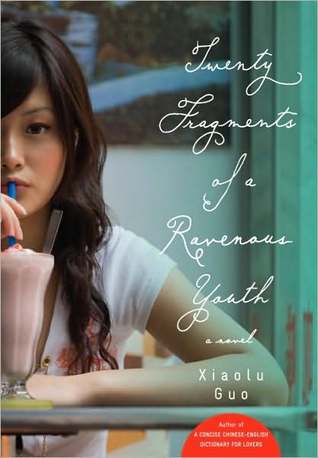

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Okay, so I was getting lots of work, but it was all the same. Woman Waiting on the Platform, Lady in Waiting, Bored Waitress. I was only in my twenties, but I felt seventy.

Once you’ve seen a shark, you always take care when you walk into the sea. I was terrified Xiaolin would come round to my flat again, and that next time it might be my leg he broke, not just the light. Ever since the day I told him I was thinking of moving out, Xiaolin had been involved in a systematic process of destruction.

That is a wounded body: a body that feels connected to someone who is no longer there.

I loved piracy. It was our university and our only path to the foreign world.

Everything was illegal, so no one could be bothered to do something legal, even the policemen.

When I looked up, the man with the long black hair had gone. He’d taken away his Duras. My Marguerite. He’d disappeared into Haidian with its huge population of young people and its rush of honking cars and bicycles.

Instead of signing myself in as a bit-part extra on twenty yuan a day plus a five-yuan lunchbox, I said I was a “Professional scriptwriter,” and went around the hotel in dark glasses and a long black coat like Keanu Reeves in The Matrix, carrying my laptop.

In the daytime, the hotel was deadly quiet. There was never anyone around. Eight hundred years could have passed and still no one would have knocked on the door asking for a room.

It might have been said that by escaping alone like this, I was not participating in the Community. That I, Fenfang, wasn’t contributing to the Greater Socialist Good. But I didn’t care. I wanted to hide away and write. I wanted to meet characters who would climb up my pen. I wanted to create a completely new world, inventing everyone and everything.

They would be thinking I was a prostitute. Why else would a young woman rent a room alone? It’s not standard in China. And, in China, anyone who does something “not standard” is immediately suspicious.

Beside me, the bell tower loomed, solemn and silent. It was so dark I couldn’t see a thing. Everything around me was shut and it was impossible to find out what the bell’s story was. This made me sad. Whenever I wanted to learn more about the places I belonged to, I found myself at a dead end.

“Fenfang, never look back to the past, never regret, even if there is emptiness ahead.” But I couldn’t help it. Sometimes I would rather look back if it meant that I could feel something in my heart, even something sad. Sadness was better than emptiness.

It felt like a scene from a film, a typical Chinese family scene. I could almost feel the Director hovering in the background, overseeing the set-up. Father, mother, daughter, sitting together on New Year’s Eve, eating and watching a famous actress singing communist songs on their newly bought TV.

I watched my father instead. He no longer looked like a travelling salesman. He looked old. It had never occurred to me that my father would get old. But here he was, shrinking, like all the other dried-up old people in the village. He had become even smaller than me. It clutched at my heart.

People here believed eating clams brought good fortune. If women ate them, they became fertile. On the table there was every type of clam you could fish from the East China Sea: Razor Clams, Turtle Clams, Hairy Clams. Heavenly Bastard in the Sky, I would become so fertile I could give birth to ten children, and I didn’t even know if I wanted one.

That New Year’s Eve, I felt as though time was flowing backwards. Fragments of the past returned too easily and it felt as if I’d never left. Despite the boom that had hit the place, everything still felt as it always had been. The same old vinegar, just in a new bottle.

I worried that this place would pull me back, that it would not let me go again. I worried that my will to survive might shrink and age here. I suddenly missed the cruel Beijing life. I missed my insecurity. I missed my unknown and dangerous future. Heavenly Bastard in the Sky, I missed the sharp edges of my life.

he noted down anything and everything that he found interesting, especially examples of Beijing slang. He loved the idea that “Second Breast” meant “mistress,” that “Sweeping Yellow” meant “prostitution is forbidden” and that “Cow’s Cunt” meant “absolutely wonderful.”

It seemed to me that Patton and I were similar: bored all the time. But he knew how to deal with his boredom better. Anyway, there was nothing sexual between Patton and me. We were like the “killers” in Wong Kar Wai’s film Fallen Angels. Killers can only ever be partners or enemies. Never lovers.

Anyway my favourite movie last week was The Sixth Sense. I loved the twist at the end, when you understand that Bruce Willis was dead all along . . .” “What?” I shouted, choking on a piece of duck. “I thought Bruce was alive! How could I have missed that? Maybe I was in the kitchen cooking dumplings, or in the toilet.”

Xiaolin felt like the only person in the world I was intimate with. We were like family—family members always hurt each other. And Ben was not my family, Ben lived for himself. A Western body. When Ben and I slept together, he could forget all about the love that was lying next to him in the dark. I felt he didn’t need much warmth from anybody. His own 98.9°F were sufficient for him. His spirit slept alone.

“So, you’re a woman writer. I, eh, I’ve never read anything by a . . . you know . . . woman before. And eh, don’t be angry, but let me tell you women can’t write. You tell me which great writer in China was a woman? There just aren’t any.

I don’t want to lose the beauty of my youth. I don’t want to see my body ageing. The cherry blossom chooses to die in one night. I want to do the same.

“Fenfang, I never expected you to be so young—or to have such a red face and hot hands. You look like you could play the Bloody Mary woman in your story.”

But before going anywhere, I needed to get hold of the script for a play, a play by Tennessee Williams called A Streetcar Named Desire. Heavenly Bastard in the Sky, I was determined to know what this Tennessee guy was all about.

I wanted to see if I could find the shiny things in life all by myself. I wanted to know if I could sleep by myself and not yearn to feel next to me the warmth of a 98.9°F man.

The last thing Huizi said to me was, “Fenfang, you must take care of your life.”

I am seventeen and it is a sweltering summer morning. I open the creaking shutters and look out at the hills. Rows of sweet potatoes stretch into the distance. The silent fields shimmer in the heat. I contemplate the pale clouds collecting in the sky. It’s time to leave. The unforgiving sun is melting my youthful body. I tell my seventeen-year-old self: Fenfang, you must take care of your life.