The Pickwick Club discussion

Little Dorrit

>

Book II Chapters 05 - 07

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Chapter 6 is titled "Something Right Somewhere" and so I am looking forward to pleasant things happening in the chapter but it doesn't look good. We start with Henry Gowan "loitering moodily about on neutral ground". Henry is in the habit "of seeking some sort of recompense in the discontented boast of being disappointed." Poor Henry, he declares that all art is "trash" and that he turns out nothing else. He makes it a practice to show he is poor and by that to show that he should be rich. He would publicly discuss the Barnacles so that everyone would be aware of his connection to them and makes it known that he had married against the wishes of his family and has married beneath his station.

Chapter 6 is titled "Something Right Somewhere" and so I am looking forward to pleasant things happening in the chapter but it doesn't look good. We start with Henry Gowan "loitering moodily about on neutral ground". Henry is in the habit "of seeking some sort of recompense in the discontented boast of being disappointed." Poor Henry, he declares that all art is "trash" and that he turns out nothing else. He makes it a practice to show he is poor and by that to show that he should be rich. He would publicly discuss the Barnacles so that everyone would be aware of his connection to them and makes it known that he had married against the wishes of his family and has married beneath his station. "Monsieur Blandois of Paris" has accompanied them to Venice and spends much of his time with Mr. Gowan. Mr. Gowan had been deciding whether he liked or disliked Blandois when they met him in Geneva, not being able to decide whether to "kick him or encourage him." Minnie expressed a definite dislike of the man, and so Henry decided to befriend him. He wanted to assert his independence after her father paid his debts and he likes setting up Blandois as the type of elegance, and making him a satire upon others. He doesn't care for him and if he had any reason to throw him out the window he would, but for now he is his almost constant companion.

When Amy makes her visit to Mrs. Gowan unfortunately Fanny insists on coming along. I mean unfortunately for Amy and Pet that is. Fanny does the initial talking, mentioning how she heard that the Gowans knew the Merdles. Pet says they are Henry’s friends whom she has not yet met. Fanny feels superior in having met Mrs. Merdle saying that she thinks Pet will like Mrs. Merdle and that the Dorrits and Merdles are quite good friends. Pet takes Amy and Fanny into Henry's studio where they find Henry at work painting a portrait and Blandois also present being the model for the painting. Blandois seems very uneasy when Henry describes the painting to the ladies:

'Let the ladies at least see the original of the daub, that they may know what it's meant for. There he stands, you see. A bravo waiting for his prey, a distinguished noble waiting to save his country, the common enemy waiting to do somebody a bad turn, an angelic messenger waiting to do somebody a good turn—whatever you think he looks most like!'

'Say, Professore Mio, a poor gentleman waiting to do homage to elegance and beauty,' remarked Blandois.

'Or say, Cattivo Soggetto Mio,' returned Gowan, touching the painted face with his brush in the part where the real face had moved, 'a murderer after the fact. Show that white hand of yours, Blandois. Put it outside the cloak. Keep it still.'

Blandois' hand was unsteady; but he laughed, and that would naturally shake it.

'He was formerly in some scuffle with another murderer, or with a victim, you observe,' said Gowan, putting in the markings of the hand with a quick, impatient, unskilful touch, 'and these are the tokens of it. Outside the cloak, man!—Corpo di San Marco, what are you thinking of?'

Blandois of Paris shook with a laugh again, so that his hand shook more; now he raised it to twist his moustache, which had a damp appearance; and now he stood in the required position, with a little new swagger."

I suppose he may be afraid that someday someone will realize who he really is. At this point Henry is very, very lucky I wasn't in the room. When his very sensible dog begins to growl at Blandois Henry tells Blandois to leave the room. However, once Blandois is out of the room and the dog is calm Henry proceeds to "fell him with a blow to the head, and kick him severely with the heel of his boot, so that his mouth was presently bloody". As I read this there is a black cocker spaniel curled up on my lap and Henry Gowan's life is in danger.

I'm skipping the rest of the dog torture to say that shortly after this the ladies take their departure. Fanny points out Mr. Sparkler, who is following them in another gondola. Amy wonders why he hasn’t called yet and Fanny thinks he is working up the courage and she wouldn't be surprised to see him that day. They do find Sparkler at the door and while trying to greet the ladies standing up in his gondola, falls down. Fanny inquires after him, pretending she doesn’t know him. He reminds her they met in Martigny, and says he has come to call on Edward and their father. Mr. Dorrit invites Sparkler to dinner and to the opera later. Mr. Dorrit says he wishes to hire Mr. Gowan and to do portraits of the family. This is how their evening at the opera ends:

Little Dorrit was in front with her brother and Mrs General (Mr Dorrit had remained at home), but on the brink of the quay they all came together. She started again to find Blandois close to her, handing Fanny into the boat.

'Gowan has had a loss,' he said, 'since he was made happy to-day by a visit from fair ladies.'

'A loss?' repeated Fanny, relinquished by the bereaved Sparkler, and taking her seat.

'A loss,' said Blandois. 'His dog Lion.'

Little Dorrit's hand was in his, as he spoke.

'He is dead,' said Blandois.

'Dead?' echoed Little Dorrit. 'That noble dog?'

'Faith, dear ladies!' said Blandois, smiling and shrugging his shoulders, 'somebody has poisoned that noble dog. He is as dead as the Doges!'

The last chapter of this installment is Chapter 7 titled "Mostly, Prunes and Prism" and we begin with Mrs. General trying to make Little Dorrit's lips look pretty among other things I suppose but not making much progress. Try as she might however, and we're told she tries harder than ever to be shaped by Mrs. General Amy doesn't make much progress. Her one comfort during all this is that Fanny is finally being nice to her. Fanny tells Amy one night that she thinks their father is too polite to Mrs. General. She believes Mrs. General has designs on their father and hopes to ensnare him, and their father admires her so much, thinking of her as a wonder, and an acquisition to the family, that he admires her enough to become infatuated, . Fanny says she couldn’t bear such a union and would even marry Sparkler to escape it. Amy is alarmed and can’t believe her sister is serious, but Fanny says she is—especially if she could treat Mrs. Merdle in her own style. Fanny is very cruel to Mr. Sparkler who is very devoted to her:

The last chapter of this installment is Chapter 7 titled "Mostly, Prunes and Prism" and we begin with Mrs. General trying to make Little Dorrit's lips look pretty among other things I suppose but not making much progress. Try as she might however, and we're told she tries harder than ever to be shaped by Mrs. General Amy doesn't make much progress. Her one comfort during all this is that Fanny is finally being nice to her. Fanny tells Amy one night that she thinks their father is too polite to Mrs. General. She believes Mrs. General has designs on their father and hopes to ensnare him, and their father admires her so much, thinking of her as a wonder, and an acquisition to the family, that he admires her enough to become infatuated, . Fanny says she couldn’t bear such a union and would even marry Sparkler to escape it. Amy is alarmed and can’t believe her sister is serious, but Fanny says she is—especially if she could treat Mrs. Merdle in her own style. Fanny is very cruel to Mr. Sparkler who is very devoted to her:"Sometimes she would prefer him to such distinction of notice, that he would chuckle aloud with joy; next day, or next hour, she would overlook him so completely, and drop him into such an abyss of obscurity, that he would groan under a weak pretence of coughing."

What he sees in her I don't know, perhaps she is beautiful but I would think that wouldn't make up for her personality. However, devoted he is and Edward finds Sparkler as his constant companion rather tiresome and often has to sneak away. Sparkler often follows Fanny’s gondola:

"though he was so constantly being paddled up and down before the principal windows, that he might have been supposed to have made a wager for a large stake to be paddled a thousand miles in a thousand hours; though whenever the gondola of his mistress left the gate, the gondola of Mr Sparkler shot out from some watery ambush and gave chase, as if she were a fair smuggler and he a custom-house officer."

