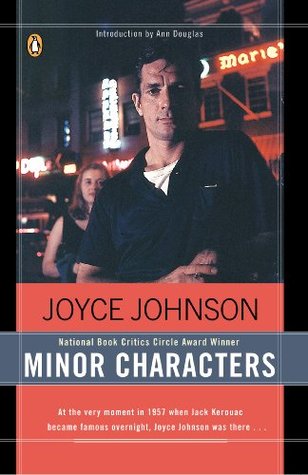

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Johnson met Kerouac much later, in early 1957, when she was twenty-one and he thirty-four, nine months before the publication of his best-selling novel On the Road (1957). A respected author in her own right, Johnson was a second-generation woman writer in an all-male movement; until recently, if she was considered a Beat at all, it was only by association, as Kerouac’s former girlfriend and present-day chronicler.

That in the process the Beats dismantled conventional ideas of masculinity, disavowing the roles of breadwinner, husband, and father and incorporating homosexual, even “feminine” traits into the masculine ideal, has seemed to many feminist critics less important than their sometimes openly misogynist ethos. Johnson was drawn to the Beats’ “pursuit of the heightened moment, intensity for its own sake,” but she soon learned that they found this intensity only with each other. The greatest love affairs of the early Beat Generation, whether sexual or platonic, transpired between men. Ginsberg and

...more

The woman writer who actually lived, as Johnson intermittently did, with a male Beat discovered that, since he fulfilled few, if any, of the conventional demands of his masculine role, she was sometimes freed from the small, incessant acts of subordination that then comprised daily life for a woman in a more traditional couple. In the mid-1950s, Kerouac could not support himself, much less a girlfriend, and Johnson notes the perverse but real pleasures of buying him dinner or lending him money;

The nineteenth-century suffrage crusade was born amid the male-dominated abolitionist movement; the feminist rebellion of the late 1960s came out of the often misogynist New Left.

Minor Characters records the cost the Beat Generation exacted of its most gifted women. Joan Burroughs and Elise Cowen didn’t survive, in part because they internalized their male Beat models too intimately; Hettie Jones postponed her own public career as a poet to further that of LeRoi Jones (later Amiri Baraka), then her husband. Yet, as Barbara Ehrenreich has argued, the male Beats provided an example of liberation for the feminists of the next decade,

It is important to remember that several of the Beat women writers, most notably Johnson and the poet Diane di Prima, were working in “Beat” directions before any of the major Beat works were published.

Memoirs of a Beatnik (1969), that “All the people who, like me, had hidden and skulked, writing down what they knew for a small handful of friends... would now step forward and say their piece ... they would, finally, hear each other. I was about to meet my brothers and sisters.”

The Beats’ primary purpose was to eliminate, by whatever method, the false note, the borrowed tone. As writers, what they shared was an insistence on immediate experience, a constant, palpably autobiographical focus, a distrust of conventional collective solutions, a keen comic eye for the incongruous and absurd, a restless push toward the Third World margins and urban back lots of industrial civilization, and a style intimately entangled with the arts of memory, honest at all costs, always alert to the funny, sad rhythms of the particular body moving through the strangeness of space and time.

“There were no women in this nighttime world,” Johnson realized; because of her sex, she would never have seen it if Jack hadn’t taken her there.

But Johnson never hitchhiked or bused around the Americas; she never made the journeys on which Kerouac’s art fed. Instead, the road of the Beat women became, in Johnson’s words, “the strange lives we were leading. We had actually chosen these lives for good reasons.”

the “ambitious woman,” who fancied herself the equal of men, constituted “an internal threat to freedom, worming its way into the heart of our society.” Although countless male commentators of the 1950s lamented that the new postwar suburban America had become a matriarchy in which men formed an “oppressed minority,” as Riencourt put it, feminism by any definition reached its lowest point in the twentieth century. Misogyny functioned as a cold war virtue.

Women had joined the workforce in record numbers during World War II, taking over jobs vacated by men serving overseas. Over three million women left or were forced out of the workplace at the war’s end, but most of them returned within a few years, if in less good positions and at lower salaries. (In 1950, female wages, down from a wartime high, were roughly half those of men.) By 1960, almost twice as many women worked as in 1940.

as Johnson explains the ethos in Minor Characters, “independence seemed the chief prerequisite for marriage.” In 1949, Frieda Miller, director of the Women’s Bureau, remarked that for women to work had become almost “an act of conformity.” Traditional forms of feminine self-assertion had been effortlessly co-opted into mainstream values.

College degrees made women better companions, not for themselves, but for their husbands.

