The History Book Club discussion

This topic is about

Malcolm X

CIVIL RIGHTS

>

ARCHIVE - MAY 2016 - SPOILER THREAD - Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention by Manning Marable

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

message 51:

by

Rachel

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

May 17, 2016 11:02AM

In chapter six or seven of the book they were discussing Bayard Rustin and Malcolm debates they did and I just found this on Youtube. So I thought everyone would be interested. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eXUmC...

In chapter six or seven of the book they were discussing Bayard Rustin and Malcolm debates they did and I just found this on Youtube. So I thought everyone would be interested. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eXUmC...

reply

|

flag

Bayard Rustin

Bayard Rustin

Bayard Rustin was a civil rights organizer and activist, best known for his work as adviser to Martin Luther King Jr. in the 1950s and '60s.

“I believe in social dislocation and creative trouble.”

—Bayard Rustin

Synopsis

Bayard Rustin was born in West Chester, Pennsylvania, on March 17, 1912. He moved to New York in the 1930s and was involved in pacifist groups and early civil rights protests. Combining non-violent resistance with organizational skills, he was a key adviser to Martin Luther King Jr. in the 1960s. Though he was arrested several times for his own civil disobedience and open homosexuality, he continued to fight for equality. He died in New York City on August 24, 1987.

Early Life and Education

Bayard Rustin was born on March 17, 1912, in West Chester, Pennsylvania. He had been raised to believe that his parents were Julia and Janifer Rustin, when in fact they were his grandparents. He discovered the truth before adolescence, that the woman he thought was his sibling, Florence, was in fact his mother, who'd had Rustin with West Indian immigrant Archie Hopkins.

Rustin attended Wilberforce University in Ohio, and Cheyney State Teachers College (now Cheney University of Pennsylvania) in Pennsylvania, both historically black schools. In 1937 he moved to New York City and studied at City College of New York. He was briefly involved with the Young Communist League in 1930s before he became disillusioned with its activities and resigned.

Political Philosophy and Civil Rights Career

In his personal philosophy, Rustin combined the pacifism of the Quaker religion, the non-violent resistance taught by Mahatma Gandhi, and the socialism espoused by African-American labor leader A. Philip Randolph. During the Second World War he worked for Randolph, fighting against racial discrimination in war-related hiring. After meeting A. J. Muste, a minister and labor organizer, he also participated in several pacifist groups, including the Fellowship of Reconciliation.

Rustin was punished several times for his beliefs. During the war, he was jailed for two years when he refused to register for the draft. When he took part in protests against the segregated public transit system in 1947, he was arrested in North Carolina and sentenced to work on a chain gang for several weeks. In 1953 he was arrested on a morals charge for publicly engaging in homosexual activity and was sent to jail for 60 days; however, he continued to live as an openly gay man.

By the 1950s, Rustin was an expert organizer of human rights protests. In 1958, he played an important role in coordinating a march in Aldermaston, England, in which 10,000 attendees demonstrated against nuclear weapons.

Martin Luther King and the March on Washington

Rustin met the young civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in the 1950s and began working with King as an organizer and strategist in 1955. He taught King about Gandhi's philosophy of non-violent resistance and advised him on the tactics of civil disobedience. He assisted King with the boycott of segregated buses in Montgomery, Alabama in 1956. Most famously, Rustin was a key figure in the organization of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, at which King delivered his legendary "I Have a Dream" speech on August 28, 1963.

In 1965, Rustin and his mentor Randolph co-founded the A. Philip Randolph Institute, a labor organization for African-American trade union members. Rustin continued his work within the civil rights and peace movements, and was much in demand as a public speaker.

Later Career and Publications

Rustin received numerous awards and honorary degrees throughout his career. His writings about civil rights were published in the collection Down the Line in 1971 and in Strategies for Freedom in 1976. He continued to speak about the importance of economic equality within the Civil Rights Movement, as well as the need for social rights for gays and lesbians.

Bayard Rustin died of a ruptured appendix in New York City on August 24, 1987, at the age of 75.

(Source: Bio.com)

More:

by Bayard Rustin (No photo)

by Bayard Rustin (No photo) by

by

John D'Emilio

John D'Emilio

Edith Green

Edith Green

Democrat Edith Starrett Green represented Oregon’s 3rd Congressional District from 1955 through 1974. During her twenty years in the U.S. House of Representatives, she gained a national reputation for her leadership in shaping federal education policy and her advocacy for equal rights for women. She was known for her independence, tenacity, and ability.

As a member of the House Committee on Education and Labor, Green set the stage for widespread federal aid to higher education. In 1958, she helped pass the National Defense Education Act, which provided support for math and science education and assistance to graduate students in those fields. As chair of the subcommittee on higher education, she led the effort to pass the Higher Education Facilities Act of 1963 and the Higher Education Act of 1965. Those measures authorized, for the first time, funding for college and university libraries and classrooms, and provided the first federal financial aid to undergraduate students.

Green also worked with Rep. Patsy Mink (D-Hawaii) and Sen. Birch Bayh (D-Ind) to pass legislation prohibiting discrimination against women in federally supported education programs. Now known as Title IX of the 1972 Education Act, the provision caused a dramatic expansion of athletic programs for women and gave them access to academic programs and faculty positions that had been closed to them.

Edith Louise Starrett was born on January 17, 1910, in Trent, South Dakota. Her family moved to Roseburg and later to Salem, Oregon, where she graduated from high school. She received a teaching certificate from Oregon Normal School (now Western Oregon University) and attended Willamette University from 1927 to 1929. She taught school in Salem (1930-1941) and received a bachelor's degree in education and English from the University of Oregon in 1939. In 1933, she married Arthur N. Green; they had two sons, James and Richard, and divorced in 1963.

After eleven years of teaching, Edith Green became legislative director for the Oregon Congress of Parents and Teachers. She also worked as director of public and legislative relations for the Oregon Education Association.

Green’s political career began in 1952 when she stood as the Democratic candidate for Oregon secretary of state. She was defeated in that race by the incumbent, Republican Earl T. Newbry. In 1954, she ran against Tom McCall for the U.S. House in Oregon’s 3rd Congressional District (generally east Portland and Multnomah County), winning that contest with 52 percent of the vote. After that race, she easily won re-election.

In the House, Green served on the Education and Labor Committee for eighteen years, leaving in her last term for a seat on the Appropriations Committee. In addition to her work on education and women’s rights, she drafted legislation to equalize pay between men and women, which in 1963 resulted in the Equal Pay Act, and she helped pass President Lyndon B. Johnson’s anti-poverty legislation in 1967. She also was a firm supporter of early civil rights legislation.

Green broke with President Johnson and all but a handful of her House colleagues with her early opposition to the build-up of U.S. troops in Vietnam. She was one of only seven House members to vote against President Johnson’s request in 1965 for funding the escalation of military involvement there.

Independent, tenacious, and firm in her convictions, in the last part of her career, Green alienated the liberal wing of her own party and increasingly allied herself with conservatives of both parties as she questioned the cost and effectiveness of various social programs, including some she had helped pass.

Outside of her House activities, Green supported John F. Kennedy in the 1960 presidential election, chairing his campaign in Oregon and seconding his nomination. She declined President Kennedy’s offer of the ambassadorship to Canada, but Kennedy later appointed her to the Presidential Commission on the Status of Women.

When Green retired from the House of Representatives at the end of 1974, she returned to Portland. In retirement, she taught at Warner Pacific College, served on the State Board of Higher Education, and during the 1976 campaign was co-chair of The National Democrats for Gerald Ford, a long-time colleague in the House.

Edith Green died of cancer on April 21, 1987.

(Source: The Oregon Encyclopedia)

More:

by Matthew F Delmont (no photo)

by Matthew F Delmont (no photo) by

by

Alice Kessler-Harris

Alice Kessler-Harris

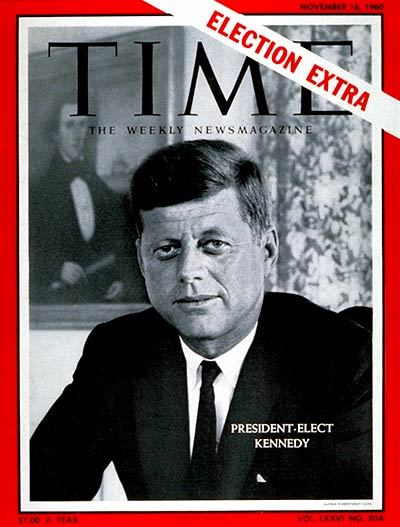

John F. Kennedy

John F. Kennedy

On November 22, 1963, when he was hardly past his first thousand days in office, John Fitzgerald Kennedy was killed by an assassin's bullets as his motorcade wound through Dallas, Texas. Kennedy was the youngest man elected President; he was the youngest to die.

