peter wrote: "LindaH wrote: "Re chapter 2I admit I didn't follow the characters in the Looking Glass paragraph the first read, and after several rereads, I still find it tricky and have a few questions:

What ..."

Hi Peter

I will always think of Mrs Tippins' fun-house face now...thanks.

John wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Okay then, let's have the other three Chapters for this week:

John wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Okay then, let's have the other three Chapters for this week:The second Chapter, „The Man from Somewhere“, starts on a completely different note, namely a clearly satirical one. ..."

Ha-ha. Exactly! Love the text.

John wrote: "Ami wrote: "John wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Okay then, let's have the other three Chapters for this week:

John wrote: "Ami wrote: "John wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Okay then, let's have the other three Chapters for this week:The second Chapter, „The Man from Somewhere“, starts on a completely different note, namely ..."

Thanks, Ami, for pointing out Tremlow’s distance from the host at the table related to his confusion to his status . I didn't get that.

Tristram wrote: "John wrote: "and I was still unsure whether Twemlow was a human being or a piece of furniture."

Tristram wrote: "John wrote: "and I was still unsure whether Twemlow was a human being or a piece of furniture."I'd rather see that as testimony to how brilliantly Dickens describes the scene here, i.e. showing h..."

Of course! Veneering is veiled to look like someone he is not. Both Veneering s are presenting illusions, ... as a dancer does with veils?

I thought I'd read this book before, but having now read the first 4 chapters, I realise I would not have forgotten that first scene! So I'm excited to explore this novel.

I thought I'd read this book before, but having now read the first 4 chapters, I realise I would not have forgotten that first scene! So I'm excited to explore this novel.I always enjoy how Dickens switches between the horrific and the comedic and back again. Poor Twemlow made me smile. Then Lizzie paints such a pitiful picture of her upbringing. Such a switch of emotions.

Tristram wrote: "At the moment, I, too, find it hard to "like" any of the characters ..."

Tristram wrote: "At the moment, I, too, find it hard to "like" any of the characters ..."I like Charley, he seems optimistic and determined to make something of himself. Agree Lizzie seems to be that standard Dickens 'angel' girl.

I believe it was John who mentioned that he was unsure whether Twemlow is a person or a piece of furniture. I too was and am confused. During the first part of the chapter I was convinced that he was a dining table - an anthropomorphic Dickensian sleight of hand. Then I came to believe that he had to be, as was Pinocchio at last, 'a real boy'. I am stumped!

I believe it was John who mentioned that he was unsure whether Twemlow is a person or a piece of furniture. I too was and am confused. During the first part of the chapter I was convinced that he was a dining table - an anthropomorphic Dickensian sleight of hand. Then I came to believe that he had to be, as was Pinocchio at last, 'a real boy'. I am stumped!

Tristram and Ami, the fork as an implement for hairdressing grossed me out. Why a fork? Were the prongs used as a comb? This is certainly quite grotesque.

Tristram and Ami, the fork as an implement for hairdressing grossed me out. Why a fork? Were the prongs used as a comb? This is certainly quite grotesque.

Hilary wrote: "I believe it was John who mentioned that he was unsure whether Twemlow is a person or a piece of furniture. I too was and am confused. During the first part of the chapter I was convinced that he w..."

Hilary wrote: "I believe it was John who mentioned that he was unsure whether Twemlow is a person or a piece of furniture. I too was and am confused. During the first part of the chapter I was convinced that he w..."Yes, that was me.

And I don't know how to feel about it exactly, but I read the beginning paragraphs of that chapter several times and still came away that it was a section of furniture I was dealing with.

Hilary wrote: "Yes exactly, John! I don't quite get it. No 'quite' about it. I don't at all get it!"

Hilary wrote: "Yes exactly, John! I don't quite get it. No 'quite' about it. I don't at all get it!"Lol. I'm going back again in a few minutes and trying those paragraphs again. I figure when I have furniture right, I will have people right.

Just so I am clear -- today marks completion of Chapters 1-4 based on schedule?

You guys are prolific and impressive. I am learning a lot. Chapter one was sinister. Chapter two is a juxtaposition to it in the form of the darkness of the river as opposed to the brightness of the "bran-new" Veneerings. I love that euphemism.

You guys are prolific and impressive. I am learning a lot. Chapter one was sinister. Chapter two is a juxtaposition to it in the form of the darkness of the river as opposed to the brightness of the "bran-new" Veneerings. I love that euphemism. I read somewhere that this chapter is renowned in literature circles for it's characterization.

Hilary wrote: "Tristram and Ami, the fork as an implement for hairdressing grossed me out. Why a fork? Were the prongs used as a comb? This is certainly quite grotesque."

Hilary wrote: "Tristram and Ami, the fork as an implement for hairdressing grossed me out. Why a fork? Were the prongs used as a comb? This is certainly quite grotesque."Hilary, this one's for you! :P

Ariel's Dinglehopper from Disney's, The Little Mermaid

Cindy wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Cindy wrote: "I thought Tristram's observation that old Mr. Harmon might have chosen Bella for his son for the very reason that she is a brat very interesting."

