More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

June 10 - July 6, 2024

Men did not especially like the idea of being treated the way they’d treated women

Up through 1880, the age of consent in America was generally age ten or twelve.

By 1887, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union had begun protesting this standard, advocating to have “the age at which a girl can legally consent to her own ruin be raised to at least eighteen years.”

This request was initially laughed at, with legislators suggesting joke amendments proposing the “age of consent be raised to eighty-one years, that all girls be required to wear a chastity belt, or to mandate that all women must consent to sex after the age of eighteen years.”

bound for New Orleans, accompanied by Shackford’s young son from his prior marriage. On the voyage, the son fell off the boat and drowned. This tragic accident is horrifying in and of itself, but even more disturbing is the fact that Shackford “received the intelligence unmoved, while [Cordelia], to whom the child had become endeared, grieved for him.”6 This should’ve been a very red flag.

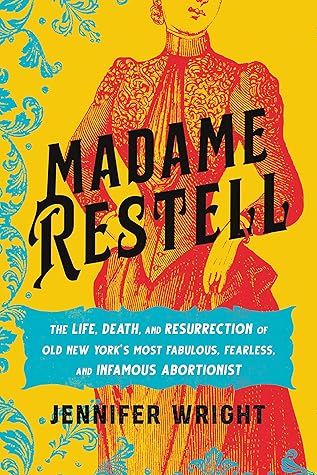

Madame Restell faced a number of obstacles on her route to respectability. For starters, she read too much, dressed too well, and had far too much of a sense of humor. She also performed abortions, which made even attempting it borderline insane.

As the number of immigrants increased—not only from Ireland but, to a lesser extent, from Germany, in the middle of the nineteenth century—so did native-born New Yorkers’ prejudice against them. Many saw them as poor people of low moral standing who would bring corrupt influences to New York. Most of the immigrants were poor, though their poverty resulted in part from the willingness of native-born Americans to exploit them.

The result of this bubbling xenophobic turmoil was the rise of the Know-Nothing movement, which was more formally known as the American Party. The Know

Nothings were defined by their opposition to immigrants and calls for a return to traditional American values—such as reading the Bible in school, banning all Catholics from office, immediate deportation of all foreign beggars or thieves, and a twenty-one-year naturalization period for immigrants.

“How long is it, Mr. Know-Nothing, since your father came to this country?… He may have been the oldest inhabitant or he may have been the newest, but as he followed after the Indians, he was himself a foreigner. And pray, friend, what right have you, a foreigner’s descendent, to persecute those who, like him, choose to settle among us? You ought to be ashamed of yourself!”25

While many intellectuals and progressives at the time might have despised Know Nothings, their numbers continued to swell, as did their influence. In New York City, it reached an apex with the death of William Poole, aka “Butcher Bill,” a leader of the New York Know Nothings. Bill, who was best known for being the leader of the Bowery Boys gang, also wrote anti-immigrant poetry, featuring lines such as “Let not our country in their hands be given / and thus betray the trust received from heaven.”

So doctors in the 1850s couldn’t say they were better than, or even equal to, midwives in terms of their skills. The fact that male doctors thought they should take over a field in which midwives excelled and of which they had virtually no knowledge would seem bizarre were there not so much money to be made. As such, it seems sadly predictable.

Horatio Storer, a twenty-seven-year-old Harvard-educated gynecologist who joined the AMA the year prior. Storer was fervently antiabortion. He believed that as soon as a woman was impregnated, the embryo was an independent person.

The notion of a separate and independent existence was more than Storer would admit to women, over whom he felt justified in exerting enormous control. His idea that the fetus was a person and the woman’s uterus a mere resting spot for it is one still employed by antiabortion advocates today, complete with pictures of a fetus floating in a pink cloud blissfully devoid of context. The fact that the fetus is so entwined with a woman’s body that birthing it regularly caused her to die was not something Storer was overly concerned with,

Storer “seems to have thrown out of consideration the life of the mother.”22 It’s little wonder these fetuses Storer and his cohorts referred to were always described as “the potential male” or “the future young man.”

