The History Book Club discussion

UNITED STATES CONSTITUTION

>

THE AMENDMENTS

Yes, Bryan and thus we are back to the same question:

So, they passed the 25th Amendment. This does not answer why these presidents decided not to bring on a VP after they assumed office.

So, they passed the 25th Amendment. This does not answer why these presidents decided not to bring on a VP after they assumed office.

I found this in wikipedia:

Article I, Section 2, Clause 5 and Article II, Section 4 of the Constitution both authorize the House of Representatives to serve as a "grand jury" with the power to impeach high federal officials, including the President, for "treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors."

Similarly, Article I, Section 3, Clause 6 and Article II, Section 4 both authorize the Senate to serve as a court with the power to remove impeached officials from office, given a two-thirds vote to convict.

No Vice President has ever been impeached, least of all convicted; in 1973, Spiro Agnew came the closest.

Facing the possibility of impeachment after federal investigators probed his having allegedly received kickbacks from Maryland contractors when he was serving as County Executive of Baltimore County, he instead resigned and pleaded no contest to a single count of income-tax evasion.

Prior to ratification of the Twenty-fifth Amendment in 1967, no provision existed for filling a vacancy in the office of Vice President.

As a result, the Vice Presidency was left vacant 16 times, sometimes for nearly four years, until the next ensuing election and inauguration—eight times due to the death of the sitting president, resulting in the Vice Presidents becoming President; seven times due to the death of the sitting Vice President; and once due to the resignation of Vice President John C. Calhoun to become a senator.

Calhoun resigned because he had been dropped from the ticket by President Andrew Jackson in favor of Martin Van Buren. Already a lame duck Vice President, he was elected to the Senate by the South Carolina state legislature and resigned the Vice Presidency early to begin his Senate term because he believed he would have more power as a senator.

Since the adoption of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment, the office has been vacant twice while awaiting confirmation of the new Vice President by both houses of Congress.

The first such instance occurred in 1973 following the resignation of Spiro Agnew as Richard Nixon's Vice President. Gerald Ford was subsequently nominated by President Nixon and confirmed by Congress.

The second occurred 10 months later when Nixon resigned following the Watergate scandal and Ford assumed the Presidency.

The resulting Vice Presidential vacancy was filled by Nelson Rockefeller.

Ford and Rockefeller are the only two people to have served as Vice President without having been elected to the office.

I think this segment from wikipedia may answer Sam's question starting with the sentence in bold.

Article I, Section 2, Clause 5 and Article II, Section 4 of the Constitution both authorize the House of Representatives to serve as a "grand jury" with the power to impeach high federal officials, including the President, for "treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors."

Similarly, Article I, Section 3, Clause 6 and Article II, Section 4 both authorize the Senate to serve as a court with the power to remove impeached officials from office, given a two-thirds vote to convict.

No Vice President has ever been impeached, least of all convicted; in 1973, Spiro Agnew came the closest.

Facing the possibility of impeachment after federal investigators probed his having allegedly received kickbacks from Maryland contractors when he was serving as County Executive of Baltimore County, he instead resigned and pleaded no contest to a single count of income-tax evasion.

Prior to ratification of the Twenty-fifth Amendment in 1967, no provision existed for filling a vacancy in the office of Vice President.

As a result, the Vice Presidency was left vacant 16 times, sometimes for nearly four years, until the next ensuing election and inauguration—eight times due to the death of the sitting president, resulting in the Vice Presidents becoming President; seven times due to the death of the sitting Vice President; and once due to the resignation of Vice President John C. Calhoun to become a senator.

Calhoun resigned because he had been dropped from the ticket by President Andrew Jackson in favor of Martin Van Buren. Already a lame duck Vice President, he was elected to the Senate by the South Carolina state legislature and resigned the Vice Presidency early to begin his Senate term because he believed he would have more power as a senator.

Since the adoption of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment, the office has been vacant twice while awaiting confirmation of the new Vice President by both houses of Congress.

The first such instance occurred in 1973 following the resignation of Spiro Agnew as Richard Nixon's Vice President. Gerald Ford was subsequently nominated by President Nixon and confirmed by Congress.

The second occurred 10 months later when Nixon resigned following the Watergate scandal and Ford assumed the Presidency.

The resulting Vice Presidential vacancy was filled by Nelson Rockefeller.

Ford and Rockefeller are the only two people to have served as Vice President without having been elected to the office.

I think this segment from wikipedia may answer Sam's question starting with the sentence in bold.

Great work, Bentley. So, it seems that it was up to the President to decide if he wanted to fill the vacancy. I think we will have to look at each one to find an answer.

Great work, Bentley. So, it seems that it was up to the President to decide if he wanted to fill the vacancy. I think we will have to look at each one to find an answer.

Thanks Bryan, but it just showed me all of the things that I do not know about the Constitution and it would be interesting to look at the various problems faced. But I do not think that any of these Presidents had the power to fill the vacancy even if they wanted to.

I also forgot to copy and paste this part:

The Twenty-Fifth Amendment also made provisions for a replacement in the event that the Vice President died in office, resigned, or succeeded to the presidency. The original Constitution had no provision for selecting such a replacement, so the office of Vice President would remain vacant until the beginning of the next Presidential and Vice Presidential terms. This issue had arisen most recently with the assassination of then-President John Kennedy on November 22, 1963, and was rectified by Section 2 of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment.

Source: Wikipedia

I think what they are saying is that even if the President at that time wanted to have a vice president that there was no provision or process in place for him to have one. Therefore, they had to do without.

After the 25th amendment, as stated...there have only been two instances of a vacancy while awaiting Congressional confirmation (it takes both houses).

I do not think we can blame the founding fathers for this one because as you are aware originally the top vote getter got to be President and the next vote getter got to be vice president (and of course they were always from different parties). What fun. There was also a mechanism to run for VP at one point in time just like someone runs for Pres, So I guess we could say that the Congresses following the founding fathers messed things up. However, I think the problem from the Tyler presidency until the 25th amendment was passed (after President Kennedy was assassinated) was due to no Constitutional provision spelling out what could be done and what could not.

Putting into perspective the way the founding fathers originally saw this working would have meant that in the last election we would have had Obama as President and John McCain as VP - since he was the runner up vote getter (even though they are in competing parties). Of course, with everybody stirring the pot since the founding fathers came up with the Constitution and many Congresses since, things got a bit befuddled. The 25th amendment it seems tried to make sense of what should not have probably been changed in the first place. I see great possibilities for the way the founding fathers originally did things. That would have forced some kind of consensus on a regular and daily basis. I am sure that some folks would believe that this would mean gridlock; possibly but I think not. No worse than the climate that has been created in this country with the present situation.

I also forgot to copy and paste this part:

The Twenty-Fifth Amendment also made provisions for a replacement in the event that the Vice President died in office, resigned, or succeeded to the presidency. The original Constitution had no provision for selecting such a replacement, so the office of Vice President would remain vacant until the beginning of the next Presidential and Vice Presidential terms. This issue had arisen most recently with the assassination of then-President John Kennedy on November 22, 1963, and was rectified by Section 2 of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment.

Source: Wikipedia

I think what they are saying is that even if the President at that time wanted to have a vice president that there was no provision or process in place for him to have one. Therefore, they had to do without.

After the 25th amendment, as stated...there have only been two instances of a vacancy while awaiting Congressional confirmation (it takes both houses).

