More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

July 28 - August 4, 2024

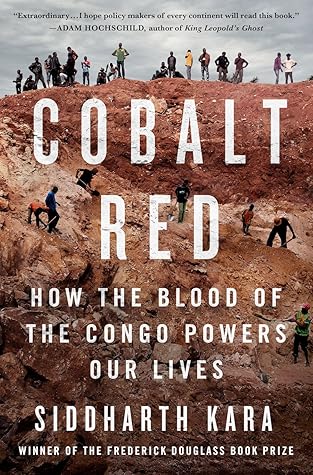

Until this moment, I thought that the ground in the Congo took its vermillion hue from the copper in the dirt, but now I cannot help but wonder whether the earth here is red because of all the blood that has spilled upon it.

Villages cling to the roadside like fingertips at a cliff’s edge.

Thousands of tons of cobalt were being fed from this shadow economy into the formal supply chain by a ragged population in conditions that at times were next of kin to slavery.

Arthur took a long sip of his beer and stared morosely. “What did that child die for?” he asked. “For one sack of cobalt? Is that what Congolese children are worth?”

Such assertions are as meaningless as trying to claim that one can discriminate the water from different tributaries while standing at the mouth of the Congo River.

Look up Kolwezi on Google Earth and zoom in. See the colossal craters, the behemoth open-pit mines, and the immense swaths of dirt. Small artificial lakes provide water to the mining operations, not to the city’s inhabitants. Villages have been flattened. Forests have been razed. The earth has been gouged and gashed. Mines swallow all.

There is more misery-for-profit in Kolwezi than perhaps any other city in the world.

The global economy presses like a dead weight on the artisanal miners, crushing them into the very earth upon which they scrounge.

“Kasulo is a cemetery,” Claude told me with the eyes of a priest who has lost faith in God. “No one knows how many people are buried here.”