Of Irish descent, he was born in Brookline, Massachusetts, on May 29, 1917. Graduating from Harvard in 1940, he entered the Navy. In 1943, when his PT boat was rammed and sunk by a Japanese destroyer, Kennedy, despite grave injuries, led the survivors through perilous waters to safety.

Back from the war, he became a Democratic Congressman from the Boston area, advancing in 1953 to the Senate. He married Jacqueline Bouvier on September 12, 1953. In 1955, while recuperating from a back operation, he wrote Profiles in Courage, which won the Pulitzer Prize in history.

In 1956 Kennedy almost gained the Democratic nomination for Vice President, and four years later was a first-ballot nominee for President. Millions watched his television debates with the Republican candidate, Richard M. Nixon. Winning by a narrow margin in the popular vote, Kennedy became the first Roman Catholic President.

His Inaugural Address offered the memorable injunction: "Ask not what your country can do for you--ask what you can do for your country." As President, he set out to redeem his campaign pledge to get America moving again. His economic programs launched the country on its longest sustained expansion since World War II; before his death, he laid plans for a massive assault on persisting pockets of privation and poverty.

Responding to ever more urgent demands, he took vigorous action in the cause of equal rights, calling for new civil rights legislation. His vision of America extended to the quality of the national culture and the central role of the arts in a vital society.

He wished America to resume its old mission as the first nation dedicated to the revolution of human rights. With the Alliance for Progress and the Peace Corps, he brought American idealism to the aid of developing nations. But the hard reality of the Communist challenge remained.

Shortly after his inauguration, Kennedy permitted a band of Cuban exiles, already armed and trained, to invade their homeland. The attempt to overthrow the regime of Fidel Castro was a failure. Soon thereafter, the Soviet Union renewed its campaign against West Berlin. Kennedy replied by reinforcing the Berlin garrison and increasing the Nation's military strength, including new efforts in outer space. Confronted by this reaction, Moscow, after the erection of the Berlin Wall, relaxed its pressure in central Europe.

Instead, the Russians now sought to install nuclear missiles in Cuba. When this was discovered by air reconnaissance in October 1962, Kennedy imposed a quarantine on all offensive weapons bound for Cuba. While the world trembled on the brink of nuclear war, the Russians backed down and agreed to take the missiles away. The American response to the Cuban crisis evidently persuaded Moscow of the futility of nuclear blackmail.

Kennedy now contended that both sides had a vital interest in stopping the spread of nuclear weapons and slowing the arms race--a contention which led to the test ban treaty of 1963. The months after the Cuban crisis showed significant progress toward his goal of "a world of law and free choice, banishing the world of war and coercion." His administration thus saw the beginning of new hope for both the equal rights of Americans and the peace of the world.

(Source: The White House)

More:

by

by

Robert Dallek

Robert Dallek by

by

Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.

Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.

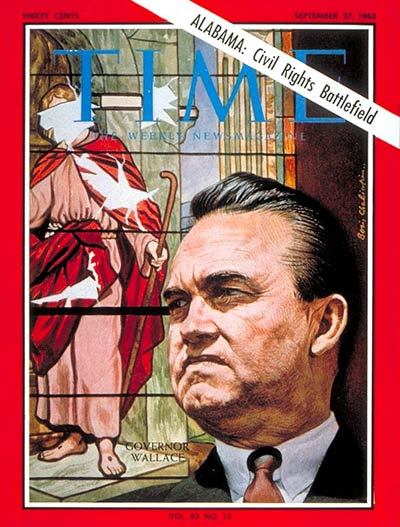

George Wallace

George Wallace

Synopsis

George C. Wallace was born in Clio, Alabama, on August 25, 1919. After law school and military service, he embarked on a career as a judge and local politician. He served four terms as Alabama governor, from the 1960s through the 1980s, and ran unsuccessfully for the U.S. presidency three times. Despite his later efforts to revise his public image, Wallace is remembered for his strong support of racial segregation in the '60s. He died in Montgomery, Alabama, on September 13, 1998.

Background and Early Life

George Corley Wallace Jr. was born on August 25, 1919, in Clio, Alabama. His father, George Corley Sr., was a farmer. His mother, Mozelle Smith Wallace, had been abandoned by her mother and raised in an orphanage in Mobile as a young girl.

Wallace took up boxing as a boy, and won two Golden Gloves state titles while he was a student at Barbour County High School. When he was 15 years old, he served as a legislative page at the Alabama State Capitol in Montgomery. He enrolled at the University of Alabama School of Law in 1937, and graduated with a law degree in 1942.

Military Service and Local Government

After graduating from law school, Wallace entered the U.S. Army Air Corps and served during World War II. He flew multiple bombing missions over Japan in 1945, and was later discharged with a medical disability.

Returning to Alabama, Wallace reunited with his wife, Lurleen (née Burns), whom he'd married in 1943. Deciding to enter local law and politics, Wallace became an assistant to the state attorney general in 1946. The following year, he was elected to the Alabama State Legislature, where he served for two terms.

In 1953, Wallace was elected judge in the Third Judicial Circuit Court of Alabama—a position that he held through 1958. He was given the nickname "The Fighting Little Judge" in reference to his boxing days and his tough approach to his work.

Governor of Alabama

Meanwhile, Wallace was making plans to run for the governorship of his home state. He lost at his first attempt, in 1958. In 1962, when he ran again on a platform of racial segregation and states' rights and was backed by the Ku Klux Klan, he won the election. His inaugural speech concluded with the infamous line, "Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever."

In another event of 1963 that cemented the public perception of the new Alabama governor, Wallace led a "stand-in the schoolhouse door" to prevent two black students, Vivian Malone and James Hood, from enrolling at the University of Alabama, until the National Guard intervened. He continued to oppose integration throughout his term.

In 1964, Wallace briefly entered the primaries for the presidential race, although he lost in the three states in which he appeared on the ballet. He dropped out of contention shortly thereafter, but he used his third-party foothold to run three times in the future.

When the Alabama legislature refused to change the state Constitution to allow him to run for a second term, Wallace put his wife, Lurleen, on the ballot in his place in 1966. After winning a landslide election, she died in office in 1968. Wallace himself was elected again in 1970, and won two more elections in 1974 and 1982—becoming the first individual (and only person to date) to fill four terms as governor of Alabama.

Presidential Campaigns

Wallace also harbored presidential aspirations. In 1968, he ran as an Independent candidate, supported mainly by white, working-class Southerners. In his 1972 campaign, however, he ran as a Democrat. While on the campaign trail in Maryland later that year, Wallace was shot by a would-be assassin named Arthur Bremer. His injuries left him permanently paralyzed below the waist. He managed to still complete the campaign, but ultimately lost the Democratic nomination to George McGovern (who then lost the presidential election to Richard Nixon).

In his third and final presidential attempt, in 1976, Wallace again ran as a Democrat; he was defeated in the primaries by fellow Southerner Jimmy Carter.

Later Life

From the late 1970s onward, Wallace attempted to revise his public image by modifying his previous position on race issues. He claimed that many of his statements had been misunderstood, and he emphasized his populist leanings. In some cases, he issued public apologies for his earlier actions. By the time of his fourth term as Alabama governor, he'd begun receiving a substantial amount of support from black political organizations and black voters. His efforts to improve the state's economy, health care, employment and infrastructure were considered highly successful.

Due to ill health, Wallace retired at the end of his last gubernatorial term, in January 1987. He died of heart failure on September 13, 1998, at the age of 79, in Montgomery, Alabama.

Wallace had married three times. In addition to his marriage to Lurleen Burns, with whom he had four children, he wed Cornelia Ellis Sniveley in 1971 (divorced in 1978) and Lisa Taylor in 1981 (divorced in 1987).

