Classics and the Western Canon discussion

Divine Comedy, Dante

>

Paradiso 1: Ascent from the Earthly Paradise to Heaven

Agree entirely with your assessment, Laurel. I closed the day yesterday reading through the Canto and Ciardi's comments, and said, those feel mostly like words following each other, not like ideas or thoughts I can grasp. I tried again this morning, and there may be hope. But what a contrast with reading

11/22/63

, which is my other "required" reading for the days immediately ahead. Maybe the juxtaposition is sanity inducing.

Agree entirely with your assessment, Laurel. I closed the day yesterday reading through the Canto and Ciardi's comments, and said, those feel mostly like words following each other, not like ideas or thoughts I can grasp. I tried again this morning, and there may be hope. But what a contrast with reading

11/22/63

, which is my other "required" reading for the days immediately ahead. Maybe the juxtaposition is sanity inducing.On about the fourth read (for me), lines 1-12 have become a powerful statement of awe -- and, oh, how different than the despondent mood that opened The Inferno.

I can't (or won't) read everything that repeatedly, but the next thing that I noticed was the turn from the monotheistic to the pagan and evoking the support of Apollo. I took the time to learn of the two peaks of Parnassus (Nisa and Cyrrha) -- the first associated with the Muses, the second with Apollo -- but what are the chances I shall remember this? And what an image of the emptying out writing such as this demanded of Dante is given by the tale of Marsyas -- lines 19-24 circle back and repeat like a refrain the sentiment of lines 4-12. This seems harder than childbirth, the analogy perhaps more oft used in describing the difficulties of delivering human-made creation.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mount_Pa...

http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-ent...

http://ancienthistory.about.com/od/my...

There are slight differences among these accounts of Marsyas. Ciardi's note is also of interest here: "Note that in this godly sport the skin was not pulled off Marsyas but that Marsyas was pulled out of his skin. In citing this incident Dante may be praying that he himself, in a sense, be pulled out of himself (i.e., be made to outdo himself), however painfully."

(Totally irrelevant to Paradiso, but the video here is a bit of a virtual sidetrip to an intersection of mythology and skiing: http://www.mlahanas.de/Greece/Regions.... Ah, to be young again.)

http://donbarone.selfip.net/Poussin%2...

http://donbarone.selfip.net/Poussin%2...This page has some images by Poussin related to Apollo and Daphne, including some excerpts from Ovid of the formation of the laurel tree from their thwarted love, which Dante refers to here in lines 25ff of this Canto.

Perhaps my favorite images of the transformation of Daphne into the laurel tree were some Bernini sculpture displays (his clay models) at Harvard a number of years ago -- one "watched" the nymph morphed into her tree. I had never thought before this moment of some of the possible parallels between the love of Daphne and Apollo and that of Beatrice and Dante. Even after divine revelation alongside his beloved (but denied) Beatrice, Dante somehow cannot flee from his desired pride as he seeks the crown of "a poet's triumph". Line 29.

I'm still catching up with Purgatory, as I suspect others are, but I'm determined to keep up with Paradise!

I'm still catching up with Purgatory, as I suspect others are, but I'm determined to keep up with Paradise!Only one read through so far, but I echo the Wow, and that this will take more than one day to absorb.

I don't know whether it's Dante or the translator (Musa for my first read through) or both, but the language here seems much more exalted and -- well, Heavenly -- than in the earlier sections.

There's a lot in this Canto that I don't get yet, including this deal with the three circles and the four crosses -- I just can't visualize the situation as either Musa or Hollander describe it. Does anybody else think they have a handle on what's going on there?

I'm thinking still about his invoking Apollo here. I thought that part of why he invoked the classical muses in the earlier sections was because he had Virgil, the classical author, as his guide. But here we're now in the pure realm of the Christian God, yet he's still back asking for the help of the pagan gods. I find that curious.

I'm not sure what he means, in lines 103-5,

All things created have an order

in themselves, and this begets the form

that lets the universe resemble God.

How does the universe resemble God? Should we know now, or is this something we're going to learn as we move up in (toward?) Paradise?

But I do love the image of Beatrice sighing at the ignorance of Dante [100-102]:

Then she, having sighed with pity,

bent her eyes on me with just that look

a mother casts on her delirious child,

Although given the way he wrote about Beatrice while she was still alive, I don't think it's as a mother figure that he normally thought of her, unless we're to add the Oedipus complex into Christian theology!

And all this is just the beginning!

Lily wrote: ... including some excerpts from Ovid of the formation of the laurel tree from their thwarted love, which Dante refers to here in lines 25ff of this Canto...."

Lily wrote: ... including some excerpts from Ovid of the formation of the laurel tree from their thwarted love, which Dante refers to here in lines 25ff of this Canto...."I was surprised by Musa's translation of line 25

"and you shall see me as your chosen tree,"

since his chosen tree was the woman he loved, so that if anything it should have been Dante calling Beatrice his laurel tree since he had lost her, not to transformation but to death.

