More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

S.C. Gwynne

Read between

May 7 - May 14, 2022

Though they did not know it at the time—the idea would have seemed preposterous—the sounding of “boots and saddle” that morning marked the beginning of the end of the Indian wars in America, of fully two hundred fifty years of bloody combat that had begun almost with the first landing of the first ship on the first fatal shore in Virginia. The final destruction of the last of the hostile tribes would not take place for a few more years. Time would be yet required to round them all up, or starve them out, or exterminate their sources of food, or run them to ground in shallow canyons, or kill

...more

Sherman’s chosen agent of destruction was a civil war hero named Ranald Slidell Mackenzie, a difficult, moody, and implacable young man who had graduated first in his class from West Point in 1862 and had finished the Civil War, remarkably, as a brevet brigadier general. Because his hand was gruesomely disfigured from war wounds, the Indians called him No-Finger Chief, or Bad Hand. A complex destiny awaited him. Within four years he would prove himself the most brutally effective Indian fighter in American history.

The Indians, mostly Kiowas, passed them over because of a shaman’s superstitions and had instead attacked a nearby wagon train. What happened was typical of the savage, revenge-driven attacks by Comanches and Kiowas in Texas in the postwar years. What was not typical was Sherman’s proximity and his own very personal and mortal sense that he might have been a victim, too. Because of that the raid became famous, known to history as the Salt Creek Massacre.5 Seven men were killed in the raid, though that does not begin to describe the horror of what Mackenzie found at the scene. According to

...more

Mackenzie and his men did not know much about Quanah. No one did. Though there is an intimacy of information on the frontier—opposing sides often had a surprisingly detailed understanding of one another, in spite of the enormous physical distances between them and the fact that they were trying to kill one another—Quanah was simply too young for anyone to know much about him yet, where he had been, or what he had done. Though no one would be able to even estimate the date of his birth until many years later, it was mostly likely in 1848, making him twenty-three that year and eight years

...more

By the time Mackenzie was hunting him in 1871, Quanah’s mother had long been famous. She was the best known of all Indian captives of the era, discussed in drawing rooms in New York and London as “the white squaw” because she had refused on repeated occasions to return to her people, thus challenging one of the most fundamental of the Eurocentric assumptions about Indian ways: that given the choice between the sophisticated, industrialized, Christian culture of Europe and the savage, bloody, and morally backward ways of the Indians, no sane person would ever choose the latter. Few, other than

...more

When it was all over, the soldiers discovered that Quanah and his warriors had made off with seventy of their best horses and mules, including Colonel Mackenzie’s magnificent gray pacer. In west Texas in 1871, stealing someone’s horse was often equivalent to a death sentence. It was an old Indian tactic, especially on the high plains, to simply steal white men’s horses and leave them to die of thirst or starvation. Comanches had used it to lethal effect against the Spanish in the early eighteenth century. In any case, an unmounted army regular stood little chance against a mounted Comanche.

That year General Antonio López de Santa Anna made an epic blunder that changed the destiny of Texas, and thus of the North American continent. On March 6, while flying the blood-red flag of “no quarter given,” some two thousand of his Mexican troops destroyed several hundred Texans at a small mission known as the Alamo in the town of San Antonio de Bexar. At the time it seemed like a great victory. It was a catastrophic mistake. He compounded it three weeks later at the nearby town of Goliad when he ordered his army to execute some three hundred fifty Texan soldiers after they had

...more

What happened next is one of the most famous events in the history of the American frontier, in part because it came to be regarded by historians as the start of the longest and most brutal of all the wars between Americans and a single Indian tribe.14 Most of the wars against Native Americans in the East, South, and Midwest had lasted only a few years. Hostile tribes made trouble for a while but were soon tracked to their villages where their lodgings and crops were burned, the inhabitants exterminated or forced to surrender. Lengthy “wars” against the Shawnees, for example, were really just

...more

She described what happened to some of the looters: Among [my father’s medicines] was a bottle of pulverized arsenic, which the Indians mistook for a kind of white paint, with which they painted their faces and bodies all over, dissolving it in their saliva. The bottle was brought to me to tell them what it was. I told them I did not know though I knew because the bottle was labeled.21 Four of the Indians painted their faces with the arsenic. According to Rachel, all of them died, presumably in horrible agony.

