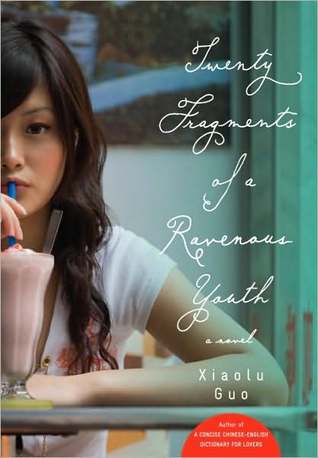

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

My youth began when I was twenty-one. At least, that’s when I decided it began. That was when I started to think that all those shiny things in life—some of them might possibly be for me.

livvy and 4 other people liked this

If I was going to miss out on anything, it was middle age. Be young or die. That was my plan.

Beijing was a brave new world for me, bright even at night. I wanted to rub up against it.

In my family, no one talked. My father never talked to my mother, my parents never talked to my grandmother, and none of them ever talked to me. In my village, people lived like insects, like worms, like slugs hanging on the back door of the house.

Zid and 1 other person liked this

Who would have thought an umbrella could play such a key role in the design of my future?

You can check any Chinese dictionary, there’s no word for romance. We say “Lo Man,” copying the English pronunciation. What the fuck use was a word like romance to me anyway? There wasn’t much of it about in China, and Beijing was the least romantic place in the whole universe.

“You don’t look like an actress. You’re not snooty enough.” Not snooty enough? I felt offended. But maybe he was right, otherwise why did I still only get lousy roles like “Woman walking over the bridge in the background” or “Waitress wiping some silly table”?

Anyway, Xiaolin was one year younger than me, so I assumed we were from the same generation. But when he said he had never once left Beijing, I changed my mind. It was clear he wouldn’t understand why I had left home. Perhaps we were from different generations after all.

If I had been thinking straight, I would have realised that Xiaolin wasn’t for me. His animal sign was the rooster, and they say the monkey and the rooster don’t mix. But I was young. I didn’t think about the future seriously.

A collective of three generations: his parents, his father’s mother, his two younger sisters and us, not forgetting two brown cats and a white dog—all sleeping and coughing in the one bedroom. A solid family life, no romance, and I knew there would never be any.

But most of the time Xiaolin was either angry or zombie-like. He was stuck in a rut. Get up, go to work, go to bed. Never any change.

There was no oxygen left in the room, I was worn out. It was like being back with the rotten sweet potatoes. I wanted to run and run and run.

There were no Chinese roses on the Chinese Rose Garden Estate, but there was plenty of rubbish. I had complicated emotions towards that place. It was like having a very ugly and smelly father, but you still had to live with him, you couldn’t just move out.

I’ve been blessed with cockroaches in every place I’ve lived in Beijing, but it was in the Chinese Rose Garden that I was truly anointed. My apartment was their Mecca.

The thing about my cockroaches, they were very cinematic, like the birds in that Alfred Hitchcock film. I was under constant attack. Singled out, they were weak and destructible, but collectively they were unbeatable.

In my Modern American Literature course, we had to recite Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. I could always recite that line: “Have you feared the future would be nothing to you?” And I took a “Crazy English” course, where they believed that you could master English by shouting very loudly.

all the money I was earning went towards my re-education. In exchange, I gained a load of certificates and diplomas. These credentials demonstrated that I was a useful member of society, that I was modern and civilised. Ah, finally, I was something.

Educating myself had allowed me to apply for permanent citizen status in Beijing. Now I was a person with multiple skills, all of which I was expected to dedicate to building the increasingly glorious reputation of my new home.

But then a day came when I completely lost trust in my adopted city—a day when I realised that, however useful I was to it, this bastard city could still reject me.

“Don’t worry, she deserved it anyway. She’s no good, that girl. Much too individualistic.”

I didn’t call, though. What would have been the point? Instead I sat down on my dirty carpet and watched Betty Blue. It was a very sad film. I couldn’t talk for a day afterwards.

Heavenly Bastard in the Sky, why the hell would I want to get out of bed in a Beijing winter anyway? There was a part of me that thought I should embrace the day, but a bigger part of me just wanted to crawl back into the dark night.

For me, it was old people who were responsible for all the shit things that had happened in China.

Half an orange, Heavenly Bastard in the Sky! That’s the only thing the poet ate on the day of his death. Suddenly I felt guilty. I felt my life was like a worm’s. No soul. I was a useless person compared with this poet.

