Classics and the Western Canon discussion

The Magic Mountain

>

Week 1.1 Foreword and Chapter 1

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

@41 Zeke wrote: "...I am wondering as we form initial impressions of young Hans whether there is a distinction between "naive" and "callow?" And, if so, which is he? ..." See also @43.

@41 Zeke wrote: "...I am wondering as we form initial impressions of young Hans whether there is a distinction between "naive" and "callow?" And, if so, which is he? ..." See also @43.Zeke and Thorwald -- Thank you both for this discussion of "callow." The word had caught me off-guard as a description of Hans when I was reading (somewhere that I can't re-locate this morning, Woods's translation uses the word to describe our protagonist -- I'm spoiled, I want a Kindle edition so I can find it easily!). Anyway, the usages I have encountered previously had given the word negative connotations. As I read your discussion and do the dictionary check, I find it quite neutral in tone:

callow

1. a of a bird : lacking feathers : unfledged b : characteristic of or indicating immaturity < the callow down began to clothe my chin — John Dryden>

2. : marked by lack of adult sophistication, experience, perception, or judgment < a troop of newly arrived students, very young, pink and callow, followed nervously … at the director's heels — Aldous Huxley>

Middle English calu, calewe bald, from Old English calu; akin to Old High German kalo bald, Old Slavic golŭ naked

“Callow.” Webster's Third New International Dictionary, Unabridged. 2013. Web. 29 Mar. 2013.

Other terms used to describe Hans and to assign him the role of "quester" or of Parsifal, the "holy fool" also intrigue me at this point in the reading.

Other terms used to describe Hans and to assign him the role of "quester" or of Parsifal, the "holy fool" also intrigue me at this point in the reading. The introductory notes by A.S. Byatt in my copy refer to MM as "a parody of a Bildungsroman," which only adds to my present state of confusion. Incentive to keep reading. (Byatt also calls MM "a German myth" -- hmmm, now that means....?)

Another aspect of Castorp's character that we haven't mentioned yet is that he is an orphan.

Another aspect of Castorp's character that we haven't mentioned yet is that he is an orphan.Orphans are favorites of novelists. Consider, for just a few examples: Tom Jones; Oliver Twist; Jane Eyre; Becky Sharp (Vanity Fair); Dorothea and Celia Brooke (Middlemarch); Richard and Ada Carstairs (Bleak House; also Esther considers herself essentially an orphan for most of the book, but winds up not being); Kim; Pip (Great Expectations); Anne of Green Gables. And those are just a few.

Why are orphans so attractive to novelists? One reason, I think, is that they are not encumbered by parents so they have more freedom to make decisions about their life course. Another, perhaps more important reason, is that they have to make their own way through life in a way that children with parents to guide and assist them don't. Jane Eyre couldn't have undergone the same experiences if she had had loving parents to guide and assist her. And Oliver Twist is entirely centered around his being orphaned. In Vanity Fair, Becky is forgiven her overt attempts to snare Jos into marriage by the excuse that this is the usual role of mothers, but since she has no mother she has to make do by herself.

It's not clear yet how Castorp's being an orphan will affect the course of the novel, but I think it's worth noting, and keeping in mind as we read, that he follows in this noble tradition of orphan protagonists of great literature.

Interesting point Everyman. And, looking back to Lily @53, I would note that Parsifal is also an "orphan." (As, for that matter, is his predecessor in Wagner's imagination, Siegfried.)

At 18 Wendel wrote: "HC dreams about his cousin and dr. K. going down the mountain on a sleigh. .."

For what it's worth:

From Man and His Symbols with an introduction by Carl Jung:

"As a general rule, the unconscious aspect of any event is revealed to us in dreams, where it appears not as a rational thought but as a symbolic image" (5).

That one's unconscious is often aware of things that one is not aware of consciously.

Maybe Hans is unconsciously awAre that Joachim is more ill than Hans consciously wants to acknowledge.

Maybe it's something else that his unconscious is trying to tell him.

The book says that only the person dreaming is really in a position to interpret his dreams... Only the dreamer really knows what his symbols really mean to him.

Man and His Symbols

Man and His Symbols

For what it's worth:

From Man and His Symbols with an introduction by Carl Jung:

"As a general rule, the unconscious aspect of any event is revealed to us in dreams, where it appears not as a rational thought but as a symbolic image" (5).

That one's unconscious is often aware of things that one is not aware of consciously.

Maybe Hans is unconsciously awAre that Joachim is more ill than Hans consciously wants to acknowledge.

Maybe it's something else that his unconscious is trying to tell him.

