More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

December 31, 2024 - January 8, 2025

push for renewable sources of energy beginning in 2010 led to an electric vehicle renaissance.

Paris Agreement in 2015, in which 195 nations agreed to a shared goal of keeping the increase in global average temperatures to less than 2°C from preindustrial levels. To achieve this goal, CO2 emissions must be reduced by at least 40 percent below 2015 levels by 2040. Since about one-fourth of CO2 emissions are created by vehicles with internal com...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

8 EV sales could end up being even greater, as twenty-four nations pledged at COP26 to eliminate the sale of gas-powered vehicles entirely by 2040. Millions of tons of cobalt will be needed, which will continue to push hundreds of thousands of Congolese women, men, and children into hazardous pits and tunnels to help meet demand.

To achieve mass adoption of electric vehicles at the levels projected will require that EV batteries become cheaper and are able to achieve longer ranges between charges.

hour, the production cost of lithium-ion battery packs has fallen 89 percent from $1,200/kWh in 2010 to $132/kWh in 2021.

To increase range, batteries require higher energy densities, and only lithium-ion chemistries using cobalt cathodes are currently able to deliver maximum energy density while maintaining thermal stability.

Batteries provide portable sources of electrical energy by rebalancing a chemical imbalance between a cathode (positive electrode) and an anode (negative electrode).

The cathode and anode are separated by a chemical barrier called an electrolyte. When the cathode and anode are connected to a device, this creates a circuit, which results in a chemical reaction that generates positive ions and negative electrons at the anode. An opposite reaction takes place at the cathode.

the positive ions and negative electrons in the anode travel to the cathode, but they take different paths to reach their destinations. The ions flow directly through the electrolyte to the cathode, whereas the electrons flow through the external circuit to the cathode. The electrons are unable to travel through the electrolyte because its che...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

flow of electrons creates the energy that powers the device. As a battery generates electrical power, the chemicals inside it are gradually “used up.” A rechargeable battery, on the other hand, is one that allows a change in the direction of flow of electrons and ions usin...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Lithium-based chemistries became the dominant form for rechargeable batteries because lithium is the lightest metal in the world, which has obvious benefits for consumer technology and electric vehicle applications. Cobalt is used in the cathodes of lithium-ion batteries because it possesses a unique electron configuration that allows the battery to remain stable at higher energy densities throughout repeated charge-discharge cycles. Higher energy density means the battery can hold more charge, which is critical to maximize the driving range of an electric vehicle between charges.

The three primary types of lithium-ion rechargeable batteries used today are lithium cobalt oxide (LCO), lithium nickel manganese cobalt oxide (L-NMC), and lithium nickel cobalt aluminum oxide (L-NCA). Lithium accounts for only 7 percent of the materials used in each type of battery, whereas cobalt can be as high as 60 percent.

LCO batteries provide high energy density, which allows them to store more power per weight of battery. This quality makes them ideal for use in consumer electronic devices such as mobile phones, tablets, and laptops. The tradeoff is that LCO batteries have shorter life spans and deliver a lower amount of power,

L-NMC batteries are used in most electric vehicles, except for Tesla, which uses L-NCA batteries. Since 2015, the trend with these batteries has been to reduce cobalt reliance by moving toward higher ratios of nickel.11 Nickel has lower thermal stability than cobalt, so the higher the ratio of nickel used, the lower the battery’s stability and safety. The limited supply and high cost of cobalt has not gone unnoticed by the EV industry. Battery researchers are working on alternative designs that can minimize or eliminate reliance on cobalt. At present, most cobalt-free alternatives have

...more

Even after battery designers find a way to eliminate cobalt from rechargeable batteries without sacrificing performance or safety, the misery of the Congolese people will not end. There will surely be another prize slumbering in the dirt that will be made valuable by the global economy. Such has been the curse of the Congo for generations. Unspeakable riches have brought the people of the Congo little other than unspeakable pain.

Cobalt mining is the slave farm perfected—the cost of labor has been nullified through the degradation of Africans at the bottom of an economic chain that purports to exonerate all participants of accountability through a shrewd scheme of obfuscation adorned with hypocritical proclamations about the preservation of human rights. It is a system of absolute exploitation for absolute profit. Cobalt mining is the latest in a long history of “enormous and atrocious” lies that have tormented the people of the Congo.

