Divine Comedy + Decameron discussion

This topic is about

The Decameron

Boccaccio's Decameron

>

10/6-10/12: Tenth Day, Introduction & Stories 1-5

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

message 1:

by

Kris

(new)

-

added it

Apr 14, 2014 09:28AM

Mod

Mod

reply

|

flag

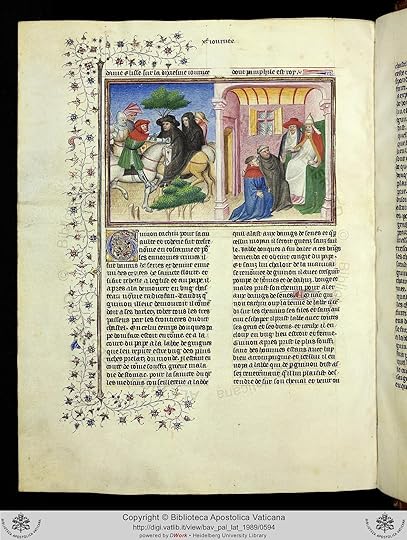

Illustrations - Day X Story 1

Illustrations - Day X Story 1

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Ruggieri de'Figiovanni et le roi

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

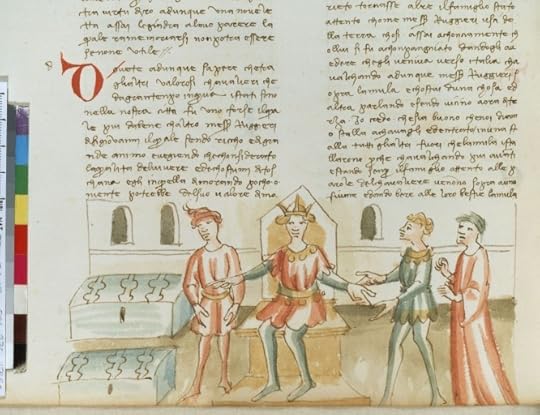

Illustrations - Day X Story 2

Illustrations - Day X Story 2

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Ghino di Tacco & l'abbé

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

Illustrations - Day X Story 3

Illustrations - Day X Story 3

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Mitridanes implorant son pardon

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

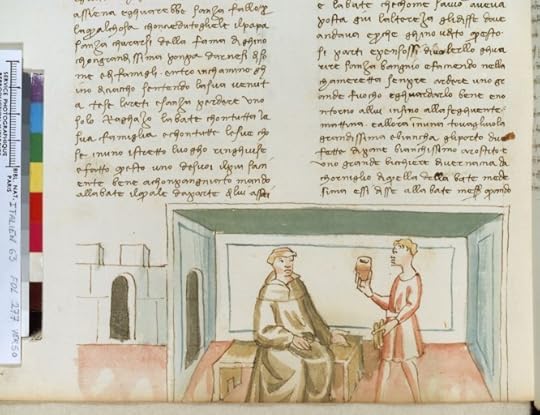

Illustrations - Day X Story 4

Illustrations - Day X Story 4

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Gentil Carisendi exhumant Catalina

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

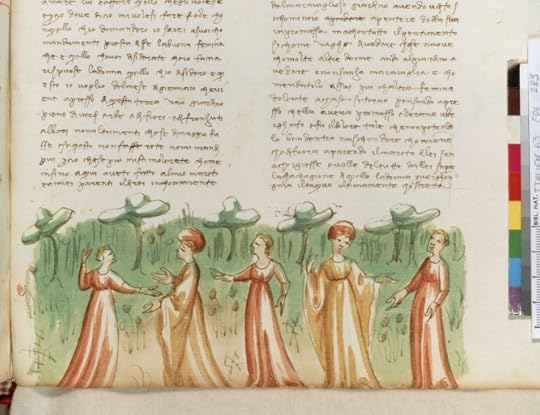

Illustrations - Day X Story 5

Illustrations - Day X Story 5

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1...

Dianora dans le jardin

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

(view spoiler)

So nice to see you here BP!!

First tale (X, 1)

Neifile's story is one of the most widely diffused ones in the entire collection. Its origins come from two different stories. The first part (the comparison of the king to a mule) comes from Busone de'Raffaelli da Gubbio's "Fortunatus Siculus," written about 1333 in Italian. The second part (concerning the caskets, known to English speakers from Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice) originates from about 800 AD from Joannes Damascensus's account of Barlaam and Josaphat and was written in Greek. Boccaccio most likely was inspired, though, by the Gesta Romanorum.

Barlaam and Josaphat is a legendary tale of two early Christian martyrs and saints, based ultimately on the life of the Buddha. It tells how an Indian king persecuted the Christian Church in his realm. When astrologers predicted that his own son would some day become a Christian, the king imprisoned the young prince Josaphat, who nevertheless met the hermit Saint Barlaam and converted to Christianity. After much tribulation the young prince's father accepted the true faith, turned over his throne to Josaphat, and retired to the desert to become a hermit. Josaphat himself later abdicated and went into seclusion with his old teacher Barlaam.