The book says that only the person dreaming is really in a position to interpret his dreams... Only the dreamer really knows what his symbols really mean to him.

Man and His Symbols

Man and His Symbols

From p. 9 (Woods version, text is Jones translation.)

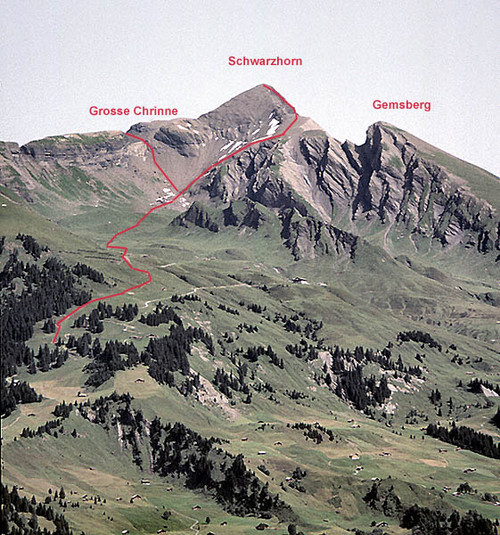

From p. 9 (Woods version, text is Jones translation.) A wind had sprung up, and made perceptible the chill of evening. “No, to speak frankly, I don’t find it so overpowering,” said Hans Castorp. “Where are the glaciers, and the snow peaks, and the gigantic heights you hear about? These things aren’t very high, it seems to me.” “Oh, yes, they are,” answered Joachim. “You can see the tree line almost everywhere, it is very sharply defined; the fir-trees leave off, and after that there is absolutely nothing but bare rock. And up there to the right of the Schwarzhorn, that tooth-shaped peak, there is a glacier—can’t you see the blue? It is not very large, but it is a glacier right enough, the Skaletta. Piz Michel and Tinzenhorn, in the notch—you can’t see them from here—have snow all the year round.” “Eternal snow,” said Hans Castorp.“Eternal snow, if you like. Yes, that’s all very high. But we are frightfully high ourselves: sixteen hundred metres above sea-level. That’s why the peaks don’t seem any higher.”

Schwarzhorn

Schwarzhorn from the west after a summer dusting of new snow. The right skyline is the SW Ridge.

http://www.summitpost.org/schwarzhorn... -- here for more. Not sure what the direction from Davos would be. 'Tis interesting that these are apparently not considered particularly difficult climbs relative to surrounding terrain -- there is a designation of "PreAlps"?

Thanks Lily! I had hoped you would find us some visuals ;)

Adelle wrote: "Thanks Lily! I had hoped you would find us some visuals ;)"

Adelle wrote: "Thanks Lily! I had hoped you would find us some visuals ;)"LOL! No Dali or Botticelli here, at least not yet. But I did add some links to Background for places named in the text above @57. Help, somebody, with Piz Michel?

I figured most are noting the early allusions here to "Eternal Snow" since anyone who has scanned the structure knows that we have a lengthy "Snow" section ahead in Chapter 6.

Lily wrote: "@41 Zeke wrote: "...I am wondering as we form initial impressions of young Hans whether there is a distinction between "naive" and "callow?" And, if so, which is he? ..." See also @43.

Lily wrote: "@41 Zeke wrote: "...I am wondering as we form initial impressions of young Hans whether there is a distinction between "naive" and "callow?" And, if so, which is he? ..." See also @43.Zeke and Th..."

I agree, "callow" is neutral, Hans Castorp is just young, he has all means to become a non-callow character!

I like your comparison to Parsifal - yes, good!

And again my comparison to Kaiser Wilhelm II: He, too, was not an evil person, just callow.

I dare to copy a citation from Wikipedia on Wilhelm II by Thomas Nipperdey who concludes that he was: "...gifted, with a quick understanding, sometimes brilliant, with a taste for the modern,—technology, industry, science—but at the same time superficial, hasty, restless, unable to relax, without any deeper level of seriousness, without any desire for hard work or drive to see things through to the end, without any sense of sobriety, for balance and boundaries, or even for reality and real problems, uncontrollable and scarcely capable of learning from experience, desperate for applause and success,—as Bismarck said early on in his life, he wanted every day to be his birthday—romantic, sentimental and theatrical, unsure and arrogant, with an immeasurably exaggerated self-confidence and desire to show off, a juvenile cadet, who never took the tone of the officers’ mess out of his voice, and brashly wanted to play the part of the supreme warlord, full of panicky fear of a monotonous life without any diversions, and yet aimless, pathological in his hatred against his English mother."

And when we hear of his problems with his mother and his father dying early (cancer) we have another analogy to our orphan Hans Castorp.