The Chinese Film and Television Bureau has a rigid four-tier classification system for Directors: first-rate, second-rate, third-rate and fourth-rate. But the loss of face that would have to be endured by someone with Fourth-Rate Director printed on their business card meant that I had yet to meet one.

His film was based on the collective wedding ceremony that had been held in Beijing’s Forbidden City in the year 2000; 2,000 couples took part. The film would tell the story of one of these 2,000 couples as they walked up the red carpet together to welcome the dawn of a new era, a new century. However, he needed 1,999 other couples to act in supporting roles.

Female Number Three Hundred was a tall, good-looking woman who was planning to marry a short dwarf of a man (one metre forty centimetres) in the massive collective wedding. Everyone thinks she’s crazy, but she’s convinced she’s found her true love. The film would contain a tender portrait of their relationship. He reassured me that the dwarf treated his future wife like a princess.

I hmmmed three times. What were we talking about here? A short, ugly peasant Tom Cruise marrying a Chinese Nicole Kidman? “Does this woman have any lines to say?” I asked. “No, no, Fenfang, the set, the scenery, the costumes, eh?

I sat there staring at the box of noodles. How was it that in this cold city on this cold winter’s morning I could get a telephone call asking me to play a dwarf’s bride? How was it that I could sit on the floor of the 315th apartment in the Commercial Success Condominium and not remember how I got here?

I had always wanted to leave my village, a nothing place that won’t be found on any map of China. I had been planning my escape ever since I was very little. It was the river behind our house that started it. Its constant gurgling sound pulled at me. But I couldn’t see its end or its beginning. It just flowed endlessly on. Where did it go? Why didn’t it dry up in the scorching heat like everything else?

I used to imagine the source of the river. Some faraway, hidden cave that was home to a beautiful fairy. From there, the water flowed through our world to yet another world, a magical place close to heaven where lucky people lived, or animals perhaps—foxes maybe, or rabbits, owls, even unicorns. Wherever it was, it was not a place the people from my village could ever enter.

I was seventeen when I finally left that shithole for good. Thank you, Heavenly Bastard in the Sky.

Nothing changed, and nothing could change. The world felt frozen in front of me, like a family photo trapped in a frame. This landscape had imprisoned me since I was born.

And my father? Absent. I think we shared the same weariness of root vegetables.

Are you starting to see why I had to leave? Those fields had me on the verge of surrender.

On that day, they would tell themselves: today I will die. And they died as if they had never lived. They died like an ant dies. Who gives a damn when an ant dies?

The hills, the fields, the well and the river—I looked at these things I was leaving and already they were becoming my memories.

Oh, I wanted him to die.

I had this great urge to cry, but I didn’t want to cry alone. For a really good cry, I needed a man’s shoulder.

I lay on my bed. My body felt dead, my eyes would hardly open. I was vaguely aware of sunlight filtering through the orange curtains and a book in my hand. I lifted my arm and saw a rumpled copy of Kafka’s biography.

sounds were exhausting. I couldn’t face the day. I didn’t have the energy. Whenever I went out into the street, I would find others living positively and happily. They firmly believed in their lives, while I was always drifting and believed in nothing.

Facing the ocean, the warmth of spring will blossom, but only from tomorrow. Tomorrow, tomorrow, it would all happen tomorrow. And what about today?

A woman who looked like this brought absolutely no colour to a city. However long she sat in a bar or café, she’d find it impossible to engage even the loneliest bastard in conversation.

These emotional buckets emptied themselves on to the changing-room floor. Heartaches ran down into the mouldy drains.

The water was warm. I started to feel soothed, almost content. This always happened to me when I came to the pool. I felt close to the strangers around me. I liked to think they were here for the same reasons as me. That they were escaping their suffocating apartments, fleeing domestic arguments and newly made enemies, running from rejection and unrequited love. The water was a caress, a comfort. People felt blessed by it.

Kafka said, anyone who can’t come to terms with his life while he is alive needs one hand to wave away his despair and the other to note down what he sees among the ruins.

I became a person who was very good at hiding her emotions. Maybe that was why people thought I was heartless. Apparently my face often had a blank expression. Huizi, my most intellectual friend, would say, “Fenfang, yours is the face of a post-modern woman.”

At least I could eat, eat as much as I could, eat until the world didn’t owe me one penny.

Desire? That was a weird name for a car. I imagined that Tennessee Williams was from some shiny world swept by dramatic winds.

Everything around me was changing so fast—my apartment block, the local shops, the alleys, the roads, the subway lines. Beijing was moving forwards like an express train, but my life was going nowhere.