Doorways in the Sand discussion

Doorways in the Sand

>

Chap 7 to 9: Reversal to Answers of a Sort

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

message 1:

by

carol.

(new)

Apr 04, 2016 05:11PM

Mod

Mod

reply

|

flag

This part is very funny, and I can't help but smile thinking to the genius method found to graduate Fred, beating in this way his genius method to continue to attend. :)

This part is very funny, and I can't help but smile thinking to the genius method found to graduate Fred, beating in this way his genius method to continue to attend. :)

Continuing my reading! Further thoughts.

Continuing my reading! Further thoughts.<> I take back all my nasty thoughts about the first chapter. The impromptu doctorate was quite probably my favorite scene of the book (so far at least), and was laugh-out-loud hilarious. Particularly the line about some of the professors being fellow undergraduates when Fred started and feeling awkward about the whole thing.

<> I found the reversal side-effects *odd*. I would have expected it to manifest itself in going from left to right handed, and maybe some other subtle changes, not this full list of molecular and physiological changes. I'm not doubting them (unlike history or university stuff, I haven't the foggiest notion of chemistry or physics), but they were definitely more bizarre than I expected them to be. Actually, the word that comes to mind time and again here is dreamlike, phantasmagoric. Having everything flipped back-to-front is very much like what you might expect to happen in a dream.

<> The entire conspiracy, as explained by Nadler in the 9th chapter, is ridiculous but makes a certain sort of sense. Although personally, if I were to pick objects that would have this kind of unspeakable importance, I'd have said the Magna Carta (if British), or the Imperial Regalia of Japan. But this is a quibble, and as I am not British, I cannot say just how attached they are to the Crown Jewels. Mind, I got to see them in person a couple of weeks ago, and they were properly impressive.

<> The more I read Zelazny, the more I find myself thinking about the ways in which Zelazny and the other greats of the Golden Age of Sci-Fi (Asimov, Silverberg, Heinlein, etc) differed in style from the more modern authors (Max Gladstone, Brandon Sanderson, Seanan McGuire, etc). It's enough to give me mild culture shock, really, since I've read far more of the latter than the former. In particular, I think modern authors tend to *explain* far more, at all levels. More explanation of the setting, of the technological or magical systems, more description, more character background, etc. On the other hand, Zelazny seems to expect a far more erudite audience, with his references to everything and anything under the sun -- I doubt many a modern author would include references to Henry Moore or Bacchanalia.

Very interesting, Mikhail. I agree, the conspiracy is somewhat ridiculous, but appropriate for a screwball-seeming comedy (nobody dies, at least permanently).

I'm completely sure I didn't understand the inversion at all when I read it as a teen, but when re-reading after a year of organic chemistry, it was a major "ah-ha!" moment. Brilliance. Stereoisocopic brandy and absorption issues. I'm not sure there was a reason for writing/etc to be reversed, but it fits with Alice in Wonderland.

It's interesting that you make that connection about explanations. I agree. I also think they were more practiced authors, and thus got better. Zelazny has a ton of short stories, and I feel he tends to be very economical with his world-building, telling you only what you need to know. In contrast, Brandon Sanderson, Kim Stanley Robinson and Neal Stephenson feel like they are more in love with their ideas, so they spend long pages sidetracked just so they can show how this one idea worked out. For instance, Zelazny never does explain much about the animal disguises, just that the aliens were wearing detachable costumes, and that he had a glimpse of something inside. KSR and NS would have definitely tried to explain that (I'm rather disenchanted with the NS book I'm reading). I like the old-school because of the immersion style.

It makes one wonder--are they trying to be more accessible now? Or have reader expectations shifted?

I'm completely sure I didn't understand the inversion at all when I read it as a teen, but when re-reading after a year of organic chemistry, it was a major "ah-ha!" moment. Brilliance. Stereoisocopic brandy and absorption issues. I'm not sure there was a reason for writing/etc to be reversed, but it fits with Alice in Wonderland.

It's interesting that you make that connection about explanations. I agree. I also think they were more practiced authors, and thus got better. Zelazny has a ton of short stories, and I feel he tends to be very economical with his world-building, telling you only what you need to know. In contrast, Brandon Sanderson, Kim Stanley Robinson and Neal Stephenson feel like they are more in love with their ideas, so they spend long pages sidetracked just so they can show how this one idea worked out. For instance, Zelazny never does explain much about the animal disguises, just that the aliens were wearing detachable costumes, and that he had a glimpse of something inside. KSR and NS would have definitely tried to explain that (I'm rather disenchanted with the NS book I'm reading). I like the old-school because of the immersion style.

It makes one wonder--are they trying to be more accessible now? Or have reader expectations shifted?

Any chance you could translate the chemistry involved into layman's english? I got some basic idea of molecules being reversed and this changes things, but that's about as far as it goes.