Thank you, Everyman and Wendel, for your explanations and suggestions re: the contagiousness of this disease.

Thank you, Everyman and Wendel, for your explanations and suggestions re: the contagiousness of this disease.I've been thinking that maybe most Sanatoriums were not as "laid back" in terms of letting healthy people visit and letting sick people go into the village, and perhaps Mann made it this way in The Magic Mountain as a metaphor for Germany and Europe at the time. Here is the description of The Magic Mountain on Goodreads:

"In this dizzyingly rich novel of ideas, Mann uses a sanatorium in the Swiss Alps, a community devoted exclusively to sickness, as a microcosm for Europe, which in the years before 1914 was already exhibiting the first symptoms of its own terminal irrationality. The Magic Mountain is a monumental work of erudition and irony, sexual tension and intellectual ferment, a book that pulses with life in the midst of death."

SO, I'm wondering if this is Mann's way of telling the readers that many Europeans were already exhibiting "irrational" or "sick" thoughts, and were spreading their thoughts (or their irrationality and sick ways of thinking) to perfectly "healthy" people who did not start thinking irrationally until they were exposed to it by other people.

I could be completely off. This is the first book by Thomas Mann that I've read, so I don't know whether or not he would present his ideas in this way. (In other words, creating a sanatorium that is as "open" as this one, just to prove his point about the issues in Europe at the time.)

Barbara wrote: "In other words, creating a sanatorium that is as "open" as this one, just to prove his point about the issues in Europe at the time...."

Barbara wrote: "In other words, creating a sanatorium that is as "open" as this one, just to prove his point about the issues in Europe at the time...."I think it is interesting to contrast what Mann set out to do with The Magic Mountain,: "a sort of satire on the tragedy just finished," i.e., Death in Venice, and what it eventually became. The opening setting was already sketched out in 1912, based on his visit to his wife at a similar sanatorium. It was to have "a simple-minded hero, in conflict between bourgeois decorum and macabre adventure." The project began to take on a life of its own, WWII occurred, MM was put aside, Mann "wrote The Reflections of a Non-Political Man, a work of painful introspection, in which I sought light upon my own views of European problems and conflicts. Actually, it became a preparation for the work of art itself; a preparation that grew to mammoth proportions and consumed vast amounts of time." He goes on to refer to MM as a "jest, a very serious jest," drawing parallels to Goethe's attitudes towards his Faust.

Hmmm -- stream of consciousness: David Foster Wallace, Infinite Jest. The tradition continues?

As to chapter one, obviously Hans is a bit nervous about catching TB as evidenced by his dreaming at the end that he was coughing "in that horribly pulpy manner" as well as startling from his sleep upon recalling that "the day before yesterday, someone had died" in that bed and "that wasn't the first time either" and his stepping back almost a full step when Dr. Krokoswki asked if he might need a physical. So he did have his concerns and indeed harbored concerns that Joachim might die as evidenced by his dream of Joachim sliding down on the bobsled (perhaps his concerns only surfaced in his dreams or sub conscience however but they were present on some level)

As to chapter one, obviously Hans is a bit nervous about catching TB as evidenced by his dreaming at the end that he was coughing "in that horribly pulpy manner" as well as startling from his sleep upon recalling that "the day before yesterday, someone had died" in that bed and "that wasn't the first time either" and his stepping back almost a full step when Dr. Krokoswki asked if he might need a physical. So he did have his concerns and indeed harbored concerns that Joachim might die as evidenced by his dream of Joachim sliding down on the bobsled (perhaps his concerns only surfaced in his dreams or sub conscience however but they were present on some level)

Barbara wrote: " I would think that only ill people are allowed in the sanatorium, and that they certainly can't leave and randomly walk around. To go and not only visit but to actually STAY at a sanitarium when you're perfectly healthy? How can the healthy people not eventually become ill???"

Barbara wrote: " I would think that only ill people are allowed in the sanatorium, and that they certainly can't leave and randomly walk around. To go and not only visit but to actually STAY at a sanitarium when you're perfectly healthy? How can the healthy people not eventually become ill???"I thought the same thing, but I read it as one of several things that are meant to be seen as not quite right. It is, indeed, as if we have entered a magic place where the rules have shifted. There is Hans's hot face and cold body, the idea that they would let him sleep as a healthy guest in the room in which a woman just died of a disease known to be contagious (thanks, Wendel), the odd comments of Dr. K. Most of all, I think this suspension of disbelief, if you will, was set up for me on the first page of the Foreword, where Mann (or the narrator, depending on how you read it) spends a circuitous paragraph on the past and time and "datedness" and then states, "But let us not intentionally obscure a clear state of affairs," though that is precisely what he has just done. In fact, he has just referred to "the problematic and uniquely double nature of that mysterious element [time]." To me, that seemed a signal that things to come might not be quite as they seemed.