(Source: Bio.com)

More:

by Stephan Lesher (no photo)

by Stephan Lesher (no photo) by

by

Marshall Frady

Marshall Frady

The March on Washington

The March on Washington

On August 28, 1963, more than 200,000 Americans gathered in Washington, D.C., for a political rally known as the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Organized by a number of civil rights and religious groups, the event was designed to shed light on the political and social challenges African Americans continued to face across the country. The march, which became a key moment in the growing struggle for civil rights in the United States, culminated in Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, a spirited call for racial justice and equality.

BACKGROUND

Twice in American history, more than twenty years apart, a March on Washington was planned, each intended to dramatize the right of black Americans to political and economic equality.

The first march was proposed in 1941 by A. Philip Randolph, president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. Blacks had benefited less than other groups from New Deal programs during the Great Depression, and continuing racial discrimination excluded them from defense jobs in the early 1940s. When President Franklin D. Roosevelt showed little inclination to take action on the problem, Randolph called for a March on Washington by fifty thousand people. After repeated efforts to persuade Randolph and his fellow leaders that the march would be inadvisable, Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802 in June 1941, forbidding discrimination by any defense contractors and establishing the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) to investigate charges of racial discrimination. The March on Washington was then canceled. Nearly 2 million blacks were employed in defense work by the end of 1944. Order 8802 represented a limited victory, however; the fepc went out of existence in 1946.

THE MARCH ON WASHINGTON

As blacks faced continuing discrimination in the postwar years, the March on Washington group met annually to reiterate blacks’ demands for economic equality. The civil rights movement of the 1960s transformed the political climate, and in 1963, black leaders began to plan a new March on Washington, designed specifically to advocate passage of the Civil Rights Act then stalled in Congress. Chaired again by A. Philip Randolph and organized by his longtime associate, Bayard Rustin, this new March for Jobs and Freedom was expected to attract 100,000 participants. President John F. Kennedy showed as little enthusiasm for the march as had Roosevelt, but this time the black leaders would not be dissuaded. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference put aside their long-standing rivalry, black and white groups across the country were urged to attend, and elaborate arrangements were made to ensure a harmonious event. The growing disillusion among some civil rights workers was reflected in a speech planned by John Lewis of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, but in order to preserve the atmosphere of goodwill, leaders of the march persuaded Lewis to omit his harshest criticisms of the Kennedy administration.

The march was an unprecedented success. More than 200,000 black and white Americans shared a joyous day of speeches, songs, and prayers led by a celebrated array of clergymen, civil rights leaders, politicians, and entertainers. The Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King’s soaring address climaxed the day; through his eloquence, the phrase “I Have a Dream” became an expression of the highest aspirations of the civil rights movement.

Like its predecessor, the March on Washington of 1963 was followed by years of disillusion and racial strife. Nevertheless, both marches represented an affirmation of hope, of belief in the democratic process, and of faith in the capacity of blacks and whites to work together for racial equality.

(Source: History.com)

More:

by

by

William P. Jones

William P. Jones by

by

J. Patrick Lewis

J. Patrick Lewis

Message to the Grassroots

Message to the GrassrootsVideo

Video/Audio: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a59Kw...

Transcript: http://www.csun.edu/~hcpas003/grassro...

"Message to the Grass Roots" is a public speech delivered by human rights activist Malcolm X. The speech was delivered on November 10, 1963, at the Northern Negro Grass Roots Leadership Conference, which was held at King Solomon Baptist Church in Detroit, Michigan. Malcolm X described the difference between the "Black revolution" and the "Negro revolution", he contrasted the "house Negro" and the "field Negro" during slavery and in the modern age, and he criticized the 1963 March on Washington. "Message to the Grass Roots" was ranked 91st in the top 100 American speeches of the 20th century by 137 leading scholars of American public address.

The speech

A common enemy

Malcolm X began his speech by emphasizing the common experience of all African Americans, regardless of their religious or political beliefs:

What you and I need to do is learn to forget our differences. When we come together, we don't come together as Baptists or Methodists. You don't catch hell because you're a Baptist, and you don't catch hell because you're a Methodist. You don't catch hell 'cause you're a Methodist or Baptist. You don't catch hell because you're a Democrat or a Republican. You don't catch hell because you're a Mason or an Elk, and you sure don't catch hell because you're an American; because if you were an American, you wouldn't catch hell. You catch hell because you're a Black man. You catch hell, all of us catch hell, for the same reason.

Not only did Black Americans share a common experience, Malcolm X continued, they also shared a common enemy: white people. He said that African Americans should come together on the basis that they shared a common enemy.

Malcolm X described the Bandung Conference of 1955, at which representatives of Asian and African nations met to discuss their common enemy: Europeans. He said that just as the members of the Bandung Conference put aside their differences, so Black Americans must put aside their differences and unite.

The Black revolution and the Negro revolution

Next, Malcolm X spoke about the what he called the "Black revolution" and the "Negro revolution". He said that Black people were using the word "revolution" loosely without realizing its full implications. He pointed out that the American, French, Russian, andChinese Revolutions were all carried out by people concerned about the issue of land, and that all four revolutions involved bloodshed. He said that the Black revolutions taking place in Africa also involved land and bloodshed.

By contrast, Malcolm X said, advocates of the Negro revolution in the United States think they can have a nonviolent revolution:

You don't have a peaceful revolution. You don't have a turn-the-other-cheek revolution. There's no such thing as a nonviolent revolution. The only kind of revolution that's nonviolent is the Negro revolution. The only revolution based on loving your enemy is the Negro revolution. ... Revolution is bloody, revolution is hostile, revolution knows no compromise, revolution overturns and destroys everything that gets in its way. And you, sitting around here like a knot on the wall, saying, "I'm going to love these folks no matter how much they hate me." No, you need a revolution. Whoever heard of a revolution where they lock arms, singing "We Shall Overcome"? You don't do that in a revolution. You don't do any singing, you're too busy swinging. It's based on land. A revolutionary wants land so he can set up his own nation, an independent nation. These Negroes aren't asking for any nation—they're trying to crawl back on the plantation.

The house Negro and the field Negro

Malcolm X spoke about two types of enslaved Africans: the "house Negro" and the "field Negro". The house Negro lived in his owner's house, dressed well, and ate well. He loved his owner as much as the owner loved himself, and he identified with his owner. If the owner got sick, the house Negro would ask, "Are we sick?" If somebody suggested to the house Negro that he escape slavery, he would refuse to go, asking where he could possibly have a better life than the one he had.

Malcolm X described the field\ black persons , who he said were the majority of slaves on a plantation. The field Negro lived in a shack, wore raggedy clothes, and ate chittlins. He hated his owner. If the owner's house caught fire, the field Negro prayed for wind. If the owner got sick, the field Negro prayed for him to die. If somebody suggested to the field Negro that he escape, he would leave in an instant.

Malcolm X said that there are still house Negroes and field Negroes. The modern house Negro, he said, was always interested in living or working among white people and bragging about being the only African American in his neighborhood or on his job. Malcolm X said the Black masses were modern field Negroes and described himself as a field Negro.

The March on Washington

Finally, Malcolm X spoke about the March on Washington, which had taken place on August 28, 1963. He said the impetus behind the march was the masses of African Americans, who were angry and threatening to march on the White House and the Capitol. Malcolm X said there were threats to disrupt traffic on the streets of Washington and at its airport. He described it as the Black revolution.

Malcolm X said that President Kennedy called the Big Six civil rights leaders and told them to stop the march, but they told him they couldn't. "Boss, I can't stop it, because I didn't start it." "I'm not even in it, much less the head of it." Malcolm X described how white philanthropist Stephen Currier called a meeting in New York to set up the Council for United Civil Rights Leadership, which provided money and public relations for the Big Six leaders, who took control over the March. As a result, he said, the March on Washington lost its militancy and became "a circus".

They controlled it so tight, they told those Negroes what time to hit town, how to come, where to stop, what signs to carry, what song to sing, what speech they could make, and what speech they couldn't make; and then told them to get out town by sundown. And everyone of those Toms was out of town by sundown.

(Source: Wikipedia)

More:

by Charles River Editors (no photo)

by Charles River Editors (no photo) by

by

Malcolm X

Malcolm X

Malcolm X explaining his "The chickens coming home to roost" statement to the press

Malcolm X explaining his "The chickens coming home to roost" statement to the pressVideo

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SzuOO...