Blandois calls upon Mr. Dorrit, who requests him to tell Mr. Gowan that he wants him to do his portrait. On hearing this Henry becomes angry "for he resented patronage almost as much as he resented the want of it", thinking it over though, he changes his mind and goes to see Mr. Dorrit saying he has to take jobs where he can get them. Henry admits to Mr. Dorrit that he is new to the trade and a bad painter saying he had not been brought up to it and it was too late to learn, however, he is no worse than most. Mr. Dorrit still wants him to do it, and Henry suggests they do the portrait in Rome, where they all will be leaving for shortly.

Little Dorrit and Mrs. Gowan become friends and both women have an aversion to Blandois. When Mrs. Gowan bids goodbye to Amy before she leaves Venice, Blandois is there but Mrs. Gowan does manage to tell Amy that she is sure he killed the dog.

Now their time in Venice is over and they leave for Rome where Little Dorrit thinks Mrs. General gets the upper hand for when walking about St. Peter's and the Vatican nobody said what anything was, but everybody said what the Mrs General, Mr Eustace, or somebody else said it was. Now because of that line I had to go look up who Mr. Eustace was:

"John Chetwode Eustace was an Anglo-Irish Catholic priest and antiquary. In 1802 he travelled through Italy with three pupils. During these travels he wrote a journal which subsequently became celebrated in his "A Classical Tour Through Italy". In 1813 the publication of his "Classical Tour" obtained for him sudden celebrity, and he became a prominent figure in literary society. In 1815 he travelled again to Italy to collect fresh materials, but he was seized with malaria at Naples and died there."

Now that they've arrived in Rome Mrs. Merdle pays them a visit and talks about how pleased she is to resume an aquaintance that began at Martigny. Mr. Dorrit asks whether Mr. Merdle will be coming to Rome but Mrs. Merdle says her husband never travels now. This is how the chapter ends:

"Little Dorrit, still habitually thoughtful and solitary though no longer alone, at first supposed this to be mere Prunes and Prism. But as her father when they had been to a brilliant reception at Mrs Merdle's, harped at their own family breakfast-table on his wish to know Mr Merdle, with the contingent view of benefiting by the advice of that wonderful man in the disposal of his fortune, she began to think it had a real meaning, and to entertain a curiosity on her own part to see the shining light of the time."

Kim wrote: "Dear Pickwickians,

Kim wrote: "Dear Pickwickians,We begin this week's installment with Chapter 5 of Book II, titled "Something Wrong Somewhere". We are told that the Dorrits have now been a month or two in Venice and Mr. Dorri..."

The descriptions seem fine to me, and suggest a bit of the Marshalsea. The trip from Mrs. General's to Mr. Dorrit's rooms have a dank, enclosed dungeon feel. Is she being lead up to the royal room? The movement from her rooms to his suggests both the distance that Dorrit has ascended since his change in circumstance and anticipates his new character role. Rather than being the lord of the jail house he is the lord of the family fortune.

If Mr. Dorrit's insensitivity to Amy was seen as unfair when they were residents of the Marshalsea, his attitude now is reprehensible.

Is anyone else ready to reach into the novel and give Mr. Dorrit a good shake? When he is speaking, and trying to be so proper, we are bombarded with the word "I" and the phrase "I - ha" or " "I - hum." I was tempted to count how many "I's" appeared but realized that would be math and that would create math issues ... :-)).

Is anyone else ready to reach into the novel and give Mr. Dorrit a good shake? When he is speaking, and trying to be so proper, we are bombarded with the word "I" and the phrase "I - ha" or " "I - hum." I was tempted to count how many "I's" appeared but realized that would be math and that would create math issues ... :-)).Anyway, Mr. Dorrit's self-centred, self-image is masterfully drawn by a look at his word choice but enough is enough. Could Mr. Dorrit please come down with a case of a sore throat?

Kim wrote: "Chapter 6 is titled "Something Right Somewhere" and so I am looking forward to pleasant things happening in the chapter but it doesn't look good. We start with Henry Gowan "loitering moodily about ..."

Kim wrote: "Chapter 6 is titled "Something Right Somewhere" and so I am looking forward to pleasant things happening in the chapter but it doesn't look good. We start with Henry Gowan "loitering moodily about ..."The portrait of Blandois that Henry Gowan is working on reveals much about both men. Gowan is a failed artist but he is still able to capture the two faces of Blandois in the portrait. Is Blandois a saint or a sinner? We have had earlier references to Blandois as being devil-like and we know he is a criminal. Dickens keeps us wondering what his future role will be, and with each appearance our curiosity and the subsequent tension of not knowing increases.

Like Kim, Gowan's treatment of his companion dog gives us a portal into his inner self. We should feel sorry for Pet as well. In fact, is the fact that Gowan is married to her, and her nickname ""Pet," in anyway suggestive that the way Gowan mistreats his dog foreshadowing the way he will mistreat his wife named "Pet?"

Kim wrote: "The last chapter of this installment is Chapter 7 titled "Mostly, Prunes and Prism" and we begin with Mrs. General trying to make Little Dorrit's lips look pretty among other things I suppose but n..."

Kim wrote: "The last chapter of this installment is Chapter 7 titled "Mostly, Prunes and Prism" and we begin with Mrs. General trying to make Little Dorrit's lips look pretty among other things I suppose but n..."Kim. Thanks for the information on John Eustace.

Fanny's treatment of Mr. Sparkler adds yet another relationship that is anything but equal or happy. The motif of relationships is broad. Some parents have unhealthy relationships with their children like Mr. Dorrit and Amy, and then there are parents who imprison their feelings from their children like Mrs. Clennam to Arthur. Gowan's treatment and feelings towards Pet, and the mystery of Tattycoram are other dysfunctional or as yet unexplained relationships that come to mind as well.

Something tells me we will have to wait some chapters her for our central characters to find themselves into each other's arms.

Peter wrote: "Is anyone else ready to reach into the novel and give Mr. Dorrit a good shake? When he is speaking, and trying to be so proper, we are bombarded with the word "I" and the phrase "I - ha" or " "I - ..."

Peter wrote: "Is anyone else ready to reach into the novel and give Mr. Dorrit a good shake? When he is speaking, and trying to be so proper, we are bombarded with the word "I" and the phrase "I - ha" or " "I - ..."When we started the novel I didn't like Mr. Dorrit, but I equally didn't like Fanny or Tip. By this time however, I so despise Mr. Dorrit - that I feel like I could invite Fanny and Tip to our home for dinner and have a nice time. Although perhaps not both at the same time.

Peter, I like your idea that the pet name "Pet" might foreshadow that Minnie is going to suffer some ill-treatment from her husband sooner or later. I was quite horrified to see how quickly Gowan could fly into a temper, from a seemingly careless and nonchalant attitude towards everything and everybody, and that he would even kick his dog and make him bleed when the animal is already lying at his feet. That surely forebodes evil for his wife.

Peter, I like your idea that the pet name "Pet" might foreshadow that Minnie is going to suffer some ill-treatment from her husband sooner or later. I was quite horrified to see how quickly Gowan could fly into a temper, from a seemingly careless and nonchalant attitude towards everything and everybody, and that he would even kick his dog and make him bleed when the animal is already lying at his feet. That surely forebodes evil for his wife.But then there are people like that, unfortunately.