On another note, I'm excited to be back with you after having last joined you for The Odyssey. This is a book I have been wanting to read, but not on my own!

Lily wrote: "Barbara wrote: "In other words, creating a sanatorium that is as "open" as this one, just to prove his point about the issues in Europe at the time...."

Lily wrote: "Barbara wrote: "In other words, creating a sanatorium that is as "open" as this one, just to prove his point about the issues in Europe at the time...."I think it is interesting to contrast what ..."

Lily, that's fascinating info. (I haven't been very good about reading all of the resource material that's provided here in the group, because I've been working like a mad-woman and I've also been fighting a losing battle with a horrible sinus infection.)

SO, your post, Message #62, is absolutely fantastic. I am not in the least surprised that Mann would refer to MM as "a jest, a very serious jest" because I'm definitely finding that it really does seem to be exactly that.

Is there any possibility that DFW named his book after Thomas Mann's comments on MM?

Sue wrote: "As to chapter one, obviously Hans is a bit nervous about catching TB as evidenced by his dreaming at the end that he was coughing "in that horribly pulpy manner" as well as startling from his sle..."

Sue wrote: "As to chapter one, obviously Hans is a bit nervous about catching TB as evidenced by his dreaming at the end that he was coughing "in that horribly pulpy manner" as well as startling from his sle..."Thanks Sue! I need to go back and reread the first few chapters. I'm halfway through the book at this point, but now I'm wishing that I waited to read it along with the group.

I do remember Hans' dreams and I remember that he was definitely uncomfortable about the fact that someone had just died in the room that he was given, but I didn't feel that he was afraid of catching this illness. Mann himself said that this is a book that should be read twice. He's probably right, because as I'm reading some of the posts here I'm realizing that I did miss out on some important points.

Kathy wrote: "Barbara wrote: " I would think that only ill people are allowed in the sanatorium, and that they certainly can't leave and randomly walk around. To go and not only visit but to actually STAY at a s..."

Kathy wrote: "Barbara wrote: " I would think that only ill people are allowed in the sanatorium, and that they certainly can't leave and randomly walk around. To go and not only visit but to actually STAY at a s..."Hi Kathy! Thanks for your fantastic post! Yes, "suspension of disbelief" -- My brain sort-of "forgot" about that concept!! Actually, I was thinking in terms of suspension of disbelief, but I wasn't consciously thinking of the TERM "suspension of disbelief." This may sound weird, but now that I can give an actual "term" to Mann's writing of MM, it all makes much more sense, so again, thank you!!!

Sue wrote: "As to chapter one, obviously Hans is a bit nervous about catching TB as evidenced by his dreaming at the end that he was coughing "in that horribly pulpy manner" as well as startling from his sle..."

Sue wrote: "As to chapter one, obviously Hans is a bit nervous about catching TB as evidenced by his dreaming at the end that he was coughing "in that horribly pulpy manner" as well as startling from his sle..."There is a comment in next week's reading which brings further light to this. But it will have to wait until next week to mention (as they say, stay tuned!)

Barbara wrote: "...Is there any possibility that DFW named his book after Thomas Mann's comments on MM? ..."

Barbara wrote: "...Is there any possibility that DFW named his book after Thomas Mann's comments on MM? ..."Barbara -- I don't know how far back the "conversations" go, as Eman and Great Books would put it, but I suspect David Wallace's Infinite Jest naming is more a nod to Goethe than to Mann, if to either. Mann wrote: "Goethe once called his Faust 'this very serious jest.'” No ego at all involved among these guys! They are good, and they know it! ;-)

Not to go on and on about TB, but I note those diagnosed with TB back in the day did go about their daily routines, taking "cures" or "rests" at times but going back into the mainstream lives until otherwise indicated. For instance, I am also reading about Nancy Astor currently, and her husband (Waldorf Astor) was a wealthy American who moved to England and was diagnosed with TB but ran for the House of Commons thereafter (1910) (albeit during his first run, he was "hindered by a serious attach of consumption in mid-campaign , so that he had to leave the field and rush up to Scotland with Nancy, to expose himself to cold fresh air" (he won a later bid). So indeed...it seems there was a good bit of mixing with those whom suffered and the healthy sorts!