(Source: YouTube)

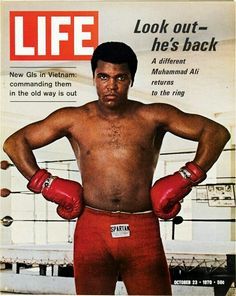

Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali

Synopsis

Born Cassius Clay in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1942, Muhammad Ali became an Olympic gold medalist in 1960 and the world heavyweight boxing champion in 1964. Following his suspension for refusing military service, Ali reclaimed the heavyweight title two more times during the 1970s, winning famed bouts against Joe Frazier and George Foreman along the way. Diagnosed with Parkinson's disease in 1984, Ali has devoted much of his time to philanthropy, earning the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2005.

Early Life

Boxer, philanthropist and social activist Muhammad Ali was born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr. on January 17, 1942, in Louisville, Kentucky. Ali showed at an early age that he wasn't afraid of any bout—inside or outside of the ring. Growing up in the segregated South, he experienced racial prejudice and discrimination firsthand, which likely contributed to his early passion for boxing.

At the age of 12, Ali discovered his talent for boxing through an odd twist of fate. His bike was stolen, and Ali told a police officer, Joe Martin, that he wanted to beat up the thief. "Well, you better learn how to fight before you start challenging people," Martin reportedly told him at the time. In addition to being a police officer, Martin also trained young boxers at a local gym.

Ali started working with Martin to learn how to box, and soon began his boxing career. In his first amateur bout in 1954, he won the fight by split decision. Ali went on to win the 1956 Golden Gloves tournament for novices in the light heavyweight class. Three years later, he won the National Golden Gloves Tournament of Champions, as well as the Amateur Athletic Union's national title for the light heavyweight division.

Olympic Gold

In 1960, Ali won a spot on the U.S. Olympic boxing team, and traveled to Rome, Italy, to compete. At 6' 3", Ali was an imposing figure in the ring, but he also became known for his lightning speed and fancy footwork. After winning his first three bouts, Ali defeated Zbigniew Pietrzkowski from Poland to win the light heavyweight gold medal.

After his Olympic victory, Ali was heralded as an American hero. He soon turned professional with the backing of the Louisville Sponsoring Group, and continued overwhelming all opponents in the ring. Ali took out British heavyweight champion Henry Cooper in 1963, and then knocked out Sonny Liston in 1964 to become the heavyweight champion of the world.

Often referring to himself as "the greatest," Ali was not afraid to sing his own praises. He was known for boasting about his skills before a fight and for his colorful descriptions and phrases. In one of his more famously quoted descriptions, Ali told reporters that he could "float like a butterfly, sting like a bee" in the boxing ring.

Conversion to Islam and Suspension

This bold public persona belied what was happening in Ali's personal life, however. He was doing some spiritual searching and decided to join the black Muslim group, the Nation of Islam, in 1964. At first, he called himself "Cassius X," before settling on the name Muhammad Ali.

A few years later, Ali started a different kind of fight with his outspoken views against the Vietnam War. Drafted into the military in April 1967, he refused to serve on the grounds that he was a practicing Muslim minister, with religious beliefs that prevented him from fighting. He was arrested for committing a felony, and almost immediately stripped of his world title and boxing license.

The U.S. Department of Justice pursued a legal case against Ali, denying his claim for conscientious objector status. He was found guilty of violating Selective Service laws and sentenced to five years in prison in June 1967, but remained free while appealing his conviction. Unable to compete professionally in the meantime, Ali missed more than three prime years of his athletic career. The U.S. Supreme Court eventually overturned the conviction in June 1971.

Boxing Comeback

Prior to the Supreme Court's decision, Ali returned to the ring in 1970 with a win over Jerry Quarry. The following year, Ali took on Joe Frazier in what has been called the "Fight of the Century." Frazier and Ali went toe-to-toe for 14 rounds, before Frazier dropped Ali with a vicious left hook in the 15th. Ali recovered quickly, but the judges awarded the decision to Frazier, handing Ali his first professional loss after 31 wins. Ali soon suffered a second loss, to Ken Norton, but he beat Frazier in a 1974 rematch.

Another legendary Ali fight, against undefeated heavyweight champion George Foreman, took place in 1974. Billed as the "Rumble in the Jungle," the bout was organized by promoter Don King and held in Kinshasa, Zaire. For once, Ali was seen as the underdog to the younger, massive Foreman, but he silenced his critics with a masterful performance. He baited Foreman into throwing wild punches with his "rope-a-dope" technique, before stunning his opponent with an eighth-round knockout to reclaim the heavyweight title.

Ali and Frazier locked horns for their grudge match in Quezon City, Philippines, in 1975. Dubbed the "Thrilla in Manila," the bout nearly went the distance, with both men delivering and absorbing tremendous punishment. However, Frazier's trainer threw in the towel after the 14th round, giving the hard-fought victory to Ali.

After losing his title to Leon Spinks in February 1978, Ali defeated him in the September rematch to become the first boxer to win the heavyweight championship three times. Following a brief retirement, he returned to the ring to face Larry Holmes in 1980, but was overmatched against the younger champion. Following one final loss in 1981, to Trevor Berbick, the boxing great retired from the sport.

Philanthropy and Legacy

In his retirement, Ali has devoted much of his time to philanthropy. He announced that he has Parkinson's disease in 1984, a degenerative neurological condition, and has been involved in raising funds for the Muhammad Ali Parkinson Center in Phoenix, Arizona. Over the years, Ali has also supported the Special Olympics and the Make-A-Wish Foundation, among other organizations.

Muhammad Ali has traveled to numerous countries, including Mexico and Morocco, to help out those in need. In 1998, he was chosen to be a United Nations Messenger of Peace because of his work in developing countries.

In 2005, Ali received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President George W. Bush. He also opened the Muhammad Ali Center in his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky, that same year. "I am an ordinary man who worked hard to develop the talent I was given," he said. "Many fans wanted to build a museum to acknowledge my achievements. I wanted more than a building to house my memorabilia. I wanted a place that would inspire people to be the best that they could be at whatever they chose to do, and to encourage them to be respectful of one another."

Despite the progression of his disease, Ali remained active in public life. He was on hand to celebrate the inauguration of the first African-American president in January 2009, when Barack Obama was sworn into office. Soon after the inauguration, Ali received the President's Award from the NAACP for his public service efforts.

Ali has been married to his fourth wife, Yolanda, since 1986. The couple has one son, Asaad, and Ali has several children from previous relationships, including daughter Laila, who followed in his footsteps by becoming a champion boxer.

Universally regarded as one of the greatest boxers in history, Ali's stature as a legend continues to grow even as his physical state diminishes. He has been celebrated not only for his remarkable athletic skills, but for his willingness to speak his mind, and his courage to challenge the status quo.

(Source: Bio.com)

More:

by

by

Thomas Hauser

Thomas Hauser by

by

Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali

John Ali

John Ali

John Ali, the National Secretary of the Nation of Islam, who is widely believed to have been an undercover FBI agent

In 1958, John Ali was an advisor, friend, and housemate to Malcolm, and in 1963 became the National Secretary of the Black Muslims. When Elijah Muhammads health went south, John Ali took over handling the group's finances and administration. At that time he was also working closely with the FBI and keeping an eye on Malcolm

(Source: AboveTopSecret)

More:

by Michael Friedly (no photo)

by Michael Friedly (no photo) by

by

George Breitman

George Breitman

Socialist Workers Party – SWP

Socialist Workers Party – SWP

The Socialist Workers Party in the U.S. party is historically Trotskyist but these days is better described as Castroist. Their party-affiliated book publisher, Pathfinder Press, publishes a number of titles by Malcolm X, who spoke at some SWP forums after his break from the Nation of Islam. They also publish English translations of many books by Fidel Castro and Che Guevara, as well as their newsletter The Militant.

History

The U.S. Socialist Workers Party is historically rooted in the split in the international communist movement between Stalin and Trotsky, when the Communist Party USA expelled about 100 suspected Trotsky sympathizers who formed a group called the Communist League of America, under the leadership of James P. Cannon. CLA's main activity consisted of publishing The Militant newspaper. The slow growth and isolation of the movement induced its adherents to fuse with the American Workers' Party in 1934 and the Socialist Party in 1935. CLA members were instrumental in organizing the Minneapolis General Strike of 1934 and grew to be a significant faction of the Socialist Party through their militant brand of labor organizing. After its adherents split from the Socialist Party in 1937, the Socialist Workers Party was founded with about 2000 members.