And then there his Blandois, who is biding his time only to poison the dog. Poisoning is an especially insidious method of murder, and it shows Blandois's character in its true colours. It also makes me think how this motif of poisoning or killing pets has later become a stock element of many psychological thrillers.

Some time ago my husband and I were looking for a new church to attend. There is a small church not too far from where we live - 5 miles I would guess - and someone suggested we go there. The problem was the pastor for that church lives here in our town and whenever we would take our dog for a walk we would pass his house. I always have had cocker spaniels and at the time so did he, only mine are in the house with me usually sitting on my lap, sleeping in my bed, things like that. Cockers have long hair and the hair gets matted - or it will if you don't groom them and ear problems because of the long ears and all kinds of things like that. Unfortunately the pastor kept his cocker spaniel in his yard chained to a dog house as far away from the house as they could put him with no way to get out of the heat without going in the dog house and with his long hair all matted. Every time I walked by I wanted to jump over the fence and take the dog. I just couldn't go to his church just because of how that dog was treated. The dog isn't there anymore so I assume he died.

Some time ago my husband and I were looking for a new church to attend. There is a small church not too far from where we live - 5 miles I would guess - and someone suggested we go there. The problem was the pastor for that church lives here in our town and whenever we would take our dog for a walk we would pass his house. I always have had cocker spaniels and at the time so did he, only mine are in the house with me usually sitting on my lap, sleeping in my bed, things like that. Cockers have long hair and the hair gets matted - or it will if you don't groom them and ear problems because of the long ears and all kinds of things like that. Unfortunately the pastor kept his cocker spaniel in his yard chained to a dog house as far away from the house as they could put him with no way to get out of the heat without going in the dog house and with his long hair all matted. Every time I walked by I wanted to jump over the fence and take the dog. I just couldn't go to his church just because of how that dog was treated. The dog isn't there anymore so I assume he died.

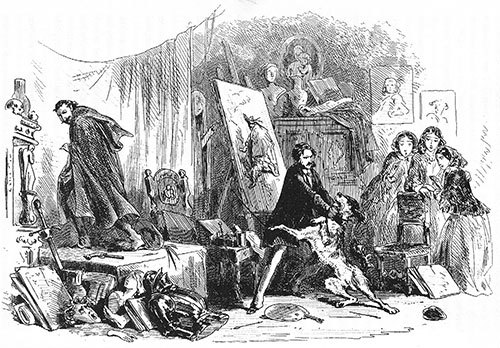

Book II Chapter 6 - Phiz

Book II Chapter 6 - Phiz

Instinct stronger than training

Book II Chapter 6

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"His face was so directed in reference to the spot where Little Dorrit stood by the easel, that throughout he looked at her. Once attracted by his peculiar eyes, she could not remove her own, and they had looked at each other all the time. She trembled now; Gowan, feeling it, and supposing her to be alarmed by the large dog beside him, whose head she caressed in her hand, and who had just uttered a low growl, glanced at her to say, "He won't hurt you, Miss Dorrit."

"I am not afraid of him," she returned in the same breath; "but will you look at him?"

In a moment Gowan had thrown down his brush, and seized the dog with both hands by the collar.

"Blandois! How can you be such a fool as to provoke him! By Heaven, and the other place too, he'll tear you to bits! Lie down! Lion! Do you hear my voice, you rebel!"

The great dog, regardless of being half-choked by his collar, was obdurately pulling with his dead weight against his master, resolved to get across the room. He had been crouching for a spring at the moment when his master caught him.

"Lion! Lion!" He was up on his hind legs, and it was a wrestle between master and dog. "Get back! Down, Lion! Get out of his sight, Blandois! What devil have you conjured into the dog?"

"I have done nothing to him."

"Get out of his sight or I can't hold the wild beast! Get out of the room! By my soul, he'll kill you!"

Commentary

"Although Gowan secretly detests his new-found, foreign friend Monsieur Blandois of Paris, he finds him useful in deliberately upsetting his young wife to keep her in her place. But Gowan's great dog, recognizing Blandois for the villain he is, menaces the sinister Frenchman. In the illustration, Blandois is in the position of Henry Gowan's model, left, while the artist wrestles with the dog, centre; to the right, the three young woman (Little Dorrit, Fanny, and Minnie Gowan) are alarmed by Gowan's brutal treatment of the heretofore gentle animal.

The scene is the romantic and rapidly decaying city of Venice, another instance in the novel of physical decadence. However, whereas Phiz here has illustrated the chapter set in Venice by portraying the studio of Henry Gowan above a bank on an islet, providing little local color but describing well the characters of the artist and the murderer, Blandois, the other illustrators of the novel at this point have been sure to include a gondola to underscore the exotic Italian setting. However, Mahoney's using the text of the closing of the chapter as his subject allows him to complement the original serial illustration by focusing on Blandois' comment that somebody (undoubtedly himself) has poisoned Lion, Gowan's great-hearted dog.

The reader experiences the scene in Phiz's steel-engraving from the perspective of the outsider, Little Dorrit. Upon entering the studio to visit Minnie Gowan, she finds Henry painting a portrait with his model, Blandois, in a hooded cloak in the act of turning away from the viewer. What is not shocking is the dog's growling at the devious Frenchman (which has just occurred), but rather how the fashionably-dressed Henry Gowan savagely rebukes the animal in the presence of the three young ladies — exhibiting his power over the brute by knocking the animal to the floor and (in the accompanying text) repeatedly kicking it until its jaws are bloody. Despite the civilized environment of the dilettante's studio, with its classical statues, bric-a-brac, armor, and sketches, the true subject is the savage nature of a supposedly modern, sophisticated young Englishman of the upper-middle class. Significantly, Phiz embeds emblems of violence around Blandois — a mediaeval broadsword beside him and a flintlock pistol on the platform at his feet. A gorgon's head and fragmentary female bust look up, apparently regarding Blandois rather than Gowan in alarm. Rather than kicking his faithful pet as in the text, Gowan in the illustration appears to be strangling the dog, just as he has been systematically suffocating Minnie (extreme right) emotionally."

Book II Chapter 6 - Phiz

Book II Chapter 6 - Phiz

Mr. Sparkler Under a Reverse of Circumstances

Book II

Chapter 6

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"In effect, the swain was standing up in his gondola, card-case in hand, affecting to put the question to a servant. This conjunction of circumstances led to his immediately afterwards presenting himself before the young ladies in a posture, which in ancient times would not have been considered one of favourable augury for his suit; since the gondoliers of the young ladies, having been put to some inconvenience by the chase, so neatly brought their own boat in the gentlest collision with the bark of Mr. Sparkler, as to tip that gentleman over like a larger species of ninepin, and cause him to exhibit the soles of his shoes to the object of his dearest wishes: while the nobler portions of his anatomy struggled at the bottom of his boat in the arms of one of his men.

However, as Miss Fanny called out with much concern, Was the gentleman hurt, Mr Sparkler rose more restored than might have been expected, and stammered for himself with blushes, "Not at all so." Miss Fanny had no recollection of having ever seen him before, and was passing on, with a distant inclination of her head, when he announced himself by name. Even then she was in a difficulty from being unable to call it to mind, until he explained that he had had the honour of seeing her at Martigny. Then she remembered him, and hoped his lady-mother was well.

"Thank you," stammered Mr. Sparkler, "she's uncommonly well — at least, poorly."

Commentary:

"After the melodramatic violence of Gowan's attack upon his own dog to preserve his model, Blandois, Dickens interjects a farcical scene in which Edmund Sparkler, Mrs. Merdle's son, in trying to give Fanny Dorrit his calling card, loses his balance and falls into the bottom of his gondola — a classic example of "streaky bacon" construction which alternates serious and comic scenes. Continuity between the previous, dramatic illustration and this comic interlude is afforded by the figures of Amy (left) and Fanny (center).

