More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

July 9 - July 14, 2024

In all my time in the Congo, I never saw or heard of any activities linked to either of these coalitions, let alone anything that resembled corporate commitments to international human rights standards, third-party audits, or zero-tolerance policies on forced and child labor. On the contrary, across twenty-one years of research into slavery and child labor, I have never seen more extreme predation for profit than I witnessed at the bottom of global cobalt supply chains.

yet the people who dig their cobalt out of the ground eke out a base existence characterized by extreme poverty and immense suffering. They exist at the edge of human life in an environment that is treated like a toxic dumping ground by foreign mining companies.

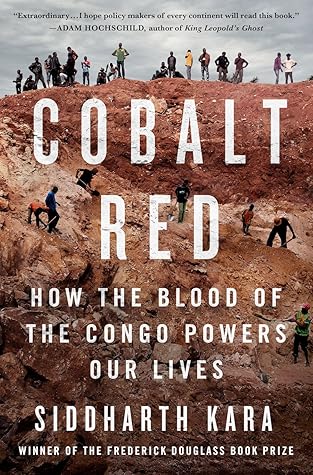

Our daily lives are powered by a human and environmental catastrophe in the Congo.

Joseph Conrad immortalized the evil of Leopold’s Congo Free State in Heart of Darkness (1899) with four words—“The horror! The horror!” He subsequently described the Congo Free State as the “vilest scramble for loot that ever disfigured the history of human conscience” and a land in which “ruthless, systematic cruelty towards the blacks is the basis of administration.”

Furthermore, the inevitable outcome of a lawless scramble for cobalt in an impoverished and war-torn country can only be the complete dehumanization of the people exploited at the bottom of the chain.

Although most people have never heard of Kolwezi, billions of people could not conduct their daily lives without this city. The batteries in almost every smartphone, tablet, laptop, and electric vehicle made today cannot recharge without Kolwezi.

At no point in their history have the Congolese people benefited in any meaningful way from the monetization of their country’s resources.

Apple, Samsung, Google, Microsoft, Dell, LTC, Huawei, Tesla, Ford, General Motors, BMW, and Daimler-Chrysler are just some of the companies that buy some, most, or all their cobalt from the DRC, by way of battery manufacturers and cobalt refiners based in China, Japan, South Korea, Finland, and Belgium. None of these companies claims to tolerate the hostile conditions under which cobalt is mined in the Congo, but neither they nor anyone else are undertaking sufficient efforts to ameliorate these conditions. In fact, no one seems to accept responsibility at all for the negative consequences of

...more

Although the copious mineral riches of Katanga could easily fund numerous programs to improve child education, alleviate child mortality, upgrade sanitation and public health, and expand electrification for the Congolese people, most of the mineral wealth flows out of the country.

Despite being home to trillions of dollars in untapped mineral deposits, the DRC’s entire national budget in 2021 was a scant $7.2 billion, similar to the state of Idaho, which has one-fiftieth the population.

The DRC ranks 175 out of 189 on the United Nations Human Development Index. More than three-fourths of the population live below the poverty line, one-third suffer from food insecurity, life expectancy is only 60.7 years, child mortality ranks eleventh worst in the world, access to cle...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Despite helping to generate untold riches for major technology and car companies, most artisanal cobalt miners earn paltry incomes between one or two dollars per day.

There is no scrutiny at any depots as to the source or conditions under which the ore being purchased was mined. After the depots purchase ore from négociants or artisanal miners, they sell their supply to industrial mining companies and processing facilities.

Although Congolese law stipulates that mineral depots should be registered and operated only by Congolese nationals, almost all depots in Haut-Katanga and Lualaba Provinces are operated by Chinese buyers.

Cobalt is toxic to touch and breathe, but that is not the biggest worry that the artisanal miners have. The ore often contains traces of radioactive uranium.

Beyond the horizon, beyond all reason and morality, people from another world awoke and checked their smartphones. None of the artisanal miners I met in Kipushi had ever even seen one.

There was nothing to stop mining companies from going to the artisanal sites themselves and directly paying the women, men, and children who dug their cobalt—aside from the negative optics associated with having direct links to hazardous, penny-wage artisanal mining areas teeming with children.

In the studies we conducted, the artisanal miners have more than forty times the amount of cobalt in their urine as the control groups. They also have five times the level of lead and four times the level of uranium. Even the inhabitants living close to the mining areas who do not work as artisanal miners have very high concentrations of trace metals in their systems, including cobalt, copper, zinc, lead, cadmium, germanium, nickel, vanadium, chromium, and uranium.

“Even if children do not work in the mines, indirect exposure to heavy metals from their parents is worse for them than direct exposure for the adults. This is because a child’s body cannot remove heavy metals as well as adults can.”

wildlife such as fish and chickens that he tested also showed very high levels of heavy metals.

The mining companies do not control the runoff of effluents from their processing operations. They do not clean up when they have chemical spills. Toxic dust and gases from mining plants and diesel equipment spreads for many kilometers and are inhaled by the local population. The mining companies have polluted the entire region. All the crops, animals, and fish stocks are contaminated.

Therein lies the great tragedy of the Congo’s mining provinces—no one up the chain considers themselves responsible for the artisanal miners, even though they all profit from them.

The Chinese pay billions to the government, and the politicians close their eyes. Organizations like IDAK and other civil society organizations are allowed to exist only to show they exist.”