The Stalin-Hitler Pact presented the SWP with its first crisis leading to a party split. A large minority led by Max Schachtman regarded the Soviet Union as no longer being a "workers' state" worthy of defense, while the majority kept the doctrine that it was a "deformed workers' state" to be defended but reformed. The breakaway faction formed the International Socialists. The entry of the US into World War II saw the leadership of the SWP jailed for their opposition to US entry into the war. Ranks were thinned by the military draft and a doctrine towards the war that proved unworkable.

Postwar

The postwar years saw the ranks of the SWP swell to their largest numbers ever on a wave of labor militancy, before the purges of leftists from labor leadership that was soon to follow. The Cochrane faction left the SWP in 1953 over the viability of revolutionary strategy based on a Leninist vanguard party. The Workers World Party followed Sam Marcy out of the SWP in 1959 over the SWP leadership's opposition to Maoism in China and to the Soviet invasion of Hungary, both of which Marcy and his followers supported.

The 1960s saw a renaissance of the SWP through their role in the Fair Play for Cuba Committee, participation in the Civil Rights Movement, and their major role in organizing protests against the US intervention in Vietnam. However, the central role of students in 1960s activism caused cultural and doctrinal drift within the SWP that alienated members who saw labor issues as central to SWP's strategy, causing several factional fights and splits as the decade wore on. To these factions the SWP was growing "opportunist," "petty bourgeois" and "diversionist" over its support for black and Hispanic nationalism (and for a brief while the Black Panther Party), feminism, and gay-rights issues. To the SWP leadership, these Old Left traditionalist factions were "workerist," "ultraleft," and "sectarian." The most significant splits were the ones led by Tim Wohlforth, whose faction founded the Workers League, and James Robertson, whose faction founded the Spartacist League. One follower of the Robertson split was Lyndon LaRouche (Lyn Marcus), who went on his own to teach Free University courses on Marxist theory at Columbia University, form the Labor Committee of the Columbia University student strike in 1968 (later a faction of SDS), and achieve fame as a megalomaniac conspiracy theorist. Wohlforth eventually went on to write a book titled "The Prophet's Children," a retrospective of the Trotskyist experience in which he attempted to digest its lessons, "separating the Marxist kernel from the Leninist husk." An exodus of more labor-oriented members followed the rejection of proposals "For a Proletarian Orientation" at the SWP convention of 1970.

The SWP's attempt to graft New Left identity politics onto Old Left Marxist doctrine did not serve them well. It was seen by black and Hispanic nationalists as a white organization with a program diverging from their primary interest, while racial-essentialist approaches were failing to gain popularity among mainstream minority communities and alienating the American public at large. There was some success recruiting feminist and gay-rights activists, however, radical feminist and radical gay groups, distinguished from mainstream feminist and gay rights activists by ideologies seeing gender as the crux of a social revolution, in turn recruited from the ranks of SWP. The Freedom Socialist Party split was a successful recruitment in 1966 of the Seattle branch to a "socialist feminism" ideology, which saw a nexus of black and feminist politics as the fundamental revolutionary force in the US, by Clara Fraser. By the mid 1970s the ranks of the SWP were waning while radical feminist and radical gay ideologies were nearing their peak and the center of gravity for black and Hispanic issues moved away from the realm of political protest towards the realms of legal advocacy and bureaucracy. David Thorstad, a former member of SWP, went on to found the North American Man-Boy Love Association (NAMBLA).

The SWP made one last attempt to return to its labor roots with a "turn to industry" in 1978, with an imperative for members to find industrial jobs and organize at the workplace. The attendant personal disruption alienated members and the SWP suffered a further decline in membership. That was the SWP's last attempt to implement a strategy of organizing and action. It has since then been mainly concerned with internal functions, publications, and issues of doctrine.

(Source: Rationalwiki)

More:

by Anthony Marcus (no photo)

by Anthony Marcus (no photo) by Jack Ross (no photo)

by Jack Ross (no photo)

Ballot or Bullet Speech

Ballot or Bullet SpeechVideo/Audio

Video/Audio: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7oVW3...

Transcript: http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp...

“The Ballot or the Bullet” was delivered on April 3, 1964, at Cory Methodist Church in Cleveland, Ohio. M

Malcolm X gave his The Ballot or the Bullet speech on April 3, 1964 at a meeting sponsored by the Cleveland, Ohio, chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality. Race dominated Americas domestic agenda at the time. A bill outlawing segregation in public facilities was up for debate in Congress. Millions of Americans had watched television stories showing police dogs attacking African American children protesting for integration in Birmingham, Alabama, had been watched by millions of Americans.

Malcolm X began his speech by urging African Americans to submerge their differences and realize that they all have a common problem -- "political oppression, economic exploitation, and social degradation at the hands of the white man. Noting that 1964 was an election year, Malcolm X told his audience to use the ballot or the bullet. African Americans, now politically mature, are realizing that when white people are evenly divided blacks can be the swing vote to determine who's going to sit in the White House and who's going to be in the dog house. And if they don't cast a ballot, he warned, its going to end up in a situation where were going to have to cast a bullet.

The landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 banning discrimination in public accommodations was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson on July 2, 1964. Hailed by scholars as one of the most influential African Americans in history, Malcolm X was assassinated a year after giving this speech on February 21, 1965.

(Source: NOLO)

More:

by Saladin Ambar (no photo)

by Saladin Ambar (no photo) by

by

Malcolm X

Malcolm X

Ossie Davis

Ossie Davis

Ossie Davis was an American actor, writer and director best known for his screen roles and for his involvement in the Civil Rights Movement.

“Any form of art is a form of power; it has impact, it can affect change. It can not only move us, it makes us move.”

—Ossie Davis

Synopsis

Ossie Davis was born on December 18, 1917, in Cogdell, Georgia. After serving in World War II, Davis embarked on an acting career that would span decades. He starred on Broadway and television and in films. He also wrote and directed. Davis and his wife, actress Ruby Dee, were prominently involved in the Civil Rights Movement. Davis died on February 4, 2005, in Miami, Florida.

Early Life

Raiford Chatman Davis was born in Cogdell, Georgia, on December 18, 1917. The name "Ossie" was bestowed accidentally, when a county clerk misheard his mother's pronunciation of the initials "R.C."

Ossie enrolled at Howard University but dropped out in 1939 to pursue an acting career in New York City. He left New York to serve in World War II, returning in 1946.

Career

Davis modeled his career on the example of Sidney Poitier—an actor who was able to push past the stereotypical roles most frequently offered to African Americans. Like Poitier, Davis sought to bring dignity to the characters he played, including those with menial jobs or from poor backgrounds.

His early jobs on Broadway paved the way for a long career in television and film. While never achieving the commercial success of Poitier, Davis starred in respected films including The Cardinal and Do the Right Thing over the course of five decades. He also worked on television programs such as Evening Shade and The L Word.

In addition to acting, Davis wrote and directed plays and films. Along with Melvin Van Peebles and Gordon Parks, Davis as one of the notable African American directors of his generation, directing films including Cotton Comes to Harlem.

Personal Life

Davis married actress Ruby Dee in 1948. The couple spent most of their married lives in New Rochelle, New York, where they raised a family.

Both Davis and Dee were civil rights activists, maintaining close relationships with Malcolm X, Jesse Jackson and Martin Luther King Jr., among others. Davis delivered a eulogy at the funeral of Malcolm X and participated in a tribute to King at a New York service for the slain leader.

Honors

In 1989, Davis and Dee were inducted into the NAACP Image Awards Hall of Fame. In 1995, they received the National Medal of Arts—the nation's highest honor conferred to an artist on behalf of the country. They were honored by the Kennedy Center in 2004.

Death

Davis was found dead in Miami, Florida, on February 4, 2005. The cause of death was natural and may have been related to Davis's recurring heart problems.

(Source: Bio.com)

More:

by Ossie Davis (no photo)

by Ossie Davis (no photo) by

by

Ruby Dee

Ruby Dee

I just found a six part speech that Farrakhan did talking about Malcolm X on YT. This is the first video of the six. I find myself growing more interested in Farrakhan as we get more into the book. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d_jFZ...