As in the companion illustration, Instinct stronger than Training in the same installment, the scene is the romantic and rapidly decaying city of Venice. However, whereas Phiz here had illustrated the chapter set in Venice by portraying the studio of Henry Gowan above a bank on an islet, he now provides both physical comedy and local color, putting young Sparkler in a characteristically awkward position while revealing Amy's genuine concern for his safety. Phiz has turned Fanny's face towards Edmund Sparkler, so that readers must supply Fanny's expression in witnessing the young man's discomfiture for themselves. Undoubtedly, Fanny is barely controlling a smile as she watches Sparkler's struggling to regain his composure, for this accident is certainly gratifying to a young woman who had been snubbed so recently by his mother."

Book II Chapter 6 - Sol Eytinge Jr.

Book II Chapter 6 - Sol Eytinge Jr.

Mr. and Mrs. Henry Gowan

Book II Chapter 6

Sol Eytinge Jr.

Diamond Edition of Dicken's Little Dorrit 1871

Commentary:

"The eighth paired character study to complement Dickens's narrative, Eytinge's "Mr. and Mrs. Henry Gowan," by virtue of its composition implies that the relationship between the former "Pet" Meagles and the artist Henry Gowan is imbalanced in that Gowan and his gigantic oil canvas on its easel fill the scene, whereas Minnie Gowan is jammed into the upper-left register. In a domestic scene laden with antique statuary, neoclassical cornices, and an elaborate fire-place mantel, the living female form, Minnie, seems a mere afterthought. The subject upon which the couple have focussed their attention and which occupies the centre of the illustration is the large canvas upon which Henry Gowan is still working and which, despite its foreign subject (Blandois in a cape at the Great Saint Bernard in Switzerland), is an extension of Gowan himself, who thus dominates the scene to the near exclusion of his young wife, who curiously regards the painting. Some two months into their European honeymoon, the relationship appears to be deteriorating.

Eytinge captures well the essence of Henry Gowan: the proud, "idle carelessness" and air of "degeneracy, "of being disappointed"; for example, as befits Eytinge's illustration, Henry Gowan constantly conveys the conviction that he has married beneath his class — despite the fact that Minnie's father, a banker, has paid his debts — and "against the wishes of his exalted relations" , the Barnacles. Although this is a honeymoon scene set in Venice, the husband ignores his wife entirely as he studies the effect of his painting in Chapter 6, "Something Right Somewhere," of Book Two, "Riches." This would seem to be the relevant passage, shortly after the arrival of Fanny and Amy Dorrit, claiming mutual acquaintance with the Gowans through the Merdles, at the Gowans' home, although there is no precise correspondence between any passage in the chapter and the illustration:

"Don't be alarmed," said Gowan, coming from his easel behind the door. "It's only Blandois. He is doing duty as a model to-day. I am making a study of him. It saves me money to turn him to some use. We poor painters have none to spare."

Unable to realise visually his subject's false self-deprecation, Eytinge has nonetheless communicated well the essentials of Henry Gowan's nature. In order to adhere to his self-imposed two-character stricture, Eytinge has excluded other significant characters, including Amy and Fanny Dorrit, Gowan's dog Lion, and the elegantly attired Blandois (i. e., Rigaud), from the composition. Even though the illustrator has chosen a less sensational scene, it is one which nevertheless reveals the suave surface by focussing on his indolence rather than on the underlying meanness and brutality that he momentarily reveals in his attack on the dog, the shocking moment that concludes the episode. In balance, one may applaud Eytinge's choice of scene to realise in terms of his detailing, for so many of the scene's contributing elements — from the classical column (right) to the cigar dangling from Henry Gowan's lips — are completely atextual. Minnie looks timidly at her husband's creation, her face a blank of understanding and appreciation: the painting, like the painter himself, is, implies Eytinge, utterly beyond her limited comprehension."

Book II Chapter 7, Sol Eytinge Jr.

Book II Chapter 7, Sol Eytinge Jr.

Prunes and Prism

Book II Chapter 7

Sol Eytinge Jr.

The Diamond Edition of Dicken's Little Dorritt 1871

Commentary:

"The eleventh illustration, although entitled "Prunes and Prism," has as its subject the overbearing, class-conscious companion that Mr. Dorrit has engaged for his daughters on their Grand Tour, the unflappable Mrs. General. Although it would seem to complement the seventh chapter of Book Two, "Mostly Prunes and Prism," the title may be taken as an allusion to the following passage in an earlier chapter, in which she instructs Little Dorrit in elocution:

"I hope so," returned her father. "I — ha — I most devoutly hope so, Amy. I sent for you, in order that I might say — hum — impressively say, in the presence of Mrs. General, to whom we are all so much indebted for obligingly being present among us, on — ha — on this or any other occasion," Mrs General shut her eyes, "that I — ha hum — am not pleased with you. You make Mrs. General's a thankless task. You — ha — embarrass me very much. You have always (as I have informed Mrs. General) been my favourite child; I have always made you a — hum — a friend and companion; in return, I beg — I — ha — I do beg, that you accommodate yourself better to — hum — circumstances, and dutifully do what becomes your — your station."

Mr. Dorrit was even a little more fragmentary than usual, being excited on the subject and anxious to make himself particularly emphatic.

"I do beg," he repeated, "that this may be attended to, and that you will seriously take pains and try to conduct yourself in a manner both becoming your position as — ha — Miss Amy Dorrit, and satisfactory to myself and Mrs General."

That lady shut her eyes again, on being again referred to; then, slowly opening them and rising, added these words: —

"If Miss Amy Dorrit will direct her own attention to, and will accept of my poor assistance in, the formation of a surface, Mr. Dorrit will have no further cause of anxiety. May I take this opportunity of remarking, as an instance in point, that it is scarcely delicate to look at vagrants with the attention which I have seen bestowed upon them by a very dear young friend of mine? They should not be looked at. Nothing disagreeable should ever be looked at. Apart from such a habit standing in the way of that graceful equanimity of surface which is so expressive of good breeding, it hardly seems compatible with refinement of mind. A truly refined mind will seem to be ignorant of the existence of anything that is not perfectly proper, placid, and pleasant." Having delivered this exalted sentiment, Mrs. General made a sweeping obeisance, and retired with an expression of mouth indicative of Prunes and Prism. Book 2, Chapter 5, "Something Wrong Somewhere,"

However, the imperious chaperon appears again in full sail, as it were, at the opening of Chapter 7, "Mostly Prunes and Prism," enforcing the proprieties, or, rather, imposing them on the Dorrit family from the mental vantage point of a coach box. Amy for her part attempts to accede to Mrs. General's attempts at "varnishing" of her surface as the socially correct one, hiding under layers of lacquer the real, the sensitive Little Dorrit, Child of the Marshalsea:

The wholesale amount of Prunes and Prism which Mrs. General infused into the family life, combined with the perpetual plunges made by Fanny into society, left but a very small residue of any natural deposit at the bottom of the mixture. This rendered confidences with Fanny doubly precious to Little Dorrit, and heightened the relief they afforded her.

"Amy," said Fanny to her one night when they were alone, after a day so tiring that Little Dorrit was quite worn out, though Fanny would have taken another dip into society with the greatest pleasure in life, "I am going to put something into your little head. You won't guess what it is, I suspect."

"I don't think that's likely, dear," said Little Dorrit.

"Come, I'll give you a clew, child," said Fanny. "Mrs. General."