Not to go on and on about TB, but I note those diagnosed with TB back in the day did go about their daily routines, taking "cures" or "rests" at times but going back into the mainstream lives until otherwise indicated. For instance, I am also reading about Nancy Astor currently, and her husband (Waldorf Astor) was a wealthy American who moved to England and was diagnosed with TB but ran for the House of Commons thereafter (1910) (albeit during his first run, he was "hindered by a serious attach of consumption in mid-campaign , so that he had to leave the field and rush up to Scotland with Nancy, to expose himself to cold fresh air" (he won a later bid). So indeed...it seems there was a good bit of mixing with those whom suffered and the healthy sorts!Further notable "consumptives" include inter alia: Descartes (54) , Voltaire (84), Watteau, the Brontes (29)(30)(39), Jane Austen (41), Edgar Allan Poe (40), Thoreau (45), Chekov (44), Balzac (52), Moliére (51). Source: Impact of Tuberculosis on History, Literature and Art by H.D. Chalke , Cambridge Journal Medical History 1962.

Sue wrote: "Not to go on and on about TB, but I note those diagnosed with TB back in the day did go about their daily routines, taking "cures" or "rests" at times but going back into the mainstream lives until..."

Sue wrote: "Not to go on and on about TB, but I note those diagnosed with TB back in the day did go about their daily routines, taking "cures" or "rests" at times but going back into the mainstream lives until..."I would add to your list George Orwell. Perhaps the 20th century author whose loss to TB I mourn most.

There have been several posts speculating on certain aspects of this novel searching for an underlying meaning of such things as the mountain, the high altitudes, and the different effects that time and space have on an individual. My concern is not so much as to why the author wrote this novel as much as it is why I should read it. The reason I find is that because on a cold spring day like yesterday, while an acquaintance of mine was in Chicago watching the White Sox game, I was sitting at home on top of The Magic Mountain meeting new people named Hans, Joachim, and Dr. Krokowski among others. The Sanatorium is a place with a haunting atmosphere and a mysterious aura about it. It reminds me of the setting in Dean Koontz's House of Thunder, for anyone who has read that book. I am not sure if Chapter 1 actually reveals that this is a TB clinic, I rather think that it does not. If not, I would classify that information as a type of spoiler, as it is much more interesting to read this part not knowing why these people are staying so long and what they are dying from. This is why I do not read the backs of novels or any existing synopsis, because the author is usually a more profound story teller than the publisher whose sole aim is to sell a book. I prefer knowing nothing about a book prior to reading it for myself. My motto is, "It is the author's story, let him tell it."

There have been several posts speculating on certain aspects of this novel searching for an underlying meaning of such things as the mountain, the high altitudes, and the different effects that time and space have on an individual. My concern is not so much as to why the author wrote this novel as much as it is why I should read it. The reason I find is that because on a cold spring day like yesterday, while an acquaintance of mine was in Chicago watching the White Sox game, I was sitting at home on top of The Magic Mountain meeting new people named Hans, Joachim, and Dr. Krokowski among others. The Sanatorium is a place with a haunting atmosphere and a mysterious aura about it. It reminds me of the setting in Dean Koontz's House of Thunder, for anyone who has read that book. I am not sure if Chapter 1 actually reveals that this is a TB clinic, I rather think that it does not. If not, I would classify that information as a type of spoiler, as it is much more interesting to read this part not knowing why these people are staying so long and what they are dying from. This is why I do not read the backs of novels or any existing synopsis, because the author is usually a more profound story teller than the publisher whose sole aim is to sell a book. I prefer knowing nothing about a book prior to reading it for myself. My motto is, "It is the author's story, let him tell it."

Jonathan wrote: "...I am not sure if Chapter 1 actually reveals that this is a TB clinic, I rather think that it does not.... I prefer knowing nothing about a book prior to reading it for myself. My motto is, 'It is the author's story, let him tell it.'"

Jonathan wrote: "...I am not sure if Chapter 1 actually reveals that this is a TB clinic, I rather think that it does not.... I prefer knowing nothing about a book prior to reading it for myself. My motto is, 'It is the author's story, let him tell it.'"Oh, dear me, Eman guilty of a spoiler? (see Msg 1) I have encountered few contributors so careful about the reading experiences of others as Everyman. (Incidentally, I had the same uncertainly whether "Chapter 1 actually reveals that this is a TB clinic" that you express. I still haven't double checked.)

Jonathan -- I know you were a part of the Victorians group discussion on discussing on these boards, but did you read the messages 40-44 here: http://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/1...

I am curious, if you "prefer knowing nothing about a book prior to reading it", how do you select books to read.

If one is going to participate in (online) discussions about a book one is reading, my own view is that one must expect to encounter others with very different views, both about the book and about reading, than one's own. The tradeoffs are there between reading alone or reading with or some other paradigm that one can create.

