More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

December 8 - December 18, 2023

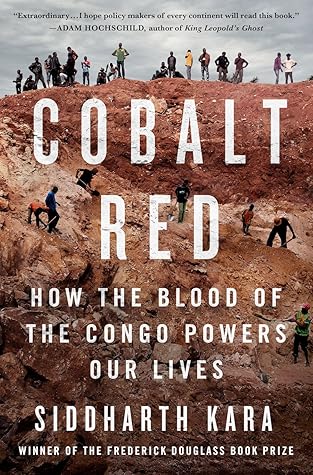

Until this moment, I thought that the ground in the Congo took its vermillion hue from the copper in the dirt, but now I cannot help but wonder whether the earth here is red because of all the blood that has spilled upon it.

I can see his face now, locked in a terminal expression of dread. That is the lasting image I take from the Congo—the heart of Africa reduced to the bloodstained corpse of a child, who died solely because he was digging for cobalt.

Our daily lives are powered by a human and environmental catastrophe in the Congo.

Today, these laborers are assigned the quaint term artisanal miners, and they toil in a shadowy substrate of the global mining industry called artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM).

In short order, Belgium, the United Nations, the United States, and the neocolonial interests they represented rejected Lumumba’s vision, conspired to assassinate him, and propped up a violent dictator, Joseph Mobutu, in his place.

The scale of destruction is enormous, and the magnitude of suffering is incalculable.

At no point in their history have the Congolese people benefited in any meaningful way from the monetization of their country’s resources. Rather, they have often served as a slave labor force for the extraction of those resources at minimum cost and maximum suffering.

As of 2022, there is no such thing as a clean supply chain of cobalt from the Congo. All cobalt sourced from the DRC is tainted by various degrees of abuse, including slavery, child labor, forced labor, debt bondage, human trafficking, hazardous and toxic working conditions, pathetic wages, injury and death, and incalculable environmental harm.

For the foreseeable future, there will be no avoiding cobalt from the Congo, which means there will be no avoiding the devastation that cobalt mining causes the people and environment of the mining provinces of the DRC.

Cobalt mining is the slave farm perfected—the cost of labor has been nullified through the degradation of Africans at the bottom of an economic chain that purports to exonerate all participants of accountability through a shrewd scheme of obfuscation adorned with hypocritical proclamations about the preservation of human rights.

Stairs sent his two most trusted men to reason with Msiri, but after three days of failed negotiations, the Europeans shot Msiri, decapitated him, and stuck his head on a pole for all to see the consequences of standing against Leopold and his Congo Free State.

If the mining sector makes itself known upon arrival at the Lubumbashi airport, so too does the police state.

No one knows how many people live in Lubumbashi—or in any other Congolese city, for that matter—because the last census conducted by the government was in 1984.

Displacement of the native population due to mine expansion is a major crisis in the mining provinces. As the living conditions of displaced people worsen, their desperation increases, and that desperation is precisely what

drives thousands of local inhabitants to scrounge for cobalt in hazardous conditions on the land they once occupied. Makaza said he lived in constant fear of being displaced the next time the mine expanded, or when some new mine was built.

“In Congo, the government is weak. Our state institutions are impotent. They are kept this way so they can be manipulated by the president to suit his ambitions,” Reine said. “Congo is only a bank account for the president,” Gloria added.

Let me tell you the most important thing that no one is discussing. The mineral reserves in Congo will last another forty years, maybe fifty? During that time, the population of Congo will double. If our resources are sold to foreigners for the benefit of the political elite, instead of investing in education and development for our people, in two generations, we will have two hundred million people who are poor, uneducated, and have nothing left of value. This is what is happening, and if it does not stop, it will be a disaster.

From pit, to pool, to sack of stones—the family had subdivided the steps involved in getting cobalt out of the ground and packed for transport by négociants. The négociants then sold the cobalt into the formal supply chain via nondescript depots along the highway. Laundering minerals from child to battery was just that simple.

It seemed as if half the teenage girls at the site had infants strapped to their backs. Boys as young as six took wide stances and summoned all the strength in their bony arms to hack at the earth with rusted spades. Other children teetered under the weight of stuffed raffia sacks they dragged from pits to pools.

Sexual assault by male artisanal miners, négociants, and soldiers was common in mining areas. The women said they all knew someone who had been shoved into a pit and attacked, the likely cause of at least some of the babies strapped to teenage backs.

Priscille said that she had no family and lived in a small hut on her own. Her husband used to work at this site with her, but he died a year ago from a respiratory illness. They tried to have children, but she miscarried twice. “I thank God for taking my babies,” she said. “Here it is better not to be born.”

I wandered back into the mining area to take a final look before darkness fell. The devastated landscape resembled a battlefield after an aerial bombardment.

Beyond the horizon, beyond all reason and morality, people from another world awoke and checked their smartphones. None of the artisanal miners I met in Kipushi had ever even seen one.

There was nothing to stop mining companies from going to the artisanal sites themselves and directly paying the women, men, and children who dug their cobalt—aside from the negative optics associated with having direct links to hazardous, penny-wage artisanal mining areas teeming with children.

In the studies we conducted, the artisanal miners have more than forty times the amount of cobalt in their urine as the control groups. They also have five times the level of lead and four times the level of uranium. Even the inhabitants living close to the mining areas who do not work as artisanal miners have very high concentrations of trace metals in their systems, including cobalt, copper, zinc, lead, cadmium, germanium, nickel, vanadium, chromium, and uranium.

