Divine Comedy + Decameron discussion

This topic is about

The Decameron

Boccaccio's Decameron

>

6/30-7/6: Third Day, Introduction & Stories 1-5

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

message 1:

by

Kris

(new)

-

added it

Apr 14, 2014 09:43AM

Mod

Mod

reply

|

flag

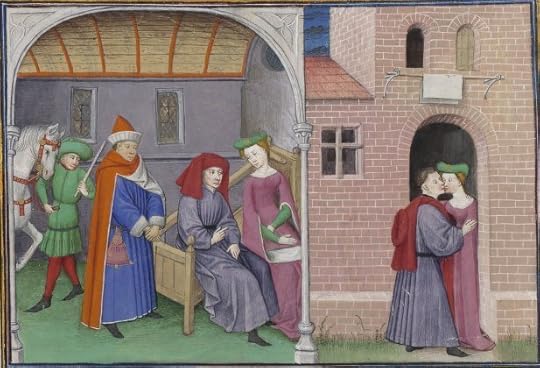

I'm falling behind but for those who are on schedule, here are some pretties to look at. :)

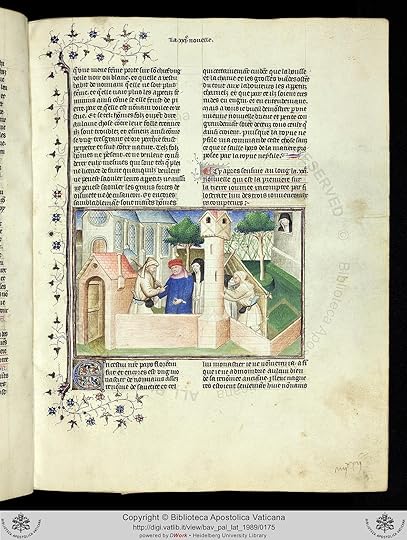

I'm falling behind but for those who are on schedule, here are some pretties to look at. :)Illustrations Day III - Story 1

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Masetto da Lamporecchio arrivant au monastère

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

Book Portrait wrote: "

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Masetto d..."

Thank you, BP.. I am somewhat behind, but should catch up during the week.

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Masetto d..."

Thank you, BP.. I am somewhat behind, but should catch up during the week.

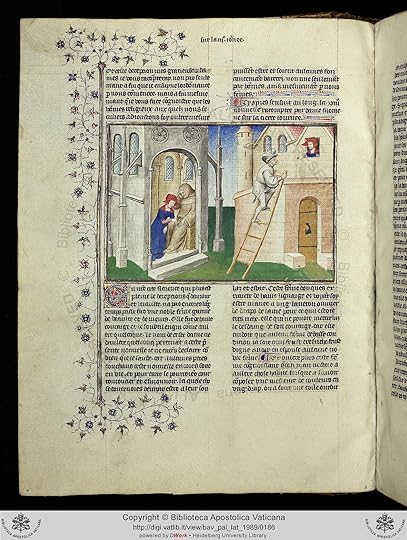

Illustrations - Day III Story 2

Illustrations - Day III Story 2

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Agilulf coupant une mèche du coupable

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

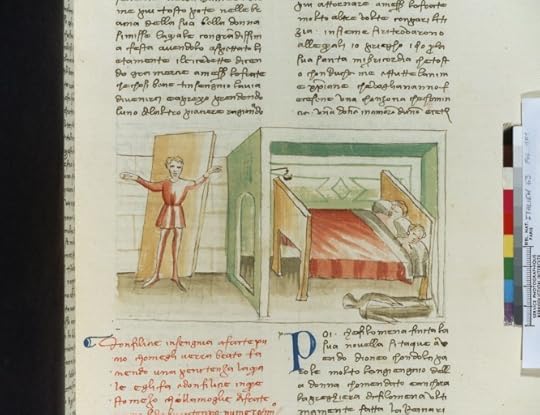

Illustrations - Day III Story 3

Illustrations - Day III Story 3

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Un amant pénétrant chez sa maîtresse

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

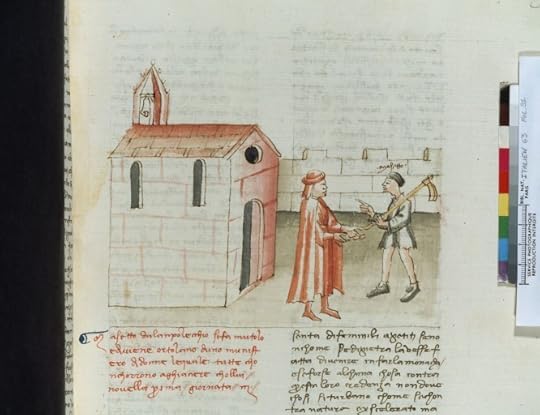

Illustrations - Day III Story 4

Illustrations - Day III Story 4

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Puccio di Rinieri abusé par Felice

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

Illustrations - Day III Story 5

Illustrations - Day III Story 5

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Zima parlant à l'épouse de Francesco

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

Book Portrait wrote: "Illustrations - Day III Story 2

Book Portrait wrote: "Illustrations - Day III Story 2http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Agilulf coupant une mèche du coupable

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

http://digi.vatlib.it/diglitData/imag..."

This illustration, with the locks cut and everybody sleeping in the same room, could perfectly fit with the Fabliaux! ^^

Yann wrote: "This illustration, with the locks cut and everybody sleeping in the same room, could perfectly fit with the Fabliaux! ^^"

Yann wrote: "This illustration, with the locks cut and everybody sleeping in the same room, could perfectly fit with the Fabliaux! ^^"This one makes me think of fairy tales, something like Little Thumb (Le Petit Poucet) or Bluebeard (Barbe Bleu)! But the idea of the erotic fabliaux is more promising! ^^

I like the one with the man "walking" on the tree branch to get in through the window (story 3).. He looks like a sleepwalker! ;)

Now I just have to read the stories to find out what really happens. :)

The ending of the First Story is quite amazing... Massetto proud that he has put the "horns" to no less than god...

!!!!!

!!!!!