The House of Thunder by Dean Koontz

I think Jonathan is right that tuberculosis is not specifically stated, but we know almost immediately that HC is traveling to a sanatorium and that Joachim has a respiratory problem. It doesn't seem too much of a stretch, given the historical context, to say that the disease being treated is tuberculosis.

I think Jonathan is right that tuberculosis is not specifically stated, but we know almost immediately that HC is traveling to a sanatorium and that Joachim has a respiratory problem. It doesn't seem too much of a stretch, given the historical context, to say that the disease being treated is tuberculosis.

I had no idea it was a TB Clinic until joining in on the discussion. I liked the mysterious fates aspect of the victims and I think Mann purposely omitted the reason why everyone was there to add an element of mystery. That is funny what Lily said about Eman possibly being guilty of a spoiler, because he is obviously cautious to avoid it. I was just wondering if I missed something in chapter 1 or of everyone is getting this info from later in the book or from background information?

I had no idea it was a TB Clinic until joining in on the discussion. I liked the mysterious fates aspect of the victims and I think Mann purposely omitted the reason why everyone was there to add an element of mystery. That is funny what Lily said about Eman possibly being guilty of a spoiler, because he is obviously cautious to avoid it. I was just wondering if I missed something in chapter 1 or of everyone is getting this info from later in the book or from background information?

As to how I pick my books, that is a fair question. I used to read the backs, but I soon found out that those mini-summaries often divulge facts that are not otherwise encountered until 50 to a hundred pages into the book. There was a mystery I read where the back told who the victim was and she wasn't killed until halfway through. So, now I want to always start at page one and begin in utter darkness.

As to how I pick my books, that is a fair question. I used to read the backs, but I soon found out that those mini-summaries often divulge facts that are not otherwise encountered until 50 to a hundred pages into the book. There was a mystery I read where the back told who the victim was and she wasn't killed until halfway through. So, now I want to always start at page one and begin in utter darkness.I mostly read the classics and will randomly pick a book from a top 100 list or something like that. For example, this book was chosen and I already knew it was on the Novel 100 and some other lists, so I decided to go with it.

Jonathan wrote: "I had no idea it was a TB Clinic until joining in on the discussion. I liked the mysterious fates aspect of the victims and I think Mann purposely omitted the reason why everyone was there to add a..."

Jonathan wrote: "I had no idea it was a TB Clinic until joining in on the discussion. I liked the mysterious fates aspect of the victims and I think Mann purposely omitted the reason why everyone was there to add a..."I regret if my mentioning TB was a spoiler. We do know from the Foreword that this is early 1900s, we know in the first week's reading that it is a sanatorium in a community of sanatoriums where people die fairly often, both the former occupant of Room 34 and those whose bodies are sent down by sled from a higher sanatorium, we do know that it involves a prolonged recovery period, we do know that Joachim's illness is a lung illness in the upper lobe and that others also have lung issues, we do know that patients and non-ill visitors, spouses, parents, etc. are mingled together. While we aren't, in my translation, told specifically that it is TB, I don't know of any other illness of the time that would meet this same set of criteria. But if it did represent a spoiler for anyone, I do apologize for that.

(In fact, I'm not sure that were are told anywhere in the entire book specifically that it is TB. But we'll see.)

I was taking it as a more morbid theme. I was beginning to wonder if the patients were not being held against their will, especially when Joachim seemed to insinuate Hans would be there more than the three weeks he initially planned on. And, with the references to psychology I began to believe the patients were possibly brain washed into staying. So, when I found here that it is just a TB clinic I was surprised, that is all. I'm sure it is no big deal and not a cause for regret. That much of the setting and the plot is probably common knowledge and I was just not privy to it yet. I was more inundated by the numerous references to the disease, rather than the first post where it is mentioned. I was somewhat confused that the major topic of discussion was tuberculosis, when it hadn't been mentioned yet.

I was taking it as a more morbid theme. I was beginning to wonder if the patients were not being held against their will, especially when Joachim seemed to insinuate Hans would be there more than the three weeks he initially planned on. And, with the references to psychology I began to believe the patients were possibly brain washed into staying. So, when I found here that it is just a TB clinic I was surprised, that is all. I'm sure it is no big deal and not a cause for regret. That much of the setting and the plot is probably common knowledge and I was just not privy to it yet. I was more inundated by the numerous references to the disease, rather than the first post where it is mentioned. I was somewhat confused that the major topic of discussion was tuberculosis, when it hadn't been mentioned yet.

Jonathan wrote: "I was taking it as a more morbid theme. I was beginning to wonder if the patients were not being held against their will, especially when Joachim seemed to insinuate Hans would be there more than t..."

