More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

January 10 - February 9, 2024

Nyama tembo kula hawezi kumaliza. (“You never finish eating the meat of an elephant.”) —Congolese saying

Foreign powers have penetrated every inch of this nation to extract its rich supplies of ivory, palm oil, diamonds, timber, rubber … and to make slaves of its people. Few nations are blessed with a more diverse abundance of resource riches than the Congo. No country in the world has been more severely exploited.

The ongoing exploitation of the poorest people of the Congo by the rich and powerful invalidates the purported moral foundation of contemporary civilization and drags humanity back to a time when the people of Africa were valued only by their replacement cost.

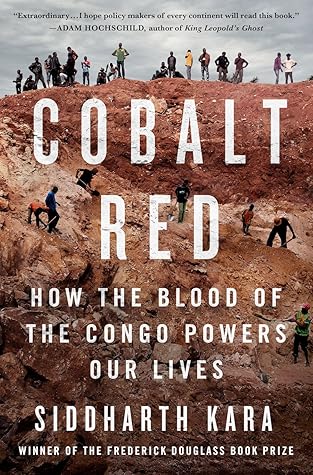

The harsh realities of cobalt mining in the Congo are an inconvenience to every stakeholder in the chain. No company wants to concede that the rechargeable batteries used to power smartphones, tablets, laptops, and electric vehicles contain cobalt mined by peasants and children in hazardous conditions.

The titanic companies that sell products containing Congolese cobalt are worth trillions, yet the people who dig their cobalt out of the ground eke out a base existence characterized by extreme poverty and immense suffering.

Our daily lives are powered by a human and environmental catastrophe in the Congo.

Today, these laborers are assigned the quaint term artisanal miners, and they toil in a shadowy substrate of the global mining industry called artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM). Do not be fooled by the word artisanal into thinking that ASM involves pleasant mining activities conducted by skilled artisans. Artisanal miners use rudimentary tools and work in hazardous conditions to extract dozens of minerals and precious stones in more than eighty countries across the global south.

The journey into the mining provinces was at times a jarring time warp. The most advanced consumer electronic devices and electric vehicles in the world rely on a substance that is excavated by the blistered hands of peasants using picks, shovels, and rebar. Labor is valued by the penny, life hardly at all.

COVID-19 spread rapidly in the artisanal mines of the Congo, where mask wearing and social distancing were impossible. The sick and dead infected by the disease were never counted, adding an unknown number to the industry’s bleak tally.

The Congolese military and other security forces are omnipresent in mining areas, making access to mining sites dangerous and at times impossible. Perceived troublemakers can be arrested, tortured, or worse.

It was a bold, anti-colonial vision that could have altered the course of history in the Congo and across Africa. In short order, Belgium, the United Nations, the United States, and the neocolonial interests they represented rejected Lumumba’s vision, conspired to assassinate him, and propped up a violent dictator, Joseph Mobutu, in his place.

Most people do not know what is happening in the cobalt mines of the Congo, because the realities are hidden behind numerous layers of multinational supply chains that serve to erode accountability. By the time one traces the chain from the child slogging in the cobalt mine to the rechargeable gadgets and cars sold to consumers around the world, the links have been misdirected beyond recognition, like a con man running a shell game.

There is no known deposit of cobalt-containing ore anywhere in the world that is larger, more accessible, and higher grade than the cobalt under Kolwezi.

At no point in their history have the Congolese people benefited in any meaningful way from the monetization of their country’s resources. Rather, they have often served as a slave labor force for the extraction of those resources at minimum cost and maximum suffering.

The battery packs in electric vehicles require up to ten kilograms of refined cobalt each, more than one thousand times the amount required for a smartphone battery. As a result, demand for cobalt is expected to grow by almost 500 percent from 2018 to 2050,3 and there is no known place on earth to find that amount of cobalt other than the DRC.

In fact, no one seems to accept responsibility at all for the negative consequences of cobalt mining in the Congo—not the Congolese government, not foreign mining companies, not battery manufacturers, and certainly not mega-cap tech and car companies.

