More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

In the space of a few lines, Paul has called the Philippians to be part of a quite spectacular journey—namely, to live and to die like Christ, to model their lives so closely upon Christ that they bear within themselves the very mind of Christ. Yet he also calls them to “rejoice” (3:1), because in them, in their ordinary life together as congregation, God is enjoying them as divine representatives in the world. Great demands, but also great joy, at the wonder, at the adventure of being the church.

A colony is a beachhead, an outpost, an island of one culture in the middle of another, a place where the values of home are reiterated and passed on to the young, a place where the distinctive language and life-style of the resident aliens are lovingly nurtured and reinforced. We believe that the designations of the church as a colony and Christians as resident aliens are not too strong for the modern American church—indeed, we believe it is the nature of the church, at any time and in any situation, to be a colony.

The church is a colony, an island of one culture in the middle of another. In baptism our citizenship is transferred from one dominion to another, and we become, in whatever culture we find ourselves, resident aliens.

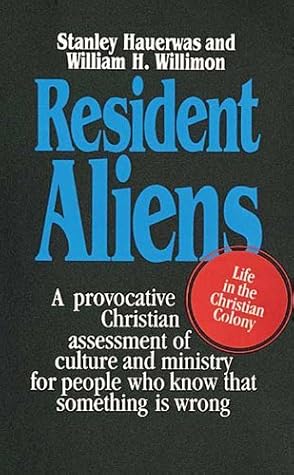

This book is about a renewed sense of what it means to be Christian, more precisely, of what it means to be pastors who care for Christians, in a distinctly changed world.

The world was fundamentally changed in Jesus Christ, and we have been trying, but failing, to grasp the implications of that change ever since. Before the Fox Theater opened on Sunday, we could convince ourselves that, with an adapted and domesticated gospel, we could fit American values into a loosely Christian framework, and we could thereby be culturally significant. This approach to the world began in 313 (Constantine’s Edict of Milan) and, by our reckoning, ended in 1963.

What we are saying is that in the twilight of that world, we have an opportunity to discover what has and always is the case—that the church, as those called out by God, embodies a social alternative that the world cannot on its own terms know.

Now our churches are free to embrace our roots, to resemble more closely the synagogue—a faith community that does not ask the world to do what it can only do for itself. What we once knew theologically, we now know experientially: Tertullian was right—Christians are not naturally born in places like Greenville or anywhere else. Christians are intentionally made by an adventuresome church, which has again learned to ask the right questions to which Christ alone supplies the right answers.

The project of theology since the Enlightenment, which has consumed our best theologians, has been, How do we make the gospel credible to the modern world?

This explains why, at least for a century, the church’s theology has been predominantly apologetic. The church did not want to duplicate the mistake we had made with Copernicus. When we took our first religion course in college, it was a course in how to fit the Bible into the scientific world view. We compared the archaic cosmology of Genesis to that of the true cosmology revealed by science. We learned how Moses could not possibly have written the Pentateuch nor Paul have written Ephesians. When we got to preaching, we were told to hold the Bible in one hand and today’s newspaper in the

...more

In Jesus we meet not a presentation of basic ideas about God, world, and humanity, but an invitation to join up, to become part of a movement, a people. By the very act of our modern theological attempts at translation, we have unconsciously distorted the gospel and transformed it into something it never claimed to be—ideas abstracted from Jesus, rather than Jesus with his people.

Not merely accepting ideas about Jesus, but following Him, being with Him, learning from Him to do the things He does.

Transform the gospel rather than ourselves. It is this Constantinian assumption that has transformed Christianity into the intellectual “problem,” which so preoccupies modern theologians. We believe that Christianity has no stake in the utilitarian defense of belief as belief. The theological assumption (which we probably wrongly attribute to our first apologetic theologians—some of the early Fathers) that Christianity is a system of belief must be questioned. It is the content of belief that concerns Scripture, not eradicating unbelief by means of a believable theological system.

The Bible’s concern is whether or not we shall be faithful to the gospel, the truth about the way things are now that God is with us through the life, cross, and resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth.

For Barth taught that the world ended and began, not with Copernicus or even Constantine, but with the advent of a Jew from Nazareth. In the life, death, resurrection, and ascension of Christ, all human history must be reviewed. The coming of Christ has cosmic implications. He has changed the course of things. So the theological task is not merely the interpretive matter of translating Jesus into modern categories but rather to translate the world to him. The theologian’s job is not to make the gospel credible to the modern world, but to make the world credible to the gospel. And that’s new.

Christianity is more than a matter of a new understanding. Christianity is an invitation to be part of an alien people who make a difference because they see something that cannot otherwise be seen without Christ. Right living is more the challenge than right thinking. The challenge is not the intellectual one but the political one—the creation of a new people who have aligned themselves with the seismic shift that has occurred in the world since Christ.

Each age must come, fresh and new, to the realization that God, not nations, rules the world. This we can know, not through accommodation, but through conversion.

