Divine Comedy + Decameron discussion

This topic is about

The Decameron

Boccaccio's Decameron

>

7/7-7/13: Third Day, Stories 6-10 & Conclusion

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

message 1:

by

Kris

(new)

-

added it

Apr 14, 2014 09:42AM

Mod

Mod

reply

|

flag

For those who like to read the stories day by day, here's the rest of day 3. :)

For those who like to read the stories day by day, here's the rest of day 3. :)Illustrations - Day III Story 6

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Catella dupée par Ricciardo. Catella trompant son époux

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

Illustrations - Day III Story 7

Illustrations - Day III Story 7

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Tedaldo degli Elisei déguisé retrouvant Ermellina

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

Illustrations - Day III Story 8

Illustrations - Day III Story 8

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Confession de la femme de Ferondo. Ferondo au "purgatoire"

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

Illustrations - Day III Story 9

Illustrations - Day III Story 9

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Gillette de Narbonne devant son mari

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

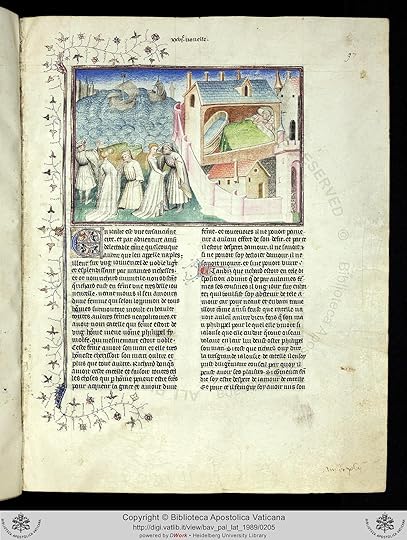

Illustrations - Day III Story 10

Illustrations - Day III Story 10

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Alibech et Rustico priant

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

Continuation of message 13

However, Boccaccio drastically changes from this pattern in the tenth story of the third day, and the sexual humor becomes much more graphic. In the story, Alibech, a young beautiful girl, goes to a man named Rustico, who is a monk to learn about how she could serve God. Rustico, overcome by lust, seduces her and convinces her that the best way to serve God is to help him put his “devil” into her “Hell”, as that will make the devil go away(Boccaccio, 3.10, Pg. 277). Eventually, Rustico tires of this, but Alibech is now troubled by her Hell, wanting to put the devil away. Though there is a pretty heavy metaphor that masks the actions that are taking place, it is still very clear as to what is going on. The story utilizes both religious and sexual humor, though it seems to be much more blunt in its execution, and is quite different from most of the others. While the idea that classes are not unbalanced is still present, the appeal of this story is a little more narrow to the audience that would enjoy its humor.

These stories that Boccaccio tells are important way that all the classes could be connected. The fact that The Decameron was written in the vernacular indicates that Boccaccio was hoping that everyone would have the opportunity to enjoy the stories and laugh at common humor. While some stories were slightly geared toward certain groups, overall there is a balance that doesn't cause to be turned off of the stories. The use of common issues that were found in society at that time and in that area made it more accessible to more people and allowed the jokes, puns, and criticisms to be more widely understood. Boccaccio created a highly entertaining and appealing piece of literature that was enjoyed by all manners of people and was capable of breaking class lines in its humor.

However, Boccaccio drastically changes from this pattern in the tenth story of the third day, and the sexual humor becomes much more graphic. In the story, Alibech, a young beautiful girl, goes to a man named Rustico, who is a monk to learn about how she could serve God. Rustico, overcome by lust, seduces her and convinces her that the best way to serve God is to help him put his “devil” into her “Hell”, as that will make the devil go away(Boccaccio, 3.10, Pg. 277). Eventually, Rustico tires of this, but Alibech is now troubled by her Hell, wanting to put the devil away. Though there is a pretty heavy metaphor that masks the actions that are taking place, it is still very clear as to what is going on. The story utilizes both religious and sexual humor, though it seems to be much more blunt in its execution, and is quite different from most of the others. While the idea that classes are not unbalanced is still present, the appeal of this story is a little more narrow to the audience that would enjoy its humor.