Any chance you could translate the chemistry involved into layman's english? I got some basic idea of molecules being reversed and this changes things, but that's about as far as it goes.I'm *personally* more fond of the new style, though I would say that Neal Stephenson isn't actually all that new style. His famous books were written in the early 90s (Snow Crash, Diamond Age), so I'd say he's more halfway between Zelazny in the 70s and Gladstone (first novel published in 2012) or Sanderson (who broke out with Mistborn in 2006).

As for what changed... I think it's a cultural change, a kind of mainstreaming of the genre. I was at a talk between Gladstone, Stross, and Jon Williams in Boston a few months back, and they talked a little about how the authors of the era of Asimov and Zelazny and Tolkien were basically creating new genres from scratch. You have some precursors (Dunsany, say, or Beowulf), but essentially they were bringing in a lot of their own lives as engineers or scholars into the writing, and primarily making it for other engineers or what-not. But then along comes Star Wars, along comes LotR as a mass event, and the new generation of authors basically grew up in the cocoon of Genre Fiction. So for them, Sci-Fi isn't "engineering writ imaginatively" but a specific literature with its own tropes and tools, to be used and abused.

Which makes me thing that the change is that the authors of Zelazny's era, or even more the authors of Heinlein's era, were basically writing utterly New Things, and writing them for an audience that dwelled in a different time. Authors of today, Gladstone et al, are writing for an audience that is *familiar* with basic Sci-Fi, familiar with fantasy, etc. You couldn't get away with writing a basic quest story like LotR anymore -- it's been done, and then copied over a thousand times, and your readers know it all. If you want to succeed, you need to twist things, make them different, and this entails explaining how it's different, what is unique.

Mikhail wrote: "Any chance you could translate the chemistry involved into layman's english? I got some basic idea of molecules being reversed and this changes things, but that's about as far as it goes.

Mikhail wrote: "Any chance you could translate the chemistry involved into layman's english? I got some basic idea of molecules being reversed and this changes things, but that's about as far as it goes.I'm *per..."

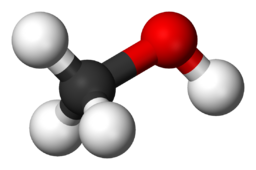

A lot of organic molecules have a "right-handed" and "left-handed" form. It's exactly like a mitten -- the atoms are all hooked up the same way, only in a mirror image. Obviously requires fairly complex molecules.

I was going research it later, because it's a very visual concept, but Mary thought of a nice short way to explain it.

Though chemistry likes to draw molecules in two dimension, actually they have a specific three-dimensional shape.

H

|

H -- C --OH

|

H

is how we draw CH3OH methanol on paper, but actually it is shaped quite differently. If I remember right, it's because mild, mild attractions exist between some molecules, so that methanol looks like this:

Technically, Zelazny is referring to a sub-class of stereoisomers called 'enantiomers' which are mirror images of each other that are non-superimposable. Human hands are an analog of stereoisomerism. "Two compounds that are enantiomers of each other have the same physical properties, except for the direction in which they rotate polarized light and how they interact with different optical isomers of other compounds. As a result, different enantiomers of a compound may have substantially different biological effects. In nature, only one enantiomer of most chiral biological compounds, such as amino acids (except glycine, which is achiral), is present." Thus, Fred would experience nutritional deficiencies because of our amino acids.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stereoi...

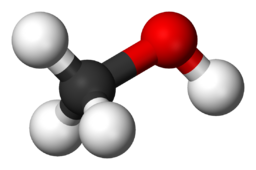

Though chemistry likes to draw molecules in two dimension, actually they have a specific three-dimensional shape.

H

|

H -- C --OH

|

H

is how we draw CH3OH methanol on paper, but actually it is shaped quite differently. If I remember right, it's because mild, mild attractions exist between some molecules, so that methanol looks like this:

Technically, Zelazny is referring to a sub-class of stereoisomers called 'enantiomers' which are mirror images of each other that are non-superimposable. Human hands are an analog of stereoisomerism. "Two compounds that are enantiomers of each other have the same physical properties, except for the direction in which they rotate polarized light and how they interact with different optical isomers of other compounds. As a result, different enantiomers of a compound may have substantially different biological effects. In nature, only one enantiomer of most chiral biological compounds, such as amino acids (except glycine, which is achiral), is present." Thus, Fred would experience nutritional deficiencies because of our amino acids.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stereoi...

Always a good thing. Seriously--who can work concepts like that into a book with talking kangaroos? Genius.

Mikhail wrote: "In particular, I think modern authors tend to *explain* far more, at all levels. More explanation of the setting, of the technological or magical systems, more description, more character background, etc."