I do not think we can blame the founding fathers for this one because as you are aware originally the top vote getter got to be President and the next vote getter got to be vice president (and of course they were always from different parties). What fun. There was also a mechanism to run for VP at one point in time just like someone runs for Pres, So I guess we could say that the Congresses following the founding fathers messed things up. However, I think the problem from the Tyler presidency until the 25th amendment was passed (after President Kennedy was assassinated) was due to no Constitutional provision spelling out what could be done and what could not.

Putting into perspective the way the founding fathers originally saw this working would have meant that in the last election we would have had Obama as President and John McCain as VP - since he was the runner up vote getter (even though they are in competing parties). Of course, with everybody stirring the pot since the founding fathers came up with the Constitution and many Congresses since, things got a bit befuddled. The 25th amendment it seems tried to make sense of what should not have probably been changed in the first place. I see great possibilities for the way the founding fathers originally did things. That would have forced some kind of consensus on a regular and daily basis. I am sure that some folks would believe that this would mean gridlock; possibly but I think not. No worse than the climate that has been created in this country with the present situation.

Gerald Ford didn't leave the vice presidency vacant. He picked Nelson Rockefeller to fill it. I believe the way it works is that once a person has taken office as president, if the vice presidency is vacant he/she has the authority (and I'd say the duty) to nominate someone to fill the VP spot regardless of how he/she became president.

Gerald Ford didn't leave the vice presidency vacant. He picked Nelson Rockefeller to fill it. I believe the way it works is that once a person has taken office as president, if the vice presidency is vacant he/she has the authority (and I'd say the duty) to nominate someone to fill the VP spot regardless of how he/she became president.

Exactly, James. I think Wikipedia's meaning by vacant is that Nixon's caused a vacancy by getting Agnew to resign...but quickly filled it with Rockefeller.

Exactly, James. I think Wikipedia's meaning by vacant is that Nixon's caused a vacancy by getting Agnew to resign...but quickly filled it with Rockefeller.

Hi James, I think we figured it out with the twenty fifth amendment which changed everything.

Prior to that amendment; there was a problem. See message 107 where we did quote pretty much what you stated in 112. It certainly got confusing.

Prior to that amendment; there was a problem. See message 107 where we did quote pretty much what you stated in 112. It certainly got confusing.

You have to admit Haig's delivery didn't come off as clean as I am sure he would have liked. Sort of amusing at the time, and it was a goofy time.

You have to admit Haig's delivery didn't come off as clean as I am sure he would have liked. Sort of amusing at the time, and it was a goofy time.

This is an extremely interesting article on the First Amendment and how it protects a lot of things that for many people are absolutely outrageous and hurtful. It is a shame why these folks who show up at military personnel funerals and shout horrendous things to the families who are grieving over the lost of their loved one (husband, son or daughter) are allowed to do these things. But it seems it is all part of the First Amendment rights which protects the rights of all even those folks who are absolutely reprehensible.

The article is titled:

Why US government could not have stopped the Koran bonfire

By Katie Connolly

BBC News, Washington

The postponement of a small Florida church's plans to burn Korans was not a result of government intervention. Nor was it the the product of a legal challenge.

Pastor Terry Jones claims the issue was resolved through private negotiation with a New York imam, amid talk of repercussions for US troops abroad.

In fact, there was little the federal government could do but but watch - the US constitution rendered it almost powerless to stop the bonfire.

The United States stands apart from many other Western democracies in priding itself on a near absolute commitment to allowing freedom of speech.

It is enshrined in the First Amendment to the US constitution, alongside the right to free exercise of religion.

"Congress shall make no law… abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble," the relevant passage says.

Deeply ingrained in the American psyche, these rights are seen almost as a matter of national identity.

"The fundamental principle is that the government cannot restrict speech based on its content, even if an audience finds it offensive," says Prof Tim Zick, a First Amendment specialist from the William and Mary Law School.

"A speaker's autonomy to express himself - even in this deeply offensive manner - is, if not sacrosanct, then very highly regarded."

As a nation, he says, America has made a very different calculation about the protection of the speaker versus the dignity of the audience than many countries in Europe. America prioritises the autonomy of the speaker.

Denying the Holocaust, for example, is illegal in 16 European countries. Germany has banned the production and dissemination of pro-Nazi material.

But in the US, the courts have protected the rights of Nazis to express their views.

In one well-known case, the Supreme Court invoked the First Amendment to uphold the right of a neo-Nazi group to march through the predominantly Jewish town of Skokie, Illinois, and display swastikas.

Symbolic messages

The courts have decided that speech encompasses a wide array of non-verbal actions intended to communicate a message. That means symbolic acts such as the burning of a cross or Bible are protected under the free speech clause.

"Generally the first amendment protects offensive, repugnant and even hateful speech," says David Hudson, a scholar at the First Amendment Center in Washington DC.

Many outside America wonder why the US government could not have stopped Pastor Jones's bonfire.

That is why, in America, demonstrators can legally burn the American flag or the Ku Klux Klan can burn crosses, even though such activities can both outrage and offend.

"Even with respect to one of our most sacred symbols - the American flag - burning is lawful," says Mr Zick.

Such protections exist only up to a point. When speech crosses the line into threats which may directly incite violence or lawlessness, the First Amendment no longer applies.

Mr Hudson stresses that for legal purposes a threat must be imminent. "You have to show the immediacy of harm," he says.

For example, a Ku Klux Klansman may legally burn a cross on his own property as a political statement, regardless of how offensive his intentions may be to many.

But if he were to burn that cross or hang a noose at the house of a black American, the courts might consider his action an incitation of violence against that individual.

For that he could be arrested and tried.

'True threats'

The case of Ku Klux Klan cross-burning however is a specific exception. It has long historical associations with racism and violence against minorities in America.

Signs at Pastor Jones's church may be offensive, but they are not illegal

Burning sacred texts has not traditionally been linked with violence in the US.

"It would be difficult I think to categorise the burning of a book as a true threat," says Mr Hudson.

Nor could burning a Koran be considered a hate crime.

"The offence is to the object, which is obviously sacred, but it would not fall under hate crimes because it's not a crime affecting a person," says Mr Zick.

Pastor Jones has said that his bonfire was intended to send a message to Americans that they need to "stand up" to radical Islamists.

He would have burned books on private land, owned by his church. If he were to have moved his protest to outside a mosque, it is possible he could have been charged with disorderly conduct or breach of the peace.

But even then, Mr Zick notes, legal precedent means police are obliged to protect a person's right to speak.

If authorities had wished to clamp down on Pastor Jones, the only legal avenues would have been quite banal. He needed a permit to hold an outdoor fire in Florida, and even before the event was called off, he did not have one.

Source: BBC

The article is titled:

Why US government could not have stopped the Koran bonfire

By Katie Connolly

BBC News, Washington

The postponement of a small Florida church's plans to burn Korans was not a result of government intervention. Nor was it the the product of a legal challenge.

Pastor Terry Jones claims the issue was resolved through private negotiation with a New York imam, amid talk of repercussions for US troops abroad.

In fact, there was little the federal government could do but but watch - the US constitution rendered it almost powerless to stop the bonfire.

The United States stands apart from many other Western democracies in priding itself on a near absolute commitment to allowing freedom of speech.

It is enshrined in the First Amendment to the US constitution, alongside the right to free exercise of religion.

"Congress shall make no law… abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble," the relevant passage says.

Deeply ingrained in the American psyche, these rights are seen almost as a matter of national identity.

