More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

It was into this desolate triangle, sixteen years before, that her father had disappeared.

A letter from her dead father to her dead mother, written and stamped sixteen years ago.

“Hey, it’s lunchtime, and once I lock up I’m going to grab a burrito. Care to join me?” Nora shook her head. “Got to get back to my office, thanks. I’ve got a lot of work to do this afternoon.” “I’ll consider that a raincheck,” Smalls said. “Too bad we live in the desert.” Nora went out the door to the sound of harsh laughter.

“Thurber?” she called. She thought of going outside to call for him, but changed her mind immediately: Thurber was the most domesticated animal on the planet, for whom the great outdoors was something to be avoided at all costs.

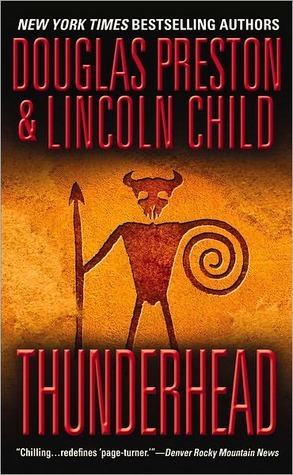

“Anasazi lightning stones,” he said in his quiet voice. “Are they real?” asked Holroyd, taking them from Nora and holding them to the firelight. “Of course,” said Goddard. “They come from a medicine cache found in the great kiva at Keet Seel. We used to believe the Anasazi used them in rain ceremonies to symbolize the generation of lightning. But we aren’t sure anymore. The carved spiral represents the sipapu. But then again, it might represent a water spring. Again, nobody knows for sure.”

“There are some who do not believe the lost city of Quivira exists. They think this expedition is foolhardy, that I’m throwing my money away. There is even fear this will prove an embarrassment to the Institute.” He paused. “But the city is there. You know it, and I know it. Now go and find it.”

Suddenly her knees grew weak and she dropped slowly to the ground. Seated, she continued to stare across the valley. There was a rustling sound, and Sloane knelt down beside her. “Nora,” came the voice, the slightest trace of irony leavening the reverence, “I think we’ve found Quivira.”

It was the cosmography that still ran through most present-day southwestern Native American religions: the black mountain in the north, the yellow mountain in the west, the white mountain in the east, and the blue mountain in the south.

She realized, with a small shock, that this was the first time she had heard him call her by name instead of the odious “Madame Chairman.” And although she couldn’t analyze it—and didn’t have the time, even if she felt inclined to do so—a part of her was pleased to think Smithback was concerned about how she felt about him.

“If you call coming out here, praying, and even fasting for a while, a vision quest, then I suppose that’s what it is. I don’t do it for visions, but for spiritual healing. To remind myself that we don’t need much to be happy. That’s all.”

What you’re doing, digging in that city, is going to kill you if you don’t get out, right now. Especially now that . . . they’ve found you.” “They?” Smithback asked. “Who’s ‘they’?” Beiyoodzin’s voice dropped. “The spotted-clay witches. The skinwalkers. The wolfskin runners.”

Then Black slowly turned his eyes toward Sloane. In his pain and unutterable dismay, he could not quite comprehend that her face, instead of despair, reflected shining, complete vindication.

Smithback looked at her. “Nora,” he said again. “You know, after all that’s happened between us . . . well, I’d really like to tell you how I feel.” She stared at him. Then, gliding closer, she took his hand in hers. “Yes?”

His lips parted in a feeble grin. “I really feel like shit,” came the dry whisper. Nora shook her head, laughing despite herself. “You’re incorrigible.”