Mikhail wrote: "In particular, I think modern authors tend to *explain* far more, at all levels. More explanation of the setting, of the technological or magical systems, more description, more character background, etc."True, but not necessarily better. Since somewhen in the 80s, books started to get more pages - double or triple the previous size. I learned that publishers requested for larger books, so authors delivered. I also think it has to do with easier text production with the advent of personal computers - rearranging textual passages using copy-paste was so much easier.

So, authors had to fill in the pages - with explanation, more depth.

Me, I like shorter books. The concentrated form under 300 pages which leaves room for own thoughts. Which is a completely different style of reading - its more actively consuming!

Nowadays, one can be happy if you can get a standalone novel instead of a series. But standalones are usually more than 600 pages instead of those happy 300 pages in the past.

Novellas, novelettes or short stories are not an adequate solution because they have different scopes.

I find Zelazny's style here very refreshing. It's breezy and conversational which allows a lot of big ideas to be expressed without them weighing so heavily (just like with PKD). Maybe authors today are worried they won't be taken seriously - for sure, the genre is perceived differently today and occupies a different niche in literature. Beyond Gibson, Stephenson, Reynolds, and a few others, though, I'm ignorant when it comes to recent scifi. I'd be curious to learn how others would characterize it.

I find Zelazny's style here very refreshing. It's breezy and conversational which allows a lot of big ideas to be expressed without them weighing so heavily (just like with PKD). Maybe authors today are worried they won't be taken seriously - for sure, the genre is perceived differently today and occupies a different niche in literature. Beyond Gibson, Stephenson, Reynolds, and a few others, though, I'm ignorant when it comes to recent scifi. I'd be curious to learn how others would characterize it.

Andreas wrote: "Since somewhen in the 80s, books started to get more pages - double or triple the previous size. ."

Andreas wrote: "Since somewhen in the 80s, books started to get more pages - double or triple the previous size. ."how true. Getting how-to-write books out of the library, I've read some old ones where they advise that the best length is about 60,000 words. Nowadays, if you want to publish a novel that length, your choices are being a big name already, or indie.

Mary wrote: "how true. Getting how-to-write books out of the library, I've read some old ones..."

Interesting!

It's also rather curious as a cultural trend that we are longer for bigger, longer more. I meet a lot of people that are slower readers and can only read a relatively smaller number of books due to time/availability. I also hear many people refuse to start series that aren't finished. So I would think some people would enjoy more 'efficient' stories that are one-offs, like so many of the old sci-fi authors.

Personally, when Sanderson puts out sequels to Way of Kings (which was 700plus pages), I certainly wouldn't plan on re-reading the last before re-reading the next--too much time commitment. I thought there was a ton of filler in that book.

Interesting!

It's also rather curious as a cultural trend that we are longer for bigger, longer more. I meet a lot of people that are slower readers and can only read a relatively smaller number of books due to time/availability. I also hear many people refuse to start series that aren't finished. So I would think some people would enjoy more 'efficient' stories that are one-offs, like so many of the old sci-fi authors.

Personally, when Sanderson puts out sequels to Way of Kings (which was 700plus pages), I certainly wouldn't plan on re-reading the last before re-reading the next--too much time commitment. I thought there was a ton of filler in that book.

I seem to recall reading (possibly on Charlie Stross's blog), that one of the reasons for books getting bigger is that it allowed publishers to justify putting higher prices on them. The idea that "fatter book = should cost more" is embedded somewhere deep in the lizard brain.

I seem to recall reading (possibly on Charlie Stross's blog), that one of the reasons for books getting bigger is that it allowed publishers to justify putting higher prices on them. The idea that "fatter book = should cost more" is embedded somewhere deep in the lizard brain.I'm actually slowly turning into one of those "finish the series before I start it" people myself. >_> Mostly because I've had several cases where I get super-enthused about a series, I follow it religiously for several years, and then gradually grow disenchanted due to the passage of time without plot resolution. Or because either I or the author have changed too much in the intervening time frame.

Anyway, I don't mind bigger books, but I have a definite respect for authors who know when to stop writing (Chris Wooding or Martha Wells come to mind here).

Mikhail wrote: "I seem to recall reading (possibly on Charlie Stross's blog), that one of the reasons for books getting bigger is that it allowed publishers to justify putting higher prices on them. The idea that ..."

Mikhail wrote: "I seem to recall reading (possibly on Charlie Stross's blog), that one of the reasons for books getting bigger is that it allowed publishers to justify putting higher prices on them. The idea that ..."I've heard that, too. This is favored because in reality, the material costs of the paper are a small fraction of the costs of publishing a book.

Mary wrote: "This is favored because in reality, the material costs of the paper are a small fraction of the costs of publishing a book. "

That makes sense, along with the weird consumer mental equation of bigger = more = better value.

That makes sense, along with the weird consumer mental equation of bigger = more = better value.