Humor and Comedy in The Decameron and its Appeal to All Classes in Fourteenth-Century Italy

Giovanni Boccaccio's The Decameron tells tales of love in many forms, from the tragic to the comedic. The entertaining, and in many cases, joyful stories are unique in mid-fourteenth-century Italian literature, where the plague is one of the principle influences on writing and literary substance. Boccaccio uses his tales as a way to entertain all classes, and as a way to comment on various social issues that he feels are of concern to everyone. Because of this popular appeal, Boccaccio had to find away to produce humor and wit that the lower, as well as the upper classes would find funny. He accomplishes this through the use of religious and sexual humor. Boccaccio mocks all classes equally over the course of the various novellas, that allows every class to laugh at themselves just as much as laugh at everyone else.

The Catholic Church was an entity that nearly every Italian was connected to in some way. Thus, religious satire and humor was an essential way for Boccaccio to appeal to all classes of society. The first story in The Decameron actually drew its humor from a religious criticism, the issue of lying during a confession. The story tells of Ciapelletto, a notary who was know by many as a man who led a “wicked life”(Boccaccio, 1.1, Pg. 27). He is asked by a friend to do some business for him in Burgundy, which Ciapelletto agrees to do. Unfortunately, upon his arrival there, he falls fatally ill. When a friar is brought to him to hear his confessions, Ciapelletto lies to him and convinces the friar that he has led a virtuous life. After Ciapelletto's death, the friar delivers a sermon that makes everyone believe that Ciapelletto is a saint, and he is buried in a local chapel. The humor of this story appeals to all classes because many of those reading it would have been through a confession, and many may have also lied during confession themselves, and it portrays religious figures as gullible and overly blinded by faith, something not entirely false, but an aspect everyone could laugh at. This is also mocking the process of becoming a saint, that any man who claims he has led a pure life will be taken to be a “saintly man”(Boccaccio, 1.1, Pg. 35) and worshiped, regardless of anyone witnessing any miracles of substance, which was not an uncommon thought among people, for instance the sainthood of Thomas Aquinas.

Another aspect of the church that is even to this day ridiculed, is the corruption that is so common among church leaders. The second story that Boccaccio included in The Decameron revolves around this issue and the humor that stems from it. Abraham, a Jew, decides to travel to Rome to witness for himself the heart of the Catholic Church, and see if he would be willing to convert. To Giannotto di Civignì, a close friend of Abraham, who has been trying to convert in for years, this is a tragedy. He knows that once Abraham witnesses the corruption in Rome and “sees what foul and wicked lives the clergy lead, not only will he not become a Christian, but, if he ha already turned Christian, he would become a Jew again without fail”(Boccaccio, 1.2, Pg. 39). However, upon Abraham's return, Giannotto di Civignì is pleasantly surprised to hear that Abraham has chose to convert, claiming that only a religion that is able to spread, despite the corrupt hierarchy, could be the true word of God. While the personal connection to Giannotto di Civignì's original thought would bring a great deal of agreement and humorous entertainment to most readers, the final moral of the story also has a great connection to the readers. While not necessarily humor, except for maybe how unexpected the result was, Abraham's decision would give all Catholic readers a sense of pride in their faith, that it is strong amidst the corruption and the wickedness that plagues the church. The lowest and the highest class would have common feelings on this, and would be able to share same outlook on the ending of this story.

The religious aspects of the stories told in The Decameron provide appeal to both upper and lower classes because of the common religion, Catholicism, that many of the readers are a part of. Another aspect of these stories that has common appeal is the topic of sex and sexuality. Sex was not unique to any class and thus, any humor on that subject was enjoyed by all groups. In Boccaccio's fourth story, he begins to introduce this type of humor, coupling it with more religious humor. A monk, struck by a local girls beauty, convinces her to accompany him back to his room in the monastery. Unfortunately, the abbot observes this and is determined to catch the monk. However, the monk approaches the abbot and says that he is going to go and finish a task, and hands his key over to the abbot. The abbot then decides to enter the room himself and take advantage of the situation, still thinking that he is going to turn in the monk, while being able to indulge in pleasures of his own. The monk sees this and approaches the abbot. They both decide to keep quiet about the whole matter, and it is assumed that “they afterwards brought her back at regular intervals”(Boccaccio, 1.4, Pg. 48). Not only does this story mock the perceived promiscuity of clergy, but it also provides a humorous situation that does not apply directly to any class. Again, nearly every reader of this story would be able to find humor with the situation. It also reinforces the idea that the church hierarchy is corrupt and do not follow the protocol that they preach, as was also displayed in the second story.

Another instance of this coupling of religious criticism and sexual humor is in the first story of the third day. After the gardener of a convent quits, a man from his village decides to take the job, with the intention of playing dumb so that the nuns would think that they could get away with sleeping with him because “if he wanted to let the cat out of the bag, he wouldn't be able to”(Boccaccio, 3.1, Pg. 196). After having worked for awhile, this exact thing happens. Eventually, every nun at the convent, including the abbess is sleeping with him. He reveals that he is actually not dumb, and they decide to continue their relationships with him, with him as the steward, and he stays there for the rest of his days. This story is quite racy, and would be one of the only ones where any great deal of offense might be taken, especially among women. This story does not divide amongst classes, however, there is a good chance that men would enjoy this situation over women readers. Overall, the story is quite humorous because of the sneaky situation of the gardener getting exactly what he was looking for, and because of the high unlikeliness of that something like this could actually happen, especially the arrangement made in the end. But the sexual situation and religious connotations are the perfect way of appealing to both ends of the class spectrum.

Most of the stories that Boccaccio tells that include some sort of sexual humor, the actual act of sex is rather discreet and many things are implied. This is helpful, as it is less likely to offend people who are not as comfortable with sex. However, Boccaccio drastically changes from this pattern in the tenth story of the third day, and the sexual humor becomes much more graphic....

Giovanni Boccaccio's The Decameron tells tales of love in many forms, from the tragic to the comedic. The entertaining, and in many cases, joyful stories are unique in mid-fourteenth-century Italian literature, where the plague is one of the principle influences on writing and literary substance. Boccaccio uses his tales as a way to entertain all classes, and as a way to comment on various social issues that he feels are of concern to everyone. Because of this popular appeal, Boccaccio had to find away to produce humor and wit that the lower, as well as the upper classes would find funny. He accomplishes this through the use of religious and sexual humor. Boccaccio mocks all classes equally over the course of the various novellas, that allows every class to laugh at themselves just as much as laugh at everyone else.