Johnson entered her teens just as American entrepreneurs discovered teenagers as a separate and lucrative market.

In Minor Characters, Johnson quotes Allen Ginsberg’s dictum that “the social organization which is most true of itself to the artist is the boy gang”;

The Wayward Minor Laws, passed in New York in 1944 and 1945, stipulated that anyone aged sixteen to twenty-one who associated with “dissolute persons,” who was “disobedient to the reasonable and lawful commands of parents,” or who “desert[ed] his or her home” fell within the province of the Wayward Minor Court. The law covered males and females, but wayward girls were treated differently than wayward boys.

In the first article published on the Beat Generation, which Johnson had read with a thrill of recognition five years earlier, John Clellon Holmes said that “Beat” meant a “bottled eagerness for talk, for joy, for excitement, for sensation, for new truths... [the release of] buried worlds within.”

For Johnson to leave home, to sleep with a man on what in 1950s terms was their “first date,” at a time when birth control was imperfect if not unavailable, was to commit an “acte gratuit,” another early favored Beat term, a deliberate, decisive break with the established order. But in taking such a step, Johnson was not a candidate for glamorization, as Kerouac was when he left Columbia College in 1942 to write and hang out with drug addicts, petty thieves, and homosexual hustlers, “the Rimbauds and Verlaines of America on Times Square,” as he later called them.

Such artists were invaluable for cold war propaganda purposes. Whatever the impression left by the witch-hunts of Senator Joseph McCarthy, American rebels were living proof that, in contrast to the heavily regimented Soviet Union, creative individualism in extremis was allowed, even feted, in the United States.

Naturally, we fell in love with men who were rebels. We fell very quickly, believing they would take us along on their journeys and adventures. We did not expect to be rebels all by ourselves; we did not count on loneliness. Once we had found our male counterparts, we had too much blind faith to challenge the old male/female rules. We were very young and we were in over our heads. But we knew we had done something brave, practically historic. We were the ones who had dared to leave home. If you want to understand Beat women, call us transitional — a bridge to the next generation, who in the

...more

In 1957, Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac seemed to come from nowhere, though they had been writing their poetry and fiction underground since the beginning of the Fifties. It was just that no one had dared to publish them. They gave voice to the restlessness and spiritual discontent so many felt but had been unable to articulate. Powerful desires for a freer life were suddenly set loose by words with compelling, irresistible rhythms. The Beat writers found an audience grown so ripe that the impact was immediate.

The Beat movement lasted five years and caused many young men to go on the road in emulation of Jack Kerouac. Young women found the pursuit of freedom much more complicated. Nonetheless, it was my revolution. I didn’t go anywhere. I just left the New York neighborhood where I’d grown up and moved much farther downtown. I ended up accidentally with Kerouac in the center of the action, yet always felt myself on the periphery. I was much more of an observer than I wanted to be.

the gratuitous act was in fashion,

I know what became of Joan Vollmer. In 1944 and ‘45, her apartment on 115th Street was an early prototype of what a later generation called a pad — a psychic way station between the Village and Times Square, or between Morningside Heights and the Lower Depths, in the mental geography of those who came together there, lived there sporadically, made love, wrote, suffered, experimented with drugs, in those six big rooms where Joan had lived alone with a newborn baby until Edie introduced her to Jack. And Jack — seeing an affinity between Joan’s sharp, glittering wittiness and Bill Burroughs’s —

...more

Joan did match Burroughs wit for wit, and in other ways. She seems to have become a great reader of Korzybski, Spengler, Kafka, etc., startling the men by holding her own in their discussions. She matched him as well in her growing interest in drugs, staying high all day on Benzedrine-soaked cotton from nasal inhalers.

There was surely some hidden rock-bottom truth in that treacherous, all-night world of pushers and addicts, thieves and whores, that you couldn’t get at by reading Dostoevski or Céline — it had to be experienced directly.

She suddenly put her glass on her head, this drab housewife, and teasingly challenged Bill to shoot it off with his .38. He was a crack shot, and maybe they’d even gone through this William Tell routine on other festive occasions. Or maybe they hadn’t. Maybe it was a knowing, prescient act of suicide on Joan’s part, the ultimate play-out of total despair.

Lovers, initially strangers, become strangers again; the tie between parent and child pulls and twists for a lifetime, taking on the strangest forms.

Sheer, joyous movement. If it had been possible to remain in motion forever, never tiring, speeding away from each new encounter while it was still unsullied by the flagging of the first excitement, he might have been happy.

A joy-riding car thief, a yea-saying delinquent, a guiltless, ravenous consumer of philosophy, literature, women — all varieties of sexuality, in fact. An undecadent alter ego, Neal seemed.