These stories that Boccaccio tells are important way that all the classes could be connected. The fact that The Decameron was written in the vernacular indicates that Boccaccio was hoping that everyone would have the opportunity to enjoy the stories and laugh at common humor. While some stories were slightly geared toward certain groups, overall there is a balance that doesn't cause to be turned off of the stories. The use of common issues that were found in society at that time and in that area made it more accessible to more people and allowed the jokes, puns, and criticisms to be more widely understood. Boccaccio created a highly entertaining and appealing piece of literature that was enjoyed by all manners of people and was capable of breaking class lines in its humor.

I am behind.. Just read story 6, but will catch up by the end of the week.

In this story 6 Boccaccio praises Naples (where he spent his youth) a couple of times.. I cannot quote because I am reading it in Spanish... (I may try and get the quote later on..).

I also enjoyed how he describes the local custom of people going to the beach to enjoy spending time there when it got very hot in that Southern part of Italy... we now have throngs of people streaming to the beaches...

This is a much later image of the Naples bay, but still it helps to try and get some sort of idea..

In this story 6 Boccaccio praises Naples (where he spent his youth) a couple of times.. I cannot quote because I am reading it in Spanish... (I may try and get the quote later on..).

I also enjoyed how he describes the local custom of people going to the beach to enjoy spending time there when it got very hot in that Southern part of Italy... we now have throngs of people streaming to the beaches...

This is a much later image of the Naples bay, but still it helps to try and get some sort of idea..

Book Portrait wrote: "For those who like to read the stories day by day, here's the rest of day 3. :)

Illustrations - Day III Story 6

.."

These are great.... so explicit with the bed... so naughty...

Illustrations - Day III Story 6

.."

These are great.... so explicit with the bed... so naughty...

Tale 8, with its mock Purgatory, reads very differently after the Divine Comedy where we learnt about this relatively new concept...

Alibech, Rustico, and the life of Saint Pelagia

A story in Boccaccio’s Decameron is set in the Egyptian desert of the desert fathers. The young hermit Rustico dwelling there unexpectedly encountered the beautiful girl Alibech. Dioneo, the narrator of this story, foretells the story as putting the Devil back into Hell:

I want to tell you how to do it. Perhaps you’ll even be able to save your souls once you’ve learned it. [1]

Dioneo’s story should be understood in the context of the Life of Saint Pelagia, an early Christian story of ascetic holiness. Both Dioneo’s story and the Life of Saint Pelagia affirm the natural goodness of human sexuality. They also recognize the human tendency toward deception and self-centeredness. At the beginning of the Decameron, Pampinea chartered the brigata with the fullness of good life:

We should go and stay on one of our various country estates, shunning the wicked practices of others like death itself, but having as much fun as possible, feasting and making merry, without ever trespassing the sign of reason in any way. [2]

In Dioneo’s story and the Life of Saint Pelagia, the sign of reason mirrors the sign of selfless self-giving in true love.

He who moves heaven and all of its stars

Made me, for His delight,

Refined and charming, graceful, too, and fair,

To give to lofty spirits here below

A certain sign of that

Beauty abiding ever in His sight.

But mortals imperfect,

Who can’t see what I am,

Find me unpleasing, nay, treat me with scorn. [3]

In the Life of Saint Pelagia, Pelagia’s well-cultivated physical beauty served as inspiration to a higher beauty. Pelagia was an actress, dancer, and courtesan. In the company of young men and wearing nothing but jewelry, Pelagia paraded by Bishop Nonnus and other bishops. Bishop Nonnus intently looked at her. He delighted in her beauty. Her beauty inspired him to cultivate beauty of the soul to please God the eternal lover. His fellow bishops lacked that lofty spirit. They scorned Pelagia’s obvious physical beauty. They thus deceived themselves and denied natural male sexuality.[4]

Saint Ursicinus, a hermit saint

The story of Alibech and Rustico plays these keys of asceticism and beauty, self-centeredness and deception. The story begins with unreason. Alibech was the fourteen-year-old daughter of a very rich man in the Muslim land of Tunisia. She was naive and not conscious of her own contradictory motivations:

She was not a Christian, but having heard how greatly the Christian faith and the service of God were praised by the numerous Christians living in the city, one day she asked one of them how God could be served best and with the least difficulty.[5]

Christians praising the Christian faith isn’t reasonably inspiring to non-Christians. A desire to best serve God isn’t consistent with a desire to serve God with the least difficulty. In any case, a Christian told Alibech that she could best serve God by becoming a holy recluse in the desert. Alibech unreasonably sought to do just that:

the following morning, moved not by a reasonable desire, but rather by a childish whim, she set out secretly for the Theban desert all by herself without letting anyone know what she was doing.