The Catholic Church was an entity that nearly every Italian was connected to in some way. Thus, religious satire and humor was an essential way for Boccaccio to appeal to all classes of society. The first story in The Decameron actually drew its humor from a religious criticism, the issue of lying during a confession. The story tells of Ciapelletto, a notary who was know by many as a man who led a “wicked life”(Boccaccio, 1.1, Pg. 27). He is asked by a friend to do some business for him in Burgundy, which Ciapelletto agrees to do. Unfortunately, upon his arrival there, he falls fatally ill. When a friar is brought to him to hear his confessions, Ciapelletto lies to him and convinces the friar that he has led a virtuous life. After Ciapelletto's death, the friar delivers a sermon that makes everyone believe that Ciapelletto is a saint, and he is buried in a local chapel. The humor of this story appeals to all classes because many of those reading it would have been through a confession, and many may have also lied during confession themselves, and it portrays religious figures as gullible and overly blinded by faith, something not entirely false, but an aspect everyone could laugh at. This is also mocking the process of becoming a saint, that any man who claims he has led a pure life will be taken to be a “saintly man”(Boccaccio, 1.1, Pg. 35) and worshiped, regardless of anyone witnessing any miracles of substance, which was not an uncommon thought among people, for instance the sainthood of Thomas Aquinas.

Another aspect of the church that is even to this day ridiculed, is the corruption that is so common among church leaders. The second story that Boccaccio included in The Decameron revolves around this issue and the humor that stems from it. Abraham, a Jew, decides to travel to Rome to witness for himself the heart of the Catholic Church, and see if he would be willing to convert. To Giannotto di Civignì, a close friend of Abraham, who has been trying to convert in for years, this is a tragedy. He knows that once Abraham witnesses the corruption in Rome and “sees what foul and wicked lives the clergy lead, not only will he not become a Christian, but, if he ha already turned Christian, he would become a Jew again without fail”(Boccaccio, 1.2, Pg. 39). However, upon Abraham's return, Giannotto di Civignì is pleasantly surprised to hear that Abraham has chose to convert, claiming that only a religion that is able to spread, despite the corrupt hierarchy, could be the true word of God. While the personal connection to Giannotto di Civignì's original thought would bring a great deal of agreement and humorous entertainment to most readers, the final moral of the story also has a great connection to the readers. While not necessarily humor, except for maybe how unexpected the result was, Abraham's decision would give all Catholic readers a sense of pride in their faith, that it is strong amidst the corruption and the wickedness that plagues the church. The lowest and the highest class would have common feelings on this, and would be able to share same outlook on the ending of this story.

The religious aspects of the stories told in The Decameron provide appeal to both upper and lower classes because of the common religion, Catholicism, that many of the readers are a part of. Another aspect of these stories that has common appeal is the topic of sex and sexuality. Sex was not unique to any class and thus, any humor on that subject was enjoyed by all groups. In Boccaccio's fourth story, he begins to introduce this type of humor, coupling it with more religious humor. A monk, struck by a local girls beauty, convinces her to accompany him back to his room in the monastery. Unfortunately, the abbot observes this and is determined to catch the monk. However, the monk approaches the abbot and says that he is going to go and finish a task, and hands his key over to the abbot. The abbot then decides to enter the room himself and take advantage of the situation, still thinking that he is going to turn in the monk, while being able to indulge in pleasures of his own. The monk sees this and approaches the abbot. They both decide to keep quiet about the whole matter, and it is assumed that “they afterwards brought her back at regular intervals”(Boccaccio, 1.4, Pg. 48). Not only does this story mock the perceived promiscuity of clergy, but it also provides a humorous situation that does not apply directly to any class. Again, nearly every reader of this story would be able to find humor with the situation. It also reinforces the idea that the church hierarchy is corrupt and do not follow the protocol that they preach, as was also displayed in the second story.

Another instance of this coupling of religious criticism and sexual humor is in the first story of the third day. After the gardener of a convent quits, a man from his village decides to take the job, with the intention of playing dumb so that the nuns would think that they could get away with sleeping with him because “if he wanted to let the cat out of the bag, he wouldn't be able to”(Boccaccio, 3.1, Pg. 196). After having worked for awhile, this exact thing happens. Eventually, every nun at the convent, including the abbess is sleeping with him. He reveals that he is actually not dumb, and they decide to continue their relationships with him, with him as the steward, and he stays there for the rest of his days. This story is quite racy, and would be one of the only ones where any great deal of offense might be taken, especially among women. This story does not divide amongst classes, however, there is a good chance that men would enjoy this situation over women readers. Overall, the story is quite humorous because of the sneaky situation of the gardener getting exactly what he was looking for, and because of the high unlikeliness of that something like this could actually happen, especially the arrangement made in the end. But the sexual situation and religious connotations are the perfect way of appealing to both ends of the class spectrum.

Most of the stories that Boccaccio tells that include some sort of sexual humor, the actual act of sex is rather discreet and many things are implied. This is helpful, as it is less likely to offend people who are not as comfortable with sex. However, Boccaccio drastically changes from this pattern in the tenth story of the third day, and the sexual humor becomes much more graphic....

Toto wrote: "What was striking in this week's readings is the garden. Typical of all medieval gardens it is enclosed and is not for mere utilitarian purposes. With its lawn of fine grass, lemon trees, roses, t..."

I agree, Toto. That garden was most refreshing. But it made me think it was a reference to the Garden of Eden...., for as you say, it is paradise-like.

I agree, Toto. That garden was most refreshing. But it made me think it was a reference to the Garden of Eden...., for as you say, it is paradise-like.

ReemK10 (Paper Pills) wrote: "Humor and Comedy in The Decameron and its Appeal to All Classes in Fourteenth-Century Italy

Giovanni Boccaccio's The Decameron tells tales of love in many forms, from the tragic to the comedic...."

Thank you, Reem.. I will have to come back to this.. plenty of food for thought...

Giovanni Boccaccio's The Decameron tells tales of love in many forms, from the tragic to the comedic...."

Thank you, Reem.. I will have to come back to this.. plenty of food for thought...

Toto wrote: "What was striking in this week's readings is the garden. Typical of all medieval gardens it is enclosed and is not for mere utilitarian purposes. With its lawn of fine grass, lemon trees, roses, t..."

You bring up a very interesting point Toto. To add more about the garden of Boccaccio:

"The Garden of Boccaccio," a Critical Reading

From the outset of the poem, the garden of the Third Day of the Decameron as presented in Stothard's illustration (at right) is viewed by the speaker as an escape from the dreariness of daily life. Coleridge's narrator refers to the "dull continuous ache" (l. 9) he experienced prior to glancing at the illustration placed on his desk; Stothard's plate essentially brings him to Boccaccio's Garden, lifting his spirits and breaking his emotionless monotony. Like the members of the brigata, the speaker finds solace from what ails him in this Garden, "An Idyll, with Boccaccio's spirit warm" (l. 17). This first section of the poem also praises the genius of the order and the structure of the Decameron, which is "framed in the silent poesy of form" (l. 18).

