More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

These men lived the rights they were defending, often to the fury of their commander-in-chief.

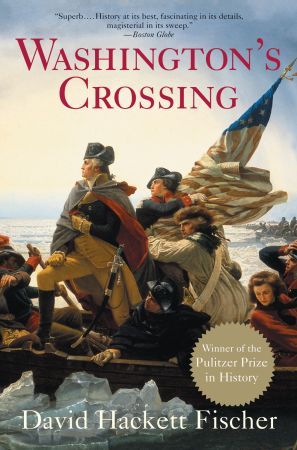

To study them with their general is to understand what George Washington meant when he wrote, “A people unused to restraint must be led; they will not be drove.”10 All of these things were beginning to happen on Christmas night in 1776, when George Washington crossed the Delaware. Thereby hangs a tale.

Men accustomed to unbounded freedom, and no controul, cannot brook the Restraint which is indispensably necessary to the good Order and Government of an Army.

when young George Washington lost his father, Lord Fairfax and Colonel Fairfax took a fostering interest in the young man. They became his mentors, and their houses were his schools.

From these men George Washington learned the creed he followed all his life. It valued self-government, discipline, virtue, reason, and restraint. Historians have called it a stoic philosophy, but it was far removed from the ancient Stoicism of the slave Epictetus, who sought a renunciation of the world, or the emperor Marcus Aurelius, who wished to be in the world but not of it. The philosophy that Washington learned among the ruling families of the Northern Neck was a modern idea. It was a philosophy of moral striving through virtuous action and right conduct, by powerful men who believed

...more

Much of this creed was about honor: not “primal honor,” not the honor of the duel, not a hair-trigger revenge against insult, or a pride of aggressive masculinity. This was

honor as an emblem o...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

A major part of this code of honor was an idea of courage. The men around young George Washington assumed that a gentleman would act with physical courage in the face of danger, pain, suffering, and death. They gave equal weight to moral courage in adversity, prosperity, trial, and temptation. For them, a vital part of leadership was the ability to persist in what one believed to be the right way. This form of courage was an idea of moral stamina, which Washington held all his life. Stamina in turn was about strength and endurance as both a moral and a physical idea.

These men of the Northern Neck believed that people were not born to these qualities but learned them by discipline and exercise.

Washington himself was a sickly youth, and he suffered much from illness. He was taught to strengthen himself by equestrian exercise and spent much of...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

By exercise Washington acquired extraordinary stamina and strength. The painter Charles Willson Peale remembered a moment at Mount Vernon in 1772 when he and other men were pitching a heavy iron bar, a popular sport in the Chesapeake. Washington appeared and, “without taking off his coat, held out his hand for the missile, and hurled it into the air.” Peale remembered that “it lost the power of gravitation, and whizzed through the air, striking the ground far, very far beyond our utmost efforts.” Washington said, “When

you beat my pitch, young gentlemen, I’ll try again.”

This modern creed of the Fairfaxes and Washingtons was linked to an idea of liberty. Washington thought of liberty in the Stoic way, as independence from what he called “involuntary passion.” He was a man of strong passions, which he struggled to keep in check. For him the worst slavery was to be in bondage to unbridled passion and not in “full possession of himself.”

George Washington also thought of liberty as a condition of autonomy from external dominion, but not as we do today.

“To treat them civilly is no more than what all men are entitled to,” Washington wrote, “but my advice to you is, to keep them at a proper distance; for they will grow upon familiarity, in proportion as you sink in authority.”

Washington had been taught to treat people of every rank with civility and “condescension,” a word that has changed its meaning in the modern era.

In Washington’s world, to condescend was to treat inferiors with decency and respect while mainta...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Public service diminished his wealth, and he was forced to sell large tracts of land to pay the expenses of his presidency.

Washington led his men in hard campaigning along the western frontier. In ten months his Virginia regiment fought twenty battles against the Indians and lost a third of its strength, but the civil population suffered less on the Virginia frontier than in other colonies. Washington was often in extreme peril, riding fearlessly with a few men through deep woods controlled by hostile Indians. Again he emerged unscathed.

But when he heard the news of the bloodshed on Lexington Green, he joined the Revolution and sent a letter of explanation to George William Fairfax. “Unhappy it is though to reflect,” he wrote, “that a Brother’s Sword has been sheathed in a Brother’s Breast, and that the once happy and peaceful plains of America are either to be drenched with blood, or Inhabited by Slaves. Sad alternative! But can a virtuous man hesitate in his choice?”30

These were his alternatives in 1775: liberty or slavery, virtue or corruption, honor or disgrace, courage or cowardice. In his own way this gentleman of the Northern Neck was as radical as any Revolutionist in the country. He was ready to “shake off all connections with a state so unjust and unnatural,” nearly four months before the Continental Congress was prepared to do so.

Washington was the available man: the only Virginian with experience of command and young enough to take the field. He was the only member of Congress who wore a uniform, and it suited him. One congressman wrote of his “easy soldier-like air.” His “modesty” and “independent fortune” were mentioned in his favor, a reassuring combination to these gentleman Whigs. Perhaps the decisive element was his air of Stoic calm; he was a man Whigs could trust with power. The Adams cousins proposed and seconded the nomination. Congress made it unanimous. Everyone was happy except George Washington, who

...more

Henry and said, “Remember, Mr. Henry what I now tell you: from the day I enter upon

command of the American armies, I date my fall, and the ruin...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

William Lee was said to be as fearless as Washington himself, and the two men “would rush, at full speed, through brake or tangled wood, in a style at which modern huntsmen would stand aghast.”

“I thought I was as warm a patriot as the best of them.”42 These New England men were raised to a unique idea of liberty as independence, freedom as the right of belonging to a community, and rights as entailing a sense of mutual obligation.