"The fundamental principle is that the government cannot restrict speech based on its content, even if an audience finds it offensive," says Prof Tim Zick, a First Amendment specialist from the William and Mary Law School.

"A speaker's autonomy to express himself - even in this deeply offensive manner - is, if not sacrosanct, then very highly regarded."

As a nation, he says, America has made a very different calculation about the protection of the speaker versus the dignity of the audience than many countries in Europe. America prioritises the autonomy of the speaker.

Denying the Holocaust, for example, is illegal in 16 European countries. Germany has banned the production and dissemination of pro-Nazi material.

But in the US, the courts have protected the rights of Nazis to express their views.

In one well-known case, the Supreme Court invoked the First Amendment to uphold the right of a neo-Nazi group to march through the predominantly Jewish town of Skokie, Illinois, and display swastikas.

Symbolic messages

The courts have decided that speech encompasses a wide array of non-verbal actions intended to communicate a message. That means symbolic acts such as the burning of a cross or Bible are protected under the free speech clause.

"Generally the first amendment protects offensive, repugnant and even hateful speech," says David Hudson, a scholar at the First Amendment Center in Washington DC.

Many outside America wonder why the US government could not have stopped Pastor Jones's bonfire.

That is why, in America, demonstrators can legally burn the American flag or the Ku Klux Klan can burn crosses, even though such activities can both outrage and offend.

"Even with respect to one of our most sacred symbols - the American flag - burning is lawful," says Mr Zick.

Such protections exist only up to a point. When speech crosses the line into threats which may directly incite violence or lawlessness, the First Amendment no longer applies.

Mr Hudson stresses that for legal purposes a threat must be imminent. "You have to show the immediacy of harm," he says.

For example, a Ku Klux Klansman may legally burn a cross on his own property as a political statement, regardless of how offensive his intentions may be to many.

But if he were to burn that cross or hang a noose at the house of a black American, the courts might consider his action an incitation of violence against that individual.

For that he could be arrested and tried.

'True threats'

The case of Ku Klux Klan cross-burning however is a specific exception. It has long historical associations with racism and violence against minorities in America.

Signs at Pastor Jones's church may be offensive, but they are not illegal

Burning sacred texts has not traditionally been linked with violence in the US.

"It would be difficult I think to categorise the burning of a book as a true threat," says Mr Hudson.

Nor could burning a Koran be considered a hate crime.

"The offence is to the object, which is obviously sacred, but it would not fall under hate crimes because it's not a crime affecting a person," says Mr Zick.

Pastor Jones has said that his bonfire was intended to send a message to Americans that they need to "stand up" to radical Islamists.

He would have burned books on private land, owned by his church. If he were to have moved his protest to outside a mosque, it is possible he could have been charged with disorderly conduct or breach of the peace.

But even then, Mr Zick notes, legal precedent means police are obliged to protect a person's right to speak.

If authorities had wished to clamp down on Pastor Jones, the only legal avenues would have been quite banal. He needed a permit to hold an outdoor fire in Florida, and even before the event was called off, he did not have one.

Source: BBC

The First Amendment was put in place to defend unpopular speech and while I agree that people need to use that right responsibly, we cannot shut people up just because we don't like what they're saying. We might not like it but we can't only obey the law when it's convenient for us to do so.

However, when they abuse that right and advocate breaking the law and/or are themselves breaking the law and/or sturring up hatred and violence then we can do something about it. But until then, we have to allow Terry Jones and others like him to say their say.

However, when they abuse that right and advocate breaking the law and/or are themselves breaking the law and/or sturring up hatred and violence then we can do something about it. But until then, we have to allow Terry Jones and others like him to say their say.

Yes Sam that is fortunately or unfortunately what the First Amendment says no matter how distasteful these folks are and/or how their speech seems to have an effect even on our military troops and the violence that they are subjected to abroad.

People do need to use that right responsibly but we can see in some instances that has not been the case.

People do need to use that right responsibly but we can see in some instances that has not been the case.

Our freedom of religion is something that non-Americans often don't understand. My aunt is from Iceland and when she first come to America and went to a church service she was horrified that a collection was taken to support the church.

Our freedom of religion is something that non-Americans often don't understand. My aunt is from Iceland and when she first come to America and went to a church service she was horrified that a collection was taken to support the church."Doesn't the church get enough from taxes?"

"There is no tax to support churches."

Then, they showed her a phonebook with all the churches and asked her how to divide up the taxes, if they existed.

As despicable as some of the actions of church representatives often are, it is an important aspect of American culture. By making everyone's religion equally free, we make our own religion freer, too.

I know many people who have chosen to immigrate to America because of freedom of religion. They chose not to go to France because they couldn't wear their religious parafinalia, but despite the fact that we hold their entire religion responsible for 9/11 they know that they will still be happier here, because of our first amendment.

Yes folks are always surprised by our separation of church and state.

You are right the First Amendment is a biggie.

You are right the First Amendment is a biggie.

Well it may be interesting to some that the First Amendment came up in a debate between two candidates in Delaware.

O'Donnell questions separation of church, state

http://news.yahoo.com/s/ap/20101019/a...

Here is the first amendment:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

O'Donnell questions separation of church, state

http://news.yahoo.com/s/ap/20101019/a...

Here is the first amendment:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

Just as a review: the first part of the amendment is called The Establishment Clause. Within the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment, there are two understood approaches by constitutional scholars and lawyers:

This part:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion

The Establishment Clause of the First Amendment refers to the first of several pronouncements in the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, stating that "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion".

The establishment clause has generally been interpreted to prohibit

1) the establishment of a national religion by Congress, or

2) the preference of one religion over another.

The first approach is called the "separation" or "no aid" interpretation, while the second approach is called the "non-preferential" or "accommodation" interpretation.

The accommodation interpretation prohibits Congress from preferring one religion over another, but does not prohibit the government's entry into religious domain to make accommodations in order to achieve the purposes of the Free Exercise Clause.

The clause itself was seen as a reaction to the Church of England, established as the official church of England and some of the colonies, during the colonial era.

Source: Wikipedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Establis...

This part:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion

The Establishment Clause of the First Amendment refers to the first of several pronouncements in the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, stating that "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion".

The establishment clause has generally been interpreted to prohibit

1) the establishment of a national religion by Congress, or

2) the preference of one religion over another.

The first approach is called the "separation" or "no aid" interpretation, while the second approach is called the "non-preferential" or "accommodation" interpretation.

The accommodation interpretation prohibits Congress from preferring one religion over another, but does not prohibit the government's entry into religious domain to make accommodations in order to achieve the purposes of the Free Exercise Clause.

The clause itself was seen as a reaction to the Church of England, established as the official church of England and some of the colonies, during the colonial era.

Source: Wikipedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Establis...

There is also the second part of that statement (called The Free Exercise Clause)

"Congress shall make no law … prohibiting the free exercise (of religion)" is called the free-exercise clause of the First Amendment. The free-exercise clause pertains to the right to freely exercise one’s religion. It states that the government shall make no law prohibiting the free exercise of religion.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Free_Exe...

"Congress shall make no law … prohibiting the free exercise (of religion)" is called the free-exercise clause of the First Amendment. The free-exercise clause pertains to the right to freely exercise one’s religion. It states that the government shall make no law prohibiting the free exercise of religion.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Free_Exe...