I understand that ebooks were a huge disrupting factor in all of this. Publishers trained readers to figure that a big, heavy hardcover was worth $25, while a paperback was worth about $7, and so people thought that they were mostly paying for the physical object (as opposed to paying more to get stuff earlier). Then when ebooks came along which had *no* physical object, there was much scrambling figuring out pricing, though it seems to have stabilized now.

I understand that ebooks were a huge disrupting factor in all of this. Publishers trained readers to figure that a big, heavy hardcover was worth $25, while a paperback was worth about $7, and so people thought that they were mostly paying for the physical object (as opposed to paying more to get stuff earlier). Then when ebooks came along which had *no* physical object, there was much scrambling figuring out pricing, though it seems to have stabilized now.

I confess, I'm part of that ebook problem. I don't see paying over $7 or $8 dollars for a book I can't sell, loan or store indefinitely.

Were I to actually have physical copies of all the books I read, my spaniel would have to take up mountain climbing to get around my house. So... also the problem. The only time I buy books these days is if I'm getting them signed.

Were I to actually have physical copies of all the books I read, my spaniel would have to take up mountain climbing to get around my house. So... also the problem. The only time I buy books these days is if I'm getting them signed.

Carol, do you go to movies, concerts, theater? Because you cant store or sell that after consumption as well. I know it is a head thing. But I came to understand that you pay the artistic value instead of a tangible good in the case of eBooks.

Carol, do you go to movies, concerts, theater? Because you cant store or sell that after consumption as well. I know it is a head thing. But I came to understand that you pay the artistic value instead of a tangible good in the case of eBooks.

I don't think movies, concerts, or theatre are good comparisons to books. You can go to a movie or you can wait for it to be older and rent it at home. The experience of seeing it on the big screen soon after its release is in the price. Theater and concerts are live performances, once in a lifetime experiences. I'm not saying that I'm unwilling to spend the money - if a book is good enough to keep I'll probably buy a physical copy of it. But with ebooks, even if you end up hating it all you can do is delete it from your device. You sell it, burn it, use it as a doorstop, or even donate it after your done. So it feels like it should cost less.

I don't think movies, concerts, or theatre are good comparisons to books. You can go to a movie or you can wait for it to be older and rent it at home. The experience of seeing it on the big screen soon after its release is in the price. Theater and concerts are live performances, once in a lifetime experiences. I'm not saying that I'm unwilling to spend the money - if a book is good enough to keep I'll probably buy a physical copy of it. But with ebooks, even if you end up hating it all you can do is delete it from your device. You sell it, burn it, use it as a doorstop, or even donate it after your done. So it feels like it should cost less.

Well, you can't store a concert or a movie showing, but you *can* buy an album, a DVD, and even for theater performances you can get soundtracks or videos. The literary equivalent here, I think, is not to books but to author events, public readings, and so forth.

Well, you can't store a concert or a movie showing, but you *can* buy an album, a DVD, and even for theater performances you can get soundtracks or videos. The literary equivalent here, I think, is not to books but to author events, public readings, and so forth.Funnily enough, now that I buy ebooks, I spend *more* money on books than I did before. Back in the day, I tended not to buy many books because (in addition to being a bankrupt student), I had nowhere to *put* them. So I went to the library a great deal, and while I love the idea of libraries dearly, and will defend them to the death.... lugging a duffel bag full of books from the central library across town back to my house was an ungodly annoyance. And then I'd not get past page ten in half of them because I am an aggravatingly picky reader.

Honestly, the combination of Goodreads + Amazon has probably tripled my reading amounts over the last few years.

I tend to agree with Naomi on paying more for an immersive experience versus a repeatable commodity. A concert etc. is created at a particular space point and time and cannot ever be replicated, even by recordings. I remember seeing The Grateful Dead in Shoreline, San Francisco, and last year paid a lot to see Paul Simon and Sting in NYC, and while they can't be stored/duplicated/shared, there's also no way to re-create it.

I know there's been a lot on the internet at various times, but to me, an e-book that costs the same as a printed book is ignoring the cost of the paper product and its ultimate re-usability. It's not like authors get more royalties with an ebook; it just goes to the publisher/amazon/etc. And I can't easily share an ebook, resell it to half-price books, donate it to my library for them to sell, leave it in a Little Free Library or leave it at the hospital for other people to use. Paperbooks can potentially be a community-wide resource.

I know there's been a lot on the internet at various times, but to me, an e-book that costs the same as a printed book is ignoring the cost of the paper product and its ultimate re-usability. It's not like authors get more royalties with an ebook; it just goes to the publisher/amazon/etc. And I can't easily share an ebook, resell it to half-price books, donate it to my library for them to sell, leave it in a Little Free Library or leave it at the hospital for other people to use. Paperbooks can potentially be a community-wide resource.