More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

February 15 - February 21, 2019

Though conversations come from my keen recollection of them, they are not written to represent word-for-word documentation; rather, I’ve retold them in a way that evokes the real feeling and meaning of what was said, in keeping with the true essence of the mood and spirit of the event.

At the age of nineteen, when Jarvis was rightly sent to San Quentin

an aversion—deeply buried but still present—to killing.

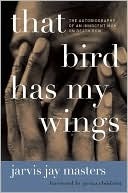

I pray that this autobiography of an innocent man does not end with the death chamber but with freedom.

picked up my pen filler, the only writing instrument allowed to an inmate in solitary confinement on death row.

favorites were the ones who nodded out on the couch

about to leave. So she stayed and held my hand again, talking to me gently while the other two women opened up my shirt. They kept saying, “Oh my God, oh my God.” The look in their eyes as they registered the condition of my young body began to scare me. I could tell they were near tears and at the same time angry.

I was too short for them to reach the floor.

Now I could run free and wild, without having to take care of my siblings.

people. I had never seen so many people in one single place. They were all black folks too!

He sat in his favorite cushioned armchair, and I sat on the carpet right between his legs.

had so many adults caring about me, wanting me to be part of their lives, that when Mamie and I prayed before my bedtime it took a long time to name all the people I needed to ask the Lord to watch over. “Oh, Jesus,” I began, “please look over Mr. Smith, Mrs. Jones, Mr. Williams and Nanny, also Mr. James and his dog, and Mr. Will and Clara….” I would go on and on until Mamie, kneeling beside me the whole time, would say, “Boy, can’t you just say ‘all God’s children’?” “But, Mamie, I’m almost finished,” I would answer. But then, having lost my place, I’d start all over again: “Mr. Smith, Mrs.

...more

she tried by her facial expressions to help other kids know the answers to Miss Clark’s questions.

Charlene asked for my sneakers, and it felt good to take them off and give them to her. At that time in our young lives, she and I wore the same size.

to believe in myself, whatever my mind clung to.

One day I was sitting at the piano, playing “Doe, a Deer” with all of my fingers,

We all tried to pretend it was an adventure.

A Rude Awakening

feeling it wasn’t nice to be calling the other team bad names.

“Yeah, but hey, don’t worry. You’ll get used to being hit!”

Even though we’d just met, I didn’t feel we were strangers. It was different from meeting new kids in school. We were more like train-jumpers who suddenly found themselves in the same railroad car; we shared an identity by the mere fact of being in “foster care,” a new term that would come to mean more than I had ever thought.

Florence hollered, “That’s enough!”

people of all different colors would help you: all you had to do was stick your hand out and they would put money into it.

slept out under the open skies. He said they’d sit around bonfires playing music and singing through the night.

Instead, I filled my mind with the idea of running away. I went to school every morning thinking about it. One day when the time was right, I would see my chance and go. This hope of all hopes kept me from feeling permanently condemned.

and to curl up as tight as a ball of yarn on the floor.

They made me feel sorry for myself when I hadn’t before.

and how to avoid cops by staying close to adults so the cops would think you were with them.

and no one would force you to eat something that you didn’t like.

Whenever I saw a hitchhiker, I’d watch to see if a car would stop and give him a ride. I was rehearsing my plan, getting closer and closer to taking the chance to free myself.

Mamie and Dennis.

close to a year later,

floor. I pulled a cushion off the sofa and held it like a shield as I curled up into a ball.

My whole body shook uncontrollably,

I was a gentle companion to myself. As I watched the reflections glowing into the night, life seemed so much kinder to me than it ever had with the Duponts. I wanted to ride on this bus for the rest of my life.

came to feel differently about people, depending on what they wanted to hear.

inviting me into my own sense of knowing a right from a wrong.

then I’ll take myself out of their rotten system by staying right where I am.”

They would cry when we told them what had happened to us. Then it was up to us to cheer them up.

“What the hell were you thinking out there, Masters?” whenever I made a mistake. That same someone would be the first to hug me and cheer me on when I played well. I craved this kind of attention.

We had no desire to take a scalpel and cut deep inside one another,

trying to figure out what was wrong.

Someone who could snore through anything was the envy of the dormitory: the peaceful sound of snoring was comforting, like a bedtime story. It always helped me sleep.

I was looking at Fred’s back, marked with burn scars that looked like dried lava pushed up against itself. I had never seen anything quite so gruesome before. The burns had left little of his natural dark skin. The exposed, healed flesh revealed all the reasons that we heard Fred’s scared screams deep into the night. Seeing it made me sad.

I was confused by the idea that I would get more time for violating the rules. I thought I was being placed at Boys Town permanently. How could I get more time? In order to stay here, I would have to act up and get into trouble. None of this made sense to me, and I didn’t have the nerve to ask where I would go if I stayed out of trouble.

and, worst of all, kids who boasted of killing dogs, cats, and other animals with knives before setting them on fire. These juvenile delinquents were homesick.

The pain of not having a home was in my face.

It was not that I wanted to kill myself; I wanted to live. But I also wanted to know that if things got too bad, I had an option. If I wanted to take my life at any time, I could do it.

I was putting myself in charge of why I was not going home, so having no home didn’t hurt the way pain does when you have no control.

“Who, me?” I pointed my finger at myself. “My name is Hen—…mine is Henry—” “Your name ain’t no Henry,” said Pablo, interrupting. “He’s Jay, and I’m Pablo.” Pablo and I had agreed that we weren’t going to tell anyone our real names. I wondered if it was the pot that made him change his mind.