The preceding description may seem needlessly bloody in its details. But it typified Comanche raids in an era that was defined by such attacks. This was the actual, and often quite grim, reality of the frontier. There is no dressing it up, though most accounts of Indian “depredations” (the newspapers’ favorite euphemism) at the time often refused even to acknowledge that the women had been victims of abuse. But everyone knew. What happened to the Parkers was what any settler on the frontier would have learned to expect, and to fear. In its particulars the raid was exactly what the Spanish and

...more

As late as 1786, the Spanish governor of New Mexico still believed that the Comanche stronghold was in Colorado, when in fact they had established supremacy as far south as the San Saba country of Texas, some five hundred miles away.3 This is partly because the European mind simply could not comprehend the distances the average Comanche could travel. The nomadic range of their bands was around eight hundred miles. Their striking range—this confused the insurgent populations as much as anything—was four hundred miles.4 That meant that a Spanish settler or soldier in San Antonio was in grave and

...more

Those are the words of twenty-year-old Rachel Parker Plummer, written probably sometime in early 1839. She was referring to her memoir of captivity, and predicting her own death. She was right. She died on March 19 of that year. She had been dragged, sometimes quite literally, over half of the Great Plains as the abject slave of Comanche Indians, and then had logged another two thousand miles in what amounted to one of the most grueling escapes ever made from any tribe by any captive. To the readers of her era, the memoir was jaw-dropping. It still is. As a record of pure, blood-tinged,

...more

This sort of cruelty is a problem in any narrative about American Indians, because Americans like to think of their native aboriginals as in some ways heroic or noble. Indians were, in fact, heroic and noble in many ways, especially in defense of their families. Yet in the moral universe of the West—in spite of our own rich tradition of torture, which includes officially sanctioned torments in Counter-Reformation Europe and sovereign regimes such as that of Peter the Great in Russia—a person who tortures or rapes another person or who steals another person’s child and then sells him cannot

...more

Thus some chroniclers ignore the brutal side of Indian life altogether; others, particularly historians who suggest that before white men arrived Indian-to-Indian warfare was a relatively bloodless affair involving a minimum of bloodshed, deny it altogether.16 But certain facts are inescapable: American Indians were warlike by nature, and they were warlike for centuries before Columbus stumbled upon them. They fought over hunting grounds, to be sure, but they also made a good deal of brutal and bloody war that was completely unnecessary. The Comanches’ relentless and never-ending pursuit of

...more

Most important, the Indians themselves saw absolutely nothing wrong with these acts. For westering settlers, the great majority of whom believed in the idea of absolute good and evil, and thus of universal standards of moral behavior, this was nearly impossible to understand. Part of it had to do with the Comanches’ theory of the nature of the universe, which was vastly different from that of the civilized West. Comanches had no dominant, unified religion, or anything like a single God. Though in interviews after their defeat they often seemed to go along with the idea of a “Great Spirit,”

...more

Comanches all spoke the same language, dressed roughly in the same way, shared the same religious beliefs and customs, and led a common style of life that distinguished them from other tribes and from the rest of the world. That life, however, according to ethnographers Wallace and Hoebel, “did not include political institutions or social mechanisms by which they could act as a tribal unit.”31 There was no big chief, no governing council, no Comanche “nation” that you could locate in a particular place, negotiate with, or conquer in battle. To whites, of course, this made no sense at all. It

...more

Historians generally agree that there were five major bands at the turn of the nineteenth century. Most of the discussion in this book will focus on them. Each contained more than a thousand people. Some perhaps had as many as five thousand. (At its zenith, the entire nation was estimated at twenty thousand.) They were: the Yamparika (Yap Eaters), the northernmost band, who inhabited the lands to the south of the Arkansas River; the Kotsoteka (Buffalo Eaters), whose main grounds were the Canadian River valley in present-day Oklahoma and the Texas Panhandle; the Penateka (Honey Eaters), the