It struck me becau..."

Of course, I made sure that my nephew and niece started playing with the noisy toys when I was still there. This way they got endeared to them (for whatever spell of time a modern child's endearment to a toy lasts), and so my sister could not just get rid of the toys. And yes, I would agree to your definition of the best jests, whereas my sister probably wouldn't ;-)

It struck me becau..."

Of course, I made sure that my nephew and niece started playing with the noisy toys when I was still there. This way they got endeared to them (for whatever spell of time a modern child's endearment to a toy lasts), and so my sister could not just get rid of the toys. And yes, I would agree to your definition of the best jests, whereas my sister probably wouldn't ;-)

Peter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Kim,

I found your introduction about the collaboration between Dickens and Stone very interesting. Then a question occurred to me: I wonder whether the illustrators already knew h..."

I think you wrote a review on this book, didn't you? You also mentioned it in one of our recent discussions as full of insights but as not really having good-quality renditions of the illustrations?

I found your introduction about the collaboration between Dickens and Stone very interesting. Then a question occurred to me: I wonder whether the illustrators already knew h..."

I think you wrote a review on this book, didn't you? You also mentioned it in one of our recent discussions as full of insights but as not really having good-quality renditions of the illustrations?

John wrote: "Just so I am clear -- today marks completion of Chapters 1-4 based on schedule?"

Yes, it does. The thread for the next few chapters will be opened on Sunday, but you can, of course, always add comments on earlier chapters because the preceding threads won't be closed. This way, you needn't feel obliged to rush through the novel but have all the time in the world to enjoy it.

Yes, it does. The thread for the next few chapters will be opened on Sunday, but you can, of course, always add comments on earlier chapters because the preceding threads won't be closed. This way, you needn't feel obliged to rush through the novel but have all the time in the world to enjoy it.

Hilary wrote: "Tristram and Ami, the fork as an implement for hairdressing grossed me out. Why a fork? Were the prongs used as a comb? This is certainly quite grotesque."

I remember having repeatedly used a fork as a comb, too, but up to now I've never used a comb as a fork.

I remember having repeatedly used a fork as a comb, too, but up to now I've never used a comb as a fork.

Pamela wrote: "Tristram wrote: "At the moment, I, too, find it hard to "like" any of the characters ..."

I like Charley, he seems optimistic and determined to make something of himself. Agree Lizzie seems to be ..."

You're right: Charley strikes one as a person determined to make the best out of life, instead of just feeling sorry for himself - as Eugene and, to a lesser extent, Mortimer do when they seem to be vying for the title of the most luckless lawyer. Life has not been to good for Charley, considering that his father has no understanding for his ambition and that he even has to hide his skills - mark, however, that Lizzie is making a greater sacrifice in that she sets money aside to make it look as though it were earned by her brother. All in all, Charley is well aware of the fact that his sister is his father's favourite, and all this may lead to an estrangement within the family circle.

What gives me trouble, though, about Charley is that he is described as neither really civilized nor savage.

I like Charley, he seems optimistic and determined to make something of himself. Agree Lizzie seems to be ..."

You're right: Charley strikes one as a person determined to make the best out of life, instead of just feeling sorry for himself - as Eugene and, to a lesser extent, Mortimer do when they seem to be vying for the title of the most luckless lawyer. Life has not been to good for Charley, considering that his father has no understanding for his ambition and that he even has to hide his skills - mark, however, that Lizzie is making a greater sacrifice in that she sets money aside to make it look as though it were earned by her brother. All in all, Charley is well aware of the fact that his sister is his father's favourite, and all this may lead to an estrangement within the family circle.

What gives me trouble, though, about Charley is that he is described as neither really civilized nor savage.

Tristram wrote: "Pamela wrote: "Tristram wrote: "At the moment, I, too, find it hard to "like" any of the characters ..."

Tristram wrote: "Pamela wrote: "Tristram wrote: "At the moment, I, too, find it hard to "like" any of the characters ..."I like Charley, he seems optimistic and determined to make something of himself. Agree Lizz..."

Tristam, I have a question that involves OMF but also the Dickens canon. I am curious -- is there a particular novel that is populated with the most characters, by far, or even close? And if so, is it OMF? I am struck by the sheer number of characters in OMF after four chapters.

Books mentioned in this topic

Heart of Darkness (other topics)Dirty Old London: The Victorian Fight Against Filth (other topics)

Martin Chuzzlewit (other topics)

Dirty Old London: The Victorian Fight Against Filth (other topics)

Bleak House (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

John Sutherland (other topics)Edgar Allan Poe (other topics)

From everything I've read through the years, most literary reviewers believe Bleak House was his best. I think of people like Harold Bloom and Charles Van Doren and others. It does seem ..."

OMF is a challenge I'm willing to accept because for me it ranks among the finest Dickens novels. It's my second favourite after BH, my third being, and I know that this might be an unusual choice, Martin Chuzzlewit because it has my favourite Dickens character in it. Mine and Mrs. Harris's, that is!