Though the members of the AMA may not have shared all Storer’s convictions, many of the doctors were doubtless aware that discrediting midwives and insisting that men were the only ones qualified to oversee women’s reproductive health would open up a new and welcome source of income for them.

Storer, in what can only be considered a really big swing to the fences, claimed that even thinking about having an abortion could kill you. “The thought of the crime,” he explained, “coming upon the mind at a time when the physical system is weak and prostrated is sufficient to occasion death.” As if the threat of death wasn’t absurd enough, Storer also wanted women to know that just thinking about it was “undoubtedly able, where not affecting life, to produce insanity.”

The mental health concerns here are particularly interesting. The psychological ramifications of abortion have been studied over time, especially because antiabortionists are still apt to argue that the operation negatively impacts women’s mental health. However, modern-day studies have not found this to be true.

In June 2022 the American Psychological Institute reported that, “More than 50 years of international psychological research shows that having an abortion is not linked to mental health problems.”

What does cause modern women psychological distress—and we might imagine this also applied to women of the past—is being denied access to the care they need. According to a 2016 study, women who are denied an abortion are more likely to report “anxiety symptoms, lower self-esteem, and lower life satisfaction”

Long before this study, the same thought played a role in the US Supreme Court’s 1973 opinion on Roe v. Wade, which stated that “maternity, or additional offspring, may force upon the woman a distressful life and future. Psychological harm may be imminent.”31

Vanity and selfishness. Aborted fetuses, the 1860s antiabortionist crusader J. T. Cook claimed, “premature martyrs to woman’s vanity, woman’s selfishness, and woman’s inhumanity, have gone up to the great white throne with no earthly record of their sacrifice, save the painted, fleeting and fading beauty of vain and fashionable mothers!”38 Storer agreed, opining that, sadly, women who had abortions were “under that strange and masterful thralldom of fashion.”

There’s little evidence to suggest that this is the impetus that men through the ages have imagined. The frequent claim that vanity is the main reason for having an abortion is little more than a tactic to make people who seek out abortions seem frivolous. It is far, far easier to say that women get abortions because they’re irresponsible and self-involved than to address (and perhaps try to remedy) the social causes that, for many women, necessitate abortion. A 2004

But while Madame Restell’s patients in the early 1800s had often been seen as helpless, virginal victims of their male seducers, now antiabortion doctors painted women seeking abortions as rich, villainous socialites. Such theoretical women were far less popular and easier to discredit than the women who actually sought abortions.

The antiabortionists were primarily concerned that when women had more opportunity to socialize, they had more opportunity to misbehave.

In doing so, they

might even become eager to vote, or elope, or wish to enter a profession, or otherwise take on identities other than that of the obedient wife and mother whom some men, such as Storer, preferred.

Incidentally, the cure Storer devised for “female insanity”? Removing women’s ovaries.

“doctors had performed an estimated 150,000 ovariotomies on American women under the guise of protecting their emotional stability and mental health.”47 Without her ovaries, a woman would be unable to have children at all. Men like Storer would be able to make such a decision for her.

Women, physicians seemed to concur, simply could not be trusted with their own bodies, let alone other women’s bodies.

Storer sighed. “In very many instances, from our own experience, has a lady of acknowledged respectability, who had herself suffered abortion, induced it upon several of her friends: thus perhaps endeavoring to persuade an

uneasy conscience, that, by making an act common, it becomes right.”51 Abortions have been considered many things over the centuries, but rarely have they been dubbed a fun bonding activity.

Madame Restell often thought she knew better than her patients. But she did not harbor the illusion that they should be content to be merely kindly nests for future generations, regardless of their circumstances. Nor did she see her patients as deranged lunatics, or shameless narcissists. In this regard, she had a considerable edge over the male physicians of the period.

And so, while the rest of the country pinched pennies, Madame Restell bought the land across from what would be St. Patrick’s Cathedral for a total of $36,500 ($1,160,402 today). Spending a million dollars on a plot of undeveloped land in a largely unpopulated part of town to snub someone was absolutely her style.