As of 2022, there is no such thing as a clean supply chain of cobalt from the Congo. All cobalt sourced from the DRC is tainted by various degrees of abuse, including slavery, child labor, forced labor, debt bondage, human trafficking, hazardous and toxic working conditions, pathetic wages, injury and death, and incalculable environmental harm.

The DRC ranks 175 out of 189 on the United Nations Human Development Index. More than three-fourths of the population live below the poverty line, one-third suffer from food insecurity, life expectancy is only 60.7 years, child mortality ranks eleventh worst in the world, access to clean drinking water is only 26 percent, and electrification is only 9 percent.

Education is supposed to be funded by the state until eighteen years of age, but schools and teachers are under-supported and forced to charge fees of five or six dollars per month to cover expenses, a sum that millions of people in the DRC cannot afford. Consequently, countless children are compelled to work to support their families, especially in the mining provinces.

EV sales could end up being even greater, as twenty-four nations pledged at COP26 to eliminate the sale of gas-powered vehicles entirely by 2040. Millions of tons of cobalt will be needed, which will continue to push hundreds of thousands of Congolese women, men, and children into hazardous pits and tunnels to help meet demand.

The governor-general of the Belgian Congo, Pierre Ryckmans, declared in June 1940: “The Belgian Congo, in the present war, is the most important asset of Belgium. It is entirely at the service of the Allies, and through them of the motherland. If she needs men, it will give them; if she needs work, it will work for her.”6 Tens of thousands of Congolese people were worked to the bone in copper mines and sent to the war to die for the benefit of Belgium and its European allies.

No one knows how many people live in Lubumbashi—or in any other Congolese city, for that matter—because the last census conducted by the government was in 1984.

Displacement of the native population due to mine expansion is a major crisis in the mining provinces. As the living conditions of displaced people worsen, their desperation increases, and that desperation is precisely what drives thousands of local inhabitants to scrounge for cobalt in hazardous conditions on the land they once occupied.

Makaza said he lived in constant fear of being displaced the next time the mine expanded, or when some new mine was built. “Eventually, there will be no place left in Congo for Congolese people,” he said.

Let me tell you the most important thing that no one is discussing. The mineral reserves in Congo will last another forty years, maybe fifty? During that time, the population of Congo will double. If our resources are sold to foreigners for the benefit of the political elite, instead of investing in education and development for our people, in two generations, we will have two hundred million people who are poor, uneducated, and have nothing left of value. This is what is happening, and if it does not stop, it will be a disaster.

The foundation for China’s dominance in Africa was established in 2000 when President Jiang Zemin proposed the creation of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation to facilitate Chinese investments in African countries. The relationship was billed as a win-win: the Chinese would build much-needed roads, dams, airports, bridges, mobile networks, and power plants across Africa, and in exchange, China would secure access to vital resources to support its growing economy.

Crucially, the SICOMINES deal is exempt from taxes until infrastructure and mining loans are fully repaid, which means that the DRC will not receive meaningful income from the deal for many years to come.

I asked if there were children digging in the forest. “Yes, of course,” Philippe replied. “What else will they do? There are no schools in the villages. Each member of the family must earn for the collective to survive.”

Cobalt is toxic to touch and breathe, but that is not the biggest worry that the artisanal miners have. The ore often contains traces of radioactive uranium.

They were not kin to each other but worked in a group to keep safe. Sexual assault by male artisanal miners, négociants, and soldiers was common in mining areas. The women said they all knew someone who had been shoved into a pit and attacked, the likely cause of at least some of the babies strapped to teenage backs.

Priscille said that she had no family and lived in a small hut on her own. Her husband used to work at this site with her, but he died a year ago from a respiratory illness. They tried to have children, but she miscarried twice. “I thank God for taking my babies,” she said. “Here it is better not to be born.”

Philippe told me that women were always paid less than men for the same sack of cobalt.