Prunes and Prism, in a thousand combinations, having been wearily in the ascendant all day — everything having been surface and varnish and show without substance — Little Dorrit looked as if she had hoped that Mrs. General was safely tucked up in bed for some hours.

Fanny is perceptive enough to see what her sister Amy, pure of heart, is blind to, namely that, as Fanny tells her, "Mrs. General has designs on pa!"

In the 1999 BBC One adaptation of the novel, British actress Pam Ferris provided a performance informed by a perceptive reading the self-deceiving Dickens character who is so determined to enforce a rigid, upper-middle-class code of respectability and impose it upon the Dorrits:

Mrs General is a triumph of genteel respectability. A widow, she has set herself up as a 'companion to ladies'. She hates to be thought of as a working woman and when Mr. Dorrit employs her to 'finish' his daughters, she adopts the pretence that she is a friend of the family, rather than a governess. She is extremely strict about decorum, putting Amy and Fanny through a gruelling training regime. The passage upon which Eytinge based his visual character study actually occurs in Book Two, Chapter 2 ("Mrs. General") which explains how Mr. Dorrit came to employ the widow as a companion on the European tour for his daughters:

In person, Mrs. General, including her skirts which had much to do with it, was of a dignified and imposing appearance; ample, rustling, gravely voluminous; always upright behind the proprieties. She might have been taken; had been taken — to the top of the Alps and the bottom of Herculaneum, without disarranging a fold in her dress, or displacing a pin. If her countenance and hair had rather a floury appearance, as though from living in some transcendently genteel Mill, it was rather because she was a chalky creation altogether, than because she mended her complexion with violet powder, or had turned grey. If her eyes had no expression, it was probably because they had nothing to express. If she had few wrinkles, it was because her mind had never traced its name or any other inscription on her face. A cool, waxy, blown-out woman, who had never lighted well.

Mrs. General had no opinions. Her way of forming a mind was to prevent it from forming opinions. She had a little circular set of mental grooves or rails on which she started little trains of other people's opinions, which never overtook one another, and never got anywhere. Even her propriety could not dispute that there was impropriety in the world; but Mrs. General's way of getting rid of it was to put it out of sight, and make believe that there was no such thing. This was another of her ways of forming a mind — to cram all articles of difficulty into cupboards, lock them up, and say they had no existence. It was the easiest way, and, beyond all comparison, the properest.

Thus, Dickens makes Mrs. General the exemplar of a social attitude (propriety) and in subsequent chapters gives her a distinct voice or verbal presence, but little in the way of physical features for the inspiration of an illustrator. Eytinge, of course, could reference Phiz's original images of Mrs. General for the Chapman and Hall serialisation (in which the earlier illustrator has crammed the widow of the commissariat officer's widow into the lower right corner of "The Travellers," one of two illustrations for the eleventh monthly part, October 1856, but has not developed her), but otherwise he had to select a carriage and fashion appropriate to the above description. Eytinge departs from Phiz's depiction in that this 1871 "Mrs. General" has no massive bonnet and is not shown in full mourning. With her nose held high and lace at her wrists and throat, complemented by a lace handkerchief, Eytinge's figure is far more impressive than Phiz's, and certainly as "dignified and imposing" as Dickens would have his reader think her, although her floral "fascinator" headgear must have struck some of Eytinge's readers as a little fey — a suggestion of Italianate fashion, perhaps."

Book II Chapter 6 - Harry Furniss

Book II Chapter 6 - Harry Furniss

"Miss Fanny meets an Acquaintance in Venice"

Book II Chapter 6

Harry Furniss

Dicken's Library Edition 1910

Text Illustrated:

"In effect, the swain was standing up in his gondola, card-case in hand, affecting to put the question to a servant. This conjunction of circumstances led to his immediately afterwards presenting himself before the young ladies in a posture, which in ancient times would not have been considered one of favourable augury for his suit; since the gondoliers of the young ladies, having been put to some inconvenience by the chase, so neatly brought their own boat in the gentlest collision with the bark of Mr. Sparkler, as to tip that gentleman over like a larger species of ninepin, and cause him to exhibit the soles of his shoes to the object of his dearest wishes: while the nobler portions of his anatomy struggled at the bottom of his boat in the arms of one of his men.

However, as Miss Fanny called out with much concern, Was the gentleman hurt, Mr. Sparkler rose more restored than might have been expected, and stammered for himself with blushes, "Not at all so."

Miss Fanny had no recollection of having ever seen him before, and was passing on, with a distant inclination of her head, when he announced himself by name. Even then she was in a difficulty from being unable to call it to mind, until he explained that he had had the honour of seeing her at Martigny. Then she remembered him, and hoped his lady-mother was well.

"Thank you," stammered Mr. Sparkler, "she's uncommonly well — at least, poorly."

"In Venice?" said Miss Fanny.

"In Rome," Mr. Sparkler answered. "I am here by myself, myself. I came to call upon Mr. Edward Dorrit myself. Indeed, upon Mr. Dorrit likewise. In fact, upon the family."

Turning graciously to the attendants, Miss Fanny inquired whether her papa or brother was within? The reply being that they were both within, Mr. Sparkler humbly offered his arm."

Commentary:

"Whereas Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), the original serial illustrator, in Instinct Stronger than Learning (Part 12: November 1856) had illustrated the chapter set in Venice by portraying the studio of Henry Gowan above a bank on an islet, providing little local color but describing well the characters of the artist and the murderer, Blandois, the other illustrators of the novel at this point have been sure to include a gondola to underscore the exotic Italian setting. However, whereas Mahoney's using the text of the closing of the chapter as his subject allows him to complement the original serial illustration by focusing on Blandois' comment that somebody has poisoned Gowan's dog, Harry Furniss dwells upon Fanny's taking subtle revenge on Edward Sparkler for his mother's refusal to recognize days before at the inn in Switzerland. Furniss thoroughly enjoys his exotic material and the lively gondoliers, an interpretation that may even owe something to The Gondoliers a light-hearted 1889 comic opera by Gilbert and Sullivan. It is easy, however, to lose track of Edward Sparkler, Fanny, and Little Dorrit (center) amidst the Renaissance architecture."

Book II Chapter 5 - James Mahoney

Book II Chapter 5 - James Mahoney

"As his hand went up above his head and came down upon the table, it might have been a blacksmith's"

Book II Chapter 5

James Mahoney

Household Edition 1873

Text Illustrated:

"Uncle?" cried Fanny, affrighted and bursting into tears, "why do you attack me in this cruel manner? What have I done?"

"Done?" returned the old man, pointing to her sister's place, "where's your affectionate invaluable friend? Where's your devoted guardian? Where's your more than mother? How dare you set up superiorities against all these characters combined in your sister? For shame, you false girl, for shame!"

"I love Amy," cried Miss Fanny, sobbing and weeping, "as well as I love my life — better than I love my life. I don't deserve to be so treated. I am as grateful to Amy, and as fond of Amy, as it's possible for any human being to be. I wish I was dead. I never was so wickedly wronged. And only because I am anxious for the family credit."

"To the winds with the family credit!" cried the old man, with great scorn and indignation. "Brother, I protest against pride. I protest against ingratitude. I protest against any one of us here who have known what we have known, and have seen what we have seen, setting up any pretension that puts Amy at a moment's disadvantage, or to the cost of a moment's pain. We may know that it's a base pretension by its having that effect. It ought to bring a judgment on us. Brother, I protest against it in the sight of God!"