I just found a six part speech that Farrakhan did talking about Malcolm X on YT. This is the first video of the six. I find myself growing more interested in Farrakhan as we get more into the book. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d_jFZ...

Thank you for adding!! I am finding him interesting too and was doing a little research on him the other day. I'm curious how his ideals have changed since his early days with the NOI.

Thank you for adding!! I am finding him interesting too and was doing a little research on him the other day. I'm curious how his ideals have changed since his early days with the NOI.

Dick Gregory

Dick Gregory

Dick Gregory is a comedian and activist who became well known for his biting brand of comedy that attacked racial prejudice.

Synopsis

Activist/comedian Dick Gregory was arrested for civil disobedience several times, and his activism spurred him to run for mayor of Chicago in 1966 and for president in 1968. In the early 1970s Gregory abandoned comedy to focus on his political interests, which widened from race relations to include such issues as violence, world hunger, capital punishment, drug abuse and poor health care.

(Source: Bio.com)

More:

by

by

Dick Gregory

Dick Gregory by

by

Dick Gregory

Dick Gregory

Max Stanford and Revolutionary Action Movement

Max Stanford and Revolutionary Action Movement

The Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM) was the only secular political organization that Malcolm X joined before his fateful trip to Mecca in 1964. Early in 1963, Malcolm took the young Philadelphia militant Max Stanford under his wing. During the last few years of Malcolm's life, few persons were as closely associated with him as was the young Max Stanford. Stanford was a student militant who had influenced both the National Student Youth movement and the Students for a Democratic Society in the early 1960s with a vision of radical black nationalism. Stanford fused the thought of Robert F. Williams on armed self defense with the philosophy of Malcolm X on black self-determination.

To these tenets, Stanford added a sophisticated Marxian revolutionary philosophy, which he derived from a close personal association with the legendary Queen Mother Audley Moore. Malcolm put his blessings on Stanford's Revolutionary Action Movement by becoming an officer of the organization. Among the most important of Stanford's contributions were his assistance to Amiri Baraka and the Newark, New Jersey, movement, his support for members of the Black Liberation Army under Assata Shakur, and his encouragement of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers in Detroit.

He was influential in efforts to encourage Robert F. Williams to assume a nationally prominent leadership role upon Williams return from exile in China. Stanford helped found the African Liberation Support Committee and promoted the concept of "reparations" to descendants of American slavery. And he remained an important voice of criticism of Black Panther strategies of the 1970s. He established the African Peoples Party in the early 1970s in an effort to keep the flame of revolutionary nationalism alive. While underground he embraced Islam and since the early 1970s, he has been known as Muhammad Ahmad. Since the 1970s, he has been one of the leading historians and theoreticians of revolutionary black nationalism.

(Source: Columbia University)

More:

by Akinyele Omowale Umoja (no photo)

by Akinyele Omowale Umoja (no photo) by Peniel E. Joseph (no photo)

by Peniel E. Joseph (no photo)

I came across this interesting article tonight and thought I'd share:

I came across this interesting article tonight and thought I'd share:Centuries-Old Artifacts Discovered Beneath Malcolm X's Childhood Home

By Megan Gannon, Live Science Contributor | May 24, 2016 04:02pm ET

In May 2016, ahead of planned restoration work at the Malcolm X House in Boston, excavators conducted an archaeological investigation.

Credit: City of Boston Archaeology Program

The boyhood home of influential black activist Malcolm X has turned out to be a fascinating archaeological site.

An excavation at the house in Boston's Roxbury neighborhood ended last week. In trenches around the home's foundations, archaeologists unearthed thousands of artifacts, including a vinyl record of American folk songs from the 1950s, as well as toys and housewares from Malcolm's lifetime. They also discovered the remains of a previously unknown 18th-century home.

The house, located at 72 Dale Street, was built in 1874 and has been owned by Malcolm's family since the 1940s. Malcolm lived there with his older half sister Ella Little-Collins after his father died and his mother was institutionalized. Rodnell Collins — Ella's son, who owns the house today — plans to restore the home, possibly to turn it into apartments for graduate students studying civil rights, social justice or African-American history, according to the National Trust for Historic Preservation. But before work could begin on the foundation, archaeologists had to conduct an investigation because of the home's landmark status.

"One of our first surprises was that there was a lot more from Malcolm and Ella's time period than we thought there was going to be," said Joe Bagley, an archaeologist with Boston's City Archaeology Lab who finished digging Friday (May 20). One of the reasons for this, Bagley suspects, is that in the 1970s, the home was vacant and it was vandalized. The windows were broken, and a lot of the home's contents were tossed out and left in the yard. That was bad for the house, but good for archaeology, Bagley said.

"I wish it hadn't happened, but we're recovering a lot of materials that were in the house that the family hadn't seen since the looting in the '70s," Bagley told Live Science, adding that Rodnell Collins has been able to identify toys that he played with and pieces of his mother's mixing bowl. "What I think we're really going to find is, Ella's story more than Malcolm's story here. She was the one who bought most of the materials in the house."

Before Ella bought the house, at least three different families of Irish descent lived at 72 Dale Street, but they left little trace in the archaeological record, Bagley said. Surprisingly, the excavators discovered a foundation for a previously unknown structure and a hoard of artifacts from the 18th century, including clay wig curlers and expensive ceramics that indicate there was a wealthy person's home there more than 200 years ago.

"We're finding thousands of artifacts from at least 100 years before the house was built," Bagley said. "All of our research indicates that there was no previous house on this property at all. So despite what the records say, there's definitely another house here."

Bagley's team also has been using social media to crowdsource, in real time, information about mystery artifacts found on the site. For example, they posted a picture of a broken gold, plastic disc found at the site, and within minutes, someone had identified it as a trading stamp token from a store called Sav-A Coin in South Carolina.

"That would have taken me forever to identify," Bagley said.

(Source: Live Science)

James 67X Warden (Shabazz)

James 67X Warden (Shabazz)

Abdullah Abdur-Razzaq, formerly known as James Monroe King Warden, entered the Nation of Islam at Mosque #7, under Minister Malcolm X.

Abdullah H. Abdur-Razzaq (born James Monroe King Warden December 20, 1931 in Brooklyn, New York; died November 21, 2014 in Manhattan, New York), was an African American activist and Muslim known for his association with Malcolm X.

Early Life

James Monroe King Warden was born in Brooklyn and raised in the impoverished Morningside Park section of Harlem, New York. He attended the The Bronx High School of Science, from which he graduated with honors. He then initially enrolled in the City College of New York but transferred to Lincoln University in Chester County, Pennsylvania after a year, though he soon left that school as well to join the Army. Following his discharge, he returned to Lincoln, graduating with honors in English in 1958.

His Work

He entered the Nation of Islam at Mosque No. 7, on 102 West 116th Street in New York City, under Minister Malcolm X. As was the custom of all others who entered the Nation of Islam, he abandoned the surname of Warden as a vestige of chattel slavery and became the 67th James in Mosque No. 7.

He was eventually promoted to Lieutenant of the Fruit of Islam, subordinate to Captain Joseph X. Gravitt (later known as Yusuf Shah). Subsequently, he was appointed Circulation Manager of the Muhammad Speaks Newspaper for New York, New Jersey and Connecticut, thus directly answerable to Minister Malcolm X.

Subsequent to the schism between Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam, Malcolm formed the Muslim Mosque Incorporated and appointed Mr. Abdur-Razzaq Secretary of the organization, as well as Captain of the Men. Upon Malcolm’s instruction, Abdullah – then still known as James 67X – abandoned the 67X and took the name of James Shabazz.

Brother James, as he was called then, was held responsible for the formation of the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU). The OAAU was a secular organization which Malcolm had also formed – and patterned after Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s Organization of African Unity – through which he planned to charge the United States with the violation of the Human Rights of its chattel slave descendants.

Abdullah H. Abdur-Razzaq, then known as James Shabazz, was a constant and willing aide to Malcolm, both in Malcolm’s capacity as head of the Muslim Mosque, Inc. and as head of the Organization of Afro-American Unity. He remained with, and vigorously assisted Brother Malcolm, prior to – and ever since – his murder on February 21, 1965.