But the Princeton Dante project translation (which seems to be the Hollander) has it somewhat differently:

"you shall find me at the foot of your belovèd tree,"

which makes a lot more sense to me.

Anybody have other translations of line 25 to offer to see what Dante might really have meant?

Everyman wrote: "I'm still catching up with Purgatory, as I suspect others are, but I'm determined to keep up with Paradise!..."

Everyman wrote: "I'm still catching up with Purgatory, as I suspect others are, but I'm determined to keep up with Paradise!..."Those are my sentiments exactly! Now let's see if I can be consistent in acting on them!

Everyman wrote: "I was surprised by Musa's translation of line 25:

Everyman wrote: "I was surprised by Musa's translation of line 25:'and you shall see me as your chosen tree,'....

...Princeton Dante project translation (which seems to be the Hollander) has it somewhat differently:

'you shall find me at the foot of your belovèd tree,' ..."

Ciardi translates:

"and you shall see me come to your dear grove (25)

to crown myself with those green leaves which you

and my high theme shall make me worthy of."

Longfellow did this:

"Thou'lt see me come unto thy darling tree (25)

And crown myself thereafter with those leaves

Of which the theme and thou shall make me worthy."

A bit more on Apollo and Daphne: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apollo_a...

A bit more on Apollo and Daphne: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apollo_a...http://smarthistory.khanacademy.org/b...

The second link has a lovely video and telling of the story. (Bernini executed this sculpture ~1622-25, some 300 years after Dante spun his tale.)

Everyman wrote: "Lily wrote: ... including some excerpts from Ovid of the formation of the laurel tree from their thwarted love, which Dante refers to here in lines 25ff of this Canto...."

Everyman wrote: "Lily wrote: ... including some excerpts from Ovid of the formation of the laurel tree from their thwarted love, which Dante refers to here in lines 25ff of this Canto...."I was surprised by Musa'..."

The poet is addressing Apollo here. The laurel is Apollo's chosen tree (mine, too.)

Lily wrote: "http://donbarone.selfip.net/Poussin%2...

Lily wrote: "http://donbarone.selfip.net/Poussin%2...This page has some images by Poussin related to Apollo and Daphne, including some excerpts from Ovid of the formation of the laurel tree from their..."

Great sleuthing, Lily!

Lily wrote: "A bit more on Apollo and Daphne:..."

Lily wrote: "A bit more on Apollo and Daphne:..."We really need to do Ovid here before too much longer. It suffuses so much other literature!

Everyman wrote: "There's a lot in this Canto that I don't get yet, including this deal with the three circles and the four crosses -- I just can't visualize the situation as either Musa or Hollander describe it. Does anybody else think they have a handle on what's going on there? "

Everyman wrote: "There's a lot in this Canto that I don't get yet, including this deal with the three circles and the four crosses -- I just can't visualize the situation as either Musa or Hollander describe it. Does anybody else think they have a handle on what's going on there? "There is a diagram in Singleton's commentary which is helpful. It shows the four circles -- the equator, the ecliptic, the equinoctial colure, and the horizon -- and the day on which they meet at one point is the vernal equinox. This diagram is similar :

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Col...

I've read through the canto twice and even the commentary is a bit baffling, but I'll keep trying. So far it seems that a lot of the astronomical imagery and mythological allusions are tied to the Sun, the "lamp of the world." Dante is racing through and to the divine light but doesn't understand it yet. Maybe we will catch up as he does.

More than once in this canto Dante refers back to the experience the apostle Paul had of being caught up into heaven:

More than once in this canto Dante refers back to the experience the apostle Paul had of being caught up into heaven:2 Corinthians 12:2-4

I knew a man in Christ above fourteen years ago, (whether in the body, I cannot tell; or whether out of the body, I cannot tell:God knoweth;) such an one caught up to the third heaven. And I knew such a man, (whether in the body, or out of the body, I cannot tell:God knoweth;) How that he was caught up into paradise, and heard unspeakable words, which it is not lawful for a man to utter.

I think the lack of definiteness that makes canto 1 a bit difficult to follow is an intentional reflection on the unknowableness and inexpressibility of it all.

Dante's references:

Within the heav'n which most receives His light

Was I, and saw such things as man nor knows

Nor skills to tell, returning from that height;

-- 1.4-6, Sayers/Reynolds

If I was naught, O Love that rul'st the height,

Save that of me which Thou didst last create [the soul]

Thou know'st, that didst uplift me by Thy light,

-- 1.73-75, Sayers/Reynolds

(In 1.73-75, he is saying that he did not know whether he was in the body or out of the body when he had this experience.)

Everyman wrote: "Lily wrote: "A bit more on Apollo and Daphne:..."