The poem places a great deal of emphasis on the Garden as a passionate and emotional world of the young where the old might find some kind of nostalgic sentiment. Prior to his experience with the Garden, the speaker "Call'd on the Past for thought of glee or grief" (l. 6), longing for some kind of fervent feeling, be it pleasurable or tragic. It is interesting to note that, like the members of the brigata who enjoy tales which are often particularly down-hearted, Coleridge's speaker does not wish away tragedy but accepts it as a way to experience a powerful form of feeling. Having been unable to find this powerful feeling on his own, the speaker uses Boccaccio's Garden as a tool, calling upon "All spirits of power that most had stirr'd my thought / In selfless boyhood, on a new world tost / Of wonder, and in its own fancies lost" (ll. 28-30). He emphasizes a youthful sense of love and the search for a "form for love" (l. 32); this form can be viewed as the practice of storytelling, or as the series of ballads through which the brigata reveals to some extent its own tales of love.

The narrator writes that this youth to which he returns by way of Boccaccio's Garden "...lent a lustre to the earnest scan / of manhood, musing what and whence is man!" (ll. 33-34). The importance of this passage lies in the definition of youth in terms of a kind of search for meaning in life and thus implicitly attributes this search also to the members of the brigata who embody youthful love and pleasure in the Garden. These lines can be viewed as Coleridge's own interpretation of Boccaccio's text beyond its superficial string of stories, or as an indication that he believes there is more to the novellas than the recounting of anecdotes. Later in the poem, with the words "I see no longer! I myself am there, / sit on the ground-sward, and the banquet share" (ll. 64-65), he includes himself and, it can be argued, Boccaccio's general reader as a part of the brigata, experiencing the passions of the Garden and its tales. This connection seems to further emphasize the assertion of lines 33 and 34: the parallel, passionate quests for meaning that belong to the brigata and to the general reader, or Coleridge himself.

Coleridge goes on to juxtapose Philosophy and Poesy as differing forms of a similar concept; he defines Poesy as Philosophy "unconscious of herself" (l. 50), a "faery child" (l. 48) now a "matron ... of sober mien" (l. 46) in the poet's later life. The relationship that Coleridge creates between these two figures contributes to the reading presented here in that it allows the simultaneity of the youthful poesy that he praises in the Decameron and the deeper philosophical implications of the text.

"The Garden of Boccaccio" demonstrates a certain essentialist naturalism which in turn points to Coleridge's philosophical interpretation of the Decameron. He refers to the Garden as a place where "Nature makes her happy home with man" (l. 87). Lines 94 and 95 of the poem, which describe the experience of the Garden as "...the embrace and intertwine / of all with all in gay and twinkling dance," suggest an association of the natural world of Boccaccio's text with a kind of universal or cosmological interaction. This relationship of Nature with man's essential concerns further exposes Coleridge's intent to describe with his poem of praise a philosophical reading of the Decameron.

Coleridge ends the poem with a recognition of several of Boccaccio's sources - Maeonides (Homer) and Ovid, as well as ancient Greek mythology. He depicts the actual figure of "Boccace," kneeling in the Garden and "unfolding on his knees / the new-found roll of old Maeonides" (ll. 97-98), thus placing this continuation of tradition also within the Garden of philosophy and passion. With the words "Long be it mine to con thy mazy page" (l. 102), Coleridge identifies himself with this tradition, and places it upon himself to continue the spirited yet profound naturalism that Boccaccio's Garden and its sources have created.

You bring up a very interesting point Toto. To add more about the garden of Boccaccio:

"The Garden of Boccaccio," a Critical Reading

From the outset of the poem, the garden of the Third Day of the Decameron as presented in Stothard's illustration (at right) is viewed by the speaker as an escape from the dreariness of daily life. Coleridge's narrator refers to the "dull continuous ache" (l. 9) he experienced prior to glancing at the illustration placed on his desk; Stothard's plate essentially brings him to Boccaccio's Garden, lifting his spirits and breaking his emotionless monotony. Like the members of the brigata, the speaker finds solace from what ails him in this Garden, "An Idyll, with Boccaccio's spirit warm" (l. 17). This first section of the poem also praises the genius of the order and the structure of the Decameron, which is "framed in the silent poesy of form" (l. 18).

The poem places a great deal of emphasis on the Garden as a passionate and emotional world of the young where the old might find some kind of nostalgic sentiment. Prior to his experience with the Garden, the speaker "Call'd on the Past for thought of glee or grief" (l. 6), longing for some kind of fervent feeling, be it pleasurable or tragic. It is interesting to note that, like the members of the brigata who enjoy tales which are often particularly down-hearted, Coleridge's speaker does not wish away tragedy but accepts it as a way to experience a powerful form of feeling. Having been unable to find this powerful feeling on his own, the speaker uses Boccaccio's Garden as a tool, calling upon "All spirits of power that most had stirr'd my thought / In selfless boyhood, on a new world tost / Of wonder, and in its own fancies lost" (ll. 28-30). He emphasizes a youthful sense of love and the search for a "form for love" (l. 32); this form can be viewed as the practice of storytelling, or as the series of ballads through which the brigata reveals to some extent its own tales of love.

The narrator writes that this youth to which he returns by way of Boccaccio's Garden "...lent a lustre to the earnest scan / of manhood, musing what and whence is man!" (ll. 33-34). The importance of this passage lies in the definition of youth in terms of a kind of search for meaning in life and thus implicitly attributes this search also to the members of the brigata who embody youthful love and pleasure in the Garden. These lines can be viewed as Coleridge's own interpretation of Boccaccio's text beyond its superficial string of stories, or as an indication that he believes there is more to the novellas than the recounting of anecdotes. Later in the poem, with the words "I see no longer! I myself am there, / sit on the ground-sward, and the banquet share" (ll. 64-65), he includes himself and, it can be argued, Boccaccio's general reader as a part of the brigata, experiencing the passions of the Garden and its tales. This connection seems to further emphasize the assertion of lines 33 and 34: the parallel, passionate quests for meaning that belong to the brigata and to the general reader, or Coleridge himself.

