More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

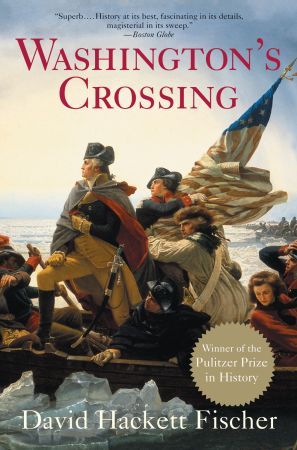

Emanuel Leutze also understood that something more was at issue in this event. The small battles near the Delaware were a collision between two discoveries about the human condition that were made in the early modern era. One of them was the discovery that people could organize a society on the basis of liberty and freedom, and could actually make it work. The ideas themselves were not new in the world, but for the first time, entire social and political systems were constructed primarily on that foundation. Another new discovery was about the capacity of human beings for order and discipline.

...more

The more we learn about Washington, the greater his contribution becomes, in developing a new idea of leadership during the American Revolution.

In the spring of 1776, the goal of the American Congress was not yet independence but restoration of rights within the empire.

They joined in the common cause but understood it in very different ways.

This great “mixture of troops” who were used to no control presented George Washington with a double dilemma. One part of his problem was about how to lead an army of free men. Another was about how to lead men in the common cause when they thought and acted differently from one another, and from their commander-in-chief.

From these men George Washington learned the creed he followed all his life. It valued self-government, discipline, virtue, reason, and restraint.

The philosophy that Washington learned among the ruling families of the Northern Neck was a modern idea. It was a philosophy of moral striving through virtuous action and right conduct, by powerful men who believed that their duty was to lead others in a changing world. Most of all, it was a way of combining power with responsibility, and liberty with discipline.

A major part of this code of honor was an idea of courage. The men around young George Washington assumed that a gentleman would act with physical courage in the face of danger, pain, suffering, and death. They gave equal weight to moral courage in adversity, prosperity, trial, and temptation. For them, a vital part of leadership was the ability to persist in what one believed to be the right way. This form of courage was an idea of moral stamina, which Washington held all his life. Stamina in turn was about strength and endurance as both a moral and a physical idea.

These men of the Northern Neck believed that people were not born to these qualities but learned them by discipline and exercise.

Washington thought of liberty in the Stoic way, as independence from what he called “involuntary passion.” He was a man of strong passions, which he struggled to keep in check. For him the worst slavery was to be in bondage to unbridled passion and not in “full possession of himself.”

He believed that only a gentleman of independent means could be truly free.

Part of his world was a hierarchy of race. In his early years Washington owned many slaves and actively bought and sold them. Before the Revolution he shared the attitudes of his time and place and fully accepted slavery, but after 1775 his thoughts changed rapidly. He began to speak of slavery as a great evil, and by 1777 he wrote of his determination to “get clear” of it. After much thought and careful preparation, he emancipated all his slaves in his will.

But Samuel Adams counted the votes and told his friends that “southern” delegates would support a Continental army only if a Virginian were to lead it.

Washington surrounded himself with a staff who shared his values.

These New England men were raised to a unique idea of liberty as independence, freedom as the right of belonging to a community, and rights as entailing a sense of mutual obligation.

In that process the Continental army, beginning with the Marblehead regiment, became the first integrated national institution in the United States.

One of its members wrote that they wore “strong brown linen hunting-shirts, dyed with leaves and the words ‘Liberty or Death,’ worked in large white letters on the breast.”

Here was another idea of liberty, different from the collective consciousness of New England towns, and the liberty-as-hierarchy among the Fairfax men, and liberty for African Americans among the Marblehead mariners. The backsettlers spoke of liberty in the first person singular: “Don’t Tread on Me.”

Washington acted quickly. A soldier from Massachusetts named Israel Trask watched him go about it. As the fighting spread through the camp, Washington appeared with his “colored servant, both on horseback.” Together the general and William Lee rode straight into the middle of the riot. Trask watched Washington with awe as “with the spring of a deer he leaped from his saddle, threw the reins of his bridle into the hands of his servant, and rushed into the thickest of the melees, with an iron grip seized two tall, brawny, athletic, savage-looking riflemen by the throat, keeping them at arm’s

...more

They had a major impact on the design of the Pennsylvania government, which in 1776 was the most radical in the world, with a unicameral legislature and more democracy than any other instrument of government.

Here was yet another way of thinking about liberty and freedom, in a manner that was true to the founding principles of Pennsylvania and to an idea of liberty that was inscribed on the Great Quaker Bell of Liberty in 1751. It bore a verse from Leviticus: “Proclaim Liberty throughout the land, unto all the inhabitants thereof.” This was an idea of liberty as reciprocal rights that belonged to all the people, a thought very different from the exclusive rights of New England towns, or the hierarchical rights of Virginia, or the individual autonomy of the backsettlers.

Here was another idea of liberty as a voluntary agreement, much like the commercial contracts these men made routinely in Baltimore and Annapolis.

Washington’s aide Colonel Samuel Blachley Webb wrote in his diary, “The Declaration was read at the head of each brigade, and was received with three Huzzas by the Troops—every one seemed highly pleased that we were separated from a King who was endeavoring to enslave his once loyal subjects. God grant us success in this our new Character.”67

He learned that the discipline of a European regular army became the enemy of order in an open society. To impose the heavy flogging and capital punishments that were routine in European armies would destroy an army in America.

In 1776, it was the largest projection of seaborne power ever attempted by a European state.

The British people took pride in its achievements but deeply feared the power of a standing army and kept it on a short leash.

Later generations condemned this “purchase system” as organized incompetence and institutionalized corruption, but its purpose was to ensure that British officers had a stake in their society and were not dangerous to its institutions.

Officers were appointed not by purchase but merit and trained as “gentlemen cadets” at the Woolwich Military Academy, which the army called “the Shop.” They studied algebra, trigonometry, quadratic equations, chemistry, engineering, and logistics and became an intellectual elite in the army.

Contrary to persistent myth, British soldiers were not an army of outcasts, criminals, and psychopaths. Most were farmers, weavers, and laborers with clean records.

Always it was thought that British soldiers should enlist as an act of choice.