The mining companies do not control the runoff of effluents from their processing operations. They do not clean up when they have chemical spills. Toxic dust and gases from mining plants and diesel equipment spreads for many kilometers and are inhaled by the local population. The mining companies have polluted the entire region. All the crops, animals, and fish stocks are contaminated.

“The funding was initiated by German car companies to help clean their cobalt supply chains,” Alex said. The IDAK team shared a copy of a comprehensive guide they published in 2014 that outlined their recommendations on corporate social responsibility in the Congolese mining sector. “This guide includes a plan for the removal of children from artisanal mining,” Mbuya explained. In addition to focusing on child labor, IDAK’s CSR plan described programs for strengthening local communities, building and staffing schools, promoting alternate livelihoods, and improving public health capacity and

...more

Therein lies the great tragedy of the Congo’s mining provinces—no one up the chain considers themselves responsible for the artisanal miners, even though they all profit from them.

My meeting with IDAK revealed that there were tangible efforts at the local level to address abuses in the artisanal mining sector, even if those efforts did not seem to be translating into meaningful progress on the ground.

They tell the international community about their programs in Congo and how the cobalt is clean, and this allows their constituents to say everything is okay. Actually, this makes the situation worse because the companies will say—“GBA assures us the situation is good. RMI says the cobalt is clean.” Because of this, no one tries to improve the conditions.

By the time one tallied such a list, how much cobalt would be left in the world that was untouched by catastrophe in the Congo?

The white man is very clever. He came quietly and peaceably with his religion. We were amused at his foolishness and allowed him to stay … He has put a knife on the things that held us together and we have fallen apart. —Chinua Achebe, Things Fall Apart

NOTHING LOOKS THE SAME after a trip to the Congo. The world back home no longer makes sense. It is difficult to reconcile how it even inhabits the same planet. Neatly arranged mountains of vegetables at grocery stores seem vulgar. Bright lights and flushing toilets seem like sorcery. Clean air and water feel like a crime. The markers of wealth and consumption appear violent. Most of it was built, after all, on violence, neatly tucked away in history books that tend to sanitize the truth.

Imagine for a moment the toll taken on a person, a family, a people, a continent across centuries of the slave trade, followed by a century of colonization. Empires were built and generations of wealth were amassed across the Western world in this manner. Perhaps that is the most enduring contrast of all between our world and theirs—our generally safe and satisfied nations can scarcely function without forcing great violence upon the people of Africa. The catastrophe in the mining provinces of the Congo is the latest chapter in this unholy tale.

She said that when she first left Likasi in the mid-1980s, there was no artisanal mining taking place. The original Belgian copper mines were run by Gécamines, and most of the men who lived in Likasi and Kambove worked at them. After Gécamines closed the mines, people started digging for themselves. “At that time, what they earned from the copper was enough,” Solange said. “We did not have to send our children to dig.”

Solange said that everything changed in 2012. “[Joseph] Kabila sold the mines to the Chinese. They made it seem like a blessing. They said we should dig cobalt and get rich. Everyone started to dig, but no one became rich. We do not earn enough to meet our needs.”

“Look at my grandchildren. This is what cobalt has done to Congolese children. They have no more future.”

The more villages I visited in the Congo, the more I appreciated how challenging it was for a child to go to school.

Josephine said that most families in poor villages around Likasi were not able to pay the school fees on a consistent basis and that as a consequence, parents often sent their children to work instead. Digging for cobalt was the surest way to walk home each day with at least some money.

It was no wonder that impoverished families across the Congo’s mining provinces relied on child labor to survive. At times, it felt like cobalt stakeholders up the chain counted on it. Why help build schools or fund proper education for Congolese children living in mining communities, when the children could just dig up cobalt for pennies instead?

The eldest, Peter, wore blue jeans, plastic slippers, and a red shirt with the letters AIG stitched on the front. Imagine that on a remote hill deep in the Congo’s mining provinces, a child can be found digging for cobalt, wearing a muddy shirt with the logo of the behemoth American financial services company that had to be bailed out for $180 billion during the 2008 financial crisis. Imagine what even 1 percent of that money could do in a place like this, if it were spent on the people who needed it, not stolen by those who exploited them.

her expression changed to that of a terrified child. Our eyes locked in recognition. I think we both understood that she was doomed.

These types of bureaucratic delays were endemic to the DRC. To this day, the official national identification cards used by every citizen in the DRC to prove their citizenship have not been updated since 1997, when the country was called Zaire. As a result, most people use their voter registration cards as a substitute form of identification. Why are the Congolese people still using their Zaire national ID cards from 1997? Because new national ID cards require that the government conduct a new national census, and the last one was conducted in 1984.

I was surprised that a SAEMAPE official admitted to the existence of child labor at a formal mining site, especially since most government employees that I met took great pains to deny or diminish the existence of child labor in artisanal mining. One senior parliamentarian in Kinshasa once told me that the international community was mistaken about the issue of child labor at artisanal mines in the Congo. According to him, they were actually Pygmies.

I inquired the next day if it might be possible to try again to see Kimpese or perhaps some other artisanal site in the mountains, but permission was not forthcoming. I never managed to return to the remote wilderness near the Zambian border, nor in any depth to the hills around Likasi and Kambove,

but I saw enough to conclude that there was a secret world of artisanal mining hidden in these hills that operated in an even more oppressive manner than the more visible sites like Kipushi and Tocotens.

I asked Arthur if he thought the army had forcibly relocated the villagers to the settlement to dig for cobalt. “No one wants to live out there! But there is cobalt and gold, so the army takes the poorest people and makes them dig.”

“What did that child die for?” he asked. “For one sack of cobalt? Is that what Congolese children are worth?”