“American religion… became one of the Civil War’s major casualties.”

The decades to come would see some of the city’s most memorable fetes. One gala, hosted by Mrs. Stuyvesant Fish, the wife of a railroad tycoon, was given in honor of Prince del Drago of Corsica—who turned out to be a monkey.

course, she could not vote. In 1867, an argument against giving women the vote in papers as far away as Ohio was precisely that “Madam Restell and all the New York prostitutes would go to the polls.”17

Outside the medical profession, some people suggested reducing the number of abortions by treating unwed mothers better, noting, “Of course we can save the lives of a great many illegitimate children by destroying the sense of shame which attaches to the bearing of an illegitimate child.”

The consequences they were bringing upon the country by not having enough white Protestant babies. Historically, people who have treated minorities abominably have hated the idea of becoming a minority themselves. There was much emphasis on the fact that white women having abortions were undermining America as a whole, as “the Anglo-American race is actually dying out.”

It’s unclear what exactly Comstock was thinking about when he masturbated. Most of the erotic prints of the era consist of bejeweled naked women lying on sofas. They don’t really constitute “a horror that no pen can describe,” a description that feels more applicable to, for instance, Cthulhu.

If you were wondering whether Anthony Comstock was still ridiculed for being a dweeb who found everything terrifying in its lewdness, the answer is yes, of course he was. The humor magazine Puck published one of the better-known cartoons about him, featuring a woman exclaiming, “O, dear me, what shall I do? My shoestring has come untied, and there’s that dreadful Anthony Comstock just behind me!”23 A particularly cheeky piece by Robert Minor depicts Comstock dragging a woman before a judge and exclaiming, “Your honor, this woman gave birth to a naked child!”

The mockery of male intellectuals and artists was nothing compared to the support he gained, financial and otherwise, from people who longed for a more religiously conservative version of the United States. He was dangerous in the manner of all fanatics who believe in blotting out everything that “corrupts the minds and morals of our women and children” without ever consulting women, children, or anyone else whose lives might be altered by their policies.25 25

If you couldn’t even read a description of abortive medicine at a trial about abortion, it truly was Comstock’s world now.

As for her business, Rev. McCarthy felt that, in performing abortions, she was not doing anything most doctors didn’t. He personally knew others who performed abortions and noticed that “in high social circles [it was] advocated as a proper method for evading the duties and anxieties of maternity.” Given that abortion was seen as acceptable and accessible for the wealthy, he declared, “The fraud and falsehood by which she was made amenable to a law that is universally violated by the medical profession of this city cannot be too strongly condemned.”

Much of America agreed that Comstock had overstepped when it came to attacking Madame Restell and others he deemed sinful. By October, a judge found that some of the people Comstock prosecuted were legally innocent, as they’d been “induced by a sort of constable [Comstock himself].”

Comstock and his cronies were not in the least troubled by the criticism directed toward them. After all, Madame Restell was not the first person Comstock had driven to suicide; he bragged, in a very morbid flex, that at least fifteen people had killed themselves because of contact with him. For the time being, he was pleased with himself.

Many people wished to remind women that their place was not in the world of business, nor was it campaigning for the vote. Madame Restell was proof that women who did business were evil. Instead, a woman’s place should always be at home, breeding and tending to children.

An 1898 estimate by the Michigan Board of Health found that, in spite of Comstock’s efforts, one-third of the pregnancies in the state were terminated via abortion.

A Stanford University study from 1921 estimated that one in every 1.7 to 2.3 pregnancies ended in abortion. Banning abortion did not stop the procedure and, in some cases, it seems to have increased the rate at which women had them.

Comstock’s laws forbade any discussion of family planning, meaning that women could not even have conversations with their doctors about the options available to them. Sanger saw the patient again the following year as she gave birth to her fourth child. Tragically, the woman died as a result of this childbirth, just as the doctor had predicted.