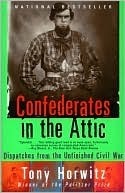

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Tony Horwitz

Read between

May 6 - May 20, 2016

We found the Civil War dead beside a denim plant with a billboard that said, “Bringing Fabric to Life!” On the other side of the cemetery stood a Frito-Lay warehouse.

“In school I remember learning that the Civil War ended a long time ago,” he said. “Folks here don’t always see it that way. They think it’s still half-time.”

As the meeting got under way, the twenty or so men in the room pledged allegiance to the Stars and Stripes. Then the color sergeant unfurled the rebel battle flag. “I salute the Confederate flag with affection, reverence and undying devotion to the Cause for which it stands,” the men said, effectively contradicting the pledge they’d just made to “one nation, under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.”

Roughly half of modern-day white Southerners descended from Confederates, and one in four Southern men of military age died in the War. For Yankee men, the death rate was about one in ten, and waves of post-War immigration left a far lower ratio of Northerners with blood ties to the conflict.

“It brings people together, like the War did,” he said. “I sit in a room with a doctor and pastor and such, and I don’t see them otherwise. We’re all together for the same reason.” The only other club to which he belonged was his factory’s softball team, which competed in North Carolina’s Industrial League.

I asked him if he thought “there” was better than “here.” “Not better,” he said. “I mean, my great-great-grandpap got his leg shot off. But I feel like it was bigger somehow.” Hawkins flipped through pages of Civil War pictures. “At work, I mix dyes and put them in a machine. I’m thirty-six and I’ve spent almost half my life in Dye House No. 1. I make eight dollars sixty-one cents an hour, which is okay, ’cept everyone says the plant will close and go to China.” He put the book back on the shelf. “I just feel like the South has been given a bum deal ever since that War.”

“I liked you right away last night,” Hawkins said. “There were all those doctors and such at the meeting. And you wanted to talk to me.”

Viewed through this prism, the War of Northern Aggression had little to do with slavery. Rather, it was a culture war in which Yankees imposed their imperialist and capitalistic will on the agrarian South, just as the English had done to the Irish and Scots—and as America did to the Indians and the Mexicans in the name of Manifest Destiny. The North’s triumph, in turn, condemned the nation to centralized industrial society and all the ills that came with it. Including car tires.

“Slavery was not all that bad,” she’d declared. “A lot of people were quite happy to be living on large plantations.” Chapman smiled sweetly. “Blacks just need to get over slavery,” she said, as though talking of the flu. “You can’t live in the past.”

Though black hostility to Confederate totems lay relatively dormant for two decades after the civil rights struggles of the early 1960s, it resurfaced in the mid-1980s and had escalated ever since. In 1987, the NAACP launched a campaign to lower Confederate flags from Southern capitols and eventually helped bring Alabama’s down. Black cheerleaders refused to carry the rebel flag at college ball games. Schools started banning “Old South” weekends and the playing of “Dixie.” In some cities, blacks called for the removal of Confederate monuments and rebel street names. And in 1993, black senator

...more

I asked her why she thought Michael had displayed the flag. Was it Southern pride? “He wasn’t into all the Confederate history and that,” she said, echoing her father. “He didn’t, like, dig into it.” “School spirit?” She smiled. “Michael was glad just to graduate from the place.” She said a few of Michael’s friends had started flying the flag from their pickups about the time he bought his truck. He decided to do the same. “Why?” Hannah shrugged. “He’d do anything to make his truck look sharp. The truck’s red. The flag’s red. They match.”

At the grave site, Confederate reenactors unfurled a rebel flag embroidered with the words “Michael Westerman Martyr” and fired their muskets in salute. Women dressed as Confederate mourners wept. The service concluded with the playing of “Dixie” and a eulogy by an SCV “commander” from Mississippi. Michael Westerman, he declared, had joined “the Confederate dead under the same honorable circumstances” as rebels who fell in battle. “He was simply one more casualty in a long line of Confederate dead of over one hundred thirty years of continuous hostility towards us and our people.”

What happened on that lonely road outside Guthrie wasn’t the portentous clash that outsiders—from the Southern League to the NAACP to journalists like me—imagined it to be. It seemed instead a tragic collision of insecure teenaged egos: one prone to taunts and loutishness, the other to violence and showing off. In a way, Michael Westerman and Freddie Morrow had a lot in common.

