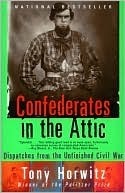

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Tony Horwitz

Read between

January 7 - January 10, 2019

There never will be anything more interesting in America than that Civil War never.

“I can’t forget Vietnam. But I hope the next generation won’t be hung up on it the way mine is,” he said.

“The way I see it,” Tarlton said, “they were fighting for their honor as men. They came from stock that was oppressed and they felt oppressed again by the government telling them how to live.”

It makes me wonder how human beings can possibly do that sort of thing to each other, and how you keep your spirit in that situation.

The whole notion that God was involved with one race putting down another, that’s going against the grain of a Christian nation. God

On the eve of the Civil War, white Charlestonians had the highest per capita income in America.

“Before the War, Southern women—white Southern women of means—were basically protected people, they didn’t do much,” she said. “But then the men went off to war and the women were left to take care of the homes, the businesses, the farms. They suddenly had to be self-reliant, and they found that they could be.”

“Growing up here, you can’t help being obsessed with the past,” he said. “Nothing ever dies in this town. It’s like a bottle of wine, just gets older and better.”

Jews began arriving in Charleston in 1695; until the early nineteenth century, the city had the largest Jewish population in the country, with a quarter of all American Jews living in South Carolina.

In the neo-Confederate view, North and South went to war because they represented two distinct and irreconcilable cultures, right down to their bloodlines. White Southerners descended from freedom-loving Celts in Scotland,

Ireland and Wales. Northerners—New England abolitionists in particular—came from mercantile and expansionist English stock. This ethnography

The eleven states of the Old Confederacy comprised the fifth-largest economy in the world.

“I don’t know if it’s the movies, the music, the music videos,” he said, “but there’s no respect for adults, or for human life.

“The past is dead; let it bury its dead, its hopes and its aspirations; before you lies the future. Let me beseech you to lay aside all rancor, all bitter sectional feeling, and to take your places in the ranks of those who will bring about a consummation devoutly to be wished—a reunited country.”

Reenacting had become the most popular vehicle of Civil War remembrance. There were now over 40,000 reenactors nationwide; one survey named reenacting the fastest-growing hobby in America.

From this vantage, the whole notion of a “battlefield park” seemed a contradiction in terms. Preserved here for eternity was peace, beauty and quiet—the precise opposite of the events memorialized.

“I don’t think that I could have written what I wrote in less than a hundred years after the War,” he said. “It took that long for North and South to see each other honestly through the dust and flame.”

Ten years after the War, the Mississippi River changed course, leaving Vicksburg high and dry and accomplishing in an instant what Grant fought for months to achieve: a way past the town.

Such yeoman often resented the plantation gentry, who could be exempted from military service if they owned twenty or more slaves, a loophole that prompted the famous Southern gripe: “a rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.”

Somewhere on the stretch of I-95 we’d driven earlier in the day, we’d crossed the invisible line that still separated North from South.

I couldn’t think of another city in the world that lined its streets with stone leviathans honoring failed rebels against the state.

The Army of Northern Virginia stacked its arms four years to the day after the South fired the War’s first shot on Fort Sumter. And the surrender was signed in the home of a woebegone farmer who had moved to Appomattox after fleeing his former house at Manassas, site of the War’s first land battle.

Instead, Appomattox honored a much rarer, less heralded virtue in America: reconciliation, mixed with what might be called sportsmanship. Grant frowned on celebration by his troops, and confessed to feeling sad and depressed “at the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered so much for a cause, though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which people ever fought.”