Coleridge goes on to juxtapose Philosophy and Poesy as differing forms of a similar concept; he defines Poesy as Philosophy "unconscious of herself" (l. 50), a "faery child" (l. 48) now a "matron ... of sober mien" (l. 46) in the poet's later life. The relationship that Coleridge creates between these two figures contributes to the reading presented here in that it allows the simultaneity of the youthful poesy that he praises in the Decameron and the deeper philosophical implications of the text.

"The Garden of Boccaccio" demonstrates a certain essentialist naturalism which in turn points to Coleridge's philosophical interpretation of the Decameron. He refers to the Garden as a place where "Nature makes her happy home with man" (l. 87). Lines 94 and 95 of the poem, which describe the experience of the Garden as "...the embrace and intertwine / of all with all in gay and twinkling dance," suggest an association of the natural world of Boccaccio's text with a kind of universal or cosmological interaction. This relationship of Nature with man's essential concerns further exposes Coleridge's intent to describe with his poem of praise a philosophical reading of the Decameron.

Coleridge ends the poem with a recognition of several of Boccaccio's sources - Maeonides (Homer) and Ovid, as well as ancient Greek mythology. He depicts the actual figure of "Boccace," kneeling in the Garden and "unfolding on his knees / the new-found roll of old Maeonides" (ll. 97-98), thus placing this continuation of tradition also within the Garden of philosophy and passion. With the words "Long be it mine to con thy mazy page" (l. 102), Coleridge identifies himself with this tradition, and places it upon himself to continue the spirited yet profound naturalism that Boccaccio's Garden and its sources have created.

The Garden of Boccaccio

By Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772–1834)

OF late, in one of those most weary hours,

When life seems emptied of all genial powers,

A dreary mood, which he who ne’er has known

May bless his happy lot, I sate alone;

And, from the numbing spell to win relief, 5

Call’d on the Past for thought of glee or grief.

In vain! bereft alike of grief and glee,

I sate and cow’r’d o’er my own vacancy!

And as I watched the dull continuous ache,

Which, all else slumbering, seem’d alone to wake; 10

O Friend! long wont to notice yet conceal,

And soothe by silence what words cannot heal,

I but half saw that quiet hand of thine

Place on my desk this exquisite design,

Boccaccio’s Garden and its faery, 15

The love, the joyaunce, and the gallantry!

An Idyll, with Boccaccio’s spirit warm,

Framed in the silent poesy of form.

Like flocks a-down a newly-bathed steep

Emerging from a mist: or like a stream 20

Of music soft, that not dispels the sleep,

But casts in happier moulds the slumberer’s dream,

Gazed by an idle eye with silent might

The picture stole upon my inward sight.

A tremulous warmth crept gradual o’er my chest, 25

As though an infant’s finger touch’d my breast.

And one by one (I know not whence) were brought

All spirits of power that most had stirr’d my thought

In selfless boyhood, on a new world tost

Of wonder, and in its own fancies lost; 30

Or charm’d my youth, that, kindled from above,

Loved ere it loved, and sought a form for love;

Or lent a lustre to the earnest scan

Of manhood, musing what and whence is man!

Wild strain of Scalds, that in the sea-worn caves 35

Rehearsed their war-spell to the winds and waves;

Or fateful hymn of those prophetic maids,

That call’d on Hertha in deep forest glades;

Or minstrel lay, that cheer’d the baron’s feast;

Or rhyme of city pomp, of monk and priest, 40

Judge, mayor, and many a guild in long array,

To high-church pacing on the great saint’s day.

And many a verse which to myself I sang,

That woke the tear yet stole away the pang,

Of hopes which in lamenting I renew’d. 45

And last, a matron now, of sober mien,

Yet radiant still and with no earthly sheen,

Whom as a faery child my childhood woo’d

Even in my dawn of thought—Philosophy;

Though then unconscious of herself, pardie, 50

She bore no other name than Poesy;

And, like a gift from heaven, in lifeful glee,

That had but newly left a mother’s knee,

Prattled and play’d with bird and flower, and stone,

As if with elfin playfellows well known, 55

And life reveal’d to innocence alone.

Thanks, gentle artist! now I can descry

Thy fair creation with a mastering eye,

And all awake! And now in fixed gaze stand,

Now wander through the Eden of thy hand; 60

Praise the green arches, on the fountain clear

See fragment shadows of the crossing deer;

And with that serviceable nymph I stoop

The crystal from its restless pool to scoop.

I see no longer! I myself am there, 65

Sit on the ground-sward, and the banquet share.

’Tis I, that sweep that lute’s love-echoing strings,

And gaze upon the maid who gazing sings;

Or pause and listen to the tinkling bells

From the high tower, and think that there she dwells. 70

With old Boccaccio’s soul I stand possest,

And breathe an air like life, that swells my chest.

The brightness of the world, O thou once free,

And always fair, rare land of courtesy!

O Florence! with the Tuscan fields and hills 75

And famous Arno, fed with all their rills;

Thou brightest star of star-bright Italy!

Rich, ornate, populous, all treasures thine,

The golden corn, the olive, and the vine,

Fair cities, gallant mansions, castles old, 80

And forests, where beside his leafy hold

The sullen boar hath heard the distant horn;

Palladian palace with its storied halls;

Fountains, where Love lies listening to their falls;

Gardens, where flings the bridge its airy span, 85

And Nature makes her happy home with man:

Where many a gorgeous flower is duly fed

With its own rill, on its own spangled bed,

And wreathes the marble urn, or leans its head,

A mimic mourner, that with veil withdrawn 90

Weeps liquid gems, the presents of the dawn;—

Thine all delights, and every muse is thine;

And more than all, the embrace and intertwine

Of all with all in gay and twinkling dance!

’Mid gods of Greece and warriors of romance, 95

See! Boccace sits, unfolding on his knees

The new found roll of old Mæonides;

But from his mantle’s fold, and near the heart,

Peers Ovid’s Holy Book of Love’s sweet smart!

O all-enjoying and all-blending sage, 100

Long be it mine to con thy mazy page,

Where, half conceal’d, the eye of fancy views

Fauns, nymphs, and winged saints, all gracious to thy muse!

Still in thy garden let me watch their pranks,

And see in Dian’s vest between the ranks 105

Of the twin vines, some maid that half believes

The vestal fires, of which her lover grieves,

With that sly satyr peeping through the leaves!

By Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772–1834)

OF late, in one of those most weary hours,

When life seems emptied of all genial powers,

A dreary mood, which he who ne’er has known

May bless his happy lot, I sate alone;

And, from the numbing spell to win relief, 5

Call’d on the Past for thought of glee or grief.

In vain! bereft alike of grief and glee,

I sate and cow’r’d o’er my own vacancy!

And as I watched the dull continuous ache,

Which, all else slumbering, seem’d alone to wake; 10

O Friend! long wont to notice yet conceal,

And soothe by silence what words cannot heal,

I but half saw that quiet hand of thine

Place on my desk this exquisite design,

Boccaccio’s Garden and its faery, 15

The love, the joyaunce, and the gallantry!

An Idyll, with Boccaccio’s spirit warm,

Framed in the silent poesy of form.

Like flocks a-down a newly-bathed steep

Emerging from a mist: or like a stream 20

Of music soft, that not dispels the sleep,

But casts in happier moulds the slumberer’s dream,

Gazed by an idle eye with silent might

The picture stole upon my inward sight.

A tremulous warmth crept gradual o’er my chest, 25

As though an infant’s finger touch’d my breast.

And one by one (I know not whence) were brought

All spirits of power that most had stirr’d my thought

In selfless boyhood, on a new world tost

Of wonder, and in its own fancies lost; 30

Or charm’d my youth, that, kindled from above,

Loved ere it loved, and sought a form for love;

Or lent a lustre to the earnest scan

Of manhood, musing what and whence is man!

Wild strain of Scalds, that in the sea-worn caves 35

Rehearsed their war-spell to the winds and waves;

Or fateful hymn of those prophetic maids,

That call’d on Hertha in deep forest glades;

Or minstrel lay, that cheer’d the baron’s feast;

Or rhyme of city pomp, of monk and priest, 40

Judge, mayor, and many a guild in long array,

To high-church pacing on the great saint’s day.

And many a verse which to myself I sang,

That woke the tear yet stole away the pang,

Of hopes which in lamenting I renew’d. 45

And last, a matron now, of sober mien,

Yet radiant still and with no earthly sheen,

Whom as a faery child my childhood woo’d

Even in my dawn of thought—Philosophy;

Though then unconscious of herself, pardie, 50

She bore no other name than Poesy;

And, like a gift from heaven, in lifeful glee,

That had but newly left a mother’s knee,

Prattled and play’d with bird and flower, and stone,

As if with elfin playfellows well known, 55

And life reveal’d to innocence alone.

Thanks, gentle artist! now I can descry

Thy fair creation with a mastering eye,

And all awake! And now in fixed gaze stand,

Now wander through the Eden of thy hand; 60

Praise the green arches, on the fountain clear

See fragment shadows of the crossing deer;

And with that serviceable nymph I stoop

The crystal from its restless pool to scoop.

I see no longer! I myself am there, 65

Sit on the ground-sward, and the banquet share.

’Tis I, that sweep that lute’s love-echoing strings,

And gaze upon the maid who gazing sings;

Or pause and listen to the tinkling bells

From the high tower, and think that there she dwells. 70

With old Boccaccio’s soul I stand possest,

And breathe an air like life, that swells my chest.

The brightness of the world, O thou once free,

And always fair, rare land of courtesy!

O Florence! with the Tuscan fields and hills 75

And famous Arno, fed with all their rills;

Thou brightest star of star-bright Italy!

Rich, ornate, populous, all treasures thine,

The golden corn, the olive, and the vine,

Fair cities, gallant mansions, castles old, 80

And forests, where beside his leafy hold

The sullen boar hath heard the distant horn;

Palladian palace with its storied halls;

Fountains, where Love lies listening to their falls;

Gardens, where flings the bridge its airy span, 85

And Nature makes her happy home with man:

Where many a gorgeous flower is duly fed

With its own rill, on its own spangled bed,

And wreathes the marble urn, or leans its head,

A mimic mourner, that with veil withdrawn 90

Weeps liquid gems, the presents of the dawn;—

Thine all delights, and every muse is thine;

And more than all, the embrace and intertwine

Of all with all in gay and twinkling dance!

’Mid gods of Greece and warriors of romance, 95

See! Boccace sits, unfolding on his knees

The new found roll of old Mæonides;

But from his mantle’s fold, and near the heart,

Peers Ovid’s Holy Book of Love’s sweet smart!

O all-enjoying and all-blending sage, 100

Long be it mine to con thy mazy page,

Where, half conceal’d, the eye of fancy views

Fauns, nymphs, and winged saints, all gracious to thy muse!

Still in thy garden let me watch their pranks,

And see in Dian’s vest between the ranks 105

Of the twin vines, some maid that half believes

The vestal fires, of which her lover grieves,

With that sly satyr peeping through the leaves!

Kalliope wrote: I agree, Toto. That garden was most refreshing. But it made me think it was a reference to the Garden of Eden...., for as you say, it is paradise-like.

Analysis

In The Decameron's Third Day, First Story, Boccaccio uses the garden to portray a peaceful and natural surrounding, "within the garden, there is another, more secluded garden: an enclosed garden, a walled-in space whose most significant model is the garden of Love". . . ." According to Masetto, Boccaccio's introduction to the third day is, like Guillaume's poem. . . . a mockery of the religious quest for Eden" (qtd. in http://www.brown.edu/Departments/I…it...). During the renaissance, young women of limited financial means did not have many options in life. For instance, education was not mandatory and, therefore, women of lower economic status were probably denied education (http://www.brown.edu/Departments/I......). In addition, only wealthy women were expected to marry in order to pass on the inheritance to their offspring (women were not allowed to be property holders in this society). Therefore, if a young lady of limited means was not fortunate enough to marry, she faced the options of becoming a prostitute, a spinster or joining a convent. Thus, many poor women were sent to convents for these reasons. These women probably were not in the convent by choice.

Basically, the church allowed women two options, marriage and motherhood or virginity. The philosophy of the church was to prevent women from committing the "Sin of Eve" (qtd. in http://www.brown.edu/Departments/I…/d...), as Adam was tempted by Eve in the Garden of Eden. It was believed that women were more lustful than men and the Decameron website states, "men were more rational, active creatures and closer to the spiritual realm, while women were carnal by nature and thus more materialistic" (http://www.brown.edu/Departments/I…we...). Boccaccio uses the "seduction by silence" technique to show that sexuality is natural. Words are not always necessary in order to obtain sexual pleasure as with Masetto and the Nuns. (http://www.brown.edu/Departments/I…b/...)