Alibech set out into the desert as an unholy fool.

Rustico led himself into temptation with Alibech. In the desert, Alibech went up to a holy man’s hut and asked him to teach her how to serve God. The hermit, with appreciation for his natural sexual desire for a beautiful girl, told her that he could not be her teacher. He advised her to seek someone more capable. Another hermit similarly advised Alibech. Then she came to Rustico. He was willing to put himself to the test. He took Alibech into his cell and made a bed for her from palm fronds. His holy resolve soon dissolved. He designed a scheme to gain consensual carnal knowledge of Alibech.

Rustico told Alibech that the most pleasing service to God is to put the Devil back into Hell. Rustico told the girl to do whatever he did. Then he took all his clothes off. He knelt down and had her kneel down just in front of him:

as they knelt in this way, and Rustico felt his desire growing hotter than ever at the sight of her beauty, the resurrection of the flesh took place. Staring at it in amazement, she said, “Rustico, what’s that thing I see sticking out in front of you, the thing I don’t have?”

Holy hermits aspired to put their flesh to death symbolically with ascetic practices. The resurrection of the flesh — Rustico’s genital erection — was a reversal of monastic asceticism.[6] Echoing the disparagement of men’s genitals in medieval European literature, Rustico described his penis as the Devil. He described Alibech’s vagina as Hell. With Alibech’s enthusiatic consent, Rustico put the Devil back into Hell. They went on to put the Devil back into Hell seven times, a virtuous number, before they rested for awhile. Alibech came to enjoy immensely putting the Devil back into Hell. At her insistence, they had sex even when Rustico didn’t want to. According to the United Nations’ judgment of criminality, Alibech raped Rustico repeatedly. Rustico became thin and exhausted. In a symbolic transfer of Alibech’s fiery lust, her father’s house burned down, killing him and all the family except for Alibech.

The story of Alibech and Rustico represents self-centeredness and deception. Personal whim propelled Alibech out into the desert to seek to serve the Christian understanding of God. After she experienced sex, she insistently demanded sex with no respect for Rustico’s exhaustion. Beneath Alibech’s expressed desire to serve God was her own self-centeredness. Rustico, on the other hand, betrayed his ascetic commitment as a monk and intentionally deceived Alibech with his story of putting the Devil back into Hell.

Beyond Alibech’s and Rustico’s problems of sexual desire are more important problems of self-centeredness and deception. True love, which can encompass sexual love, is impossible with deception and self-centeredness. That’s the higher meaning of Boccaccio’s story of Alibech and Rustico.[7]

A story in Boccaccio’s Decameron is set in the Egyptian desert of the desert fathers. The young hermit Rustico dwelling there unexpectedly encountered the beautiful girl Alibech. Dioneo, the narrator of this story, foretells the story as putting the Devil back into Hell:

I want to tell you how to do it. Perhaps you’ll even be able to save your souls once you’ve learned it. [1]

Dioneo’s story should be understood in the context of the Life of Saint Pelagia, an early Christian story of ascetic holiness. Both Dioneo’s story and the Life of Saint Pelagia affirm the natural goodness of human sexuality. They also recognize the human tendency toward deception and self-centeredness. At the beginning of the Decameron, Pampinea chartered the brigata with the fullness of good life:

We should go and stay on one of our various country estates, shunning the wicked practices of others like death itself, but having as much fun as possible, feasting and making merry, without ever trespassing the sign of reason in any way. [2]

In Dioneo’s story and the Life of Saint Pelagia, the sign of reason mirrors the sign of selfless self-giving in true love.

He who moves heaven and all of its stars

Made me, for His delight,

Refined and charming, graceful, too, and fair,

To give to lofty spirits here below

A certain sign of that

Beauty abiding ever in His sight.

