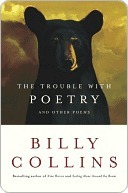

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

February 24 - February 27, 2023

and the poets are at their windows because it is their job for which they are paid nothing every Friday afternoon.

And there was I, up on a rosy-gray block of granite near a cluster of shade trees in the local park, my name and dates pressed into a plaque, down on my knees, eyes lifted, praying to the passing clouds, forever begging for just one more day.

the only emotion I ever feel, Debbie and Lynn, is what the beaver must feel, as he bears each stick to his hidden construction, which creates the tranquil pond and gives the mallards somewhere to paddle, the pair of swans a place to conceal their young.

It was a day in June, all lawn and sky, the kind that gives you no choice but to unbutton your shirt and sit outside in a rough wooden chair. And if a glass of ice tea and a volume of seventeenth-century poetry with a dark blue cover are available, then the picture can hardly be improved.

I could feel the day offering itself to me, and I wanted nothing more than to be in the moment—but which moment? Not that one, or that one, or that one, or any of those that were scuttling by seemed perfectly right for me. Plus, I was too knotted up with questions about the past and his tall, evasive sister, the future.

And so the priceless moments of the day were squandered one by one— or more likely a thousand at a time— with quandary and pointless interrogation. All I wanted was to be a pea of being inside the green pod of time, but that was not going to happen today,

but that hardly helps me echo the longing for immortality despite the roaring juggernaut of time, or the painful motif of Nature’s cyclical return versus man’s blind rush to the grave.

Then there are those like me who prefer to sleep on their sides, knees brought up to the chest, head resting on a crooked arm and a soft fist touching the chin, which is the way I would like to be buried, curled up in a coffin in a fresh pair of cotton pajamas, a down pillow under my weighty head. After a lifetime of watchfulness and nervous vigilance, I will be more than ready for sleep, so never mind the dark suit, the ridiculous tie and the pale limp hands crossed on the chest.

And the past and the future? Nothing but an only child with two different masks.

More like an empty zone that souls traverse, a vaporous place at the end of a dark tunnel, a region of silence except for the occasional beating of wings— and, I wanted to add as the sun dazzled your lifted wineglass, the sound of the newcomers weeping.

And here, I wish to say to her now, is a smaller gift—not the archaic truth that you can never repay your mother, but the rueful admission that when she took the two-tone lanyard from my hands, I was as sure as a boy could be that this useless, worthless thing I wove out of boredom would be enough to make us even.

That’s about it, but for the record, “Grimké” is Angelina Emily Grimké, the abolitionist. “Imroz” is that little island near the Dardanelles. “Monad”—well, you all know what a monad is.

But mostly poetry fills me with the urge to write poetry, to sit in the dark and wait for a little flame to appear at the tip of my pencil. And along with that, the longing to steal, to break into the poems of others with a flashlight and a ski mask.