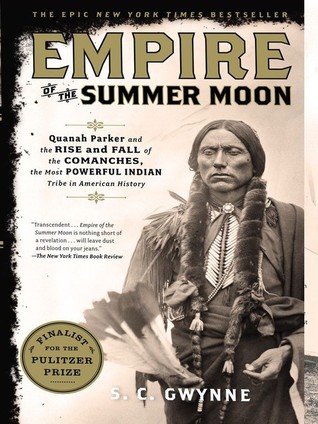

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

S.C. Gwynne

Read between

September 4 - September 14, 2020

Ranald Slidell Mackenzie, a difficult, moody, and implacable young man who had graduated first in his class from West Point in 1862 and had finished the Civil War, remarkably, as a brevet brigadier general.

the Comanche horsemen who rode up to the front gate of Parker’s Fort that morning in May 1836 were representatives of a military and trade empire that covered some 240,000 square miles,1 essentially the southern Great Plains.

They held sway over some twenty different tribes who had been either conquered, driven off, or reduced to vassal status. In North America their only peers, in terms of sheer acreage controlled, were the western Sioux, who dominated the northern plains.

Comanche could travel. The nomadic range of their bands was around eight hundred miles. Their striking range—this confused the insurgent populations as much as anything—was four hundred miles.4

It is one of history’s great ironies that one of the main reasons Mexico had encouraged Americans to settle in Texas in the 1820s and 1830s was because they wanted a buffer against Comanches, a sort of insurance policy on their borderlands. In that sense, the Alamo, Goliad, San Jacinto, and the birth of the Texas republic were the product of a misguided scheme to stop the Comanches.

Comanches had a remarkably simple culture. They had no agriculture and had never felled trees or woven baskets or made pottery or built houses. They had little or no social organization beyond the hunting band.

Abandoned by the Spanish, thousands of mustangs ran wild into the open plains that resembled so closely their ancestral Iberian lands. Because they were so perfectly adapted to the new land, they thrived and multiplied. They became the foundation stock for the great wild mustang herds of the Southwest. This event has become known as the Great Horse Dispersal.

In 1630, no tribes anywhere were mounted.25 By 1700, all Texas plains tribes had them; by 1750, tribes of the Canadian plains were hunting buffalo on horseback.

The Comanches adapted to the horse earlier and more completely than any other plains tribe. They are considered, without much debate, the prototype horse tribe in North America. No one could outride them or outshoot them from the back of a horse.

No tribe other than the Comanches ever learned to breed horses—an intensely demanding, knowledge-based skill that helped create enormous wealth for the tribe.

No other tribe, except possibly the Kiowas, so completely lived on horseback. Children were given their own horses at four or five.