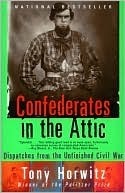

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Tony Horwitz

Read between

February 26 - March 11, 2021

“A Confederate-American—then and now—is simply anyone who’s against big government,” he said. “We as Southern Americans just want to be left alone.” “Yeah, the South wanted to be left alone—to oppress people!” a long-haired man shouted. “It was not about slavery!” a man with a rebel-flag T-shirt barked back. “It was states’ rights!” “Exactly. The right to own slaves. Tear the statues and plantations down!” “Should we tear down the Pyramids because they were built by slaves? And what about Washington and Jefferson? They owned slaves. Should we tear down memorials to them?”

Fort Sedgwick, dubbed “Fort Hell” because of the constant mortar and sniper fire aimed at it, now lay beneath the franchise hell skirting town. When we stopped to ask directions, a policeman said, “Where the Kmart is, that’s the approximate location.” Fort Mahone, another famous rampart, had been leveled, too, and now lay beneath a Pizza Hut parking lot. What remained of the battlefield offered an even starker preview of World War I than had Spotsylvania or Cold Harbor. During the 292-day stalemate here (roughly a quarter of the entire War), the armies constructed sandbagged bombproofs,

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

500 of the rebel mounts died of starvation during the army’s last three days in the field.

On April 9, 1865, Lee and Grant chatted about their service together in the Mexican War, then wrote out the terms of surrender. One of Grant’s aides, a Seneca Indian named Eli Parker, penned the formal document (and apparently pocketed Grant’s original draft, which he later sold). There were no theatrics or handing over of swords, though one aide was so overcome with emotion that someone else had to take over for him.

Southerners speak sentimentally

One of the most enduring misconceptions was that Lee’s surrender marked the end of the Confederacy. In fact, Lee surrendered only the 28,000 men under his command, leaving another 150,000 or so rebels in the field. The last land battle didn’t occur until a month later, at Palmito Ranch in Texas; it resulted, ironically, in a Southern victory. The last Confederate general to capitulate was Stand Watie, a Cherokee who surrendered his Indian troops on June 23rd.

less heralded virtue in America: reconciliation, mixed with what might be called sportsmanship. Grant frowned on celebration by his troops, and confessed to feeling sad and depressed “at the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered so much for a cause, though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which people ever fought.”

prideful defiance that quickly resurfaced in the post-War South, undoing so much of the reconciliation attempted at Appomattox.

Southern culture—that’s been bleached from the fabric of America,”

Most other neo-Confederates I’d met were romantics. The South they revered was hot-blooded, Celtic, heedlessly courageous; their poster boy was the Scottish clansman played by Mel Gibson in the splatterfest Braveheart. In their view, rationalism and technological efficiency were suspect Yankee traits, derived from a mercantile English empire that had put down the Scots and Irish.

Raised in New Haven, Connecticut, Dresch had displayed Copperhead tendencies from an early age.

“I move a lot of Ruffins,” he said. But his best seller by far was a T-shirt emblazoned with another fierce Confederate: Nathan Bedford Forrest, the “Wizard of the Saddle” and first Imperial Wizard of the Klan. “Lee, of course, used to be our best seller,” Dresch said. “But Forrest has eclipsed Lee fivefold in the last few years.” Dresch’s success in selling Forrest T-shirts gave commercial confirmation to the trend I’d sensed across the South: a hardening, ideological edge to Confederate remembrance. As Dresch put it, “Southerners are getting tired of taking it on the chin. They’re getting

...more

Forrest differed from Lee in another way, which helped explain his special appeal to working-class Southerners. Born to poverty and possessing little formal education, Forrest was a self-made man who became a wealthy slave trader before the War and rose from private to lieutenant-general during the conflict. “Come on boys,” Forrest once wrote in a recruiting ad, “if you want a heap of fun and to kill some Yankees.”

I sensed another kinship between Japanese and Southern culture; they shared a subtle, mannered code that often seemed contradictory and confusing to blunt, unmannerly outsiders like myself. As

Nor was Sherman’s March, which caused few civilian deaths, notably cruel by historic standards. As compared to the laying waste to Europe during the Thirty Years’ War, the routine massacres of Native Americans—or the murder and mayhem caused by Confederate guerrillas such as William Quantrill—Sherman’s treatment of Georgia civilians was almost genteel.

archives.” I wasn’t sure I caught the analogy. Leningrad seemed a long way from Point Lookout. But not to Joslyn. “To me, Civil War historians—Northern ones at least—are locking away the facts, too,” she said. “So little people like me have to keep the true story alive. That way, when the Revolution ends, and people come looking for the history, we can say, ‘Here it is. We kept it for you.’ ”

much the same from southern Virginia to western Arkansas: single-wide trailers with satellite dishes, low brick ranches with home-based businesses (beauty parlor, blade-sharpening, fish taxidermy, towing and recovery), white-frame churches with exclamatory sermon signs (“Presenting Jesus!”), flyspeck settlements—“Welcome to Forkland. Town of Opportunities. Pop 764”—abandoned to time and kudzu vines and men in bib overalls loitering before a faded Gas and Gro (“Tank and Tummy—Fill Em Up”). Then a small town with a stone rebel on the square and a “family restaurant” serving plate lunches

This is like twain harte. Trumpers are not new. The divide is not new. Whats new is the folks in Peoria (will it play) nows have big chain letters and megaphones: the internet. Then they got a demagogue to role model selfish immature speaking. Sad.