The tale can be traced from a 2nd to 4th century Sanskrit Mahayana Buddhist text, to a Manichee version, to the Arabic Kitab Bilawhar wa-Yudasaf (Book of Bilawhar and Yudasaf), current in Baghdad in the 8th century, from where it entered into Middle Eastern Christian circles before appearing in European versions. In the Middle Ages the two were treated as Christian saints, being entered in the Greek Orthodox calendar on 26 August,and in the Roman Martyrology in the Western Church as "Barlaam and Josaphat" on the date of 27 November.

Gesta Romanorum is a Latin collection of anecdotes and tales that was probably compiled about the end of the 13th century or the beginning of the 14th. It still possesses a two-fold literary interest, first as one of the most popular books of the time, and secondly as the source, directly or indirectly, of later literature, in Geoffrey Chaucer, John Gower, Giovanni Boccaccio, Thomas Hoccleve, William Shakespeare, and others.

Of its authorship nothing certain is known. It is conjecture to associate it either with the name of Helinandus or with that of Petrus Berchorius (Pierre Bercheure). It is debated whether it took its rise in England, Germany or France.

First tale (X, 1)

Neifile's story is one of the most widely diffused ones in the entire collection. Its origins come from two different stories. The first part (the comparison of the king to a mule) comes from Busone de'Raffaelli da Gubbio's "Fortunatus Siculus," written about 1333 in Italian. The second part (concerning the caskets, known to English speakers from Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice) originates from about 800 AD from Joannes Damascensus's account of Barlaam and Josaphat and was written in Greek. Boccaccio most likely was inspired, though, by the Gesta Romanorum.

Barlaam and Josaphat is a legendary tale of two early Christian martyrs and saints, based ultimately on the life of the Buddha. It tells how an Indian king persecuted the Christian Church in his realm. When astrologers predicted that his own son would some day become a Christian, the king imprisoned the young prince Josaphat, who nevertheless met the hermit Saint Barlaam and converted to Christianity. After much tribulation the young prince's father accepted the true faith, turned over his throne to Josaphat, and retired to the desert to become a hermit. Josaphat himself later abdicated and went into seclusion with his old teacher Barlaam.

The tale can be traced from a 2nd to 4th century Sanskrit Mahayana Buddhist text, to a Manichee version, to the Arabic Kitab Bilawhar wa-Yudasaf (Book of Bilawhar and Yudasaf), current in Baghdad in the 8th century, from where it entered into Middle Eastern Christian circles before appearing in European versions. In the Middle Ages the two were treated as Christian saints, being entered in the Greek Orthodox calendar on 26 August,and in the Roman Martyrology in the Western Church as "Barlaam and Josaphat" on the date of 27 November.

Gesta Romanorum is a Latin collection of anecdotes and tales that was probably compiled about the end of the 13th century or the beginning of the 14th. It still possesses a two-fold literary interest, first as one of the most popular books of the time, and secondly as the source, directly or indirectly, of later literature, in Geoffrey Chaucer, John Gower, Giovanni Boccaccio, Thomas Hoccleve, William Shakespeare, and others.

Of its authorship nothing certain is known. It is conjecture to associate it either with the name of Helinandus or with that of Petrus Berchorius (Pierre Bercheure). It is debated whether it took its rise in England, Germany or France.

Second tale (X, 2)

Ghino di Tacco, a real-life Italian outlaw.

Ghino di Tacco captures the Abbot of Cluny, cures him of a disorder of the stomach, and releases him. The abbot, on his return to the court of Rome, reconciles Ghino with Pope Boniface, and makes him prior of the Hospital.

Elissa narrates. Ghino di Tacco is the Italian equivalent of the English Robin Hood, with the difference that di Tacco was a real person whose deeds as a chief of a band of robbers passed into legend. He lived in the latter half of the 13th century. Boccaccio's tale, though, is one of many legends that grew up around him.

Ghino di Tacco, a real-life Italian outlaw.

Ghino di Tacco captures the Abbot of Cluny, cures him of a disorder of the stomach, and releases him. The abbot, on his return to the court of Rome, reconciles Ghino with Pope Boniface, and makes him prior of the Hospital.

Elissa narrates. Ghino di Tacco is the Italian equivalent of the English Robin Hood, with the difference that di Tacco was a real person whose deeds as a chief of a band of robbers passed into legend. He lived in the latter half of the 13th century. Boccaccio's tale, though, is one of many legends that grew up around him.

Fifth tale (II, 5)

Fiammetta tells this story which is actually a combination of two earlier tales. The beginning of the tale is first recorded in about 1228 by Courtois d'Arrass in his "Boivin de Provins." The portion of Andreuccio being trapped in the tomb of the archbishop and how he escapes comes from the Ephesian Tale by Xenophon of Ephesus, which was written in about 150 AD. That portion of the tale is so memorable that it was still being told as a true story in the cities and countryside of Europe in the early 20th century.