Cassady loomed in Jack’s mind as archetypal, both his long-lost brother and the very spirit of the West in his rootlessness and energy.

in whose eyes it would have been an act of incomprehensible perversity for a young man to become deliberately classless if he had other options; in another few years, they would see it as positively un-American.

It’s from him we learn that a man’s longing is like an actual physical pain. Having created it even unintentionally, it seems you’re responsible for its assuagement.

A person pursuing Real Life must always be on the alert for fragments of what may seem meaningless information. From these fragments, which can only be gathered accidentally, one may eventually construct a whole piece of knowledge.

Their new crop of students — my generation — was called the Silent Generation. Our silence was common knowledge and was often cited in the pages of Time, Life, and the Sunday magazine of the New York Times. We were also called “other-directed” by David Riesman in The Lonely Crowd.

I was attracted to decadence, if that meant people like Alex and Elise. I had little respect for respectability. I was sure only cowardice kept me on the straight and narrow.

Entitled “This Is the Beat Generation,” it was a declaration of faith in a state of mind that, although new, according to this article, was totally familiar to me: “Everyone I knew,” Holmes wrote, “felt it in one way or another — that bottled eagerness for talk, for joy, for excitement, for sensation, for new truths. Whatever the reason, everyone of my age had a look of impatience and expectation in his eyes that bespoke ungiven love, unreleased ecstasy and the presence of buried worlds within.”

But wasn’t this “bottled eagerness” exactly what we felt? Could we be somehow more a part of the Beat Generation than of the Silent one we’d been born into chronologically?

That strangely used word Beat was immediately arresting. For one thing, it was blatantly ungrammatical. Did it mean “beaten”? Did it mean that there was a whole generation that moved to the vibrations of a particular rhythm — some kind of new music, perhaps, like the bebop Alex sometimes went down to Birdland to hear? The people Holmes described were in fact beaten down — down to “the bedrock of consciousness,” achieving a desperate beauty that seemed to be a kind of triumph. Holmes did not take credit for coining the phrase; with great scrupulousness he attributed it to a fellow writer and

...more

IN A “DREAM LETTER” from John Clellon Holmes recorded by Allen Ginsberg in 1954 are the words: “The social organization which is most true of itself to the artist is the boy gang.” To which Allen, awakening, writing into his journal, added sternly, “Not society’s perfum’d marriage.”

Everyone knew in the 1950s why a girl from a nice family left home. The meaning of her theft of herself from her parents was clear to all — as well as what she’d be up to in that room of her own.

The audience is unshockable, at one with the thin, intense young man in black raveled sweater who gets up on the tiny stage to read from his as yet unpublished manuscript. “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness...” Or if there is shock, it’s the shock of recognition popping off in a series of electrical synapses. “... starving hysterical naked / dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix, / angelheaded hipsters ...”

his hands, and the embrace of Kerouac. Jack, who has given Allen’s poem its title, is drunk again, as he was the first time Allen ever read Howl publicly — the October night at the Six Gallery when the San Francisco Renaissance was actually born.

I myself had come to place value on forgetting as a way of getting through life. Lovers you couldn’t forget were dangerous.

This was Jack Kerouac, whose reputation was underground. Like the others, he was said to frequent North Beach, a run-down area where there were suddenly a lot of new coffee shops, jazz joints, and bars, as well as an excellent bookstore called City Lights that was the center of activity for the poets. Thus several thousand young women between fourteen and twenty-five were given a map to a revolution.

America is waiting for prophetic poets. “Big trembling Oklahomas need poetry and nakedness,” Allen had told Jack in Mexico City, trying to rouse him from his lethargy, an exhaustion of spirit that’s overtaken him just now when they’re finally breaking through, when they’re about to become famous. Maybe even internationally, Allen keeps insisting to Jack, knowing his hunger for fame, knowing also his pitiable secret — the worm of envy hidden in his heart.

Peter and he could share women or love them separately or love other men. It seemed to make no difference — they possessed each other’s souls. They would always love each other.

Suddenly it was Jack’s moment. The “bottled eagerness” of the fifties was about to be uncorked. The “looking for something” Jack had seen in me was the psychic hunger of my generation. Thousands were waiting for a prophet to liberate them from the cautious middle-class lives they had been reared to inherit.

he, Allen, and Gregory Corso were interviewed by a reporter for a recently founded newspaper, the Village Voice. The article, when it ran, was entitled “Three ‘Witless Madcaps’ Come Home to Roost.” A hip putdown of three poetic stooges, it was a foretaste of some of the later publicity given the Beat Generation.