Federal judge: Terror law violates 1st Amendment

By LARRY NEUMEISTER | Associated Press – 5 hrs ago - May 17, 2012

NEW YORK (AP) — A judge on Wednesday struck down a portion of a law giving the government wide powers to regulate the detention, interrogation and prosecution of suspected terrorists, saying it left journalists, scholars and political activists facing the prospect of indefinite detention for exercising First Amendment rights.

U.S. District Judge Katherine Forrest in Manhattan said in a written ruling that a single page of the law has a "chilling impact on First Amendment rights." She cited testimony by journalists that they feared their association with certain individuals overseas could result in their arrest because a provision of the law subjects to indefinite detention anyone who "substantially" or "directly" provides "support" to forces such as al-Qaida or the Taliban. She said the wording was too vague and encouraged Congress to change it.

"An individual could run the risk of substantially supporting or directly supporting an associated force without even being aware that he or she was doing so," the judge said.

She said the law also gave the government authority to move against individuals who engage in political speech with views that "may be extreme and unpopular as measured against views of an average individual.

"That, however, is precisely what the First Amendment protects," Forrest wrote.

She called the fears of journalists in particular real and reasonable, citing testimony at a March hearing by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Christopher Hedges, who has interviewed al-Qaida members, conversed with members of the Taliban during speaking engagements overseas and reported on 17 groups named on a list prepared by the State Department of known terrorist organizations. He testified that the law has led him to consider altering speeches where members of al-Qaida or the Taliban might be present.

Hedges called Forrest's ruling "a tremendous step forward for the restoration of due process and the rule of law."

He said: "Ever since the law has come out, and because the law is so amorphous, the problem is you're not sure what you can say, what you can do and what context you can have."

Hedges was among seven individuals and one organization that challenged the law with a January lawsuit. The National Defense Authorization Act was signed into law in December, allowing for the indefinite detention of U.S. citizens suspected of terrorism. Wednesday's ruling does not affect another part of the law that enables the United States to indefinitely detain members of terrorist organizations, and the judge said the government has other legal authority it can use to detain those who support terrorists.

A message left Wednesday with a spokeswoman for government lawyers was not immediately returned.

Bruce Afran, a lawyer for the plaintiffs, called the ruling a "great victory for free speech."

"She's held that the government cannot subject people to indefinite imprisonment for engaging in speech, journalism or advocacy, regardless of how unpopular those ideas might be to some people," he said.

Attorney Carl Mayer, speaking for plaintiffs at oral arguments earlier this year, had noted that even President Barack Obama expressed reservations about certain aspects of the bill when he signed it into law.

After the ruling, Mayer called on the Obama administration to drop its decision to enforce the law. He also called on Congress to change it "to make it the law of the land that U.S. citizens are entitled to trial by jury. They are not subject to military detention, policing and tribunals, all the things we fought a revolution to make sure would never happen in this land."

The government had argued that the law did not change the practices of the United States since the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks and that the plaintiffs did not have legal standing to sue.

In March, the judge seemed sympathetic to the government's arguments until she asked a government attorney if he could assure the plaintiffs that they would not face detention under the law for their work.

She wrote Wednesday that the failure of the government to make such a representation required her to assume that government takes the position that the law covers "a wide swath of expressive and associational conduct."

Other Sources: Wikipedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Katherin...

Biographical Directory of Federal Judges

Forrest, Katherine Bolan

Born 1964 in New York, NY

Federal Judicial Service:

Judge, U.S. District Court, Southern District of New York

Nominated by Barack Obama on May 4, 2011, to a seat vacated by Jed S. Rakoff. Confirmed by the Senate on October 13, 2011, and received commission on October 17, 2011.

Education:

Wesleyan University, B.A., 1986

New York University School of Law, J.D., 1990

Professional Career:

Private practice, New York City, 1990-2010

Deputy assistant attorney general, U.S. Department of Justice, Washington, D.C., 2010-2011

Biography prior to appointment:

Katherine B. Forrest is a Deputy Assistant Attorney General in the Antitrust Division of the United States Department of Justice in Washington, D.C., a position she has held since October 2010. Prior to joining the Department of Justice, she worked at the law firm of Cravath, Swaine & Moore LLP in New York, handling an array of commercial litigation with a particular focus on antitrust, copyright, and digital media. Forrest worked at Cravath beginning in 1990, becoming a partner at the law firm in 1998. She received her J.D. in 1990 from the New York University School of Law and her B.A., with honors, from Wesleyan University in 1986.

By LARRY NEUMEISTER | Associated Press – 5 hrs ago - May 17, 2012

NEW YORK (AP) — A judge on Wednesday struck down a portion of a law giving the government wide powers to regulate the detention, interrogation and prosecution of suspected terrorists, saying it left journalists, scholars and political activists facing the prospect of indefinite detention for exercising First Amendment rights.

U.S. District Judge Katherine Forrest in Manhattan said in a written ruling that a single page of the law has a "chilling impact on First Amendment rights." She cited testimony by journalists that they feared their association with certain individuals overseas could result in their arrest because a provision of the law subjects to indefinite detention anyone who "substantially" or "directly" provides "support" to forces such as al-Qaida or the Taliban. She said the wording was too vague and encouraged Congress to change it.

"An individual could run the risk of substantially supporting or directly supporting an associated force without even being aware that he or she was doing so," the judge said.

She said the law also gave the government authority to move against individuals who engage in political speech with views that "may be extreme and unpopular as measured against views of an average individual.

"That, however, is precisely what the First Amendment protects," Forrest wrote.

She called the fears of journalists in particular real and reasonable, citing testimony at a March hearing by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Christopher Hedges, who has interviewed al-Qaida members, conversed with members of the Taliban during speaking engagements overseas and reported on 17 groups named on a list prepared by the State Department of known terrorist organizations. He testified that the law has led him to consider altering speeches where members of al-Qaida or the Taliban might be present.

Hedges called Forrest's ruling "a tremendous step forward for the restoration of due process and the rule of law."

He said: "Ever since the law has come out, and because the law is so amorphous, the problem is you're not sure what you can say, what you can do and what context you can have."

Hedges was among seven individuals and one organization that challenged the law with a January lawsuit. The National Defense Authorization Act was signed into law in December, allowing for the indefinite detention of U.S. citizens suspected of terrorism. Wednesday's ruling does not affect another part of the law that enables the United States to indefinitely detain members of terrorist organizations, and the judge said the government has other legal authority it can use to detain those who support terrorists.

A message left Wednesday with a spokeswoman for government lawyers was not immediately returned.

Bruce Afran, a lawyer for the plaintiffs, called the ruling a "great victory for free speech."

"She's held that the government cannot subject people to indefinite imprisonment for engaging in speech, journalism or advocacy, regardless of how unpopular those ideas might be to some people," he said.

Attorney Carl Mayer, speaking for plaintiffs at oral arguments earlier this year, had noted that even President Barack Obama expressed reservations about certain aspects of the bill when he signed it into law.

After the ruling, Mayer called on the Obama administration to drop its decision to enforce the law. He also called on Congress to change it "to make it the law of the land that U.S. citizens are entitled to trial by jury. They are not subject to military detention, policing and tribunals, all the things we fought a revolution to make sure would never happen in this land."

The government had argued that the law did not change the practices of the United States since the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks and that the plaintiffs did not have legal standing to sue.

In March, the judge seemed sympathetic to the government's arguments until she asked a government attorney if he could assure the plaintiffs that they would not face detention under the law for their work.

She wrote Wednesday that the failure of the government to make such a representation required her to assume that government takes the position that the law covers "a wide swath of expressive and associational conduct."