We cannot understand the world until we are transformed into persons who can use the language of faith to describe the world right. Everyone does not already know what we mean when we speak of prayer. Everyone does not already believe that he or she is a sinner. We must be taught that we sin.

One cannot know what the world is without knowing that the “greatest thing in the history of the world” is not the bomb (then Truman, now certain anti-nuclear activists) but the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus.

Having challenged the notion that Christianity is fundamentally a system of belief, in this chapter we want to argue that Christianity is mostly a matter of politics—politics as defined by the gospel. The call to be part of the gospel is a joyful call to be adopted by an alien people, to join a countercultural phenomenon, a new polis called church. The challenge of the gospel is not the intellectual dilemma of how to make an archaic system of belief compatible with modern belief systems. The challenge of Jesus is the political dilemma of how to be faithful to a strange community, which is

...more

American ecclesiology, however, is not adequately described as a dichotomy between private and public. This is true not only because, since the seventies, increasing numbers of evangelicals have gone public with their social agenda, but because both conservative and liberal churches, left and right, assumed a basically Constantinian approach to the issue of church and world. That is, many pastors, conservative and liberal, felt that their task was to motivate their people to get involved in politics. After all, what other way was there to achieve justice other than through politics?

We believe both the conservative and liberal church, the so-called private and public church, are basically accommodationist (that is, Constantinian) in their social ethic. Both assume wrongly that the American church’s primary social task is to underwrite American democracy. In so doing, they have unwittingly underwritten the moral presuppositions that destroy the church.

What we call “freedom” becomes the tyranny of our own desires. We are kept detached, strangers to one another as we go about fulfilling our needs and asserting our rights. The individual is given a status that makes incomprehensible the Christian notion of salvation as a political, social phenomenon in the family of God. Our economics correlates to our politics. Capitalism thrives in a climate where “rights” are the main political agenda. The church becomes one more consumer-oriented organization, existing to encourage individual fulfillment rather than being a crucible to engender individual

...more

Our society, in brief, is built on the presumption that the good society is that in which each person gets to be his or her own tyrant (Bernard Shaw’s definition of hell: Hell is where you must do what you want to do). Most contemporary Christians cannot say enough good about rights. The way to ensure the “freedom of the individual” as well as to create a limited state is to protect the “rights of the individual.” It has thus become our unquestioned assumption that every human person has the “right” to develop his or her own potential to the greatest possible extent, limited only to the

...more

National governments are widely assumed to be responsible for and capable of providing those things which former generations thought only God could provide—freedom from fear, hunger, disease and want—in a word: “happiness.” (Lesslie Newbigin, The Other Side of 1984: Questions for the Churches

yet, to preserve themselves, all states, even democracies, must ask their citizens to die for them.

We are quite literally a people that morally live off our wars because they give us the necessary basis for self-sacrifice so that a people who have been taught to pursue only their own interest can at times be mobilized to die for one another.

It is against the backdrop of such social presumptions that we must see the weakness of the liberal church’s flaccid calls for “peace with justice.”

The moment that life is formed on the presumption that we are not participants in God’s continuing history of creation and redemption, we are acting on unbelief rather than faith. Does not the Bible teach that war and injustice arise precisely at the moment we cease testifying that our world is in God’s hands and therefore set out to take matters in our hands?

We argue that the political task of Christians is to be the church rather than to transform the world.

It is Jesus’ story that gives content to our faith, judges any institutional embodiment of our faith, and teaches us to be suspicious of any political slogan that does not need God to make itself credible. The church gives us the interpretive skills, a truthful understanding whereby we first see the world for what it is.

The church is the dull exponent of conventional secular political ideas with a vaguely religious tint. Political theologies, whether of the left or of the right, want to maintain Christendom, wherein the church justifies itself as a helpful, if sometimes complaining, prop for the state.

The loss of Christendom gives us a joyous opportunity to reclaim the freedom to proclaim the gospel in a way in which we cannot when the main social task of the church is to serve as one among many helpful props for the state.

Yet the problem remains within the structure of his categories—the temptation to believe that Christians are in an all-or-nothing relationship to the culture; that we must responsibly choose to be “all,” or irresponsibly choose to be sectarian nothing. When the church confronts the world with a political alternative the world would not otherwise know, is this being “sectarian”?

The church is the one political entity in our culture that is global, transnational, transcultural. Tribalism is not the church determined to serve God rather than Caesar.

In saying, “The church doesn’t have a social strategy, the church is a social strategy,” we are attempting to indicate an alternative way of looking at the political, social significance of the church. The church need not feel caught between the false Niebuhrian dilemma of whether to be in or out of the world, politically responsible or introspectively irresponsible. The church is not out of the world. There is no other place for the church to be than here.

We think that we could argue that being in the world, serving the world, has never been a great problem for the church. Alas, our greatest tragedies occurred because the church was all too willing to serve the world. The church need not worry about whether to be in the world. The church’s only concern is how to be in the world, in what form, for what purpose.

