More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

February 15 - February 21, 2019

In the beginning, the sickness I imagined repulsed me. I couldn’t take too much. I felt as if I were undergoing spiritual chemotherapy, attached to an intravenous tube

told me that I was to pack up all my belongings. After several years, I was being transferred to another cell in the adjustment center, “as a convenience move,”

Since other prisoners were also being moved, I didn’t take it personally. Maybe, I thought, it’s because of the construction work in the unit. I boxed up all my belongings, and on that same day I was moved into another cell.

Plus, man, all he did was beg, beg, beg for cigarettes

and coffee. That’s it, Jarvis! He begged me to death, you know?”

“Chill out over there, man. Let me handle this. Hey, if they want to move me again, well, hell, man, ain’t nothing to it but to do it, you know?”

found myself in the midst of an insane asylum. What saddened me most were the faces I recognized—people I had known in the past who had since gone crazy.

What If Hawk Was Right?

they stole his original brain and replaced it with a madman’s. Because I’ve always accepted his truths as his, we’ve been close. I can talk to Hawk for hours and not have a bored moment. He’s always full of theories about what is really going on.

Only later did I realize that the guards were using Hawk as a one-man cell-cleaning operation, moving him from dirty cell to dirty cell.

The worst part about being on the first tier was the windows. In my previous cells, I had been able to look far beyond the barbed wire, at the sunset. Closer to hand, in San Quentin’s grassy courtyard, I’d seen prisoners being baptized in the baptismal pool and heard the preacher’s voice calling out, “This man is giving his heart to Jesus.” But here on the first tier the windows were all painted over so you couldn’t see outside. That meant I was no longer able to reach beyond this place with my eyes. I didn’t know if the skies were blue or cloudy. I had to search for the time of day. These

...more

noise level continued to climb and I noticed that the cell was a little smaller than what I’d had before. For one thing, the ceiling was lower. Because all the cells are small, a little bit makes a big difference. On the first tier, the “bunk” is a cement block that measures six feet by three, and mayb...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

On the second and third tiers, the bunks are flat plates of steel bolted to the cell walls. The storage room under the bunk is a valuable feature in a tiny cell. Now I had to stack all my boxes on top of each other, which made my cell even smaller. I felt bunched up; I had no idea where to put anything. With the slab of cement lying lengthwise, there was no room to sort things out. In this first-tier c...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

find ways to get these materials down to the first tier, to people I knew could use them the most. I had known a lot of these guys before they’d lost their minds.

and I began silently reciting the Buddhist Red Tara mantra, Om Tare Tam Soha.

seems as if everyone you love on the outside is guaranteed to outlive you. They seem immortal. But Chagdud Rinpoche had recently died.

I’d never worn a seat belt before.

the prison industry buildings—passed by my window like a movie. I hadn’t been in a regular car in over twenty-two years.

even wished we’d find ourselves in a traffic jam for hours. I know such waiting usually frustrates people, but it is heavenly compared to San Quentin’s death row.

She acted as if she hadn’t noticed that I was a prisoner.

guards escorting me stood down from their “this is a hardened criminal” attitude.

Outside the prison people didn’t seem to talk to each other.

Everyone in the lobby kept their own space, even when they were seated next to each other. Nobody seemed to acknowledge that someone else was sitting right there—not even the kids! I would have been so hyper at their age, but they weren’t saying anything, not even bouncing around in their chairs. They were too well behaved, just frozen stiff.

“Have all these other cars been with us since we left San Quentin? Because I know I saw Dickerson walking out of the prison parking lot, and I’ve been wondering how he could have been sittin’ in the lobby when we arrived.” “You’re goin’ to have to ask Dickerson that,” he answered.

I also noticed the lack of social interaction among people, which was painful. Where has all of that gone—turning to talk to each other? I seriously wondered.

Drivers in the cars alongside us wouldn’t turn their heads to look at me, though some of them seemed to be talking to themselves. I could relate to that.

When the castlelike shape of San Quentin suddenly came into view, I had so much to think about, so much to reflect upon.

the voice of my own heartbeat telling me that I did not belong here in San Quentin or in any other prison—the voice of my longing to be free.

I’d just been wishing I could fly.

“Who wants to make a bet?” Hoop asked in his high, speedy voice. “I bet I can kill that damn bird over there with this ball.” I looked where he was pointing and saw a seagull about ten feet away, walking carefree on the asphalt of the yard, pecking for something to eat. “You guys wanna bet?” Hoop repeated as he jerked his arm back, aiming the ball right at the bird.

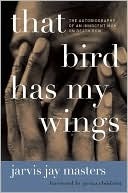

IT IS FOR THE young children who traveled with me through childhood that I have pried open my heart and relived memories I had suppressed in my soul’s stomach—wishing never to digest them—in order to write this book.

for sometimes only using the pen filler, as I do, so that our writing comes from the same place.

As a Buddhist practitioner, I feel so blessed to have Pema Chödrön in my life. No words can express all you have meant to me, Pema—both in my meditation practice and in my daily existence on death row. To have a precious and dear friend in a dharma teacher who on occasion can also care for me like a mother who knows what I think I can get away with—and refuses to let me—has been the biggest benefit to my practice. I am forever grateful to you, Pema, for all your encouragement to write this book so that it may be of benefit to others.