Post Malcolm X Days

Abdur-Razzaq spent the years immediately following Malcolm X's murder under the radar. He would later move to Guyana, where he worked as a farmer. Returning to the U.S. in 1988, he earned his nursing degree, and he worked in this profession up through his retirement in 2004.

In recent years, Abdullah Abdur-Razzaq’s work as Staff Consultant for the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, has been in cataloguing rare photographs, letters and accounts of the great leader’s life and times. Furthermore, his expertise is widely solicited by journalists, authors, film makers and educators alike. In addition to his contributions to a wide array of published works, such as Bruce Perry’s Malcolm X: The Last Speeches, Mr. Abdur-Razzaq has been featured in several television interviews and films, including Make It Plain and Gil Noble’s Like It Is. The DVD version of Jack Baxter’s acclaimed Brother Minister documentary includes an “Exclusive Interview with Abdullah Abdur-Razzaq, Malcolm X’s closest associate.”

Final Years and Death

In April 2013, Abdur-Razzaq returned to his alma mater, Lincoln University to speak about his memories and experiences working with Malcolm X.

Battling leukemia, Abdur-Razzaq was admitted to Harlem Hospital in late 2014. After spending several weeks here, he was transferred to Bellevue Hospital Center in Kips Bay, Manhattan, where he died on November 21, 2014 at the age of 82.

He was survived by a wife, a brother, children, grandchildren, and a large extended family.

(Source: Wikipedia)

More:

by Karl Evanzz (no photo)

by Karl Evanzz (no photo) by Emilie Raymond (no photo)

by Emilie Raymond (no photo)

Benjamin 2X Goodman (Karim)

Benjamin 2X Goodman (Karim)

Benjamin Goodman Karim, former right-hand man to Malcolm X

Benjamin Karim, a Muslim minister and author who was a top assistant to black nationalist icon Malcolm X, died August 2, 2005 after a fall in Richmond, Va. He was 73.

Karim, a native of Suffolk, Va., was working for a recording company in New York City in 1957 when he first heard Malcolm X speak.

The black nationalist spoke so compellingly about the history of slavery that Karim -- whose name was then Benjamin Goodman -- joined the Nation of Islam. He adopted the austere uniform of the Nation of Islam -- a conservative black suit -- and stopped cursing, drinking and eating pork.

Confessing later that he "didn't even know that black people had a history," he heeded Malcolm X's commands to educate himself about African Americans and other cultures. "He had us in a curriculum where we had to study all of the ancient civilizations -- Greeks, Egyptians, Romans. We had to read the London Times and the Peking Times," he recalled in a 1993 interview with the Syracuse Post-Standard.

For the next seven years, Karim served as one of Malcolm X's closest aides. He adopted the name Benjamin 2X and stood in for the Nation of Islam leader at events around the country. He also supervised an education program at the organization's temple in Harlem.

Karim stayed with Malcolm X when he broke from the Nation of Islam in 1964 and founded the Organization for Afro-American Unity. He also introduced Malcolm X at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem on Feb. 21, 1965, a fateful day. Moments into the speech, which was to outline a more mainstream direction for activism, Malcolm X was assassinated by gunmen.

After Malcolm X's death, his assistant rejoined the Nation of Islam and took Karim as his last name. Karim devoted decades to educating the public about the slain icon and his ideas, particularly his calls for self-reliance and education.

Karim was an advisor on Spike Lee's 1992 film "Malcolm X" and wrote "Remembering Malcolm," a book the Washington Post called "a resplendent tribute."

Karim had three sons; two daughters; and 15 grandchildren by his wife, Linda.

(Source: LA Times)

More:

by Louis A. Decaro Jr. (no photo)

by Louis A. Decaro Jr. (no photo) by

by

Manning Marable

Manning Marable

Maya Angelou

Maya Angelou

Synopsis

Born on April 4, 1928, in St. Louis, Missouri, writer and civil rights activist Maya Angelou is known for her 1969 memoir, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, which made literary history as the first nonfiction best-seller by an African-American woman. In 1971, Angelou published the Pulitzer Prize-nominated poetry collection Just Give Me a Cool Drink of Water 'Fore I Die. She later wrote the poem "On the Pulse of Morning"—one of her most famous works—which she recited at President Bill Clinton's inauguration in 1993. Angelou received several honors throughout her career, including two NAACP Image Awards in the outstanding literary work (nonfiction) category, in 2005 and 2009. She died on May 28, 2014.

Early Years

Multi-talented barely seems to cover the depth and breadth of Maya Angelou's accomplishments. She was an author, actress, screenwriter, dancer and poet. Born Marguerite Annie Johnson, Angelou had a difficult childhood. Her parents split up when she was very young, and she and her older brother, Bailey, were sent to live with their father's mother, Anne Henderson, in Stamps, Arkansas.

As an African American, Angelou experienced firsthand racial prejudices and discrimination in Arkansas. She also suffered at the hands of a family associate around the age of 7: During a visit with her mother, Angelou was raped by her mother's boyfriend. Then, as vengeance for the sexual assault, Angelou's uncles killed the boyfriend. So traumatized by the experience, Angelou stopped talking. She returned to Arkansas and spent years as a virtual mute.

During World War II, Angelou moved to San Francisco, California, where she won a scholarship to study dance and acting at the California Labor School. Also during this time, Angelou became the first black female cable car conductor—a job she held only briefly, in San Francisco.

In 1944, a 16-year-old Angelou gave birth to a son, Guy (a short-lived high school relationship had led to the pregnancy), thereafter working a number of jobs to support herself and her child. In 1952, the future literary icon wed Anastasios Angelopulos, a Greek sailor from whom she took her professional name—a blend of her childhood nickname, "Maya," and a shortened version of his surname.

Career Beginnings

In the mid-1950s, Angelou's career as a performer began to take off. She landed a role in a touring production of Porgy and Bess, later appearing in the off-Broadway production Calypso Heat Wave (1957) and releasing her first album, Miss Calypso (1957). A member of the Harlem Writers Guild and a civil rights activist, Angelou organized and starred in the musical revue Cabaret for Freedom as a benefit for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, also serving as the SCLC's northern coordinator.

In 1961, Angelou appeared in an off-Broadway production of Jean Genet's The Blacks with James Earl Jones, Lou Gossett Jr. and Cicely Tyson. While the play earned strong reviews, Angelou moved on to other pursuits, spending much of the 1960s abroad; she first lived in Egypt and then in Ghana, working as an editor and a freelance writer. Angelou also held a position at the University of Ghana for a time.

After returning to the United States, Angelou was urged by friend and fellow writer James Baldwin to write about her life experiences. Her efforts resulted in the enormously successful 1969 memoir about her childhood and young adult years, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, which made literary history as the first nonfiction best-seller by an African-American woman. The poignant work also made Angelou an international star.

Since publishing Caged Bird, Angelou continued to break new ground—not just artistically, but educationally and socially. She wrote the drama Georgia, Georgia in 1972—becoming the first African-American woman to have her screenplay produced—and went on to earn a Tony Award nomination for her role in the play Look Away (1973) and an Emmy Award nomination for her work on the television miniseries Roots (1977), among other honors.

Later Successes

Angelou wrote several autobiographies throughout her career, including All God's Children Need Traveling Shoes (1986) and A Song Flung Up to Heaven (2002), but 1969's I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings continues to be regarded as her most popular autobiographical work. She also published several collections of poetry, including Just Give Me a Cool Drink of Water 'Fore I Die (1971), which was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize.

One of Angelou's most famous works is the poem "On the Pulse of Morning," which she wrote especially for and recited at President Bill Clinton's inaugural ceremony in January 1993—marking the first inaugural recitation since 1961, when Robert Frost delivered his poem "The Gift Outright" at President John F. Kennedy's inauguration. Angelou went on to win a Grammy Award (best spoken word album) for the audio version of the poem.

In 1995, Angelou was lauded for remaining on The New York Times' paperback nonfiction best-seller list for two years—the longest-running record in the chart's history.

Seeking new creative challenges, Angelou made her directorial debut in 1998 with Down in the Delta, starring Alfre Woodard. She also wrote a number of inspirational works, from the essay collection Wouldn't Take Nothing for My Journey Now (1994) to her advice for young women in Letter to My Daughter (2008). Interested in health, Angelou has even published cookbooks, including Hallelujah! The Welcome Table: A Lifetime of Memories With Recipes (2005) and Great Food, All Day Long (2010).