The former states of the Confederacy encompassed dozens of subcultures, from the Hispanic enclaves of Florida and Texas, to the Cajun country of south Louisiana, to the hardscrabble hills of Appalachia.

posts delineating the “deadline,” a perimeter inside the stockade that no prisoner could cross without risking gunfire from the guard towers (this was also the origin of the modern newspaper phrase).

their crude burrows caved in. Seven severely depressed prisoners were listed as having died of “nostalgia.” Sanchez said some despairing prisoners intentionally crossed the deadline, or drank from the toxic swamp surrounding the sinks.

But the biggest killers by far were diarrhea and dysentery. This was due not only to the camp’s lack of sanitation, but also to rations of rotted meat and coarse grain filled with shredded corncob, which irritated men’s already weak intestines. There was a cruel irony to this. Pointing to several belching smokestacks in the distance, Sanchez said the surrounding landscape was now mined for kaolin, a chalky mineral used to make Kaopectate. “You had thousands of men dying of the runs right on top of one of the world’s richest lodes of anti-diarrhea medicine,” he said.

But the biggest killers by far were diarrhea and dysentery. This was due not only to the camp’s lack of sanitation, but also to rations of rotted meat and coarse grain filled with shredded corncob, which irritated men’s already weak intestines. There was a cruel irony to this. Pointing to several belching smokestacks in the distance, Sanchez said the surrounding landscape was now mined for kaolin, a chalky mineral used to make Kaopectate. “You had thousands of men dying of the runs right on top of one of the world’s richest lodes of anti-diarrhea medicine,” he said.

This Southernized presentation seemed odd at a park administered by the U.S. government. Nor did the inclusion of POW stories from other wars strike me as altogether benign. Its impact was to dilute the Andersonville tragedy,

Andersonville lay on American soil and saw the death of 13,000 Americans in American custody.

efforts to exploit sectional passions were known in the late nineteenth century).

Towering over the main street was a granite shaft, inscribed WIRZ. Erected by the United Daughters of the Confederacy in 1909, its inscription said, “To rescue his name from the stigma attached to it by embittered prejudice.”

the UDC had originally composed an even more inflammatory message for the monument. It stated that the U.S. government, not Wirz, “is chargeable with the suffering at Andersonville” and listed doctored casualty rates at Civil War prisons.

Nor did the tragedy of Andersonville end with the camp’s closing in the spring of 1865. Almost three weeks after Appomattox, an overloaded steamship called the Sultana blew its boilers on the Mississippi River, drowning or burning alive an estimated 2,000 passengers in the worst maritime disaster in American history. Most of the casualties were freed prisoners from Andersonville, on their way home at last.

posed the question that had gnawed at me throughout my stay. Rather than proclaim Wirz a hero and blame Andersonville on the North, wouldn’t it be more fruitful—and historically factual—to present Civil War prison camps as a dark chapter of our history that neither side should be proud of? “That dog just won’t hunt,” Reynolds said. “Yankees started all this and we’ve got to resist with all available force, even if it seems one-sided.” “We don’t want forgiveness,” Clements added. “We want people to come over to our side.” “But why polarize the story?” I asked. “Aren’t you swinging the pendulum

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The museum’s evenhandedness mirrored Fitzgerald’s extraordinary history. The town’s namesake, Philander Fitzgerald, was a Civil War drummer who later became a pension attorney and publisher of a veterans’ newspaper in Indiana. When a severe drought hit the Midwest in the early 1890s, Fitzgerald concocted a novel idea. “Why not start a soldiers’ colony in the Southland and get all those old boys away from the bitter winters and drought?” Beth Davis explained.

modern memory by Southerners’ demonization of Reconstruction, or by Northerners’ smug stereotypes of a Klan-driven, Jim Crow South.

“History is lived forward but it is written in retrospect,” the English historian C. V Wedgwood observed. “We know the end before we consider the beginning and we can never wholly recapture what it was to know the beginning only.” Fitzgerald, for me, was a small reminder that the South’s post-War history wasn’t predestined to lead toward the strife and anger over the past I’d witnessed in so many other places across the South.

perfidious Yankees and the sanctity of the rebel flag.

Croyal, Malizie, Ardiller.

“I’ve taught two generations now, and this one is different,” she said. “They’re much thinner-skinned than kids used to be, but at the same time more insensitive to others.”

The Civil War, as I’d seen on countless battlefields, also marked the transition from the chivalric combat of old to the anonymous and industrial slaughter of modern times. It was, Walker Percy wrote, “the last of the wars of individuals, when a single man’s ingenuity and pluck not only counted for something in itself but could conceivably affect the entire issue.” This was true not only of generals, but also of men like Jedediah Hotchkiss, a geologist and mapmaker who scaled mountains to survey enemy positions before plotting several of the South’s most triumphant maneuvers. Today, the same

...more

Can you honor your Confederate ancestors without insulting others? What do you think?