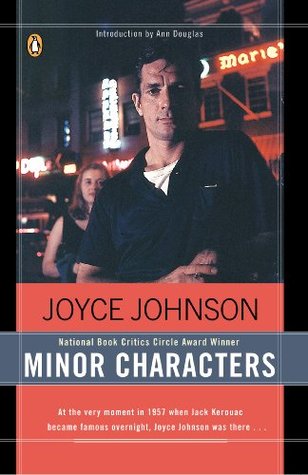

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

With a flash of exhilaration I saw that I could do it. I didn’t need Jack to take me, only to be at the other end of my destination.

It was disconcerting, though, to be left so free. Men were supposed to ask, to take, not leave you in place. I wanted to be wanted. Unlike Alex, Jack took what you gave him, asked no more. For Jack you didn’t have to be anything but what you were

Paint would rain down on the sized white surfaces — house paint, if there was no money for oils — colors running in rivulets, merging, splashing, coagulating richly in glistening thickness, bearing witness to the gesture of the painter’s arm in a split second of time, like the record of a mad, solitary dance. Or like music, some said, like bop, like a riff by Charlie Parker, incorrigible junky and genius, annihilated by excess in 1955, posthumous hero of the coming moment. Or like Jack’s “spontaneous prose,” another dance in the flow of time. For the final issue of Black Mountain Review, he’d

...more

I didn’t really know what to make of the paintings. What was I supposed to see? Where were the images? My college teachers had taught me always to look for images; but I found very few as recognizable as those in even the most difficult Picassos at the Museum of Modem Art. There was just all this paint. Sometimes you had the impression of tremendous energy or an emotion you couldn’t quite put into words; sometimes nothing came to you from the canvas at all.

Major or minor, they all seemed possessed by the same impulse — to break out into forms that were unrestricted and new.

He pressed a buzzer, and an editorial secretary, a very young woman like me, came in with coffee. “I want you to meet Joyce Glassman,” Hiram Haydn said. “And see if Bennett Cerf is in his office.”

I was going to be promoted from secretary to editorial assistant. It was an honor to get such a promotion. I knew it was possible to remain a secretary your entire working life. Perhaps someday I could even become an editor myself, although very few women got that far and the ones who had were all ladies of at least forty.

Jack lay down obscure for the last time in his life. The ringing phone woke him the next morning and he was famous.

Beaten? Bewilderedly Jack laughs and shakes his head, then with weirdly courteous patience launches into the derivation of the epithet — first uttered on a Times Square street corner in 1947 by the hipster-angel Herbert Huncke in some evanescent moment of exalted exhaustion, but resonating later in Jack’s mind, living on to accrue new meaning, connecting finally with the Catholic, Latin beatific. “Beat is really saying beatific. See?”

No one had much patience for derivations by 1957. People wanted the quick thing, language reduced to slogans, ideas flashed like advertisements, never quite sinking in before the next one came along. “Beat Generation” sold books, sold black turtleneck sweaters and bongos, berets and dark glasses, sold a way of life that seemed like dangerous fun — thus to be either condemned or imitated. Suburban couples could have beatnik parties on Saturday nights and drink too much and fondle each other’s wives.

“Beat Generation” had implied history, some process of development. But with the right accessories, “beatniks” could be created on the spot.

Meanwhile Jack filled the present. Fame was as foreign a country as Mexico, and I was his sole companion in its unknown territories. He’d quickly learned it was a country with sealed borders. You couldn’t leave it when you’d had enough of it, though it could cast you out when it had had enough of you.

middle-class children loosely defined as “artists,” who believed for a while, under the influence of all the new philosophy and rejecting the values of their own parents, that they had no use for money. Nomads without rucksacks,

The newcomers to the neighborhood regarded jobs the way jazz musicians regarded gigs — brief engagements. A steady gig (really a contradiction in terms) was valued chiefly as a means of getting unemployment insurance. The great accomplishment was to avoid actual employment for as long as possible and by whatever means.

It seemed entirely possible the newness and openness expressed in the poems, the paintings, the music, would ripple out far beyond St. Marks Place and the tables in the Cedar, swamping the old barriers of class and race, healing the tragic divisions in the American soul. Children of the late and silent fifties, we knew little of political realities. We had the illusion our own passions were enough. We felt, as Hettie Cohen Jones once put it, that you could change everything just by being loud enough.

Beatniks meant sex and filth and communism right in their neighborhood, and all respectability robbed from them forever, if they weren’t careful.

I made Jack come out to the sidewalk. Choked with pain, I searched for the worst words I could think of. “You’re nothing but a big bag of wind!” “Unrequited love’s a bore!” he shouted back. Enraged, we stared at each other, half weeping, half laughing. I rushed away, hoping he’d follow. But he didn’t.

Some of us defied death and reproduced. Never mind the mushroom clouds of doom! Rashly, perhaps, we peopled the uncertain future with our babies.

A museum of the cinema revives Pull My Daisy, the film Jack made with Robert Frank. With trepidation, I go to see it for the first time in twenty years. Its images are like solidified memory. There are Allen, Peter, and Gregory, benign pranksters — all beautiful young men. A familiar sooty light comes in through the loft windows. Dave Amram plays his horn. And Jack, the unseen narrator, is everybody all at once, making perfect, tender, absurd sense. But it’s too bad the women are all portrayed as spoilsports. Could I have remembered Jack’s voice? I keep trying to match it to the one I last

...more

I see the girl Joyce Glassman, twenty-two, with her hair hanging down below her shoulders, all in black like Masha in The Seagull — black stockings, black skirt, black sweater — but, unlike Masha, she’s not in mourning for her life. How could she have been, with her seat at the table in the exact center of the universe, that midnight place where so much is converging, the only place in America that’s alive? As a female, she’s not quite part of this convergence. A fact she ignores, sitting by in her excitement as the voices of the men, always the men, passionately rise and fall and their beer

...more

If time were like a passage of music, you could keep going back to it till you got it right.

Delinquents and Debutantes: Twentieth-Century American Girls’ Cultures,