As his hand went up above his head and came down on the table, it might have been a blacksmith's. After a few moments' silence, it had relaxed into its usual weak condition. He went round to his brother with his ordinary shuffling step, put the hand on his shoulder, and said, in a softened voice, "William, my dear, I felt obliged to say it; forgive me, for I felt obliged to say it!" and then went, in his bowed way, out of the palace hall, just as he might have gone out of the Marshalsea room.

Commentary:

"The title is somewhat longer in the New York (Harper and Brothers) printing: "It ought to bring a judgment on us. Brother, I protest against it in the sight of God!" As his hand went above his head and came down upon the table, it might have been a blacksmith's — Book 2, chap. v. In the original serial illustrations that Phiz provided, this fifth chapter in the second book had no illustration, there being steel-engravings for both Chapters 3 and 6: The Family Dignity is Affronted (Part 11: October 1856) and Instinct Stronger than Training (Part 12: November 1856) respectively, the former illustration involving Fanny Dorrit, her aristocratic-looking father, and the Swiss innkeeper, and the latter the Dorrit sisters, Pet Gowan, Henry Gowan, and Blandois. The present Mahoney illustration realizes the normally timid Frederick Dorrit's indignation at Fanny's supercilious attitude towards her modest, self-sacrificing sister.

Wealth and their new social standing impose certain behavioral constraints upon the Dorrits, including the proper demeanor and attitudes for the young ladies. Consequently, Mr. Dorrit hires a governess of impeccable credentials, Mrs. General, an officer's widow, to inculcate the appropriate upper-middle-class manners, skills, etiquette, and biases in his daughters. Mrs. General's account of Miss Amy to her new employer is not entirely positive as she feels that Amy is not sufficiently assertive — and not sufficiently class-conscious. William Dorrit fears that her demeanor is suggestive of the taint of prison. In the present illustration, the normally retiring, elderly musician Frederick Dorrit stands up for Amy, expressing nothing less than indignation about Tip and Fanny's treatment of their good-hearted, serviceable sister. The other Dorrits think Frederick demented. Thus, Dickens shows the Dorrits are prisoners of their own biases and prejudices, and that, in ignoring questions of degree in favor of human sympathy, Amy is a true Dickensian heroine.

Supporting himself by gripping the chair-back, Frederick rebukes Fanny (right), who breaks down under her uncle's criticism of her recent conduct. William in glasses (left) and Tip with his monocle are astounded, failing to appreciate the truth of Frederick's accusations. Large, ornate oil-paintings in the hotel dining-room imply the opulence of the family's new surroundings, in Italy, as they take breakfast. Amy, of course, cannot be embarrassed by her uncle's spirited defense of her because she has just left the table, accompanied by Mrs. General. Mr. Dorrit (upper left) has just dropped his French newspaper in amazement at his normally shy brother's anguish, suggested by his hair standing up. Miss Fanny is "sobbing and weeping", as in the text, about to protest that she loves and is grateful to Amy: "And only because I am anxious for the family credit" — an interesting phrasing in light of the family's tight finances only recently being relieved.

To quote Fani-Maria Tsigakou,

The travelers of the early nineteenth century included not only learned or leisured aristocrats but also the new wealthy middle classes eager to take their families on a fashionable tour.

Already in the 1850s, however, the true cognoscenti were venturing further abroad, and the growth of railways and the availability of guidebooks made such continental travel far less exclusive than it would have been in the 1830s, when the action of the novel occurs. William Dorrit does not merely wish his daughters and vacuous son to acquire some sophistication and polish from a trip through Switzerland into Italy; he is attempting to re-invent his family as aristocracy, so that later he can introduce himself in London as having come from the Continent, rather than the Marshalsea."

Book II Chapter 6 - James Mahoney

Book II Chapter 6 - James Mahoney

On the brink of the quay, they all came together."

Book II Chapter 6

James Mahoney

Household Edition 1873

Text Illustrated:

"The Merman with his light was ready at the box-door, and other Mermen with other lights were ready at many of the doors. The Dorrit Merman held his lantern low, to show the steps, and Mr. Sparkler put on another heavy set of fetters over his former set, as he watched her radiant feet twinkling down the stairs beside him. Among the loiterers here, was Blandois of Paris. He spoke, and moved forward beside Fanny.

Little Dorrit was in front with her brother and Mrs. General (Mr. Dorrit had remained at home), but on the brink of the quay they all came together. She started again to find Blandois close to her, handing Fanny into the boat.

"Gowan has had a loss," he said, "since he was made happy to-day by a visit from fair ladies."

"A loss?" repeated Fanny, relinquished by the bereaved Sparkler, and taking her seat.

"A loss," said Blandois. "His dog, Lion."

Little Dorrit's hand was in his, as he spoke.

"He is dead," said Blandois.

"Dead?" echoed Little Dorrit. "That noble dog?"

"Faith, dear ladies!" said Blandois, smiling and shrugging his shoulders, "somebody has poisoned that noble dog. He is as dead as the Doges!"

Commentary:

"The Mahoney woodcut in the New York (Harper and Brothers, New York) edition has a longer caption: Little Dorrit was in front, with her brother and Mrs. General (Mr. Dorrit had remained at home). But on the brink of the quay, they all came together. She started again to find Blandois close to her, handing Fanny into the boat. The emphasis in the illustration is divided between the black-clad Blandois and the angelic Amy, all in white. Fanny, Mrs. General, and the monocled Tip (Edward) are to the right.

Whereas Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), the original serial illustrator, in Instinct Stronger than Learning (Part 12: November 1856) had as his first illustration for the chapter set in Venice the dramatic scene in the studio of Henry Gowan above a bank on an islet, providing little local color but describing well the characters of the artist and the murderer, Blandois, the other illustrators of the novel at this point have been sure to include a gondola (the comic pratfalls of Edmund Sparkler in the original Phiz illustration Mr. Sparkler under a Reverse of Circumstances being Furniss's direct source of inspiration) to make the most of the exotic Italian setting. However, Mahoney's using the text of the closing of the chapter as his subject allows him to complement the original serial illustration by focusing on Blandois' comment that somebody (undoubtedly himself) has poisoned Lion, Gowan's great-hearted dog, whereas Furniss elected to focus on physical comedy.

With the judicious use of chiaroscuro, James Mahoney makes us the see the scene on the Venetian quay intensely, throwing Blandois' face and the flagstones into the light from the gondolier's lantern (left), and placing the tether-post and rope prominently in the foreground, while in the background a domed church (possibly San Michele in Isola) establishes the presence of the Renaissance city."

Book II Chapter 7 - James Mahoney

Book II Chapter 7 - James Mahoney

"Good-bye, my love! Good-bye!" The last words were spoken aloud as the vigilant Blandois stopped, turned his head, and looked at them from the bottom of the staircase."

Book II Chapter 7

James Mahoney

Household Edition 1873

Text Illustrated:

". . . Mrs. Gowan whispered:

"He killed the dog."

"Does Mr. Gowan know it?" Little Dorrit whispered.

"No one knows it. Don't look towards me; look towards him. He will turn his face in a moment. No one knows it, but I am sure he did. You are?"

"I — I think so," Little Dorrit answered.

"Henry likes him, and he will not think ill of him; he is so generous and open himself. But you and I feel sure that we think of him as he deserves. He argued with Henry that the dog had been already poisoned when he changed so, and sprang at him. Henry believes it, but we do not. I see he is listening, but can't hear. Good-bye, my love! Good-bye!"

The last words were spoken aloud, as the vigilant Blandois stopped, turned his head, and looked at them from the bottom of the staircase. Assuredly he did look then, though he looked his politest, as if any real philanthropist could have desired no better employment than to lash a great stone to his neck, and drop him into the water flowing beyond the dark arched gateway in which he stood. No such benefactor to mankind being on the spot, he handed Mrs. Gowan to her boat, and stood there until it had shot out of the narrow view; when he handed himself into his own boat and followed."