Other Sources: Wikipedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Katherin...

Biographical Directory of Federal Judges

Forrest, Katherine Bolan

Born 1964 in New York, NY

Federal Judicial Service:

Judge, U.S. District Court, Southern District of New York

Nominated by Barack Obama on May 4, 2011, to a seat vacated by Jed S. Rakoff. Confirmed by the Senate on October 13, 2011, and received commission on October 17, 2011.

Education:

Wesleyan University, B.A., 1986

New York University School of Law, J.D., 1990

Professional Career:

Private practice, New York City, 1990-2010

Deputy assistant attorney general, U.S. Department of Justice, Washington, D.C., 2010-2011

Biography prior to appointment:

Katherine B. Forrest is a Deputy Assistant Attorney General in the Antitrust Division of the United States Department of Justice in Washington, D.C., a position she has held since October 2010. Prior to joining the Department of Justice, she worked at the law firm of Cravath, Swaine & Moore LLP in New York, handling an array of commercial litigation with a particular focus on antitrust, copyright, and digital media. Forrest worked at Cravath beginning in 1990, becoming a partner at the law firm in 1998. She received her J.D. in 1990 from the New York University School of Law and her B.A., with honors, from Wesleyan University in 1986.

More Essential Than Ever: The Fourth Amendment in the Twenty First Century

More Essential Than Ever: The Fourth Amendment in the Twenty First Century by Stephen J. Schulhofer

by Stephen J. SchulhoferSynopsis

When the states ratified the Bill of Rights in the eighteenth century, the Fourth Amendment seemed straightforward. It requires that government respect the right of citizens to be "secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures." Of course, "papers and effects" are now digital and thus more vulnerable to government spying. But the biggest threat may be our own weakening resolve to preserve our privacy.

In this potent new volume in Oxford's Inalienable Rights series, legal expert Stephen J. Schulhofer argues that the Fourth Amendment remains, as the title says, more essential than ever. From data-mining to airport body scans, drug testing and aggressive police patrolling on the streets, privacy is under assault as never before--and we're simply getting used to it. But the trend is threatening the pillars of democracy itself, Schulhofer maintains. "Government surveillance may not worry the average citizen who reads best-selling books, practices a widely accepted religion, and adheres to middle-of-the-road political views," he writes. But surveillance weighs on minorities, dissenters, and unorthodox thinkers, "chilling their freedom to read what they choose, to say what they think, and to associate with others who are like-minded." All of us are affected, he adds. "When unrestricted search and surveillance powers chill speech and religion, inhibit gossip and dampen creativity, they undermine politics and impoverish social life for everyone." Schulhofer offers a rich account of the history and nuances of Fourth Amendment protections, as he examines such issues as street stops, racial profiling, electronic surveillance, data aggregation, and the demands of national security. The Fourth Amendment, he reminds us, explicitly authorizes invasions of privacy--but it requires justification and accountability, requirements that reconcile public safety with liberty.

Combining a detailed knowledge of specific cases with a deep grasp of Constitutional law, More Essential than Ever offers a sophisticated and thoughtful perspective on this important debate.

This looks interesting.

This looks interesting. American Founding Son: John Bingham and the Invention of the Fourteenth Amendment

by Gerard N Magliocca (no photo)

by Gerard N Magliocca (no photo)Synopsis:

John Bingham was the architect of the rebirth of the United States following the Civil War. A leading antislavery lawyer and congressman from Ohio, Bingham wrote the most important part of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which guarantees fundamental rights and equality to all Americans. He was also at the center of two of the greatest trials in history, giving the closing argument in the military prosecution of John Wilkes Booth's co-conspirators for the assassination of Abraham Lincoln and in the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson. And more than any other man, Bingham played the key role in shaping the Union's policy towards the occupied ex-Confederate States, with consequences that still haunt our politics. American Founding Son provides the most complete portrait yet of this remarkable statesman. Drawing on his personal letters and speeches, the book traces Bingham's life from his humble roots in Pennsylvania through his career as a leader of the Republican Party. Gerard N. Magliocca argues that Bingham and his congressional colleagues transformed the Constitution that the Founding Fathers created, and did so with the same ingenuity that their forbears used to create a more perfect union in the 1780s. In this book, Magliocca restores Bingham to his rightful place as one of our great leaders. Gerard N. Magliocca is the Samuel R. Rosen Professor at Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law. He is the author of three books on constitutional law, and his work on Andrew Jackson was the subject of an hour-long program on C-Span's Book TV.

Just read a review of this in NY Times Book Review, looks apropos for this thread

Just read a review of this in NY Times Book Review, looks apropos for this thread by Thomas Healy (no photo)

by Thomas Healy (no photo)SYNOPSIS

A gripping intellectual history reveals how conservative justice Oliver Wendell Holmes became a free-speech advocate and established the modern understanding of the First AmendmentThe right to express one’s political views seems an indisputable part of American life. After all, the First Amendment proudly proclaims that Congress can make no law abridging the freedom of speech. But well into the twentieth century, that right was still an unfulfilled promise, with Americans regularly imprisoned merely for protesting government policies. Indeed, our current understanding of free speech comes less from the First Amendment itself than from a most unlikely man: the Supreme Court justice Oliver Wendell Holmes. A lifelong conservative, he disdained all individual rights. Yet in 1919, it was Holmes who wrote a court opinion that became a canonical statement for free speech as we know it.

Why did Holmes change his mind? That question has puzzled historians for almost a century. Now, with the aid of newly discovered letters and memos, the law professor Thomas Healy reconstructs in vivid detail Holmes’s journey from free-speech skeptic to First Amendment hero. It is the story of a remarkable behind-the-scenes campaign by a group of progressives to bring a legal icon around to their way of thinking—and a deeply touching human narrative of an old man saved from loneliness and despair by a few unlikely young friends.

Beautifully written and exhaustively researched, The Great Dissent is intellectual history at its best, revealing how free debate can alter the life of a man and the legal landscape of an entire nation.

Yes, thank you Peter. I cited this book on The Metaphysical Club site in the Oliver Wendell Holmes thread.

Hope you join in on the discussion over there too.

by

by

Louis Menand

Louis Menand

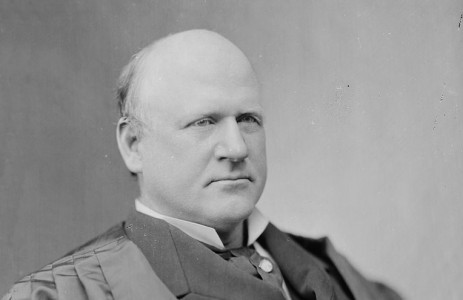

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.

Hope you join in on the discussion over there too.

by

by

Louis Menand

Louis Menand Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.

message 126:

by

Jerome, Assisting Moderator - Upcoming Books and Releases

(new)

An upcoming book:

Release date: May 20, 2014

The Second Amendment: A Biography

by Michael Waldman (no photo)

by Michael Waldman (no photo)

Synopsis:

By the president of the prestigious Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law, the life story of the most controversial, volatile, misunderstood provision of the Bill of Rights.

At a time of renewed debate over guns in America, what does the Second Amendment mean? This book looks at history to provide some surprising, illuminating answers.

The Amendment was written to calm public fear that the new national government would crush the state militias made up of all (white) adult men—who were required to own a gun to serve. Waldman recounts the raucous public debate that has surrounded the amendment from its inception to the present. As the country spread to the Western frontier, violence spread too. But through it all, gun control was abundant. In the 20th century, with Prohibition and gangsterism, the first federal control laws were passed. In all four separate times the Supreme Court ruled against a constitutional right to own a gun.