...more

All cooperated with one another on the friendliest of terms. All had, almost invariably, the same interests at heart. They hunted and raided together on an informal, ad hoc basis, and frequently swapped members. They never fought one another.33 They always had common interests, common enemies, and in spite of their decentralization acted with remarkable consistency when it came to diplomacy and trade. (Other tribes had band structures that were even harder for whites to understand. Sitting Bull, for example, was a member of the Sioux tribe, but his affiliation was with the Lakota, or western

...more

Then something remarkable happened. Starting around 1706, the Spanish authorities in Santa Fe began to notice a striking change in the behavior of their hated adversaries.2 They were, it seemed, disappearing, or at least moving off, generally to the south and west. Raiding had virtually stopped. It was as though a treaty of peace had been signed, but nothing of the sort had happened. The Spanish civil and military establishments began to realize that some sort of catastrophe had befallen the Apaches, though the extent of it would not be clear for years to come. In 1719 a military expedition to

...more

Almost all of this violence is lost to history. It generally took the form of raids on the villages of the Athapaskans, whose fondness for agriculture—ironically a higher form of civilization than the Comanches ever attained—doomed them. Crops meant fixed locations and semipermanent villages, which meant that the Apache bands could be hunted down and slaughtered. The fully nomadic Comanches had no such weakness. The details of these raids must have been horrific. The Apaches, who fought on foot, became easy marks for the mounted, thundering Comanches in their breechclouts and black war paint.

The Apaches were not their only victims. As the Comanches streamed south across the Arkansas River, flush with their astonishing mastery of the horse and their rapidly evolving understanding of mounted warfare, they discovered something else about themselves: Their war parties could navigate enormous distances using only natural landmarks. They could also do it at night. They were better at this, too, than anyone else. Before leaving, a war party would assemble and receive navigational instruction from elders, which included drawing maps in the sand showing hills, valleys, water holes, rivers.

...more

But in an era of grave misjudgments the greatest miscalculation of all took place in the year 1758. It happened on a lovely bend of a limestone river, amid fields of wildflowers in the hill country of Texas, about one hundred twenty miles northwest of San Antonio, and resulted in a grisly, era-defining event that became known as the San Saba Massacre. The massacre, in turn, would draw Spain into its greatest military defeat in the New World. Both came at the hands of the Comanches. There were many reasons for what took place, and many Spanish officials played a part. But the man to whom

...more

The San Saba Mission proposal was indeed, as Parrilla had suspected, a sham. The Lipans and other bands never had any intention of converting to Christianity. But what neither Parrilla nor any Spanish official had understood was the reason for the deception, and thus they had no idea of the extent of the treachery that had been perpetrated upon them. What had in fact happened, while the padres were busy shining up their sacramental vessels, was that the Comanche empire—an area far, far larger than any Spaniard suspected in those years—had arrived precisely on their doorstep.29 The Spanish had

...more

Parrilla now rode to the mission, where three priests and a handful of Indians and servants were protected by five soldiers, to beg Father Terreros to leave for the far greater security of the fort. Terreros refused, insisting that the Indians would never harm him. He was wrong. On the morning of March 16, 1758, mass was interrupted by the noise of whooping Indians. When the padres ran to the parapets, they saw a jaw-dropping sight: On all sides of the mission were gathered some two thousand warriors, many painted black and crimson, Plains Indians in the full regalia of war. They were mostly

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Considering what had happened in New Mexico and what was even now happening in Texas, he had what sounded like a wildly implausible goal: He wanted to make friends and allies of them. This he did. He gathered Comanche chiefs for peace talks, insisting that he speak with all of the bands that touched the western perimeter of the plains, and eventually insisting on appointing a single chief to speak for all the bands, something that had never happened before. Anza treated the Comanches as equals, did not threaten their hunting grounds, and refused to try to declare sovereignty over them. He