At first George Washington was not happy about the enlistment of African Americans, but after much discussion he worked out a sequence of compromises. The first was to allow African Americans to continue in the ranks but to prohibit new enlistments. The second was to tolerate new enlistments but not to approve them. By the end of the war, African Americans were actively recruited, and some rose to the rank of colonel in New England. Washington’s attitudes were different from those of Colonel Glover, but here again he worked out a dynamic compromise that developed through time. It also kept the

...more

Of all the units in the American army, none were more fascinating to their opponents. In the summer of 1776, British troops captured a rifleman and took him aboard the flagship of Admiral William Howe. British officers gathered to study the man, his clothing, and especially his weapon. They took a keen professional interest in the American long rifles that fired a small but lethal half-ounce ball with astonishing accuracy over great distances. Admiral Howe’s secretary Ambrose Serle noted that his weapon was “a handsome construction, and entirely manufactured in America.”47

Backcountry regiments from western Virginia were called “shirt men,” from their homespun backcountry hunting shirts made of sturdy tow cloth that had been “steeped in a tan vat until it became the color of a dry leaf.” In woods or high grass they were nearly invisible. Congress recommended on November 4, 1775, that their hunting shirts and leggings be adopted for the entire army.50

One backcountry company came from Culpeper County, in western Virginia on the east slope of the Blue Ridge Mountains. They called themselves the Culpeper Minutemen and mustered three hundred men with bucktails in their hats and tomahawks or scalping knives in their belts. One of its members wrote that they wore “strong brown

linen hunting-shirts, dyed with leaves and the words ‘Liberty or Death,’ worked in large white letters on the breast.” They armed themselves with “fowling pieces and squirrel guns” and marched to Williamsburg, where tidewater Virginians were not thrilled to see them. One Culpeper man remembered, “the people hearing that we came from the backwoods, and se...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Part of their “savage-looking equipments” may have been their flag. A sketch of it by a historian in the mid-nineteenth century shows the dark image of a timber rattlesnake, coiled and ready to strike, and the words “Don’t Tread on Me.” The same symbol was adopted at the same time by the backcountry militia of Westmoreland County in Pennsylvania and by other western units.52 Here was another idea o...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

among the Fairfax men, and liberty for African Americans among the Marblehead mariners. The backsettlers spoke of liberty in the first...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

backcountry r...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

were difficult men to lead. The social attitudes of a Fairfax gentleman did not sit well with them, and they were utterly defiant of discipline and order.

Washington had some of his deepest and most persistent differences with yet another unit, called the Philadelphia Associators. They were a volunteer militia that had begun as another of Benjamin Franklin’s many inventions in 1747, when Britain was at war with France and Spain. Quaker Pennsylvania had no militia and was unable to defend itself from privateers that cruised the coast. The Quakers

in the legislature were faithful to their testimony of peace and refused to act. In Philadelphia, Benjamin Franklin proposed to defend the town with a voluntary association, which men could freely join or not as they pleased. They were to supply their own weapons, elect their own officers, and choose a military council for short terms. Costs would be borne by voluntary subscription. Discipline would be done without corporal punishment, but only by “little fines . . . to be apply’d to the purchasing of drums, colours, etc.,” or “to refresh their weary spirits after exercise.” Incredibly, it

...more

There were tensions here, and much strife later in the Revolution, but in 1776 Philadelphians of different classes worked together in a common cause that belonged neither to the rich nor the poor. Here was yet another way of thinking about liberty and freedom, in a manner that was true to the founding principles of Pennsylvania and to an idea of liberty that was inscribed on the Great Quaker Bell of Liberty in 1751. It bore a verse from Leviticus: “Proclaim Liberty throughout the land, unto all the inhabitants thereof.”

This was an idea of liberty as reciprocal rights that belonged to all the people, a thought very different from the exclusive rights of New England towns, or the hierarchical rights of Virginia, or the individual autonomy of the backsettlers.

George Washington was dubious about the Associators. Their version of liberty was more radical in thought and act than any other unit’s in the army. But these men were devoted to the American cause and willing to fight in its defense. Later they would prove themselves to be exce...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

In 1776, Americans were less interested in pulling down a monarchy than in raising up a new republic. Washington’s leadership was becoming a major part of that process within the army. Men who came from different parts of the continent were beginning to understand each other. And Washington was learning how to lead them. He learned that the discipline of a European regular army became the enemy of order in an open society. To impose the heavy flogging and capital punishments that were routine in European armies would destroy an army in America. The men would not stand for that abuse. When the

...more

They in turn declared themselves “heartily sorry” and promised to reform, at least a little. Slowly this army of free men was learning to work together. They were also coming to respect this extraordinary man who was their leader, if not quite their commander-in-chief. They had come a long way toward forming an army, but was it enough? George Washington knew that they were about to meet some of the most formidable troops in the world, and the outcome was very much in doubt.71

The Royal Navy and British army had carried out a complex amphibious operation with harmony and high professional skill. The Americans were made to feel like helpless amateurs in the complex art of modern war.4

Supporting these troops were seventy British warships in American waters, half the fighting strength of the Royal Navy. In 1776, it was the largest projection of seaborne power ever attempted by a European state.

military observer thought that the British army on Staten Island was “for its numbers one of the finest ever seen.”

This was a modern professional army, with much experience of war.

Its fifteen generals were on the average forty-eight years old in 1776, with thirty y...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

By comparison, the twenty-one American generals who opposed them in New York were forty-three years old, with...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

In British infantry regiments, even privates had an average of nine years’ service in 1776. Most American troops had ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Except for the late unpleasantness in the colonies, the recent service of the British army was an experience of vi...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.