Beyond the horizon, beyond all reason and morality, people from another world awoke and checked their smartphones. None of the artisanal miners I met in Kipushi had ever even seen one.

There was nothing to stop mining companies from going to the artisanal sites themselves and directly paying the women, men, and children who dug their cobalt—aside from the negative optics associated with having direct links to hazardous, penny-wage artisanal mining areas teeming with children.

In the studies we conducted, the artisanal miners have more than forty times the amount of cobalt in their urine as the control groups. They also have five times the level of lead and four times the level of uranium. Even the inhabitants living close to the mining areas who do not work as artisanal miners have very high concentrations of trace metals in their systems, including cobalt, copper, zinc, lead, cadmium, germanium, nickel, vanadium, chromium, and uranium.

“Even if children do not work in the mines, indirect exposure to heavy metals from their parents is worse for them than direct exposure for the adults. This is because a child’s body cannot remove heavy metals as well as adults can.”

Samples of dust taken inside homes throughout the Copper Belt had an average of 170 micrograms of lead per square foot. Germain explained that the lead dust probably came from the clothes of mine workers, as well as metal processing at some of the large mines. By way of comparison, the Environmental Protection Agency in the United States recommends a maximum safe limit of 40 micrograms of lead per square foot inside homes.

“There is no training of doctors to diagnose and treat health ailments arising from contamination by heavy metals,” he said. Many villages and artisanal mining communities did not have basic medical clinics available to them to treat simple ailments, let alone seizures or cancers.

The mining companies do not control the runoff of effluents from their processing operations. They do not clean up when they have chemical spills. Toxic dust and gases from mining plants and diesel equipment spreads for many kilometers and are inhaled by the local population. The mining companies have polluted the entire region. All the crops, animals, and fish stocks are contaminated.

“Before getting a concession, the mining companies must submit a plan on waste management to the government. Of course, they do not adhere to their plans. But the government is not sending people to monitor their activities either.”

Therein lies the great tragedy of the Congo’s mining provinces—no one up the chain considers themselves responsible for the artisanal miners, even though they all profit from them.

We are rarely asked, if ever, to confront the untold suffering that has been endured by Africa.

Imagine for a moment the toll taken on a person, a family, a people, a continent across centuries of the slave trade, followed by a century of colonization. Empires were built and generations of wealth were amassed across the Western world in this manner. Perhaps that is the most enduring contrast of all between our world and theirs—our generally safe and satisfied nations can scarcely function without forcing great violence upon the people of Africa.

I met Hu at the Royal Casino, one of the private Chinese clubs in Lubumbashi. We sat poolside in the open air. Chinese men drank and smoked as heavy-beat club music thumped through the speakers. Congolese people were not allowed inside the club, except when the strippers arrived around 9:00 p.m.

Indians have a long history on the continent dating back to the 1840s, when the British began shipping them to Africa to work as debt bondage slaves on railroads and plantations.

In Africa, a hierarchy was soon established—Africans at the bottom, Indians and Arabs above them, and Europeans at the top. Skin tone dictated the hierarchy back then, and it still does today—simply swap out the Europeans with the Chinese.

Shinkolobwe provided roughly 75 percent of the uranium that was used for the bombs dropped from the Enola Gay on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945.1 Although Shinkolobwe has been nonoperational for decades, rumors persist that rogue army officials and organized criminals excavate uranium and sell it on the black market to the likes of Iran, North Korea, and Pakistan.

The boys expelled metallic coughs as they spoke. They complained of itching and burning skin on their legs, as well as chronic pain in their backs and necks. They had been breaking and washing stones in the village for as long as they could remember and had never attended a day of school.

“Look at my grandchildren. This is what cobalt has done to Congolese children. They have no more future.”

Arthur explained that by “sponsor,” Kiyonge meant commandos or négociants. They were known to traffic children from other villages and even neighboring provinces into artisanal digging sites such as Kiyonge’s village to boost production.