The present debate picked up in the 1970s—part of a backlash to the liberal 1960s and a resurgence of libertarianism. A newly radicalized NRA entered the campaign to oppose gun control and elevate the status of an obscure constitutional provision. In 2008, in a case that reached the Court after a focused drive by conservative lawyers, the US Supreme Court ruled for the first time that the Constitution protects an individual right to gun ownership. Famous for his theory of “originalism,” Justice Antonin Scalia twisted it in this instance to base his argument on contemporary conditions.

In The Second Amendment: A Biography, Michael Waldman shows that our view of the amendment is set, at each stage, not by a pristine constitutional text, but by the push and pull, the rough and tumble of political advocacy and public agitation.

Release date: May 20, 2014

The Second Amendment: A Biography

by Michael Waldman (no photo)

by Michael Waldman (no photo)Synopsis:

By the president of the prestigious Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law, the life story of the most controversial, volatile, misunderstood provision of the Bill of Rights.

At a time of renewed debate over guns in America, what does the Second Amendment mean? This book looks at history to provide some surprising, illuminating answers.

The Amendment was written to calm public fear that the new national government would crush the state militias made up of all (white) adult men—who were required to own a gun to serve. Waldman recounts the raucous public debate that has surrounded the amendment from its inception to the present. As the country spread to the Western frontier, violence spread too. But through it all, gun control was abundant. In the 20th century, with Prohibition and gangsterism, the first federal control laws were passed. In all four separate times the Supreme Court ruled against a constitutional right to own a gun.

The present debate picked up in the 1970s—part of a backlash to the liberal 1960s and a resurgence of libertarianism. A newly radicalized NRA entered the campaign to oppose gun control and elevate the status of an obscure constitutional provision. In 2008, in a case that reached the Court after a focused drive by conservative lawyers, the US Supreme Court ruled for the first time that the Constitution protects an individual right to gun ownership. Famous for his theory of “originalism,” Justice Antonin Scalia twisted it in this instance to base his argument on contemporary conditions.

In The Second Amendment: A Biography, Michael Waldman shows that our view of the amendment is set, at each stage, not by a pristine constitutional text, but by the push and pull, the rough and tumble of political advocacy and public agitation.

Here's a retired Supreme Court justice,appointed by a Republican President, who really seems to consider cases on the basis of evidence and precedents rather than politics. This book, while we may not agree with everything in it, is definitely worth reading. I especially like his comments on campaign finance (the corporation itself can't vote and therefore shouldn't be allowed to throw money at a candidate) and gun control (it's surprisingly only recently in our country's 200+ years of history that the 2nd amendment has been warped to fit the desires of the NRA) especially appealed to me. Agree or disagree, his history of the precedents on these and four other issues are illuminating.

Here's a retired Supreme Court justice,appointed by a Republican President, who really seems to consider cases on the basis of evidence and precedents rather than politics. This book, while we may not agree with everything in it, is definitely worth reading. I especially like his comments on campaign finance (the corporation itself can't vote and therefore shouldn't be allowed to throw money at a candidate) and gun control (it's surprisingly only recently in our country's 200+ years of history that the 2nd amendment has been warped to fit the desires of the NRA) especially appealed to me. Agree or disagree, his history of the precedents on these and four other issues are illuminating. by

by

John Paul Stevens

John Paul Stevens

message 130:

by

Jerome, Assisting Moderator - Upcoming Books and Releases

(last edited Feb 20, 2019 01:00PM)

(new)

Freedom for the Thought That We Hate: A Biography of the First Amendment

by Anthony Lewis (no photo)

by Anthony Lewis (no photo)

Synopsis:

More than any other people on earth, Americans are free to say and write what they think. The media can air the secrets of the White House, the boardroom, or the bedroom with little fear of punishment or penalty. The reason for this extraordinary freedom is not a superior culture of tolerance, but just fourteen words in our most fundamental legal document: the free expression clauses of the First Amendment to the Constitution. In Lewis’s telling, the story of how the right of free expression evolved along with our nation makes a compelling case for the adaptability of our constitution. Although Americans have gleefully and sometimes outrageously exercised their right to free speech since before the nation’s founding, the Supreme Court did not begin to recognize this right until 1919. Freedom of speech and the press as we know it today is surprisingly recent. Anthony Lewis tells us how these rights were created, revealing a story of hard choices, heroic (and some less heroic) judges, and fascinating and eccentric defendants who forced the legal system to come face-to-face with one of America’s great founding ideas.

by Anthony Lewis (no photo)

by Anthony Lewis (no photo)Synopsis:

More than any other people on earth, Americans are free to say and write what they think. The media can air the secrets of the White House, the boardroom, or the bedroom with little fear of punishment or penalty. The reason for this extraordinary freedom is not a superior culture of tolerance, but just fourteen words in our most fundamental legal document: the free expression clauses of the First Amendment to the Constitution. In Lewis’s telling, the story of how the right of free expression evolved along with our nation makes a compelling case for the adaptability of our constitution. Although Americans have gleefully and sometimes outrageously exercised their right to free speech since before the nation’s founding, the Supreme Court did not begin to recognize this right until 1919. Freedom of speech and the press as we know it today is surprisingly recent. Anthony Lewis tells us how these rights were created, revealing a story of hard choices, heroic (and some less heroic) judges, and fascinating and eccentric defendants who forced the legal system to come face-to-face with one of America’s great founding ideas.

10 huge Supreme Court cases about the 14th Amendment

10 huge Supreme Court cases about the 14th AmendmentJuly 9, 2015 by NCC Staff

John Marshall Harlan

On the 147th anniversary of the 14th Amendment, Constitution Daily looks at 10 historic Supreme Court cases about due process and equal protection under the law.

On July 9, 1868, Louisiana and South Carolina voted to ratify the amendment, after they had rejected it a year earlier. The votes made the 14th Amendment officially part of the Constitution. But in the ensuing years, the Supreme Court was slow to decide how the new (and old) rights guaranteed under the federal constitution applied to the states.

In the early Supreme Court decisions about the 14th Amendment, the Court often ruled in favor of limiting the incorporation of these rights on a state and local level. But starting in the 1920s, the Court embraced the application of due process and equal protection, despite state laws that conflicted with the 14th Amendment.

Here is a look at 10 famous Court decisions that show the progression of the 14th Amendment from Reconstruction to the era of affirmative action.

The Slaughter-House Cases (14 Apr 1873) ―In the Slaughter-House Cases, waste products from slaughterhouses located upstream of New Orleans had caused serious health problems for years by the time Louisiana decided to consolidate the industries into one slaughterhouse located south of the city. Slaughterhouse owners were incensed. They challenged the state’s action citing the 14th Amendment’s Privileges and Immunities Clause as their remedy. The Court said that the Privileges and Immunities Clause only prevented the federal government from abridging privileges and immunities guaranteed in the 14th Amendment and that the clause did not apply to the states. The move gutted the Privilege and Immunities Clause of its effect and kept the door open for Jim Crow laws in the South. To this day the Privileges and Immunities Clause is seldom invoked.