Fiammetta tells this story which is actually a combination of two earlier tales. The beginning of the tale is first recorded in about 1228 by Courtois d'Arrass in his "Boivin de Provins." The portion of Andreuccio being trapped in the tomb of the archbishop and how he escapes comes from the Ephesian Tale by Xenophon of Ephesus, which was written in about 150 AD. That portion of the tale is so memorable that it was still being told as a true story in the cities and countryside of Europe in the early 20th century.

ReemK10 (Paper Pills) wrote: "First tale (X, 1)

ReemK10 (Paper Pills) wrote: "First tale (X, 1)Neifile's story is one of the most widely diffused ones in the entire collection. Its origins come from two different stories. The first part (the c..."

It's amazing to read the history of some of these tales. Thanks for these posts Reem.

This week's section was one of my favorites. I particularly enjoyed the first two stories which played on the dissociation of the idea of Fortune and the power of Rulers.

I've enjoyed reading some from the last two days, some characters with redeeming qualities, finally! It's funny, bc I thought I was falling behind. I work with the old print text during the day/evening in the living room (not much time for that), and the kindle at night when insomnia hits. I realized last night that I'm actually ahead of the game, almost finished ( :) and :( ). A new record, for me and group reads!

I've enjoyed reading some from the last two days, some characters with redeeming qualities, finally! It's funny, bc I thought I was falling behind. I work with the old print text during the day/evening in the living room (not much time for that), and the kindle at night when insomnia hits. I realized last night that I'm actually ahead of the game, almost finished ( :) and :( ). A new record, for me and group reads!

Linda wrote: "I've enjoyed reading some from the last two days, some characters with redeeming qualities, finally! It's funny, bc I thought I was falling behind. I work with the old print text during the day/e..."

Way to go Linda! Isn't insomnia great for catching up on one's reading? With Ebola in the news, it makes you wonder about the plague happening at that time. This group of ten seem so unaffected by what is going on around them.

Way to go Linda! Isn't insomnia great for catching up on one's reading? With Ebola in the news, it makes you wonder about the plague happening at that time. This group of ten seem so unaffected by what is going on around them.

I'm almost finished too. I just have parts of day 3 left... At some point I'd like to read a biography of Boccaccio. I remember earlier comments saying that later in life he found faith and disowned the Decameron, which had probably brought him fame and recognition... If anything what stands out is the irrevence of the tales, particularly towards religious figures...

I'm almost finished too. I just have parts of day 3 left... At some point I'd like to read a biography of Boccaccio. I remember earlier comments saying that later in life he found faith and disowned the Decameron, which had probably brought him fame and recognition... If anything what stands out is the irrevence of the tales, particularly towards religious figures...

ReemK10 (Paper Pills) wrote: "Linda wrote: "I've enjoyed reading some from the last two days, some characters with redeeming qualities, finally! It's funny, bc I thought I was falling behind. I work with the old print text du..."

ReemK10 (Paper Pills) wrote: "Linda wrote: "I've enjoyed reading some from the last two days, some characters with redeeming qualities, finally! It's funny, bc I thought I was falling behind. I work with the old print text du..."My Kindle was a gift from friends, and I didn't think I'd like it. But I have to admit that, when the insomnia hits, it's easier to go back to sleep by its soft glow than it is with the lamp. And it's better for travel, too, since I can access email and take more books with less pounds.

Since Ebola's been a problem for at least 15 or 20 years, I'm sure there are those who say we've been the ones who were most oblivious--it's only now, when it hits our shores, that we're stepping on the gas pedal to test those treatments.

Book Portrait wrote: "I'm almost finished too. I just have parts of day 3 left... At some point I'd like to read a biography of Boccaccio. I remember earlier comments saying that later in life he found faith and disowne..."

Book Portrait wrote: "I'm almost finished too. I just have parts of day 3 left... At some point I'd like to read a biography of Boccaccio. I remember earlier comments saying that later in life he found faith and disowne..."I wonder, at what point did we elevate them to that pedestal, BP? In grad school, one of the things that I remember standing out from our discussion of "El libro de buen amor" was the priests' complaints that they were to lose their housekeepers, and on a Saturday. I would have skimmed right over that last bit. "Why", asked Prof Dutton, "does it seem to hurt them most that they lose them on a Saturday?!" So, it was apparent even then that they were human, after all. It would be interesting to see when that shift took place, when we started expecting them to commit to that, since in medieval times, it seems to have been common knowledge that they weren't.

Linda wrote: Since Ebola's been a problem for at least 15 or 20 years, I'm sure there are those who say we've been the ones who were most oblivious--it's only now, when it hits our shores, that we're stepping on the gas pedal to test those treatments.

You make an excellent point Linda! I do so respect that.

You make an excellent point Linda! I do so respect that.