More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

January 1 - January 27, 2024

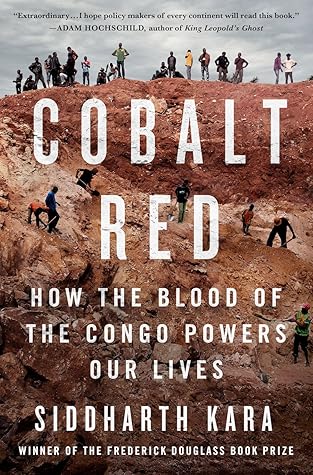

The harsh realities of cobalt mining in the Congo are an inconvenience to every stakeholder in the chain. No company wants to concede that the rechargeable batteries used to power smartphones, tablets, laptops, and electric vehicles contain cobalt mined by peasants and children in hazardous conditions.

In all my time in the Congo, I never saw or heard of any activities linked to either of these coalitions, let alone anything that resembled corporate commitments to international human rights standards, third-party audits, or zero-tolerance policies on forced and child labor. On the contrary, across twenty-one years of research into slavery and child labor, I have never seen more extreme predation for profit than I witnessed at the bottom of global cobalt supply chains.

Throughout much of history, mining operations relied on the exploitation of slaves and poor laborers to excavate ore from dirt. The downtrodden were forced to dig in hazardous conditions with little regard to their safety and for little to no compensation. Today, these laborers are assigned the quaint term artisanal miners, and they toil in a shadowy substrate of the global mining industry called artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM). Do not be fooled by the word artisanal into thinking that ASM involves pleasant mining activities conducted by skilled artisans. Artisanal miners use

...more

could have altered the course of history in the Congo and across Africa. In short order, Belgium, the United Nations, the United States, and the neocolonial interests they represented rejected Lumumba’s vision, conspired to assassinate him, and propped up a violent dictator, Joseph Mobutu, in his place. For thirty-two years, Mobutu supported the Western agenda, kept Katanga’s minerals flowing in their direction, and enriched himself just as egregiously as the colonizers who came before him.

Consider the first sentence, because this is the important one. If the OECD and its constituents concede that 70 percent of 72 percent of the world’s supply of cobalt “has some touch” with child labor, that would imply that half of the cobalt in the world was touched by child labor in the Congo. This fact alone indicted a preponderance of the global supply chain of cobalt, yet child labor was far from the only problem in the Congo’s artisanal mining sector. How much of the Congo’s cobalt was “touched” by the hundreds of thousands of Congolese people suffering the consequences of toxic exposure

...more

They stated that almost all the production at the four sites was artisanal. They also asserted that SAEMAPE officials were present at the MIKAS mines and that they tallied the weight of each day’s production, which determined MIKAS’s royalty payment to the Congolese government. If true, it would mean that the government agency tasked with monitoring artisanal miners and protecting their interests was part of the system of illegally utilizing artisanal miners on industrial sites. I would encounter similar reports at other industrial sites farther along the road to Kolwezi.

Lumumba ended his incendiary speech with a declaration to the Belgian king: “Nous ne sommes plus vos singes”—“We are no longer your monkeys.”4

Eleven days after independence, the Belgians executed a brazen plan to keep control of what mattered most in the Congo—the minerals of Katanga. They backed Moise Tshombe in announcing that Katanga Province had seceded from the Congo. UMHK provided crucial financial support to Tshombe’s administration, and Belgian troops expelled the Congolese army from Katanga. With surgical precision, the Belgians had severed Katanga Province like a hand from the body of the nation, and with it, 70 percent of the government’s income. The country was crippled before it ever had a chance.

The UN responded with the largest ground operation since its creation to help stabilize the nation, but the forces were not authorized to expel Belgian troops. Lumumba turned instead to the Soviet Union for help. The possibility that the Congo, and especially Katanga, might come under Soviet influence put the United States, the United Nations, and Belgium into overdrive to dispatch Lumumba. On August 18, 1960, President Dwight Eisenhower met with his national security council to discuss the situation in the Congo and proclaimed that the U.S. had to “get rid of this guy.”5 The CIA hatched a

...more

The incoming Kennedy administration was worried that Lumumba might return to power and persuaded Belgium to send Lumumba to their stronghold in Élisabethville to be executed.

Mobutu remained in power for decades, despite overt corruption, by embracing the U.S. cause against communism, which brought him the unwavering support of Presidents Nixon, Bush, Reagan, and Clinton. Katanga’s minerals flowed to the West, and the proceeds flowed into Mobutu’s bank accounts. However, that which Katanga gives, it can also take away.

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, Mobutu’s value to the West collapsed with it. A genocide in neighboring Rwanda proved to be the catalyst for his final downfall.

The degeneration of Zaire under Mobutu made it possible for its comparatively diminutive neighbors to contemplate an invasion. The head of the Rwandan army and current president of Rwanda, Paul Kagame, seized the opportunity. Kagame orchestrated an attack on the Kivus in conjunction with Uganda, using a Katangan front man and longtime opponent of Mobutu—Laurent-Désiré Kabila.

Like Mobutu and Leopold before him, Laurent Kabila ran the Congo as a kleptocratic system of personal enrichment.

What followed on August 2, 1998, and for years thereafter became known as “Africa’s Great War,” an internecine explosion of violence involving nine African nations and thirty militias that laid waste to the DRC and resulted in the death of at least five million Congolese civilians.

What else could the purpose of this kind of remote night marketplace be, other than to launder artisanally mined cobalt into the formal supply chain completely out of view, and certainly beyond the scope of any tracing or auditing of cobalt supply chains that were purportedly taking place? Can any company at the top of the chain legitimately suggest that the cobalt in their devices or cars did not pass through a village marketplace like this?