Plessy v. Ferguson (18 May 1896) ―The Louisiana legislature had passed a law requiring black and white residents to ride separate, but equal, train cars. In 1892, Louisiana police arrested Homer Adolph Plessy—who was seven-eighths Caucasian—for taking his seat on a train car reserved for “whites only” because he refused to move to a separate train car reserved for blacks. Plessy argued that the Louisiana statute violated the 13th and 14th Amendments by treating black Americans inferior to whites. Plessy lost in every court in Louisiana before appealing to the Supreme Court in 1896. In a 7-1 decision, the Court held that as long as the facilities were equal, their separation satisfied the 14th Amendment. Justice Harlan authored the lone dissent. Passionately he clarified that the Constitution was color-blind, railing the majority for an opinion which he believed would match Dred Scott in infamy.

Lochner v. New York (17 Apr 1905) ―Lochner, a baker from New York, was convicted of violating the New York Bakeshop Act, which prohibited bakers from working more than 10 hours a day and 60 hours a week. The Supreme Court struck down the Bakeshop Act, however, ruling that it infringed on Lochner’s “right to contract.” The Court extracted this “right” from the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment, a move that many believe exceeded judicial authority.

Gitlow v. New York (08 June 1925) ―Prior to 1925, provisions in the Bill of Rights were not always guaranteed on the local level and usually applied only to the federal government. Gitlow illustrated one of the Court’s earliest attempts at incorporation, that is, the process by which provisions in the Bill of Rights has been applied to the states. A socialist named Benjamin Gitlow printed an article advocating the forceful overthrow of government and was arrested pursuant to New York state law. Gitlow argued that the First Amendment guaranteed freedom of speech and the press. On appeal, the Supreme Court expressed that the First Amendment applied to New York through the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment. However, the Court ultimately ruled that Gitlow’s speech was not protected under the First Amendment by applying the “clear and present danger” test. The Court’s ruling was the first of many instances of incorporating the Bill of Rights.

Brown v. Board of Education (17 May 1954) ―It is impossible to mention victories of the Civil Rights Movement without pointing to Brown v. Board of Education. Following the Court’s ruling in 1896 of Plessy v. Ferguson, segregation of public schools based solely on race was allowed by states if the facilities were “equal.” Brown overturned that decision. Regardless of the “equality” of facilities, the Court ruled that separate is inherently unequal. Thus public school segregation based on race was found in violation of the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause.

Mapp v. Ohio (19 Jun 1961) ―What happens when the police obtain evidence from an illegal search or seizure? Before the Court’s decision in Mapp, the evidence could still be collected, but the police would be censured. Police had received a tip that a bombing suspect might be located at Dollree Mapp’s home in suburban Cleveland, Ohio. When police asked to search her home, Mapp refused unless the police produced a warrant. The police used a piece of paper as a fake warrant and gained access to her home illegally. After searching the house without finding the bombing suspect, police discovered sexually explicit materials and arrested Mapp pursuant to state law that prohibited the possession of obscene materials. Mapp was convicted of possessing obscene materials and faced up to seven years in prison before she appealed her case on the argument that she had a First Amendment right to possess the material. The Court held that evidence collected from an unlawful search—as this search obviously had been—from be excluded from trial. Justice Clark’s majority opinion incorporated the Fourth Amendment’s protection of privacy using the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment, a very controversial move.

Gideon v. Wainwright (18 Mar 1963) ― Prior to 1962, indigent Americans were not always guaranteed access to legal counsel despite the Sixth Amendment. Gideon, a Florida resident, was charged in Florida state court for breaking and entering into a poolroom with the intent to commit a crime. Due to his poverty, Gideon asked the Florida court to appoint an attorney for him. The court declined to do this and pointed to state law which said that the only time indigent defendants could be appointed an attorney was when charged with a capital offense. Left with no other choice, Gideon represented himself in trial and lost. He filed a petition of habeas corpus to the Florida Supreme Court, arguing that he had a constitutional right to be represented with an attorney, but the Florida Supreme Court did not grant him any relief. A unanimous United States Supreme Court said that state courts are required under the 14th Amendment to provide counsel in criminal cases to represent defendants who are unable to afford to pay their own attorneys, guaranteeing the Sixth Amendment’s similar federal guarantees.

Griswold v. Connecticut (07 Jun 1965) ―You know when you’re walking down the street at night with lights in front of you and behind you, and you get that really dark shadow? In the scientific community, that shadow is known as an “umbra.” Flanking that dark shadow on the ground are two or more, half-shadows, not quite as dark, but darker than the well-lit sidewalk around you. Those shadows are known as “penumbras” and were used to explain the most controversial issue of arguably the most controversial Supreme Court case in the 20th century. Estelle Griswold was the director of a Planned Parenthood clinic in Connecticut when she was arrested for violating a state statute that prohibited counseling and prescription of birth control to married couples. The question before the Supreme Court was whether the Constitution protected the right of married couples to privately engage in counseling regarding contraceptive use and procurement. Justice Douglas articulated that although not explicit, the penumbras of the Bill of Rights contained a fundamental “right to privacy” that was protected by the 14th Amendment’s Due Process Clause. Griswold’s “right to privacy” has been applied to many other controversial decisions such as Eisenstadt and Roe v. Wade. It remains at the core of substantive due process debate today.

Loving v. Virginia (12 Jun 1967) ―By 1967, 16 states had still not repealed their anti-misogyny laws that forbid interracial marriages. Mildred and Richard Loving were residents of one such state, Virginia, who had fallen in love and wanted to get married. Under Virginia’s laws, however, Richard, a white man, could not marry Mildred, a woman of African-American and Native American descent. The two travelled to Washington D.C. where they could be married, but they were arrested state law which prohibited inter-racial marriage. Because their offense was a criminal conviction, after being found guilty, they were given a prison sentence of one year. The trial judge suspended the sentence for 25 years on the condition that the couple leave Virginia. On Appeal, the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia ruled that the state had an interest in preserving the “racial integrity” of its constituents and that because the punishment applied equally to both races, the statute did not violate the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. The United States Supreme Court in a unanimous decision reversed the Virginia Court’s ruling and held that the Equal Protection Clause required strict scrutiny to apply to all race based classifications. Furthermore, the Court concluded that the law was rooted in invidious racial discrimination, making it impossible to satisfy a compelling government interest. The Loving decision still stands as a milestone in the Civil Rights Movement.

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (26 Jun 1978)— Allan Bakke, a white man, had been denied access to the University of California Medical School at Davis on two separate occasions. The medical school set aside 16 spots for minority candidates in an attempt to address unfair minority exclusion from medical school. All 16 candidates from both years had test scores lower than Bakke’s but gained admission. Bakke contested that his exclusion from the Medical School was entirely the result of his race. The Supreme Court ruled in a severely fractured plurality that the university’s use of strict racial quotas was unconstitutional and ordered that the medical school admit Bakke, but it also said that race could be used as one of several factors in the admissions process. Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr., cast the deciding vote ordering the medical school to admit Bakke. However, in his opinion, Powell said that the rigid use of racial quotas violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment.

In addition to these 10 famous cases, this June’s decision in Obergefell v. Hodges, which recognized a national right to same-sex marriage, will likely join the list of notable 14th Amendment cases. In the Court’s 5-4 decision, Justice Anthony Kennedy held that “the Fourteenth Amendment requires a State to license a marriage between two people of the same sex and to recognize a marriage between two people of the same sex when their marriage was lawfully licensed and performed out-of-State.”

(Source: National Constitution Center)

Though it was already a buddy read here, Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition by Daniel Okrent not only covers the 18th Amendment that created Prohibition and the 21st, which repealed it, but the 16th Amendment (income tax), which made Prohibition financially feasible, and the 19th, which gave women the vote. Women were the original temperance activists.