Of all the shameful and infamous expedients whereby man has preyed upon man … this vile thing dares to call itself commerce. —Roger Casement, letter to the Foreign Office, September 6, 1903

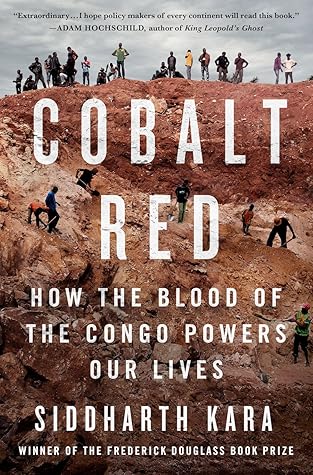

There is a giant open-air copper-cobalt pit mine called Ruashi located next to the airport. “You will fly right over it when you land in Lubumbashi,”

It was an enormous hollowing of the earth consisting of three behemoth pits, each of which was several hundred meters in diameter. Heavy-duty excavators drove along the terraced edges of the craters like little yellow ants. Next to the pits, there was a mineral-processing facility with numerous chemical storage vats and rectangular pools of water. Toxic waste from the processing plant was discarded into a large, square-shaped depository roughly one square kilometer in size. The entire complex was more than ten square kilometers,

The Belgians founded a mining town here called Élisabethville in 1910 to exploit their very first mine in Katanga, Étoile du Congo (“Star of the Congo”), which is just south of Ruashi. Excavations at Ruashi followed in 1919. The original settlement contained white-owned businesses surrounded by tree-lined streets where the Europeans lived. Mine-worker compounds for African laborers were erected in patchwork plots near Étoile and Ruashi. Both mines still operate today,

When the Congo Free State passed in ownership from King Leopold II to the Belgian government, the colony was renamed the Belgian Congo. At independence in 1960, the nation was renamed Republic of Congo. In the early 1970s, Joseph Mobutu commenced an “Africanization” campaign in which all colonial names were replaced with African ones—Élisabethville became Lubumbashi, Léopoldville became Kinshasa, Katanga became Shaba, and Republic of Congo became Zaire. In 1997, Laurent Kabila invaded the country, took control from Mobutu, and renamed it to the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Being a

...more

Native Katangans had been mining copper from the region’s copious deposits long before Europeans arrived. Katangan copper first made its way to Europe via Portuguese slave traders as early as the sixteenth century. In 1859, the Scottish explorer David Livingstone arrived on a trek from South Africa into Katanga and noted large pieces of copper “in the shape of a St. Andrew’s cross” that were used as a form of payment.

warlord named Mwenda Msiri Ngelengwa Shitambi. Msiri traded copper for firearms with Europeans, amassing an imposing military force. He had a reputation for violence and was infamous for his collection of gleaming white human skulls,

about natives who melted malachite to produce large copper ingots in the shape of a capital I, some of which weighed more than fifty kilograms.

large copper ingots and the sale of slaves to Msiri in exchange for Katangan copper.

The malachite from which the copper is extracted is found in large quantities on the tops of certain bare, rugged hills. In their search for it, the natives dig little round shafts seldom deeper than 15 or 20 feet. They have no lateral workings, but when one shaft becomes too deep for them, they leave it and open another.

1886 caught the attention of British imperialist Cecil Rhodes, founder of the prestigious Rhodes Scholarship. Rhodes ventured north from his eponymous Rhodesia (Zambia) into Katanga to meet with Msiri in the hopes of signing a treaty that would place Katanga under British dominion. Msiri sent Rhodes packing without a treaty.

Hearing of Rhodes’s efforts in Katanga, King Leopold, who had just secured his Congo Free State in 1885, immediately dispatched three teams to secure a treaty with Msiri. A campaign led by the Belgian explorer Alexandre Delcommune arrived first on October 6, 1891, and met with Msiri. Like Rhodes, Delcommune was rebuffed. A second campaign of Zanzibari mercenaries led by the British turncoat William Grant Stairs arrived on December 20, 1891. Stairs met with Msiri, but the next day, Msiri left for a neighboring village. Stairs sent his two most trusted men to reason with Msiri, but after three

...more

Cornet was the first European to document the extensive copper deposits in what would turn out to be the Central African Copper Belt. He even had a local stone named after him, cornetite.

It will be utterly impossible to exhaust your bodies of oxidized ores during this century … The quantity of copper you can thus produce is entirely a question of demand—the mines can supply any amount. You can make more copper and make it much cheaper than any mines now working. I believe your mines will be the source of the world’s future supply of copper.

In securing Katanga, Leopold had literally struck pay dirt, and the Belgians moved quickly into exploitation mode. On October 18, 1906, the Belgians created Union Minière du Haut-Katanga (UMHK) to exploit the copper deposits across the Katanga region. The Belgian state granted UMHK extensive parastatal powers, including the ability to build and manage urban centers with African laborers to be used in the exploitation of mining assets.