Foote’s mellifluous drawl and folksy stories on television had captivated me, as had his three-volume narrative history of the Civil War, still a hot-selling classic twenty years after its publication. The seventy-eight-year-old writer had become a curious phenomenon—a Civil War celebrity—and I’d somehow imagined that my cathode-tube acquaintance with him would make it easy to just chat about my travels, and to get his views on some of the impressions I’d formed.

“A civil war is a struggle between two parts of one nation, which implies that the South was never really separate or independent.”

The scale of Monument Avenue also amplified the weirdness of the whole enterprise. After all, Davis and Lee and Jackson and Stuart weren’t national heroes. In the view of many Americans, they were precisely the opposite: leaders of a rebellion against the nation—separatists at best, traitors at worst. None of those honored were native Richmonders. And their mission failed. They didn’t call it the Lost Cause for nothing. I couldn’t think of another city in the world that lined its streets with stone leviathans honoring failed rebels against the state. I wasn’t alone in harboring such thoughts.

...more

As the crowd dispersed, I posed the question that had gnawed at me throughout my stay. Rather than proclaim Wirz a hero and blame Andersonville on the North, wouldn’t it be more fruitful—and historically factual—to present Civil War prison camps as a dark chapter of our history that neither side should be proud of? “That dog just won’t hunt,” Reynolds said. “Yankees started all this and we’ve got to resist with all available force, even if it seems one-sided.” “We don’t want forgiveness,” Clements added. “We want people to come over to our side.” “But why polarize the story?” I asked. “Aren’t

...more

THE KNIGHTLIEST OF THE KNIGHTLY RACE WHO SINCE THE DAYS OF OLD HAVE KEPT THE LAMP OF CHIVALRY ALIGHT IN HEARTS OF GOLD.

As the group wandered off, I lingered to chat with Sandy and asked how she felt about guiding groups through this Old South shrine.

“It’s true what he says about the Jews,” Boone said. “They used to be on our side. But now a lot of them are bloodsuckers.” I let this go.

I realized I’d heard all this before. Honor the young foot soldiers. Take a stand for our rights. The litany of heroic deeds and fallen martyrs. It was the same mournful refrain that ran through dozens of Confederate observances I’d attended. Almost every sentence began to carry familiar echoes. Irma Jackson told of “marching all day and sleeping in the fields” between Selma and Montgomery—just as rebel soldiers had done in Virginia. She recalled other hallowed fields of battle—Birmingham, Tuscaloosa, Little Rock—which resonated with her audience as powerfully as Sharpsburg and Shiloh did for

...more

We went back and forth for half an hour. In essence, the students were saying that the Civil War had nothing to do with race or slavery—much the same argument made by neo-Confederates who saw the War through the prism of states’ rights.

“The Civil War is still going on,” Sanders said. “The only difference is that the Union army has betrayed us, too. So we’re fighting a confederacy up North and down South.”

I listened silently. Sanders’s message was the same refrain I’d heard across the South. My history and his-story. You Wear Your X, I’ll Wear Mine. Both races sealing themselves off from each other. I was relieved when the class finally ended.

Sanders frowned. “I prefer to deal with someone who admits their racism than with white liberals who hide it.” Then she launched into a tirade against white civil rights workers, black “sellouts” like Julian Bond, and “Jews who knock down men like Farrakhan.” “Jews don’t like Farrakhan because he calls them bloodsuckers,” I replied. “If you’re fighting racism, you shouldn’t have a leader who says racist things.” “Don’t tell us who our leaders should be,” Sanders snapped. “If you give up on a leader because of a few things he says, you can’t follow anyone.” “A few things?” I snapped back. “He

...more

But the South had changed on me, or I’d changed on it. My passion for Civil War history and the kinship I felt for Southerners who shared it kept bumping into racism and right-wing politics. And here I was in Selma, after holding my temper with countless white supremacists, losing it with a black woman whose passion I’d initially admired.

For me, this was the principal joy of reenacting. It restored my appreciation of simple things: cold water, a crust of bread, a cool patch of shade.