But mortals imperfect,

Who can’t see what I am,

Find me unpleasing, nay, treat me with scorn. [3]

In the Life of Saint Pelagia, Pelagia’s well-cultivated physical beauty served as inspiration to a higher beauty. Pelagia was an actress, dancer, and courtesan. In the company of young men and wearing nothing but jewelry, Pelagia paraded by Bishop Nonnus and other bishops. Bishop Nonnus intently looked at her. He delighted in her beauty. Her beauty inspired him to cultivate beauty of the soul to please God the eternal lover. His fellow bishops lacked that lofty spirit. They scorned Pelagia’s obvious physical beauty. They thus deceived themselves and denied natural male sexuality.[4]

Saint Ursicinus, a hermit saint

The story of Alibech and Rustico plays these keys of asceticism and beauty, self-centeredness and deception. The story begins with unreason. Alibech was the fourteen-year-old daughter of a very rich man in the Muslim land of Tunisia. She was naive and not conscious of her own contradictory motivations:

She was not a Christian, but having heard how greatly the Christian faith and the service of God were praised by the numerous Christians living in the city, one day she asked one of them how God could be served best and with the least difficulty.[5]

Christians praising the Christian faith isn’t reasonably inspiring to non-Christians. A desire to best serve God isn’t consistent with a desire to serve God with the least difficulty. In any case, a Christian told Alibech that she could best serve God by becoming a holy recluse in the desert. Alibech unreasonably sought to do just that:

the following morning, moved not by a reasonable desire, but rather by a childish whim, she set out secretly for the Theban desert all by herself without letting anyone know what she was doing.

Alibech set out into the desert as an unholy fool.

Rustico led himself into temptation with Alibech. In the desert, Alibech went up to a holy man’s hut and asked him to teach her how to serve God. The hermit, with appreciation for his natural sexual desire for a beautiful girl, told her that he could not be her teacher. He advised her to seek someone more capable. Another hermit similarly advised Alibech. Then she came to Rustico. He was willing to put himself to the test. He took Alibech into his cell and made a bed for her from palm fronds. His holy resolve soon dissolved. He designed a scheme to gain consensual carnal knowledge of Alibech.

Rustico told Alibech that the most pleasing service to God is to put the Devil back into Hell. Rustico told the girl to do whatever he did. Then he took all his clothes off. He knelt down and had her kneel down just in front of him:

as they knelt in this way, and Rustico felt his desire growing hotter than ever at the sight of her beauty, the resurrection of the flesh took place. Staring at it in amazement, she said, “Rustico, what’s that thing I see sticking out in front of you, the thing I don’t have?”

Holy hermits aspired to put their flesh to death symbolically with ascetic practices. The resurrection of the flesh — Rustico’s genital erection — was a reversal of monastic asceticism.[6] Echoing the disparagement of men’s genitals in medieval European literature, Rustico described his penis as the Devil. He described Alibech’s vagina as Hell. With Alibech’s enthusiatic consent, Rustico put the Devil back into Hell. They went on to put the Devil back into Hell seven times, a virtuous number, before they rested for awhile. Alibech came to enjoy immensely putting the Devil back into Hell. At her insistence, they had sex even when Rustico didn’t want to. According to the United Nations’ judgment of criminality, Alibech raped Rustico repeatedly. Rustico became thin and exhausted. In a symbolic transfer of Alibech’s fiery lust, her father’s house burned down, killing him and all the family except for Alibech.

The story of Alibech and Rustico represents self-centeredness and deception. Personal whim propelled Alibech out into the desert to seek to serve the Christian understanding of God. After she experienced sex, she insistently demanded sex with no respect for Rustico’s exhaustion. Beneath Alibech’s expressed desire to serve God was her own self-centeredness. Rustico, on the other hand, betrayed his ascetic commitment as a monk and intentionally deceived Alibech with his story of putting the Devil back into Hell.

Beyond Alibech’s and Rustico’s problems of sexual desire are more important problems of self-centeredness and deception. True love, which can encompass sexual love, is impossible with deception and self-centeredness. That’s the higher meaning of Boccaccio’s story of Alibech and Rustico.[7]

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/All'...

[image error]

Shakespeare's acknowledged source for All's Well is Boccaccio's novella in the The Decameron Day 3, Story 9. The playwright probably knew the tale from William Painter's close translation of it in The Palace of Pleasure, published in 1566 and reprinted in 1569 and in 1575.

[image error]

Shakespeare's acknowledged source for All's Well is Boccaccio's novella in the The Decameron Day 3, Story 9. The playwright probably knew the tale from William Painter's close translation of it in The Palace of Pleasure, published in 1566 and reprinted in 1569 and in 1575.