Commentary:

"Taking his cue from the original Phiz illustration for the previous chapter, Instinct stronger than Training (November 1856: Part Twelve), Mahoney has the sardonic Blandois wait upon Henry Gowan's wife, Pet, and her new English friend, Amy Dorrit, at the base of the stairs in the Gowan flat in Venice. Both young women strongly suspect that the cruel and cunning Frenchman has poisoned Henry's mastiff because the dog threatened to attack him when he was serving as Henry's model in the studio above — but both are at a loss as how to prove that he is the malefactor, let alone how to persuade Henry that Blandois is hardly a friend. In fact, he terrifies both women, but they cannot determine how to eliminate him from Pet's life as long as Gowan cultivates his friendship in order to keep his wife off-balance. What neither young woman realizes is that Gowan secretly detests his new-found, foreign friend.

Although James Mahoney's illustration is successful insofar as it offers a visual characterization of these three characters, showing how their disparate paths have now crossed in Venice, the illustrator offers none of those interesting background details that inform the Italian scenes in the original serial. Although this is the chapter in which Mrs. General's marital "designs" upon William Dorrit become apparent, Mahoney has responded instead to Blandois' poisoning of Gowan's dog, and the putative menace that he represents to Pet, the elegantly dressed young woman with the sausage-roll curls, shawl, and elegant muff, dressed still in bridal white to distinguish her from the more serviceably attired Amy. In his villainous cloak, Blandois smirks at them both, as if he knows precisely what they are talking about — but cannot gather evidence to support their supposition. In the absence of anyone else whom she can trust, Pet has made a recent acquaintance into a confidante. The only ornamental element, the ornate balustrade, serves to connect the ladies to the right and Blandois to the left, and subtly emphasizes their descent to his level, when he hopes to have them in his power."

Kim wrote: "Book II Chapter 6 - Phiz

Kim wrote: "Book II Chapter 6 - PhizInstinct stronger than training

Book II Chapter 6

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"His face was so directed in reference to the spot where Little Dorrit stood by the easel, tha..."

The "rapidly decaying city of Venice" as the commentary says does serve as a frame for both the illustration and the people within it. Gowan's marriage is in decline, Blandois is a toxic presence, Amy Dorrit must suffer from both her sister's flirtatious dalliance with Mr. Sparkler and her father's abrasive and pompous personality.

The commentary points out the details of swords, broken busts and other flotsam and jetsam. In the middle of it all is an innocent and faithful dog being beaten. A rather violent and disturbing illustration.

Kim, thanks for posting it and you were right. How a person treats a pet reveals much about the owner.

You did a great job in hunting down so many images this week. :-))

Thanks, Kim, for all those wonderful illustrations and the comments, which gave me a good impression of how an illustrator can really add dimension to writing already as multi-dimensional as Dickens's. All in all, I like Phiz best, and then Mahoney.

Thanks, Kim, for all those wonderful illustrations and the comments, which gave me a good impression of how an illustrator can really add dimension to writing already as multi-dimensional as Dickens's. All in all, I like Phiz best, and then Mahoney.As to Sol Eytinge, I cannot help thinking that the female figures always look somehow sketchy (esp. in message 14) and also a bit bird-like. That does not really appeal to me.

I can understand your impulse of climbing over the fence and taking the dog off the pastor, and I wonder why anybody would want to have a dog at all if they treat him with so much neglect.

Tristram wrote: "Thanks, Kim, for all those wonderful illustrations and the comments, which gave me a good impression of how an illustrator can really add dimension to writing already as multi-dimensional as Dicken..."

Tristram wrote: "Thanks, Kim, for all those wonderful illustrations and the comments, which gave me a good impression of how an illustrator can really add dimension to writing already as multi-dimensional as Dicken..."You would think that I would be attracted to anything in anyway bird-like in Dickens, but no Eytinge will make an appearance in my opus on Birds in Dickens. :-))

I am appalled at the idea of a pastor neglecting his dog like that, and just do not understand it. My mother's neighbours got a dog as a pet for their daughter. It broke my heart to see that dog in his small partitioned off area of the garden, watching the little girl playing in the garden, just watching, and never being allowed to join in. Yet this would not qualify as "cruelty" as he was well-fed etc.

I am appalled at the idea of a pastor neglecting his dog like that, and just do not understand it. My mother's neighbours got a dog as a pet for their daughter. It broke my heart to see that dog in his small partitioned off area of the garden, watching the little girl playing in the garden, just watching, and never being allowed to join in. Yet this would not qualify as "cruelty" as he was well-fed etc. But why have a dog at all, if it's not going to be a member of the family? They never even seemed to take him out with them on a walk :(

I have said that over and over - why do people get dogs and just put them in pens in the yard? I've never understood it. When I was little my dad did the same thing, we had two springer spaniels and they were almost always up the yard in a pen next to the garage (well, it was a barn). We were allowed to leave them out once in awhile to play with, but not often and my mother would never, ever let them in the house. The older I got the less I understood this. Why do we have these dogs? Now, my dogs ( just one right now) are of course in the house, Willow not only sleeps in our bed but she crawls under the covers when she's ready to go to sleep. I've never understood how she breathes under there. And most people around here know that I'd put them outside before I'd put her there. :-)

I have said that over and over - why do people get dogs and just put them in pens in the yard? I've never understood it. When I was little my dad did the same thing, we had two springer spaniels and they were almost always up the yard in a pen next to the garage (well, it was a barn). We were allowed to leave them out once in awhile to play with, but not often and my mother would never, ever let them in the house. The older I got the less I understood this. Why do we have these dogs? Now, my dogs ( just one right now) are of course in the house, Willow not only sleeps in our bed but she crawls under the covers when she's ready to go to sleep. I've never understood how she breathes under there. And most people around here know that I'd put them outside before I'd put her there. :-)

I hated the parts here about Gowan's dog. Dogs seem to feature quite often in Dickens's novels, don't they? What with Dora's dog Jip and Bill Sykes's dog - at least he gives some of them a nice life though :)

I hated the parts here about Gowan's dog. Dogs seem to feature quite often in Dickens's novels, don't they? What with Dora's dog Jip and Bill Sykes's dog - at least he gives some of them a nice life though :)

Oh dear, I have just noticed your comments about dogs, Kim and Jean! These stories are more distressing to me than many a tragic Dickens anecdote.

Oh dear, I have just noticed your comments about dogs, Kim and Jean! These stories are more distressing to me than many a tragic Dickens anecdote.Steam is coming out of my ears at the thought of the pastor and his shameful neglect of his cocker spaniel. I wish that I could report him to the authorities, (I hope that he would be prosecuted for neglect in the UK and Ireland!), but at least the poor dog has had a blessed escape from the clutches of his owner! Also Jean, your recounting of the story of your mother's neighbour's dog has given me a lump in my throat and a knot in my stomach. Good luck dreaming sweetly tonight, Hilary!

Thanks for telling the stories though. It is a stark reminder of the neglect and harshness

with which certain people treat animals. This is certainly true in the case of pets.

I should have thought that one of the reasons to have a pet is to lavish love on it as a dear

member of the family. Otherwise why bother?!

About dogs, now, when we were in Argentina, we also visited one of my wife's uncles, who has a very large estancia with a lot of cows for the production of milk. They also have at least three dogs, but they are allowed to roam free on the land, i.e. they are confined to the land immediately around the house. These dogs are well treated and not exactly neglected, but they would not be allowed to enter the house, having huts of their own, and when my son started to play with one of the dogs - the other two dogs showed no interest -, my wife's uncle told him not to spoil the dog too much.