In the film version of “The Decameron”, directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini, one of the earliest scenes depicts the bars at the door of the convent. These signify protection from the evils of society's sin (sexuality). The physical fortress of the convent emphasizes secrecy. The archways placed around the perimeter of the convent symbolize a confessional. This serves as a constant reminder to the nuns that, if they should sin in any way, they can confess and be forgiven. Masetto's ax is symbolic because it projects his knowledge about gardening and he uses the ax as a ploy to secure employment (Boccaccio 167).

The moral of the Third Day, First Story –- that the desire to explore human sexuality is natural and should not be repressed-- is further illustrated in another passage of “The Decameron.” Boccaccio uses the illustration of a father who kept his son living in the hills so that his carnal desires would never be awakened. One day the father took his son on a trip to the city. At once, the son saw a beautiful young woman, and asked his father "what are they called?" His father replied they are called "goslings" "not wanting his son to know the proper name"(Boccaccio 247). However, this did not deter the son from wanting to have a woman. The son lost all interest in the things familiar to him; such as caring for the animals and admiring the beautiful palaces. This proves that natural instincts control the body and we cannot deny the sexual desires that exist between men and women (Boccaccio 246-247). Boccaccio claims that:

A corrupt mind never understands a word in a healthy way!

And just as fitting words are of no use to a corrupt mind, so a

healthy mind cannot be contaminated by words which are not so

proper, any more than mud can dirty the rays of the sun or

earthly filth can mar the beauties of the skies (Boccaccio 686).

In his conclusion, Boccaccio states that: “The Decameron” was written for the "idle ladies", the ones who he believed needed to have something to read to pass their time while their men were out working. Since most women were uneducated, he addressed them on their level. (Boccaccio 687-688).

Society dictates what forms of sexual activity are acceptable. However, this story emphasizes that human sexuality is natural and cannot be restricted because of society's beliefs. People are tempted, conniving, curious, and weak. Placed in a situation where a choice has to be made human beings will react to the natural desire of their bodies.

Masetto is the main character and plays a central role in the story. He is a street-wise opportunist who sees a situation that he can exploit. He is clever and realizes that the Abbess might be suspicious of his good looks and youthful age. Therefore, Masetto decides to apply for the gardener’s position by posing as a deaf mute. As Nuto told Masetto: “God have better built sound of loins” (Boccacco 166). As a deaf mute, Masetto could not possibly be viewed as a threat to the convent. Because Masetto was deceptive in securing the gardening position, the reader can speculate that his intentions were not honorable. Needless to say, Masetto proves to be an excellent gardener and fulfills his extracurricular requirements with much enthusiasm. Masetto is eventually exhausted by his sexual escapades and verbally confesses to the Abbess. He dictates his terms for remaining at the convent and for keeping their secret. He further evidences his control of the situation by falsely telling the Abbess about “…an illness that took my speech from me, and tonight, for the first time, it was restored to me…” (Boccaccio 170). He eventually becomes “old and rich and a father, without ever having to bear the expense of bringing up his children, for he had been smart enough to make good use of this youth: having left with an ax on his shoulder, he returned affirming that this was the way Christ treated all those who put a pair of horns upon his crown” (Boccaccio 170-171).

The Abbess is a clever, scheming character who takes full advantage of the opportunity afforded by the presence of Masetto. She is very shrewd and tells the steward to dress Masetto in old clothing in order to make him less appealing to the nuns and to avoid the distraction his presence represents. The Abbess spends an inordinate amount of time with Masetto and deprives the other nuns of his sexual services. When she learns that Masetto is not a deaf mute, she proclaims his ability to speak a miracle and, in order to avoid scandal, agrees to Masetto’s terms. Of course, conceding to Masetto’s demands also ensured that the remained at the convent to sexually service the Abbess and the other nuns.

The other nuns in the convent are sexually curious about Masetto. The first nun who approaches him for intimacy was anxious to experience the pleasures of being with a man. Masetto presented the only opportunity for her to fulfill her dreams and she seized it. The second nun followed suit and, soon thereafter, all of the convent nuns had sexual relations with Masetto. The nuns believe that God will forgive them and do not seriously view their vow of virginity.

Both Steward and Nuto play minor roles in the story and little can be said about them. Nuto is depicted as exhausted and relieved to be away from the convent. The steward is described as an older man who is unsuspecting of the extracurricular activity at the convent.

Analysis

In The Decameron's Third Day, First Story, Boccaccio uses the garden to portray a peaceful and natural surrounding, "within the garden, there is another, more secluded garden: an enclosed garden, a walled-in space whose most significant model is the garden of Love". . . ." According to Masetto, Boccaccio's introduction to the third day is, like Guillaume's poem. . . . a mockery of the religious quest for Eden" (qtd. in http://www.brown.edu/Departments/I…it...). During the renaissance, young women of limited financial means did not have many options in life. For instance, education was not mandatory and, therefore, women of lower economic status were probably denied education (http://www.brown.edu/Departments/I......). In addition, only wealthy women were expected to marry in order to pass on the inheritance to their offspring (women were not allowed to be property holders in this society). Therefore, if a young lady of limited means was not fortunate enough to marry, she faced the options of becoming a prostitute, a spinster or joining a convent. Thus, many poor women were sent to convents for these reasons. These women probably were not in the convent by choice.

Basically, the church allowed women two options, marriage and motherhood or virginity. The philosophy of the church was to prevent women from committing the "Sin of Eve" (qtd. in http://www.brown.edu/Departments/I…/d...), as Adam was tempted by Eve in the Garden of Eden. It was believed that women were more lustful than men and the Decameron website states, "men were more rational, active creatures and closer to the spiritual realm, while women were carnal by nature and thus more materialistic" (http://www.brown.edu/Departments/I…we...). Boccaccio uses the "seduction by silence" technique to show that sexuality is natural. Words are not always necessary in order to obtain sexual pleasure as with Masetto and the Nuns. (http://www.brown.edu/Departments/I…b/...)

In the film version of “The Decameron”, directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini, one of the earliest scenes depicts the bars at the door of the convent. These signify protection from the evils of society's sin (sexuality). The physical fortress of the convent emphasizes secrecy. The archways placed around the perimeter of the convent symbolize a confessional. This serves as a constant reminder to the nuns that, if they should sin in any way, they can confess and be forgiven. Masetto's ax is symbolic because it projects his knowledge about gardening and he uses the ax as a ploy to secure employment (Boccaccio 167).