Everyman wrote: "Lily wrote: "A bit more on Apollo and Daphne:..."We really need to do Ovid here before too much longer. It suffuses so much other literature!"

I was having the same thoughts; thinking even that I needed to tackle it whether or not it became a selection.

Laurele wrote: "Lily wrote: "http://donbarone.selfip.net/Poussin%2...

Laurele wrote: "Lily wrote: "http://donbarone.selfip.net/Poussin%2...This page has some images by Poussin related to Apollo and Daphne, including some excerpts from Ovid..."

Thanks, Laurele. Do check out the video in Msg. 8. It is the closest I can recreate online the wonder I experienced so many years ago at the Fogg Museum. Bernini did such an incredible job of capturing the metamorphosis of Daphne -- including the emotional reactions on the faces of both Apollo and Daphne, but also the splaying of her arms and hands into branches and the morphing of her body into trunk and roots. Then, we know all the subsequent uses of the laurel leaf to create crowns of honor.

(Were both saved from violence in some symbolic ways at least? Or was the self-rendered immolation more sad?)

For illustrations for Paradiso, let us start with this manuscript initial:

For illustrations for Paradiso, let us start with this manuscript initial:http://www.worldofdante.org/media/ima...

Priamo della Quercia: Historiated initial for Paradiso 1. Yates Thompson 36. Illuminated manuscript. British Museum. ~1450.

Imagine being the monk creating this! Straight out of Eco's The Name of the Rose ? (Given what I have been able to trace, Quericia may not have been a monk.)

Everyman wrote: "All things created have an order

Everyman wrote: "All things created have an orderin themselves, and this begets the form

that lets the universe resemble God.

How does the universe resemble God? Should we know now, or is this something we're going to learn as we move up in (toward?) Paradise.."

Just a few things about medieval cosmology that might help here.

In the Ptolemaic/Aristotelian system, the earth is at the center of the universe. Earth is the first and heaviest element, so it is the first substance. Water is next heaviest, so it settles on top of the land. Air is next, and forms a sphere around the earth. Fire is the lightest, and forms a sphere above and around the sphere of air.

Elements were thought to have affinities, and this explained why earthy substances drop to the ground. A stone is "attracted" to the earth, so it falls to the ground. A flame is attracted to the sphere of fire, so it rises toward that sphere. (This is in part what Beatrice is speaking about at lines 109 et seq. ..."in the order whereof I speak all natures are inclined by different lots, nearer and less near unto their principle...")

Above the spheres of earth, water, air and fire, are the heavenly spheres. Each astronomical body had its own sphere which accounted for its movement -- the Moon, Mercury, Venus, Sun, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and finally, the fixed stars. Outside this final sphere was the Prime Mover, who does not move but imparts motion to the universe.

Just as the primary elements of substance have their affinities, so does the human soul. Just as a stone naturally falls to the ground, so too the soul ascends to the divine, because that is how it has been formed by God. That is natural law. “You should not wonder more at your rising, if I deem aright, than at a stream that falls from a mountain top to the base.”

The way I read it, the natural order of the universe operates according to the divine plan. If all of God's creatures follow their natural inclination, the universe works the way it was intended. So far we have seen (in Inferno) what happens when men thwart natural law, and how God allows for forgiveness (in Purgatorio.) Now we will get to see how man ascends to the divine, according to the Divine plan. This should be interesting!

Thomas wrote: "There is a diagram in Singleton's commentary which is helpful. It shows the four circles -- the equator, the ecliptic, the equinoctial colure, and the horizon -- and the day on which they meet at one point is the vernal equinox. This diagram is similar :

Thomas wrote: "There is a diagram in Singleton's commentary which is helpful. It shows the four circles -- the equator, the ecliptic, the equinoctial colure, and the horizon -- and the day on which they meet at one point is the vernal equinox. This diagram is similar :http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Col..."

I get the four circles. But I don't see where he gets three crosses.

Thomas wrote: "Just a few things about medieval cosmology that might help here.

Thomas wrote: "Just a few things about medieval cosmology that might help here."

That's a great summary, and covers nicely the

"All things created have an order

in themselves, .

But it still doesn't answer for me how

"this begets the form

that lets the universe resemble God."

How does the universe resemble God?

Everyman wrote: "Thomas wrote: "There is a diagram in Singleton's commentary which is helpful. It shows the four circles -- the equator, the ecliptic, the equinoctial colure, and the horizon -- and the day on which..."

Everyman wrote: "Thomas wrote: "There is a diagram in Singleton's commentary which is helpful. It shows the four circles -- the equator, the ecliptic, the equinoctial colure, and the horizon -- and the day on which..."The circles cross each other, forming crosses.

Everyman wrote: "Thomas wrote: "Just a few things about medieval cosmology that might help here.