Though it was already a buddy read here, Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition by Daniel Okrent not only covers the 18th Amendment that created Prohibition and the 21st, which repealed it, but the 16th Amendment (income tax), which made Prohibition financially feasible, and the 19th, which gave women the vote. Women were the original temperance activists. by

by

Daniel Okrent

Daniel Okrent

Thanks for posting, Kressel! That was a great book and I encourage anyone that has not read it and plans to, to join in the Buddy Read discussion at any time. Here's the link to the folder:

Thanks for posting, Kressel! That was a great book and I encourage anyone that has not read it and plans to, to join in the Buddy Read discussion at any time. Here's the link to the folder:Last Call Buddy Read

by

by

Daniel Okrent

Daniel Okrent

It appears that the 14 Amendment is coming under fire again regarding the children born in the USA of illegal aliens. The amendment was originally added to the Constitution to cover the rights of recently freed slaves but now is being debated as to whether it applies to the current immigration situation. In my opinion, it is quite clear that is protects all individuals born in the United States but some are questioning the intent which was particularly directed at freed slaves, ensuring that they were considered citizens and does not apply to illegal immigrants' children. Below is a short summary of the amendment.

It appears that the 14 Amendment is coming under fire again regarding the children born in the USA of illegal aliens. The amendment was originally added to the Constitution to cover the rights of recently freed slaves but now is being debated as to whether it applies to the current immigration situation. In my opinion, it is quite clear that is protects all individuals born in the United States but some are questioning the intent which was particularly directed at freed slaves, ensuring that they were considered citizens and does not apply to illegal immigrants' children. Below is a short summary of the amendment."The 14th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified on July 9, 1868, and granted citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States,” which included former slaves recently freed. In addition, it forbids states from denying any person "life, liberty or property, without due process of law" or to "deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” By directly mentioning the role of the states, the 14th Amendment greatly expanded the protection of civil rights to all Americans and is cited in more litigation than any other amendment."

(Source: Library of Congress)

Yes - Mr. Trump et al. I think that there is a point to be made about the original intent of the 14th amendment versus how it is being manipulated in part today. I do not think it should apply to illegal immigrants who come to America illegally and have a baby here so that they can avoid deportation or create sympathy for the baby. I have great sympathy for all of the immigrants, their offspring, newborns and my ancestors were immigrants themselves but came in the legal way and probably also did not have the best of circumstances on Ellis Island or however they came but yet followed the laws that we already have. It makes it tough to control terrorism within our country if we cannot control illegal immigrants crossing at our borders without our being able to protect them. It is a catch 22. I doubt any country in the world has as many problems with their borders as we have with Mexico. And Mexico doesn't seem to be doing much about the situation. I am willing to listen to any of my Mexican friends who are group members regarding their perspective on this situation which is draining our economy, our public schools, and our health and welfare systems unfairly I believe and affecting the treatment and resources for our own naturalized citizens who may be having a difficult time themselves. Hard to find a balance when the borders are obviously not secure and this seems to be the modus operandi being used and the misuse of the 14th amendment. Interested to hear other points of view since this is now becoming a burning topic as it should be.

Well Bentley I am reading the whole Constitution right now ironically. If a child is born in this country according to the 14th Amendment that child is a US citizen. The parents are a different matter. You can deport the parents being illegal but the child you cannot according to the amendment. You would be deporting a US citizen.

Well Bentley I am reading the whole Constitution right now ironically. If a child is born in this country according to the 14th Amendment that child is a US citizen. The parents are a different matter. You can deport the parents being illegal but the child you cannot according to the amendment. You would be deporting a US citizen.

I would agree basically with your thoughts but at this point I think the 14th amendment does protect those children. Legislative intent, unfortunately, does not translate well into the legalese of the law. The issue is that we have lost control of the border and therein lies the problem. I don't see that amendment being modified.......we should be looking at how to avoid the influx of illegals. Somehow the building of a wall around our country seems ludicrous but what is the answer?

I would agree basically with your thoughts but at this point I think the 14th amendment does protect those children. Legislative intent, unfortunately, does not translate well into the legalese of the law. The issue is that we have lost control of the border and therein lies the problem. I don't see that amendment being modified.......we should be looking at how to avoid the influx of illegals. Somehow the building of a wall around our country seems ludicrous but what is the answer?

This issue being brought up is yet another reason why we should all read the Constitution in it's entirety.

This issue being brought up is yet another reason why we should all read the Constitution in it's entirety.

You are right, Doreen. I bought a little paperback copy of the Constitution and read it last year. Our country's founders could not have known some of the issues that would face us in the future, so it boils down to the interpretation of the language and not the original intent.

You are right, Doreen. I bought a little paperback copy of the Constitution and read it last year. Our country's founders could not have known some of the issues that would face us in the future, so it boils down to the interpretation of the language and not the original intent.

Sort of my point Jill. If you repeal the 14th Amendment you would have to deport numerous US citizens. My grandparents on my father's side never became citizens so if the 14th Amendment were repealed would that mean I'd have to leave too? This amendment has never been an issue until Ferret Head brought it up in reference to Mexico only.

Sort of my point Jill. If you repeal the 14th Amendment you would have to deport numerous US citizens. My grandparents on my father's side never became citizens so if the 14th Amendment were repealed would that mean I'd have to leave too? This amendment has never been an issue until Ferret Head brought it up in reference to Mexico only.

Doreen wrote: "Well Bentley I am reading the whole Constitution right now ironically. If a child is born in this country according to the 14th Amendment that child is a US citizen. The parents are a different mat..."

I think Doreen it boils down to interpretation which was not the intent of the 14th amendment which is being misused and abused at this point. I disagree with this birthright being given to children of illegal immigrants who came to this country illegally - plain and simple. I have read the constitution in its entirety many many times and I still believe that we are being used and abused by illegal immigrants who are coming to this country and breaking our laws and worse and we are all paying for it with an economy which frankly cannot afford to pay for Mexico. Mexico has to do something about this frankly as well. I am sorry you disagree with the interpretation and I have the greatest sympathy and empathy for babies, and legal immigrants but this should be changed and the loophole removed. I think it would stop a great many of these immigrants thinking they can thumb their noses at our laws. Our ancestors were not allowed to flaunt our laws and ended up on Ellis Island legally - and did not do this - why should we allow this now and then complain that our borders are not stopping terrorism. If we cannot even control our borders - how do you expect homeland security to safeguard our citizens.

I think Doreen it boils down to interpretation which was not the intent of the 14th amendment which is being misused and abused at this point. I disagree with this birthright being given to children of illegal immigrants who came to this country illegally - plain and simple. I have read the constitution in its entirety many many times and I still believe that we are being used and abused by illegal immigrants who are coming to this country and breaking our laws and worse and we are all paying for it with an economy which frankly cannot afford to pay for Mexico. Mexico has to do something about this frankly as well. I am sorry you disagree with the interpretation and I have the greatest sympathy and empathy for babies, and legal immigrants but this should be changed and the loophole removed. I think it would stop a great many of these immigrants thinking they can thumb their noses at our laws. Our ancestors were not allowed to flaunt our laws and ended up on Ellis Island legally - and did not do this - why should we allow this now and then complain that our borders are not stopping terrorism. If we cannot even control our borders - how do you expect homeland security to safeguard our citizens.

Doreen wrote: "This issue being brought up is yet another reason why we should all read the Constitution in it's entirety."