The moral of the Third Day, First Story –- that the desire to explore human sexuality is natural and should not be repressed-- is further illustrated in another passage of “The Decameron.” Boccaccio uses the illustration of a father who kept his son living in the hills so that his carnal desires would never be awakened. One day the father took his son on a trip to the city. At once, the son saw a beautiful young woman, and asked his father "what are they called?" His father replied they are called "goslings" "not wanting his son to know the proper name"(Boccaccio 247). However, this did not deter the son from wanting to have a woman. The son lost all interest in the things familiar to him; such as caring for the animals and admiring the beautiful palaces. This proves that natural instincts control the body and we cannot deny the sexual desires that exist between men and women (Boccaccio 246-247). Boccaccio claims that:

A corrupt mind never understands a word in a healthy way!

And just as fitting words are of no use to a corrupt mind, so a

healthy mind cannot be contaminated by words which are not so

proper, any more than mud can dirty the rays of the sun or

earthly filth can mar the beauties of the skies (Boccaccio 686).

In his conclusion, Boccaccio states that: “The Decameron” was written for the "idle ladies", the ones who he believed needed to have something to read to pass their time while their men were out working. Since most women were uneducated, he addressed them on their level. (Boccaccio 687-688).

Society dictates what forms of sexual activity are acceptable. However, this story emphasizes that human sexuality is natural and cannot be restricted because of society's beliefs. People are tempted, conniving, curious, and weak. Placed in a situation where a choice has to be made human beings will react to the natural desire of their bodies.

Masetto is the main character and plays a central role in the story. He is a street-wise opportunist who sees a situation that he can exploit. He is clever and realizes that the Abbess might be suspicious of his good looks and youthful age. Therefore, Masetto decides to apply for the gardener’s position by posing as a deaf mute. As Nuto told Masetto: “God have better built sound of loins” (Boccacco 166). As a deaf mute, Masetto could not possibly be viewed as a threat to the convent. Because Masetto was deceptive in securing the gardening position, the reader can speculate that his intentions were not honorable. Needless to say, Masetto proves to be an excellent gardener and fulfills his extracurricular requirements with much enthusiasm. Masetto is eventually exhausted by his sexual escapades and verbally confesses to the Abbess. He dictates his terms for remaining at the convent and for keeping their secret. He further evidences his control of the situation by falsely telling the Abbess about “…an illness that took my speech from me, and tonight, for the first time, it was restored to me…” (Boccaccio 170). He eventually becomes “old and rich and a father, without ever having to bear the expense of bringing up his children, for he had been smart enough to make good use of this youth: having left with an ax on his shoulder, he returned affirming that this was the way Christ treated all those who put a pair of horns upon his crown” (Boccaccio 170-171).

The Abbess is a clever, scheming character who takes full advantage of the opportunity afforded by the presence of Masetto. She is very shrewd and tells the steward to dress Masetto in old clothing in order to make him less appealing to the nuns and to avoid the distraction his presence represents. The Abbess spends an inordinate amount of time with Masetto and deprives the other nuns of his sexual services. When she learns that Masetto is not a deaf mute, she proclaims his ability to speak a miracle and, in order to avoid scandal, agrees to Masetto’s terms. Of course, conceding to Masetto’s demands also ensured that the remained at the convent to sexually service the Abbess and the other nuns.

The other nuns in the convent are sexually curious about Masetto. The first nun who approaches him for intimacy was anxious to experience the pleasures of being with a man. Masetto presented the only opportunity for her to fulfill her dreams and she seized it. The second nun followed suit and, soon thereafter, all of the convent nuns had sexual relations with Masetto. The nuns believe that God will forgive them and do not seriously view their vow of virginity.

Both Steward and Nuto play minor roles in the story and little can be said about them. Nuto is depicted as exhausted and relieved to be away from the convent. The steward is described as an older man who is unsuspecting of the extracurricular activity at the convent.

ReemK10 (Paper Pills) wrote: "Kalliope wrote: I agree, Toto. That garden was most refreshing. But it made me think it was a reference to the Garden of Eden...., for as you say, it is paradise-like.

Analysis

In The Decamer..."

In Medieval and early Renaissance iconography, an enclosed garden is also a symbol of virginity.

An Mary is often represented in such enclosed garden. This is Mary as "Hortus Conclusus".

There are many such images.

Boccaccio seems to be subverting this idea..

Analysis

In The Decamer..."

In Medieval and early Renaissance iconography, an enclosed garden is also a symbol of virginity.

An Mary is often represented in such enclosed garden. This is Mary as "Hortus Conclusus".

There are many such images.

Boccaccio seems to be subverting this idea..

Rowena wrote: "Thanks for the fascinating explanatory notes, Reem! I'm really enjoying this read:)"

Wonderful Rowena, so glad you're enjoying the stories!

Wonderful Rowena, so glad you're enjoying the stories!

Kalliope wrote: "ReemK10 (Paper Pills) wrote: "Kalliope wrote: I agree, Toto. That garden was most refreshing. But it made me think it was a reference to the Garden of Eden...., for as you say, it is paradise-like...."

Kalliope wrote: "ReemK10 (Paper Pills) wrote: "Kalliope wrote: I agree, Toto. That garden was most refreshing. But it made me think it was a reference to the Garden of Eden...., for as you say, it is paradise-like...."Thanks, that´s great! And as always, BP, for the illustrations!

Still dreadfully behind here, but about 3 this morning, I was thankful for the story of Tedaldo....it occurred to me that, while the Divine Comedy is a primer on how to get to heaven, this seems to be a primer on how to cheat, lie, and steal your way to the top! Nice to see a character with at least some redeeming qualities. Hope the subsequent days bring more of the same.

Linda wrote: "...And as always, BP, for the illustrations!..."

Linda wrote: "...And as always, BP, for the illustrations!..."You're welcome Linda! :)

*whispers* I'm actually lagging behind. I went back to read the second day, and then I'll have the third one to tackle... ^.^

Book Portrait wrote: "

*whispers* I'm actually lagging behind. I went back to read the second day, and then I'll have the third on..."

Do not worry... We will be waiting for you, and your pictorial arrows.

*whispers* I'm actually lagging behind. I went back to read the second day, and then I'll have the third on..."

Do not worry... We will be waiting for you, and your pictorial arrows.