Everyman wrote: "Thomas wrote: "Just a few things about medieval cosmology that might help here."

That's a great summary, and covers nicely the

"All things created have an order

in themselves, .

But it still ..."

I think it is in orderliness that they resemble God.

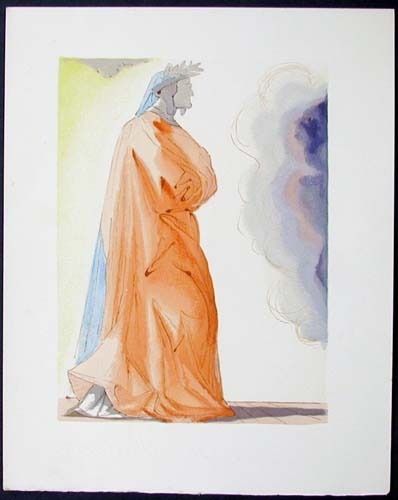

There seem to be no Doré or Blake illustrations for Canto 1. Here is the Dali visual:

There seem to be no Doré or Blake illustrations for Canto 1. Here is the Dali visual:http://www.lockportstreetgallery.com/...

Salvador Dali: Paradiso Canto 1. “Dante.”

Great fire leaps from the smallest spark.

Great fire leaps from the smallest spark.Perhaps, in my wake, prayer will be shaped

With better words that Cyrrha may respond.

--1.34-36, Hollander

Has Dante learned humility?

(I haven't been able to discover who Cyrrha is.)

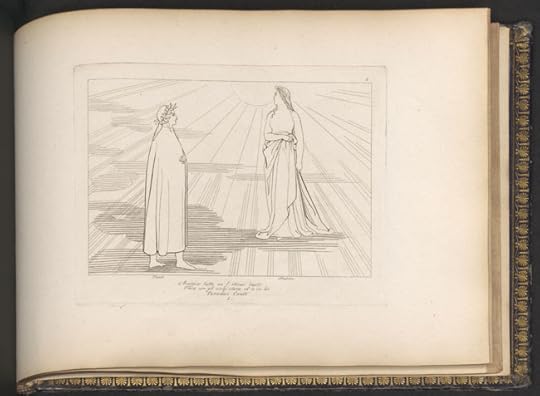

Here is Flaxman (I haven't worked the Botticelli visuals yet):

Here is Flaxman (I haven't worked the Botticelli visuals yet):http://www.worldofdante.org/media/ima...

John Flaxman: Paradiso Canto I. 1/64.“Beatrice Gazes on Eternal Wheeling of Heavens” 1793. Engraving.

Simplistically lovely, but certainly not a particularly imaginative conception of Dante's cosmology.

For Paradiso Canto I images from the Bodleian Library 14th century manuscript try these:

For Paradiso Canto I images from the Bodleian Library 14th century manuscript try these:http://www.bodley.ox.ac.uk/dept/scwms...

Paradiso, Canto I. "Dante and Beatrice Ascend Towards the Sun."

http://www.bodley.ox.ac.uk/dept/scwms...

Paradiso, Canto I. "Beatrice Leading Dante."

"Giorgio Vasari, our most important early source on Botticelli, wrote in 1550 that 'Since Botticelli was a learned man, he wrote a commentary on part of Dante's poem, and after illustrating the Inferno, he printed the work.' Vasari refers Botticelli's drawings for some of the engravings by Baccio Baldini that adorned the first edition of the Divine Comedy published in Florence, in 1481, with commentary by Cristoforo Landino. Botticelli also painted a portrait of the poet, probably to adorn the library of a scholar. These two projects reflect the revival of interest in Dante in late fifteenth-century Florence." -- Jonathan K. Nelson, Syracuse University in Florence.

"Giorgio Vasari, our most important early source on Botticelli, wrote in 1550 that 'Since Botticelli was a learned man, he wrote a commentary on part of Dante's poem, and after illustrating the Inferno, he printed the work.' Vasari refers Botticelli's drawings for some of the engravings by Baccio Baldini that adorned the first edition of the Divine Comedy published in Florence, in 1481, with commentary by Cristoforo Landino. Botticelli also painted a portrait of the poet, probably to adorn the library of a scholar. These two projects reflect the revival of interest in Dante in late fifteenth-century Florence." -- Jonathan K. Nelson, Syracuse University in Florence.(I've not seen examples of the Baccio Baldini engravings. They may be embedded in some of the resource material I haven't plumbed.)