Jonathan wrote: "I was taking it as a more morbid theme. I was beginning to wonder if the patients were not being held against their will, especially when Joachim seemed to insinuate Hans would be there more than t..."You might be on to something there. That it is a TB clinic doesn't eliminate this possibility, in my opinion. What is it exactly that holds the patients there is something I've been wondering myself.

Gian wrote: "I've just finished the first chapter and I'm currently reading your posts before I start reading the next one. I've got very little to add for now, just that I think David Foster Wallace's Infinite..."

Gian wrote: "I've just finished the first chapter and I'm currently reading your posts before I start reading the next one. I've got very little to add for now, just that I think David Foster Wallace's Infinite..."Ah! Thank you! Makes sense. Probably should have known that, too -- may have heard it before. ;-( (And I am a bit sorry, because Goethe or Mann would have carried the legend/myth still further along the literary blood lines.)

I haven't read Infinite Jest and have only looked at excerpts of The Pale King, but am grateful for whomever suggested starting DFW with A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again .

Look forward to your comments on MM, Gian!

Just a note on the disease---we had a germ theory of disease in the era this novel is set, but I don't think the etiology of TB itself was elucidated until much later. Sort of like we know now that some cancers are caused by a virus, but we don't necessarily know which ones those are (cervical cancer is one). So characters in the novel might know that diseases in general are contagious, but do not necessarily know that TB is contagious.

Just a note on the disease---we had a germ theory of disease in the era this novel is set, but I don't think the etiology of TB itself was elucidated until much later. Sort of like we know now that some cancers are caused by a virus, but we don't necessarily know which ones those are (cervical cancer is one). So characters in the novel might know that diseases in general are contagious, but do not necessarily know that TB is contagious.

Hello fellow readers. I joined the group about a six weeks ago and followed along with the discussions to about Chapter 6 before deciding that I would buy the book and read it. I've read the first 90 pages and am now practicing with making comments according to the discussion heading(s, although with the benefit of having read your later comments.

Hello fellow readers. I joined the group about a six weeks ago and followed along with the discussions to about Chapter 6 before deciding that I would buy the book and read it. I've read the first 90 pages and am now practicing with making comments according to the discussion heading(s, although with the benefit of having read your later comments. I've thoroughly enjoyed all of your comments and would like to respond to many of them, but at this late juncture I think that is impractical so I've decided to include my comments in one post within the boundaries of the discussion thread. So, here goes:

HC is "the coddled scion of the family" leaving on a long trip - three weeks. He has "duties, interest, worries, and prospects". As he rides to the station, the narrator gives us a clue of things to come when HC arrives at his destination: "Space, like time, gives birth to forgetfulness, but does so by removing an individual from all relationships and placing him in a free and pristine state - indeed, in but a moment it can turn a pedant and philistine into something like a vagabond." Oooooh! is Mann telling us that HC, when he goes up to the cool fresh air of the mountain, will forget his life and obligations in Hamburg? Is he also telling us that HC is "one who makes a show of knowledge" (online dictionary definition of pedant) and "one who is guided by materialism and usually disdainful of intellectual values" (online dictionary definition of philistine, and one who leads an unsettled and irresponsible life (online dictionary definition of vagabond).

When he arrives at his destination and meets up with his cousin, Joachim, HC reveals that he knows very little about tuberculosis. (I don't know of any other disease where one stays at a sanatorium for treatment). (Edit: the last sentence of the first paragraph in "In the Restaurant" refers to a "tuberculosis sanatorium"). He asks his cousin if he will be returning to Hamburg with him after HC's visit "I really see nothing standing in your way". That treatment is a lengthy process and that sometimes people die - "they have to transport the bodies down by bobsled in the winter" - is apparently unknown to HC. "On bobsleds! And you can sit there and tell me that so calm and cool? You've become quite the cynic in the last five months." Later, in Room 34, HC hears someone cough "a cough unlike any that Hans Castorp had ever heard" -- he's learning about the disease. Not only that, HC is allowed to smoke! I'm amazed at him being allowed to smoke and the large quantity that he smokes around patients with a lung disease.

Then follows a discussion about Krokowski "He dissects the patients' psyches." I really don't understand this. Why would someone with tuberculosis need a psychiatrist, if that's Krokowski's profession? I wonder if psychiatry is the newest thing in medicine, and the rich, for surely only the rich stay in sanatoriums, can be sold this type of care?