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

And fight them they did. The upshot of the Lamar presidency was an almost immediate war against all Indians in Texas. The summer of 1839 witnessed one of the most savage campaigns ever unleashed against Native Americans. The first target was the Cherokees, who had been pushed relentlessly westward over many decades from their homelands in the Carolinas. Many had landed in the piney woods and sandy riverbanks of east Texas, near the Louisiana border, where they had largely lived in peace with whites for almost twenty years. They were one of the five “civilized tribes,” and were indeed quickly

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Colonel William Fisher, one of the Texas commissioners, replied sharply: “I do not like your answer. I told you not to come here again without bringing in your prisoners. You have come against my orders. Your women and children may depart in peace. . . . When those prisoners are returned, your chiefs here present may likewise go free. Until then we hold you as hostages.”32 As he spoke, a detachment of soldiers marched into the courthouse and took up positions in the front and back. When the astonished Comanches finally figured out, through the terrified translator, what had been said, they

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The next day a woman who had not been wounded was given a horse and rations and told to ride to her people with the news of what happened. She was also to deliver an ultimatum: The survivors would be put to death unless the Comanche bands released the fifteen captives that Matilda Lockhart had told them about. If the woman did not return in twelve days, during which time there would be a full truce, “these prisoners shall be killed, for we will know that you have killed our captive friends and relatives.”37 If the Texans felt good about their bargaining position, they would soon learn

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Thus ended what became famous in the annals of Texas as the Council House Fight. Many Texans saw this as a sign that Texas, in the Lamar era, would brook no compromises with Indians. They were right. But the Texans had also made a terrible blunder that resulted immediately in the torture-killing of the rest of the hostages, set off a massive wave of retaliatory raids against settlements that ended up taking dozens of white lives, and destroyed for years whatever confidence the Comanches had in the integrity of the Texas government. One can only wonder what William Lockhart, whose lovely

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

But now many of the paraibos were dead. Some had been killed in the disastrous 1816 smallpox epidemic that swept through Comanche, Wichita, and Caddo villages and killed as many as four thousand Comanches,5 taking fully half of the estimated eight thousand band members at the turn of the nineteenth century.

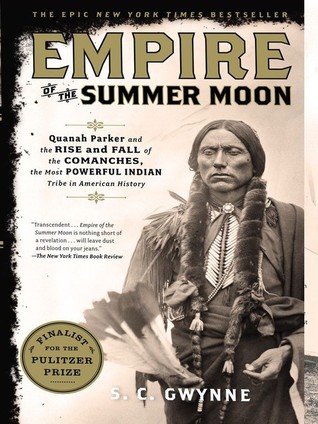

THERE IS HISTORY that is based on hard, documented fact; history that is colored with rumor, speculation, or falsehood; and history that exists in what might be termed the hinterlands of the imagination. The latter describes many of the nineteenth-century accounts of the captivity of Cynthia Ann Parker, the legendary “White Squaw” who chose the red man over the white man and a life of unwashed savagery over the comforts of “civilization.” Most are informed by a sort of bewildered disbelief that anyone, but especially a woman, could possibly want to do that. The

No one really knew what happened to her, and no one ever knew what she thought. People were thus free to indulge their prejudices. Though she became, in lore, legend, and history, the most famous captive of her era, the fact was that, at the age of nine, she had disappeared without a trace into the incomprehensible vastness of the Great Plains. Most captives were either killed or ransomed within a few months or years. The White Squaw stayed out twenty-four years, enough time to forget almost everything she had once known, including her native language, to marry and have three children and live

...more

As long as both of them lived, Banc and Minnie defended the Comanche tribe. Minnie Caudle “would not hear a word against the Indians,” according to her great-granddaughter. Her great-grandson said, “She always took up for the Indians. She said they were good people in their way. When they got kicked around, they fought back.”15 This is asserted against the brute facts of her own experience, which involved watching her captors rape and kill five members of her family. Banc Babb, against all reason and memory, felt the same way. In 1897 she applied for official adoption into the Comanche tribe.