"An anonymous author, writing in about 1540, informs us that Botticelli 'painted and illustrated a Dante on sheepskin for Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici [who also owned the Primavera] which was held to be something marvelous.' He refers to an extraordinarily ambitious and original project. Whereas previous artists had decorated manuscripts of the Divine Comedy, usually with small images of a few key scenes that appeared on the same page as the text, Botticelli planned to illustrate every canto. Moreover, the drawings are very large, arranged horizontally (unlike most books) and full the entire smooth (flesh) side of the parchment. Originally, the images could be seen together with the text, written by Niccolò Mangona on the opposite (rough) side of the parchment. Of this project 92 parchment sheets survive, divided between Berlin and the Vatican. Botticelli completed the outline drawings for nearly all the cantos, but only added colors for a few. The artist shows his 'learning' and artistic skill by representing each of the three realms each in a distinctive way. More than his contemporaries, Botticelli was extremely faithful to Dante's text. Moreover, especially in the teaming, bewildering images of the Inferno, he included a large number of scenes for each canto. For the Purgatorio, Botticelli was somewhat more selective and made greater use of 'rational' perspective: for the Paradiso, his simplified drawings capture the ethereal nature of the text. Botticelli also created a highly detailed cross section map of the underworld, and a frightening portrayal of Satan on a double sheet."

"An anonymous author, writing in about 1540, informs us that Botticelli 'painted and illustrated a Dante on sheepskin for Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici [who also owned the Primavera] which was held to be something marvelous.' He refers to an extraordinarily ambitious and original project. Whereas previous artists had decorated manuscripts of the Divine Comedy, usually with small images of a few key scenes that appeared on the same page as the text, Botticelli planned to illustrate every canto. Moreover, the drawings are very large, arranged horizontally (unlike most books) and full the entire smooth (flesh) side of the parchment. Originally, the images could be seen together with the text, written by Niccolò Mangona on the opposite (rough) side of the parchment. Of this project 92 parchment sheets survive, divided between Berlin and the Vatican. Botticelli completed the outline drawings for nearly all the cantos, but only added colors for a few. The artist shows his 'learning' and artistic skill by representing each of the three realms each in a distinctive way. More than his contemporaries, Botticelli was extremely faithful to Dante's text. Moreover, especially in the teaming, bewildering images of the Inferno, he included a large number of scenes for each canto. For the Purgatorio, Botticelli was somewhat more selective and made greater use of 'rational' perspective: for the Paradiso, his simplified drawings capture the ethereal nature of the text. Botticelli also created a highly detailed cross section map of the underworld, and a frightening portrayal of Satan on a double sheet." -- Jonathan K. Nelson, Syracuse University in Florence. [Bold added.]

No illustration from Botticelli was explicitly associated with Paradiso Canto I.

In case you would like to contrast the drawings for Commedia with his signature works, here are links to some other (very) famous Botticelli pieces:

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia...

"Life of Moses." Vatican. (Uses the technique of multiple vignettes in a single drawing that we have been observing.)

http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-anylOXVETV4...

"Primavera."

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia...

"Birth of Venus."

These all seem to be about 150+ years after Dante wrote his poem.

Everyman wrote: "I get the four circles. But I don't see where he gets three crosses.

Everyman wrote: "I get the four circles. But I don't see where he gets three crosses. ."

Each of the three circles form a cross with the horizon. So four circles, but only three crosses.

Laurele wrote: "I think it is in orderliness that they resemble God.

Laurele wrote: "I think it is in orderliness that they resemble God. ."

I agree. The key word here is "form," which I think has Platonic overtones. Beatrice repeats the word a few lines later, when she speaks about the "intention of the art." God is the Supreme Artist in Dante's conception, and the world resembles Him insofar as it mirrors his intention. That's the best I can come up with.

Laurele wrote: "Great fire leaps from the smallest spark.

Perhaps, in my wake, prayer will be shaped

With better words that Cyrrha may respond.

--1.34-36, Hollander

(Cyrrha?.."

Ah, Lily answered that for us in Post 2. "One of the twin peaks of Parnassus, the mountain sacred to Apollo."

It's so easy to occasionally miss some little details. I happen to remember Lily's answer because I hadn't known who Cyrrha was either.

Perhaps, in my wake, prayer will be shaped

With better words that Cyrrha may respond.

--1.34-36, Hollander

(Cyrrha?.."

Ah, Lily answered that for us in Post 2. "One of the twin peaks of Parnassus, the mountain sacred to Apollo."

It's so easy to occasionally miss some little details. I happen to remember Lily's answer because I hadn't known who Cyrrha was either.

Wishing you all well in your ascent into Paradise. Noted Lily's other reading in @2, Stephen King's 11/22/63. While not generally a Stephen King fan, I devoured this 900 page tome. Believe it or not, Lily, I think you will find some thematic resonance with Divine Comedy--especially in the conclusion.

Yes -- the Muses alone (Nisa) weren't going to be sufficient to help Dante express in words (to mere mortals) what he had experienced; he was turning instead to the god himself, Apollo (Cyrrha). All of which continues to cause me to wonder about the intersection of monotheism and paganism among the learned by 1300. Somehow, I can't imagine Luther or Hull or Calvin (or Barth or Kierkegaard) asking Apollo for help to describe God and heaven. (But I'm enjoying the images of Dante doing so. And some one of you might well produce a quotation suggesting one or more of the learned men I name -- or others like them -- were not immune to evoking pagan powers.)