As a side note, from my birth or soon thereafter, I lived in an apartment with my father, who had tuberculosis, together with my mother and two other family members. As a result, I have a natural immunity to the disease. While I don't know anything about the disease, I can only assume that one can be in the close company of someone with tuberculosis without contracting the disease.

I've also noticed that HC doesn't always pay attention to conversations, or maybe it's that he makes comments such as the magnificence of the mountains and then contradicts himself. In addition, he seems to laugh at inappropriate times. Is this one of those nervous laughs? Do they call it a Gallows laugh? Any thoughts on why he does this?

I'm not surprised by the quality of food in the restaurant, although the quantities seem large, but I am surprised that champagne and "Gruaud Larose", which I assume is some type of wine, is served. "They ordered a bottle of Gruaud Larose, which Hans Castorp sent back to be brought to room temperature." For some reason I find HC's action here distasteful, maybe it's because he's in a sanatorium where the "dining attendants" wouldn't necessarily be up on the social graces! I think it's snobbery, but he's about to be treated by Dr. Krokowski in the same manner that he treated the "attendant". How? The good doctor says "You see, I've never met a healthy person before." HC later wonders if he offended the doctor.

Incidentally, I wonder if the doctor is telling the truth about never having seen a healthy person before, or is it possible he's making a pitch for his specialty -- psychiatry?

I'm glad I'm reading this book, I just wish I'd read it when the group was reading it.

Elizabeth wrote: "Hello fellow readers. I joined the group about a six weeks ago and followed along with the discussions to about Chapter 6 before deciding that I would buy the book and read it. I've read the firs..."

Elizabeth! I'm so glad for ypu. My friend told me "Don't read that. It's so boring.". It was anything but. It was well-written and wonderfully engaging.

Interesting what you said about being able to live with tuberculois patients without developing the disease yourself. I had wondered why Behrens wasn't concerned.

Glad you're reading the book. People will, you know, read your comments!

Elizabeth! I'm so glad for ypu. My friend told me "Don't read that. It's so boring.". It was anything but. It was well-written and wonderfully engaging.

Interesting what you said about being able to live with tuberculois patients without developing the disease yourself. I had wondered why Behrens wasn't concerned.

Glad you're reading the book. People will, you know, read your comments!

Wonderful comments. I'm just sorry you couldn't have been with us as the discussion progressed; you obviously would have added a lot to it. But as I hope you know, the thread stay open indefinitely, so for sure keep posting. Your posts will definitely be read and enjoyed, even if people don't have the energy to interact with them as actively as we would have during the time of the read. But I for one, and I know many others, will read and appreciate them whenever you post them.

Wonderful comments. I'm just sorry you couldn't have been with us as the discussion progressed; you obviously would have added a lot to it. But as I hope you know, the thread stay open indefinitely, so for sure keep posting. Your posts will definitely be read and enjoyed, even if people don't have the energy to interact with them as actively as we would have during the time of the read. But I for one, and I know many others, will read and appreciate them whenever you post them.A few specific comments on your observations. A nice look at HC, and of close reading Mann (I found close reading a challenge given the richness of the text; there was nothing that one could safely overlook, which made it very hard, for me, at least, to know what to focus attention on). I had slid over descriptions of him such as "pedant" and "coddled scion," which you have been able to unpack and provide insight on.

I'm not at all surprised that smoking was allowed -- at the time, I think medical science didn't realize how harmful it is, and indeed some thought of it more as a healthy activity, both relaxing and stimulating (which seems a contradiction, but I think really isn't). Indeed, even in the 1950s doctors were recommending certain brands of cigarettes; of course, they were paid to, but I think also some (many?) of them didn't really see the danger yet.

I'm glad you picked up on Krokowski. I never did see very clearly what he actually did in his interactions with patients. (I hope it's not too much of a spoiler to note that you will find out that he did give regular lectures to the patients, but I won't go beyond that.) Psychiatry was, as you noted, fairly new, and was probably an interesting thing to do while you were isolated from most of humanity up there. But whether he practiced psychiatry as we think of it, or whether he was more concerned with helping people emotionally deal with their disease, their isolation, the limited company, etc., I never did find out. Perhaps you will, and if so will share your findings with us.

Anyhow, glad to have you with us -- and I hope that your continuing read of Magic Mountain won't prevent you also from reading Ovid's Metamorphoses along with the group!

You mention another aspect of TB that is relevant for our novel, the fact it took the lives of so many young adults. That is (I suppose) because it generally (but not always) took some years to develop, while many older people were immune from earlier contaminations.

I guess many of us whose family memory goes further back than 1950 must have memories like yours. In my case it was my mothers family, three of six children were sick. Two boys survived, my aunt died in 1946. Was it contagious? You bet it was.