About dogs, now, when we were in Argentina, we also visited one of my wife's uncles, who has a very large estancia with a lot of cows for the production of milk. They also have at least three dogs, but they are allowed to roam free on the land, i.e. they are confined to the land immediately around the house. These dogs are well treated and not exactly neglected, but they would not be allowed to enter the house, having huts of their own, and when my son started to play with one of the dogs - the other two dogs showed no interest -, my wife's uncle told him not to spoil the dog too much.I think that people who live in the countryside simply regard dogs as watchdogs (be it to guard the house, be it to keep discipline among the other animals) and cats as mice-catchers. This is, of course, not the same thing as the pastor and his treatment of his dog - it's just a more matter-of-fact relationship between man and dog ;-)

I understand what you mean Tristram, and certainly farm dogs have a very different life. I have always had border collies, and am aware that they may well have a more interesting life if they were working dogs, rounding up sheep etc., and that special relationship such dogs have with their shepherd, rather than just doing tricks or being silly with me :) Some country dogs live in a farm kitchen with the family, sometimes they are treated as separate from the family. But then that is their life, which they seem to thoroughly enjoy, and they have lots of interest and attention in other ways.

I understand what you mean Tristram, and certainly farm dogs have a very different life. I have always had border collies, and am aware that they may well have a more interesting life if they were working dogs, rounding up sheep etc., and that special relationship such dogs have with their shepherd, rather than just doing tricks or being silly with me :) Some country dogs live in a farm kitchen with the family, sometimes they are treated as separate from the family. But then that is their life, which they seem to thoroughly enjoy, and they have lots of interest and attention in other ways. I think those Argentianian dogs may be similar to that, rather than to our pets, living cooped up in semi-detached or terraced houses or flats, and in need of much of our attention to make up for such a compromised existence; one which we force on them just as much as expect working dogs to do our bidding.

Hilary - I do apologise :( I don't pass on stories of cruelty ... yet this kind of haunts me, the incomprehension of those people who probably thought they were being kind.

No problem at all, Jean. Yes, it's obvious that for very many dog owners they set the bar very low. I'm sure that it is only a small minority who intentionally hurt their dogs. I support, especially in the case of neglect, these dog owners may well be neglectful even of themselves. Education is needed and, of course, penalties and animal rescue. It's certainly very distressing!

No problem at all, Jean. Yes, it's obvious that for very many dog owners they set the bar very low. I'm sure that it is only a small minority who intentionally hurt their dogs. I support, especially in the case of neglect, these dog owners may well be neglectful even of themselves. Education is needed and, of course, penalties and animal rescue. It's certainly very distressing!

We begin this week's installment with Chapter 5 of Book II, titled "Something Wrong Somewhere". We are told that the Dorrits have now been a month or two in Venice and Mr. Dorrit has been "much among Counts and Marquises, and had but scant leisure", but even though he has been so very busy he finally sets an hour aside to hold a conference with Mrs. General. Mr. Dorrit sends his valet for Mrs. General and he finds her:

"on a little square of carpet, so extremely diminutive in reference to the size of her stone and marble floor that she looked as if she might have had it spread for the trying on of a ready-made pair of shoes; or as if she had come into possession of the enchanted piece of carpet, bought for forty purses by one of the three princes in the Arabian Nights, and had that moment been transported on it, at a wish, into a palatial saloon with which it had no connection."

Mrs. General agrees to meet with Mr. Dorrit and is led by the valet to "the presence":

"It was quite a walk, by mysterious staircases and corridors, from Mrs General's apartment,—hoodwinked by a narrow side street with a low gloomy bridge in it, and dungeon-like opposite tenements, their walls besmeared with a thousand downward stains and streaks, as if every crazy aperture in them had been weeping tears of rust into the Adriatic for centuries—to Mr Dorrit's apartment: with a whole English house-front of window, a prospect of beautiful church-domes rising into the blue sky sheer out of the water which reflected them, and a hushed murmur of the Grand Canal laving the doorways below, where his gondolas and gondoliers attended his pleasure, drowsily swinging in a little forest of piles."

I quote these above descriptions of the rooms of both Mr. Dorrit and Mrs. General because of late commentary on the illustrations has mentioned that the illustrators were having trouble because his descriptions needed little visual help. I found the descriptions of both these rooms without any need at all for an illustration for me to "see" what he was describing.

"Browne's greatest problem was that by now Dickens usurped his very function. The author had always written unusually pictorial prose. In Little Dorrit his writing became so graphically suggestive yet selective that it needed little visual help."

Mr. Dorrit wants to talk about Amy, he is not pleased with her behavior since they have become wealthly. He makes sure to tell Mrs. General that Amy has always been his favorite child to which Mrs. General replies that there is no accounting for these partialities. She tells him that Amy has no self-reliance or force of character which Fanny does have. However, she isn't entirely pleased with Fanny either which seems to surprise Mr. Dorrit. She tells him that Fanny 'at present forms too many opinions. Perfect breeding forms none, and is never demonstrative.' She goes on to say that she has talked with Amy several times on her demeanour but has done no good and suggests that he talk to her. Mr. Dorrit sends for Amy and asks Mrs. General to stay for the conversation. When Amy arrives her father asks her why she doesn't seem to be at home there and she saids she need more time. She uses the word father when she answers him which gets this response from Mrs. General:

'Papa is a preferable mode of address,' observed Mrs General. 'Father is rather vulgar, my dear. The word Papa, besides, gives a pretty form to the lips. Papa, potatoes, poultry, prunes, and prism are all very good words for the lips: especially prunes and prism. You will find it serviceable, in the formation of a demeanour, if you sometimes say to yourself in company—on entering a room, for instance—Papa, potatoes, poultry, prunes and prism, prunes and prism.'

Putting aside all the potatoes, poultry and such, how they give a pretty form to the lips, I never knew that Papa would be preferable to Father, I would have thought it the other way around. Her father tells her he is disappointed with her and that she is embarrassing him by not behaving in a manner becoming their position. He also becomes angry because she constantly reminds him of their time in the Marshalea even though she never mentions it. He points out that he was head of the Marshalsea, and people respected Amy and gave her a position because of it. He says he suffered there more than anyone. Yet, he has moved on and so have Fanny and Tip. He provides her with a well-bred woman to guide her and yet she sits in the corner and mopes.

At breakfast Amy asks her father if he minds her going on a visit to Mrs. Gowen, Pet and her husband have also arrived in Venice. Fanny and Mrs. General protest because the Gowens are not of their social circle, but when Edward mentions that they are friends with the Merdle's they all become excited at the idea of a link to the Merdle's and allow Amy's visit. When she leaves the room Frederick loses his temper, he accuses Fanny of having no heart in the way she treats Amy. When Fanny says she only anxious for the family credit I like Frederick for his answer:

'To the winds with the family credit!' cried the old man, with great scorn and indignation. 'Brother, I protest against pride. I protest against ingratitude. I protest against any one of us here who have known what we have known, and have seen what we have seen, setting up any pretension that puts Amy at a moment's disadvantage, or to the cost of a moment's pain. We may know that it's a base pretension by its having that effect. It ought to bring a judgment on us. Brother, I protest against it in the sight of God!'

After he leaves the room the three remaining agree not to tell Amy what happened, and that there is something wrong with Frederick, and Fanny spends the rest of the day "by passing the greater part of it in violent fits of embracing her, and in alternately giving her brooches, and wishing herself dead."