Yes -- the Muses alone (Nisa) weren't going to be sufficient to help Dante express in words (to mere mortals) what he had experienced; he was turning instead to the god himself, Apollo (Cyrrha). All of which continues to cause me to wonder about the intersection of monotheism and paganism among the learned by 1300. Somehow, I can't imagine Luther or Hull or Calvin (or Barth or Kierkegaard) asking Apollo for help to describe God and heaven. (But I'm enjoying the images of Dante doing so. And some one of you might well produce a quotation suggesting one or more of the learned men I name -- or others like them -- were not immune to evoking pagan powers.)Eman comments on entreating Apollo, too, in Msg. 4.

Incidentally, I did not yet find which peaks of Parnassus have the names of Cyrrha and Nisa, or even if they still do. I wonder if modern day skiers there know.

http://ancienthistory.about.com/cs/gr...

Above is a nice (if not necessarily academically scholarly) source on Apollo and the mythological evolution of his association with the sun. Given that I have lived in an era of electricity and oil, I find it almost impossible to imagine the role the sun must have once played in daily lives. Does Dante link the images of God and sun even more than the Bible itself does?

@Msg 20. Everyman wrote: "...How does the universe resemble God? ..."

@Msg 20. Everyman wrote: "...How does the universe resemble God? ..."These are certainly not exactly the images Dante had in mind in linking God and universe -- his seemed to be more the celestial ones. But I received an email yesterday based on some of the photography at this link and thought of your question. Somehow, for me, the awe of such views can evoke a sense of divine majesty. (Note especially the world going to sleep and the world waking up, then all in between.)

http://drshnsblog.blogspot.com/2010/1...

http://stories-etc.com/eye-candy.htm -- here is a similar version, actually closer to the one I received, although mine was stripped of all except the legend under each picture.

For our modern day minds, I find the Hubble and other NASA images of deep space evoke similar feelings of awe and majesty.

Zeke wrote: "Wishing you all well in your ascent into Paradise. Noted Lily's other reading in @2, Stephen King's 11/22/63. While not generally a Stephen King fan, I devoured this 900 page tome. Lily, I think you will find some thematic resonance with Divine Comedy--especially in the conclusion. "

Zeke wrote: "Wishing you all well in your ascent into Paradise. Noted Lily's other reading in @2, Stephen King's 11/22/63. While not generally a Stephen King fan, I devoured this 900 page tome. Lily, I think you will find some thematic resonance with Divine Comedy--especially in the conclusion. "LOL! Somehow, I can believe it! Looking forward to seeing if I can identify that "thematic resonance." As long as 11/22/63 is, it does read rapidly. (Haven't needed the dictionary feature on my ebook, let alone Internet background searches of mythology!) I think the only other King book I have read was Dolores Claiborne, but I am curious about his non-fiction book about writing.

@3 Lily wrote: "Even after divine revelation alongside his beloved (but denied) Beatrice, Dante somehow cannot flee from his desired pride as he seeks the crown of "a poet's triumph". Line 29.

He does, yes he does. He does a little soft-shoe and writes that he was "made worthy by the subject, and by you," but yes, I do sense he wants the "poet's triumph."

He does, yes he does. He does a little soft-shoe and writes that he was "made worthy by the subject, and by you," but yes, I do sense he wants the "poet's triumph."

Adelle wrote: "@3 Lily wrote: "Even after divine revelation alongside his beloved (but denied) Beatrice, Dante somehow cannot flee from his desired pride as he seeks the crown of "a poet's triumph". Line 29.

Adelle wrote: "@3 Lily wrote: "Even after divine revelation alongside his beloved (but denied) Beatrice, Dante somehow cannot flee from his desired pride as he seeks the crown of "a poet's triumph". Line 29. He does, yes he does. He does a little soft-shoe and writes that he was 'made worthy by the subject, and by you,' but yes, I do sense he wants the 'poet's triumph.'"

Well, as a reader and an "you" of what you quote above, I must admit to feeling a bit put down and rather inadequate (unworthy) by the opening lines of Canto II! LOL!

@4 Everyman wrote: "I'm thinking still about his invoking Apollo here. I thought that part of why he invoked the classical muses in the earlier sections was because he had Virgil, the classical author, as his guide. But here we're now in the pure realm of the Christian God, yet he's still back asking for the help of the pagan gods. I find that curious.

That stopped me, too. (No spoiler, but I had to mull that over.) (view spoiler)

That stopped me, too. (No spoiler, but I had to mull that over.) (view spoiler)

It might be that Dante believes ancient/pagan art to be an instrument of God. Virgil was sent on his mission to guide Dante by Beatrice, who was sent by Lucia, who was sent by the Virgin Mary.