Yoder distinguishes between the activist church, the conversionist church, and the confessing church. The activist church is more concerned with the building of a better society than with the reformation of the church. Through the humanization of social structures, the activist church glorifies God. It calls on its members to see God at work behind the movements for social change so that Christians will join in movements for justice wherever they find them.

The confessing church is not a synthesis of the other two approaches, a helpful middle ground. Rather, it is a radical alternative. Rejecting both the individualism of the conversionists and the secularism of the activists and their common equation of what works with what is faithful, the confessing church finds its main political task to lie, not in the personal transformation of individual hearts or the modification of society, but rather in the congregation’s determination to worship Christ in all things.

For the confessing church to be determined to worship God alone “though the heavens fall” implies that, if these heavens fall, this church has a principle based on the belief that God is not stumped by such dire situations. For the church to set the principle of being the church above other principles is not to thumb our noses at results. It is trusting God to give us the rules, which are based on what God is doing in the world to bring about God’s good results.

It seeks to influence the world by being the church, that is, by being something the world is not and can never be, lacking the gift of faith and vision, which is ours in Christ. The confessing church seeks the visible church, a place, clearly visible to the world, in which people are faithful to their promises, love their enemies, tell the truth, honor the poor, suffer for righteousness, and thereby testify to the amazing community-creating power of God. The confessing church has no interest in withdrawing from the world, but it is not surprised when its witness evokes hostility from the

...more

The confessing church can participate in secular movements against war, against hunger, and against other forms of inhumanity, but it sees this as part of its necessary proclamatory action. This church knows that its most credible form of witness (and the most “effective” thing it can do for the world) is the actual creation of a living, breathing, visible community of faith.

As Jesus demonstrated, the world, for all its beauty, is hostile to the truth. Witness without compromise leads to worldly hostility. The cross is not a sign of the church’s quiet, suffering submission to the powers-that-be, but rather the church’s revolutionary participation in the victory of Christ over those powers. The cross is not a symbol for general human suffering and oppression. Rather, the cross is a sign of what happens when one takes God’s account of reality more seriously than Caesar’s. The cross stands as God’s (and our) eternal no to the powers of death, as well as God’s eternal

...more

We can’t go there because we no longer have a church that produces people who can do something this bold. But we once did.” We would like a church that again asserts that God, not nations, rules the world, that the boundaries of God’s kingdom transcend those of Caesar, and that the main political task of the church is the formation of people who see clearly the cost of discipleship and are willing to pay the price.

With a simple “Follow me,” Jesus invited ordinary people to come out and be part of an adventure, a journey that kept surprising them at every turn in the road. It is no coincidence that the Gospel writers chose to frame the gospel in terms of a journey: “And then Jesus went to,” “From there he took his disciples to,” “From that time he began to teach them that ...”

The church exists today as resident aliens, an adventurous colony in a society of unbelief. As a society of unbelief, Western culture is devoid of a sense of journey, of adventure, because it lacks belief in much more than the cultivation of an ever-shrinking horizon of self-preservation and self-expression.

In our day, unbelief is the socially acceptable way of living in the West. It no longer takes courage to disbelieve.

The Good News, which we explore here, is that the success of godlessness and the failure of political liberalism have made possible a recovery of Christianity as an adventurous journey. Life in the colony is not a settled affair. Subject to constant attacks upon and sedition against its most cherished virtues, always in danger of losing its young, regarded as a threat by an atheistic culture, which in the name of freedom and equality subjugates everyone—the Christian colony can be appreciated by its members as a challenge.

Yet when the church stakes out a claim, this implies that we are somehow satisfied with our little comer of the world, our little cultivated garden of spirituality or introspection, or whatever crumbs are left after the wider society has used reason, science, politics, or whatever other dominant means it has of making sense of itself.

Our biblical story demands an offensive rather than defensive posture of the church. The world and all its resources, anguish, gifts, and groaning is God’s world, and God demands what God has created. Jesus Christ is the supreme act of divine intrusion into the world’s settled arrangements. In the Christ, God refuses to “stay in his place.” The message that sustains the colony is not for itself but for the whole world—the colony having significance only as God’s means for saving the whole world. The colony is God’s means of a major offensive against the world, for the world. An army succeeds,

...more

We become part of a journey that began long before we got here and shall continue long after we are gone. Too often, we have conceived of salvation—what God does to us in Jesus—as a purely personal decision, or a matter of finally getting our heads straight on basic beliefs, or of having some inner feelings of righteousness about ourselves and God, or of having our social attitudes readjusted.

Faith begins, not in discovery, but in remembrance. The story began without us, as a story of the peculiar way God is redeeming the world, a story that invites us to come forth and be saved by sharing in the work of a new people whom God has created in Israel and Jesus. Such movement saves us by (1) placing us within an adventure that is nothing less than God’s purpose for the whole world, and (2) communally training us to fashion our lives in accordance with what is true rather than what is false.