But, as Williams soon discovered, this case was different. The Indians simply would not negotiate. In one account, he offered “12 mules and 2 mule loads of merchandise” for her, a princely sum for a single hostage. That was refused by the Indians who, according to a newspaper story, “say they will die rather than give her up.”21 Another had him offering “a large amount of goods and $400 to $500 in cash.”22 Still, the Indians refused. There were several reported versions of Cynthia Ann’s behavior. In one, she ran off and hid to avoid Williams and the others. In another, she “wept incessantly,”

...more

A letter written four months later from commissioners Pierce Butler and M. G. Lewis to the commissioner of Indian affairs in Washington cleared up the mystery. They suggested that the problem was not with Pah-hah-yuco or with the other headmen, who were more than willing to sell her for the right price. It was rather that “The young woman is claimed by one of the Comanches as his wife. From the influence of her alleged husband, or from her own inclination, she is unwilling to leave the people with whom she associates.”24 This was love, apparently, as difficult as that was for the white world

...more

That was bad luck. However she landed with them, it meant that she was thrown into the middle of a social and cultural disaster of epic proportions. To use a later historical parallel, it would have been like being adopted into a Jewish family in Berlin in 1932. There was not much future in it. She thus became the helpless victim of huge, colliding historical forces utterly beyond her control. What happened to the Penatekas in the 1840s destroyed them as a coherent social organization. They did not go down quickly and they did not go down without a fight—in their death throes they were in some

...more

Cholera was not subtle; it killed fast and explosively. Its incubation period was from two hours to five days, which meant that, from the moment of infection, it could and often did kill a healthy adult in a matter of hours. The disease is marked by severe diarrhea and vomiting, followed by leg cramps, extreme dehydration, raging thirst, kidney failure, and death.32 It was a horrible way to die, and a horrible thing to watch. The disease was transmitted by the ingestion of fecal matter, either directly or in contaminated water or food. Imagine a village of five hundred primitive people with

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

There, with the world crashing down around the southern Comanches, a son was born to Cynthia Ann and Peta Nocona. According to later interviews with his descendants, they named him Kwihnai, “Eagle.” If that is true, then the name Quanah is a nickname. Its meaning, too, is far from clear. According to his son Baldwin Parker in a later interview, the name comes from the Comanche “kwaina,” meaning “fragrant.”

Rachel died on March 19. Her infant son, Wilson P. Plummer, born on January 4, 1839, outlived her by two days.15 It is ironic that, after all she had suffered, and the thousands of miles she had traveled, her death was caused, indirectly, by her own father in what ought to have been the safety of her own home.

Comanches, meanwhile, carried a far more effective and battle-tested assortment of weapons: a disk-shaped buffalo-hide shield, a fourteen-foot plains lance, a sinew-backed bow, and a quiver of iron-tipped arrows. Their abilities with bow and arrow were legendary. In 1834, Colonel Richard Dodge, who was skeptical of the stories of their prowess, nonetheless observed that the Comanche “will grasp five to ten arrows in his left hand and discharge them so rapidly that the last will be on its flight before the first has touched the ground, and with such force that each would mortally wound a man at

...more

From the evidence that does exist, however, it is apparent that many young men died fighting Comanches in battles that must have been cruelly one-sided. Ranger John Caperton estimated that “about half the rangers were killed off every year” and that “the lives of those who went into the service were not considered good for more than a year or two.”23 He also wrote that, of the one hundred forty young men in San Antonio in 1839, “100 of them were killed in various fights with Indians and Mexicans.”24 (Most would have been killed by Indians.) Those are very large numbers in a town with a

...more

And so it was remarkable that this group of violent, often illiterate, and unmanageable border ruffians should give its full and unswerving allegiance to a quiet, slender twenty-three-year-old with a smooth, boyish face and sad eyes and a high-pitched voice who looked younger than his years. His name was John Coffee Hays. He was called Jack. The Comanches, who feared him greatly, called him “Capitan Yack,”30 as did the Mexicans, who put a high price on his head. He was the über-Ranger, the one everyone wanted to be like, the one who was braver and smarter and cooler under fire than any of the