Katanga’s native population proved insufficient to meet the labor requirements of UMHK’s fast-growing mining operations, so the company recruited thousands of workers and purchased slaves to work in the mines. African laborers were crammed into ramshackle barracks and exploited in a forced labor regime reminiscent of some of the harshest systems of African slavery. Profits soared, especially after the start of World War I, during which time millions of bullets fired by British and American forces were made with Katangan copper.5

During World War II, Katanga again proved indispensable to the Allied war effort, providing gold, tin, tungsten, cobalt, and more than eight hundred thousand tons of copper for the manufacture of ordnance.

Tens of thousands of Congolese people were worked to the bone in copper mines and sent to the war to die for the benefit of Belgium and its European allies.

At independence on June 30, 1960, the formal economy of the Congo was based almost entirely on the extraction of minerals from Katanga Province. Most of this extraction was controlled by UMHK, which had no interest in parting with its highly profitable mining operations. UMHK and the Belgian military backed a Katangan politician, Moise Tshombe, in declaring Katanga’s secession from the Republic of Congo eleven days after the nation’s independence.

The luggage room is manned by a third batch of soldiers who rummage through the suitcases of foreign passengers for items that might indicate the person has an interest in prying into matters they should not, like the mining sector.

There are also soldiers at checkpoints leaving the airport and all around Lubumbashi that make random searches and ask to verify the travel paperwork of foreign visitors. The process repeats itself at every one of the five péage (toll) checkpoints on the road between Lubumbashi and Kolwezi. Even with pristine paperwork, harassment by soldiers at the checkpoints is common.

No one knows how many people live in Lubumbashi—or in any other Congolese city, for that matter—because the last census conducted by the government was in 1984. Local estimates put Lubumbashi’s population at more than two million, making it the second-largest city in the country behind Kinshasa. The main arterial road of Lubumbashi is called 30 June 1960 Street, the day of Congolese independence.

Most adults dress in a vibrant style called liputa, an explosion of rich colors and bold motifs. On more formal occasions, women wear the resplendent pagne, a three-piece outfit of matching skirt, blouse, and headscarf drenched in brilliant hues and eye-catching designs.

Half of the Congolese population is Catholic, and about one-fourth of the country is Protestant.

There is a sizable Indian population in the Congo,

Although Lubumbashi is the administrative capital of the DRC’s mining sector, there is very little mining that takes place in the city outside of Ruashi and Étoile, which combined to produce about 8,500 tons of cobalt in 2021.7 Both mines passed from UMHK to Gécamines on the first day of 1967 after Mobutu nationalized the country’s mining sector. Production under Gécamines was inconsistent and eventually abandoned after the company’s financial collapse in the early 1990s. The rights to Ruashi were acquired in 2012 by the state-owned Chinese mining giant Jinchuan Group. The rights to Étoile

...more

Étoile is noteworthy not only because it was the first mine the Belgians started exploiting in the Congo in 1911 but also because it was the first industrial mine in the Congo at which artisanal miners were formally encouraged to work, beginning in the late 1990s. Soon after seizing the country in a military coup in 1997, Laurent Kabila promoted artisanal mining at Étoile to generate desperately needed revenue for his fledgling government. Although local villagers were promised improved incomes and living conditions, their labor was instead used to restart production at Étoile for paltry

...more

Makaza said that he typically produced between forty and fifty kilograms of heterogenite each day by digging in the large pits or along the pit walls, for which he was paid 2,000–2,500 Congolese francs (CF) (about $1.10–$1.40).

who exactly paid him, and Makaza said, “The men from CHEMAF.”

Water came from narrow wells ringed at the top by old jeep tires. The villagers subsisted on vegetables grown in a few sallow fields. The closest medical clinic was five kilometers away, and the closest school was seven.

Makaza’s family used to live in a nicer village much closer to basic amenities, but that village was demolished during one of Étoile’s expansions. Like most of the industrial mines in the Congo, Étoile’s concession has grown across the years, displacing thousands of local inhabitants. Displacement of the native population due to mine expansion is a major crisis in the mining provinces. As the living conditions of displaced people worsen, their desperation increases, and that desperation is precisely what drives thousands of local inhabitants to scrounge for cobalt in hazardous conditions on

...more

The militia, called Mai-Mai Bakata Katanga, was an especially violent group that occasionally seized control of villages and mineral territory with the purported mission of seceding Katanga Province from the country.

Most of the Congo’s major artisanal mining sites are located far to the west of Lubumbashi between the cities of Likasi and Kolwezi.

of ugali, a traditional Congolese dish that consists of a boiled ball of maize flour served with stew.