Angelou's career has seen numerous accolades, including the Chicago International Film Festival's 1998 Audience Choice Award and a nod from the Acapulco Black Film Festival in 1999 for Down in the Delta; and two NAACP Image Awards in the outstanding literary work (nonfiction) category, for her 2005 cookbook and 2008's Letter to My Daughter.

Personal Life

Martin Luther King Jr., a close friend of Angelou's, was assassinated on her birthday (April 4) in 1968. Angelou stopped celebrating her birthday for years afterward, and sent flowers to King's widow, Coretta Scott King, for more than 30 years, until Coretta's death in 2006.

Angelou was good friends with TV personality Oprah Winfrey, who organized several birthday celebrations for the award-winning author, including a week-long cruise for her 70th birthday in 1998.

After experiencing health issues for a number of years, Maya Angelou died on May 28, 2014, at her home in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. The news of her passing spread quickly with many people taking to social media to mourn and remember Angelou. Singer Mary J. Blige and politician Cory Booker were among those who tweeted their favorite quotes by her in tribute. President Barack Obama also issued a statement about Angelou, calling her "a brilliant writer, a fierce friend, and a truly phenomenal woman." Angelou "had the ability to remind us that we are all God's children; that we all have something to offer," he wrote.

(Source: Bio.com)

More:

by

by

Peter Jennings

Peter Jennings by

by

Maya Angelou

Maya Angelou

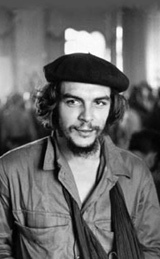

Che Guevara

Che Guevara

Synopsis

Born in Rosario, Argentina, in 1928, Ernesto "Che" Guevara de la Serna studied medicine before traveling around South America, observing conditions that spurred his Marxist beliefs. He aided Fidel Castro in overturning the Batista government in the late 1950s, and then held key political offices during Castro's regime. Guevara later engaged in guerrilla action elsewhere, including in Bolivia, where he was captured and executed in 1967.

Doctor

Che Guevara was born into a middle-class family on June 14, 1928, in Rosario, Argentina. He was plagued by asthma in his youth but still managed to distinguish himself as an athlete. He also absorbed the left-leaning political views of his family and friends, and by his teens had become politically active, joining a group that opposed the government of Juan Perón.

After graduating from high school with honors, Guevara studied medicine at the University of Buenos Aires, but in 1951 he left the school to travel around South America with a friend. The poor living conditions he witnessed on their nine-month journey had a profound effect on Guevara, and he returned to medical school the following year, intent on providing care for the needy. He received his degree in 1953.

Guerrilla

However, as Guevara's interest in Marxism grew, he decided to abandon medicine, believing that only revolution could bring justice to the people of South America. In 1953 he traveled to Guatemala, where he witnessed the CIA-backed overthrow of its leftist government, which only served to deepen his convictions.

By 1955, Guevara was married and living in Mexico, where he met Cuban revolutionary Fidel Castro and his brother Raúl, who were planning the overthrow of Fulgencio Batista's government. When their small armed force landed in Cuba on December 2, 1956, Guevara was with them and among the few that survived the initial assault. Over the next few years, he would serve as a primary adviser to Castro and lead their growing guerrilla forces in attacks against the crumbling Batista regime.

Minister

In January 1959 Fidel Castro took control of Cuba and placed Guevara in charge of La Cabaña prison, where it is estimated that perhaps hundreds of people were executed on Guevara's extrajudicial orders. He was later appointed president of the national bank and minister of industry, and did much to assist in the country's transformation into a communist state.

In the early 1960s, Guevara also acted as an ambassador for Cuba, traveling the world to establish relations with other countries, most notably the Soviet Union, and was a key player during the Bay of Pigs invasion and the Cuban Missile Crisis. He also authored a manual on guerrilla warfare, and in 1964 delivered a speech to the United Nations in which he condemned U.S. foreign policy and the apartheid in South Africa.

Martyr

By 1965, with the Cuban economy in shambles, Guevara left his post to export his revolutionary ideologies to other parts of the world. He traveled first to to the Congo to train troops in guerrilla warfare in support of a revolution there, but left later that year when it failed.

After returning briefly to Cuba, in 1966 Guevara departed for Bolivia with a small force of rebels to incite a revolution there. He was captured by the Bolivian army and killed in La Higuera on October 9, 1967.

Legacy

Since his death, Guevara has become a legendary political figure. His name is often equated with rebellion, revolution and socialism. Others, however, remember that he could be ruthless and ordered prisoners executed without trial in Cuba. In any case, Guevara's life continues to be a subject of great public interest and has been explored and portrayed in numerous books and films, including The Motorcycle Diaries (2004), which starred Gael García Bernal as Guevara, and the two-part biopic Che (2008), in which Benicio Del Toro portrayed the revolutionary.

(Source: Bio.com)

More:

by

by

Jon Lee Anderson

Jon Lee Anderson by

by

Ernesto Che Guevara

Ernesto Che Guevara

Palestinian Liberation Organization

Palestinian Liberation Organization

The Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) was established in May 1964 in Jordan. The Palestine Liberation Organisation was a group that sort to combine various Arab organisations under one banner. The PLO’s primary objective was to gain (though from their point of view regain) the land handed by the United Nations to Israel. The PLO’s impact on recent Middle East history has been marked.

In its infancy, the PLO was not associated with violence. But from 1967 on, it became dominated by an organisation called Fatah – meaning liberation. This was the Syrian wing led by Yasir Arafat. It became more extreme as Israel became more successful militarily (1967 and 1973) and more intransigent about handing back land conquered from the Arabs (Sinai and the Golan Heights in particular). Even more extreme units developed within the PLO. Probably the two most associated with terrorism were ‘Black September’ and the ‘Palestinian Front for the Liberation of Palestine’. These two groups believed that the only way Israel could be forced into returning land was to use violence – and bombing, hijacking and murder became their modus operandi.

The most infamous act of terrorism, among many, was the attack on the Israeli Olympic squad at the Munich Olympics in September1972. Though this attack was carried out by members of ‘Black September’, the main thrust of attention was on the umbrella movement it was in – the PLO. At the Munich Olympics, two Israeli wrestlers were killed outright by the terrorists while nine were held hostage. An attempted rescue bid by the German police failed and the nine athletes were killed along with two German police and five terrorists. The surviving terrorists were arrested and imprisoned. Just six weeks later they were flown to Libya as a German airliner had been hijacked by ‘Black September’ and the threat of killing all on board was enough to win the freedom of those who had been involved in the Munich murders. They returned as heroes. To many in the world, those who had carried out these killings were heartless terrorists. To many in the Arab world they were heroes ready to lay down their lives for the Palestinian people. Such an approach was to develop into Palestinian suicide bombers in Israel in the later years of the Twentieth Century and in the first few years of the Twenty First Century.

King Hussein of Jordan attempted to use his influence in the Arab world to moderate the deeds of the more extreme members of the PLO. This only led to a civil war in Jordan itself in September 1970 which resulted in the guerrilla units of the PLO withdrawing to Syria and the Lebanon. Here they felt as if they had more support from the people living there. Many in Lebanon saw them as freedom fighters who would help reclaim the Golan Heights. In Syria, the government did little to stop their activities.

In October 1974, at a meeting in Rabat of representatives from all Arab states, it was announced that the PLO would assume full responsibility for all Palestinians at a national and international level. On March 22nd 1976, PLO representatives were admitted into the United Nations to debate conditions in the Israeli-occupied west bank of the Jordan. Such a meeting gave the PLO the status it was desperate to achieve but there were those in the PLO who felt that Arafat was heading too much towards a political role and moving away from a role that would force Israel to hand over territory to the Palestinians – i.e. the use of violence as a means of persuasion. In fact, Arafat was prepared at this time to sanction both but hard-liners in the PLO could not accept his ideas. This led to an internal feud within the PLO in 1978 which ended with Arafat the recognised leader of the PLO but with a small but significant group of hard-liners out of his control.

(Source: History Learning Site)

More:

by Helena Cobban (no photo)

by Helena Cobban (no photo) by Paul Thomas Chamberlin (no photo)

by Paul Thomas Chamberlin (no photo)