Now you can see—never have the people of Congo benefited from the mines of Congo. We only become poorer.

our generally safe and satisfied nations can scarcely function without forcing great violence upon the people of Africa. The catastrophe in the mining provinces of the Congo is the latest chapter in this unholy tale.

This land that is home to the world’s largest reserves of an element crucial to the manufacture of the most dominant form of rechargeable energy in the world still awaits the arrival of electricity.

far removed from any signs of civilization, there was something akin to an ant colony of humans who tunneled, excavated, washed, packed, and fed valuable cobalt up the chain to the companies that produced the world’s rechargeable devices and cars. I never in all my trips to the Congo saw or heard of any of these companies or their downstream suppliers monitoring this part of the supply chain, or any of the countless places like it.

It was no wonder that impoverished families across the Congo’s mining provinces relied on child labor to survive. At times, it felt like cobalt stakeholders up the chain counted on it. Why help build schools or fund proper education for Congolese children living in mining communities, when the children could just dig up cobalt for pennies instead?

“What did that child die for?” he asked. “For one sack of cobalt? Is that what Congolese children are worth?”

foreign mining companies expropriated large swaths of land, displaced villagers, contaminated the environment, offered little to no support to the local population, and left them to eke out a meager existence in dangerous conditions as artisanal miners on the land they once lived on.

One might imagine such a scene millennia ago, perhaps as tens of thousands of oppressed laborers in Egypt excavated thousands of tons of stone to build the great pyramids … but at the bottom of trillion-dollar supply chains during the modern era? This could not be what adherence to international human rights norms or 100 percent participation in third-party audits with cobalt suppliers was supposed to look like.

The Congolese government directly contributed to the crisis by auctioning off massive parcels of land for billions of dollars and passively sitting back to collect concession fees, royalties, and taxes. Very little of these funds were being redistributed for the benefit of the Congolese people.

So long as the political elite were content to continue the tradition of government-as-theft established by their colonial antecedents, the people of the Congo would continue to suffer.

two facts seemed indisputable: 1) the artisanal contribution of total cobalt production in the Congo could easily exceed even the highest estimates of 30 percent, and 2) the massive amount of artisanal production from the Congo had to flow into the formal supply chains of big tech and EV companies. Where else could 180,000 tons per year of cobalt ore possibly go?

Men fished for dinner from the bridge above the river, and women washed clothes along the riverbank as white-breasted cormorants floated by. The people of Mupanja were being contaminated in every possible way.

What is not discussed in the court documents but is accepted as fact by everyone with whom I spoke is that a uranium-smuggling operation between the DRC and North Korea could only have been brokered and authorized by Joseph Kabila and that Kabila handpicked Arran to handle the operation.

Even with only a fraction of the picture, it seemed evident that Tilwezembe was not just a copper-cobalt mine, it was a killing field.

The depravity and indifference unleashed on the children working at Tilwezembe is a direct consequence of a global economic order that preys on the poverty, vulnerability, and devalued humanity of the people who toil at the bottom of global supply chains. Declarations by multinational corporations that the rights and dignity of every worker in their supply chains are protected and preserved seem more disingenuous than ever.

As we parted ways, Augustin had this to say, “Please tell the people in your country, a child in the Congo dies every day so that they can plug in their phones.”

Although no one will ever know how many children are buried at Tilwezembe, this much is certain—as of November 1, 2021, Tilwezembe is a fully functioning mine, and hundreds of children can be seen entering it each and every day.

It would not be a stretch to suggest that much of the EV revolution rests on the weary shoulders of some of the poorest inhabitants of Kolwezi, yet few of them have the benefit of even the most basic amenities of modern life, such as reliable electricity, clean water and sanitation, medical clinics, and schools for children.

“The mama says the lake is poison,” he reported. “She said, ‘It kills the babies inside us. Mosquitoes do not drink the blood of the people who work here.’”

Child labor, subhuman working conditions, toxic and potentially radioactive exposure, wages that rarely exceeded two dollars per day, and an untold rash of injuries were the norm.

Consumer-facing tech and EV companies, mining companies, and other stakeholders in the cobalt chain invariably point their fingers downstream, even at their own subsidiaries, as if doing so somehow severs their responsibility for what is happening in the cobalt mines of the Congo.

Although these companies consistently proclaim their commitments to international human rights norms, the implementation of these commitments seems to be nonexistent in the DRC.

The global economy presses like a dead weight on the artisanal miners, crushing them into the very earth upon which they scrounge.

She said that prostitution and digging for cobalt were the same—“Muango yangu njoo soko.” My body is my marketplace.

The fact that families across the DRC are faced with the non-choice of putting a child in school or putting them to work so that the family can survive means that those families have been abandoned by the Congolese state just as much as they have been abandoned by the global economy.

I asked the officials if they could explain why schools in the Congo were inadequately funded even though education up to eighteen years of age was supposed to be free. They did not have an answer. No one anywhere did.

Everyone who digs in Kasulo lives in mortal fear of being buried alive. It is a neighborhood of concentrated hazard and the distillation of the entire system of cobalt mining in the Congo—all the madness, violence, and indignity culminate here. Kasulo is also the face of everything that is wrong with the global economy. Nothing matters here but the resource; people and environment are disposable.