It might be that Dante believes ancient/pagan art to be an instrument of God. Virgil was sent on his mission to guide Dante by Beatrice, who was sent by Lucia, who was sent by the Virgin Mary. The question I keep asking myself is, "Would excluding all of classical literature and history make Dante more "Christian"?

Thomas wrote: "The question I keep asking myself is, "Would excluding all of classical literature and history make Dante more "Christian"?

."

Of course not. But what seems so odd is that Dante isn't merely venerating the ancient poets and classical poetry (the instrument, if you will). I never appeal to the hammer (Oh, Hammer, help me!) to pound the nail.

He seems to be appealing directly to a god that the God of the Paradiso would (I think) require him to reject "as a god."

Yet Dante appeals to Apollo.

I happen to like it. But it does make me wonder about Dante's reasoning. Ah, too bad there isn't a notebook with all Dante's thoughts on the Divine Comedy written up like so many authors have.

."

Of course not. But what seems so odd is that Dante isn't merely venerating the ancient poets and classical poetry (the instrument, if you will). I never appeal to the hammer (Oh, Hammer, help me!) to pound the nail.

He seems to be appealing directly to a god that the God of the Paradiso would (I think) require him to reject "as a god."

Yet Dante appeals to Apollo.

I happen to like it. But it does make me wonder about Dante's reasoning. Ah, too bad there isn't a notebook with all Dante's thoughts on the Divine Comedy written up like so many authors have.

Remember that Statius said that he was led to Christ by Virgil. Dante seems to think that pagan excellence points ultimately to God.

Remember that Statius said that he was led to Christ by Virgil. Dante seems to think that pagan excellence points ultimately to God.

Lily wrote: ""..Well, as a reader and an "you" of what you quote above, I must admit to feeling a bit put down and rather inadequate (unworthy) by the opening lines of Canto II! LOL! ."

Oh my gosh, What does

Canto II say?

Guess I'd best get there.

Oh my gosh, What does

Canto II say?

Guess I'd best get there.

Thomas wrote: "The question I keep asking myself is, "Would excluding all of classical literature and history make Dante more "Christian"? ..."

Thomas wrote: "The question I keep asking myself is, "Would excluding all of classical literature and history make Dante more "Christian"? ..."My response is the same as Adelle's -- of course not! But, still Biblical commandments one and two sort of felt like they might be applicable in the context of calling for aid in describing a heavenly encounter:

http://godstenlaws.com/ten-commandmen...

Just as remarkable, perhaps equally so, was Dante's use of the analogy with Marsyas to describe the requisite emptying out of self to be adequate to the process demanded. I liked particularly Ciardi's comment (see msg. 2). It may be also that to some extent Dante is pleading that he does not want to anger or compete with God in making the revelations he is about to attempt -- but I feel now as if straining reasoning.

I still find myself scanning for parallels in the writings of St. Paul or the John of Revelations.

Adelle wrote: "He seems to be appealing directly to a god that the God of the Paradiso would (I think) require him to reject "as a god."

Adelle wrote: "He seems to be appealing directly to a god that the God of the Paradiso would (I think) require him to reject "as a god." Yet Dante appeals to Apollo. "

Good points, and I can't explain why he appeals to Apollo rather than God or Jesus. Unless this would be untoward, or somehow inappropriate for him to do in an epic poem.

A question for those familiar with Christian literature: Are there instances in literature up to Dante's time where a Christian poet has appealed to the Christian God for inspiration or guidance in the creation of a poem? (Or a Jewish poet, who would face the same problem. Perhaps even more so.)

Lily wrote: "Yes -- the Muses alone (Nisa) weren't going to be sufficient to help Dante express in words (to mere mortals) what he had experienced; he was turning instead to the god himself, Apollo (Cyrrha). Al..."

Lily wrote: "Yes -- the Muses alone (Nisa) weren't going to be sufficient to help Dante express in words (to mere mortals) what he had experienced; he was turning instead to the god himself, Apollo (Cyrrha). Al..."I've been struggling with the use of Apollo as well, but these two notes by Barbara Reynolds in the Sayers/Reynolds translation helped me to clarify my thinking.

First, a footnote:

-----

l. 13: Gracious Apollo! etc.: This is the beginning of the invocation. In Hell Dante invoked the Muses in general and in Purgatory first the Muses and then, in particular, Calliope, the Muse of Epic Poetry.