...more

What happened next—seventy-five Penateka Comanches on fifteen Rangers, arrows and lances against repeating pistols—sounds like pure bloody pandemonium. Several Rangers were badly wounded. Their pistols, meanwhile, were dropping Indians from the saddle at an alarming rate. This stage of the fight lasted fifteen minutes. Then the Indians broke and fled. It became a running fight, and went for more than an hour on over two miles of rough terrain. Urged on by their heroic chief, the Indians kept rallying, regrouping, and attacking, only to be overwhelmed by the Rangers’ fire-spitting Colt

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

They weren’t fast enough. Half a mile from their house, the Indians reappeared. Now they seized Martha, who was nine months pregnant. While Ezra and his two children continued on, they dragged Martha back to a point about two hundred yards from the cabin. There she was gang-raped. When they were finished, they shot several arrows into her and then did something that was unusually cruel, even for them. They scalped her alive by making deep cuts below her ears and, in effect, peeling the top of her head entirely off. As she later explained, this was difficult for the Indians to do, and took a

...more

But the main problem with the Texas reservations was the white people who lived next to them. By 1858 white farms and ranches surrounded the reservations. And soon the whites were blaming the reservation Indians for raids that were being carried out by northern bands. In the fall of 1858 there were a series of savage raids all along the frontier—a settlement twenty-five miles from Fredericksburg was completely annihilated. Under the leadership of the Indian-hating newspaper editor John Baylor, settlers organized themselves and threatened to kill all of the Indians on both reservations. On

...more

We will never know how Cynthia Ann Parker felt in the weeks and months after her capture by Sul Ross. There are so few comparable events in American history. But it was painfully apparent from the earliest days that the real tragedy in her life was not her first captivity but her second. White men never quite grasped this. The event that destroyed her life was not the raid at Parker’s Fort in 1836 but her miraculous and much-celebrated “rescue” at Mule Creek in 1860. The latter killed her husband, separated her forever from her beloved sons, and deposited her in a culture where she was more a

...more

Champion had the same impression. “I don’t think she ever knew but that her sons were killed,” he wrote. “And to hear her tell of the happy days of the Indian dances and see the excitement and pure joy which shown [sic] on her face, the memory of it, I am convinced that the white people did more harm by keeping her away from them than the Indians did by taking her at first.”49 Whatever chance she may have had at contentment was destroyed in 1864 when Prairie Flower died of influenza and pneumonia.50 The little girl’s death shattered her. Now there was nothing left of her Comanche life but

...more

What happened next has been unnoticed or uncredited by the main chroniclers of Comanche history, largely because Quanah himself later forcefully denied that he was even at the Battle of Pease River or that his father had been killed there. Both assertions were untrue, and had to do with Quanah’s interest in cleansing what would have been a terrible stain on Peta Nocona’s record: The Comanches saw Pease River as a fiasco and a disgrace, and it had happened entirely on his watch. Quanah and Peanuts were at the camp because their mother said they were. She was frantic because of it. We also know

...more

Quanah became a war chief at a very young age. He did it in the traditional way, by demonstrating in battle that he was braver, smarter, fiercer, and cooler under fire than his peers. His transformation took place in two different fights. Both happened in the late 1860s, and both have been claimed as the vehicles of his elevation.

THE YEAR QUANAH became a warrior, 1863, was the bloodiest year in American history, though most of the blood that was shed had nothing at all to do with this ambitious Comanche boy who rode free on the western plains, stealing horses and taking scalps. The agent of death and destruction was the Civil War. That year it was transformed forever from the relatively brief, self-contained, regional conflict most people believed it would be into the malevolent, drawn-out, continent-girding affair that threatened to rip the country permanently apart. Eighteen sixty-three was the year of

...more