More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

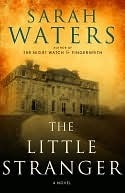

I first saw Hundreds Hall when I was ten years old. It was the summer after the war, and the Ayreses still had most of their money then, were still big people in the district.

recall most vividly the house itself, which struck me as an absolute mansion. I remember its lovely ageing details: the worn red brick, the cockled window glass, the weathered sandstone edgings. They made it look blurred and slightly uncertain—like an ice, I thought, just beginning to melt in the sun.

I was drawn to one of the dustless white walls, which had a decorative plaster border, a representation of acorns and leaves.

I first heard this excerpt on NPR in 2009. I bought the book the same day. These descriptions pulled me into the story. It reminded me of memories of a Spanish style house in Alabama, in which we lived in for a year. I was 8 or 9 years old at the time.

But the afternoon ran on without incident until the bluish drawing-in of dusk. My parents and I joined other Lidcote people for the long walk home, the bats flitting and wheeling with us along the lanes as if whirled on invisible strings.

The words used to drive me into secret rages, because on the one hand I wanted desperately to live up to my own reputation for cleverness, and on the other it seemed very unfair, that that cleverness, which I had never asked for, could be turned into something with which to cut me down.

Soon afterwards the Ayreses’ daughter died, and Mrs Ayres and the Colonel began to live less publicly. I dimly remember the births of their next two children, Caroline and Roderick—but by then I was at Leamington College, and busy with bitter little battles of my own.

With his death, Hundreds Hall withdrew even further from the world. The gates of the park were kept almost permanently closed. The solid brown stone boundary wall, though not especially high, was high enough to seem forbidding. And for all that the house was such a grand one, there was no spot, on any of the lanes in that part of Warwickshire, from which it could be glimpsed. I sometimes thought of it, tucked away in there, as I passed the wall on my rounds—picturing it always as it had seemed to me that day in 1919, with its handsome brick faces, and its cool marble passages, each one filled

...more

The house was smaller than in memory, of course—not quite the mansion I’d been recalling—but I’d been expecting that. What horrified me were the signs of decay. Sections of the lovely weathered edgings seemed to have fallen completely away, so that the house’s uncertain Georgian outline was even more tentative than before. Ivy had spread, then patchily died, and hung like tangled rat’s-tail hair. The steps leading up to the broad front door were cracked, with weeds growing lushly up through the seams.

His fingers felt queer against mine, rough as crocodile in some spots, oddly smooth in others: his hands had been burnt, I knew, in a wartime accident, along with a good part of his face.