-----

And then, from the glossary:

-------

Apollo: son of Jupiter and Latona, who gave birth to him and his twin sister Diana on the island of Delos. Apollo was the god of song and the leader of the Muses (q.v.); hence Dante invokes his aid at the beginning of his most daring and arduous enterprise (Para. 1. 13 sqq. cf. ii. 8). As Apollo was the god of the Sun and Diana the goddess of the Moon, Dante speaks of them together as “the twin eyes of heaven” (Purg. xx. 132), and of the Sun and Moon as “the two children of Latona” (Para. xxix. 1). Apollo was also known as the Delphic god, from his temple and oracle at Delphi (Para. 1. 32; xiii. 25 and note; cf. Purg. xii. 31 and note.)

------

I think Dante is using Apollo not as a god, but as a muse. He is, after all, writing an epic. To tell this part of his journey, Dante invokes the greatest of the muses, the leader of them all, Apollo.

The other thing that is always in the back of my mind is my belief that the pagan gods and beliefs were not precursors to the Judeo-Christian ideas but rather broken images of them, broken since the Fall. I know that is not text-book anthropology, but that is what I believe.

Thomas wrote: "A question for those familiar with Christian literature: Are there instances in literature up to Dante's time where a Christian poet has appealed to the Christian God for inspiration or guidance in the creation of a poem? (Or a Jewish poet, who would face the same problem. Perhaps even more so.) ..."

Thomas wrote: "A question for those familiar with Christian literature: Are there instances in literature up to Dante's time where a Christian poet has appealed to the Christian God for inspiration or guidance in the creation of a poem? (Or a Jewish poet, who would face the same problem. Perhaps even more so.) ..."I won't say that I am familiar with Christian literature, but certainly the Abrahamic tradition has included prayer to invoke divine guidance and support for blessing upon worldly endeavors. As Anne Lamont so succinctly puts it -- "help, help, help", "thank you, thank you, thank you," and "Wow!" are probably the three basic petitions to the Divine.

I'm still trying to recall a passage in Paul's letters where he requests divine help or guidance in writing them. Surely there is something I am overlooking.

But, as far as Dante is concerned, I just find these passages re Apollo faintly amusing theologically and good story-telling nonetheless. (Someone has pointed out analogies between Apollo/Zeus and Christ/God, another possible source of intertextual meaning.)

@ 2 and 45 Lily wrote: "Just as remarkable, perhaps equally so, was Dante's use of the analogy with Marsyas to describe the requisite emptying out of self to be adequate to the process demanded

I found this @google.com/books:

"...a powerfully transformative agency which carries hearers or readers outside themselves (the root meaning of 'ecstasy') and 'draws out their souls'

It does seem to be what is being described by Dante, yes? And what a perfect time -- on entering Heaven --to feel ecstasy.

Book: Between Ecstacy and Truth; by Stephen Halliwell.

I found this @google.com/books:

"...a powerfully transformative agency which carries hearers or readers outside themselves (the root meaning of 'ecstasy') and 'draws out their souls'

It does seem to be what is being described by Dante, yes? And what a perfect time -- on entering Heaven --to feel ecstasy.

Book: Between Ecstacy and Truth; by Stephen Halliwell.

Adelle wrote: "'...a powerfully transformative agency which carries hearers or readers outside themselves (the root meaning of "ecstasy") and "draws out their souls"'

Adelle wrote: "'...a powerfully transformative agency which carries hearers or readers outside themselves (the root meaning of "ecstasy") and "draws out their souls"'It does seem to be what is being described by Dante, yes? And what a perfect time -- on entering Heaven --to feel ecstasy..."

Good stuff! Thanks!

Between Ecstasy and Truth: Interpretations of Greek Poetics from Homer to Longinus by Stephen Halliwell

Between Ecstasy and Truth: Interpretations of Greek Poetics from Homer to Longinus by Stephen Halliwell

Books mentioned in this topic

Between Ecstasy and Truth: Interpretations of Greek Poetics from Homer to Longinus (other topics)The Name of the Rose (other topics)

11/22/63 (other topics)

Ciardi's summary of canto one:

"CANTO I THE EARTHLY PARADISE The Invocation ASCENT TO HEAVEN The Sphere of Fire The Music of the Spheres DANTE STATES his supreme theme as Paradise itself and invokes the aid not only of the Muses but of Apollo. Dante and Beatrice are in THE EARTHLY PARADISE, the Sun is at the Vernal Equinox, it is noon at Purgatory and midnight at Jerusalem when Dante sees Beatrice turn her eyes to stare straight into the sun and reflexively imitates her gesture. At once it is as if a second sun had been created, its light dazzling his senses, and Dante feels the ineffable change of his mortal soul into Godliness. These phenomena are more than his senses can grasp, and Beatrice must explain to him what he himself has not realized: that he and Beatrice are soaring toward the height of Heaven at an incalculable speed. Thus Dante climaxes the master metaphor in which purification is equated to weightlessness. Having purged all dross from his soul he mounts effortlessly, without even being aware of it at first, to his natural goal in the Godhead. So they pass through THE SPHERE OF FIRE, and so Dante first hears THE MUSIC OF THE SPHERES."